Internationality in Finnish research: an examination of collaborators, citers, tweeters, and readers

Fereshteh Didegah, Ali Gazni, Timothy D. Bowman and Kim Holmberg

Introduction. Internationalisation in science is recognized as an important factor towards academic quality and economic growth. This study examines the internationality rate of Finnish research publications in terms of tweeters, Mendeley readers, collaborators and citers.

Method. The publication and citation data were retrieved from Web of Science. Tweeter information was retrieved through Twitter API and readers information was obtained from Mendeley API. Research internationality was measured by examining the geographic dispersion of authors, citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers of research articles using Euclidean distance.

Results. The findings demonstrate that the internationality rate of Finnish research in terms of its citers is significantly higher than that of its Mendeley readers, tweeters, and collaborators. Internationality rates vary across disciplines and that rates are higher for Medical and Health Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Engineering and Technology than Humanities and Social Sciences. International research collaboration is found to be an important factor for higher rates of international visibility, and that particularly more collaborative subject domains (i.e. Medical and Physical Sciences) have a higher rate of internationality of authors and audiences. International staff engagement in the research conducted at Finnish universities is also an important factor and significantly associates with the internationality of Finnish research collaborators and audiences.

Conclusions. The findings will be informative for research policy makers and administrators engaging in research evaluation at Finnish institutions to develop international networks to enhance internationality of their research.

Introduction

Universities are strongly advised to maximize their internationalisation efforts (including research and teaching components) to keep pace with globalisation (Adams and Carfagna, 2006). Traveling scholars and students in the first decades of the sixteenth century who aimed at gaining experience and advantages from scholars beyond national borders were among the first to move science towards internationalisation; it has been shown that this first manifestation of internationalisation was associated with national innovation (Filippetti, Frenz, and Ietto-Gillies, 2011). Knight (2004) defined internationalisation as a “process of integrating an international, intercultural, or global dimension into the purpose, functions or delivery of postsecondary education”, but a comprehensive definition of internationalisation that parametrizes different manifestations and indicators of an institution’s internationalisation is yet missing (Hayward, 2000).

Internationalisation in science is recognized as an important factor towards academic quality and economic growth (Rostan, Ceravolo, and Metcalfe, 2014). Financial benefits of internationalisation (such as governmental funding for research publications that are a result of international collaboration or for international teacher exchange programs) motivate institutions to cross national borders and to internationalize their own systems. In addition to economic motives, socio-cultural (e.g., the dissemination of local culture and ideologies) and academic (e.g., international research collaboration and networking) benefits also motivate the internationalisation of institutions.

Internationalisation has many different aspects and manifestations that may function differently from one institution to another. One of the manifestations of internationalisation in universities is the internationalisation of research, which can be defined using a variety of dimensions including collaborating with researchers from other countries, publishing in international journals, participating in international conferences, or receiving funds from international agencies. Universities can greatly benefit from each dimension—for instance, international collaboration can provide researchers with the opportunity to gain international experiences and explore research problems that have the greatest impact on a global scale.

In bibliometric studies, research internationality has been widely explored by examining international research collaboration (Abramo et al., 2011), journal internationality in terms of the internationality of its authors, readers, and editorial boards (Kim, 2010; Yue, 2004; Zitt and Bassecoulard, 1998), and article internationality in terms of its authors and citers (Didegah, 2014). There is nevertheless a gap in the literature with regards to the influence of internationalisation on article impact. This study addresses this gap by examining the internationality level of Finnish research publications through the examination of their authors, citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers.

Research questions

No studies were found examining the internationality rate of authors, citers, tweeters, and readers of research papers across different institutions and subject domains. This study addresses this gap in the discourse by measuring the level of research internationality in Finland in terms of Finnish researchers’ collaborators and audiences. To fulfill the research goals, the following questions will be answered:

- How international is the research published by Finnish institutions and across different disciplines based on their authors, citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers?

- Do universities with a larger number of international staff members have more international authors, citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers?

