vol. 13 no. 4, December 2008

vol. 13 no. 4, December 2008 | ||||

Information use is regarded as an extremely difficult area of study. The reason for this is the focus on human information behaviour including cognitive and physical processing of information. Difficulties appear in attempts to determine the subject, derive categories, and realize empirical studies. More empirical research is required (Kari 2007). This is true especially with respect to research on relevance as a complex notion, as stated in recent reviews by Saracevic (2007a; 2007b).

The naturalistic paradigm is convenient for studies of human information behaviour because it applies qualitative methods to understanding information use in contexts. In this paper relevance studies are used as a framework for the interpretation of relationships between relevance and information use. We report on findings of a study of doctoral students regarding relevance judgments. PhD students were selected because they are a special group that integrates both education and research in academic information use. The literature on relevance, including experiments, surveys and observations is extensive (Saracevic 2007b) and outside the scope of this paper. However, our interest is in human relevance behaviour which could help understand the complexity of relevance beyond traditional views.

In this research we shall try to discover new aspects of relevance. It was inspired by phenomenology (Wilson 2000b) based on the assumption that relevance is a specific experience in information use. Of course, we stress the users' view on relevance behaviour, following the huge amount of work on relevance (Saracevic 2007a). We agree that relevance is created and derived, dynamically sought for, constructed and situationally conditioned. The specific methodological background for design and interpretation of the case study was phenomenography (Limberg 1999; Phenomenography Crossroads). Phenomenography seeks to explain different ways of experiencing the phenomenon of relevance. In our case we tried to discover how relevance relates to information use for PhD. students.

We suggest hypotheses for applying the results of our study to new models of information use in the academic information environment. Resulting patterns of relevance judgments can be used by developers of systems or librarians for design of value-added services. Knowledge of behaviour patterns can be applied to information literacy and to models of information use in the academic electronic environment. For the next generations of information environments, such as digital libraries or Web 2.0 services, deeper knowledge of cognitive and interactive aspects of relevance will be necessary.

The paper is organised as follows. The following section presents related work as a background to the study. Further sections concentrate on a case study, based on our own research on relevance, including goals, methods and results. As a result a conceptual model of collective discourse on relevance is derived. Results are further explained and visualized in concept maps. In conclusion, implications for academic librarianship, information professionals and policy makers are proposed.

In a comprehensive review of progress in research of relevance in information science Saracevic (2007a) summarized advances and contemporary thinking on the topic. He states that thirst for relevant information becomes global and that still many 'fascinating questions worthy of research could be asked' (Saracevic 2007b: 2140). In accordance with this we developed research oriented towards human relevance behaviour in information use. According to Bates, information use and relevance are implicitly included in several information behaviour theories, either based on cognitive, constructivist approaches (Kuhltau, Dervin), socio-cognitive approaches (Hjørland, Paisley), or ethnographic approaches (Chatman, Fisher) (Bates 2005b).

Information use and implicit relevance can be found in Dervin's methodology of sense-making (outcomes, contexts) (Dervin 2005) and in Wilson's models of information behaviour (feedback of information processing and use) (Wilson 2005). Information use is part of information seeking behaviour determined as physical and cognitive activities working in the inclusion of the found information into the existing knowledge base of humans (Wilson 2000a). Based on analyses of peer-reviewed papers in library and information science Kari (2007) conceptualizes information use in terms of the outcomes of information. Two categories of outcomes represent the use: the active outcomes (internalization of information, conscious use), and the effects, passive outcomes (effects of information in the activity).

Information use in organizations is explained by Choo (2007) as a dynamic, interactive social process of inquiry that may result in construction of meaning or making decisions. The study by Bartlett and Toms (2005) further identified categories of input, interpretation and direction as guided decision-making in information use.

