Information seeking behaviour of parents of paediatric patients for clinical decision making: the central role of information literacy in a participatory setting

Petros Kostagiolas

Department of Archives and Library Science, Ionian University, Corfu, Greece

Konstantina Martzoukou

Department of Information Management, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland

Georgia Georgantzi

Department of Paediatrics, Attikon General University Hospital, Athens, Greece

Dimitris Niakas

Hellenic Open University, Faculty of Social Sciences, health care Management, Patras, Greece

Introduction

The Internet influences the way we make decisions or share issues to make decisions for ourselves and for our loved ones. Parents use the Internet as a significant information resource about their children's health and wellbeing. They are, however, faced with a wealth of information and a constantly expanding and unregulated information space, which creates many challenges but also offers many new opportunities (Zhao 2009). The Internet may act as both a facilitator and a barrier. As parents use more, easily accessible sources of information and fewer traditional 'gatekeepers' of medical knowledge, they may feel more empowered and involved in their children's health care. On the other hand, health information found online may lead to an overload of misleading or unreliable information.

Research has found that using the Internet helps parents collect additional information after a consultation with a medical professional, draw support from online groups/forums and increase their awareness of alternative therapies (McMullan 2006). In addition, information found online may be utilised as a supplement to more formal or regulated health services (Bouche and Migeot 2008). Parents also use the Internet to complement or even replace more traditional methods of interpersonal communication, which may offer a significant source of emotional support (Wikgren 2003). On the other hand, online health-information seekers may be less satisfied with the health services/systems (Tustin, 2010) and may rely more on self-care instead of medical care (Wagner 2001). Increased awareness can evoke negative emotional reactions such as information anxiety, fear and uncertainly (Gage and Panagakis 2012) as well as a feeling of personal responsibility to keep up-to-date with all the new medical advances.

There has been much research on the information seeking behaviour of medical professionals, but relatively little research has addressed the impact of the Internet on parents' general health information seeking behaviour and more specifically how such information seeking influences their attitudes towards and their relationship with health care providers/services. There is however, a growing research interest in parents' health information needs with children who suffer from specific chronic medical conditions (Hummelinck and Pollock 2006) such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Sciberras et al. 2010), cancer (Kilicarslan-Toruner and Akgun-Citak 2012) and Autism Spectrum Disorders (Mackintosh et al. 2006). These studies provide a useful insight into the specific information needs of parents and offer some understanding of parents' information seeking behaviour in their effort to make informed decisions about their children's health care. For example, emphasis is given on the importance of good communication with health professionals, highlighting the provision of quality information as "a prerequisite for a genuine partnership" (Hummelinck and Pollock 2006: 228). Furthermore, the richness of information needs is not always addressed by medical professionals and effective information provision may require an individualised approach that is tailored to the needs of parents and their children. Overall, it is clear that the Internet has not only restructured the process parents go through to answer their health related information needs for their children but has also reshaped the relationship between parents of patients and medical professionals.

Perhaps many of the findings on information needs and behaviour that apply to specific chronic medical conditions may not be applicable in the context of other acute illnesses or in the context of parents' everyday information seeking behaviour for health related information (which may require less medical intervention or consultation). What is apparent from the literature is that parents of paediatric patients are a special group of users with extra anxiety and an added responsibility as care-givers, a role which requires additional reassurance and guidance. During the process of information seeking on the Internet, parents are presented with a variety of information related to specific medical conditions but also to other more general interlinked health issues (e.g. growth and development, nutrition, immunisations). They are exposed to a lot of information on different levels which may require professional verification that is not always possible within the restricted time frames allowed in short consultations with doctors. Recent research, for example, has found that parents prefer trusted sources (e.g. paediatricians) to accessing Internet information because this may create insecurity and fear of encountering untrustworthy information (Gage and Panagakis 2012, Sciberras et al. 2010, Wainstein et al. 2006) or confusing information which is not geared at the right level for their children (Bernhardt et al. 2004). This creates the need for information literacy education and additional information services as support mechanisms for both the parents and the paediatricians. Information literacy means "knowing when and why you need information, where to find it and how to evaluate, use and communicate it in an ethical manner"(CILIP 2013). Within the context of health consumers' information seeking, health literacy has also been defined as "the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions" (Institute of Medicine 2004). There is still a lot to understand about parents' health information literacy, the impact of their information-seeking behaviour on their interactions with health care providers, how this process has reshaped doctors' traditional roles and how to best support informed and participatory health decision-making.

Aims and objectives

The present study examined the health information needs and information seeking behaviour of parents of paediatric patients based on data collected from a paediatric department of a university hospital. The research explores a range of information needs that lead parents to seek medical care (e.g. diagnosis, routine examinations, prevention, growth and development, prognosis, parenting, child's nutrition), the information sources that influence their health decisions (health-care professionals, Internet/search engines, medical websites) and their frequency of seeking health information online. The study also examined the reasons that parents seek paediatric health information (e.g. for further information, to reduce anxiety, to enrich understanding, because of insufficient time spent with a doctor or to establish contact with other families) and a number of limitations associated with consulting both online health information sources and medical professionals (e.g. lack of time or organised information and unfamiliarity with information sources). Particular emphasis was given to understanding and discussing the role of information literacy in shaping a participatory parent-paediatrician relationship and how parents independently seek information before or after a medical consultation with their doctor.

This research is based on the premise that the Internet and other information resources enable patients to become more informed, empowered and active participants in the clinical decision-making process about their health condition, creating a stronger, more patient-centred patient-doctor relationship (Coulter and Collins 2011; Murray et al. 2003). Previous research has found that medical professionals may be afraid of losing their unique position as the gatekeepers of medical knowledge and have concerns about their communication with patients. They also experience difficulties adjusting to their new role of the information verifier (validating the information retrieved by the patient) (Koch-Weser et al. 2010). Thus, there is a need to model and further study the relationship between patient and doctor where the patient, empowered by information, plays an active and equal role, participating in a shared clinical decision-making process, while the doctor extends their role to that of an information verifier (Coulter and Collins 2011). By extending their roles to address the new needs of patients, medical professionals can become catalysts or enablers that support and encourage parents to look for and retrieve health information. According to Walker, catalysts provide "positive experiences, such as the knowledge of being listened to and easy access to relevant information" (Walker 2009: 57). Furthermore, research has demonstrated that patient satisfaction which arises from empathy by the health provider and the quality of time devoted to the patient, influences that patient's decision to choose the health provider as a preferred information source (Tustin 2010).

