Social capital and library and information science research: definitional chaos or coherent research enterprise?

Catherine A. Johnson

Faculty of Information & Media Studies, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada

Introduction

Social capital has become one of the most dynamic areas of research in the social sciences in recent years. An indication of the growth in interest in this research area is evident from a search in Web of Science, which revealed that the number of papers mentioning social capital in either the title or topic increased from fifteen papers in 1993 to 943 papers in 2014 for an overall total of 9,512 papers during that period. According to Woolcock (2010, p. 470), it can now safely be said that social capital is in the mainstream of the academic research enterprise. Another indication of the popularity of the concept is the plethora of definitions that have also arisen. One researcher has estimated that over 1,200 definitions of social capital have appeared over the last two decades (Dale and Onyx, 2005, p. 15). This has resulted in one of the main criticisms of social capital: its 'definitional chaos' (Fine, 2010, p. 5) and lack of a consistent conceptual framework and, therefore, the difficulty of developing a rigorous theory of social capital. Nevertheless the concept has proven to be popular over a broad cross section of academic disciplines including library and information science.

Use of the concept of social capital in library and information science research surfaced in 1999 with a paper (Attewell and Battel, 1999) that studied the effect of home computers on educational attainment using social capital as a control variable. A second paper appeared in 2000 when the University of Technology, Sydney (2000) published a report of a study conducted amongst Australian public libraries, which used the concept of social capital to understand how libraries help to create trust in communities. The real impetus for interest in studying the intersection of libraries and social capital, however, appears to have been Robert Putnam's talk to the American Library Association meeting in 2002 and the inclusion of a chapter in his book, Better together: restoring the American community, (2003) called Branch libraries: the heartbeat of the community, which focused on how social capital was generated by a neighbourhood branch library in Chicago. A search of the term social capital in the title, abstract or keywords in the database, Library, information science and technology abstracts found that since 1998 there have been over 200 academic journal papers either reporting on studies that framed their research using social capital theory or that conceptualised how the theory of social capital could be used in library and information research. This paper will examine those papers to determine whether there has been consistency in how social capital has been conceptualised and defined in library and information research. It will begin with a review of the origins of the concept of social capital.

Social capital and social network analysis

While the community focus of social capital has certainly eclipsed other research efforts, an understanding of social capital's origins in structural sociology and, in particular, social network theory, helps clarify the importance of relationships or ties in the creation of social capital. The main difference between social network theorists and the social capital theorists who focus on the societal benefits of social capital, is that the former take as their unit of investigation the relationships between individuals, while the latter focus on the social capital of the community as a whole. Social network analysts are interested in the influence of the social structure on individuals; that is, the location of individuals in the structure and how the configuration and characteristics of ties that make up the social network affect their access to resources (Portes, 2000). Burt (1992, 1997) showed the importance of social structure through his identification of structural holes, which are gaps between two or more networks that people could fill and, thereby, occupy a brokerage position between the networks. The broker would not only link the two networks but could also control the information that flowed between the networks. According to Burt, '[t]he structural hole argument defines social capital in terms of the information and control advantages of being the broker in relations between people otherwise disconnected in social structure; (Burt, 1997, p. 340).

Granovetter's (1973) concept of the strength of weak ties, explains the benefits derived from different types of relationships between individuals. He explains that when people are looking for information about new jobs, the most beneficial ties are those with acquaintances rather than close friends. The advantage of weak ties is that they link people into networks containing new information that they are unable to attain from close ties. Having weak ties in your network, therefore, could be the social capital that gives you an advantage over others. In both Burt's and Granovetter's conceptions of the value of structural location and quality of ties, the underlying assumption is that these ties are often acquired instrumentally.

Strong ties that are characterised by trust and reciprocity, and weak ties that link into new networks relate to the bonding and bridging concepts that make up essential components of the theory of social capital. While bridging social capital is usually associated with individual level social capital, bonding social capital is more associated with the community or collective view of social capital. Bonding social capital is based on the idea that large, dense networks and people with common values can be resourceful to one another, working together to achieve mutually beneficial ends. It is more closed in nature, and contained within the stronger relationships among members of a group. Bridging social capital comprises the weak ties that link into different social networks and thus provide greater access to more varied and often higher quality resources.

These two different effects of social capital, the collective and individual benefits of social relationships, and two different types of social capital, bridging and bonding ties, represent the major strains of social capital research. In the next section I will examine papers published in library and information science journals to determine how these concepts are incorporated into library and information science research.