From the users' point-of-view the concept of relevance can be interpreted as seeking meaning and making sense through links between people and information. Some of the links become borders that determine what will, and what will not, be incorporated into the cognitive structure. That is why we believe that phenomenological inquiry into the experience of users when judging relevance can be fruitful for disclosing the complexity of relevance. Relevance can be considered as an inference and a relationship. The concept of situational relevance and multidimensionality of relevance based on development of information need was clearly explained by Borlund (2003). The cognitive viewpoint on relevance is similarly reflected in our study towards the determination of criteria, types, levels, and components of relevance.

Another inspiration was the framework of information seeking and retrieval in contexts (Ingwersen and Järvelin 2005). Similar models synthesize information seeking (e.g., Ellis 2005; Kuhltau 2005a) with information retrieval. In line with several studies of relevance (Froehlich 1994; Saracevic 1996; 2007a; 2007b; Mizzaro 1997) we are interested in understanding the phenomenon of relevance manifested by natural human information behaviour. The naturalistic approach in information behaviour research is represented especially by Dervin's sense-making methodology (Dervin 2003). Complementary aspects for design of our study were socio-cognitive relevance (Hjørland 2002), the user-centred relevance (Bruce 1994) and discourse analysis (Talja 2005). New concepts of relevance emphasize relevance in action. In the study by Anderson (2006) relevance is interpreted as an experience, and by connections and communication that integrates sense-making methodology and relevance studies.

Another concern arises when we think about relevance and information use in the electronic environment. Marchionini (1997) found that information extraction is based on conceptual processing, especially reading, classifying and storing information. Bates's berrypicking model (Bates 2005c) contributes to new views on relevance in the Web environment. Changes of knowledge states and different strategies of information seeking become driving forces of relevance judgments. The networked information environment may trigger new patterns of relevance assessments based on personal information management and collaboration. We suppose that in the networked environment, more value can be added by conversation, sharing, categorization and visualization. Although the users' viewpoint relates relevance to information need, it can be assumed that non-linear and exploratory features of information seeking are mapped into relevance judgments. We also suppose that interactive interconnections, collaborative uses and image clues influence relevance judgments.

Relevance judgments operate on multiple criteria including decision frameworks, situations and contexts. This has been confirmed by concepts of situational relevance (Borlund 2003), psychological relevance (Harter 1992), or graded relevance (Maglaughlin and Sonnenwald 2002; Spink et al. 1998). Barry and Schamber (1998) provided empirical evidence that a finite range of criteria for relevance judgments and use of information exists. Borlund (2003) proved multidimensionality and dynamics of relevance including classes and types of relevance (relevancies), relevance criteria, degrees of relevance and levels of relevance. Borlund, Saracevic and many other authors call for more empirical evidence to support relevance research which could help disclose implicit attributes of relevance.

Our study was aimed at discovering perceptions of relevance and deriving proposals for more effective ways of information use. To cover the complexity of relevance we draw on related studies (Anderson 2005; Borlund 2003; Barry and Schamber 1998) and phenomenography (Limberg 2000). Based on this, a framework research was designed to examine PhD students' relevance behaviour. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty-one PhD students and Masters' graduates at the Faculty of Philosophy, Comenius University Bratislava, Slovakia. Participants were selected from various disciplines in the social sciences, the majority of them having a library and information science degree.

The interviews were conducted by two researchers over five months (October 2005-February 2006). The interviews lasted between 25 to 60 minutes. Subjects were between 24 and 47 years of age; the average age was 28. 9 years. Sex distribution was 12 women (57 %) and 9 men (43%). Students' majors were diverse, 13 subjects came from library and information science (61%) and eight from other disciplines (39%) (philosophy, ethnology, journalism, psychology and history).

The following questions directed the framework of the study:

The semi-structured interviews consisted of fourteen open-ended questions. Questions concentrated on the rise of the information need and previous experiences with professional information. In the first part, participants were asked to explain their idea of relevance. After this, we asked them to recall activities, decisions and criteria which they had to apply to relevance judgments. We then examined differences in relevance judgments in the electronic and printed environments. Further questions concerned auxiliary sorting of information, influences, supportive intuitive clues and relationships between subjective and objective components. We also asked them to identify differences between the orientation stage and the problem-solving stage. The affective component of information behaviour was represented by questions about emotions and the most interesting part of relevance judgments. The interaction between cognitive and affective components was integrated by a question on metaphor or simile.