Methods and theoretical framework

Theoretical construct of the survey

The data of this study were collected by a questionnaire which was distributed to parents of children admitted as patients at the paediatric department of a university hospital between February and April 2012. During the survey period all parents with scheduled appointments in the clinic were approached. The university hospital is one of the newest and larger university hospitals in the southeast Mediterranean region and includes a wide range of specialised health care units and research centres, providing a high quality of services. In particular, the paediatric clinic is a distinguished university clinic with research activities. The survey was approved by the scientific committee of the University Hospital as well as by the director of the paediatric university department. Before its distribution, the questionnaire was evaluated by a group of experts from both the paediatric and the information science academic communities. Out of the 216 parents approached, 121 agreed to participate in the survey and completed the questionnaire, achieving a response rate of 56 per cent.

The questionnaire has been informed by theory developed by Wilson which advocates a more person-centred approach, focusing on the 'human aspects of information use', information needs and the context, i.e., the situation in which information needs arise and the barriers which may influence information seeking behaviour (Wilson 2000: 50). According to Wilson's macro model of information behaviour, information seeking is viewed as an effort to satisfy a set of primary interrelated physiological, cognitive or affective needs which are triggered by the demands created within a set of contexts (e.g. individual, work and life, or the wider physical, socio-cultural and politico-economic environment). Within these contexts, individuals play a range of intertwined roles and may encounter a variety of different barriers, which can be personal, interpersonal or environmental. These act as hindrances to information seeking and obstruct the progress towards addressing primary needs. Wilson also theorised that information seeking behaviour is a problem-solving activity driven by goals which are created within a range of contexts in which the person operates. Therefore, the stages of the information seeking process describe phases in problem resolution within those contexts (Wilson et al. 2002). Wilson's first model was subsequently expanded and revised to provide a more effective general framework that can be more specifically elaborated with emphasis to particular user groups and situations. In Wilson's 1997 model, barriers were replaced with 'intervening variables' (preventive and supportive) on the premise of examining both obstacles and enablers in relation to information seeking. The intervening concepts can be psychological, demographic, role-related, interpersonal, and environmental. As extension to the intervening concepts a number of additional theories were added (i.e.. stress/coping theory, risk/reward theory and social learning theory) which may also be of interest for health information seeking but are beyond the scope of this paper (Wilson 1997).

This research study has therefore examined the information seeking behaviour of parents in relation to their roles as both care-givers and actors in clinical decision-making for their child, the circumstances and motives that give rise to their specific information-seeking behaviour (i.e., their different health information needs which relate to the health of their child), and the intervening variables which may act as barriers or enablers to their information seeking. Information seeking is viewed as a problem-solving activity geared towards the clinical shared decision-making process and therefore the resolution of a specific health related problem/issue. The research also sought to examine the impact of Internet information seeking on patient-doctor interactions which may shape the process of shared decision-making. Therefore, the questionnaire (provided in Appendix 1) is mapped to Wilson's framework as follows:

- The first section includes questions about the demographics of the parents (sex, age, education) and their accompanied child (sex, age, health condition) as well as the hospital visitation characteristics (i.e., chronic or non-chronic illness, reason for visiting the doctor and number of previous visits).

- Information seeking behaviour is initiated by recognition of information needs that are identified within a particular setting, i.e., the roles and the environment of parents and paediatric patients. The second questionnaire section includes the needs for information seeking identified by the parents of paediatric patients in relation to their 'role' as parents. This includes the totality of experiences they have as information users within their parental role and the environment in which this role is realised.

- Within the information universe parents are in contact with a number of different information resources including other persons (family or the doctor) and 'technology' systems, including the Internet. The third section concerns Internet access questions and the reasons that make parents turn to technology information systems for satisfying their information needs and more specifically to the Internet. In this particular context these are related to the relationship that parents have with their doctor, communication and their needs to seek further information.

- The next questionnaire section assesses the use of digital (including the Internet), conventional and interpersonal information resources which are examined in terms of both their usage and influence on clinical decisions made for the child.

- The fifth section of the questionnaire assesses the importance of intervening variables (barriers/obstacles) to information seeking which may be personal, interpersonal and environmental.

- The final section of the questionnaire goes beyond the framework of information seeking behaviour of Wilson although it is related to the fruitful discussion for research motives in (Wilson 2006). Therefore, it includes the impact of information seeking on the satisfaction of information needs, patient-doctor interactions and decision-making patterns.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data on reported information behaviour. Further analysis, centred on the differences in reported behaviour by the parents and their accompanied child's characteristics, was performed using Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. In this paper only statistically significant results are reported.

Internal consistency of survey items

A five-point Likert scale was used to rate information needs employment (fourteen items), the reasons for seeking health information on the Internet (nine items), information resources (ten items) utilisation and their influence on clinical decision making, the importance of barriers involved in seeking information (eight items) and finally the impact of information on clinical decision-making patterns. The values assigned to the five item Likert scale ranged from 1=not at all indicating the lowest score to 5=a lot which was assigned the highest score.

Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient is a measure of the internal consistency of the items in the scale. The closer it is to unity the greater the internal consistency of the scale employed. The size of Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient is determined by both the number of items in the scale and the mean inter-item correlations where N is equal to the number of items, c-bar is the average inter-item covariance among the items and v-bar equals the average variance:

If the value of alpha is greater than 0.9 the internal consistency is judged as excellent; greater than 0.8 is good; greater than 0.7 is acceptable; greater than 0.6 is questionable and greater than 0.5 is poor. Values less than 0.5 are unacceptable ( George and Mallery 2002). In general, an alpha above 0.7 is probably a reasonable objective although it should also be noted that while a high value for Cronbach's alpha indicates good internal consistency of the items in the scale, it does not mean that the scale is unidimensional, which is judged by factor analysis.

