Illness perception and information behaviour of patients with rare chronic diseases

Snježana Stanarević Katavić, Sanjica Faletar Tanacković and Boris Badurina

Department of Information Science, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Osijek, Osijek, Croatia

Introduction

More than twenty years ago, Johnson, Meischke, Grau and Johnson referred to information seeking in the context of health as 'one of the primary functional coping strategies that individuals have at their disposal' (Rains, 2007, p. 668). Although some individuals choose to seek out information as a form of coping, while others may avoid it (Miller, 1987), health information seeking has become a common practice in the process of adjustment and living with illness on a daily basis. Literature indicates that health information seeking is an active, ´problem-focused coping´ strategy (Felton and Revenson, 1984, p. 346). Health outcome measures of information seeking are not systematised and their effects are difficult to identify; however, health information seeking is generally thought of as a proactive approach in illness management with a potentially positive influence on illness adjustment (Chou and Wister, 2005; Checton, Greene, Magsamen-Conrad and Venetis, 2015; Wyer, Earll, Joseph and Harrison, 2001). Research shows that illness management and adjustment is influenced by perceptions that patients hold about their illness.

Illness perceptions are the cognitive representations or beliefs that patients have about illnesses and medical conditions. As such, they are an important predictor of how patients will behave during their illness experience and are directly associated with a number of health outcomes (Petrie, Jago and Devcich, 2007). Generally, more positive illness perceptions are related to more positive illness management and health outcomes (Weinman and Petrie, 1997; Orbell et al., 2008; Fortenberry et al., 2014). Therefore, the question of how to contribute to building more positive illness perceptions among patients is becoming very important. Studies have shown that provision of adequate and customized health information to patients can influence the formation of more positive illness perceptions (Iskandarsyah et al., 2013; Husson et al., 2013; Rainey, 1985). Hence, it is legitimate to ask the question – are there any correlations between health information behaviour and illness perceptions and, if there are, which elements of health information behaviour are related to more positive illness perceptions that we want patients to build?

This study focused on patients suffering from rare diseases. There are several reasons for targeting this population. Rare diseases are very specific in terms of medical and non-medical knowledge about them, and in terms of the information that is available to patients. Rare diseases affect a limited number of individuals in the general population. A disease is defined as rare if its incidence is no more than one person in 2,000 individuals in the European Union, and no more than one person in approximately 1,250 people in the USA (Schieppati, 2008). The European Organisation for Rare Diseases (EURODIS) estimates that there are between 5,000 and 8,000 different rare diseases. Although individual rare diseases affect a small number of people, the total number of patients is relatively large and it is assumed to be between 6 and 8% of the world population. Knowledge about rare diseases, their causes, triggers and treatment options is scarce. This generates many questions concerning the role of health information and health information behaviour in illness coping of rare disease patients.

Due to the fact that rare diseases are de facto characterised by lack of medical knowledge, a label of rarity and incurability, and in Croatia, where this research was conducted, much information is still not available in the Croatian language, the previous questions are further amplified. Therefore, in the study presented in this paper we tried to answer the following question: are there any elements in rare disease patients’ health information behaviour (frequency of independent health information seeking, use of different information sources, health information avoidance) that are related to more positive illness perception, and conversely, to less positive illness perception?

This paper resulted from extensive (quantitative and qualitative) research into information needs and health information behaviour of patients with rare chronic diseases conducted in 2013 in Croatia. In this paper, only one segment of the quantitative part of the research is presented, focusing on the relationship between illness perception and the health information behaviour of patients with rare chronic diseases.

Rare disease patients’ health information behaviour

As health information becomes more widely and easily available, individuals are able to take a more active role in managing their own health, thus making health information behaviour an important issue to be understood. According to Budych, Helms and Schultz (2012) patients with severe illnesses prefer the physician to take a major role in the decision making process and to provide them with the necessary information. However, in the case of rare diseases, patients are forced to become experts in their own illness, given that knowledge about them is insufficient even among health professionals.

Health information behaviour of rare disease patients has not been extensively studied. The few studies that exist indicate that patients are not satisfied with the information that is provided to them, that they mostly lack information and support with their non-medical issues, that they have to make an effort to find the necessary information and that they rely mostly on their personal networks when seeking information. For example, in 2010 the National Alliance for People with Rare Diseases in the UK carried out a survey of patients and families affected by rare diseases. The aim of this survey was to identify common problems that people with rare diseases and their families often face. The survey covered multiple aspects of rare diseases including their access to information. Research has shown that patients and families lack information concerning their medical and non-medical problems, that information provision, at diagnosis and subsequently, is insufficient and that patient organisations are often the main or only source of information for rare disease patients. The authors of the study concluded ´These patients are left to their own initiative to find information on their condition (despite the fact that good-quality information is not always easy to find without guidance), or they may come across information only by chance´ (Limb, Nutt and Sen, 2010, p. 15). Therefore, patients with rare diseases often must seek necessary health information on their own and in the process they are often faced with different obstacles due to the lack of quality information. Caroline Huyard (2009) came to similar conclusions in a study of patients suffering from rare diseases in France, the aim of which was to find out to what extent patients with rare diseases believe that the rarity of their condition is the main cause of their problems and to what extent their difficulties are related to causes other than those that are traditionally referred to. Although the lack of medical knowledge is often cited as a problem that these patients face, this study showed that medical knowledge was not the primary concern of patients. Patients have expressed the need for information that would lead them in making health care decisions and emphasized the non-medical advice and information that was related to their everyday lives was extremely useful.

