Conceptualising the role of digital reading in social and digital inclusion

Elena Macevičiūtė and Zinaida Manžuch

Introduction. The aim of the paper is to explore previous research on digital reading in relation to social and digital inclusion. It looks at the more general aspects of reading research and how digital reading research has built upon them or changed the previous approaches.

Method. The main method used for writing the paper is the literature review as mainly published research is analysed. The material for the review was selected from the results of search in Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar databases.

Analysis. The main focus of the analysis lies in the differences of how reading and digital reading are explored in relation to their capacity to address the reduction of inequalities, especially, digital inequalities, what kind of interventions have been used and what methods have been applied in various settings.

Results. The results of the literature analysis are mapped onto the matrix including the concepts of two theories: social cognitive theory and the levels of digital divide to identify those nodes crucial to the planned digital reading interventions.

Conclusion. Digital reading interventions are successful in increasing digital literacy and general literacy skills. The most significant achievement is in the groups with the lowest or absent literacy skills. It may mean that disadvantaged groups with moderate literacy levels may need different digital reading interventions to reach a breakthrough. The digital reading research has extended the concept of reading into the area of device manipulation, navigation within the text and searching of digital texts that brings it closer to information seeking and digital literacy issues.

Introduction

The authors of the paper are involved in a research project that aims to design digital reading training intended to diminish the digital divide of disadvantaged groups. It is clear that this is not the only possible means of conquering the digital divide, but the project focuses on the effects that could be achieved by digital reading. Thus, this paper provides a systemic review of research on digital reading directed to minimize digital and social exclusion and inequalities. We attempt to conceptualise the approach to designing of digital reading intervention that could contribute to diminishing digital and social exclusion.

This short paper is aimed at an in-depth understanding of the complex factors that contribute to digital and social inclusion and the research that shows the potential of digital reading in solving exclusion problems. Available research indicates the potential of digital reading to encourage more intensive use of technologies, a positive motivation towards the use of digital tools (Picton and Clark, 2015) and learning digital skills (Neumann, Finger and Neumann, 2017). Furthermore, it also indicates broader benefits of digital reading, such as, e.g., increased general level of literacy (Korat and Shamir, 2008; Schneps, Thomson, Chen, Sonnert and Pomplun, 2013) in various disadvantaged groups. It bridges the adoption of digital technologies with using various opportunities by disadvantaged social groups for better participation in society. As noted by Warschauer (2002), ‘the goal of using ICT with marginalized groups is not to overcome a digital divide, but rather to further a process of social inclusion’.

However, social inequalities often become the reason for digital exclusion: for instance, low income communities show lower digital reading comprehension than those with higher income (e.g., Leu et al., 2015; Henry, 2007); income, education level and other factors influence slow adoption of digital technologies for personal benefits (e.g., Nguyen and Western, 2007). It means that digital and social inclusion/exclusion are linked by reciprocal relations. Knowing the relations between digital reading and social and digital inclusion/exclusion may help to design programmes that will cope with negative conditions and effects and achieve positive change.

The aim of the paper is to explore previous research on reading and digital reading in relation to social and digital inclusion. It seeks to answer the following questions: 1) what is known about the relations between digital reading and digital divide? 2) how digital reading interventions affect the digital inequality? The answers feed into the design of the theoretical framework on testing digital reading (or other digital interventions) as a means of the digital inclusion and the reduction of digital inequalities.

Theoretical framework

Two theories form a basis for analysis of how reading in general and digital reading relate to social and digital inclusion. The concept of digital inequalities used in the project builds on the theory of digital divide created by van Dijk (2005). The model proposed by van Dijk (2005) provides an in-depth understanding of different levels of digital divide and avoid simplistic and narrow focus on technology haves and have nots (Warschauer, 2002). Social learning theory developed by Bandura (1971) is employed to analyse the interplay of social, personal and behavioural factors that lead to adoption of technological means for digital reading and subsequent benefits related to digital and social inclusion. The latter allows understanding what factors of social environment, personal attitudes and behaviour lead to reducing digital inequalities on each level of digital divide.

According to van Dijk’s (2005) theoretical approach, the distribution of resources (including access to digital technologies) and participation in society are dependent on personal and positional categorical inequalities. The exploitation of available resources, especially the digital ones, and deriving more or less benefits (in terms of economics, finances, education, labour or social networks) from their use affect the initial categorical inequalities, usually increasing them. However, this negative cycle is not given and with proper interventions may be turned around into diminishing digital divide as well as other social inequalities. Unequal access to digital technologies is especially dangerous in a networked society, in which people use them for education, commercial activity, work, social and political participation. Thus, it is very important to increase digital inclusion of disadvantaged groups.

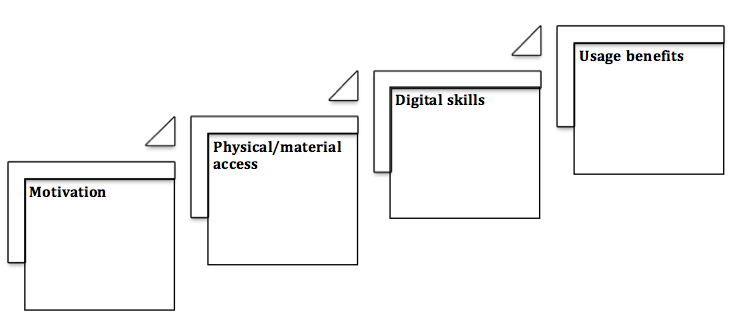

According to van Dijk (2005), the unequal access to digital technologies that lies at the bottom of digital divide, is a complex concept and includes several levels as seen in Fig.1.