Method

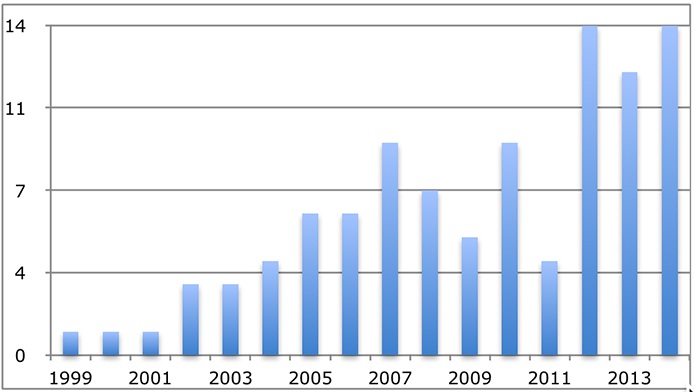

To draw conclusions as to how social capital theory is utilised in library and information research, I searched the databases referred to earlier. I searched for the term social capital in the title, abstract, subject or author supplied keywords for both databases up to December 2014. I retrieved 201 records of papers published in English in peer-reviewed journals. To further refine the search I included only papers that had a specific library and information science orientation and focused on social capital as a theoretical framework. The journal titles were also checked against a list of core journals within library and information science that were compiled from expert opinion surveys, acceptance and circulation rates, impact factors, and whether they contained papers by local library and information science faculty (Nixon, 2014). However, I did not exclude papers from journals not on this list as that would have omitted papers written by, or of specific interest to, many library and information science faculty and researchers. For instance, the papers by Gong, Japzon and Chen (2008) and Svendson (2013) although not published in journals included in the core list of library and information science journals, met the other criteria and had a strong library and information science focus (both were about libraries). This narrowed the list to ninety-nine papers, of which seventy-nine were empirical studies and twenty consisted of conceptual papers, editorials, or reviews of social capital research. All of the papers were read to ensure that social capital was the primary focus of the paper, included a definition of social capital, and for the empirical studies included a literature review and methodology sections. While library and information science researchers do not restrict themselves to journals accessed through databases searched, I believe the papers retrieved provide a representative sample of the type and scope of library and information science research using social capital as a conceptual framework. The dates in which these papers appeared are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Number of library and information science papers published 1999 to 2014 that focus on social capital research (total=99)

As is apparent from the above chart, the number of library and information science papers focusing on social capital research has risen steadily since the first paper appeared in 1999, with the years 2012 to 2014 showing an increasing number of publications than previous years. This suggests that social capital research continues to be of growing interest to library and information science researchers. Some journals showed a greater propensity to publish social capital papers than others: Library & Information Science Research (11), Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology (7), Behaviour & Information Technology (7), and The Information Society (6) were prominent disseminators of social capital research.

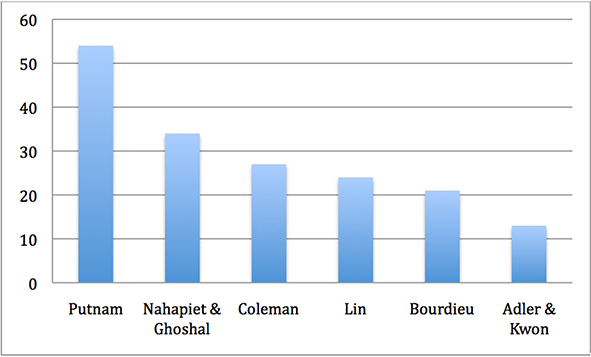

To track how social capital is conceptualised in library and information science research, as either a collective or individual resource, or a combination of both, it is necessary to examine the definitions of social capital used by the researchers and the scholars they cite. Figure 2 presents the number of times social capital scholars were cited in the papers included in this study.

Figure 2: Top cited social capital scholars in library and information science research

The most commonly cited scholar was Robert Putnam who was cited in fifty-four of the papers. His book, Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community (Putnam, 2000), is also one of the most highly cited works, having been cited over 32,000 times according to Google Scholar. Coleman, with twenty-seven citations, is usually included along with Putnam in the literature reviews. A typical definition of social capital in the library and information science papers that cite Putnam explains what social capital is as well as its benefits: social capital 'refers to networks, norms, trust and mutual understanding that bind together the members of human networks and communities and enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives' (Widén-Wulff and Ginman, 2004, p. 449). Most papers that focus on Putnam's conceptualisation emphasise the societal benefits of social capital: 'Social capital is associated with multiple societal developments, democracy, economic development, government efficiency, community development, schooling, individual health and well-being, and with combatting crime, drug abuse, and teenage pregnancies' (Varheim, Steinmo and Ide, 2008, p. 878). Another example is from Cao, Lu, Dong and Tang who combine definitions from Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) and Putnam (2000) in their definition of social capital:

Social capital is a resource that helps sustain a community... social capital encourages collaboration and cooperation between members of groups for their mutual benefit. Thus, social capital theory can capture the essential content of information exchange and social collaboration (Cao, Lu, Dong and Tang, 2013, p. 1672).

