Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19-22 August, 2013

An integrated model of information literacy, based upon domain learning

Gary B. Thompson and Jonathan W. Lathey

Siena College, Standish Library, 515 Loudon Rd, Loudonville , NY 12211, USA

Introduction

While library orientations and one-shot lectures may reduce library anxiety and acquaint students with resources, they suggest that library research requires minimal instruction and minimal learning. The librarian’s task is to educate students and faculty that information literacy is not something taught in an orientation or one or two classes, but requires developmental learning with practice over a period of years to master the methods of inquiry and investigation required for the highest forms of scholarly research.

Another issue within the information literacy community regards whether library research is part of general education with skills readily transferrable to any discipline or whether library research methods must correspond with the discourse of specific disciplines. Those who think that information literacy fits best into general education focus on first year programs and introductions to library research methods. This means collaboration with introductory English instructors to teach students how to do research about an author, a literary work or other aspects of literature. An alternative is to offer a credit course which introduces students to information-gathering and gives students practice researching topics and creating bibliographies. No one would deny the value of such beginning information literacy instruction. However, this paper presents theoretical and experimental studies from cognitive learning and information science supporting the claim that domain learning and information literacy are intrinsic partners in student inquiry-based learning and investigative research. Students cannot adequately research a subject without an understanding of the related domain or discipline to assist them in information-gathering, information evaluation and synthesis. The more topical knowledge they possess, the greater their ability to do scholarly research on a subject and vice-versa; thus, the need for collaboration in teaching disciplinary subjects and information literacy.

Models of domain learning, inquiry-based learning, and information literacy development

One of the premises of this paper is that interest in and knowledge of a domain (a specific body of knowledge) is instrumental to higher-level inquiry-based learning and problem-solving. Tobias (1994: 38) evinces how domain knowledge and student interest positively affect learning, especially when the interest is enduring. Thompson and Zamboanga (2004) demonstrate that prior knowledge facilitates new learning, even if the knowledge is modest and the sources are inferior, and that growth in knowledge leads to greater critical thinking skills. Patricia Alexander’s research shows that as subject matter knowledge increases, interest in content and recall of information increases, resulting in enhanced learning (Alexander and Murphy 1997: 134-35). Christine Bruce states: 'Learning is about relations between the learner and the subject matter; the focus is not on the student or the teacher or the information, but the relation between these elements'. (Bruce et al. 2006: 6)

A related premise is that information literacy is a complex form of inquiry-based learning requiring critical thinking, problem-solving and domain knowledge. Two Cambridge University librarians, Seeker and Coonan, put forth a developmental vision of information literacy 'as a continuum that encompasses a broad range of abilities, from functional skills through high-level cognitive processes, culminating in the individual’s capacity to manage his or her own learning'. (Coonan 2011: 3) Scholars from the Netherlands Educational Technology Expertise Centre conclude: 'Just making information sources available is not sufficient to foster learning or to solve information-based problems. To succeed, learners are rather required to apply numerous cognitive skills, from searching and evaluating, to integrating information'. (Brand-Gruwel and Stadtler 2011: 178). An overarching learning objective for information literacy according to Montiel-Overall (2007: 58) is to enable learners to build on their personal knowledge through 'opportunities to use information to make connections, solve problems, and create innovative ideas that will lead to further information and knowledge'. Lupton and Bruce (2010) push librarians to go beyond generic information literacy skill-building to a more contextual perspective emphasizing personal transformation, disciplinary and professional applications, and the social impact of information and knowledge.

As information literacy became a more regular part of education, librarians investigated how students conduct library research and achieve the competencies to acquire knowledge. As a trailblazer in research into student information-gathering behaviour, Carol Kulthau recognized student anxiety towards library research and identified processes involved in selecting a topic, searching for information, and starting to write. Michael Eisenberg and R. E. Berkowitz’s 'Big6-skills model' emphasizes information problem-solving through task identification, investigation, and information evaluation and synthesis. These authors and others identified in a review article by Erdelez et al. (2011) have developed 'micro-models of information literacy and inquiry-based learning', which examine cognitive processes involved in library research and assembling research papers. These models have common elements: (1) they analyze student library research processes; (2) their unit of analysis typically is the student research project; (3) they identify student difficulties with determining the information need and selecting the topic; (4) they include the critical steps of information-gathering, evaluation, and synthesis.