The lack of physical access to digital equipment (physical/material access in fig. 1) is exacerbated by the preceding lack of motivation. Even when connectivity to the Internet is increased over time and when technologies become cheaper and wide-spread, the gap between digital skills and, especially, the derived benefits (fig. 1) does not disappear and may even increase (van Dijk, 2012) and again affect the motivation that is the main condition of the intention to use digital technologies.

The model of van Dijk (2005) shows different levels of digital exclusion, but it does not reveal what factors enable or inhibit the ability of a person to cope with challenges presented at each stage of digital divide. For this purpose, the social cognitive theory (STC) developed by Bandura (1986) is valuable. The theory explains how social learning occurs under various conditions and how particular patterns of behaviour are acquired by individuals and it is broadly applied not only in psychology and education – the setting, in which it was originally created, but also for exploring the factors of ICT adoption (Straub, 2009). The theory is based on reciprocal relations between three elements – environment, person and behaviour. Environment encompasses external social and physical factors that shape individual decisions and social learning practices (Carillo, 2010). For instance, it may be the influence of social surroundings – as friends or family, on taking decisions and adopting certain patterns of behaviour. Person refers to individual characteristics that cover demographic, cognitive and personality features and attitudes that affect decisions to engage in certain practices. For instance, fears and anxiety towards ICT can prevent or slow down the adoption of certain digital tools. And finally, behaviour is the actual course of action taken. Behaviour is interpreted by individuals and with reference to certain personal characteristics pre-condition how an individual will respond to certain environmental pressures or opportunities (Carillo, 2010).

Context: reading, information behaviour, and social inequalities

Reading is a complex phenomenon that is researched by different disciplines, such as neuroscience, psychology, education, sociology, literary research, library and information science and more. Reading is usually defined as a cognitive process that involves decoding symbols to arrive at meaning and is regarded as an active process of constructing meaning (Hultgren and Johansson, 2017). This cognitive process can be explored through direct investigation of processes in the brain by neuroscientists, or indirectly through investigating readers’ skills, such as, recognition of words or comprehension of texts by education researchers or psychologists. These two approaches, though leading to different results, are closely linked by the concept of literacy.

Initially, literacy was understood as a reader’s ability to read and write but was extended as people used more oral, digital and visual texts. At present, literacy also includes an ability to associate what one is reading to the own experience of the world and other texts, critically analyse texts and draw conclusions (Hultgren and Johansson, 2017). Reading is also a receptive skill as we receive information through it, but we may also attribute different meanings to the text. Thus, literary and communication scholars are interested in reception or making meaning of texts by individual readers and audiences (Jauss, 1982). This interest has led to the development of reader response and reception theories.

The concepts of literacy practices and reading practices have been the focus of interest of sociologists, education and information behaviour researchers. Literacy practice investigates literacy as a social practice common to communities, in which readers participate, rather than individual abilities. Reading practice research explores habits, routines and rules through which we acquire books, use them in different ways, values that are attached to books and texts by communities and enacted by individual readers (Hultgren and Johansson, 2017). Reading as information behaviour mainly belongs to this reading research direction (Ross, 2000; Liu, 2005, etc.), though information behaviour researchers have also explored its cognitive aspects (Juric, 2017) and emotional aspects.

Research that relates reading to social inequalities mainly looks at the issues of literacy and reading practices, but can also be included in all approaches of reading research.

Research has found that reading habits and skills generally are positively related to the social and economic status of people (Schubert and Becker, 2010). This influence is not direct but rather mediated by a variety of conditions in readers’ social environment (Stanovich, 1986). Neumann and Celano (2001) have demonstrated how children from low- or middle-income communities experience poor availability of print resources, even in public institutions such as public libraries and schools. Neurology researchers have found, that already at the start of life, children from middle-class families hear and learn many more words than those from working class families and thus gain advantage in learning to read. They gain more exposure to increasingly sophisticated texts and learn to coordinate multiple areas of knowledge (Wolf, Ullman-Shade and Gottwald, 2012, p. 234). This situation can even lead to reading disabilities in disadvantaged children (Wolf et al., 2012).

On the other hand, it was proved that having access to books, supportive adults, and the example of other readers can turn children into proficient readers despite other social and economic restrictions (Burgess, Hecht and Lonigan, 2002; Clark and Akerman, 2006). It is also known that being a poor reader as a child often leads to low satisfaction and social exclusion as an adult (Parsons and Bynner, 2002). BOP Consulting, which conducted a research literature review on non-literacy outcomes of reading for pleasure, for the Reading Agency, has found extensive benefits from enjoyment, to reducing ill health, acquiring social and cultural capital, increasing knowledge and empathy for others, as well as achieving personal success (BOP Consulting, 2015).

