Modelling the information-seeking behaviour of international students in their use of social media in Malaysia

Sarah Bukhari, Suraya Hamid, Sri Devi Ravana, and Mohamad Taha Ijab.

Introduction. The understanding of the information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media is limited. Therefore, the purpose of this research is to model the information-seeking behaviour of international students when they use social media to find information.

Method. A mixed method approach was employed to collect data from the literature. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twenty international students of different demographic backgrounds and with eleven staff members who work with international students. Questionnaires were distributed to 205 international students from four universities in Malaysia.

Analysis. Using the literature review and empirical data, we propose a model of the information-seeking behaviour of international students who use social media, as validated and verified from the questionnaire.

Results. The information-seeking activities were identified as informal searching, deciding, interacting, following, verifying and saving. The sources were search engines, social media and face-to-face settings. However, social media are more dominant than search engines and face-to-face communication. The questionnaire validated the proposed model and demonstrated that demographic variables exert a significant effect on the information-seeking behaviour of international students as they use social media.

Conclusion. This research enhances the previous models of information-seeking behaviour by adding the role of social media and provides valuable insights for international students, universities and higher-education institutions.

Introduction

International students come from various countries and therefore from different backgrounds and cultures. Seeking information is one of the inevitable activities these students engage in when they study abroad (Yi, 2007). Ishimura and Bartlett (2014) pointed out that information needs and information-seeking behaviour among international and local students are different. However, there is limited research that identifies such needs (Baharak and Roselan, 2013; Kim, Sin and He, 2013; Malaklolunthu and Selan, 2011; Smith and Khawaja, 2011; Yoon and Chung, 2017).

The difficulty faced by international students in obtaining specific and relevant information whilst studying abroad may cause several issues, including mental problems such as emotional distress and difficult in adaptation, social functioning, and well-being in various aspects of social life (Liu, 2009). Such limitations could also affect the academic performance and ability of these students, including their experience accumulation, social connectedness and language ability. International students are normally unable to obtain the information they need from libraries, Google and the Web (Liu, 2009; Yoon and Chung, 2017). An emerging and relatively easy method for seeking specific information is accessing it through social media (Kim, Yoo-Lee and Sin, 2011). However, studies on the information-seeking behaviour of international students in the current setting (e.g., settlement abroad and academic process such as registration, student visa process, course information and so on are lacking (Liu and Winn, 2009; Natarajan, 2012; Spink and Cole, 2006; Yoon and Chung, 2017). Therefore, the limited investigation into the effects of social media on the information-seeking behaviour of international students must be addressed to fulfil their perceived needs (Baharak and Roselan, 2013; Hamid, Bukhari, Ravana, Norman and Ijab, 2016; Kim, Sin and Tsai, 2014; Malaklolunthu and Selan, 2011; Yoon and Chung, 2017).

Current research on information-seeking behaviour focuses on understanding how the Internet and social media have changed how students seek information. The scholarly libraries and the Web (e.g., Google search) are used to search for information through keywords. Despite this accessibility, these searches often result in large quantities of general information (Junyi and Min, 2013). By contrast, social media allows a person to build connections with different people and to use them as a source of information (Chui et al., 2012; Steinfield, Ellison, Lampe and Vitak, 2013; Xiong et al., 2018). According to Mackenzie (2005) a person on social media regards other people as information sources in the form of relationships, knowledge, communication behaviour, communication style and cognitive ability.

Wilson (2000) defines information-seeking behaviour as a consequence of a need perceived by an information user, who, in order to satisfy it, makes demands upon formal or informal information sources or services, resulting in either success or failure. Social media websites and applications enable users to create and share content (Penni, 2017). On social media, a person must connect with another person or join a certain group to obtain information (Quinn, 2016). However, connections among people (also called social capital) only provide a specific type of information, opinions, advice and recommendations (Jaidka, Khoo and Na, 2013; Khoo, 2014; Morrison, 2015; Steinfield, DiMicco, Ellison and Lampe, 2009). As the concept of information-seeking behaviour in social media is different from that of the Web, Google and other electronic databases, (Austin, Fisher Liu and Jin, 2012; Khoo, 2014; Schroeder, 2018), this research aims to answer the following research question.

RQ: How can a model of information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media be formulated and tested?

To answer this question, we employed a mixed method through the collection and analysis of extant literature, interviews and questionnaires. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents the literature review, which is followed by a discussion of the methods used in the research. Then follow the results, discussion and conclusion.Literature review of information-seeking behaviour research

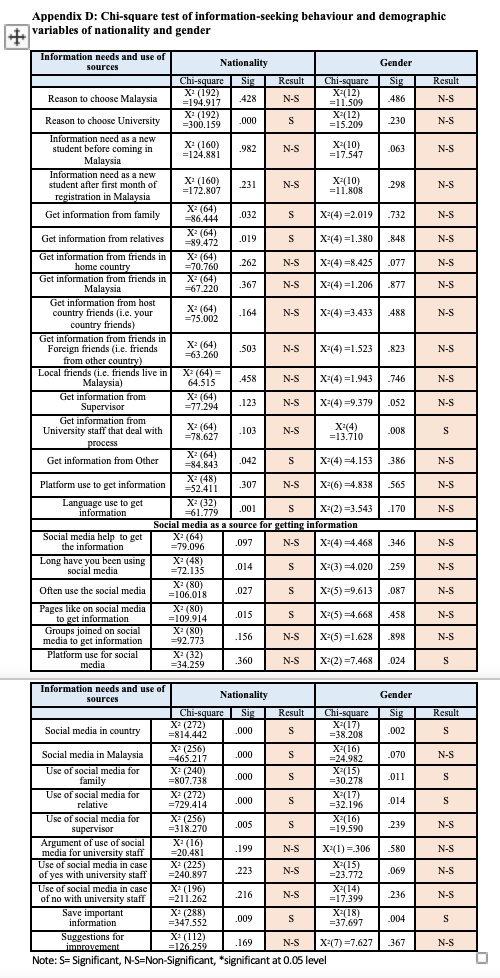

This literature review examines the current status of the research into the information-seeking behaviour of international students in the context of social media. The section starts with the information needs of international students and the information sources they use to seek information. Subsequently, we review extant work on the role of social media in supporting information-seeking behaviour. Lastly, we review the five popular information-seeking behaviour models. The summary of the literature review helps identify the research gap (see Figure 1).

In the last few decades, researchers in developed countries have conducted studies in different disciplines to identify the needs and information-seeking behaviour of scholars, students and professionals. However, limited research identifies the information needs and information-seeking behaviour of international students (Yoon and Chung, 2017). The available literature (e.g,. Alemu and Cordier, 2017; Hamid et al., 2016) identifies broad information needs and categorises the information needs of international students into academic, financial, socio-cultural, health and technology-related needs. Academic information requires dealing with issues such as academic adaptation, academic performance, financial problems, funds, admission processes and student insurance. Financial information includes work restriction in host countries, financial constraints, lack of part-time jobs, research support, scholarship and high tuition fees. Socio-cultural information deals with personal, social, religious and cultural adjustments, relationships with other students and teachers, food, lifestyle, loneliness, acculturation stress, friendship and interaction.

Health is another information need that international students encounter in a new environment (Hamid et al., 2016; Yoon and Chung, 2017; Smith and Khawaja, 2011). The health information needs of international students pertain to the weather, poor health services, difficulties with health insurance and challenges in understanding health information and sources. Technology is an important need of international students who seek information. In the past, libraries were the major source of information. However, they lacked the comprehensive information required by international students. With the advancement of technology in recent years, the trend of information seeking has changed from libraries to other platforms, such as Web search engines and social media. International students utilise search engines (e.g., Google) and electronic libraries. However, the amount of information yielded from such information sources is massive, thereby causing an information overload. Social media provides specific information through social connections. When international students connect with other people, they form a network where they solve most of their problems.