Seeking health information online, and in particular information sharing among people affected by rare diseases, proved to be an issue that needs special attention. A survey by the Pew Research Centre in 2011 on searching health information online included members of the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD), namely persons with rare diseases, their families and carers. When asked which sources of information they had used the last time they had a need for information about their disease, people with rare diseases more than any other group of respondents (including those suffering from chronic diseases), addressed their private social networks, primarily family members and friends, and other patients with the same diagnosis. Communication with patients who have the same diagnosis mainly takes place online, since, in many cases, patients do not know personally anyone with the same diagnosis. However, although these patients rely heavily on personal social networks, healthcare providers are still the most popular source of information (Fox, 2011).

The above research shows that independent health information seeking among people affected by rare diseases is not only a common practice, but a necessity, due to the general lack of health information and inadequate information provision by the healthcare providers. The literature describes numerous benefits of health information seeking in general. It is believed that health information seeking facilitates coping with health problems by enhancing proper understanding of health problems and their possible solutions. Also, it contributes to the self-management of health conditions and stress, as well as increasing the feeling of control, and potentially adds to positive health outcomes and psychosocial adaptation (Lambert and Loiselle, 2007). However, the question remains how this all applies to rare disease patients. We believe that by studying the relationship between health information behaviour and illness perception we can shed some light on this question.

Health information and illness perceptions

Illness perceptions are cognitive models that people have about symptoms, illnesses, medical conditions and health threats (Benyamini, 2011). Patients construct them to make sense of their symptoms and medical conditions and to cope with uncertainty. They are also known as patients' theories of illness, illness representations (Leventhal, Meyer and Nerenz, 1980) or personal models of illness (Lange and Piette, 2006). An illness perception consists of a number of interrelated beliefs about an illness and what they mean for the patient’s life. The major components of illness perception include how the illness was caused, how long it will last, what the consequences of the illness are for the patient’s life, the symptoms of the illness and how the condition is controlled or cured. It is believed that the way in which patients perceive their illness is a key factor in the type of psychological reaction they have to the illness, and subsequent behaviour and attitudes towards illness (Weinman and Petrie, 1997).

There are several versions of standardised questionnaires about illness perception in use. In 1996 Weinman, Petrie, Moss-Morris and Horne published The Illness Perception Questionnaire. Since then numerous studies on illness perceptions have been carried out with this instrument in its different versions. A revised version of the Illness Perception Questionnaire (the IPQ-R) was published in 2002 by Moss-Morris et al. Due to the length of the IPQ-R (about seventy items), Broadbent, Petrie, Main and Weinman designed the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) in 2006 (Benyamini, 2011). This version of the questionnaire is widely used because it can be administered quickly and has acceptable psychometric properties. This questionnaire examines the cognitive and emotional components of illness perception and consists of eight quantitative questions that respondents answer on a scale of 0 to 10, and one open ended response item dealing with causal representation. Five quantitative questions cover cognitive components of illness perception, one refers to the understanding of the disease and two to the emotional component of illness perception (Broadbent, Petrie, Main and Weinman, 2006).

In a meta-analysis of the research on illness perceptions carried out with Illness Perception Questionnaire instruments, Hagger and Orbell (2003) found that illness perceptions are related to many of the coping strategies and variety of outcomes: physical, role and social functioning, vitality, psychological distress and well-being. Negative illness perceptions are associated with impaired quality of life and negatively influence emotional adjustment and health-related outcomes across chronic illness populations (Tiemensma, Kaptein, Pereira, Smit and Romijn, 2011; Cherrington, Moser, Lennie and Kennedy, 2004; Zoeckler, Kenn, Kuehl, Stenzel and Rief, 2014; Iskandarsyah, Klerk, Suardi, Sadarjoen and Passchier, 2014). Because of this, the study of interventions aimed at changing inaccurate or negative perceptions of illness is becoming an important research topic in health psychology (Petrie and Weinman, 2012, p. 60).

One of the least studied topics in this area is related to how people form illness perceptions and what sources they draw upon. We know that illness perceptions are created by integrating medical information into our pre-existing understandings, experience and memories of health and illness. Information from health care providers is one of the main sources in that process. However, studies show that there are many other sources on which we base our illness perceptions. Illness perceptions are generally stable and more resistant to change in response to medical information, but they do evolve over time and tend to change as personal experience with the illness and information provided by similar patients accumulate (Benyamini, 2011).