A number of supportive methodological materials were used within the study. We also conducted a focus group discussion. Methodological materials including interview questions were published in the final research report (Steinerová et al. 2007) and elsewhere (Steinerová 2007).

The interviews and discussions were recorded and transcribed. Three researchers analysed and interpreted the study data in several steps. In the first step, the answers were analysed, coded and integrated. For quantitative analyses concept frequencies and occurrences were summarized in tables. Resulting conceptual structures were further categorised. The validity and reliability of results are provided by three independent analyses and interpretations. Selected participants evaluated results. Finally, interpretations and concept maps of collective discourse emerged.

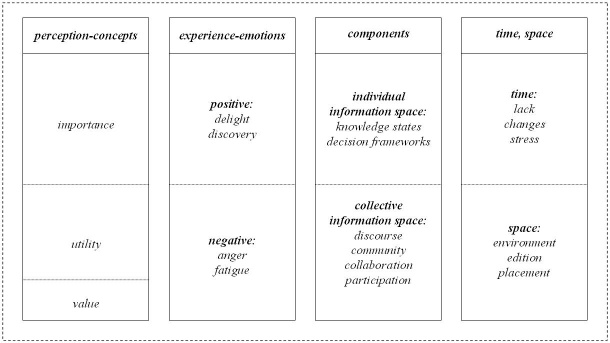

Following the research questions we derived a resulting synthesized model of collective discourse of participants (Figure 1). This model is composed of the four following parts: perception of relevance; experienced emotions; individual and collective components of relevance; and time and space framework. The columns of the model in Figure 1 visualize these parts.

Figure 1 illustrates final synthesis of relevance perceptions of participants. Importance, utility and value are depicted in the first column according to frequency of single terms. The next column divides emotions into positive and negative with the most frequent expressions of participants. The third column derived the main components of individual and collective information spaces. The last column describes time and space aspects of relevance as mentioned by students. Single parts of the model are explained in more detail in next sections.

The meaning of relevance emerged from the collective discourse of participants and was categorized into the three categories: value, utility and importance of information. Value of information represents its internal integrity, validity and reliability. Participants related this meaning to a process, a number of them emphasized verification, authentication and credibility of information. Trustworthiness of the source and verity of information were also regarded as significant. Utility narrows the extension of value towards a more concrete use of information. Utility is embedded in the contexts of information use, namely in relation to topic, problem solving and time. Importance expresses qualities of relevance such as emphasis on the problem essence, priorities and the hierarchical division of information (important or peripheral). Participants emphasised what they termed, 'focal, carrying information' (meaning the core information, the information that carries meaning and helps the person to find focus), implicit categorisation and the subjective nature of relevance. It is connected with taking up a position and an ability to select. The analysis showed that the most frequent metaphors expressed the idea of relevance as linking (putting through, fitting in). They also mentioned that information structures mirror people. For example, 'seeking oneself', 'mirror', 'connection of myself with something else', 'wheel work' and 'puzzle'.

We categorized participants' feelings by using basic approaches to human emotions and applied the following dimensions:

Content analysis showed that, at the level of agreeable feelings, the most often used expression was delight. This refers to a pleasant feeling of achieving something desired. Different grades of intensity of delight were manifested by concepts of satisfaction and happiness. Negative feelings have been verbalized by higher grade of activation, namely anger as reactions to obstacles while achieving a goal. Contexts of anger have been explained from different perspectives; for example, anger at oneself ('that I was not able to better articulate the requirement'), or anger as rage ('when information is based on false points'). Other negative feelings were grouped around the concept of fear, including uncertainty, helplessness and anxiety.

Participants emphasised that they enjoyed creative thinking, finding something of value and discovering something new. Some of them appreciated the experience of understanding the problem, inspiration and learning. The agreeable part of relevance judgment was perceived as a positive value that can be achieved by quality information. Participants also appreciated selection of something interesting, moments of surprise and understanding which led to successful problem solving.