Previous studies of information-seeking behaviour are based on libraries, recorded literature and interpersonal contact (Wilson, 1999). However, the new media environment (e.g., the Internet and social media) is blurring such boundaries (Case, 2012). Accordingly, the authors in Alzougool, Chang, Gomes and Berry (2013); Fortin (2000); Rowlands et al. (2008); and Saumure (2010), conducted research on the information-seeking behaviour of students, professionals (Makri, Blandford and Cox, 2008) and scholars (Meho and Tibbo, 2003) using electronic legal resources. However, the information derived from the Web or Google is general and massive (Junyi and Min, 2013). Using social media, international students can connect with students, both local and international, and their institute. These connections help them overcome homesickness, learn about new cultures, solve problems, release stress and maintain their emotional stability. The main social media roles identified from the literature are social interaction, information source and education advocacy for international students. Social media are information sources used on a daily basis, and it provides different types of information about health, education, culture, institutions, teachers and students. In this way, social media have become a source for fulfilling the information needs of international students.

Dozens of models of information-seeking behaviour have been published over the past decades. However, only a few models have become widely popular. Bukhari, Hamid and Ravana (2016) employed the five most popular information-seeking behaviour models used in previous research (Case, 2012). Every model (other than Wilson's (1999), which is a general model) targets a specific audience (Figure 1). However, studies on the information-seeking behaviour of international students who use social media are limited, creating a gap in the literature. To seek information on social media, a person must perform certain actions. Previously, a person had to perform several specific activities to obtain information from libraries. Studies on the role of social media and information-seeking behaviour of international students exist; however, very few studies focus on the frequent merging of these two fields (Khoo, 2014; Schroeder, 2018). Therefore, such studies must be conducted to acquire knowledge about their information-seeking behaviour. Ellis's information-seeking behaviour model is the dominant model because it provides a useful design in terms of activities that users might want to accomplish through systems (Makri et al., 2008; Meho and Tibbo, 2003).

Figure 1: Summary of literature and the research gap

Research method

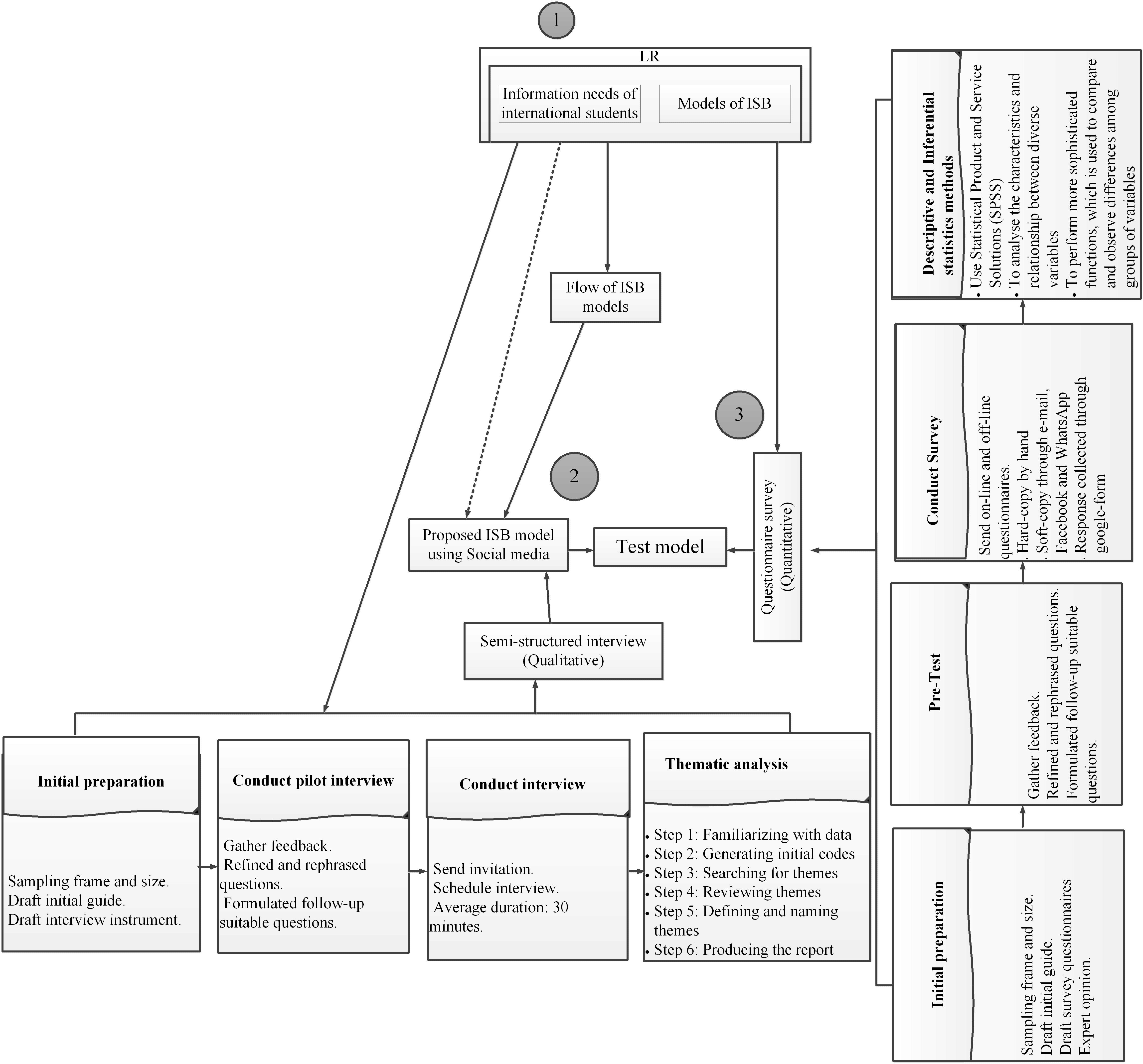

This research employed a mixed method to collect data (see Figure 2). Mixed-method is a combination of qualitative and quantitative techniques (Neuman, 2014; Williamson and Johanson, 2017). These two focuses on the strength and incorporate the findings of others (Connaway and Radford, 2016; Creswell, 2013). Two data collection instruments, interview and survey, are used. The data analysis is a step-by-step process to get the findings from the data. This research used a convenience sampling, which is a group of participants that are willing and easily accessible (Creswell, 2013; Williamson and Johanson, 2017). First, data were collected from semi-structured interviews to develop the proposed model. Secondly, a questionnaire survey was implemented to validate and verify the model. Semi-structured interviews were used in this research to identify problems and obtain an in-depth understanding of the process of information-seeking behaviour using social media. The literature scarcely addressed the phenomena explored in this research, so interviews were employed to further explore the views, experiences, beliefs and motivations of international students (Gill, Stewart, Treasure and Chadwick, 2008). This method helped attain highly personalised data from the respondents (Gray, 2003). The literature also inadequately explained information-seeking behaviour in the context of social media, so semi-structured interviews and a questionnaire were employed to explore the mechanisms of information-seeking behaviour using social media and to develop and test a model of this behaviour The next section explains information gathered about the participants, data collection and data analysis, and discusses the results.

The details of the method are as follows.

Literature review. The first step is to analyse the problem by reviewing previous work on social media use by international students to gain an understanding of their information-seeking behaviour. The literature review focused on the information needs of international students, their information sources and the role of social media in supporting information-seeking behaviour. Data collection was then conducted to confirm and support the findings of previous literature.

Semi-structured interviews. Semi-structured interviews were conducted from October 2016 to January 2017. Invitations to participate in the interviews were e-mailed and communicated face-to-face to twenty-five international students from the University of Malaya through convenience sampling. After one week, a follow up was done, and a series of interviews were performed with international students. A total of twenty participants agreed to be interviewed. The semi-structured interview questionnaires were divided into two parts. The first part dealt with the demographic information of the international students. The second part contained thirty open-ended questions that dealt with the steps, feelings and experiences related to the students' information-seeking behaviour on social media before and after coming to Malaysia. The data were collected until the saturation point was obtained and no new information could be gathered, as discussed in the literature review.