Nahapiet and Ghoshal's (1998) paper is one of the most highly cited in social capital research (11,106 citations according to Google Scholar's database) and was also highly cited by papers in this study (by thirty-four out of ninety-nine papers). Although mostly of interest to management scholars, library and information science researchers also find Nahapiet and Ghoshal's interpretation of social capital to be particularly helpful in understanding information sharing within or among organizations. Aware of different scholars' focus on one or the other of social capital's dimensions (bonding or bridging social capital), Nahapiet and Ghoshal insist that social capital is not a one-dimensional concept. Incorporated in their definition of social capital is the idea of resources in social networks available to individuals as well as the close, trust-building ties that lead to information sharing. They define social capital as 'the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or social unit' (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998, p. 243). They identify three dimensions of social capital: structural, relational and cognitive. Structural social capital refers to the overall pattern of connections between actors: density, connectivity and hierarchy.

Granovetter (1973) and Burt (1992) and other structural sociologists are referenced in relation to structural social capital. Relational social capital is conceived as assets created and leveraged through relationships. These assets are behavioural rather than structural, and consist of trust, norms and sanctions, obligations and expectations, identity and identification (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998, p. 244). The major scholars they cite associated with these concepts include Fukuyama (1995), Putnam (1993, 1995), Bourdieu (1986), Coleman (1990), and Burt (1992). The cognitive dimension of social capital is their unique contribution to the development of social capital theory and not often included in the literature outside of management studies. Cognitive resources refer to 'resources providing shared representations, interpretations and systems of meaning among parties' (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998, p. 244). This concept is important to the authors because it relates to how social capital leads to the creation of intellectual capital, an outcome of sharing knowledge and information.

Closely connected to Nahapiet and Ghoshal's conceptualisation is Adler and Kwon's conceptual model (2002), is cited thirteen times by papers in this study, usually along with Nahapiet and Ghoshal. Adler and Kwon call social capital an umbrella concept 'that attracts researchers from heterogeneous theoretical perspectives' (2002, p. 18). Their definition draws together both conceptions of social capital and state that how social capital is defined and what conceptions are emphasised vary depending on whether the focus is on the substance, sources or effects of social capital and whether the units of study include the relations between actors (bridging ties) or the structure of relations within a collectivity (bonding ties) or both (Adler and Kwon, 2002, p. 19). Their definition encompasses internal and external ties and allows social capital to be attributed to both individual and collective actors: 'Social capital is the goodwill available to individuals or groups. Its source lies in the structure and content of the actor's social relations. Its effects flow from the information, influence, and solidarity it makes available to the actor' (Adler and Kwon, 2002, p. 23). Their social capital framework comprises three dimensions or aspects: opportunity, motivation and ability, which map well on to Nahapiet and Ghoshal's dimensions. Opportunity refers to the structural aspects of social capital: the types of ties, frequency of interaction and number of ties to which individuals are connected. Motivation is similar to Nahapiet and Ghoshal's relational dimension of social capital: the norms, trust and shared values among ties that can either remain dormant, but can also be instrumentally accessed to achieve certain ends. Ability is similar to Nahapiet and Goshal's idea of the cognitive dimension or shared beliefs among members of a collectivity. As with Nahapiet and Goshal, this third dimension is not well-defined and difficult to distinguish from the structural and relational forms of social capital. Ability, defined as the 'competencies and resources at the nodes of the network' (Adler and Kwon, 2002, p. 26), can also be conceived of as the quality of the resources in the network, which, according to Lin (2001) and other social network theorists, is the core concept within the theory of social capital.

With twenty-four citations in the sample as well as 6,310 citations according to Google Scholar, Nan Lin is also a major scholar in social capital research. Lin's social capital theory (2001) evolved directly out of social network theory and social resources theory that he developed in the 1980s (Lin and Dumin, 1986). Lin builds on Burt's (1992) and Granovetter's (1973) concepts of structural location and promulgates a social capital theory that emphasises the advantages that are gained from the quality of an individual's social network. Lin's network theory of social capital explains how social capital arises out of the network structure and provides us with a greater understanding of the causal direction of social capital (Lin, 2001; Lin, Cook and Burt, 2001; Lin and Erickson, 2008). Lin's definition is close to Bourdieu's class-based analysis, as he claims that the quality of social capital increases as one moves into higher levels of the social structure. Lin defines social capital as 'resources embedded in social networks accessed and used by actors for actions' (Lin, 2001, p. 25). He regards the accumulation of weak (or bridging) ties as a deliberate strategy to access higher quality resources that are often available from people in more distant networks. In addition, people who have a variety of ties linked to different skills and assets (diversity) tend to do better than those whose networks are largely made up of close friends and family (Erickson, 2003).

Lin measures social capital using a position generator which calculates social capital based on the quality of ties to which an individual has access. The position generator consists of a list of occupations or other structural positions that represent hierarchical positions in the social structure (Lin, 2001, p. 88). Research participants are asked to indicate whether they know anyone in each of these occupations whose status is determined by empirically derived prestige scores. The quality of social capital is based on a combination of reach, the highest-ranking occupation to which an individual has access; diversity, the number of different occupations to which an individual has access; and extensity, the difference between the highest and lowest positions accessed. Despite Lin's focus on instrumental ties, he also acknowledges the importance of expressive forms of social capital, which are the social and emotional support derived from close friends and family. Nevertheless, these expressive forms of social capital are rarely examined in studies conducted by Lin.