Contrasted with those micro-models are macro-models of information literacy, with a more longitudinal approach to student information literacy development, with these common elements: (1) they put information literacy into a broader educational and social context; (2) the unit of analysis is the learner over a longer period of time; (3) knowledge building, knowledge management and knowledge creation receive greater emphasis. Let us turn to two important contributors to what we call the 'macro-models of information literacy and inquiry-based learning'.

Building upon studies of cognitive development, motivation, and information processing related to learning theory, Alexander created a learning model outlining stages in the acquisition of domain knowledge. She postulated that the level of domain knowledge and interest fundamentally determines the student’s success in learning strategies and the development of critical thinking for any discipline. Alexander studied how a person’s knowledge base and motivation to learn influences his ability to process information and to integrate domain knowledge. More particular for this paper, levels of disciplinary knowledge are related to students’ strategic abilities in information-gathering, information-processing and information-utilization.

Alexander’s model of domain learning provides a framework for disciplinary education by proposing three developmental stages of academic learning (Alexander 2003). The novice or acclimated learner possesses low knowledge and low interest in the academic discipline. Domain knowledge is fragmented and disjointed. The student has trouble distinguishing which information is important and she is easily distracted by 'more tangential, albeit more enticing, information' (Alexander 1997: 222). In the second stage, the competent learner achieves greater conceptual understanding, entailing a higher level of thinking and more sustained interest in the subject-matter. With a more cohesive knowledge base centered on key concepts and principles, her knowledge base serves as a scaffold for subsequent domain learning (Alexander 1997: 228). 'By using this conceptual framework, competent learners should be better able to differentiate domain-relevant and domain-irrelevant content and more important from less important information'. (Alexander 1997: 228) The more informed student is able to resist distractions and finds interest in unembellished text. In the third stage, the proficient or expert learner develops the greater interest, conceptual knowledge, cognitive skills and advanced learning strategies necessary for the highest order of critical thinking. She has the abilities and motivation to formulate problems and conduct original research in her academic discipline. 'This means that proficient or expert learners must have a role in reshaping the very landscape of the domain… by perceiving aspects of the domain in novel and insightful ways, or creating or redefining the very base of knowledge or core principles that mark a domain as unique'. (Alexander 1997: 237)

Bruce (1997) developed a parallel model of 'informed learning' focusing upon the relationship between the learner and information use. From the model of domain learning perspective, Bruce’s first four conceptions facilitate students’ knowledge acquisition: (1) experience with the technology for information-gathering; (2) knowledge of the most important domain information sources; (3) knowledge of how to do effective searching; and (4) skills at organizing information.

In the final three conceptions in Bruce’s schema, students have competence and proficiency similar to those described in Alexander’s domain learning model, and the orientation shifts to greater creativity and utilization of information. Consistent with a disciplinary model of information literacy, students are equipped with 'both knowledge about the subject-specific content and research practices of particular disciplines, as well as the broader, process-based principles of research and information retrieval that apply generally across disciplines'. (Grafstein 2002: 197) The students become competent to search strategically for information, interpret information and construct meaning from a particular perspective. The persons are transformed by information, leading to insights for creating new ideas and utilizing information in a wide range of applications (Bruce 1997).

An integrated model of domain learning and information literacy development

The authors of this paper propose a model of information literacy development emphasizing the central importance of domain knowledge and domain learning. Domain learning scholars have focused attention upon the effects of prior knowledge and student interest upon information inquiry, reading comprehension, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge organization and extension. The premise is that the learner is transformed on the road from low to high domain knowledge and interest with the ultimate goal of becoming competent and possibly an expert in a discipline.

Reference librarians encounter these stages of cognitive development as they work with students on research papers and searching. Novices (e.g. high school and first year college students) tend to exhibit low knowledge and low interest in the discipline as they are acclimating to academia in general and academic disciplines in particular. In conducting library research, they experience difficulty choosing topics and selecting terms to research the topics. They lack the knowledge bases to comprehend and critique research reports that they read or synthesize the readings in the field. Thus, they have difficulty integrating what they are reading into coherent thesis statements and sustained discussions.

Alexander’s model of domain learning states that as their domain knowledge and interest grow, learners are transformed by developing learning strategies and information-gathering strategies to enhance competence in their disciplines. Students use domain knowledge to select topics, to choose appropriate search terms, to evaluate content, and then to integrate the new knowledge with their existing bank of knowledge. Further in their academic careers, the expert learner evinces higher interest in their discipline and a broader and deeper knowledge base, enabling them to utilize a more sophisticated strategy for learning and knowledge acquisition. This leads to a new level of information literacy development, in which the student is eager to research new topics, is conversant with disciplinary concepts and methods and thus conducts comprehensive searches of the topics with maximum success. Furthermore, students take those assembled research findings, evaluate them from a deeper understanding of the topic, and not only expand their personal knowledge, but possibly extend the disciplinary knowledge on a specialized topic.