Methods of research

The search of the literature for review was conducted in the databases Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar . As we were interested in the studies relating digital reading to the social exclusion (or inclusion) and, especially, digital inequalities or digital divide, we have used the Boolean search combining the following keywords: social exclusion or social inclusion; digital divide or digital inequal* and digital reading. The results for the period 200-2017 are presented in table 1.

| Search string | Web of Science | Scopus | Google Scholar |

| digital reading | 195 | 343 | 10 700 |

| (digital divide OR digital inequal*) AND digital reading | 1 | 1 | 554 |

| (social exclusion OR social inclusion) AND digital reading | 0 | 0 | 163 |

| (social exclusion OR social inclusion) AND (digital divide OR digital inequal*) AND digital reading | 0 | 0 | 76 |

The search on the topic of interest in Web of Science and Scopus has produced minimal results, though two items that were produced were relevant to our study. The results of Google Scholar were most promising and we have explored the results of all three search strings for meaningful results. The string (digital divide OR digital inequal*) AND digital reading has produced results that focused on digital divide or on digital reading and mentioned the second keyword only in passing. Interestingly, the string (social exclusion OR social inclusion) AND digital reading produced many studies related to information or digital literacy programmes and their evaluation, which was not the focus of our investigation, but also included some relevant results. The string (social exclusion OR social inclusion) AND (digital divide OR digital inequal*) AND digital reading has included some irrelevant results, but also the ones that were very relevant. From the results of two final searches in Google Scholar we have selected 43 relevant empirical studies and added two that were produced by search in Scopus and Web of Science.

We have used the method of qualitative content analysis using open coding categories based on the levels of digital divide. First we focused on the studies that demonstrated how social and digital inequalities affect digital reading. Further, we concentrated our attention on the effects of digital reading interventions on the diminishing digital divide, but also on its social inclusion or increased digital competence and/or literacy effects. The texts were coded by one researcher and the assigned codes were checked by another. When the opinions on assigned codes differed, a common decision was used by discussing the issue. The third step included mapping of the results onto the matrix of the conceptual framework combining two theories introduced above.

Results: digital reading, social and digital in/exclusion of disadvantaged groups

Digital reading has instigated an increased wave of reading research largely regarding changing preferences for reading in different formats (Zhang and Kudva, 2014; Bergström and Höglund, 2014; Kurata, Ishita and Miyata, 2017; Baron, Calixte and Havewala, 2017). The preference for print is clearly expressed in findings of these researchers, though the number of people who read digitally is increasing (Gartner Inc., 2011; Bergström and Höglund, 2014) and some groups of readers spend equal or more time reading digitally as in print (Tenopir, Volentine and King, 2012). The most recent research suggests that

it is important to avoid the dichotomy of paper vs. screen or pen vs. keyboard. The current situation is much more complex particularly when old and new technologies exist side-by-side providing a myriad number of alternatives and complementary roles (Farinosi, Lim and Roll, 2016, p. 419).

Researchers compare reading experience and outcomes in print with reading on screen in various ways. The findings of this research are quite contradictory. Some of it demonstrates loss of orientation and diminished comprehension while reading on digital devices (Ackerman and Goldsmith, 2011; Kim and Kim, 2013; Mangen and Kuiken, 2014) and lacking the usual information clues embedded in a printed book (Gerlach and Buxman, 2011; Mangen, Walgermo, and Brønnick, 2013). Others find little difference in the outcomes and effects of reading digitally or in print (Margolin, Driscoll, Toland and Kegler, 2013) or relate similar levels of comprehension depending on the familiarity of a reading device to the readers (Chen, Chang, Zheng and Huang, 2014).

Some studies also demonstrate that suitable integration of reading devices and e-books can improve students reading achievements (Union, Walker Union and Green, 2015). Legge (2016) has reviewed the tests of digital reading devices and their impact on reading of visually impaired people and has concluded that digital reading enhances their access to texts by manipulation of magnification, spacing or contrast. Another group of studies show limitations of e-books as requiring additional skills of manipulation of reading devices and software, lacking intuitively understood tactile features, but also appreciate general emancipating features of e-books, such as ease of access around the clock, low price, saving space, adaptation to ones work tasks, reading and life style, etc. (Hillesund, 2010; Hupfeld, Sellen, O’Hara and Rodden, 2013).

Some research of elderly adults have shown that subjective perception of digital reading difficulties often differs from actual reading performance. Kretzschmar et al. (2013) used eye- tracking software to evaluate reading comprehension and performance in elderly adults. The researchers found that reading from a tablet reduced the reading effort for older adults (and only for them) when compared with using an e-reader or a printed book. However, the elderly adults perceived digital materials as less readable and less pleasant to read (Kretzschmar et al., 2013). Similar differences in attitude and actual reading experience in elderly adults was found by Hou, Wu and Harrell (2017) who also assessed reading comprehension when using mobile devices and the effects of cognitive maps formation on reading performance. While even in cases when development of cognitive map was difficult there were no effects on reading comprehension; however, a subjective attitude to ICT, technophobia, provided a significant impact on reading experience. Research participants with high levels of technophobia spent much more time on reading texts and experienced feelings of discomfort (Hou et al., 2017). The familiarity with digital technologies and habits of using them affected the acceptance of e-books by elderly people, as was demonstrated by Canadian researchers (Quan-Haase, Martin and Shreurs, 2016).