The fifty-five-item questionnaire scales had excellent internal consistency reliability with overall Cronbach alpha of 0.934; and no variable influenced the scale mean and the overall Cronbach alpha if it were to be removed from the model. The reliability of each subscale was as follows: information needs utilisation=0.873, reasons for using the Internet=0.770, information resources utilisation=0.736, information resources influence on decision making=0.852, importance of the barriers involved in seeking information=0.714 and impact of information on decision-making patterns and patient-doctor interactions=0.527. In Appendix 2, the item-analysis outputs from SPSS for the multi-item questionnaire subscales are analytically presented in different tables for each of the subscales. Each table of Appendix 2 includes:

- summary of statistics (mean, minimum, maximum, range, maximum/minimum, variance) for all subscale item means, item variance, inter-item correlation and inter-item covariates which provides descriptive information about the correlation and covariance, respectively, of each item with the sum of all remaining subscale items;

- item-total statistics (Scale mean if item deleted, Scale variance if item deleted, Corrected item-total correlation, Squared multiple correlation and Alpha if item dDeleted);

- the subscale's Cronbach's alpha coefficient of internal consistency with the number of scale items (the Standardized Item Alpha is omitted since all individual subscale items are scaled in the same manner).

The analysis of Appendix 2 indicates that removing any of the items does not reduce or increase internal consistency making any of the subscales less reliable. The only notable comment would have to do with Tables 3 and 4 of Appendix 2, for the subscales information resources utilisation and information resources satisfaction in regard to the item medical staff. If this item were removed the subscales' reliability would be slightly increased, however, the original internal consistency is adequate and the item should be kept for theoretical reasons (as medical staff are an important interpersonal information resource). Therefore, all the items should actually be kept and the internal consistency of the subscales is found to be good or very good with no problematic variables, while the last subscale has only a marginally adequate Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient. This last section of the questionnaire is quite relevant and may indicate the need for further research relating to the impact of the Internet on health information seeking, in particular information use for shared decision-making.

Statistical methods of analysis

The initial analysis consisted of descriptive statistics to summarise the main features of the data collected. Further analysis was performed on the differences in parents' information seeking behaviour, the obstacles they encounter and their perceived impact of the retrieved information in relation to demographic characteristics (of parent and child). There were two statistical tests used in this analysis: the Mann-Whitney U test which was employed for assessing the differences between two groups and the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks test, which was used for examining the differences between more than two groups in the key areas for the study (both analyses were based on mean rank values). More analytically, the tests addressed differences between parents'/children's demographic characteristics (e.g. parents of children with chronic or non-chronic and acute or non-acute health problems; educational level of parents and history of visits) and the following variables:

- parents' information needs;

- their reasons for using the Internet;

- their frequency of using different information sources;

- the level of importance they assign to different information resources for making health decisions;

- the obstacles they encounter in information seeking;

- the impact of information on the relationship between parents and their doctors.

Statistical data analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows (version 20) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). In this paper only statistically significant results have been reported.

Limitations

As the survey was conducted on one specific socio-economic setting, the results should be generalised with caution because they may not be directly applicable in other settings and countries. However, they offer a useful insight into how parents seeking information on the Internet may influence their relationship with their doctors in clinical decision-making and can be useful for follow up research studies that aim to explore these issues in more depth.

Survey results

Demographic data

Table 1 summarises the demographic characteristics of parents (sex, age, profession and education) and their accompanied child (sex, age, health condition) as well as the reasons for visiting the hospital (i.e., chronic or non-chronic illness). Although there was a higher percentage of women in the sample this result is not surprising given that the mother of the child is usually the main accompanying person during hospital appointments. The majority of those who participated in the research described the condition of their child as a non-chronic health condition (51.9%). Chronic health issues were related to neurological medical conditions, such as epilepsy (13.2%), respiratory disorders, such as asthma and bronchitis (13.2%) and other chronic illnesses, such as allergies or relapsing infections (5.8%). Most of the parents (76.9%) stated that the reason for visiting the paediatric clinic was acute illness (such as fever, seizures, vomiting) and the remaining had a follow up therapeutic or diagnostic appointment with a doctor (23.1%).

| Parent | Accompanied child | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Sex | ||

| Female | 89 (77.4%) | Male | 68 (57.6%) |

| Male | 26 (22.6%) | Female | 50 (42.4%) |

| Age | Age | ||

| ≤ 24 | 4 (3.5%) | ≤ 2 | 39 (33.6%) |

| 25-35 | 54 (47.4%) | 3-6 | 39 (33.6%) |

| 36-45 | 44 (38.6%) | 7-12 | 32 (27.6%) |

| ≥ 46 | 12 (10.5%) | ≥ 13 | 6 (5.2%) |

| Education | Health Condition | ||

| High school | 48 (42.5%) | Non-chronic | 42 (51.9%) |

| Post-high school or technical | 38 (33.6%) | Chronic | 39 (48.1%) |

| University or higher | 27 (23.9%) | ||

| Reason for visit | |||

| Acute illness | 83 (76.9%) | ||

| Therapeutic/diagnostic appointment | 25 (23.1%) | ||

| Number of previous visits | |||

| First visit | 79 (66.4%) | Second time | 19 (16.0%) |

| More than twice | 21 (17.6%) | ||

Parents' information needs and motives

Table 2 presents the frequency of information seeking of parents related to different information needs. High and very high frequencies were reported for issues related to the child's current medical condition (e.g. diagnosis, medication, and long term prognosis), for potential diagnoses (i.e., searching for information to reduce uncertainty for illness symptoms which could be linked to multiple diagnoses) and for finding a health care provider. Parents also sought information to fulfil their needs for their child's wellbeing, nutrition and diet, growth and development. However, less emphasis was given to alternative medicine practices, general parenting issues, support groups and social networks.