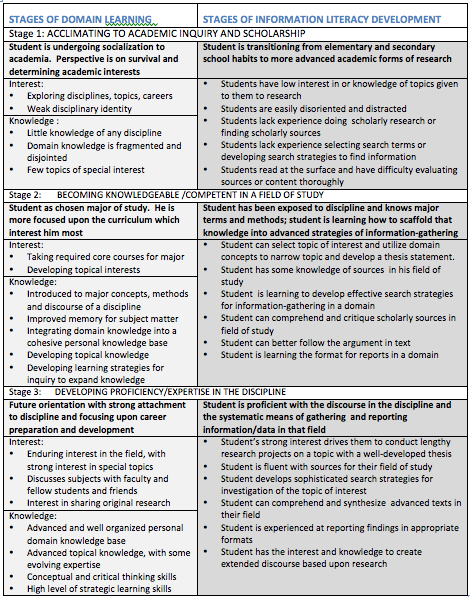

The left column in the chart below outlines characteristics of learners in the three stages of domain learning in Alexander’s model. High school and undergraduate students go through these stages of development at different rates of speed depending upon their education and experience. Novices begin with little or no knowledge of the discipline. As they progress through courses in their major, students begin to acquire disciplinary knowledge. They become competent and finally proficient with the subject matter and discourse of their chosen domain. The right column describes how the levels of domain knowledge and interest affect students’ approaches to and strategic knowledge of information literacy processes. Students start with little motivation and rather primitive information-gathering techniques. As knowledge and interest grow, students develop more targeted and tactical approaches to information gathering, leading to larger personal knowledge bases, which in turn enhance their abilities to investigate, evaluate, and integrate research findings in a synergetic relationship between domain learning and information literacy development.

Supporting literature for the link between domain learning and information literacy development

According to Alexander’s domain learning model there are two related kinds of knowledge: domain or topical knowledge and system or strategic knowledge. Information literacy is a type of strategic knowledge involving inquiry-based learning, problem-solving and critical thinking. The integrated domain learning-information literacy model states that the goal of information literacy is not only to teach students to be effective information-gatherers, but to teach students how successful information inquiries both depend upon their prior knowledge and extend their knowledge of the subject. Domain learning and information literacy development have a synergetic relationship emphasizing cognitive development and transformation. Other learning theorists and information scientists support this idea. Lazonder et al. (2008) conclude that domain knowledge enables first year students to develop higher-levels of inquiry-based learning than those without subject knowledge. Waniek and Schafer (2009) studied the interaction between domain and system knowledge, and they concluded that system knowledge produced advanced navigation skills while domain knowledge improved information processing. Diekema et al. (2011: 263) says that problem-based learning 'integrates information literacy with disciplinary content, enabling students to learn subject matter, information seeking, evaluation and synthesis skills and critical thinking skills all at the same time'. Schrader et al. (2008) provide an overview of 'The model of domain learning as a Framework for Understanding Internet Navigation'.

The interplay between domain learning and information literacy development has been studied most extensively in the arena of Internet and database searching. The studies reported come from many nations: Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Great Britain, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United States. Our literature review below focuses specifically upon differences in ability and strategy between novices and experts in executing effective Internet searching depending upon levels of domain knowledge and levels of strategic knowledge:

- Novices have difficulty getting started with framing their research topic (Diekema et al. 2011: 262; Limberg 2000: 200).

One student… knew what topic she was to write about, but didn’t know how the field viewed the topic, which questions were considered interesting and valuable by practitioners in the field. (Fister 1992: 165)

Another student said: I would have been dead in the water if I hadn’t been reading on the subject more or less…so I came with some ideas. (Fister 1992: 164)

- Novices evince disorientation, information overload, and uncertainty in conducting information searches (Desjarlais and Willoughby 2007: 6; Desjarlais et al. 2008: 255).

Novices tend to have a trial-and-error, wandering search strategy, thus taking more time to do the search (Willoughby et al. 2009: 646; Tatatabai and Shore 2005: 226, 238).

Impatience led them [novices] to navigate more, and to execute before spending enough time exploring or planning. (Tatatabai and Shore 2005: 238)

- Novices have trouble identifying effective search terms (Desjarlais et al. 2008).

- Novices are easily distracted by technology features and irrelevant information (Desjarlais et al. 2008: 258-260; Cromley and Azevedo 2009: 290).