There is also a group of researchers interested in the relation between digital inequality and digital or online reading. Research in different countries has shown that that age, sex, and family annual income were significant predictors of digital reading preferences, propensity and perceptions (Bergström and Höglund, 2014; Seok and DaCosta, 2017). The results of digital reading assessment (Thomson and De Bortoli, 2012) in Australia has included searching for texts and navigation in the digital text as well as usual indicators of reading. It revealed the same gap between reading and digital reading between male and female students (males performing significantly lower than females). There was also variation by social group: those attending government schools, those in remote areas, indigenous students and students from low socioeconomic and immigrant backgrounds, produced weaker results. The same variation was found in print reading assessments (Thomson and De Bortoli, 2012). However, male students have been stronger in digital skills, such as navigation and searching. The influence of socio-economic factors on digital reading literacy was confirmed for the Southern Taiwan elementary school children (Chen, 2017).

Henry (2007) conducted an extensive study of online reading, comparing the reading comprehension of the urban middle school students and their teachers from economically disadvantaged districts of Connecticut with those from economically privileged districts. Her results show that both students and teachers from economically disadvantaged districts had lower online reading comprehension than those from economically privileged districts. The online reading comprehension scores could be reliably predicted from the levels of Internet access (the first level of digital divide) and Internet use skills (the second level of digital divide). These actually create an online reading comprehension gap between both groups of students and teachers (Henry, 2007). Leu et al. (2015) obtained similar results – the lower level of online reading comprehension was found in a school of an economically disadvantaged region and such results were related to lower level of Internet access and use at school. Later, Hutchison and Henry (2010) conducted a survey and assessment, measuring seventh grade students in 12 high dropout-risk schools. They found differences in Internet access among different students, and in frequency of use and skills in the high drop-out risk group and among boys and girls (the latter doing much better than boys). They stated: ‘Even if all students have Internet access at home, not all students have means of learning new and advanced skills with technology, especially, those skills needed to navigate the multimodal texts on the Internet’ (Hutchison and Henry, 2010, p. 73). Thus, it is necessary to devise ‘a mechanism for teaching high level Internet reading comprehension skills’ (Ibid.).

Current research also shows that low income, elderly age, lower level of education, disability and other socio-demographic characteristics significantly influence the digital reading preferences. For instance, research has shown that people with lower income and education levels are not likely to use the Internet for information and news reading, and self-development reading activities (van Deursen and van Dijk, 2014; Nguyen and Western, 2007; Tsetsi and Rains, 2017). In addition, Tsetsi and Rains (2017) extended these findings to cover disadvantaged racial minority groups, while van Deursen and van Dijk (2014) found the same trend is valid for disabled people.

Results: the impact of digital reading interventions to social and digital inclusion

Research about success or failure of digital reading to diminish digital or social inequality is rare. The literature that we have found mainly relates to the impact of digital reading on literacy acquisition.

McNab (2016) explored how parents in low socio-economic status schools were using digital books on iPad tablet computers with their children and the effects of reading digital texts on young children’s early literacy development. The study was conducted with families from low socio-economic areas of Tasmania, in three stages. The first step was to collect baseline data identifying ownership of digital reading devices and reading practices in families. The first intervention provided digital books on iPads for families from one primary school (with a comparison group from another primary school). The second intervention provided not only tablet computers and e-books, but also instruction on digital and dialogical reading and an opportunity to exchange knowledge with researchers. Intervention one showed that both groups of children (reading on iPads and in print) showed similar and significant achievements, while intervention two demonstrated significant gains by children in receptive vocabulary, expressive vocabulary, phonological abilities and concepts about print. In all cases, standard literacy tests and a receptive vocabulary instrument were used. Thus, the researcher demonstrated that digital books do not advantage or disadvantage children’s reading on their own and have a place in early reading development. They may serve as a beneficial tool for knowledgeable parents, who understand digital reading tools, and, even more, their own roles in this development. There was no comparison of the examined families with the families from high socio-economic areas (McNab, 2016; McNab and Fielding-Barnsley, 2013).

Korat and Shamir (2008) studied 149 children in kindergartens coming from low social- economic status and middle social economic status groups in Tel Aviv. They tested the development of word meanings, word recognition, and phonological awareness of children before and after interventions with a specially designed e-book incorporating functions important for all three tested areas. The results proved that children from both low and middle social economic status communities showed improvement, especially, in word meaning skills. Emergent literacy levels of the children from low status groups improved relatively more than those of the children from middle status groups in word recognition and sub-syllabic segmentation. This significant progress in emergent literacy levels of the children from the lower status communities is very important, as such children started with lower initial skills than children in higher status groups (Korat and Shamir, 2008). It proves that suitable educational software and specifically developed e-books can close the gap in reading and digital device skills.