Pierre Bourdieu, with twenty-one citations by authors in this study as well as nearly 22,000 citations according to Google Scholar for his paper The forms of capital (1986), was most often cited in the literature reviews when explaining the origins of the concept of social capital. but his ideas were usually not explicated beyond quoting his definition of social capital (see for example, Elbeshausen, 2004; Liao, 2012; and Oztok, 2013). However, in a few cases, Bourdieu's conceptualisation of social capital was the focus of the study. For instance, concerned with the expansion of the concept of social capital beyond its original scope, Yuan, Gay and Hembrooke (2006) limited their study to Bourdieu's definition: 'properties of a network structure that members of the network can access and activate in order to achieve their goals' (p. 27). Other scholars focused on Bourdieu's class-based analysis. Lin and Chen's study (2012) of the differential power among taggers was based on Bourdieu's conception that possession of cultural and social capital determines one's social status and influence (p. 541). Moniarou-Papconstantinou and Tsatsaroni's study (2012) of the educational trajectories of library and information science students focused on Bourdieu's concept of habitus which 'provides the means for understanding how differences of social, cultural and economic character may influence the way young adults perceive the available opportunities, and lead them to make appropriate choices' (p. 240). Since Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) also focus on Bourdieu's concept of network assets, several of the knowledge management studies also referenced Bourdieu (Wickramasinghe and Weliwitigoda, 2011; Wu, Chang and Chen, 2008; Huvila, Holmberg, Ek and Widén-Wulff, 2010) when discussing the relational dimension of social capital.

Although both individual and collective returns should be considered in assessing social capital, many studies focused on either one or the other based on the context and motivation of the study. In the next section I will examine the library and information science literature on social capital to determine, among other things, whether studies incorporated both concepts of bonding and bridging ties, and whether one concept was used more frequently than the other.

Social capital and library and information science research

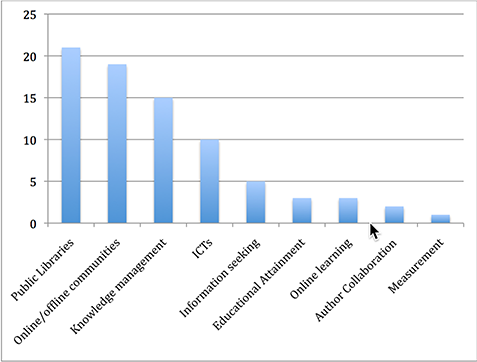

The concept of social capital fell under several areas of library and information science research: public libraries (27%), offline and online communities (24%), knowledge management (19%), information and communication technologies (use and impact on society) (13%), information seeking (6%), educational attainment (4%), online learning (4%), author collaboration (3%) and one paper focusing on measurement of social capital. The numbers of papers in each research area are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Library and information research areas using concepts of social capital (based on empirical research studies) (n=79)

Public libraries and social capital research

Twenty-one papers reporting on empirical research were published focusing on how public libraries help to create social capital, both in the communities in which the libraries are located as well as for individuals using the library. While much of the earlier studies came out of Australia, the most current research has come mainly from two sources: the Public Library – Arenas for Citisenship (PLACE) project in Norway, which has produced ten papers, and studies conducted by Catherine Johnson and Matthew Griffis in both the United States and Canada, which have produced six papers.

Because public libraries are community organizations, Putnam's community level social capital concept has most frequently been used to identify the links between public library use and the creation of social capital. In the PLACE studies, social capital is usually interpreted as the creation of generalised trust (Varheim 2009). Because of the high levels of immigration in Norway, the researchers were motivated to show how public libraries can help to integrate immigrant groups into Norwegian society. They focus mainly on Putnam's definition that comprises both bonding and bridging social capital:

In social-capital research, there are two forms of social capital: bonding social capital in the form of networks and thick confidence (particularised trust) between members of tight and highly-integrated groups; and bridging social capital in the form of networks and thin confidence (generalised trust) across primary belongings (Aabo and Audunson, 2012, p. 141).

They call this the societal perspective. They add another perspective, called the institutional perspective, which relates to the trust building 'effects of universalistic and impartial public institutions and democracies' (Varheim 2014, p. 259). The researchers demonstrate that libraries are useful in bringing disparate people together in a safe place where they have the opportunity to get to know one another, or at the least, observe each other, and therefore increase levels of trust among them. They developed two concepts related to bridging and bonding social capital that help to explain this process: low intensive and high intensive meeting places. Low intensive meeting places are places where people are exposed to 'other values and interests than those they adhere to themselves' (Aabo, Audunson and Varheim, 2010, p. 17). These places can be assumed to exist of potential, or latent, weak bridging ties. High intensive meeting places are just the opposite: they are places where people gather who generally share similar values, customs and world view, which are equivalent to bonding ties.