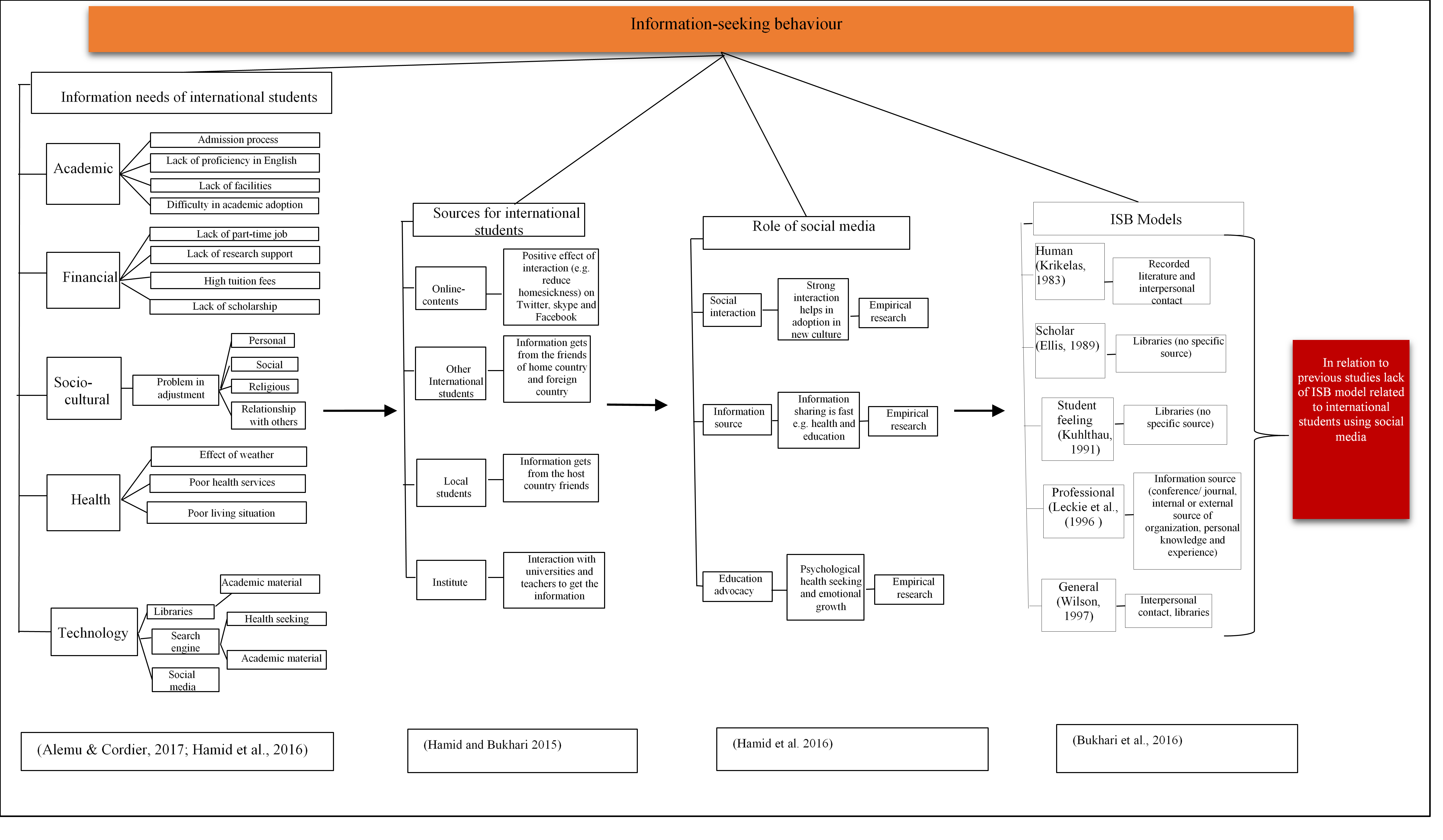

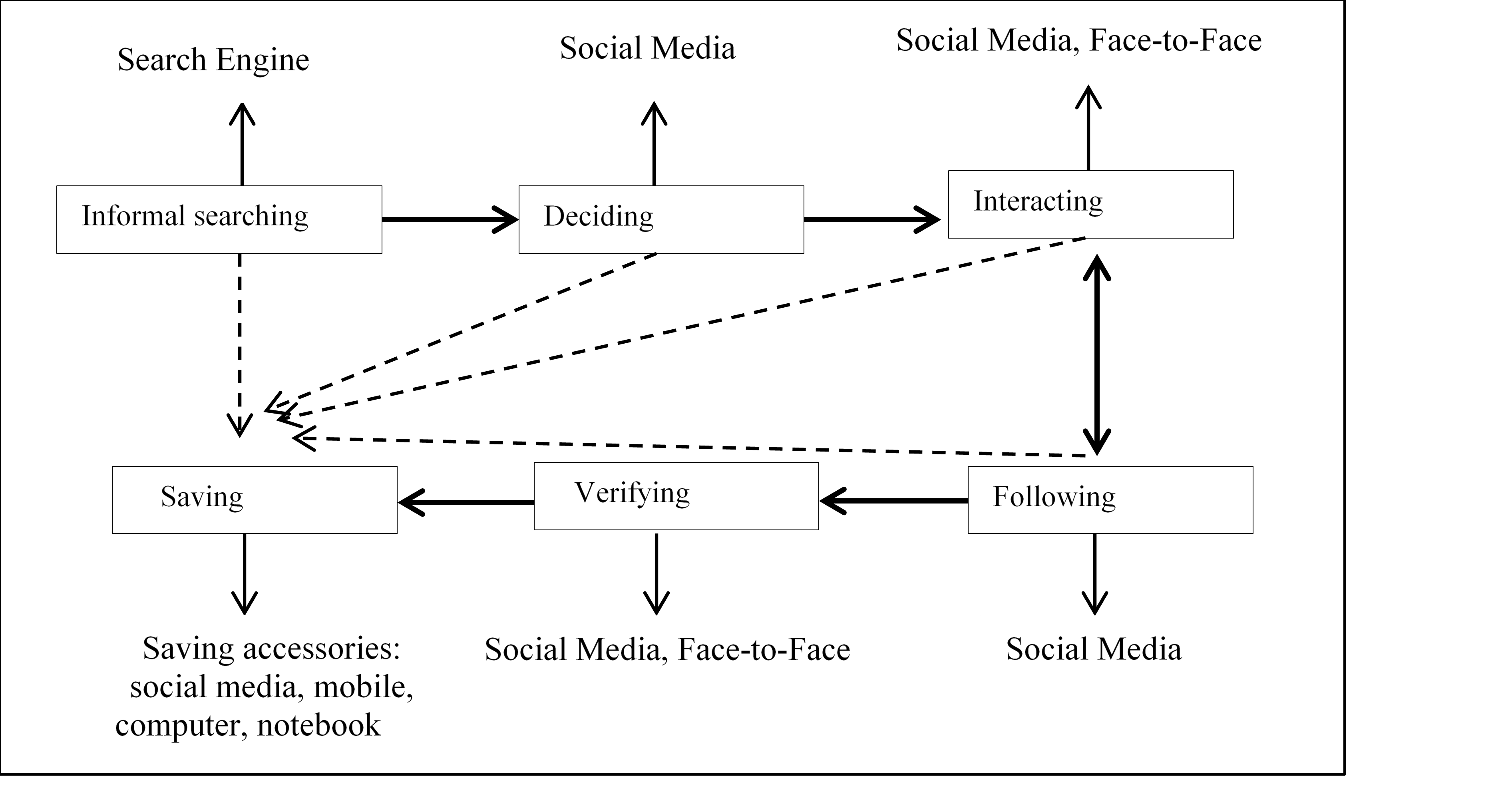

Proposed model. The findings of the interviews helped develop the model of information-seeking behaviour of international students as they use social media (Figure 3), which supports the literature review.

Test The proposed model was tested through validation and verification, which is discussed in the results and discussion section. Questionnaires were used to collect data from international students and administrative staff members who work with international students.

Survey. Closed and open questions were used in the questionnaires co. In addition, the questionnaires went through several stages of refinement and assessment by two experts from the Library Information Science Department and the Information System Department (University of Malaya). The questionnaires aimed to incorporate the main construct according to the proposed information-seeking behaviour model and provide sufficient details as required. The sample size was selected according to the guidelines provided by Collins, Onwuegbuzie and Jiao (2007), which specifies that the minimum number of participants when using the quantitative method for correlational and causal comparisons can be sixty-four to fifty-one for one-tailed tests and eighty-two to sixty-four for two-tailed tests.