Another interesting experiment, led by a renowned reading researcher, Wolf, was set up for a project, involving researchers from Tuft University and the MIT. The project at large-scale improvement in literacy and reading skills by using digital technologies in so-far illiterate communities that lacked pre-schools. The first stage, involving planting tablet computers with pre-selected apps and texts in two remote and isolated villages in Ethiopia (Wolf et al., 2012) was successful: in a year, forty children, who had never seen any written text in any form have found out how to use the tablets, learned the alphabet and acquired other skills required for reading, and selected the most helpful applications. This success opens the possibilities for further application of digital technology to introduce literacy and develop reading habits around the world and to disadvantaged groups in developed countries. (Wolf, Gottwald, Breazeal, Galyean and Morris, 2017). Similar educational experiments with incredible results, focused on slum children in India, known as hole in the wall, were performed by Mitra to observe independent development of computer literacy skills (Mitra, 2003). Children were able to gain computer skills independently, but also demonstrated learning new words in English and started reading the text in the language that they did not know previously (Mitra, 2003). There are initiatives seeking to diminish the influences of the social and economic backgrounds on learning to read and use digital media. The project and the book by Guernsey and Levine (2015) Tap, click, read targets low-income families with young children and helps adults to guide the children through a variety of digital media to acquire literacy and required reading skills. However, in this case, the assessment of success is missing.

Apart from these educational projects, we have also found some publications showing evidence that digital reading devices and e-books can increase effectiveness of communication, reading satisfaction, and general well-being of people with disabilities. Schneps et al. (2013) conducted an experiment showing the advantage of reading a specially configured text on a small device for dyslexic readers who showed increased speed and comprehension in comparison with paper-based texts. iPads with educational games and stories proved useful in enhancing social skills of hearing-impaired children from low-income families in comparison with those who had no access to iPads. The Child’s Social Interaction Scale (CSIS) was used to measure their social interaction skills before and after the intervention (Bahatheg, 2015).

Discussion: the impact of digital reading to reducing digital divide

The explored interventions show that there is an organic link between the elements of two theories, namely, the social cognitive theory and the levels of digital divide. Table 2 shows the elements and items of digital divide that fit under the categories of the social cognitive theory and help understanding the area of intervention for reducing the digital inequality. The resulting conceptual framework shows how particular levels of digital divide are related to environmental pressures, personal attitudes and how they result in specific behaviour.

| DIGITAL DIVIDE | ENVIRONMENT | PERSONAL ATTITUDES | BEHAVIOUR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Social pressure or support Mediation (McNab, 2016) Economic pressure (Henry, 2007) Resources and services: critical mass (Neumann and Celano, 2001) |

Relevance of resources Perceived relevance/benefit Perceived ease of use Perceived necessity Perceived losses (Kretzschmar et al., 2013) |

Use avoidance (Kretzschmar et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2017) Quick adoption (Wolf et al., 2012) |

| Access | Home equipment Work equipment Public spaces/equipment Possibility of access (crowd, time) Economic affordability (Union et al., 2015) Reading materials available (Neumann and Celano, 2001; Legge, 2016) |

Reluctance to use Technophobia (Hou et al., 2017) Intention to use (Hutchison and Henry, 2010) |

When and where digital technologies are used When and where reading materials are accessed Control over resources (Neuman et al., 2017; Union at al., 2015) |

| Skills | Training possibilities Acquired skills (Henry, 2007; Thomson and Bortoli, 2012; Leu et al., 2015; Wolf et al., 2012) |

Information literacy Computer and Internet skills Reading skills (Hutchison and Henry, 2010) |

How skills are trained Reading habits and preferences (Wolf et al., 2017; Bahatheg, 2015) |

| Usage/Benefits | Social environments and known (learned) models of usage/benefits (Hutchison and Henry, 2010; van Deursen and van Dijk, 2014; Tsetsi and Rains, 2017) |

Usage preferences (van Deursen and van Dijk, 2014; Nguyen and Western, 2007; Tsetsi and Rains, 2017) Perceived benefits: Economic/Financial Personal, Social, Cultural (BOP Consulting, 2015) |

What is used and read What aims are pursued with activities (Schneps et al., 2013; van Deursen and van Dijk, 2014; Nguyen and Western, 2007; Tsetsi and Rains, 2017) |

| GENERAL | Demographic variables, social inclusion/exclusion measures, health, family situation, etc. | ||

In accordance with van Dijk model of digital divide and Bandura's social cognitive theory, demographic variables had a profound horizontal impact on social, and consequently, different levels of digital exclusion (see Table 1). These covered low income, age and disability, in some cases racial differences. Often complex relations between inequalities were observed. It was also obvious that each inequality factor generated different exclusion effects on a disadvantaged individuals and groups.

Low income was an often-mentioned factor of social inequality and, consequently, digital exclusion of various social groups. It was obvious in research of low-income families and students from economically disadvantaged regions (Leu et al., 2015; Henry, 2007). Importantly, low income in these researches also influenced lower level of education mediated by the choice of educational establishments delivering lower level educational services. In turn, it resulted in limited availability and use of ICT in schools that mediated low general and digital reading comprehension levels. This research exhibited the complex nature and interplay of several social and digital exclusion factors. (Table 2: Environment/Access quadrant).

The second important demographic factor of social and, consequently, digital exclusion covered personal features and abilities, where age (Quan-Haase et al., 2016; Hou et al., 2017) and disability (Legge, 2016; Schneps et al., 2013; Bahatheg, 2015) were common exclusion factors. The lack of access to means addressing special needs resulted in low level of general literacy in children with autism and hearing impairments. With the increase of age much slower adoption of digital reading technologies was observed. Importantly, different personal characteristics produced different types of digital exclusion. In case of disabilities the lack of physical access to digital assistive technologies and accessible content resulted in low literacy level. While in case of elderly people, personal attitudes as, technophobia (Hou et al., 2017) came into play as an important inhibitor of motivation to use digital reading tools (Table 2: Environment/Motivation/Skills; Personal attitudes/Access/Skills; Behaviour/Motivation quadrants).