No specific research that would explicitly examine the relationship between illness perceptions and information behaviour of rare disease patients had been located prior to the start of this study, but there are studies that indicate that there is a connection between the provision of adequate health information and more positive illness perceptions (e.g. stronger beliefs in personal control, lesser concerns about health condition, better understanding of illness, less emotional distress etc.) in patients with different chronic conditions (Iskandarsyah et al., 2013; Husson et al., 2013; Rainey, 1985). A more precise connection between health information behaviour and illness perceptions can be seen in a study of online support group members' information seeking by Hu, Bell, Kravitz and Orrange (2012). This study has demonstrated that the use of online health resources was connected to illness perception. Patients who believed they had control over their illness, and who attributed many symptoms and negative emotions to it, used online health resources to a greater extent. Furthermore, reliance on the online support group was highest among those who believed they had personal control over their illness, expected their condition to persist and attributed negative emotions to it.A recent study by Chen (2015) investigated how information use may affect illness representations among patients suffering from fibromyalgia. Findings indicate that the type and timing of information use affected individuals' perceptions of personal control. Also, differences in illness perceptions and information use across different participation styles in online support groups were detected.

Less positive illness perception might be associated with the rejection of additional health information due to the view that additional knowledge would make no difference (Dilger, Leissner, Bosanska, Lampe and Plöckinger, 2013). Generally, people tend not to seek information if they do not believe that knowing more about a topic will allow them to make a change (Case, Andrews, Johnson and Allard, 2005). Due to the lack of medical knowledge about rare diseases and their limited treatment options that make many rare diseases to a certain extent unmanageable conditions per se, the issue of illness perception and, not only health information seeking, but health information avoidance as well, is particularly intriguing.

Furthermore, patients who hold negative illness representations are more likely to report lower levels of accurate health information concerning the nature and intent of illness treatment and personal theories of illness causation (Buick, 1997).

From these studies we can draw a few general conclusions:

- provision and use of adequate health information at an appropriate time is related to more positive illness perception

- more negative illness perception might be associated with the rejection of additional health information

- the level of use of (online) health resources is related to illness perception (higher use is related to more positive beliefs about the illness).

Research into the connection between illness perception and the information behaviour of patients with rare diseases has not been carried out so far, therefore this research seeks to discover elements in the health information behaviour of patients with rare diseases that are related to more positive illness perception, and conversely, to less positive illness perception.

Research

The aim of this research is to find out what aspects of information behaviour are associated with more and less positive beliefs and feelings about rare diseases, in the hope that future information sources and services might support more productive information behaviour and more positive beliefs and feelings about rare diseases.

The objectives of this paper are:

- to analyse aspects of the cognitive, emotional and comprehensibility components of illness perception for patients with rare diseases

- to study information behaviour of patients with rare diseases, namely health information seeking frequency, information sources use and health information avoidance

- to discover if there is a correlation between the individual components of the patients' illness perception and their information behaviour

- to identify if there are any information behaviour elements that are connected to more positive, and less positive, illness perceptions.

Method

Print and online surveys containing questions about health information behaviour and illness perception were conducted on a sample representing adult patients suffering from three rare diseases (systemic lupus erythematous, scleroderma and myasthenia gravis) in Croatia in 2013. Out of 171 respondents who participated in the study, 146 respondents correctly completed the questionnaire.

Table 1 shows the number of sent, returned and correctly completed questionnaires in the print format.

| Source | Number of sent questionnaires | Number of returned questionnaires | Number of correctly completed questionnaires | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department of clinical immunology and rheumatology, university hospital centre Osijek | 100 | 31 | 17 | 17% |

| Croatian association of patients suffering from myasthenia gravis | 25 | 24 | 24 | 96% |

| Croatian association of patients with scleroderma | 70 | 25 | 25 | 35.7% |

| Association of patients with collagenosis Split | 30 | 20 | 13 | 43% |

| Total | 225 | 100 | 79 | 35.11% |

The online questionnaire was correctly completed by 67 (out of 71) participants. Together with 79 correctly completed questionnaires in print form, the total number of correctly completed questionnaires was 146.

Both print and online questionnaires were used in order to access as many respondents as possible and to reach different groups of respondents according to their usual practices of information seeking (for example, Internet users and non-users, patient support groups’ members and non-members, online patient support groups’ users and non-users).

Sampling

Since the study was aimed at adult patients who were seeking health information independently (to meet their own health-related information needs) the sample was narrowed down by the choice of rare chronic diseases that appear in adulthood and for which there are patient associations in the Republic of Croatia within the Croatian Alliance for Rare Diseases. Based on these two criteria, the sample was identified with the help of three Croatian non-governmental associations for rare disease patients: the Croatian Association of Patients with Scleroderma, the Association of Patients with Collagenosis Split and the Croatian Association of Patients Suffering from Myasthenia Gravis. Since there is no comprehensive epidemiological data on patients suffering from these chronic rare diseases in Croatia, a convenience sampling method was employed to obtain as many respondents as possible.