| Information needs (questionnaire section 2) | Frequency of information seeking | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1 & 2) | Medium (3) | High (4 & 5) | Median value | |

| Parenting (Valid N = 116) | 28.5% | 22.4% | 29.1% | 3.00 |

| Child's wellbeing (Valid N = 115) | 25.2% | 13.9% | 60.9% | 4.00 |

| Child's growth & development (Valid N = 117) | 29.9% | 16.2% | 53.9% | 4.00 |

| Child's nutrition & diet (Valid N = 112) | 32.1% | 16.1% | 60.8% | 4.00 |

| Preventive medicine (ammunition) (Valid N = 116) | 28.4% | 12.1% | 59.5% | 4.00 |

| Finding a health care provider (MD or clinic) (Valid N = 113) | 26.5% | 18.6% | 54.9% | 4.00 |

| Potential diagnoses (Valid N = 113) | 28.3% | 14.2% | 56.7% | 4.00 |

| Regarding available treatments (Valid N = 113) | 29.5% | 21.4% | 49.1% | 3.00 |

| Alternative medicine practices (Valid N = 112) | 69.6% | 9.8% | 20.6% | 1.00 |

| Current diagnosis (Valid N = 116) | 20.0% | 13.6% | 66.4% | 4.00 |

| Current medication (Valid N = 113) | 29.2% | 15.0% | 55.8% | 4.00 |

| Long term prognosis (Valid N = 112) | 32.1% | 16.1% | 51.8% | 4.00 |

| Support groups (Valid N = 113) | 65.5% | 13.3% | 21.2% | 2.00 |

| Social networks (Valid N = 114) | 57.9% | 15.8% | 26.3% | 2.00 |

Demographic characteristics and information needs

The examination of the demographic characteristics of parents and children in relation to information needs (using the Mann-Whitney U test) found significant differences in the parents of children with different health conditions (chronic vs. non-chronic; acute vs. non-acute). In particular, parents of children with non-chronic health conditions searched more frequently than those with chronic health conditions for information on child development (the mean ranks of the groups were 46.79 and 32.30 respectively; U = 492, p=0.004) and child nutrition (the mean ranks of the groups were 44.82 and 33.29 respectively; U = 532, p=0.021). The same information needs were also prominent among parents of children with acute health conditions when compared to those with non-acute health conditions (for child development the mean ranks of the groups were 56.95 and 39.67 respectively; U = 652, p=0.012 whereas for child nutrition the mean ranks of the groups were 54.45 and 39.92 respectively; U = 669, p=0.029). An expected significant result was also found for acute and non-acute health conditions in relation to long term prognosis (the mean ranks of the groups were 47.30 and 60.63 respectively; U = 658, p=0.044).

Significant differences (using the Kruskal-Wallis test) were also identified among parents in relation to different educational levels. In particular, parents with lower educational qualifications searched more frequently for parenting issues (H(2)=6.89, p=0.032 with mean rank values 63.30 for high school education, 52.99 for technical post high school education and 43.93 for university education) and for child wellbeing (H(2)=7.35, p=0.025 with mean ranks 62.81, 51.54 and 43.46, respectively for the three parents' education categories). On the other hand, a different result was obtained for current diagnoses (H(2)=7.233, p=0.027 with mean ranks 49.27 for high school education, 62.21 for technical post high school education and 43.17 for university education).

Furthermore, there were significant differences in the number of times parents visited the medical practice when examined in relation to their information needs. Specifically, parents who visited the medical practice for the second time had more frequent information needs for finding a health care provider (H(2)=8.221, p=0.016 with mean ranks of 51.71 for first time visit, 75.47 for those with one previous visit and 57.45 for those with multiple previous visits). A similar result was obtained for potential diagnoses (H(2)=9.565, p=0.008 with mean ranks of 54.49 for first time visit, 77.18 for those with one previous visit and 46.83 for those with multiple previoius visits).

Internet access and reasons for using the Internet

The majority of the parents who took part in the survey had access to the Internet (89.8%) and used it for health care information seeking (83.8%). More than one third (37.1%) used the Internet once a week or more for health related information needs, while the rest used it between one to three times a month (29.5%), or at least once every two months (33.3%). Table 3 provides an overview of the issues motivating parents to use the Internet for health care information seeking. Parents' responses indicated that Internet use was not linked at least to a great extent with issues related to consultation with their paediatrician, thus lack of time with the doctor, embarrassment at asking, lack of understanding and unanswered questions were deemed to be of low importance. On the other hand, the survey results demonstrated that important reasons that make parents seek information on the Internet are seeking further information and (63.7%), anxiety reduction (41.2%).

| Reasons for using the Internet (questionnaire section 2) | Level of importance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1 & 2) | Medium (3) | High (4 & 5) | Median value | |

| Lack of time with doctor (Valid N = 100) | 74.0% | 8.0% | 18.0% | 2.00 |

| Embarrassment at asking the doctpr (Valid N = 103) | 90.3% | 5.8% | 3.9% | 1.00 |

| Questions not answered by doctor (Valid N = 104) | 64.4% | 19.2% | 16.4% | 2.00 |

| Did not understand answer (Valid N = 102) | 75.5% | 15.7% | 8.8% | 2.00 |

| Reduce anxiety (Valid N = 102) | 45.1% | 13.7% | 41.2% | 3.00 |

| Seek further information (Valid N = 102) | 11.8% | 24.5% | 63.7% | 4.00 |

| Belief that additional information is available (Valid N = 99) | 43.4% | 21.2% | 35.4% | 3.00 |

| Seeking alternative treatments (Valid N = 1103) | 51.5% | 15.5% | 33.0% | 2.00 |

| Contacting others with similar condition (Valid N = 101) | 71.3% | 10.9% | 17.8% | 2.00 |

Demographic characteristics and reasons for using the Internet

The examination of the demographic characteristics of parents and children in relation to parents' reasons for using the Internet (using the Mann-Whitney U test) found significant differences in the groups of parents of children with different health conditions (chronic vs. non-chronic; acute vs. non-acute).In particular, parents of children with chronic health conditions reported lack of time with doctor as a significant reason for using the Internet (the mean ranks of non-chronic and chronic health condition groups were 30.90 and 40.10, respectively; U = 451, p=0.046). A similar result was also found in the acute/non-acute health conditions groups on the basis of lack of time with doctor (the mean ranks of the groups were 39.26 and 61.61 respectively; U = 377, p<0.001).