In attempting to understand where social capital comes from, the PLACE researchers hypothesise that the first step to creating trust (considered equivalent to social capital) was to reduce inequality. Because libraries are universalistic institutions, open to everyone and provide a standardised service, it is the ideal location in which to observe the micro-mechanisms that lead to greater trust (Audunson, Varheim, Aabo and Holm, 2007). It was expected that contact between new immigrants and longer term residents in libraries would result in the development of trust between them and thus a greater integration into the dominant society. Their studies, however, have had mixed results. Based on interviews and observations within the library, the researchers found that both high- and low-intensive meetings took place in the library (Audunson et al., 2007; Aabo and Audunson, 2012; Aabo et al., 2010) and that most of the interactions that took place within the library were between friends and family and thus equivalent to bonding social capital. A study (Audunson, Essmat and Aabo, 2011), which involved interviews with nine immigrant women, showed that these women, through their use of the library, established contacts with the majority population, and thus increased the feelings of trust towards them.

A similar study by Varheim, this time involving undocumented immigrants in Colorado, found that although trust in the library increased through attendance at library programmes, this trust did not extend beyond librarians and other library users. Nevertheless Varheim found that the initial mechanisms that generated trust and could lead to more trust in the general population were present in the library itself (a trusted institution) and the librarians and teachers who presented the programs (Varheim, 2014, p. 272). In these studies, bridging ties are not necessarily providing access to new resources, as in Lin's definition, but rather they are a possible entry into the dominant society through the development of trust. According to the authors, the formation of bridging ties, or generalised trust, is the first step towards the creation of strong, integrated communities.

Studies conducted by Johnson (2007, 2010, 2012), Johnson and Griffis (2009, 2014) and Griffis and Johnson (2014) looked at the effects of library use on both individual social capital and community social capital. These studies used both quantitative and qualitative research methods and combined Putnam's and Lin's approaches to provide a more holistic view of the value of libraries to both individuals and the community. Bonding social capital was measured using questionnaires developed from Putnam's Social Capital Community Benchmark surveys (SK 2006..., n.d.), which measured social capital based on levels of community involvement, civic engagement and trust. The questionnaires were administered to library users in both urban and rural libraries. The researchers found significant statistical associations between the frequency of library use and all three measures of social capital in urban libraries, but not rural libraries (Johnson 2010; Johnson and Griffis, 2009, 2014). The explanation given for this difference was that small town libraries were mostly frequented by middle class patrons who already had high levels of trust, while urban libraries had a higher proportion of poor patrons who benefited from the social and information resources available from the library (Johnson and Griffis, 2014, p. 187). Bridging social capital was measured using Lin's position generator (Lin, 2001). A negative associations was found between individual measurements of social capital and library use in urban areas, suggesting that people did not necessarily increase their level of social capital by using the library but rather an individuals' use of the library was a strategy to make up for their low levels of social capital.

Qualitative interviews also revealed the interactions that occurred in urban libraries that were predictive of increased social capital, such as greater access to information resources in the library as well as to resources existing outside the library, personal engagement between library users and staff such as keeping an eye on children left in the library on their own and offering special afterschool programs (Johnson, 2010; Johnson and Griffis, 2009; Griffis and Johnson, 2014). Griffis and Johnson (2014) also identified four major public library roles that would help increase social capital in rural communities, including: acting as both an information and a social hub for the community, helping to integrate newcomers into the community by hosting book clubs and children's programming, through the importance of the physical library itself which stands as an important source of community identity and, finally, by the library serving as one part of a larger network of community groups and organizations.

Social capital and online and offline communities

Community studies have proven to be a particularly strong area of research using the concept of social capital. Many of these studies extend from early community studies conducted by sociologist Barry Wellman and colleagues in the 1970s and beyond. In these studies Wellman showed that despite the fact that people were no longer closely connected within physically bounded communities, they were able to maintain strong interpersonal links through the use of technologies such as the telephone and the automobile (Wellman, 1979). With the appearance of the Internet, researchers wondered whether this newest technology would finally rend apart even these social connections as people spent more and more time online. Library and information science studies focused both on the effects of Internet use on offline relationships as well as the effect of a person's involvement in social media on individual social capital. One of the first papers to address this concern was Wellman, Quan-Haase, Witte and Hampton (2001), which situated its argument in reaction to Putnam's studies that found that American's social capital had been declining since the Second World War (Putnam, 2000l). Wellman et al. explained that Putnam may have been looking at outmoded ways of creating community. They suggest that new ways of creating community, through involvement in online communities, may in fact be replacing the social capital Putnam claims has been lost (Wellman, et al., 2001, p. 437). They describe three forms of social capital:Network capital: relations with friends, neighbors, relatives and workmates that provide companionship, emotional aid, goods and services, information, and a sense of belonging.