A total of 146 respondents participated in the study: 53 patients suffering from scleroderma, 51 patients diagnosed with myasthenia gravis and 42 systemic lupus erythematosus patients. The survey was filled out by 13 male (9%) and 132 female respondents (91%). All diseases included in the sample are female-predominant diseases and Table 2 shows the rate of women and men in the sample for each disease.

| Illness | Women | Men | Ratio of women versus men with the condition in general population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 95.2% | 4.8% | 90:10 |

| Myasthenia gravis | 84.0% | 6.0% | 60:40 |

| Scleroderma | 94.3% | 5.7% | 60-80:40-20 |

The largest age groups of respondents were 31-40 (N=35, 24%) and 61-70 (N=30, 20.5%). This was followed by the age groups 51-60 (N=29, 19.9%), 21-30 (N=28, 19.2%) and 41-50 (N=16, 11.6%). The smallest groups were the age group 0-20 (N=4, 2.7%) and those over 71 (N=3, 2.1%). The average treatment duration was 11.5 years, with a minimum of 0.5 year and a maximum of 41 years. Slightly over half of the respondents (55.5%, N=80) indicated that they were members of associations of patients suffering from rare chronic disease, and a large majority of respondents (71.6%, N=101) said that they had a friend or an acquaintance with the same diagnosis.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire used in this study had twenty-eight questions, with a mix of multiple choice and open-ended questions. For the purposes of this paper we only deal with a portion of the results, therefore, only those questions relevant to the chosen topic in this paper will be discussed. Prior to its launch, the survey was tested with individuals of varying ages and occupations to ensure general readability and interpretability of the items.

In order to assess the respondents' illness perception, questions from the official Croatian version of The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) were used. This comprises eight items rated on a 0–10 scale representing three dimensions of illness perception: cognitive illness representations (five items), emotional representations (two items), illness comprehensibility (one item) and one open-ended response item assessing causal representation (Broadbent et al., 2006). In this research we wanted to concentrate on illness perception dimensions that are prominent in the literature on coping with chronic illness. Based on the literature on the topic (Peterson and Stunkard, 1989; Taylor, Helgeson, Reed and Skokan, 1991; Moss-Morris et al., 2002; Falvo, 2010) we came to the choice of three questions representing three illness perception dimensions: personal control representing cognitive illness representations (How much control do you feel you have over your illness?), concern representing emotional illness representations (How concerned are you about your illness?) and illness comprehensibility (How well do you feel you understand your illness?). These three dimensions are not only prominent in the literature of coping with chronic illness, but they are also interconnected and seem to influence one another (Chen, 2015). Throughout the questionnaire, for each question that was in the form of a numeric scale, a five point Likert-type scale with accompanying explanations of each level on the scale was used. Since testing of the questionnaire showed that original scaling in the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire without accompanying explanations of each level on the scale caused confusion for respondents of older age and lower educational level, the same five point Likert-type scale was applied to the questions on illness perception.

In the information behaviour section of the questionnaire, answers were sought to questions relating to the frequency of the respondents' health-related information seeking, information sources use and avoidance of health information. These questions were chosen in order to get an insight into the aspects of information behaviour that support more and less positive beliefs about rare diseases with the aim to inform strategies for information support for rare disease patients and future studies of their health information behaviour.

For health information seeking behaviour: 1) the frequency of its occurrence was measured on the scale from 1 to 5 (1 – never, 5 – very often), 2) information sources use was analysed in a form of a closed multiple choice question Which information sources do you usually use when seeking health information regarding your diagnosis? This question contained a list of eleven information sources that respondents could choose, with an additional blank space that gave respondents a possibility to provide their own additional answers. These questions were self-administered, but based on a review of literature on health information seeking (Detmer et al., 2003; Dutta-Bergman, 2004; Finney Rutten, Arora, Bakos, Aziz and Rowland, 2005).

In relation to information avoidance, three slightly modified elements have been employed from the 2003 study undertaken in the UK (UK Colorectal…, 2003): I would rather not read about the potential complications; I do not like to talk about my illness; I avoid reading about my illness. Respondents had to indicate the level of their agreement with these statements on a five point Likert-type scale (1 – fully disagree, 5 – fully agree).

The questionnaire also contained a question regarding participants’ perception of health information availability. The question stated ‘How would you rate the availability of health information regarding your diagnosis in the Croatian language on the Internet?’ and used a five point Likert-type scale (1 –very poor, 5 – excellent).

Data analysis

Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses were derived for testing:

- rare disease patients who more frequently seek health information have significantly more positive illness perception in all three senses (personal control over the illness, concern about the illness and understanding of the illness)

- there is a statistically significant difference in illness perception according to type of information sources used

- rare disease patients who more frequently avoid health information have significantly less positive illness perception in all three senses (personal control over the illness, concern about the illness and understanding of the illness).

Quantitative analyses were carried out using the SPSS statistical package. Besides descriptive statistics, Chi-Square test, T-test and non-parametric Kruskal Wallis test were used to test possible differences between the groups in the sample. Spearman's rank correlation was used for testing statistical dependence between variables. Statistical difference was tested at the level of 95%.

Results

In the first section, results concerning three illness perception components are presented (personal control over the illness, concern about the illness and understanding of the illness). Following sections present results dealing with individual elements of health information behaviour (health information seeking frequency, information sources use and health information avoidance) and their correlation with illness perception.

Illness perceptions

Three questions from The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire were used to assess three components of illness perception among respondents – personal control (How much control do you feel you have over your illness?), concern (How concerned are you about your illness?) and understanding of the illness (How well do you feel you understand your illness?).