Significant differences (using the Kruskal-Wallis test) were also identified among parents in relation to different educational levels. Specifically, parents with higher educational qualifications reported more embarrassment at asking the doctpr (H(2)=6.461, p=0.040 with mean rank values 42.38 for high school education, 50.44 for technical post high school education and 55.44 for university education). In addition, the child's age was significant in terms of lack of time with doctor (H(3)=8.583, p=0.035; with mean rank values of 46.40 for child ages less than 2 years old, 40.56 for ages between 3 and 6, 59.50 for 7 to 12 and 58.50 for 13 years of age or more).A significant result was also found for the number of parents' visits to the clinic in terms of using the Internet for reducing anxiety (H(2)=6.087, p=0.048 with mean ranks of 55.07 for first time, 36.00 for those with one previous visit and 47.48 for those with more than one previous visit).

Information sources used and their importance to medical decisions

Table 4 summarises the results of the frequency of using different information sources. The most frequently used information source were medical staff (e.g. doctors, nurses) (63.5%), followed by Internet/search engines (56.2%) and members of the family (50.9%). On the other hand, scholarly information from electronic and printed journals was not high in their preferences.

Demographic characteristics and information sources utilisation

Significant differences were identified (using the Mann-Whitney U test) for the chronic vs. non-chronic health problems groups in the frequency of using colleagues as an information source (the mean ranks of the groups were 45.83 and 34.59, respectively, U=573.5, p=0.025). Among those with acute/non-acute child medical conditions there were significant differences in the utilisation of friends as information sources (the mean ranks of the groups were 54.31 and 40.94 respectively; U = 698, p=0.041).

Significant results (using the Kruskal-Wallis test) for the parents' educational levels were also identified in relation to the utilisation of different information sources. Family was more frequently used as an information resource by parents with a lower educational level (H(2)=6.914, p=0.032 with mean rank values of 61.43 for high-school education, 47.96 for technical education and 44.37 for university education). In addition, family was a frequent information source used by male participants in the study (U=742.5, p=0.045 with mean value for men 63.3 and for women 49.78).

On the other hand, Internet (general search engines) were utilised more by parents with higher educational qualifications (H(2)=12.388, p=0.002 with mean rank 38.35 for high school, 58.59 for post high school or technical and 58.61 for university or more. A similar result was found for medical portals (H(2)=9.770, p=0.008 with mean ranks of 40.10 for high school, 57.94 for post high school/technical and 58.42 for university or more.

| Information sources (questionnaire section 3a) | Level of frequency of use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1 & 2) | Medium (3) | High (4 & 5) | Median value | |

| Medical staff (Valid N = 107) | 21.5% | 15.0% | 63.5% | 4.00 |

| Internet (general search engines) (Valid N = 105) | 24.8% | 19.0% | 56.2% | 4.00 |

| Medical portals (Valid N = 107) | 54.2% | 13.1% | 32.7% | 2.00 |

| Books (Valid N = 109) | 45.9% | 10.1% | 44.0% | 3.00 |

| Electronic journals (Valid N = 107) | 67.3% | 15.0% | 17.7% | 2.00 |

| Printed journals (Valid N = 110) | 60.0% | 16.4% | 23.6% | 2.00 |

| Mass media (television, newspapers etc.) (Valid N = 111) | 51.4% | 20.7% | 27.9% | 2.00 |

| Friends (Valid N = 112) | 41.1% | 22.3% | 36.6% | 3.00 |

| Colleagues (Valid N = 112) | 53.6% | 17.9% | 28.5% | 2.00 |

| Family (Valid N = 110) | 33.6% | 15.5% | 50.9% | 4.00 |

Table 5 provides the survey results for the importance of the different information resources in making medical decisions. The results indicate that medical staff (86.1%); family (30.6%), books (28.6%) and the Internet (56.2%) influence parents' clinical decisions.

| Information sources (questionnaire section 3b) | Level of importance in decision-making | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1 & 2) | Medium (3) | High (4 & 5) | Median value | |

| Medical staff (e.g. doctors, nurses)(Valid N = 86) | 5.8% | 8.1% | 86.1% | 5.00 |

| Internet (general search engines) (Valid N = 80) | 52.5% | 25.0% | 22.5% | 2.00 |

| Medical portals (Valid N = 79) | 63.3% | 16.5% | 20.2% | 2.00 |

| Books (Valid N = 84) | 57.1% | 14.3% | 28.6% | 2.00 |

| Electronic journals (Valid N = 81) | 68.2% | 15.3% | 16.5% | 1.00 |

| Printed journals (Valid N = 85) | 68.2% | 15.3% | 16.5% | 2.00 |

| Mass media (television, newspapers etc.) (Valid N = 82) | 70.7% | 13.4% | 15.9% | 2.00 |

| Friends (Valid N = 84) | 61.9% | 23.8% | 14.3% | 2.00 |

| Colleagues (Valid N = 81) | 67.9% | 18.5% | 13.6% | 2.00 |

| Family (Valid N = 85) | 50.6% | 18.8% | 30.6% | 2.00 |

The Mann-Whitney U test identified differences among acute and non-acute health condition groups in the importance given to family (U = 698, p =0.041, with mean ranks 43.36 and 27.38, respectively). The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed that when it comes to medical decisions, parents with a university education value the Internet (H(2)=10.747, p=0.05 with mean rank values of 33.78 for high-school level, 33.57 for higher technical level, and 52.00 university level), medical portals (H(2)=9.777, p=0.008 with mean rank values of 32.67, 35.02 and 51.36 respectively) and colleagues (H(2)=6.097, p=0.047 with mean rank values of 34.77, 37.46 and 49.45 respectively) more than the other groups.

Obstacles to information seeking

The survey results for the limitations/obstacles met by the parents during health information seeking are presented in Table 6. The major concerns of the parents that took part in the survey were the unreliability of health information on the Internet (35.3%), the infrequent visits to the doctor (31.4%), the vast amount of information (33.0%), and the lack of time with the doctor to ask all the questions required (31.2%).

