Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19-22 August, 2013

Information literacy practices and student protests: mapping community information landscapes

Sonja Špiranec and Denis Kos

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Information and Communication Sciences, Ivana Lucica 3, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

Introduction

Information literacy is an extensively discussed, researched and a commonly accepted concept, especially in the LIS field. As an offspring of the information/library community, information literacy went through a long-lasting process of growth in theoretical and applied understanding and started to spread through different communities. Although information literacy is promoted as critical to personal and societal development, in many aspects it fails to transcendent the information and library community. The one domain that has developed a stronger focus for the subject and implemented it on a wider scale is education. This comes at no surprise since information literacy was, from its very beginnings, defined and promoted by using terminology from pedagogy and education; as visible in the often-cited construct about “information literacy as a prerequisite for lifelong learning”. On a pragmatic level, information literacy standards and frameworks (ACRL 2000; Bundy 2004; SCONUL 2011) that define attributes and learning outcomes facilitated integration and penetration of information literacy into the educational domain. Although standardization enables the effective integration of information literacy into formal education curricula, a major downside to these endeavours is a limited perception of information literacy as a neutral process which is entirely unaffected by any kind of social, political or historical background (Webber and Johnston 2000). However, even information literacy standards, although being criticized for breaking down information literacy into discrete skills, imply a broader understanding and perspective by linking information literacy to lifelong learning and empowerment to make informed choices throughout life, and not only during formal education. In particular declarations and proclamations, such as the Alexandria Proclamation (2005) or the Moscow Declaration on Media and Information Literacy (2012) address information literacy as a mean to cope with the diversity of different context in information literacy, in particular social context and social challenges as part of information literacy. These documents perceive information literacy as a mean to empower people in “all walks of life” to achieve their personal, social, occupational and educational goals, and resolve problems effectively in every facet of life. In other words, a common core assumption is the diversity of context, facets and situations to which information literacy applies. The question remains, however, how information literacy is supposed to be imparted, how it is acquired or systematically developed in the variety of potential contexts that emerge in „all the different walks of life“? To stretch the variety of contexts, information literacy is understood in a generic sense, as a set of abilities that, once learned, are by default transferred to novel situations and contexts. However, this implicit assumption of the information literacy concept is yet to be examined and tested.

Theoretical frameworks of the study

In the following, we will provide an overview of theoretical frameworks for the study of student protests, which we perceive as an example of community information literacy landscape. Since student information practices, developed in the education landscape, are being viewed in the specific situation of their transition and application to another information literacy landscape, the question of transferability between different landscapes also emerges as a guiding construct for this study. Therefore, the concept of information literacy landscape as defined by the work of A. Lloyd will be explained. Since the notion of information literacy landscapes is situated within the framework of information literacy as a socio-technical practice, the main assumptions of this wider theoretical lens will be explained first.

information literacy as a socio-technical practice

The roots of understanding information literacy as a socio-technical practice occur in writings which present a radical alternative to defining information literacy merely as a set of generic skills common to all disciplines and learning environments. Authors as Marcum (2002) or Kapitzke (2003) claimed that literacies are related to historically and contextually defined social values and technologies, and that it is therefore necessary to include the various contexts of information knowledge production in the discussions on information literacy. Such claims have led to identifying information literacy as a socio-technical practice, which makes crucially important the social, ideological, and physical contexts and environments in which information and technical artefacts are used (Tuominen, Salvolianen and Talja 2005). Within such interpretations, context communities and settings are at the forefront of research and analysis of information-focused activities, i.e. information practices.

The theoretical discourse brought about the socio-technical viewpoint endorses a framework relevant for analysing information practices of students in situations of protest and dissent. Students as a group become information literate in a specific knowledge domain situated within the formal educational system. According to the generic viewpoint where transferability of information literacy is assumed, students would apply information practices gained in the educational landscape in the context of student protests. In other words, the perception of information literacy as a generic attribute implies that learners simply transfer information practices from one situation to the other. As opposed to the generic framework, the socio-technical viewpoint implies that information practices cannot be taught for life, independent of the practical domains and tasks in which they are used (Tuominen, Salvolianen and Talja 2005: 331). Students, when demonstrating and protesting for their rights, deploy information practices for tasks very different from and not belonging to the knowledge domain within formal education; they use them for very specific tasks oriented towards engagement for one’s own rights and the rights of the whole group. This situational context is determined by goals, relationships and socio-technical configurations that differ from situations and work-related tasks occurring in the arena of formal education. In accordance with understandings endorsed by the socio-technical framework, information practices from the educational environment will not automatically be transferred and applied in situations of protests and demonstration because both contexts are very different.