The basic criteria used for assessing relevance from professional texts were grouped into the categories: author, topic, activities and contexts. Participants also confirmed that they created and used these criteria intuitively. This finding corresponds with similar studies that proved the existence of informal criteria (Schamber et al. 1990; Barry and Schamber 1998; Borlund 2003). The intuitive, informal and incremental character of the process of relevance judgment emerged from the analysis. The intuitive criteria were divided into people's subjective states and objective intuitive clues. Subjective states included categories such as mood, reconstruction of information, inference, cognitive prediction and 'first information', for example, the impact of the first, two or three Web pages retrieved by the search engine. Other clues revealed serendipity and unique personal experience. Subjective emotions may have both positive and negative effects, namely lack of time. Participants confirmed that their relevance judgments depend on their basic mood, their attitudes to information, but also on a sense of context. Preliminary outlines or schemes of information structuring make the interaction between a person and information easier.

Objective intuitive indicators were determined as document content, document form and authors. In the category of document content, participants mentioned such clues as ways of formulation and the authors' organisation and interpretation of texts. Visual and linguistic clues, namely graphics, simple language and style were confirmed as exceptionally important. The criterion of the author was connected with implicit trustworthiness and integrity of information. They also mentioned such indicators as opinions of certain persons (experts, consultants), one's own experience and knowledge, or empirical data and facts.

The individual information space was determined. It covers knowledge states, emotions and decision frameworks used in relevance judgements. The collective information space is based on discourse and community. It is manifested in collaboration and participation in groups. The interaction of these spaces is strengthened in the electronic environment, facilitated by personalization towards knowledge states and mood and by participation and collaboration in social networks.

Our subjects confirmed that basic time dimension in information is manifested by lack of time, time pressure and information overload. It was admitted that relevance changes by knowledge evolution in time, as found by Vakkari and Hakala (2000) and confirmed by others, especially dynamics and multidimensionality of relevance emphasized by Borlund (2003). The time framework of relevance judgment is enriched by the possibilities of asynchronous or synchronous electronic communication.

The space framework was categorized as the place (or Website) of the information source and the data about the origin and owner of the source (author, creator or publisher). These clues were confirmed as important for judging the reliability and verity of information. Our resulting model confirmed a common set of criteria across different users. Differences are due to situational contexts and personal experience. We tried to look beyond topical, binary and stable interpretations of relevance. We also applied concept mapping for modelling the collective discourse of participants. The concept mapping is explained in the next section.

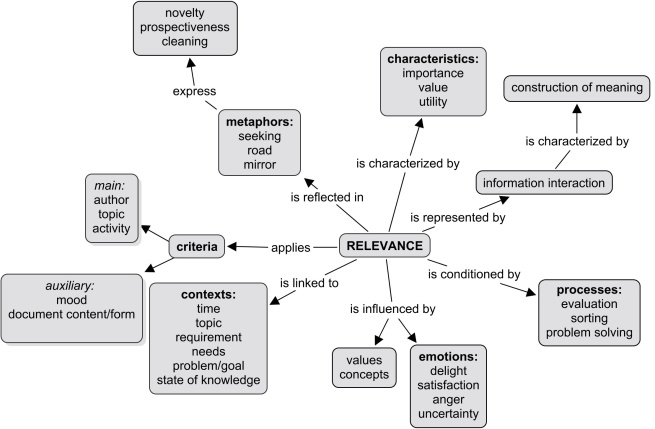

Higher level synthesis and modelling resulted in four concept maps corresponding to the four research questions. The maps represent categories of the participants' collective discourse. The mapping was visualized with the use of C-maps tool (Novak and Canas 2008) and the four maps consist of:

The concept map Perception of relevance depicts basic characteristics of relevance, the most important processes and metaphoric images. The map summarizes the used criteria, contexts and the impact of emotions. The map visualized the analysed data concerning the meaning of relevance, metaphors, activities, criteria for relevance assessment, emotions and interesting parts of the process. Semantic links in the map indicate characteristics, conditions, use of criteria and influences of human interaction with information. The main characteristics of relevance emerged as importance, value and utility. Metaphoric images of relevance as seeking and moving on a road express a quest for novelty, predictions and clarification of meaning by relevance judgments. Relevance is conditioned by processes of evaluating, sorting and problem solving. Relevance is influenced by emotions and values. Relevance is linked with such contexts as time, topic, requirement, need, problem or goal and knowledge state. The criteria for assessment are divided into the main criteria of author, topic and activity and the auxiliary criteria as mood, content and form of the document.