The Mann-Whitney U test identified differences among children having acute or non acute medical conditions in the importance given to the intervening variable "infrequent visits to the doctor" (U = 575, p =0.014 the mean ranks were 45.67 and 62.00, respectively). Moreover, differences were identified for the parents of children of different sex for the "infrequent visits to the doctor" (U=980.00, p=0.13 with mean rank values 59.39 and 44.80 for parents with boys and girls, respectively).

| Barriers/obstacles (questionnaire section 4) | Level of importance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1 & 2) | Medium (3) | High (4 & 5) | Median value | |

| Lack of time with the doctor (Valid N = 109) | 56.0% | 12.8% | 31.2% | 2.00 |

| Infrequent visits to the doctor (Valid N = 108) | 41.7% | 26.9% | 31.4% | 3.00 |

| Lack of time for seeking information on the Internet (Valid N = 103) | 72.8% | 16.5% | 10.7% | 2.00 |

| Lack of organised information resources (Valid N = 97) | 56.7% | 18.6% | 24.7% | 2.00 |

| Lack of computer skills (Valid N = 103) | 80.6% | 11.7% | 7.7% | 1.00 |

| Information in a foreign language (Valid N = 101) | 62.4% | 9.9% | 27.7% | 2.00 |

| Vast amount of information (Valid N = 100) | 45.0% | 22.0% | 33.0% | 3.00 |

| Unreliable information on the Internet (Valid N = 102) | 39.2% | 25.5% | 35.3% | 3.00 |

The impact of information on the relationship between parents and their doctors

The results for the impact of information on the parent-paediatrician relationship are depicted in Table 7. Although parents indicated that the use of the Internet has not reduced their need to contact/visit their doctor/medical practice, the survey results demonstrate that they have an expectation that the doctor should provide suitable Internet health information resources (60.1%) for them. Parents also considered the retrieval of information from the Internet before their consultation with the doctor important (50.0%).

Statistically significant differences were identified using the Mann-Whitney U test between men and women for the level of importance assigned to discussing the information obtained from the Internet with the doctor (U=672.500, p=0.038 with mean rank values of 41.24 and 55.70, respectively). Kruskal-Wallis test identified education differences with those of higher educational level considering Internet health information seeking before doctor's visit more important (H(2)=7.346, p=0.025 with mean rank values of 44.08 for high-school level, 54.86 for higher technical level, and 62.54 for university level).

| Information impact on patient-doctor relationship (questionnaire section 5) | Level of agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1 & 2) | Medium (3) | High (4 & 5) | Median value | |

| Doctors should inform patients about suitable Internet health information resources (Valid N = 113) | 20.4% | 19.5% | 60.1% | 4.00 |

| Doctors should discuss and verify the integrity of information parents have retrieved from the Internet (Valid N = 109) | 69.7% | 11.9% | 18.4% | 2.00 |

| Internet health information seeking before doctor's visit (Valid N = 108) | 33.3% | 16.7% | 50.0% | 4.00 |

| The use of the Internet has reduced parents' need to contact or visit their doctor or medical practice (Valid N = 109) | 86.2% | 8.3% | 5.5% | 1.00 |

Discussion: the central role of information literacy for a parent and paediatrician participatory health care setting

Our survey of health information-seeking behaviour of parents of paediatric patients found that parents needed to be more informed and to know more to cope better with their child's medical condition. Using Internet information influenced parents' medical decisions and reduced their anxiety. Previous research has found that using information deriving from the Internet can lead to more informed patients, improved health results (Wald et al. 2007) and a clearer understanding of a medical condition (Berg 2005; McMullan 2006). However, our research demonstrated that parents, as surrogate information seekers for their children, struggled to find valid and authoritative information on the Internet experiencing a number of barriers, such as the lack of organised information resources, the unreliability and the volume of Internet information available. It seems that for the moment search engines such as Google may not be the answer to the role-shaping question of, 'Who knows what is right for my child's health and welfare?' Parents have responsibility for their children's health and they ultimately rely on doctors for the accurate interpretation of online information as well as for evidence-based medical advice.

Shared decision-making in health

Our research indicates that parents expect to be able to discuss information retrieved previously from the Internet with their doctor and thus engage in a two-way exchange of information. Evidence from medical research emphasises the role of informed participation of patients in clinical shared decision making. Shared decision making has been described as a process by which "mostly physicians, but also nurses and other allied health professions and patients converse about various options and preferences, reaching a decision by consensus" (O'Grady and Jadad 2010). It is therefore a process which requires educating each patient, understanding their circumstances and needs that are associated with their personal health, and presenting choices that meet these needs in such a manner that enables patients to select preferred options (President's Commission... 1982). In both of these definitions there is emphasis on patients communicating needs and preferences and medical professionals offering available options which can only be possible by means of "a non-hurried conversation...willing to listen and respect each other's views, values, and preferences" (O'Grady and Jadad 2010). However, paradoxically, in most consultations with doctors, patients have limited time to discuss or clarify information in any depth or consider possible treatments and outcomes in detail. In the case of parents, our research findings demonstrated that lack of time during a visit to the doctor and the infrequency of visits to the doctor were perceived as important barriers in this communication. Lack of time with the doctor was particularly emphasised as a barrier by parents of older children (7-13 years old) while the infrequency of visits was more prominent in parents of children with non-acute health conditions who had information needs related to long term prognosis issues.

Secondly, shared decision making has been characterised as 'essentially a relationship-centred', 'interdependent' process, with implies a joint decision made by the practitioner and the patient as they influence each other(Legare et al. 2012: 1311), in other words 'the expertise of both the doctor and the patient are recognised and seen to equally contribute to the consultation' (Melbourne et al. 2011: 55). Shared decision making emphasises an approach by which patients' perspectives are considered essential, are reviewed and valued and preferences are elicited (Elwyn et al. 1999). In this process patients are therefore considered to have developed a previousi views and opinions, for example about their medical condition and possible treatment preferences and their exposure to additional evidence given briefly at the practitioners' office may verify, alter or completely change them.

Parents develop views and preferences through exposure to a variety of different sources of health evidence, which include formal and informal, external and internal sources (Kempe et al.1999). For example, they weigh their personal knowledge and evidence derived from daily interactions with their child (personal context) against the advice and anecdotal stories of their closed family environment, their colleagues and friends (informal external/internal context), the Internet and other media (which direct them to a mixture of external formal and informal evidence). In turn, medical professionals rely on their medical experience and personal judgement, on trusted medical sources, other colleagues and the personal accounts, narratives, or medical records of patients. Shared decision making is therefore enabled via a critical information exchange process, which calls for a complex interplay between different layers of formal and informal evidence. Our research showed that parents utilised different sources depending on their information needs which were linked to the type of the health condition of their child. For example, parents of children with acute health conditions searched more for parental issues such as child development and nutrition and utilised more family and friends as information sources.