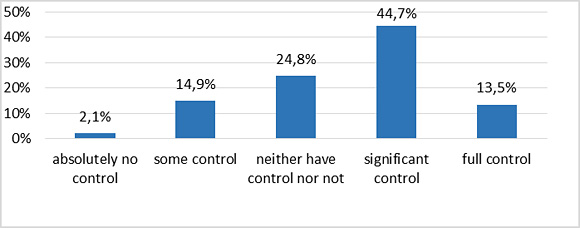

Figure 1 shows patients' perception of control over their illness. 17% of respondents indicated that they had absolutely no control or some control over their illness, 24.8% of respondents felt they neither had nor did not have control over their illness, while more than half of respondents (58.2%) indicated they had significant or full control over their illness.

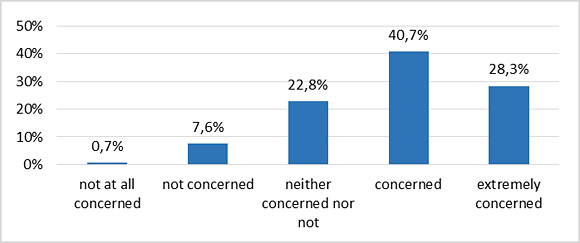

Figure 2 presents patients' concern about their illness. 8.3% of respondents indicated that they were not concerned about their illness. 22.8% indicated that they were neither concerned nor not concerned and a high majority (69%) indicated that they were concerned or extremely concerned about their illness.

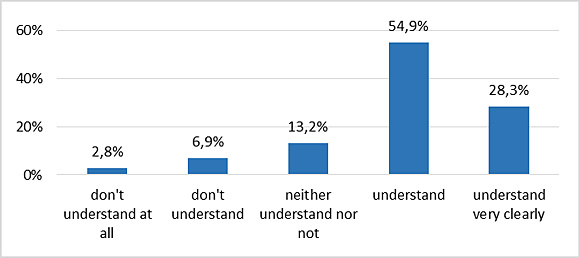

Figure 3 presents patients' understanding of their illness. 9.7% of respondents indicated that they did not understand their illness. 13.2% indicated that they neither do nor do not understand their illness. The greatest number of respondents (83.2%) indicated that they understand or understand very clearly their illness.

Correlation tests showed that there was a negative correlation between the length of the respondents' treatment and the level of concern about their illness. Correlation was weak but statistically significant and indicated that respondents with shorter treatment periods were more concerned and vice versa (r=-0.224, p=0.007).

Statistically significant positive correlation was identified between the control and understanding of the illness. Respondents who indicated that they understood their illness better also indicated more often that they had more control over their illness (r=0.401, p=0.000).

The correlation test indicated that there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the level of respondents' understanding of the illness and the length of their treatment. As expected, respondents who had been treated for longer periods indicated more often that they understood their illness and vice versa (r=0.401, p=0.000).

Health information seeking frequency and illness perception

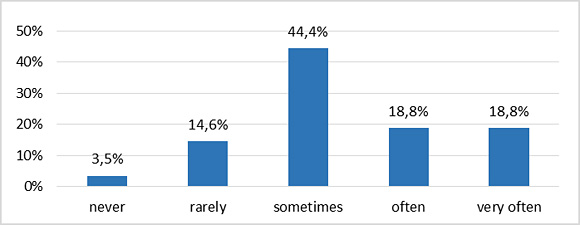

When asked ‘how often do you seek health information related to your diagnosis?’ on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 – never, 5 – very often), 18.1% of respondents indicated that they never or rarely seek health information related to their diagnosis, 44.4% said they sometimes seek this kind of health information, and 37.6% said that they often or very often seek health information related to their diagnosis. Figure 4 shows distribution of the results.

In order to analyse correlation between health information seeking and illness perception components the following null hypotheses were formulated:

- N01: there is no statistically significant correlation between the frequency of health information seeking and concern about the illness.

- N02: there is no statistically significant correlation between the frequency of health information seeking and personal control over the illness.

- N03: there is no statistically significant correlation between the frequency of health information seeking and understanding of the illness.

Regarding the first null hypothesis, the correlation test showed that there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the frequency of health information seeking and concern about the illness. Respondents who reported that they sought health information more frequently also reported a higher level of concern about their illness (r=0.307, p=0.000). Therefore, the first null hypothesis is rejected.

Correlation tests did not show statistically significant correlations between the frequency of health information seeking and personal control over the illness nor understanding of the illness. Therefore, the second and the third null hypotheses are accepted.

Information sources use and illness perception

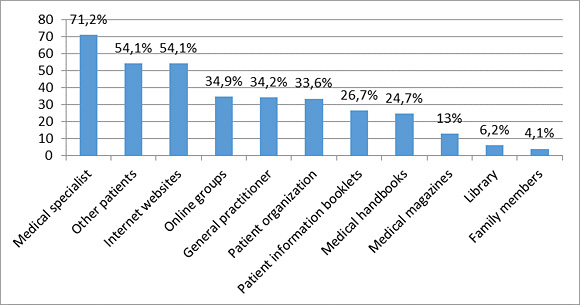

Information sources use was analysed through a closed multiple choice question: which information sources do you usually use when seeking health information regarding your diagnosis? Respondents were given a list of eleven information sources and asked to mark all the sources that they usually consult when they need health information related to their diagnosis. Results indicating a percentage of respondents that use each information source are shown in Figure 5.