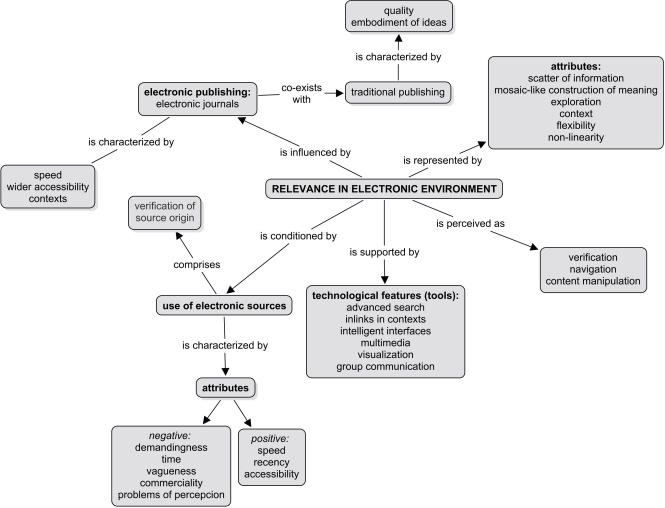

The concept map on Relevance in the electronic environment (Figure 3) determines differences that emerged from the use of electronic resources and electronic publishing. The main activities of verification, navigation and content manipulations are described. The process of relevance assessment is supported by technological features. The map synthesized answers to questions about differences between traditional and electronic resources. The quest for the origin of a source is facilitated by such characteristics as scattered information, serendipity of information discovery, context, flexibility and non-linearity.

Relevance judgments are enhanced by the advanced technological features of interfaces and search engines. Students confirmed that they used electronic sources frequently, but that use is conditioned by contexts: topics, disciplines and tasks. In the electronic environment they appreciated topicality, speed and technological features such as findability, multimedia and linking. They preferred printed sources because of their quality, intellectual depth, stability and predictability. Printed sources were approached in a more emotional way, putting stress on readability and reliability. Several students expressed differences between the perception of printed and electronic texts. They agreed that manifold mediation in electronic texts make the construction of meanings more complicated.

The emerging model of relevance in the networked environment could be built on rich and efficient electronic information processing, which integrates creation, seeking and use. Relevance in this environment is marked by non-linearity, flexibility of navigation, high-level visualization and collective information processing. The map confirmed the determination of relevance not only by user needs but also by technological development.