The questionnaires were distributed in March 2017. To obtain a sample size greater than eighty-two, we waited for about four months for the online questionnaires to be completed by the participants. We began by contacting the participating international students from the four universities (Table 1) whose e-mail addresses were known or previously provided. Snowball sampling was also employed, as the participants were asked to forward the e-mail containing the link to the questionnaire to other individuals they believed could meet the qualifications for participation. The participants were recruited by e-mail and social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp. After collecting the data from the international students, an invitation letter was sent to the administrative staff from whom data were collected during the interviews (Appendix C). Then, convenience sampling was employed to obtain the response.

Figure 2: Research method and data analysis

Interviews

Twenty digital audio recordings from the international students and six more from the administrative staff were obtained from the interviews. The duration of each audio recording was approximately thirty minutes to one hour. In the case of the administrative staff (Table 3), the duration of each audio recording was thirty minutes. The transcripts were read multiple times and carefully evaluated to achieve a complete understanding of the interviews. On the basis of the literature review and existing models of information-seeking behaviour, 146 themes were identified during the first stage of data analysis. These themes included reasons for choosing countries and universities, types of information needs, sources used to obtain information, problems faced during information seeking and the role of social media in providing information. The themes were revised, connections were studied, and redundancies were removed, and were then coded into main themes. Transcripts were also analysed. Moreover, the themes were expanded, compared and altered (see Table 1). The steps for the thematic analysis were adopted from Braun and Clarke (2006) to deliver a specific and actual coding process as described in Appendix A.

Survey

The second data collection involved a survey of 205 international students from four universities in Malaysia. The survey aimed to validate the proposed model of information-seeking behaviour in the context of social media. To analyse the survey responses, we used descriptive and inferential statistics in determining the relationship between the variables. After collecting the feedback from the questionnaire, the data were downloaded from a Google Sheet and saved in Microsoft Excel to create a .CSV file to for later use in the SPSS statistical analysis package. SPSS was used to encode and manipulate the survey findings. For data analysis, a descriptive analysis was initially conducted, followed by an inferential analysis.

Descriptive analysis is a technique for analysing and summarising the characteristics and relationships between diverse variables (Williams and Monge, 2001). Inferential statistics involves generalising or making inferences from sample statistical population parameters. In the current work, we used the chi-squared test of independence to determine the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. The independent variables included the demographic variables, namely sex, level of study, age, nationality, faculty, current semester, full-time or part-time student, duration of stay in Malaysia and proficiency in written and oral English. The dependent variables included the types of information needs and peer selection (family, friends, relatives, supervisors and administrative staff) to obtain information and acquire a preference for using social media.

Results and discussion

Semi-structured interviews

The international students were from twelve countries: Pakistan, Thailand, Indonesia, Nigeria, Palestine, China, Iraq, India, Maqboza Kashmir, Algeria, Yemen and Iran. Appendix B summarises the detailed demographic information of the international students in the first data collection. After conducting the semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with the international students, a similar series interviews was conducted with the administrative staff of the different university departments who had experience dealing with international students in the University of Malaya. Appendix C presents the demographic information of the university staff.

On the basis of the analysis of the literature and the semi-structured interviews, we derived the following information-seeking behaviour constructs: informal searching, deciding, interacting, following, verifying and saving.

Based on the analysis of the results from the semi-structured interviews, Figure 3 presents the proposed model of information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media.

Figure 3: Proposed model of information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media

Survey

Frequency distributions, measures of central tendency and measures of variability that called for descriptive statistics were used in this research to make a meaningful representation of the data. A total of 205 respondents from four universities participated. The majority of the respondents were from the University of Malaya (43.90%); the rest were from the University Technology Malaysia (22.43%), the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (21.46%) and the International Islamic University (12.19%).

| University | Frequency | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| University of Malaya | 90 | 43.90 |

| University Technology Malaysia | 46 | 22.43 |

| Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia | 44 | 21.46 |

| International Islamic University Malaysia | 25 | 12.19 |

| Total | 205 | 100.0 |

Descriptive statistics were employed to calculate the frequency, percentage and mean to make a meaningful representation of the data. Nearly 61% of the respondents were female, and 39% were male. Most of the international students were bachelor (34.6%) and Ph.D. (34.6%) degree holders. The international students finishing their degrees (45.9%) were mostly female aged eighteen to twenty-five years. The largest category of international Ph.D. students in the current study were male (40.0%) aged twenty-six to thirty-three years. The countries from which the greatest number of students came were Pakistan (17.6%) and Bangladesh (12.7%). In total, the international students were from sixteen countries. In the 'other' option (open-ended question), international students were found to be from ten different countries. Iranian and Indonesian international students lived in Malaysia longer compared with the other international students. In addition, most of the international students studied computer science and information technology (30.2%). Nearly 50% of the international students were on their first and second year in their respective programmes, indicating that the international students were new. Exactly 97.1% of the international students were full-time students. Furthermore, the oral and written English proficiencies of the international students were deemed satisfactory. However, the male international students had better proficiency in English than their female counterparts.

Most of the international students preferred countries that offer cost-effective education (40.5%) and Muslim countries (37.6%). These results match those of Arambewela and Hall (2011), who found that cost of living, safety and security, linguistic proximity or distance and personal reasons, such as friends and family recommendations, are the considerations of international students when selecting a country for higher education. The top reasons for selecting a university were high rankings (66.8%) and suggestions from friends (17.6%). María, Sanchez and Cervino (2006) reported similar findings; they found that ranking, academic reputation, research quality and suggestions from family and friends affect the choice of university of international students. The findings of Borgatti and Cross (2003) are consistent with those of this research; that is, when a person acquires information on time from another person, information seeking is not costly. In addition, the international students utilised search engines (46.3%), social media (28.7%) and face-to-face (25%) platforms to obtain information. These results match those of Morris, Teevan and Panovich (2010), who found that people first use search engines for general information and use social media for opinions and recommendations. Caplan (2003) demonstrated that individuals prefer online over face-to-face social interactions. In the present research, the language used to search for information is English (67.3%), followed by a combination of English and the native language (29.3%) and then only the native language (3.4%). This result demonstrates that international students have good proficiency in English.

Female international students used social media more than their male counterparts did. These findings match those of Cha (2010), who discovered that females spend more time on social media than males. Most of the respondents used social media 'more than 6–20 times' a day (47%). In addition, the international students liked and joined an average of fifteen social media pages and groups to acquire information.

Most studies focused on students' social media preferences. An example is Madhusudhan (2012), who determined that the preferred social media of Delhi respondents are Facebook, Orkut, LinkedIn, Bharatstudent, Yahoo! Plus, Twitter, Zedge, Libibo, Yahoo! Buzz and Shtyle. Knight-Mccord et al. (2016) identified the preferred social media platforms of US college students as Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn and Pinterest. The current research determined the preferred social media platforms of international students in their home country, in Malaysia, for family, relatives, supervisors and university staff to gather information before and after coming to Malaysia.

The nationality of the international students determined their social media preference, as shown in Table 2 below.

| Students' country of origin | Social media | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face book | Insta- gram | Line | Tele- gram | Vika | We Chat | Whats App | N | |||

| Bangladesh | 26 | 21 | 26 | |||||||

| China | 15 | 22 | 25 | |||||||

| India | 7 | 12 | 12 | |||||||

| Indonesia | 13 | 14 | 18 | |||||||

| Iran | 13 | 10 | 15 | |||||||

| Iraq | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Maldives | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Nigeria | 11 | 11 | 12 | |||||||

| Pakistan | 29 | 33 | 36 | |||||||

| Palestine | 5 | 4 | 6 | |||||||

| Sri Lanka | 3 | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Sudan | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Thailand | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| U.K. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yemen | 5 | 6 | ||||||||

| Totals | 91 | 18 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 22 | 117 | 171 |

The research also showed that international students mostly save information through e-mails (61%), followed by mobile phones (48.3%), Dropbox accounts (39.0%) and computers (38.5%). By contrast, previous studies (Douglas et al., 2014) demonstrated different methods to save information, such as writing down in documents, keeping formal references and keeping notes along with references. According to the current research, international students used the latest technology to save important information. This procedure can help them access important information from anywhere.