The following null hypothesis was set to analyse whether there was a difference in illness perception in relation to the use of different information sources:

- N0: there is no statistically significant difference in illness perception according to the type of information sources used.

The difference in the illness perception was analysed by nonparametric Kruskal Wallis test.

A statistically significant difference in the illness perception was determined between the respondents who stated that they used patient associations as information sources and those who did not (p=0.011). Respondents who used patient associations as a source of information reported a higher level of understanding of their illness. On the other hand, a higher level of concern about the illness was found to be connected to using general practitioner (p=0.019), online groups (p=0.007) and family members as information sources (p=0.006). Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected for patient associations, general practitioner, online groups and family members as information sources.

Although the Kruskal Wallis test did not show a statistically significant difference in illness perception between the respondents who stated that they acquired health information from other patients suffering from the same disease and those who did not, the Kruskal Wallis test showed that there was a statistically significant difference regarding the illness perception if respondents had acquaintances with the same diagnosis. Table 2 shows that patients having acquaintances with the same diagnosis perceived that they had more control over their illness, were less concerned about their illness and understood their illness better.

| Statement | Acquaintance with the same diagnosis | Mean rank | Statistical difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| How much control do you feel you have over your illness? | Yes | 73.42 | p=0.031 |

| No | 58.28 | ||

| How concerned are you about your illness? | Yes | 66.59 | p=0.032 |

| No | 82.14 | ||

| How well do you feel you understand your illness? | Yes | 75.98 | p=0.005 |

| No | 56.80 |

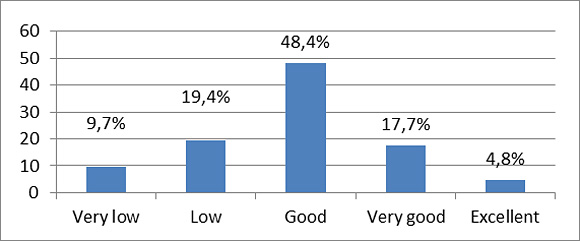

Respondents were also asked to rate the availability of rare disease information on the Internet in the Croatian language on a scale from 1 (very low) to 5 (excellent). The distribution of responses is shown in Figure 6. Almost one third of the respondents (29.3 %) assessed the availability of rare disease information as low or very low, almost half of the respondents judged that the availability of such information was good (48.4 %), while 22.5% rated the availability of health information as very good or excellent.

Results indicate that the perception of health information availability on the Internet is related to illness perception. Statistically significant correlation was determined between personal control over the illness and the availability of health information (r=0.201, p=0.028), and between understanding of the illness and the availability of health information (r=0.217, p=0.016). In other words, respondents who rated the availability of health information about their diagnosis higher had more positive perceptions of control over their illness and their ability to understand the illness. Respondents who perceived the availability of information about their diagnosis to be lower had more negative illness perceptions about personal control and understanding of the illness.

Avoidance of health information and illness perception

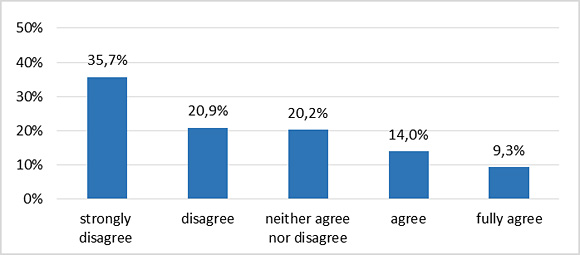

Health information avoidance was tested by three statements whereby respondents indicated the level of their agreement on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 – fully disagree, 5 – fully agree). In relation to the first statement I would rather not read about the potential illness complications, the largest number of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement (56.6%, N=73), while only slightly over 20% (23.3%, N=30) agreed or fully agreed with that statement that they would rather not read about the potential complications (Figure 7).

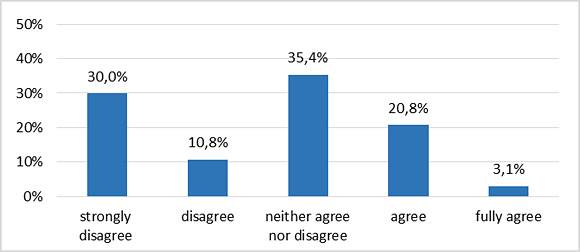

In relation to the next statement, I do not like to talk about my illness, the majority of respondents (40.8%, N=53) reported that they disagreed or fully disagreed with that statement, 35.4% (N=46) said that their neither agreed nor disagreed and 23.9% (N=31) of respondents said that they agreed or fully agreed with it (Figure 8). In other words, almost a quarter of respondents did not like to talk about their illness.