Methods

Data collection

46,730 documents published by Finnish institutions from 2012 to 2014 and citation data to these documents were extracted from the Web of Science (WoS), Thomson Reuters. Out of the total publications, 37,183 documents had DOIs. To obtain Twitter data, the documents with DOI were searched through Twitter API resulting in a total of 13,623 documents that were tweeted at least once. Mendeley API was separately searched for the readership data; out of the 37,183 documents with DOIs, 35,980 documents were found in Mendeley.

The authors’ affiliation field for the matched publications was inspected to discover where the authors were geographically located. This resulted in the identification of 154 countries where the 140,211 authors involved in Finnish research originated from. The publications had 567,246 citers who were located across 170 countries. Moreover, 95,277 Twitter users tweeted about these publications and it was found that 63,507 (66.65%) of them had geographic location information recorded by Twitter and captured in the altmetric.com data – those tweeting about Finnish research came from 180 different countries. On Mendeley, 646,437 readers added Finnish publications to their library, out of which 127,789 (19.8%) readers from 163 countries were found to have information about their country location.

The institutional affiliation of authors was also investigated in order to analyze the internationality rates across Finnish institutions. With regards to institution name variations, a manual institutional-name disambiguation exercise was performed that included searching for different variations for each Finnish institution.

To examine the internationality rates across subject fields, each publication was mapped into one of the six OECD fields1: Natural Sciences, Engineering and Technology, Medical and Health Sciences, Agricultural Sciences, Social Sciences, and Humanities.

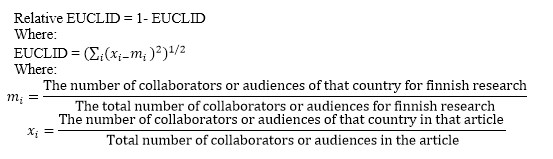

Internationality measure

There are absolute and relative approaches to measure research internationality. Relative approaches attempt to normalize for different factors such as national size (i.e. the internationality of total publications by the country) or subject field size, but absolute approaches are not normalized. There are, however, absolute indices such as Gini Coefficient that are easily calculated (Zitt and Bassecoulard, 1998). This work first implemented the Gini coefficient to measure the internationality of authors, citers, Mendeley readers, and tweeters, but when a manual check was completed of the Gini Coefficient for the current sample of articles it was discovered that the results were not accurate. The coefficient was primarily measuring the concentration of authors or audiences in a country regardless of how many countries they were originating from. Therefore instead of the Gini Coefficient it was determined that Euclidean distance would be a better fit for the data; Euclidean distance is a relative index normalized by country size. The Euclidean distance formula used by Gazni and Ghaseminik (2016) is:

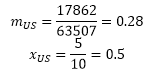

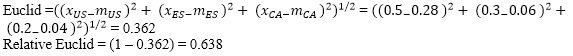

An example of Euclidean distance calculation is as follows:

The total number of tweeters who are tweeting about Finnish research publications is 63,507 tweeters, and the total number of tweeters from three selected countries is 17,862 (US), 3,914 (Spain), and 3,094 (Canada). As an example, a specific article has 10 tweeters who are from these three different countries; 5 tweeters from US, 3 tweeters from Spain, and 2 tweeters from Canada. To measure the Euclidean distance of tweeters for this article, the m_i and x_i was calculated for each of the tweeters’ country i.e. US, Spain, and Canada and the calculation for US is as follows:

The Euclidean distance for this article is calculated as below:

The Euclidean distance was manually checked against a sample of articles and it was found to provide accurate results. Henceforth, the Euclidean distance was used to measure the internationality of authors, citers, tweeters, and readers of Finnish research publications. The Euclidean distance is a value between 0 and 1, where the value of 0 represents the least level of internationality and the value of 1 represents the highest internationality.