The personal attitudes depend on the pressures and support coming from the environment and help to acquire digital and literacy skills that may lead to changing intentions and actual use of digital technologies, thus diminishing digital exclusion (Hutchison and Henry, 2010). So, social environment and collaboration could become an important resource for further appropriation of digital learning technologies and deriving use from them. These features affect motivation and help to increase literacy skills in general (Wolf et al., 2017) (Table 2: Environment/Usage; Personal Attitudes/Motivation/Usage; Behaviour/Access/Skills/Usage quadrants).

As model shows, environment, personal attitudes and demographic features produce certain patterns of digital reading behaviour. With change of specific variables in digital reading interventions these patterns could be changed. Thus, all the elements of social cognitive theory, environment, personal attitudes and behaviour are in close correlation with the levels of digital divide. They interact and create mutual interdependence within social contexts, in which digital technologies and digital publications are deployed.

Conclusion

The conceptual framework developed in this paper is useful for understanding the whole chain of inter-related factors that either increase or reduce digital exclusion. This feature of the framework has a practical value because it could be helpful in design of practical digital (in this particular case, digital reading) interventions to reduce digital and social exclusion.

The literature review has shown that digital reading interventions proved to be particularly effective in increasing literacy skills of the most illiterate communities (McNab, 2016; Korat and Shamir, 2008; Wolf et al., 2012). The most significant achievements were observed in the lowest literacy groups, while some groups with some literacy skills in place did not demonstrate similar achievement levels (Korat and Shamir, 2008). While the most dramatic change was observed in completely illiterate communities that gained general literacy skills by digital reading practice without any help (Wolf et al., 2012). With reference to similar experiment to educate computer skills of illiterate Indian children with minimum interference by Mitra (2003) this gives a promise in overcoming social and digital exclusion on the literacy level.

Much less knowledge and research findings were accumulated about the role of digital reading in reducing inequalities in making benefits of using digital technologies. The research clearly shows that socio-demographic variables influence low levels of adoption and unproductive preferences in digital reading (van Deursen and van Dijk, 2014; Nguyen and Western, 2007; Tsetsi and Rains, 2017); however, there have been no attempts to check, if purposefully designed digital reading interventions could change this behaviour and attitudes. The digital reading research has extended the concept of reading into the area of device manipulation, navigation within the text and searching of digital texts that brings it closer to information seeking and digital literacy issues.

To summarise the literature review’s insights, several implications for research design of digital reading intervention and measuring its impact should be listed:

- Different factors and their specific influence on digital and social exclusion should be considered in various disadvantaged groups. For instance, technophobia is an important factor that inhibits motivation in digital reading.

- Digital reading interventions are successful in increasing digital literacy and general literacy skills. The most significant achievement is in the groups with the lowest or absent literacy skills. It may mean that disadvantaged groups with moderate literacy levels may need different digital reading interventions to reach a breakthrough.

- There is little relevant research addressing the third level of digital divide (except, van Deursen, Helsper, Eynon and van Dijk, 2017, which is not related to digital reading) and, consequently, social inclusion. Researchers have not yet considered the effect of digital reading interventions to broadening the understanding of ICT benefits for personal well- being, studies or work and turning to novel practices of ICT use was located.

About the authors

Zinaida Manžuch, Associate Professor, doctor, at the Digital Media Lab, Faculty of Communication, VilniusUniversity, Saulėtekis ave. 9, Vilnius, Lithuania. She received her PhD from Vilnius University and her research interests are in the areas of strategic management of cultural heritage digitization, strategic management of libraries and information services, communication of cultural content in the digital age, library management. She can be contacted at Zinaida.Manzuch@mb.vu.lt

Elena Macevičiūtė, Professor, habil.dr. at the Digital Media Lab, Faculty of Communication, Vilnius University, Saulėtekis ave. 9, Vilnius, Lithuania, and Swedish School of Library and Information Science, University of Borås, Allegatan 1, Borås, Sweden. She received her PhD from Moscow State Art and Culture University and her research interests are in the areas of organizational information and communication, digital publishing and reading, digital libraries’ and information management. She can be contacted at elena.maceviciute@gmail.com.

References

- Ackerman, R. & Goldsmith, M. (2011). Metacognitive regulation of text learning: on screen versus on paper. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17(1), 18–32.

- Bahatheg, R.O. (2015). iPads enhance social interaction skills among hearing-impaired children of low income families in Saudi Arabia. International Education Studies, 8(12), 167-175.

- Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. Northbrook, IL: General Learning Corporation.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewoods Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Baron, N.S., Calixte, R. & Havewala, M. (2017). The persistence of print among university students: an exploratory study. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 590-604.

- Bergström, A. & Höglund, L. (2014). A national survey of early adopters of e-book reading in Sweden. Information Research, 19(2), paper 621. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-2/paper621.html#.W5Nj--QnY2 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73POrEIEJ)

- BOP Consulting (2015). Literature review: the impact of reading for pleasure and enjoyment. London: The Reading Agency. Retrieved from https://readingagency.org.uk/news/The%20Impact%20of%20Reading%20for%20Pleasure%20and%20Empowerment.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74deYrBbi)

- Burgess, S.R., Hecht, S.A. & Lonigan, C.J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: a one-year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(4), 408-426.