However, as a sense-making, dialectic exchange of information and a process that relies on existing knowledge structures of both parties, shared decision making requires a number of essential conditions and individual competencies. For example, it requires that parents, to maximise their effective inclusion in shared decision making, should be able to independently interrogate a range of formal and informal sources for their different information needs, and critically evaluate them, filter misinformation, carefully select good quality evidence and only communicate information that is worth further discussion, verification or clarification by the doctor in a timely manner. The results of our research demonstrated that the most frequently used information sources for parents were medical staff, Internet/search engines and members of their family. Other information sources such as electronic and printed journals were not considered equally significant. In addition, parents engaged less in previous health information seeking and their exposure to increasingly available medical information did not reduce the time they required with the doctor or their need to visit their doctor more frequently. More importantly, when this result was examined closely, it was found that parents with higher educational qualifications (post high school/technical; university or higher) engaged in more Internet health information seeking before their visit to the doctor and used Internet general search engines and medical portals more frequently than those with lower educational qualifications who, instead, preferred their family as an information resource. Consequently, some parents arrived less prepared or equipped than others to be fully involved into shared decision making.

A common information literacy space

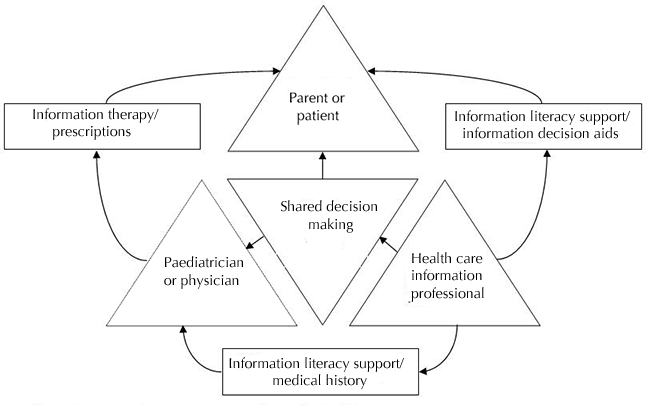

The development of information literacy is a crucial matter for considering the who and how of participation in the clinical decision making process. Information literacy includes an appreciation of the need for information, the ability to locate, evaluate and organise that information as well as the effective use of information to solve problems, make decisions, create new knowledge and supply information to others (Bruce 1998, 1999; Kirton and Braham 2005). It also extends to synthesising, extrapolating, presenting and communicating information in the most effective way (Bruce and Candy, 2000). Figure 1 provides a representation of a common information literacy space which would enable patients and parents and doctors and paediatricians to smoothly shift to a more participatory clinical decision making setting. This shift is being experienced in a number of ways that demonstrate variant levels of collaboration between health professionals and patients and parents, moving away from an expert disposition which creates a wider distance between patient and health professional to a more patient-focused exchange and two-way communication that involves analysis of that information and prescribing information.

This process also highlights the key role of the health information professional as a catalyst in the development of the information literacy of both parties and therefore as an indirect actor in the process of shared decision making. Both the patient or parent and the physician or paediatrician should overcome information barriers when seeking information from various sources to reduce uncertainty about options and preferred outcomes and reach mutual agreement on the best course of action. Information literacy is designed to provide the necessary common information behavioural framework for both the patient and the physician, to interact in such a way that shared clinical decision making can be realised.

Health information professionals have an important involvement in the provision of patient-based information services, such as the development of organised evidence-based health information resources and information decision aids which can be used by parents as information validation channels. For example, information decision aids based on research evidence are designed to inform patients and more importantly to help them think about what the different options might mean for them to reach an informed preference or decision. These aids can take a variety of forms, spanning everything from simple one-page sheets outlining the choices to more detailed leaflets, computer programmes, DVDs or interactive websites that include filmed interviews with patients and professionals, enabling the viewer to delve into as much or as little detail as they wish. These can be reviewed and absorbed by parents at home, before visitation to enable parents to discuss in a more informed manner their preferences during consultation and therefore to participate more fully in decisions on how to treat or manage the medical condition of their children.

However, as we have elaborated, shared decision making goes beyond the simple exchange of evidence-based information on symptoms, diagnosis, and therapy options and preferences and requires the timely prescription of evidence-based health information to meet individuals' specific needs (a process which is known as information therapy). It also requires 'a consulting style that is curious, supportive and non-judgmental' including, among others, 'information sharing', 'communication and managing uncertainty' and skills in 'summarizing, formulating and documenting the clinical decision' (Coulter and Collins 2011: 25)

Our study found that parents expected paediatricians to act as information verifiers, offering tailored information prescriptions of credible information resources (D'Alessandro et. al. 2004). This personalised information support requires a comprehensive understanding of parents' specific information needs within their situational context, their levels of understanding of their condition and the stage of information seeking in which they are situated at the time of the consultation. For example, depending on their stage in the information seeking process, parents may require less basic information and more specialised guidance. They may also require different levels of support to overcome uncertainty. For instance, we demonstrated how parents of children with non-acute health conditions searched more frequently for information on long term prognosis, an information need which may involve a higher level of uncertainty and anxiety.

Doctors should therefore appreciate the impact of different affective conditions patients go through in the process of information seeking such as increased uncertainty or even information avoidance (the tendency to ignore or avoid threatening or confronting information) (Case et al. 2005), which may create additional barriers in the process of shared decision making. Affective and cognitive conditions change during the process of information seeking as information seekers' knowledge structures are enriched and certainty levels increase/decrease with exposure to new information. For instance, parents may start with limited knowledge and understanding of their child's medical condition/problem and increased uncertainty when they first search for information which may later decrease as they collect more information. On the other hand, after having established basic understanding, exposure to different and often contradictory sources of evidence may result in frustration, confusion and doubt (Kuhlthau 2004) which can have a direct impact on their relevance judgments and how they react to the information offered in consultations. In the case of parents these negative affective situations and cognitive doubt may be increased by their extra anxiety and added responsibility they carry through their role as decision makers for their children.