- Novices must focus on examining the sources of information and understanding the text rather than evaluating informational content (Braten et al. 2011: 188).

- Novices have difficulty discerning relevant and important findings from the rest (Alexander et al. 1997: 224; Braten et al. 2011; Desjarlais et al. 2008: 255).

- Novices tend not to see connections between concepts and ideas and thus have trouble integrating the information discovered into a coherent discourse (Desjarlais et al. 2008).

Experts manifest higher level information literacy development than novices

- Experts have high domain knowledge and specialized knowledge of topics which help them to choose domain-related search terms and get more useful results

So, domain experts seem to be in advantage, because they can easily link prior knowledge to task requirements and to information found on the web. (Brand-Gruwell and Stadtler 2011: 176).

Thus discovery depends upon a fit between an entrepreneur’s idiosyncratic prior knowledge and a particular venture idea, which may be discovered through systematic search. (Norton and Hale 2011: 827-828).

- Experts manifest a targeted and flexible search strategy (Waniek and Schafer 2009: 235; Willoughby et al. 2009; Tatatabai and Shore 2005).

- Experts conduct searches in less time and with less navigational steps (Willoughby et al. 2009; Cromley and Azevedo 2009: 300; Park and Black 2007).

- Experts are self-regulating and adjust their search strategies based upon the information discovered and how it fits into their knowledge base (Willoughby et al. 2009: 646; Stromso and Braten 2010).

Research is cyclical, with new questions and issues emerging throughout the research process as a result of reading and learning more about a topic. (Diekema et al. 2011: 265)

Student quote: Good research means reading information critically not only for answers, but for questions and new angles. (Diekema et al. 2011: 265)

- Experts focus upon a deep processing of the content of the sources, using critical reading comprehension and well defined evaluation criteria to put findings into the context of domain knowledge (Braten et al. 2011: 189; Cromley et al. 2010;. Rouet et al. 1997; Tatatabai and Shore 2005).

Undergraduates engaged in fewer text-based strategies (e.g. rereading) and focused more on deep-processing strategies that helped them determine the main ideas of domain-related passages and build mental models of what they read. (Alexander et al. 1997: 142)

The more students become experts on the topic, the more they were able to evaluate the quality of Web information in terms of credibility of the source, as well as the accuracy and stability of its content. (Mason et al. 2011: 148)

- Experts know the discourse of the domain and how to use the information found to extend the knowledge in the field through effective reporting.

Norton identifies what an expert systematic information search strategy can do for innovation in business: “it identifies domain of competence; selects a set of information channels; crafts search strategies; develops decision criteria for signals; conducts active, constrained searches; and uses framework to evaluate the wealth-generating potential of ideas. (Norton and Hale 2011).

Differences between students’ understanding of subject content influenced how they searched for and used information. Differences in students’ experience of information seeking and use influenced both how they searched for, and used, information and what they learned about content. (Limberg 2000: 199)

Discussion and conclusion

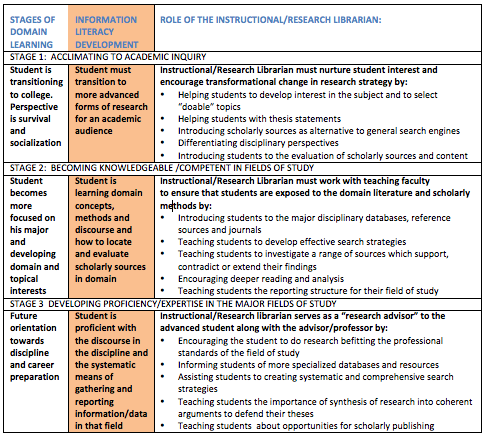

The linking of domain learning to information literacy directly impacts our approach to instruction. First, teachers and librarians must adopt a longer-term developmental approach which incorporates growth in both domain learning and information literacy. According to Alexander et al. (1997: 142): 'We did not produce (and could not produce) proficient or expert learners in the domain of educational psychology in a single semester. We did, however, contribute to their emerging competence'. Secondly, teachers and librarians must emphasize active learning which incorporates information-seeking and information-gathering activities. Domain learning and strategic learning must go hand-in hand. Effective teaching of information searching involves 'the careful coordination of knowledge, flexible use of multiple search functionalities, monitoring of progress towards these goals, and efficient use of search time'. (Cromley and Azevedo 2009: 308) Thirdly, professors and librarians must recognize their complementary roles in imparting domain knowledge and information literacy. 'It is throughout the project, as students interact with information and its sources, consult with their professor, the library faculty member, and each other that they begin to develop competence'. (Ruediger 2007: 86)