Participatory capital: Involvement in politics and voluntary organizations that affords opportunities for people to bond and create joint accomplishments.

Community commitment: the strong sense of community involvement that will mobilise their social capital more effectively. (Wellman et al., 2001, p. 437).

The first two relate to Putnam's work, while the third is derived from the authors' community studies. In all of these forms, however, the focus is on the strong, bonding ties that provide social and emotional support and lead to feelings of well-being and trust. The authors found that the Internet does not diminish social capital but is just another medium through which people can form and maintain relationships, supplementing social capital rather than diminishing it. However, they also speculate that increased involvement in Internet activity reduces individuals' sense of community online (Wellman et al., 2001, p. 451).

Building on this research, Ellison, Steinfield and Lampe (2007) studied users of Facebook to determine what connection there was between online and offline social capital. Previous research had found that relationships formed online would move offline and thus add to individuals' total bank of social capital (Wellman, Salaff, Dimitrova, Garton, Gulia and Haythornthwaite, 1996; Parks and Floyd, 1996). The study by Ellison et al. (2007) was conducted among undergraduate users of Facebook to determine to what extent social networking sites are used to create new friendships or maintain old ones using both the bonding and bridging concepts of social capital. They found that Internet-instigated relationships result both in the formation of weak ties, or links into new networks, while at the same time assisted in the maintenance of their close or bonding ties. Ahn (2012) drew on both bonding and bridging concepts to investigate the relationship between use of social networking sites, such as Facebook and MySpace, and the presence of social capital among teenagers. Ahn used the Internet social capital scales developed by Williams (2006) to measure the relationship between social capital and site use. Bonding social capital was measured by asking students about the existence (or lack thereof) of trusting relationships and people they can turn to for advice (Ahn, 2012, p. 102). Bridging social capital was measured by asking questions about whether interacting with people on Facebook led to the participants becoming interested in things that happen outside their town or in trying new things (Ahn, 2012, p. 102). She found that being a member of a social network site was associated with developing both bonding and bridging social capital, although the results were mixed. The importance of this research, Ahn states, is to indicate to parents and other caregivers that use of social networking sites does not necessarily have detrimental effects, such as cyber-bullying or time-wasting, but can lead to positive social interactions (Ahn, 2012, p. 107).

Recently Appel, et al. (2014), have highlighted problems with the Williams's scale used to measure social capital in online communities. By comparing the long established and tested network social capital measurement instruments, e.g., name generators (Burt, 1997), position generators (Lin, 2001) and resources generators (Gaag and Snijders, 2005), with Williams's scale (Williams, 2006) they found that there was no direct correlation between the findings of the two methods for measuring social capital (Appel et al.m 2014, p. 408). This illustrates the difficulty many have with social capital theory since one cannot be sure that the same indicators of social capital are being measured.

Another example that shows how community can be built through participation in online communities is a study of people suffering from motor neuron disease by Loane and D'Allessandro (2013). The study uses Lin's (2001) definition of both instrumental and expressive forms of social capital: resources embedded in networks accessed by actors for actions, with the resources including both information and social support (Loane and D'Allessandro, 2013, p. 168). The bonding aspect of online communities is the specific topic or interest around which the community is built, and the bridging aspect is the bringing together of 'geographically disparate individuals from a variety of racial and educational backgrounds' (p. 168). The methodology to determine the presence of social capital consisted of identifying instances in online conversations that include examples of trust building and generalised reciprocity. The members of the online community also benefited from the diversity of expertise present in the weak ties comprising the group that resulted in highly useful information flowing to its members. This is an excellent example of how both bonding ties (brought about by a shared common interest) and bridging ties (weak ties linking into different social networks) help to build a strong community around a common interest.

Social capital and knowledge management research

Nahapiet and Ghoshal's (1998) and Adler and Kwon's (2002) knowledge management papers prompted several information science researchers to look at the influence of social capital on knowledge or information sharing in organizations. A paper by Huysman and Wulf (2006) pointed out that formal tools to promote knowledge sharing that are decoupled from workers' social environment do not work well. Organizations should therefore recognise the important role played by social capital in encouraging employees to share information. Huysman and Wulf state that by 'scrutinizing communities' degree of social capital and by improving the level of social capital tools for knowledge sharing will likely be more in line with people's opportunities, motivation and ability to share knowledge' (p. 44).

Several other papers focused on how social capital: encourages knowledge sharing within organizations (Yang and Farn, 2009; Hau, Kim, Lee and Kim, 2013), enhances the careers of information technology professionals (Zhang and Jones, 2009), helps software developers employed in outsourced offshore software development (Wickramasinghe and Weliwitigoda, 2011), and impacts collaborative work projects (Bhandar, 2010). Each of these papers explained knowledge sharing in organizations based on the models introduced by either Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) or Adler and Kwon (2002). These organization studies provide the optimum situation where social capital provides benefits to both the organization (community-level social capital) and individuals, showing the possibility of combining these different dimensions of social capital into one coherent theory.