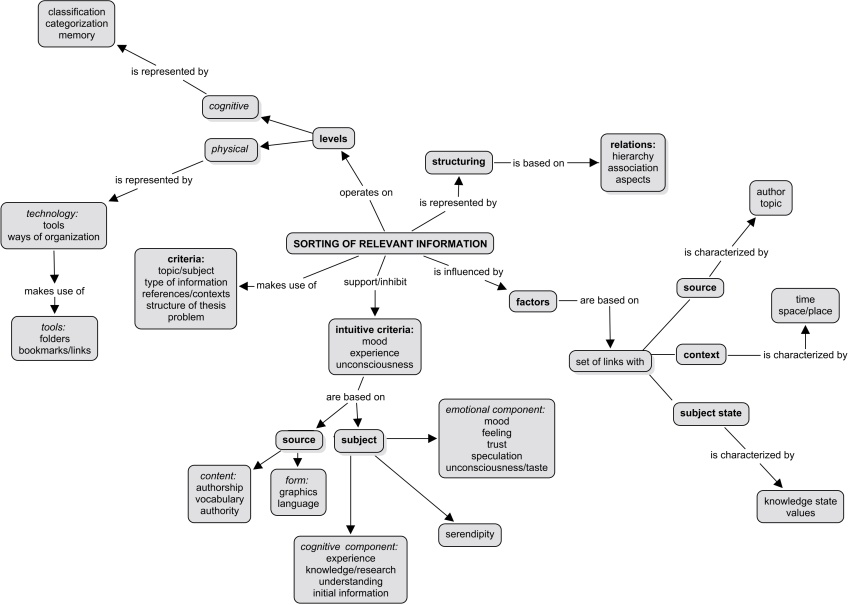

The concept map on Sorting of relevant information (Figure 4) visualized principles of structuring relevant information at the cognitive and the physical levels. The map depicts the criteria and factors that influence sorting, based on sources and subjects. It synthesizes the data based on questions about auxiliary sorting of information and intuitive clues. The main principles of information structuring are based on such relationships as hierarchy, associations and aspects. The sorting applies such criteria as topic or subject, type of information, references, conceptual structure and problem.

The goals of relevant information structuring are to create contexts and reduce cognitive load. It is led by categorization based on clustering and by classification using hierarchy and linearity. Following the analyses an important part is played by memory. Students confirmed that they combined broader principles of ordering (e.g., faceted organization) with more detailed sorting (e.g., the detailed outline of a thesis).

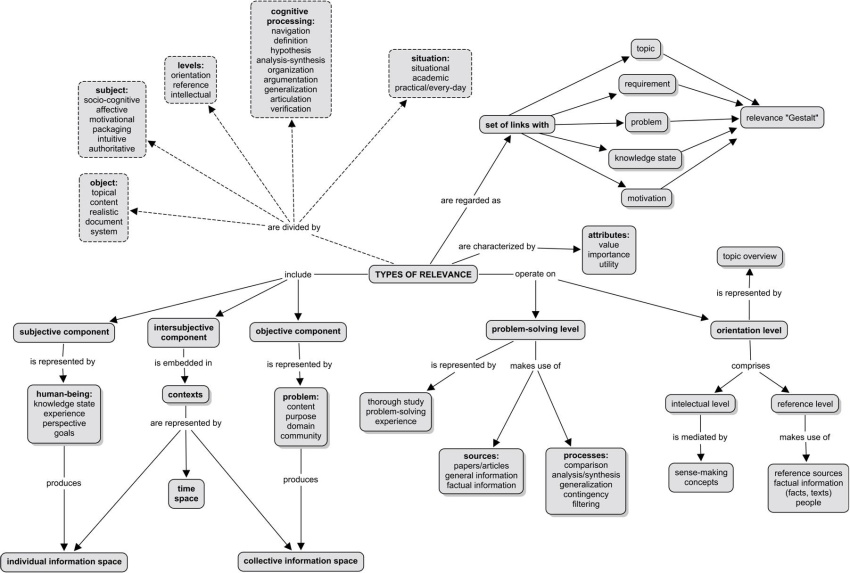

The concept map, Types of relevance (Figure 5) represents the access to information at the levels of orientation (introduction to a topic) and problem solving (study). The map indicates mutual relationships of the subjective and objective components in contexts. Relevance is determined as different kinds of links that create topical patterns. The types of relevance are derived by criteria of the object, subject, level of problem solving, cognitive processing and situation. The map synthesizes answers to questions about the information used in the stages of orientation and problem solving, the subjective and objective characteristics of relevance, components and types of relevant information. For example, the criterion of cognitive processing resulted in the following relevance types: navigational, definitional, hypothetical, analytic and synthetic relevancies, relevancies based on organization, argumentation, generalization, verification and articulation.

Our study confirmed multidimensional complexity of relevance and information use, as explained by Borlund (2003) and Saracevic (2007a). The non-usual method of phenomenography and resulting concept maps can be regarded as adding value beyond traditional relevance research. Relevance behaviour results show possibilities and challenges for further research.