Limitations

It was found that only 28% of Finnish publications had been tweeted on Twitter. The large amount of missing data may affect the research analyses. Furthermore, country information of tweeters and Mendeley readers is incomplete. Approximately 67% of tweeters’ geographic locations and 19.8% of Mendeley readers were identified for this study. However, in comparison with previous studies reporting that Twitter contains a very small percentage of geographic locations (Severo, Giraud, and Pecout, 2015; Graham, Hale and Gaffney, 2014), the percentage identified for this study is reasonably high.

Results

Research internationality level in Finland

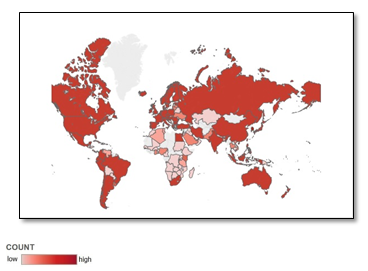

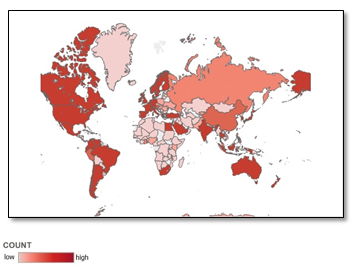

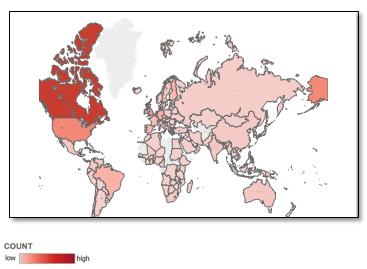

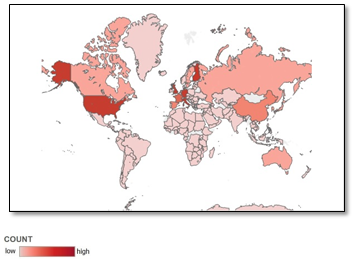

Research internationality was measured by examining the geographic dispersion of authors, citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers of research articles. The results demonstrate that citers of Finnish research and scholars who save Finnish publications to their Mendeley library have the highest internationality rate, while Finnish scholars’ co-authors are less geographically dispersed. The average internationality rate of citers and Mendeley readers (0.633 and 0.57, respectively) are significantly (Sig. < 0.05) higher than tweeters and collaborators per research paper (0.556 and 0.501, respectively) as confirmed by ANOVA test (Tables 1 and 2). Although those tweeting about Finnish research were geographically located across 180 countries, the distribution of the tweeters across the different countries is highly skewed, with approximately 68% of tweeters originating from 6 countries (the US, the UK, Spain, Canada, Australia, and Japan) and 48% of tweeters originating from only two countries (28.13% from the US and 20.23% from the UK). Only 3.9% of tweeters were found to be from Finland. The results found that citers of Finnish research are originating from 170 distinct countries around the world. Only 5.82% of total citers of Finnish research are from Finland. About 39% of citers are from the US, Italy, and the UK. The Mendeley API data revealed that readers came from 163 countries and that they were mostly found in Canada (27%). Around 4.08% of Mendeley readers came from Finland. Finnish collaborators originated from 153 different countries. It should be noted that around 31% of Finnish research collaborators are from the US, Italy, and the UK, which demonstrates that collaboration is important for citations as citers are also mainly from countries where collaborators are located. Approximately 24% of authors are Finnish (Table 3 and Figures. 1-4).

| Indicators | Avg. Euclide |

|---|---|

| Citer internationality | 0.633 |

| Reader internationality | 0.557 |

| Tweeter internationality | 0.556 |

| Collaborator internationality | 0.501 |

| ANOVA | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 36.006 | 3 | 12.329 | 353.231 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 810.15 | 22598 | 0.029 | ||

| Total | 856.19 | 22601 |

| TOP 10 CITERS | TOP 10 COLLABORATORS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | #citers | % citers out of total 567,246 | Country | #collaborators | % collaborators out of total 106,815 |