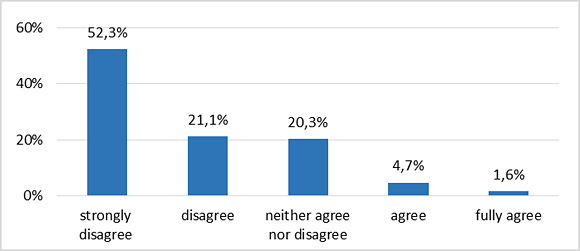

The last statement was I avoid reading about my illness. The majority of respondents (73.4%, N=94) reported that they disagreed or fully disagreed with that statement, 20.3% (N=26) said that their neither agreed nor disagreed and 6.3% (N=8) of respondents said that they agreed or fully agreed with it. All values are presented in Figure 9.

In order to analyse correlation between health information avoidance and illness perception the following null hypotheses were formulated:

- N01: there is no statistically significant correlation between agreement with the statements on health information avoidance and concern about the illness.

- N02: there is no statistically significant correlation between agreement with the statements on health information avoidance and personal control over the illness.

- N03: there is no statistically significant correlation between agreement with the statements on health information avoidance and understanding of the illness.

The correlation tests did not show a statistically significant correlation between the health information avoidance statements and concern about the illness. Therefore, the first null hypothesis is accepted.

The correlation test of illness perception and information avoidance statements showed that there was weak but statistically significant negative correlation between personal control over the illness and agreement with the statement I would rather not read about the potential illness complications (r=-0.199, p=0.025). Respondents who reported less personal control over their illness were more likely to indicate that they would prefer not to read about potential complications related to their illness. Therefore, the second null hypothesis is rejected regarding the statement I would rather not read about the potential illness complications.

Also, a weak but statistically significant negative correlation was identified between understanding of the illness and agreement with the statement I would rather not read about the potential illness complications (r=-0.188, p=0.033). Respondents who reported lower understanding of the illness were more likely to indicate that they would rather not read about the potential complications of their illness. Therefore, the third null hypothesis is rejected regarding the statement I would rather not read about the potential illness complications.

Discussion

Illness perceptions are the cognitive representations or beliefs that patients have about their illness and are directly associated with a number of outcomes in chronic illness, including self-management behaviours and health-related quality of life (Petrie et al., 2007). Because of the impact of illness perception on treatment outcomes, the study of interventions aimed at changing inaccurate or negative perceptions of illness is becoming an important research topic in health psychology (Petrie and Weinman, 2012). As noted, patients with rare diseases face uncertainties over the lack of knowledge about diagnosis and management of their condition, and they may need to be more active themselves in information seeking. In addition, such active information behaviour may be related to more positive illness perceptions and hence to better patient outcomes.

Although we did not identify prior studies that have specifically dealt with rare disease patients’ health information behaviour and illness perceptions, there are studies that point to the following:

- provision and use of adequate health information at an appropriate time is related to more positive illness perception

- more negative illness perception might be associated with the rejection of additional health information

- level of use of (online) health resources is related to illness perception (higher use is related to more positive beliefs about the illness).

In accordance with the existing knowledge about the relationship between health information and illness perceptions, three main hypotheses were set in this research:

- rare disease patients who more frequently seek health information have significantly more positive illness perception in all three senses (personal control over the illness, concern about the illness and understanding of the illness)

- there is a statistically significant difference in illness perception according to type of information sources used

- rare disease patients who more frequently avoid health information have significantly less positive illness perception in all three senses (personal control over the illness, concern about the illness and understanding of the illness).

This research shows that independent health information seeking is a common practice for many rare disease patients (more than a third of the respondents said that they seek health information often or very often). Despite the assumption that the characteristics of rare diseases may condition more negative illness perceptions, a great majority of respondents in this research had rather positive aspects of illness perception. It is likely that characteristics of the sample contributed to the results concerning illness perceptions in this research (55.5% of the respondents were members of patient associations, 71.6% of the respondents had acquaintances with the same diagnosis, the average lapsed time since the disease onset was 11.5 years). However, seeking health information was not related to more positive illness perceptions. Patients who sought health information more often did not report higher levels of understanding of the illness or stronger sense of personal control over the illness, only higher levels of concern. Studies on patients with more common chronic conditions have shown that there is a connection between the provision of adequate health information and more positive illness perceptions (Iskandarsyah et al., 2013; Husson et al., 2013; Rainey, 1985). Studies show that information provision that is tailored to the specific needs of patients may help patients to get a more coherent understanding of their illness that could lead to a better health-related quality of life (Husson et al., 2013). If rare disease patients who are active health information seekers do not feel that they understand their illness better, nor do they feel they have more personal control over the illness compared to the patients who are more passive in information seeking, then we can conclude that rare disease health information that is available and that patients independently acquire may be inadequate. Findings from research reported in this paper concur with the observation that for rare disease patients, lack of information about day to day management of the condition is a major problem (Limb et al., 2010). Like with any other condition, patients need health information that is tailored to their needs and broader than disease and treatment related information.

This research confirms the importance of patient associations and fellow patients in the rare disease experience from another perspective and provides evidence of this importance. Respondents who used patient associations as an information source reported higher levels of understanding of the illness. Respondents who had acquaintances with the same diagnosis reported more positive illness perception in all three aspects. On the other hand, patients who used general practitioners, online groups and family members as information sources reported more concern about the illness. The reasons for this finding are unclear. Examination of characteristics of each type of information source and types of health information that patients receive using them could provide an explanation for this finding.