Student protests as an example of community information literacy landscapes

A. Lloyd (2010) has proposed the idea of information literacy landscapes as a critique of defining information literacy solely as a series of de contextualized skills. She defines three broad information literacy landscapes: the educational, workplace and community landscape. information literacy landscapes are characterized by different topologies, climates and complex ecologies. They can be interpreted depending on which information we have about them and which new information we can learn about them. Thus, becoming information literacy requires a person to engage with information within a landscape and to understand the paths, nodes and edges that shape that landscape. Lloyd states that over time, people learn to read their landscape by developing specific and appropriate information practices that allow them to interrogate it, and to use its resources (2010: 139). If becoming information literacy is bound to a landscape, then, according to Lloyd, obviously becoming information literacy in one landscape does not automatically mean becoming information literacy in another landscape. A major feature of the concept of information landscapes is the human factor, which implies a shift from limiting information literacy to textual sources. Lloyd states that landscapes are spaces created by people who co-participate in a field of practice. All landscapes are maintained through membership.

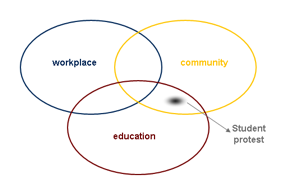

Community landscapes, among the three landscapes identified by Lloyd, are the most complex and difficult information literacy landscapes to characterize. Partridge, Bruce and Tilley define this landscape as the application of information literacy in community context and people’s experience and engagement with information within the context of the everyday life (2008: 112). It is a very diverse and vibrant landscape, as opposed to information literacy in the educational sphere, which is usually structured, attuned to a curriculum, formal and focused on scholarly, educational and mainly textual information sources. Our main theoretical point of departure is that student protests represent a specific case where students act simultaneously in two contexts. In the case of protests and demonstrations, they find themselves in a type of context situated at the intersection between educational and community information literacy landscapes, as shown in Figure 1.

As seen from figure 1, we do not perceive the three information literacy landscapes as separate entities; they vary in some aspects, in other they overlap. Student protests are situated in the space where education and community landscapes intersect. If we take Lloyd's assertion that landscapes are maintained through group membership, then students as a group act within the educational landscape. However, in situations when students demonstrate and raise their voice for student rights, which are part of civic rights, they start to engage in the community landscape, which makes them an interesting subject of study. The idea of information literacy landscapes with users immersed in one particular landscape leads to the question of transferability. Are information practices learned in one landscape automatically applied in other landscapes? Such a question seems of particular interest when comparing two substantially different landscapes, like educational and community landscapes. While the first one is characterized by defined structures and a clear focus provided by standards, frameworks and methods of assessment, in particular when information literacy is compulsory and integrated into the curriculum, the community landscape is characterized by more unstructured and unsystematic approaches. Although the narrative of community landscapes focuses on lifelong leaning, empowerment and critical thinking, it is hard or impossible to devise focused frameworks, curricula or precise learning outcomes for attaining these goals due to the heterogeneity of users, interests and goals that determine the notion of community. Examining information practices of students within the community information literacy landscape while they are simultaneously involved in formal educational information literacy landscape may contribute to our understandings of information literacy transferability and provide further insights on differences between educational and community information literacy landscapes.

In this paper, protests, demonstrations and other forms of student dissent are interpreted as an expression and manifestation of engagement for rights, student rights as well as broader civic rights. There are several resources that discuss relations of information literacy and civic engagement and give leverage to discussing civic participation as part of the community landscape. The American Library Association states that information literacy isn't a tool that can only be employed for academic, but also for social empowerment (in Owusu-Ansah 2005). Correia (2002) shared similar thoughts by arguing that information literacy enables people to interpret and act on information and to participate in community affairs, develop community involvement and have an informed opinion about problems occurring locally, nationally or internationally. With this perception, student protests fit into understandings of community information literacy, which by default, according to a recent writing of Partridge, Bruce and Tilley (2008:111) encompasses an interest in those who are relative disempowered and interest in real people facing real life problems.