Social capital and information and communication technologies

The concept of social capital has also been used in studies examining the digital divide, the adoption of information and communication technologies by both individuals and communities, and community informatics. Early in the 2000s, Warschauer (2003) drew the link between social capital and the digital divide. He anticipated that both individual and collective levels of social capital would influence peoples' ability to adopt information technologies. He speculated that both trust (bonding ties) and weak links to knowledgeable people in community access centres were important in the willingness and ability of people to use these technologies (pp. 317-318). A study by K. Williams (2012) confirms the importance of bonding social capital in the use of information and communication technologies, indicated by levels of trust that built up between people that encouraged them to take up the new technologies. Drawing mainly on Lin's (2001) conception of social capital, Chen (2013) focused on individual-level social capital and the extent to which people get assistance from family and friends to solve technical problems. In many of these studies, it was found that both the bonding and bridging forms of social capital have an impact on individuals' acceptance of new information technologies.

Community informatics, or the relationship between information and communication technologies and community development, is interested in determining the impact of these technologies on communities as well as the motivation for people to take them up. Farooq, Ganoe, Xiao, Merkel, Rosson and Carroll (2007) examined how participatory design for a community Website drew on community social capital in the form of weak and strong ties with the right skills to develop the Website. Mignone and Henley (2009) presented five case studies examining the impact of the introduction of information and communication technologies on aboriginal Canadian communities. They found that investment in remote communities in the technologies can increase their bridging capabilities to other native communities as well as contacts with government and non government agencies. The sharing of information among different communities was thought also to enhance their ability to negotiate more favourable land claims. Similarly research by Hui, Wenjie and Shenglong (2013) used a case study methodology to examine the impact of such technologies on villages in the Tibetan region of China. They found that bridging social capital was evident in the financial, educational and human resources drawn upon to develop the project and make it useful for villagers, and that bonding social capital motivated people to make use of the technologies and thus reduce digital poverty.

Social capital and information seeking

Studies that focus on information seeking behaviour attempt to show the effect of an individual's level of social capital on their ability to find useful information. Johnson (2004, 2007) used a social capital framework to investigate the information seeking behaviour of urban Mongolians. Viewing social capital as resources embedded in networks accessed by individuals for their benefit, the study was based solely on Lin's definition of social capital. Members of individual social networks were elicited using name generators that identified both close and distant ties based on questions asking for names of people who provide certain levels of help. Lin's position generator (2001) was also used to determine the quality of resources in the network based on access to people located in a range of occupations. The study found that people with higher levels of social capital were more likely to find the best sources of information that addressed their problems (Johnson, 2007), and that they used their weak ties when using people as information sources (Johnson, 2004).

A study by Woudstra, van den Hoof and Schoute (2012) that focused on information seeking, used the model developed by Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) to determine how the choice of an information source was affected by its quality and accessibility. In this study scenarios were developed and presented to members of a business organization to indicate who they would approach for information. These elicited names of information sources as well as the effect of the quality and accessibility of the source on its selection. Quality was seen as having a stronger influence on choice of source than accessibility. As with Johnson's (2004) study, individuals were willing to go outside their zone of comfort (their close ties) to get the best quality information, thus challenging a common perception in library and information science literature that the choice of a person as an information source is usually a least effort option (Case, 2002, p. 142).

While these information behaviour studies showed the importance of weak or bridging ties in the search for information, other studies have found that bonding ties are also important for the acceptance of information. Veinot (2009, 2010) examined the networks of HIV/AIDS patients living in rural Canada to determine how they build information or help networks to help them cope with this serious illness. Through interviews with HIV/AIDS patients where she administered a name generator to elicit both past and current members of their networks Veinot was able to demonstrate the dynamic nature of social networks and the information seeking process. She found that the HIV/AIDS patients divested themselves of certain network members who were more judgmental of their situation, but added new ones consisting of close ties who would provide emotional support as well as new professional ties who would provide good quality information. As with the Loane and D'Alessandro (2013) study, identifying both bonding and bridging ties was important in understanding the full scope of how social capital benefits individuals.

Discussion

Despite Fine's (2010) claim of the 'definitional chaos' of the concept of social capital, most library and information science researchers have based their conceptualisations on the work of core social capital theorists such as, Bourdieu, Coleman, Putnam and Lin. Depending on the focus of their research they either look at social capital from a community perspective or from an individual perspective, and sometimes both. They often also include both bonding and bridging forms of social capital in their analysis. These two perspectives seem to be radically different ways of viewing social capital, with community level theorists emphasizing the trust that builds up through tight bonds of social interaction, and social network theorists focusing on the benefits to individuals of having high quality ties within their networks or weak ties that link to better resources. However, both these perspectives come down to a similar effect: the benefits of social relationships to individuals, communities, and firms.