For example, our study found that parents who visit the health practice for the first time use the Internet more frequently to minimise anxiety levels than parents who visit it for the second time. However, it was also very interesting to observe that Internet use for this purpose increased again after multiple visits to the health practice, possibly also indicating increased levels of anxiety after being exposed to additional or conflicting information. This is also supported by the findings which indicate that parents who visited the medical practice for the second time had more frequent information needs for finding a health care provider and potential diagnoses. According to Kuhlthau, in the initial stages of the information seeking process the uncertainty that is initially experienced is often replaced by a brief sense of optimism but as more inconsistent and incompatible information is encountered a sense of uncertainty, confusion, and doubt increase and result in reduced confidence (Kuhlthau 2004). This may indicate a zone of proximal intervention where the information seeker requires external help (e.g. from an intermediary) in the form of information literacy support or/and information decision aids to overcome this anxiety.

In our study, parents also identified infrequent visits to their paediatrician as a barrier in seeking health related information which, combined with lack of time, can have further implications for shared decision making. Using available time effectively in follow up consultations requires a good understanding of earlier information interactions that have taken place. These interactions may be recorded as interpersonal 'information anamneses/recollections' and combined with both actors' complex information sources/networks and information seeking behaviour. Preserving and recollecting information for the interactions between the patients (and their parents) and physicians may require additional support by health care information professionals to gradually employ a number of tools and techniques to record information-sharing and deliberation about options. Information professionals may also help parents increase their awareness of information services offered through online portals such as http://www.healthtalkonline.org and http://www.patientslikeme.com where they can not only find reliable health information, treatment options and the experiences of other parents but also record and share their own stories related to a specific health condition. This supportive role may be a new responsibility for health care information professionals within the health care system, to reduce the overall clinical consultation time and improve the quality of decisions made and therefore clinical outcomes.

Information literacy framework for health shared decision making

The process of shared decision making requires a new set of skills which points to a more collaborative relationship and effective dialogue between patients, doctors and health care information professionals, putting emphasis not only simply on finding and evaluating information but also on effectively communicating that information. Both parents and paediatricians may benefit from the additional support and expertise of health care information professionals to gradually employ a number of tools and techniques to support the effective communication and exchange of information for shared decision making. By helping parents and paediatricians develop their information literacy competencies holistically (e.g. understanding information needs, finding, evaluating, using and communicating information) health care information professionals can play a key role in engaging both actors in the process of shared decision making.

The conceptual framework in Figure 1 embodies a set of hypotheses about participatory health care which are testable and provide a source of hypotheses and a useful research framework for the investigation of health information literacy enablers in the context of participatory health decision making. The framework is a rather simple and implicit version and more elements need to be added for specific settings. However, the very fact that it is implicit stimulates further research about the specific information seeking motives, sources of information and barriers encountered when examining decisions about whether to undergo a screening or diagnostic test, undertake a medical or surgical procedure, participate in a self-management education or a psychological intervention programme, take medication or attempt a lifestyle change.

Conclusions

The results of this research study demonstrate that available information resources are not the only key to the effective exchange of 'expertise' and for the information sharing and participatory process to work. The development of health information literacy, a cluster of interconnected, transferable competencies, is essential in the health professional-patient dyad of medical shared decision making. The development of information literacy as a process of dialogue between parents and paediatricians may to lead to the utilisation of fewer medical resources at the clinic, an improved capacity for making informed decisions and an increased, equal involvement in shared decision making.

Health professionals should also have the ability to search for, evaluate, consolidate, simplify and effectively communicate health information to patients in a way that relates to their needs. They should be in the position to verify the patient's level of understanding and assess their degree of uncertainty (Legare et al. 2012). According to our research, parents turned to the Internet to reduce their anxiety levels. By understanding the process of information seeking and appreciating the role of information literacy both in parents' everyday lives and their own professional contexts, medical professionals can enrich their clinical support by recognising zones of proximal intervention for parents, providing guidance and useful direction when it is required (Kuhlthau 2004)

Despite the increasing emphasis on the value of the participatory approach in clinical decision making, it remains unclear whether both parents and medical professionals are equipped with the necessary competencies that are required in this process. Future research should therefore establish more clearly the relationship between information (information literacy, and various information decision aids, information prescriptions, information therapy etc.), communication and shared decision making. Health information professionals may have a key role to play in fostering and elevating both health professionals' and parents' information literacy and communication skills and potentially becoming a direct player in maximising opportunities for improved health outcomes via shared decision making.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to P. Nikolaidou-Karpathiou, Professor of Pediatrics, Director of Department of Pediatrics, Attikon University Hospital and the members of scientific committee of Attikon Hospital. We are also particularly grateful to T.Karpathios, Professor of Pediatrics, A.Konstantopoulos, Professor of Pediatrics, President of Hellenic Paediatric Society, President of European Paediatric Association, and D.Konstantinou, Pediatrician-Neonatologist, Director of NICU IASO for participating in the questionnaire development.

About the authors

Petros A. Kostagiolas is a lecturer in the Department of Archive and Library Science, Ionian University, Greece. His research interests include the theory and practice of intellectual capital management, quality management, as well as information services and behaviour for participatory health care settings. He holds a Ph.D. in the field of quality and reliability management from the University of Birmingham, U.K. and he can be contacted at: pkostagiolas@ionio.gr.

Konstantina Martzoukou is a Lecturer in the Department of Information Management, The Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland. Her research interests include information seeking behaviour, information literacy and digital literacy. She holds a Ph.D in the area of Web information seeking. She can be contacted at: k.martzoukou@rgu.ac.uk

Georgantzi G. Georgia is a resident doctor in paediatric Department of Attikon University Hospital. She received her Medical Doctor degree from the University of Patras and she holds a M.Sc. degree in health care Management from the Hellenic Open University, Greece. She can be contacted at: g_ergina@hotmail.com

Dimitris Niakas is Associate Professor at Hellenic Open University and Head of the Postgraduate MSc Program in Health Services Management. He studied Economics (BSc), Health Services Administration (Dipl), Health Planning and Financing (MSc) and Health Economics and Policy (PhD). He can be contacted at: niakas@eap.gr