Background of the study

Students are a social group typically identified as part of the educational landscape, but are, in the context of our study, examined in the situation of civic participation, i.e. as acting within community information literacy landscape. The study was conducted at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (FHSS), which, in contrast to the other faculties at the University of Zagreb, stands out by its student’s activism. Student protests at the FHSS has marked the last decade with the organization of one big (the faculty was taken over by students for a month) and a few minor blockades of the faculty building . The last protest was organized in October, 2011 and lasted for two weeks. Several students blocked the entrance to the student administration centre and the deans quarters to symbolically state that they block the place which „takes“ money from students. The blockade was presented as a part of a wider struggle for free education. It has been organized based on students’ decision to disobey the financial obligations imposed on them by an Agreement they signed at the beginning of semester (this document says that a student will pay for the expenses of his studies if the ministry in charge fails to do so). Students that were not affected by this Agreement joined the protest out of solidarity and the feeling of emancipation. In our study we tried to examine their relationship towards information in a situation when they are being exposed to a vast number of different and contradictory information.

The study

Research questions

The study examines the concept of student information literacy practice during student protests which is perceived as an information context situated within community information landscapes. The concrete research questions that drive this study are:

- How do students obtain information about their rights?

- what kind of information sources are student using in protests and why?

- are their information choices different from choices they were taught to make in educational settings?

More broadly, the study seeks to contribute to a better understanding of differences between education and community information literacy landscapes as defined in Lloyd (2010) by exploring information practices within the community information landscape, i.e. the subset of practices referring to civic participation in the context of student protests. Since students usually act within the formal educational landscape the study also touches the issue of transferability of information literacy practice from one, very formal and defined landscape, to another, undefined and informal landscape.

Collection and data analysis

Data was collected from June to August, 2012 on the sample of 340 students. The sample consisted of students attending the first and the third year of BA programs on the FHSS in Zagreb. The sample was structured in this way to include responses from students that have merely started their studies and students that were finishing their BAs This allowed insight into differences provoked by the length of studies, different understandings of information literacy and experience in information practices that characterize higher education settings. Data was collected through a face-to-face survey consisting of a questionnaire containing open and closed questions. The questionnaire contained three set of questions; the first set pertained to students and their involvement in protests, the second to understandings of information literacy, and the third to their information behaviours in situation of protests (relevant information as a trigger for participating in protests, finding information about rights, preference of information types, i.e. formal/informal, examples of use etc.) In the analysis both qualitative and quantitative methodology were used.

Findings and discussion

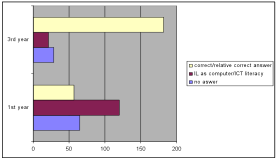

The first finding pertained to the initial assumption that students in their final year of BA, which have been more exposed to information practices in the educational domain, have gained a better understanding of information literacy. As seen from Graph 1, the degree of understanding information literacy growths with the year of study, with 3rd year students providing the least number of blank or incorrect answers. Since there is no universally accepted definition of information literacy, just explanations limited to computer literacy, internet use or technical skills were interpreted as incorrect. Such a distribution of responses was expected since students in their final year of BA programmes are more experienced with information, information concepts and had the opportunity to gain understanding of the information literacy concept (usually during the 2nd or 3rd year of study, within information literacy courses offered at the Faculty).

Furthermore, we were interested in the sub-group of the sample who participated in student protests and compared their responses to students who did not participate. More specifically, we analysed their specific relationship towards information as an impulse for making decisions on participation in diverse forms o student dissent. The differences are visible in Table 1 and 2.

| Was your decision to participate based on relevant information? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not sure | No | Partly | Mainly | Absolutely | Total | |

| 1st year | 72 (34%) | 31 (15%) | 46 (22%) | 45 (21%) | 18 (8%) | 212 |

| 3rd year | 30 (23%) | 17 (13%) | 39 (30%) | 30 (23%) | 12 (9%) | 128 |

| Total | 102 (30%) | 48 (15%) | 85 (25%) | 75 (24%) | 30 (9%) | 340 |

| Was your decision to participate based on relevant information? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not sure | No | Partly | Mainly | Absolutely | Total | |

| 1st year | 6 (20%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 10 (33%) | 10 (33%) | 30 |

| 3rd year | 0 | 2 (2%) | 10 (10%) | 58 (56%) | 34 (35%) | 104 |

| Total | 6 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 13 (10%) | 68 (51%) | 44 (33%) | 134 |

As indicated by table 1 and 2, the more experiences students have developed during their studies, the more they rely on information in their decision to participate in protests. The percentage of uncertainty relating to relevant information as a trigger for action drops with more experience and greater involvement in the educational landscape.

Moreover, significant differences are visible in figures elicited on the total level of all answers; students who engage in civic actions and demonstrations are less uncertain about the importance of information compared to students who do not participate (4% in comparison to 30%). Also, for this group of students relevant information is an absolute prerequisite for taking actions (33% of students who participate in protests compared to 9% of students who do not participate). From this we may conclude that students who engage in protests and are active in community information literacy landscapes have developed strong attitudes towards information and take relevant information as a point of departure for action.