Researchers interested in societal or community benefits of social capital, usually follow Putnam's approach, which measures social capital as the presence of trust and the shared norms and values of strong bonding ties. The Norwegian and Johnson and Griffis studies demonstrate that having a place that is open to all and where diverse members of society can gather has positive outcomes in building both awareness of different others in the community and, through their interactions, also build greater levels of trust. Lin's approach, which focuses on individual social capital, is well-suited to studies of information seeking, which capture the often deliberate attempt to acquire useful contacts. Nahapiet and Ghoshal's social capital model (1998) combines both perspectives: Putnam's conceptualisation of trust that leads to information sharing and Lin's social network approach that focuses on the social capital that exists in relationships, which when accessed, results in better outcomes for the organization.

Network analysts often criticise community level social capital theorists because of the difficulty in determining causal direction. Their argument is, that by measuring the success or failure of community action based on the presence or absence of social capital, the determinants and the consequences of the action become the same thing resulting in circular logic: social capital begets social capital. This entanglement of cause and effect, claims Portes (2000, p. 4), has been avoided by network analysts. For instance, Lin's approach separates cause and effect by proposing that the presence of high levels of social capital, based on empirically derived measures, results in better outcomes for the individual (Lin, 2001, p. 28). Appel et al. (2014) state that only by 'separating the structural component – social capital – from its outcome and contributors would it be possible to speak of the costs and benefits of social networks' (p. 399). For community researchers, however, logical circularity may in fact be the defining characteristic of community social capital; it is an asset that is built up through repeated interactions among people resulting in ever increasing familiarity and trust that enables individuals and communities to work together to share information as well as resolve their shared concerns. Although it can be argued that a more holistic view of social capital will include both perspectives, it may be impossible to devise a single method of measuring social capital that captures both individual and societal effects and is amenable to all research goals.

While library and information science researchers generally agree on what social capital consists of, i.e., the capability to work together to achieve common goals, the development of trust that permits information sharing or sense of community, or good quality resources accessed through relationships, the ways in which these effects are measured have not yet converged. Social network analysts and knowledge management researchers probably show the greatest consistency in their choice of measures. Interestingly, while Putnam's conceptualisation of social capital is the most commonly followed in community focused studies, very few library and information science researchers use the indicators that he developed for his Social capital community benchmark survey (SK 2006..., n.d.). Instead, several researchers use trust as a proxy for social capital, often measured through responses to the World values survey and General social survey question on trust: 'Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can't be too careful in dealing with people' (see for instance Varheim, Steinmo and Ide (2008) and Gong, Japzon and Chen (2008)). Others question whether social capital can be measured by just one indicator (Glaeser, Laibson, Scheinkman and Soutter, 2000) and whether the question, itself, is a valid measure of trust (Naef and Schupp, 2009). The main problem with social capital may be in its intuitive appeal; we know instinctively that who we know matters and that a good quality social network is important for the well-being of communities and individuals. However, some indicators of social capital including trust, norms and reciprocity may be too elusive to capture within a manageable number of variables.

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to determine how social capital is conceptualised and defined in library and information science research. To accomplish this, ninety-nine papers were identified through a search of library and information science periodical databases. Robert Putnam, who focuses on the societal benefits of social capital was the most frequently cited social capital scholar, followed by knowledge management scholars, Janine Nahapiet and Sumantra Ghoshal, and social network analyst, Nan Lin. Social theorist, Pierre Bourdieu, who provided the impetus for interest in social capital research in the 1980s, was also highly cited. Although library and information science researchers used numerous articulations of the concept of social capital, most were restricted to the definitions enunciated by these prominent scholars. The concept of social capital has been used to explain:

- how online communities and public libraries help to create or maintain social capital, (e.g., Ahn, 2012; Aabo, et al., 2010),

- how information is shared within and across organizations, (e.g., Huysman and Wulf, 2006; Bhandar, 2010),

- how social capital is either enhanced by or necessary for the successful implementation of information and communication technology projects in communities and the adoption of such technologies by individuals (e.g., Hui, et al., 2013; Williams, 2012), and

- the factors in social relationships that result in successful information seeking strategies (e.g., Johnson 2004; Veinot, 2010).

The different ways in which the concept has been interpreted and utilised, although often varying between community and individual perspectives, reflects an increasingly coherent research enterprise that demonstrates both the evolving nature of the concept and its flexibility in being relevant to different aspects of library and information science research. Nevertheless, there remain concerns about measurement validity that may have to be addressed before we can talk about one overarching theory of social capital.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers and journal editors for their most helpful comments and advice that greatly improved the original draft of this article.

About the author

Catherine Johnson is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Media and Information Studies at the University of Western Ontario. Her research on social capital was carried out with funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada and with the research assistance of Matthew Griffis now at the University of Southern Mississippi.