| US | 132999 | 23.45 | US | 23546 | 16.79 |

| Italy | 49611 | 8.75 | Italy | 11117 | 7.93 |

| UK | 36889 | 6.5 | UK | 8304 | 5.92 |

| Germany | 35753 | 6.3 | Germany | 6842 | 4.88 |

| Finland | 33030 | 5.82 | France | 4635 | 3.31 |

| France | 27936 | 4.92 | Sweden | 4134 | 2.95 |

| China | 20119 | 3.55 | Spain | 3571 | 2.55 |

| Spain | 19358 | 3.41 | Netherlands | 3482 | 2.48 |

| Canada | 15508 | 2.73 | Russia | 2279 | 1.63 |

| TOP 10 TWEETERS | TOP 10 READERS | ||||

| Country | #tweeters | % tweeters out of total 63,507 tweeters with known location | Country | #readers | % readers out of total 127,789 with known location |

| US | 17862 | 28.13 | Canada | 34635 | 27.1 |

| UK | 12849 | 20.23 | US | 15829 | 12.39 |

| Spain | 3914 | 6.16 | UK | 9606 | 7.52 |

| Canada | 3094 | 4.87 | Germany | 6110 | 4.78 |

| Australia | 2764 | 4.35 | Brazil | 5856 | 4.58 |

| Japan | 2583 | 4.07 | Finland | 5217 | 4.08 |

| Finland | 2479 | 3.9 | Spain | 4954 | 3.88 |

| Netherlands | 1843 | 2.9 | France | 3709 | 2.9 |

| France | 1518 | 2.39 | Netherlands | 2802 | 2.19 |

| Denmark | 1066 | 1.68 | Japan | 2756 | 2.16 |

Figure 1: Geographic dispersion of tweeters2

Figure 2: Geographic dispersion of citers

Figure 3: Geographic dispersion of readers

Figure 4: Geographic dispersion of collaborators

International collaboration and its influence on the article visibility

In bibliometric studies, publications are assigned to authors, institutions or countries through either full counting or fractional counting. In the full or standard counting, the publication credit is given to all authors while in the fractional counting for a publication with N authors, each author contribution counts for 1/N. Full counting is the common method used by many bibliometricians in research evaluation projects and is also used in the current study; publications with at least one author affiliated to a Finnish university were considered as a Finnish research publication. But the influence of collaboration and particularly international collaboration on geographic dispersion of publications audiences is inevitable. Finnish researchers are highly collaborative as 90.3% of publications are multi-authored and only 9.7% are single-authored. International collaboration has been rapidly growing in recent decades (Leydesdorff, Wagner, Park, and Adams, 2013) and Finnish researchers no exception. Between 2012 and 2014, Finnish researchers collaborated with researchers from 153 other countries. 54.4% of Finnish publications are the result of international collaboration and the number of foreign countries per publication counts for 4.7 countries on average.

A large number of previous studies found that international collaboration is advantageous for citation impact (Didegah and Thelwall, 2013; Sooryamoorthy, 2009; Glänzel, 2001) and also contributes to increasing altmetric counts (Didegah, Bowman and Holmberg, 2016). International collaboration influences the geographc dispersion of the visibility of research publications in such a way that Finnish publications that are co-authored with for instance American authors are expected to have higher visibility in the US. This may be due to the effects of the social networks of the authors, i.e. other researchers that know the American authors are perhaps more likely to use and share their work. A moderate association was also found between the citers, tweeters, and readers internationality and international collaboration of Finnish publications showing that publications collaborated with more number of countries, have more international citers, tweeters and readers. However, out of 180 countries tweeting Finnish research, 119 countries are the same as the countries of collaborators, 61 are different. In addition, Mendeley readers are from 163 countries, with 119 countries being the same as the countries of the collaborators and 44 different. Citers are from 170 countries, out of which 148 countries are the same as the collaborators’ countries and 22 countries are different from collaborators’ countries.