- Carillo, K.D. (2010). Social cognitive theory in IS research – literature review, criticism, and research agenda. In: S.K. Prasad, H.M. Vin, S. Sahni, M.P. Jaiswal & B. Thipakorn (Eds.), Information systems, technology and management. ICISTM 2010 (pp. 20-31). Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer (Communications in Computer and Information Science, 54).

- Chen, G.C.W., Chang, T.-W., Zheng, X. & Huang, R. (2014). A comparison of reading comprehension across paper, computer screens, and tablets. Does tablet familiarity matter? Journal of Computers in Education, 1(2-3), 213-225.

- Chen, S.-F. (2017). Modeling the influences of upper-elementary school students’ digital reading literacy, socioeconomic factors, and self-regulated learning strategies. Research in Science & Technological Education, 35(3), 330-348.

- Clark, C. & Akerman, R. (2006). Social inclusion and reading: an exploration. London: National Literacy Trust. Retrieved from https://literacytrust.org.uk/research-services/research-reports/social-inclusion-and-reading-exploration-2006/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74deiKyVR)

- Farinosi, M., Lim, C. & Roll, J. (2016). Book or screen, pen or keyboard? A cross-cultural sociological analysis of writing and reading habits basing on Germany, Italy and the UK. Telematics and Informatics, 33(2), 410-421.

- Gartner Inc. (2011). Gartner survey shows digital text consumption nearly equal to time spent reading printed paper text. Retrieved from http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/1673714 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PRPSD6w)

- Gerlach, J. & Buxmann, P. (2011). Investigating the acceptance of electronic books – the impact of haptic dissonance on innovation adoption. In Proceedings of European Conference in Information Systems - ECIS 2011, 141. Retrieved from http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/141 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PRkHqZX)

- Guernsey, L. & Levine, M.H. (2015). Tap, click, read. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley, Josey-Bass.

- Henry, L.A. (2007). Exploring new literacies pedagogy and online reading comprehension among middle school students and teachers: Issues of social equity or social exclusion? Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut, Storrs, USA.

- Hillesund, T. (2010). Digital reading spaces: how expert readers handle books, the Web and electronic paper. First Monday, 15(4-5). Retrieved form http://firstmonday.org/article/view/2762/2504 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PRyADBC).

- Hou, J., Wu, Y. & Harrell, E. (2017). Reading on paper and screen among senior adults: cognitive map and technophobia. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, paper 2225. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02225/full (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PV7EQtT).

- Hultgren, F. & Johansson, M. (2017). Stimulera läsintresse [Stimulate reading interest]. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved from https://larportalen.skolverket.se

- Hupfeld, A., Sellen, A., O’Hara, K. & Rodden, T. (2013). Leisure based reading and the place of e-books in everyday life. In P. Kotzé, G. Marsden, G. Lindgaard, J. Wesson & M. Winckler, (Eds.), 14th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (INTERACT), Sep 2013, Cape Town, South Africa, part II, (pp. 1-18). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Hutchison, A. & Henry, L.A. (2010). Internet use and online literacy among middle grade students at risk of dropping out of school. Middle Grades Research Journal, 5(2), 61-75.

- Jauss, H.R. (1982). Toward an aesthetic of reception. Trans. T. Bahti. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Juric, M. (2017). The role of the need for cognition in the university students’ reading behavior. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Zadar, Croatia, 20-23 September, 2016: Part 2. Information Research, 22(1), paper isic1620). Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/22-1/isic/isic1620.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6oGe1Algl)

- Kim, H.J. & Kim, J. (2013). Reading from an LCD monitor versus paper: teenagers’ reading performance. International Journal of Research Studies in Educational Technology (IJRSET), 2(1), 1–10.

- Korat, O. & Shamir, A. (2008). The educational electronic book as a tool for supporting children’s emergent literacy in low versus middle SES groups. Computers & Education, 50(1), 110–124.

- Kretzchmar, F., Pleimlinq, D., Hosemann, J., Füssel, S., Bornkessel-Schlesewsky, I. & Schlesewsky, M. (2013). Subjective impressions do not mirror online reading effort: concurrent EEG-eyetracking evidence from the reading of books and digital media. PLoS one, 8(2): e56178. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23405265 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PSk7X0D).

- Kurata, K, Ishita, E. & Miyata, Y. (2017). Print or digital? Reading behavior and preferences in Japan. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(4), 884–894.

- Legge, G.E. (2016). Reading digital with low vision. Visible Language, 50(2), 102-125.

- Leu, D.J., Forzani, E., Rhoads, C., Maykel, C., Kennedy, C. & Timbrell, N. (2015). The new literacies of online research and comprehension: rethinking the reading achievement gap. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(1), 37-59.

- Liu, Z. (2005). Reading behavior in the digital environment: changes in reading behavior over the past ten years. Journal of Documentation, 61(6), 700-712.

- McNab, K.F. (2016). Digital texts for shared reading: effects on early literacy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia.