It was confirmed that relevance is perceived as something of value, utility and importance and the quality of resources plays an important role. Utility confirms pragmatic contexts of information use which is conceptualized by outcomes of information seeking (Kari 2007). Importance emerges especially from interpretative repertoires investigated by social constructionism (McKenzie 2005; Tuominen et al. 2005). The vital role of emotions help users integrate relevance judgments. We have identified positive feelings of delight and enthusiasm, negative feelings included especially anger. The phenomenographic approach proved useful in discovering variations of experiencing relevance in derived categories.

Our study results point to multiple discovery experiences in relevance judgments. We suppose that instead of locating information it is more beneficial to provide users with features of ranking, relating, recommending and support of other intellectual activities. Findings suggest that relevance judgment is both multi-criteria cognitive processing and decision-making based on constructing meanings out of contexts. Interactions cause successive emergence of sense in social, organizational and cultural contexts.

Our study participants confirmed that relevance judgments are based on activities of evaluation, problem solving, decision-making and organization of information. Explicit components of relevance are represented by concepts manifested by communication and behaviour. Implicit components comprise values, contexts and principles of information structuring. Relevance emerges from experience, personal preferences and social collaboration which can be supported by technological features. Relevance judgments in digital networked environment can form special patterns. As disaggregation of digital content to smaller units of use proceeds, the desire for context increases. Thus, in the networked environment relevance moves closer to information need, as it is possible to build a persons's own mosaics made of pieces of information. Again, this finding corresponds with Borlund's model (2003) relating relevance to information need.

Our findings support the argument about stratified and dynamic contexts of dissertation research which include topic, problem types and accessibility (Vakkari and Pennanen 2001). This is in common with other, similar studies, e.g., (Barry 1994; Byström 2000; Choo 2007; Saracevic 2007b), when context emerges as the main driving force of information use. In comparison to these and other large scale studies, our study is different in using the phenomenographic method with a focus on the experience of relevance by doctoral students. The findings suggest that relevance as perception, cognition and experience is linked with creative thought. Relevance as experience is integrated by emotions and relevance as interaction is based on communication. The central finding is that the same criteria are used across various types of sources (traditional, electronic) and contexts.

The resulting concept maps indicate that users need support for discovering, decision-making and participation as part of relevance assessment. It is helpful if human cognitive and affective processes are complemented by technological features. The natural relevance behaviour of users is manifested by spontaneous and informal revelation of focus. Information systems tools could help support criteria with clues for access to previous experience. Features that enhance delight and discovery could be beneficial.

It would be interesting to further investigate supportive values and contexts, which help to determine and trigger an appropriate decision-making framework. Relevance behaviour could be further studied in terms of finding information ecology as sense-making interactions between human actors and the academic information environment.

We can also derive several implications for academic and research libraries. For this purpose we put the results of our study into contexts of other studies of user behaviour patterns, e.g., OCLC reports, or CIBER reports (OCLC 2007, Rowlands et al. 2008). Library and information services are not only transformed into the electronic environment. It becomes vital that services and systems can apply knowledge of human relevance behaviour. It would be helpful if national, academic and research libraries could establish special departments focused on research of user behaviour related to relevance assessment in information use.

Information professionals should pay more attention to relevance assessment. Relevance assessment might become part of information and media literacy programmes. With regard to information literacy relevance judgment proceeds from orientation to analysis. Relevance assessment integrates sensory-motor, cognitive, affective, communicative and social activities and skills. Our study showed that relevance can be further studied as experience, interaction and creative thinking.

Our concept maps can be used for learning at different levels of information literacy development. The maps can help visualize knowledge representations in digital libraries for education and research. Policy makers should consider relevance behaviour in information strategies at institutional or national levels. Deeper research into relevance behaviour can help develop new rules of information processing and use in the networked social library of the future.

The author gratefully acknowledges cooperation and efforts of all participants and co-workers of the research project VEGA 1/2481/05, especially Mirka Grešková. I would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments on the draft of this paper. The paper is based on the results of the research project VEGA 1/2481/05.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the author, 2008. Last updated 10 December, 2008 |