Overall, internationality of tweeters, readers, and citers is moderately influenced by international collaborative networks showing the significance of international collaboration on enhancing visibility of Finnish research across the world.

| Correlation | International collaboration |

|---|---|

| Citer internationality | 0.565 |

| Tweeter internationality | 0.477 |

| Reader internationality | 0.345 |

Internationality level across disciplines

Only 28% of Finnish publications contained altmetric events, which indicates there may be field biases in the altmetrics data. While a large percentage (about 40%) of total Finnish data from Web of Science are in Physical Sciences (including Engineering, Physics, Chemistry, Computer Science and Material Science), half of Finnish research matched with altmetrics are in health and biological sciences.

Medical and Health Sciences have the highest internationality rates of authors, citers, and readers, respectively. Social Sciences have the highest internationality rate of tweeters. Humanities research has the weakest performance based on all indicators. In general, internationality rates are higher for Medical and Health Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Engineering and Technology than for Humanities and Social Sciences (Table 4).

| Subject area\Indicators | Author internationality | Citer internationality | Tweeter internationality | Reader internationality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Sciences | 0.45 | 0.3 | 0.22 | 0.31 |

| Engineering and Technology | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.52 |

| Humanities | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| Medical and Health Sciences | 0.53 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| Natural Sciences | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.37 |

| Social Sciences | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.3 |

International labor input3 at universities and research internationality

To examine whether the international personnel engagement level might affect the internationality level of research at Finnish universities, the correlation between different research internationality indicators and percentages of labor input (man-years) by international staff in 12 Finnish universities (Table 5) was tested. Handekn School of Economics and University of Arts were left out from the analysis due to their comparably lower publication counts. The results indicate that greater international staff engagement positively associates with greater numbers of international authors and citers, although quite weakly for tweeters and Mendeley readers of university research (Table 6).

| University | International staff labor input | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | % of total staff | |

| Aalto University | 1981.61 | 26.48 |

| Lappeenranta University of Technology | 353.56 | 21.83 |

| Tampere University of Technology | 613.67 | 18 |

| University of Eastern Finland | 636.87 | 14.21 |

| University of Helsinki | 2549.74 | 20.33 |

| University of Jyväskylä | 609.53 | 13.74 |

| University of Lapland | 55.83 | 6.68 |

| University of Oulu | 875.49 | 18.09 |

| University of Tampere | 304.66 | 10.11 |

| University of Turku | 730.51 | 13.82 |

| University of Vaasa | 150.02 | 18.29 |

| Åbo Akademi University | 439.54 | 21.65 |

| Spearman | % international staff labor input |

|---|---|

| Author interationality | 0.413* |

| Citer interationality | 0.544* |

| Tweeter interationality | 0.286* |

| Reader interationality | 0.115* |

Discussion

In answer to the first research question, the findings demonstrate that the internationality rate of Finnish research in terms of its citers is significantly higher than that of its Mendeley readers, tweeters, and collaborators. However, in general, the internationality rate of research based on the four indicators ranges between 0.5 and 0.6, which shows a moderate to high rate of internationality. This may be a result of the strategy of the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture (beginning in the late 1980s), to consider internationalisation of research as a key policy for developing quality research in Finland (Hakala, 1998). While Hakala (1998) argued that small countries like Finland would find it difficult to receive international recognition, these results have found that the high internationality rate of Finnish research rejects his hypothesis. A high internationality rate indicates that the authors and audiences of Finnish research are widespread around the world.

The majority of collaborators and audiences were found to come from the US and the UK, which corresponds with results from Haustein and Costas (2015). They examined the geolocation of 1,489,669 tweeters from Altmetric.com and found that 30% of the tweeters were from the US and the UK. Haustein and her colleagues (2014) also investigated the countries of readers and tweeters of biomedical publications and found that highly read papers on Mendeley were primarily originating from the US and the UK and were tweeted by members of public and scientific community mainly in the US and the UK.

One reason for these findings could be the fact that the papers examined in this study were written in English and the collaborators and audiences often originated from English-speaking countries. It is interesting to also note that the citers were predominantly from the same countries as collaborators. Moreover, internationality of tweeters, readers, and citers is moderately influenced by international collaborative networks showing the significance of international collaboration on enhancing visibility of Finnish research from across the world.