The next set of questions pertained to the type of sources students use when making decisions about participating in protests or other kinds of dissent. As shown in Table 3, when engaging in community landscapes as opposed to formal educational landscapes, they rather use non-formal resources or a combination of non-formal and formal resources instead of using formal sources, as they where thought to do in formal educational settings. From these figures it may be discerned that the choice and preference of sources is not spontaneously transferred from one landscape to the other, but rather depends on specific needs, features and requirements of the respective landscape.

| Types of information sources preferred when deciding to participate in protests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal | Informal | Formal and informal | |

| Students engaging in protests | |||

| 1st year | 2 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 26 (87%) |

| 3rd year | 5 (5%) | 15 (14%) | 84 (81%) |

| Students not engaging in protests | |||

| 1st year | 19 (17%) | 39 (18%) | 154 (73%) |

| 3rd year | 6 (5%) | 23 (18%) | 99 (77%) |

Although table 3 indicates some preferences of the respondents in using formal/non-formal information, these percentages do not provide specific details about the kind of sources used, context of use or how students found out about these sources. To obtain a clearer and more precise picture, the questionnaire used in the study contained open questions regarding the type of formal/non formal sources used, illustrations of situations in which students use them, as well as who pointed them to the source. A sample of answers is provided in table 4 and 5; the most frequently provided responses are marked boldface.

| 1st year students |

|---|

| Types of formal sources used: internet portals, official publications, student (administration) office, databases Types of informal sources used: word of the mouth, social media |

| Examples of use, reasons for using the sources: „when I can't obtain information through formal sources, I use informal sources“ „If formal sources are not understandable and complicated, I go to informal sources“ „Formal – when I deal with a serious situation, when it comes to important stuff“ „Formal: when it's about my civil or student rights, non-formal: when it's about insignificant things“ „Of course I use formal, you don't expect me to believe informal sources???“ „Informal sources are my second choice“ „Formal – for checking informal sources“ “When it comes to student protests, I use formal sources” |

| Who/what pointed you to these sources? Internet search engines, other colleagues, professors |

| 3rd year students |

| Types of formal sources used: internet sources, student administration offices Types of informal sources used: word of the mouth, social networking sites |

| Examples of use, reasons for using the sources: „If informal are not credible, then both“ „Formal – when it is about my rights“; Formal – if it is about student protest“, „“formal- if my rights are inhibited“ „Informal – when I want to know what other people think“ “Informal-when I don’t have time“ “I use informal sources as a starting point“ “I always use formal because they are more credible“ „When I need a quick answer I use informal ones“ |

| How did you find out about the sources: internet, students professors |

| 1st year |

|---|

| Types of formal sources used: official publications, internet portals, mass media (news) Types of informal sources used: word of the mouth, social networking sites |

| Examples of use, reasons for using the sources: „I choose informal when I have no other choice“ „When I have serious problems, questions about tuition fees than I choose formal sources“ „Informal-when I am curious“ „If it is about demonstrations, I choose non-formal sources“ „Informal—as a starting point, formal, if I wan complete information“ „Formal if it is personal, informal if it concerns the whole group“ „Before I take actions, I check things in formal“ „Always informal“ |

| How did you find out about the sources: internet search engines, colleagues and other students, professors, media, friends |

| 3rd year |

| Types of formal sources used: internet portals, faculty administration, print sources Types of informal sources used: mouth-to-mouth, social networking sites |

| Examples of use, reasons for using the sources: |

| „When arranging and agreeing upon protests and actions with colleagues, I use informal resources“; „When it is about student actions and protests, I use informal sources“ „I use informal sources when I need information about matters of common interest“ „Non-formal sources are more reliable because formal sources are full of bureaucratic empty phrases“ „I never use formal sources“ „I use formal when I need objective information, when I am interested in experiences and attitudes of students I use informal“ „I use informal sources as a starting point“ „During student actions and protests I use informal sources“ „I use both in order to get the complete picture“ “I use formal sources when my personal rights are inhibited“ „I use informal sources for personal investigation, but when I have to prove my arguments that I use formal sources to back them up“ “When official information make no sense, I ask my colleagues“ |

| How did you find out about the sources: internet search engines, colleagues and other students, professors |