Fellow patients are an important supportive mechanism not only for rare disease patients but in general, because they can provide empowering examples of how to deal with the challenges associated with illness (Fischer, 2011).However, the Pew Research Centre found that patients suffering from rare diseases are still more likely than any other group of respondents to use other patients as a source of information (Fox, 2011). Given the lack of information on the everyday management of rare diseases, this is expected. We know that illness perceptions change as personal experience with the disease accumulates and as patients get an insight into the experiences of others with the same diagnosis (Benyamini, 2011). Results from this research confirm the latter observation and prove that fellow patients undoubtedly have an important role in shaping rare disease illness perceptions.

As expected, health information avoidance was related to less positive illness perception. The correlations were relatively low but they indicated that respondents with less control over illness and lower understanding of the illness were also more likely to avoid seeking information about potential illness complications. This research, therefore, confirms the already observed relation between health information avoidance and less positive illness perception (Dilger et al., 2013). While, on one hand, in the results of this research we have grounds to assume that the relationship between health information seeking and illness perception is conditioned by the type and amount of available health information, on the other hand, a question arises about which are the mediating variables between illness perception and avoidance of health information, and whether the relationship between illness perception and avoidance of health information is universally negative. In any case, health information avoidance presents a problem because not only the adverse information that may contribute to anxiety is avoided, but also the information that can contribute to health management.

Results of this research also indicate that the perception of the health information availability is related to the illness perception. Respondents who perceived the availability of information about their diagnosis to be higher had more personal control over the illness and higher levels of understanding of the illness, and vice versa, respondents who perceived the availability of information about their diagnosis and treatment to be lower had a more negative illness perception.

By studying correlation between information behaviour and illness perception, information behaviour elements that are associated with more positive and less positive illness perceptions can be determined. This research, therefore, shows that there are valid reasons for studying correlation between health information behaviour and illness perceptions.

Conclusion

Research reported in this paper provides us with two lines of conclusions: one related to rare disease patients' illness perception and their information behaviour, and a more general conclusion related to studying correlation between illness perception and health information behaviour.

The relationship between health information seeking and illness perception indicates that we need to look more carefully at the real information needs of rare disease patients in order to provide health information that will contribute to fostering a more positive illness perception. Although this study confirms the popularity of healthcare providers as a source of information among rare disease patients, their use as information sources was not connected to patients’ illness perception. On the other hand, the importance of fellow patients is confirmed by demonstrating that respondents who had acquaintances with the same diagnosis had more positive illness perception in all three tested aspects (control, concern and understanding). Also, respondents who used patient associations as information sources were more likely to feel that they could understand their illness better. This is an important message not only to patient support groups, but to health care providers as well. Health care providers need to take advantage of their position as the most popular source of information and provide adequate health information to rare disease patients, preferably in cooperation with patient associations. Because of the undeniable importance of other patients in rare disease experience, patients need to be directed to patient associations as soon as they are given the right diagnosis. Also, Websites containing information on rare diseases need to provide space for communication among patients.

On a more general level related to health information behaviour research, this study shows that there are valid reasons for studying correlation between illness perception and information behaviour. By studying correlation between health information behaviour and illness perception we can determine information behaviour elements that are related to more positive and less positive illness perception, and therefore more and less positive coping strategies. Health information behaviour research might need to look at illness perceptions as mediating variables between information behaviour and health outcomes. Too often it is assumed that more information seeking directly influences better patient outcomes.

There are a few limitations to this study. Since this survey was conducted in Croatia where the information support system to those suffering from rare diseases is underdeveloped, generalization of these results might be limited. Also, given the limited number of rare disease associations that exist in Croatia, the sample in this study involved patients suffering from three rare diseases. It would therefore be useful to confirm the results on a wider sample of patients suffering from various rare diseases and also consider the influence of gender.

The results from analyses reported here highlight areas for future research. It would be useful to investigate factors that influence the relations between health information behaviour and illness perceptions. In future studies, it may be useful to investigate the reasons behind the finding that the frequency of health information seeking is not related to illness perception in rare disease patients. Also, perceptions that information is less available is something that needs to be looked at more carefully to determine the reasons for their connection to less positive perceptions about control and understanding of the illness. Qualitative research is required to examine what people gain from particular information resources and why some affect illness perceptions more than others.

About the authors

Snježana Stanarević Katavić is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Department of Information Science, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Osijek, Croatia. Her areas of interest include human information behaviour, health information, information credibility assessment and reading habits and interests.

She can be contacted at: sstanare@ffos.hr. ORCID No. orcid.org/0000-0001-5413-3261.

Sanjica Faletar Tanacković is Associate Professor in the Department of Information Science, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Osijek, Croatia. Her research interests are in convergence of cultural heritage institutions, library and museum services to the underprivileged and human information behavior. She can be contacted at: sfaletar@ffos.hr. ORCID No. orcid.org/0000-0001-7387-6458

Boris Badurina is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Information Science, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Osijek, Croatia. His research interests include information behaviour and social media use. He can be contacted at: boris.badurina@ffos.hr.