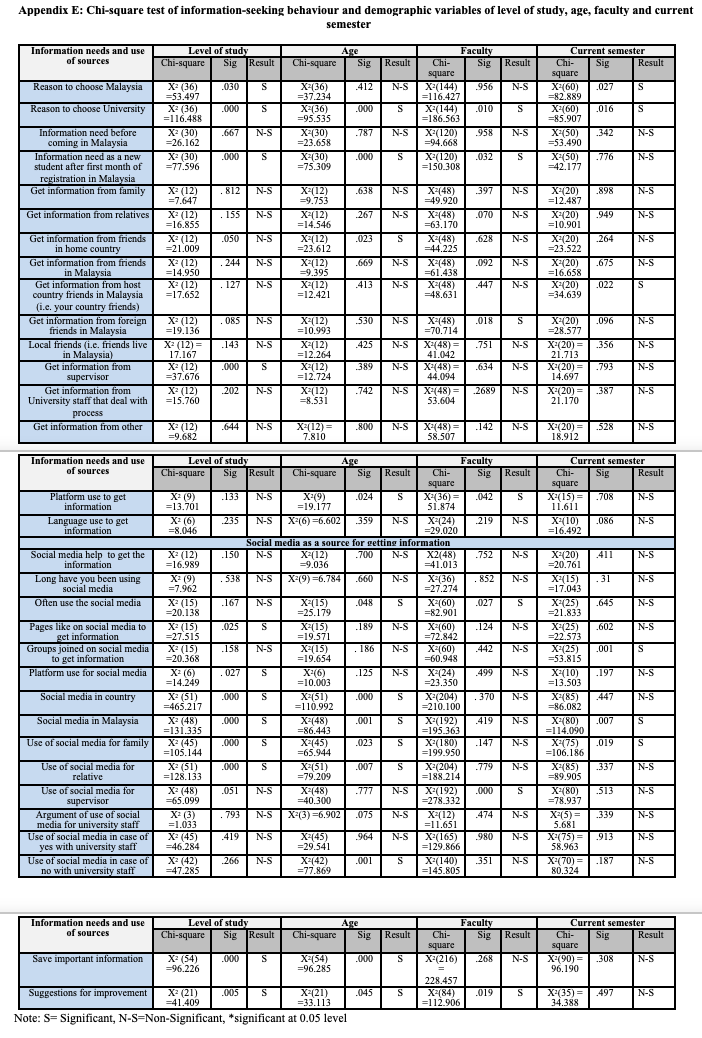

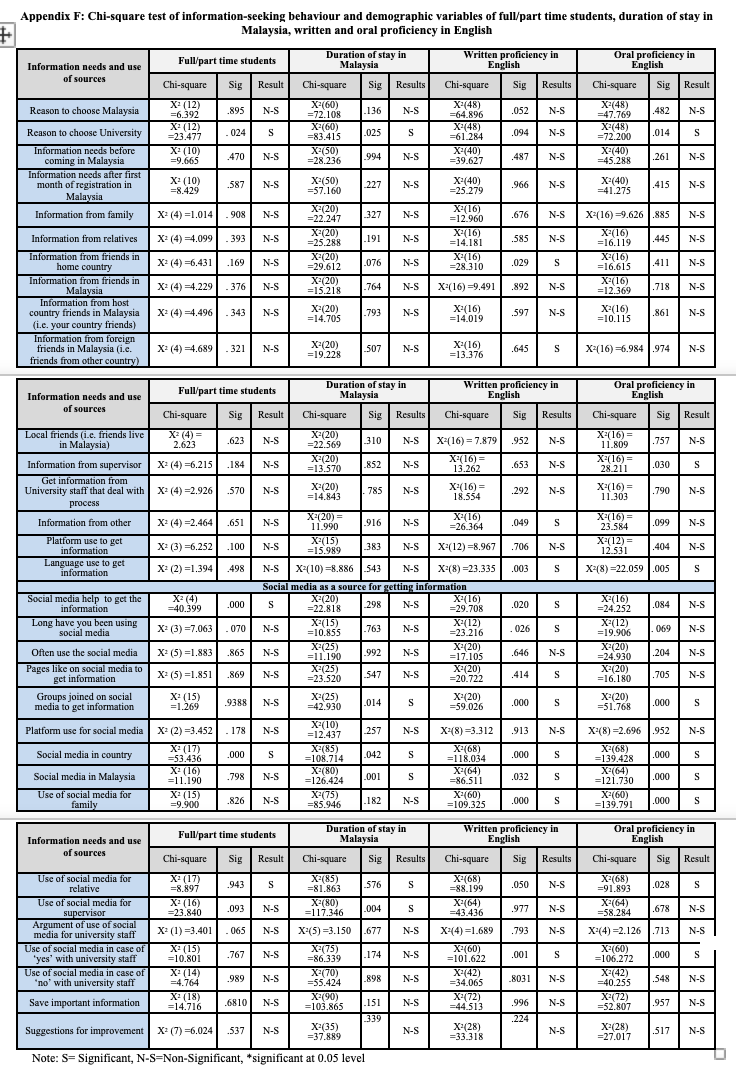

A chi-squared test was conducted to identify the relationship between demographic variables and information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media (Bukhari, 2018). The results of the test confirmed that demographic variables, especially nationality, level of study, age and proficiency in written English, exerted a significant effect on the information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media. as shown in Appendices D,E and F. These findings match those of Momoh and Folorunso (2013). The researchers Duru and Poyrazli (2007). Momoh and Folorunso (2013) and Poyrazli, Senel and Kavanaugh (2004); and Rao (2016) also found that demographic variables, such as sex, age, level of study, proficiency in English, marital status and nationality, affect the adjustment of overseas international students. After validating the model of information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media, the administrative staff at the visa unit and hostel who deal with international students verified this information. A 100% positive response was obtained from the administrative staff.

Final model

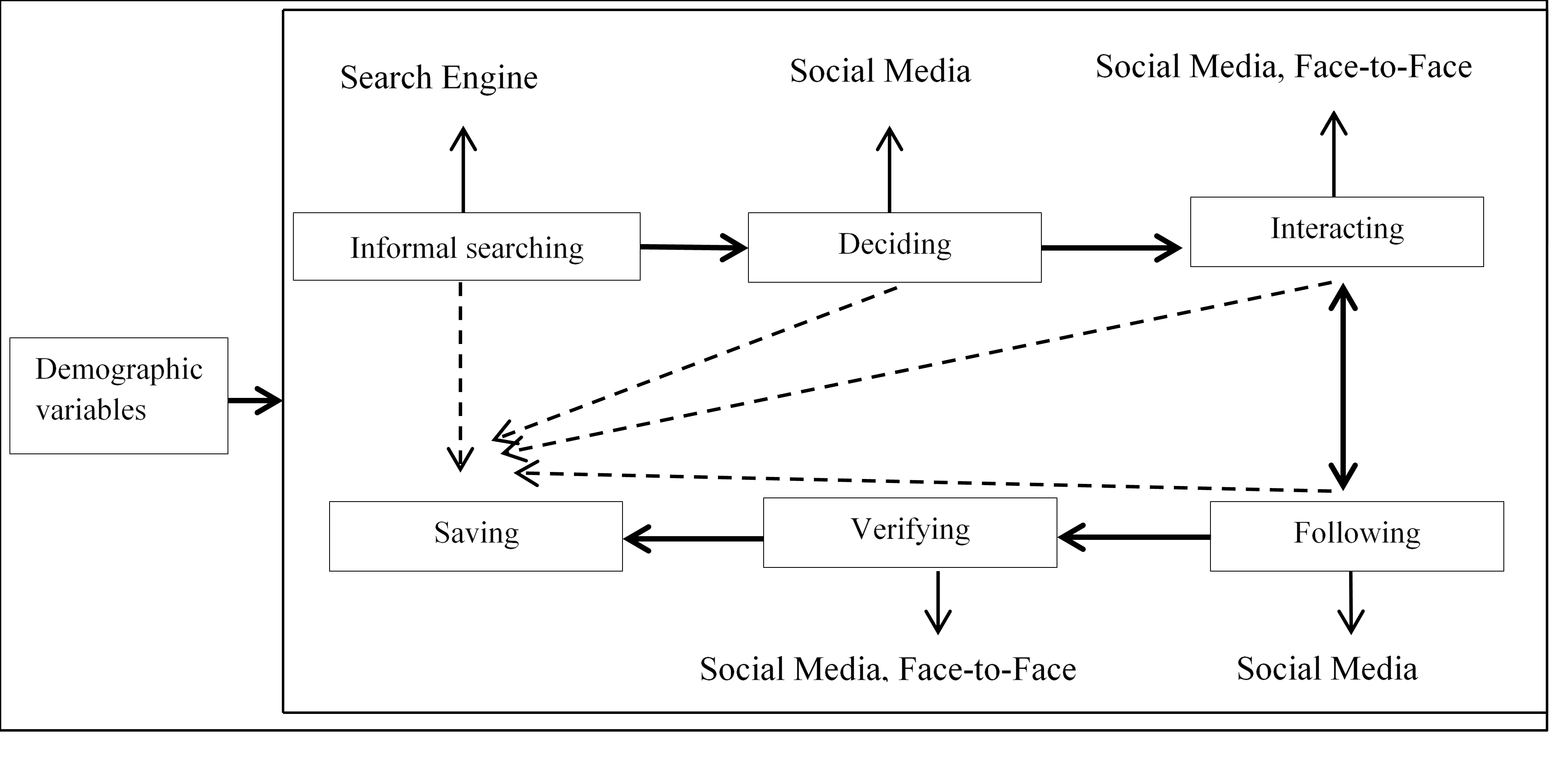

As results were obtained from the questionnaire, a few revisions to the proposed model were indicated (see Figure 4). The final model of the information-seeking behaviour of the international students using social media is composed of the following elements:

- Subject: International students

- Sources: Search engine, social media and face-to-face interactions

- Process: Information-seeking activities

- Informal searching: Using search engines to obtain information regarding the country and university.

- Deciding: Moving to social media owing to information overload from search engines, and seeking friends in social media.

- Interacting: Using social media and face-to-face platforms to interact with friends and university staff to obtain answers to queries.

- Following: 'Liking' pages and joining the groups of the universities and countries to obtain information.

- Saving: Saving important information for reuse.

- Demographic variables: Effects on information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media.

Figure 4: Information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media

In the originally proposed model (Figure 3), certain adjustments were made according to the questionnaire findings; for example, demographic variables were added, and save accessories were removed owing to the existing significant relationship.

Among the information-seeking behaviour models, the Ellis model is frequently used as the theoretical lens in model formulation because it provides a useful design in terms of activities that users might want to accomplish through the systems (Makri et al., 2008). However, the drawback of the Ellis model is that no specific information source is mentioned (Case, 2012). The current research fills the gap regarding the use of social media. The final model (Figure 4) was compared with the Ellis model and other models of information-seeking behaviour related to the role of social media and international students.

| Ellis (1989) | Information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media |

|---|---|

| Starting | Informal searching (Source: search engine) |

| Chaining, browsing, differentiation | Deciding (Source: social media) |

| Monitoring and Extracting | Interacting or following (Source: social media, face-to-face) |

| Verifying | Verifying (Source: social media, face-to-face) |

| Ending | Saving |

| No demographic variables available | Demographic variables |

The first information-seeking activity of the international students was the selection of a country and university for study. Several international students stated that they used search engines to select a country and university. They searched for living costs, ranking, requirements, visa process and so on, all of which comprised informal searching (Choo, Detlor and Turnbull, 2000; Choo and Marton, 2003). This information-seeking activity matches Ellis' first process called 'starting', which refers to the process of beginning the initial search for information. However, the Ellis model does not mention any specific source of information. In the current research, the international students used search engines in the initial step. The findings match those of Joseph and Joseph (2000), who mentioned that international students search for information on costs of living, location, availability of programmes, admission procedure and visa processing before seeking admission to overseas universities. Conversely, several of the international students in this current research mentioned their family, relatives, friends and home country supervisors as those who helped them select a country and university. The findings in Ojo and Yusofu (2013) supports the current research findings that friends and family play an important role in the selection of an overseas university. Mazzarol and Soutar (2002) used parents and relatives as a factor and determined the most important factor in the selection of a host country by international students. In addition, Chapman (1981) found that apart from family and friends, high school teachers of students also helped them select their preferred colleges. In the current research, home country supervisors helped in the selection of a host country and university. Hence, our research identified the possible sources of international students in the selection of a host country and university.

In the second information-seeking activity, the international students mentioned clearly that they were unable to acquire detailed and accurate information from search engines. They needed connections with people living abroad and from the universities where they want to enrol for ease of information acquisition. Accordingly, they used social media, especially Facebook, to search for people. This information-seeking activity matches Ellis's process of 'chaining, browsing and differentiation', which means that after obtaining initial information, scholars use references and citations to seek information and differentiate their sources. However, Ellis does not mention all the processes used by scholars because several processes can be iterative or skipped. In addition, the second activity matches the second information search process in Kuhlthau (1991) which is called 'selection', that is, identifying and choosing a general topic to seek information. The findings also match those of Morris et al. (2010), who found that for initial search tasks, people use search engines to obtain opinions or recommendations before shifting to social media.

After finding friends on Facebook and other social media platforms, the international students began interacting with new friends and asking questions as part of their third information-seeking activity. Moreover, they posted several queries on Facebook to obtain information. Before coming to Malaysia, they used social media because of its free and easy-to-use features. This step matches Ellis's stage called 'monitoring and extracting', where scholars follow a source and extract information according to their needs. The findings are also consistent with those of Taecharungroj (2013), who discovered that social media serves as an easy-to-use educational tool that improves constructive thinking and builds social relationships with media richness.

In the fourth information-seeking activity, the international students began following pages and joined the groups related to overseas universities and countries. The information-seeking activities of interacting and following are bi-directional. These findings match those of Garrett and Cutting (2012), who found that social media promotes the exchange of ideas and discussion among international students. Given that the rules for international students change annually, they must verify large amounts of information.

The students in this study explained that before coming to Malaysia, they used social media to verify information. After arriving in Malaysia, they occasionally interacted face-to-face with other international students and university staff to verify information. The element 'verifying' in this model matches the information-seeking behaviour model of Meho and Tibbo (2003) and Ellis's model (Ellis, Cox and Hall, 1993); 'verifying' means checking the accuracy of information. In all these information-seeking activities, the international students saved information in different forms, such as saving on mobile phones, saving on computers, e-mailing, bookmarking sites and saving on Dropbox for reuse. This step matches Ellis, Cox and Hall's stage called 'ending' which means the activity comes to an end in the form of paper. These findings also reaffirm those of Douglas et al. (2014), who found that students keep track of their information in different forms, such as writing it down in documents, keeping a formal reference and keeping notes. Furthermore, the international students in the current study stated that they used social media because of its low cost and ease of use in obtaining information. The international students with different demographic backgrounds used different types of social media. For example, Chinese, Thai and Iranian students mentioned that they never used WhatsApp. However, after arriving in Malaysia, they started using the app because everyone did and it helped them communicate easily with other international students.

Thus, the research findings confirmed that international students perform information-seeking activities, namely, informal searching, deciding, interacting, following, verifying and saving. During these activities, international students used search engines, social media and face-to-face platforms. However, compared with search engines and face-to-face platforms, social media plays an important role in obtaining information at any time and any place. This finding is especially true when the international students were in their respective home countries and they needed to verify the information regarding the requirements of the university. By contrast, the international students used search engines in their first step to obtain general information and used the face-to-face platforms only when meeting people was possible. Therefore, as compared with social media, seeking information in search engines and with face-to-face platforms is limited. By contrast, demographic variables exert a significant effect on the information-seeking behaviour of international students. These findings match those of Momoh and Folorunso (2013), who found that demographic variables exert a significant effect on information-seeking behaviour. The researchers in Duru and Poyrazli (2007); Momoh and Folorunso (2013); Poyrazli and Kavanaugh (2004) and Rao (2016) also found that demographic variables, such as sex, age, level of study, proficiency in English, marital status and nationality, affect the adjustment of overseas international students.

Conclusion

This empirical investigation enhances our understanding of the information-seeking behaviour of international students who use social media. The information-seeking behaviour model studies were conducted before the growth of the Internet and thus lacked specific connections to social media. The information needs and information-seeking behaviour of international students differ from those of local students. Previous theories and models mostly offer a generic model of information-seeking behaviour in the context of libraries. These theories and models fail to consider the information-seeking behaviour of international students who use social media.