It was found that internationality rates vary across disciplines and that rates are higher for Medical and Health Sciences, Natural Sciences, and Engineering and Technology than Humanities and Social Sciences (with the exception of higher internationality rate of tweeters of Social Sciences research). This finding confirms results from interviews with academic professors at Finnish universities that demonstrated that research internationality has different meanings in the soft sciences (Social Sciences and Humanities) than in the hard sciences (Medical, Natural, and Physical Sciences) (Hakala, 1998). Professors from the soft sciences reported that internationality was not an essential factor and that it does not necessarily lead to quality, while professors from the hard sciences reported that internationality was necessary for more successful funding applications and the accomplishment of quality research.

Different disciplines have different collaboration behaviors. As with previous studies, Natural and Physical Sciences (except for Mathematics) are typified by large research teams and are more collaborative than Social Sciences and Humanities (Gazni, Sugimoto, and Didegah, 2012). Larger teams have a higher chance of international collaboration, which suggests that more collaborative domains are expected to have more international author contributions resulting in attracting more international attention either by being cited in another work or being added to a Mendeley library for readership purposes. Multi-author research has a citation advantage and the multi-nationality of authors favors the citation advantage even more; the extent to which international collaboration associates with citation counts to articles is significantly higher than that of individual collaboration in all subject domains (Didegah, 2014). This indicates that international collaboration is an important factor for citation counts. As more citations indicates more citers, there is a greater possibility that the citers come from a wide range of geographical locations. In addition, articles with a higher number of international authors are expected to have more Mendeley readers and tweeters as the authors increase the chance of more international visibility for the article.

With regards to the second question, the results demonstrate that more international staff engagement positively associates with more international authors, citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers. This shows that more international engagement at universities matter also for the visibility of research publications worldwide. The percentage of international staff is important for different world rankings of universities (e.g., Times Higher Education4 or QS5 ); one reason for this could be that they bring international collaboration opportunities to universities and that higher international collaboration will increase the visibility of university products and services worldwide. The findings of this work also confirms the impact of international staff on more international collaboration as Finnish universities with a higher engagement of international staff have more international authors and consequently more international citers, tweeters, and Mendeley readers.

Conclusion

In sum, the findings show that the internationality rate of authors and audiences of Finnish research is at a moderate to high rate. The results suggest that international research collaboration is an important factor for higher rates of international visibility, and that particularly more collaborative subject domains (i.e. Medical and Physical Sciences) have a higher rate of internationality of authors and audiences. International staff engagement in the research conducted at Finnish universities is also an important factor and significantly associates with the internationality of Finnish research collaborators and audiences. The findings will be informative for research policy makers and administrators engaging in research evaluation at Finnish institutions to develop international networks to enhance internationality of their research.

1. http://incites.isiknowledge.com/common/help/h_field_category_oecd_wos.html; http://incites.isiknowledge.com/common/help/h_field_category_oecd.html

2. The map shows the number of tweeters of Finnish research from different countries around the world. The darker red the country, the more number of tweeters from that country.

3. See this for a definition of staff labor input: http://www.stat.fi/meta/kas/henkilotyovuosi_en.html

4. https://www.timeshighereducation.com

5. http://www.topuniversities.com

About the authors

Fereshteh Didegah is a postdoctoral researcher at Danish Centre for Studies in Research and Research Policy, Aarhus University (Denmark). She received her Ph.D. in 2014 from School of Technology, University of Wolverhampton (UK). Her research interests fall into two broad categories: Bibliometrics and Altmetrics and her main focus in both areas is on the motivations and reasons for citation and altmetric counts and their implications for research policy makers and research evaluators. She can be contacted at fdid@ps.au.dk.

Ali Gazni is an Assistant Professor in Regional Information Center for Science and Technology, Shiraz, Iran. He received his Ph.D. from Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz and his research interests are in bibliometrics and how to improve the scientific impact of the countries, universities and authors. He can be contacted at ali.gazni@ricest.ac.ir.