- McNab, K. & Fielding-Barnsley, R. (2013). Digital texts, iPads, and families: an examination of families' shared reading behaviours. International Journal of Learning, 20(1), 53-62.

- Mangen, A. & Kuiken, D. (2014). Lost in an iPad: narrative engagement on paper and tablet. Scientific Study of Literature, 4(2), 150-177.

- Mangen, A., Walgermo, B.R. & Brønnick, K. (2013). Reading linear texts on paper vs. computer screens: effects on reading comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 58(1), 61–68.

- Margolin, S.J., Driscoll, C., Toland, M.J. & Kegler, J. (2013). E-readers, computer screens or paper: does reading comprehension change across media platforms? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(3), 512–519.

- Mitra, S. (2003). Minimally invasive education: a progress report on the “hall-in-the-wall” experience. British Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3), 367-371.

- Neumann, M.M., Finger, G. & Neumann, D.L. (2017). A conceptual framework for emerging digital literacy. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(4), 471-479.

- Neumann, S.B. & Celano, D. (2001). Access to print in low-income and middle-income communities: an ecological study of four neighborhoods. Reading Research Quaterly, 36(1), 8-26.

- Nguyen, A. & Western, M. (2007). Socio-structural correlates of online news and information adoption/use. Journal of Sociology, 43(2), 167-185.

- Quan-Haase, A., Martin, K. & Shreurs, K. (2016). Interviews with digital seniors: ICT use in the context of everyday life. Information, Communication & Society, 19(5), 691-707.

- Parsons, S. & Bynner, J. (2002). Basic skills and social exclusion: findings from a study of adults born in 1970. London: Basic Skills Agency.

- Picton, I. & Clark, C. (2015). The impact of ebooks on the reading motivation and reading skills of children and young people: a study of schools using RM books. Final report. London: National Literacy Trust.

- Ross, C. (2000). Finding without seeking: what readers say about the role of pleasure reading as a source of information. Australasian Public Libraries and Information Services, 13(2), 72-80.

- Schneps, M.H., Thomson, J.M., Chen, C., Sonnert, G. & Pomplun, M. (2013). E-readers are more effective than paper for some with dyslexia. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e75634. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24058697 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PT3xMN8)

- Schubert, F. & Becker, R. (2010). Social inequality of reading literacy: a longitudinal analysis with cross-sectional data of PIRLS 2001 and PISA 2000 utilizing the pair wise matching procedure. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28(1), 109-133.

- Seok, S. & DaCosta, B. (2017). Gender differences in teens’ digital propensity and perceptions and preferences with regard to digital and printed text. TechTrends, 61(2), 171-178.

- Stanovich, K.E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quaterly, 21(4), 360-406.

- Straub, E.T. (2009). Understanding technology adoption: theory and future directions for informal learning. Review of Educational Research, 79(2), 625-649.

- Tenopir, C., Volentine, R. & King, D.W. (2012). Article and book reading patterns of scholars: findings for publishers. Learned Publishing, 25(4), 279–291.

- Thomson, S. & De Bortoli, L. (2012). Preparing Australian students for the digital world : results from the PISA 2009 Digital Reading Literacy Assessment. Camberwell, Australia: ACER Press. Retrieved from http://research.acer.edu.au/ozpisa/10 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PTHTNAn).

- Tsetsi, E. & Rains, S A. (2017). Smartphone Internet access and use: extending the digital divide and usage gap. Mobile Media & Communication, 5(3), 239-255.

- Union, C.D., Walker Union, L. & Green, T.D. (2015). The use of eReaders in the classroom and at home to help third-grade students improve their reading and English Language Arts Standardized Test Scores. TechTrends, 59(5), 71–84.

- van Deursen, A.J.A.M., Helsper, E., Eynon, R. & van Dijk, J.A.G.M. (2017). The compoundness and sequentiality of digital inequality. International Journal of Communication, 11, 452-473. Retrieved form https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5739/1911 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PTWdLnD).

- van Deursen, A. J. & Van Dijk, J.A.G.M. (2014). The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. New Media & Society, 16(3), 507-526.

- van Dijk, J.A.G.M. (2005). The deepening divide, inequality in the information society. Thousand Oaks, CA, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- van Dijk, J.A.G.M. (2012). The evolution of the digital divide: the digital divide turns to inequality of skills and usage. In J. Bus, M. Crompton, M. Hildebrandt & G. Metakides (Eds.), Digital enlightenment yearbook (pp. 57-75). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Warschauer, M. (2002). Reconceptualizing the digital divide. First Monday, 7(1), paper 967. Retrieved from http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/967 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73PTw8NHD)

- Wolf, M., Gottwald, S., Breazeal, C., Galyean, T. & Morris, R. (2017). I hold your foot: lessons from the reading brain for addressing the challenge of global literacy. In A. Battro, P. Léna, M. Sánchez Sorondo & J. von Braun (Eds.), Children and sustainable development (pp. 225-238). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Wolf, M., Ullman-Shade, C. & Gottwald, S. (2012). The emerging, evolving reading brain in a digital culture: implications for new readers, children with reading difficulties, and children without schools. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 11(3), 230- 240.

- Zhang, Y. & Kudva, S. (2014). E-books versus print books: readers' choices and preferences across contexts. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(8), 1695–1706.