The context of this research concerns the information-seeking behaviour of international students in Malaysia. The conceptual model was based on existing information-seeking behaviour models, and the main model used for the theoretical lens was Ellis's model. The information needs of international students were identified and the role of social media in supporting information-seeking behaviour was examined. Furthermore, useful research instruments methods were developed to investigate the applicability of several elements in existing information-seeking behaviour models to develop the proposed model. The proposed model includes information-seeking activities, such as informal searching, deciding, interacting, following, verifying and saving. To obtain information, international students use sources such as search engines, social media and face-to-face platforms. Moreover, this study provides another theoretical contribution by testing the proposed model and investigating the relationship between demographic variables and the information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media. By contrast, most information-seeking behaviour studies only used descriptive methods and failed to investigate this relationship (Shboul, 2016). Furthermore, previous studies only concentrated on investigating the relationship between information behaviour in other diverse disciplinary backgrounds, not with international students.

The detailed explanation of the information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media provides valuable information for planning and developing comprehensive services and sources for international students, universities and higher-education institutions. Educational institutions may be incapable of delivering effective services to international students without identifying their information needs. Information-seeking behaviour provides a detailed explanation of how international students obtain information and the sources they use to fulfil their information needs. In this case, social media plays an important role because of its low cost, easy availability and the provision of specific information in comparison with search engines and face-to-face interactions.

The experiences and evidence from the different demographic backgrounds of international students contribute to the enhancement of empirical research that can be beneficial in informing real-life practitioners. In addition, the collected data are a mixture of different cultures from different countries and will thus facilitate our understanding of the similarities and differences of information-seeking behaviour and the use of social media.

Other than the above implications, this research has a few limitations. The sample size for the interview was limited to twenty international students in the University of Malaya, and international students from other universities were excluded. However, useful data were generated from the questionnaire survey. The sample size of the questionnaire was limited to 205 international student respondents from four universities in Malaysia. Thus, the applicability of the research findings to other countries is not covered, although the model of information-seeking behaviour of international students using social media is a generalised model and therefore applicable in other countries. We will overcome this limitation in the future.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the University of Malaya and the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia under research grant RP044A-17HNE and RP005E-13ICT.

About the authors

Sarah Bukhari is an assistant professor at the Department of Computer Science, National Fertilizer Corporation Institute of Engineering and Technology, Khanewal Road, Multan, Pakistan. She received her PhD from the University of Malaya and her bachelor's degree from Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan. Sarah has published a number of academic papers in the areas of information systems, specifically social network analysis, data mining, information seeking behaviour and social media. She can be contacted at bukhari_sarah@nfciet.edu.pk

Suraya Hamid is a senior lecturer at the Department of Information Systems, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She obtained her bachelor's and master's degrees in information technology from the National University of Malaysia and her PhD from the Department of Computing and Information Systems, University of Melbourne, Australia. Suraya's research has been on social informatics, educational technology and data analytics and she can be contacted at suraya_hamid@um.edu.my

Sri Devi Ravana received her bachelor's in information technology from the National University of Malaysia in 2000, a master's in software engineering from the University of Malaya, Malaysia and her PhD from the university of Melbourne, Australia. Her research interests include information retrieval heuristics, text indexing, data analytics and data mining. She is currently a Senior Lecturer and the Head for the Department of Information Systems, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She can be contacted at sdevi@um.edu.my

Mohamad Taha Ijab is a research Fellow at the Institute of Visual Informatics, National University of Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor. He holds a PhD in Business Information Systems from RMIT University. His MSc (Computer Science) is from University of Malaya and a BIT (Information Systems) from Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. His research topics include green information systems, social media use in higher education and big data analytics. He can be contacted at taha@ukm.edu

References

- Alzougool, B., Chang, S., Gomes, C. & Berry, M. (2013). Finding their way around: international students' use of information sources. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 1(1), 43–49. Retrieved from http://www.joams.com/uploadfile/2013/0426/20130426024659212.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71hotDfcQ)

- Arambewela, R. & Hall, J. (2011). The role of personal values in enhancing student experience and satisfaction among international postgraduate students: an exploratory study. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 29, 1807–1815. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82047001.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74ddPXNAr)

- Austin, L., Fisher Liu, B. & Jin, Y. (2012). How audiences seek out crisis information: exploring the social-mediated crisis communication model. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(2), 188–207.

- Baharak, T. & Roselan, B. B. (2013). Challenges faced by international postgraduate students during their first year of studies. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(13), 138–145. Retrieved from http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_13_July_2013/17.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71hrpgJWL)

- Borgatti, S. P. & Cross, R. (2003). A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Management Science, 49(4), 432–445.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Bukhari, S. (2018). Modelling the information-seeking behaviour of the international students using social media. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Bukhari, S., Hamid, S. & Ravana, S. D. (2016). Merging the models of information seeking behaviour to generate the generic phases. In 2016 3rd International Conference on Information Retrieval and Knowledge Management, CAMP (pp. 125–130).

- Caplan, S. E. (2003). Preference for online social interaction: a theory of problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being. Communication Research, 30(6), 625–648.

- Case, D. (2012). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seekings, needs and behavior. (3rd. ed.) Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 3rd Edition.

- Cha, J. (2010). Factors affecting the frequency and amount of social networking site use: motivations, perceptions, and privacy concerns. First Monday, 15(12). Retrieved from http://www.ojphi.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2889/2685 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71kA8BqOR)

- Chapman, D. W. (1981). A model of student college choice. Journal of Higher Education, 52(5), 490–505.

- Choo, C. W., Detlor, B. & Turnbull, D. (2000). Information seeking on the web: an integrated model of browsing and searching. First Monday, 5(2). Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED438801.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71i4q8zFI)

- Choo, C. W. & Marton, C. (2003). Information seeking on the Web by women in IT professions. Internet Research, 13(4), 267–280.

- Chui, M., Manyika, J., Bughin, J., Dobbs, R., Roxburgh, C., Sarrazin, H., … Westergren, M. (2012). The social economy: unlocking value and productivity through social technologies. New York, NY: McKinsey Global Institute. Retrieved from https://mck.co/2DIMEDQ. (Unable to archive)

- Collins, K. M. T., Onwuegbuzie, A. J. & Jiao, Q. G. (2007). A mixed methods investigation of mixed methods sampling designs in social and health science research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 267–294.

- Connaway, L. S. & Radford, M. L. (2016). Research methods in library and information science. (6th ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Douglas, K. A., Rohan, C., Fosmire, M., Smith, C., Van Epps, A. & Purzer, S. (2014). "I just Google it": a qualitative study of information strategies in problem solving used by upper and lower level engineering students. In IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) Proceedings, October 22-24, Madrid, Spain, (pp. 1–6). New Yor, NY: IEEE.

- Duru, E. & Poyrazli, S. (2007). Personality dimensions, psychosocial-demographic variables, and English language competency in predicting level of acculturative stress among Turkish international students. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(1), 99–110.

- Ellis, D., Cox, D. & Hall, K. (1993). A comparison of the information seeking patterns of researchers in the physical and social sciences. Journal of Documentation, 49(4), 356–359.

- Fortin, M. G. (2000). Faculty use of the World Wide Web: Modeling information seeking behavior in a digital environment. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of North Texas, Denton, Texas, USA.

- Garrett, B. M. & Cutting, R. (2012). Using social media to promote international student partnerships. Nurse Education in Practice, 12(6), 340–5.

- Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E. & Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6), 291–295. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/bdj.2008.192.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jgPgxnE)

- Gray, S. M. (2003). Looking for Information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 91(2), 259.

- Hamid, S., Bukhari, S., Ravana, S. D., Norman, A. A. & Ijab, M. T. (2016). Role of social media in information-seeking behaviour of international students: a systematic literature review. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 68(5), 643–666.

- Ishimura, Y. & Bartlett, J. C. (2014). Are librarians equipped to teach international students? a survey of current practices and recommendations for training. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(3–4), 313–321.

- Jaidka, K., Khoo, C. S. G. & Na, J. (2013). Literature review writing: how information is selected and transformed. Aslib Proceedings, 65(3), 303–325.

- Joseph, M. & Joseph, B. (2000). Indonesian students' perceptions of choice criteria in the selection of a tertiary institution: strategic implications. International Journal of Educational Management, 14(1), 40–44.

- Junyi, L. & Min, Y. (2013). The keywords-based online information seeking behavior of tourists. Tourism Tribune, 28(10), 15–22.