Timothy D. Bowman is an assistant professor in the School of Library and Information Science, Wayne State University, where he conducts research on altmetrics, scholarly communication, open science, and social media. Bowman received his Ph.D. from Indiana University, Bloomington. He can be contacted at timothy.d.bowman@wayne.edu.

Kim Holmberg is a postdoctoral researcher at the Research Unit for the Sociology of Education at the University of Turku, Finland, where he works on questions related to bibliometrics, altmetrics, open science, and social media. Holmberg is an Honorary Research Fellow at the Statistical Cybermetrics Research Group at the University of Wolverhampton, UK, and he holds the title of Docent in Informetrics at Åbo Akademi University, Finland.

References

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C.A., & Solazzi, M. (2011). The relationship between scientists’ research performance and the degree of internationalization of their research. Scientometrics, 86, 629–643.

- Adams, J.M., & Carfagna, A. (2006). Coming of age in a globalized world: The next generation. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

- Didegah, F. (2014). Factors associating with the future citation impact of published articles: A statistical modelling approach. PhD thesis. University of Wolverhampton, UK.

- Didegah, F., & Thelwall, M. (2013). Which factors help authors produce the highest impact research? Collaboration, journal and document properties. Journal of Informetrics, 7(4), 861-873.

- Didegah, F., Bowman, T.D., & Holmberg, K. (2016). Increasing our understanding of altmetrics: identifying factors that are driving both citation and altmetric counts. IConference 2016 Proceedings.

- Filippetti, A., Frenz, M., & Ietto-Gillies, G. (2011). Are innovation and internationalization related? An analysis of European countries. Industry and Innovation, 18(5), 437-459.

- Gazni, A. & Ghaseminik, Z. (2016). Internationalization of scientific publishing over time: Analyzing publishers and fields differences. Learned Publishing.

- Gazni, A., Sugimoto, C.R., & Didegah, F. (2012). Mapping world scientific collaboration: authors, institutions, and countries. Journal of the American Society for Information Science & Technology, 63(2), 323-335.

- Glänzel, W. (2001). National characteristics in international scientific co-authorship relations. Scientometrics, 51, 69-115.

- Graham, M., Hale, S.A. & Gaffney, D. (2014). Where in the world are you? Geolocation and language identification in Twitter. The Professional Geographer, 66(4), 568-578.

- Hakala, J. (1998). Internationalisation of Science. Science Studies, 11(1), 52-74.

- Haustein, S. & Costas, R. (2015). Determining Twitter audiences: geolocation and number of followers. Altmetrics15 workshop, Netherlands, Amesterdam, 9 October.

- Haustein, S., Larivière, V., Thelwall, M., Amyot, D., & Peters, I. (2014). Tweets vs. Mendeley readers: How do these two social media metrics differ? IT-Information Technology, 56(5), 207-215.

- Hayward, F. M. (2000). Internationalization of US Higher Education. Preliminary Status Report, 2000.

- Kim, M.-J. (2010). Visibility of Korean science journals: an analysis between citation measures among international composition of editorial board and foreign authorship. Scientometrics, 84, 505-522.

- Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of studies in international education, 8(1), 5-31.

- Rostan, M., Ceravolo, F.A., & Metcalfe, A.S. (2014). The internationalization of research. In The Internationalization of the Academy. Springer, Netherlands. pp. 119-143.

- Severo, M., Giraud, T., & Pecout, H. (2015). Twitter data for urban policy making: an analysis on four European cities. In C. Levallois (Ed.), Handbook of Twitter for Research. EMLYON.

- Sooryamoorthy, R. (2009). Do types of collaboration change citation? Collaboration and citation patterns of South African science publications. Scientometrics, 81(1), 177–193.

- Yue, W. (2004). Predicting the Citation Impact of Clinical Neurology Journals using Structural Equation Modeling with Partial Least Squares. Doctoral thesis, University of New South Wales.

- Zitt, M. & Bassecoulard, E. (1998). Internationalisation of scientific journals: a measurement based on publication and citation scope. Scientometrics, 41 (1-2), 255-271.