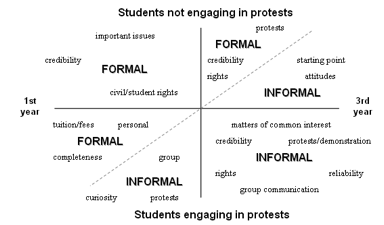

A qualitative analysis of the responses elicits further insights about source selection and use during student protests. First year students rely more on online sources, both formal and informal, probably because they have not built a trustable network of colleagues yet, and focus therefore on accessible online sources. More obvious differences in explanations for using particular sources are visible between students who participate in protests as opposed to students who do not participate. The responses indicate that students who participate in forms of student dissent tend to use informal sources much more often. In general, a more positive attitude towards informal sources is visible among students who participate in protests, while students who are not participating in protests are inclined to use formal sources when it comes to their rights or when they need credible sources. The distribution of answers based on qualitative analysis is shown in Figure 2.

In some aspects, such a distribution seems surprising. One might expect that 1st year students, who are less experienced with the academic landscape, would prefer to use informal sources, while 3rd year students, as more experienced users of information who are deeply involved in the educational information landscape would prefer to use formal, and thus more credible and reliable sources. However, the distribution shows that the use of sources correlates to the context of use, and that information practices do not automatically transfer from one landscape to the other. A possible explanation for this shift might be that for students who participate in protests official, formal sources and publications are sources „released“ by opponents they are protesting against; like the Ministry, university administration or media who are governed by the establishment. In other words, when acting in the educational information literacy landscape, students associate credibility with official, formal and scholarly information, while for students immersed in community information literacy landscapes credible information is the one not generated or released by formal or official instances. Credibility issues are paramount in situations of crisis and confusion, including demonstrations and protests. For example, in the case of protests that were the subject of our study contradictory information from different sources was available, e.g. information disseminated by official authorities the protests were directed against, information disseminated by different student organizations which either support or refuse protest, information published by faculty administration, information disseminated by individuals via social media etc. Deciding which information to trust in situations when a variety of information from different sources is available is critical for acting upon information and can shape the nature and outcome of protest.

The results of the study have also highlighted „group thinking“ and „common interest“ as a significant feature that differentiates community information literacy landscapes in situations of civic engagement from common educational contexts. While students who are not engaging in protests are self-focused and emphasize personal interest, in the community information literacy landscape common and group interest, communication and sharing are perceived as more important.

Conclusion

The aim of the study was to contribute to a better understanding of differences between education and community information literacy landscapes defined by Lloyd. In particular, it serves as a point of departure for characterizing the most unstructured and least coherent landscape, the community information literacy landscape. Due to undefined boundaries, wide information scopes and variety of communities belonging to this landscape, conceptualizing information literacy within such a space is a complex issue. It also raises the question of application and transfer of information practices from one landscape to the other.

In this paper, the authors have tried to address the described issues by comparing information practices of students in education and community information literacy landscapes, i.e. in a specific sub-context, the context of student protest. During protests and demonstrations, students stand up for their rights and demonstrate civic responsibility and engagement. These processes are informed by students’ ability to find, accesses, evaluate and use/communicate/share information. An initial assumption of this study was that students in their final year of BA have developed a better understanding of information literacy due to affordances of their studies. However, the results of the study have shown that these students have not developed significantly different attitudes to information or use different type of sources compared to their younger colleagues. Differences that are more significant are visible when comparing groups of students who do or do not participate in protests. Such findings lead to the conclusion that information practices are informed by the context in which they are applied, and are not transferred automatically from one context to the other.

The results of this study also allow for further characterizations of the community information literacy landscape, in particularly when it comes to the context of protests, which are situated in the wider context of civic participation and engagement. As shown in the study, as opposed to educational information literacy landscapes, during protests student tend to:

- use in-formal sources of information

- use non-textual information

- use colleagues as sources of information

- act upon „common“ interest of the group

In other words, community information literacy landscapes, when analysed in the context of civic engagement, are characterized by informal sources, social dimensions of information and group/community interest. As opposed to the information landscape of formal education, information is not perceived as an object to be found, located and used by the individual who uses a set of predefined proper strategies. People and communities are sources of information as well, and information practices are undertaken with the „common“ interest of the group in mind.

The findings also suggest that existing information literacy practices deployed in the educational landscape are confined to the respective sphere, without overcoming boundaries of this sphere. Students obviously use one set of information practices in one context, and another set of practices in another. From this it may be discerned that information literacy in sessions provided in educational context should be conceptualized and performed differently and wider in scope. More references and reflection regarding to information practices in other landscapes are needed in order to assure future transferability, as to how to find, evaluate, use and communicate information in workplace or community information literacy landscapes.