Information literacy instruction must take into account Alexander’s stages of development from acclimation through competence to expertise in a field of study. In the first stage the students strive to understand the nature of academic discourse and inquiry in general. Librarians must introduce students to the standards of academic research. Librarians also serve as mediators 'between the non-academic discourse of entering undergraduates and the specialized discourse of disciplinary faculty'. (Simmons 2005: 298). In the second stage, students undergo disciplinary socialization, during which they learn the core content, methods and discourse for their fields of study. 'Students gradually learn through reading and practicing the production of scholarly texts, the norms for what represents credible research output, what is considered good research, and what counts as a contribution to the field'. (Kautto and Talja 2007: 55) Several studies show how students’ capabilities to search for relevant sources, read and evaluate content vary depending upon the match with their disciplinary majors (Talja and Maula 2003; Park and Black 2007; Rouet et al. 1997). Librarians play a vital role in teaching students particular approaches to information-gathering, evaluation and reporting depending upon the discipline. This is especially important for topics crossing disciplines. Interdisciplinary research does not mean that it is 'non-disciplinary'; rather it means that multiple disciplines may be doing research on this topic using differing perspectives (Jones 2012). In the third stage, students assume more of the role of the topical expert whereas librarians assume the role of expert research advisors to ensure that students are highly proficient and agile at information-gathering and utilization to meet their specialized needs.

Here are some specific recommendations for teaching information literacy based upon the integrated information literacy model and the supporting literature:

- Give novice students a reading related to the domain and the topic for the research paper just prior to library instruction and practice searching; the students will be more highly motivated and navigate with a greater grasp of the topic from the point of view of that domain (Lawless et al. 2007). Otherwise, give the students an introductory guide to the subject or let them bring notes on the topic to use during the search session to improve their chances of success (Lazonder et al. 2010; Mitchell et al. 2005).

- Use concept maps, visual topical browsers and thesauri to help students with low domain knowledge to define and narrow their research topic and to decipher the relationships between search terms. This reduces disorientation and information overload and leads to improved search strategies because of an increased understanding of domain concepts (Gordon 2002; Li and Chen 2010).

- Increases the confidence of students to conduct searches by offering interactive tutorials and video clips on how to do searching, preferably related to the specific database being used. (Cromley and Azevedo 2009; Mitchell et al. 2005).

- Give students more direction in terms of which databases fit the topic and show them through examples how to proceed step-by-step with the search to prevent them from being confused or overwhelmed (Lawless et al. 2007). Thinking aloud is a good survival technique to help them develop a search strategy and perform the necessary steps. (Tatatabai and Shore 2005) This is a developmental approach to strategic information literacy to scaffold with expansion of the students’ domain or topical knowledge.

- Give novice students more time to complete their searching. (Desjarlais and Willougby 2007) If you cannot, pair a novice student with a more advanced student with higher domain knowledge. 'There is a marked difference between the performance of acclimated learners alone and with the assistance of more competent or proficient individuals". (Alexander 1997: 226)

- Librarians and faculty can collaborate to teach students techniques to get the most out of scholarly articles through deep reading and analysis of the content (MacMillan and MacKenzie 2012).

- Use more team teaching stressing the necessity for both domain learning and strategic information literacy. Ruediger (2007) gives an extended example for advertising students.

Research questions which need further exploration:

- How does this learning model work in other cultures and other educational contexts?

- How do we operationalize for students the intrinsic relationship of domain learning and information-gathering?

- How do students progress from novices to intermediate learners to experts in a field?

- How do we assess how many of our students become systematic expert searchers?

- Which types of visualizations would help students best with searching?

- How do librarians and professors collaborate to teach students about the nature of disciplinary discourse? How do we embed disciplinary information literacy in disciplinary curricula?

- Need studies about how to motivate students to do better searching and information-gathering.

- Need more longitudinal ethnographic studies of student research habits.

- Need studies of domain learning effects on searching using search engines versus databases.

About the authors

Gary B. Thompson (MLS, MA) is Director of Library and Audiovisual Services at Siena College in Loudonville, New York. He has over forty years of academic library experience including instructing students about information literacy at the college and university levels. His mentors were Evan Farber and Hannelore Rader, two pioneers in library instruction. He can be contacted at thompson@siena.edu

Jonathan W. Lathey (PhD) is a retired school psychologist and a retired adjunct reference librarian. He has wide interests including cognitive development, public history, writing, and information literacy.