- Khoo, C. S. G. (2014). Issues in information behaviour on social media. Libres, 24(2), 75–96. Retrieved from https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.ntu.edu.sg/dist/8/644/files/2015/03/LIBRESv24i2p75–96.Khoo_.2014.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jgi0isP)

- Kim, K. S., Sin, S-C. & Tsai, T-I. (2014). Individual differences in social media use for information seeking. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 40(2), 171–178.

- Kim, K.S., Sin, J.S-C. & He, Y. (2013). Information seeking through social media: impact of user characteristics on social media use. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 50(1), 1–4. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/meet.14505001155 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jh1uBNk)

- Kim, K., Yoo-Lee, E. & Sin, S.-C. (2011). Social media as information source: undergraduates' use and evaluation behavior. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 48(1), 1–3. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/meet.2011.14504801283 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jh8aWRh)

- Knight-Mccord, J., Cleary, D., Grant, N., Jumbo, S., Lacey, T., Livingston, T., … Emanuel, R. (2016). What social media sites do college students use most ? Journal of Undergraduate Ethnic Minority Psychology, 2(21), 21–26. Retrieved from http://billsproject.com/department/COMPUTER SCIENCE/topics/Knight-McCord_et-al_JUEMP_2016.pdf/Knight-McCord_et-al_JUEMP_2016.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jhDyWnZ)

- Kothari, C. (2004). Research methodology: methods and techniques. (2nd revised ed.). New Delhi, New Age International.

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user's perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361–371.

- Liu, G. & Winn, D. (2009). Chinese graduate students and the Canadian academic library: a user study at the university of Windsor. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 35(6), 565–573.

- Liu, M. (2009). Addressing the mental health problems of Chinese international college students in the United States. Advances in Social Work, 10(1), 69–86. Retrieved from https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/advancesinsocialwork/article/view/164 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jhnD83B)

- Mackenzie, M. L. (2005). Managers look to the social network to seek information. Information Research, 10(2), paper 216. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/10-2/paper216.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jhveAWI)

- Madhusudhan, M. (2012). Use of social networking sites by research scholars of the University of Delhi: a study. International Information and Library Review, 44(2), 100–113.

- Makri, S., Blandford, A. & Cox, A. L. (2008). Investigating the information-seeking behaviour of academic lawyers: from Ellis's model to design. Information Processing & Management, 44(2), 613–634.

- Malaklolunthu, S. & Selan, P. S. (2011). Adjustment problems among international students in Malaysian private higher education institutions. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 833–837. Retrieved from http://eprints.um.edu.my/12870/1/Adjustment_problems_among_international_students.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71ji6jGvM)

- María, J., Sanchez, J. & Cervino, J. (2006). International students' decision-making process. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(2), 101–115.

- Mazzarol, T. & Soutar, G. N. (2002). “Push-pull” factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82–90.

- Meho, L. I. & Tibbo, H. R. (2003). Modeling the information-seeking behavior of social scientists: Ellis's study revisited. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(6), 570–587. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/asi.10244 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jiOuLKw)

- Momoh, M. & Folorunso, R. O. (2013). Effect of demographic variables on information seeking behaviour of company advertising strategies in North-Eastern Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 9(3), 46–51. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/download/32138071/F0934651.pdf (Unable to archive)

- Morris, M. R., Teevan, J. & Panovich, K. (2010). A comparison of information seeking using search engines and social networks. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM) (pp. 23–26). Retrieved from http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM10/paper/download/1518/1879 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jijQNRU)

- Morrison, R. (2015). Silver surfers search for gold: a study into the online information-seeking skills of those over fifty. Ageing International, 40(3), 300–310.

- Natarajan, M. (2012). Information seeking behaviour of students of management institutions in NCR of Delhi. Trends in Information Management, 8(2), 100–110. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1020.5499&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Unable to archive)

- Neuman, W. L. (2014). Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. (7th ed.). Essex, UK: Pearson education.

- Ojo, B. Y., & Yusofu, R. N. R. (2013). Edutourism: international student's decision making process in selecting a host university in Malaysia. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(30), 51–57. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1019.5995&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Unable to archive)

- Penni, J. (2017). The future of online social networks (osn): a measurement analysis using social media tools and application. Telematics and Informatics, 34(5), 498–517.

- Poyrazli, Senel & Kavanaugh, P. (2004). Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. Journal of College Counseling, 7(1), 73–82.

- Quinn, K. (2016). Contextual social capital: linking the contexts of social media use to its outcomes. Information, Communication & Society, 19(5), 582–600.

- Rao, P. (2016). The role of demographic factors of international students on teaching preferences: an empirical research from the United States. Journal for Multicultural Education, 10(1), 53–71.

- Rowlands, I., Nicholas, D., Williams, P., Huntington, P., Fieldhouse, M., Gunter, B., … Tenopir, C. (2008). The Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future. Aslib Proceedings, 60(4), 290–310.

- Saumure, K. (2010). Motivation and the information behaviours of online learning students: the case of a professionally-oriented graduate program. Department of Psychology and the School of Library and Information Studies, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.psych.ualberta.ca/~knoels/personal/Kim's%20publications/Kristie%20Saumure.pdf]

- Schroeder, R. (2018). Towards a theory of digital media. Information, Communication & Society, 21(3), 323–339.

- Shboul, M. K. (2016). Information needs and behaviour of humanities scholars in an ICT-enriched environment in Jordan. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Malayam, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(6), 699–713.

- Spink, A. & Cole, C. (2006). New directions in human information behavior. In Spink, A., & Cole, C. (Eds.), Multitasking and co-ordinating framework for human information behavior (pp. 137–154). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Steinfield, C., DiMicco, J. M., Ellison, N. B. & Lampe, C. (2009). Bowling online: social networking and social capital within the organization. In Proceedings of the fourth international conference on Communities and technologies (pp. 245-254). New York, NY: ACM.

- Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C. & Vitak, J. (2013). Online social network sites and the concept of social capital. In F.L. Lee, L. Leung, J.S. Qui, and D. Chu, (Eds.). Frontiers in New Media Research (pp. 115–131). London: Routledge.

- Taecharungroj, V. (2013). Homework on social media: benefits and outcomes of Facebook as a pedagogic tool. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 3(3), 258-263. Retrieved from http://www.ijeeee.org/Papers/235-ET1027.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jjVQbcj)

- Williams, F. & Monge, P. R. (2001). Reasoning with statistics: how to read quantitative research. (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Williamson, K., & Johanson, G. (2017). Research methods: information, systems, and contexts. (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Science.

- Wilson, T. D. (2000). Human information behavior. Informing Science, 3(2), 49–55. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2r5OaIG (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/71jjh5sqf)

- Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249–270.

- Xiong, X., Li, Y., Qiao, S., Han, N., Wu, Y., Peng, J. & Li, B. (2018). An emotional contagion model for heterogeneous social media with multiple behaviors. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 490, 185–202.

- Yi, Z. (2007). International student perceptions of information needs and use. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(6), 666–673.

- Yoon, J. & Chung, E. (2017). International students' information needs and seeking behaviours throughout the settlement stages. Libri, 67(2), 119–128.

How to cite this paper

Appendix A: Steps of thematic coding (Braun and Clarke, 2006)

| Steps | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Familiarisation with data | In the first step, the researcher read the data repeatedly to gain an in-depth understanding, establish points and identify patterns.To ensure accuracy the written transcript was checked against the recorded audio. A total of 146 themes were generated, along with their definitions. Recognised themes, such as information needs, information source and ISB, are based on the literature review. |

| 2 | Generating initial codes | In the second stage, formal coding was initiated by taking notes and ideas from the first step and written transcript. On a separate page, the name of each code was written with a brief description and later categorised into sub-themes. In addition, the relationships were considered among codes, themes and different levels of themes (e.g., main themes within sub-themes). |

| 3 | Searching for themes | Line-by-line analyses of the written manuscript were performed, and the process of the themes was determined. With the help of a highlighter pen, the potential patterns were identified, and notes were taken from the texts. This type of technique identified the patterns of themes through rich and complex narratives. In the semi-structured interviews, describing, associating and explaining the data in themes were necessary. Thus, from the initial coding, the main themes were formed. However, the sub-themes and other aspects were removed because of redundancy or irrelevance to ISB and social media. Once the themes were finalised, Step 3 was carried out to review the themes. The key points for the inventory sub-themes were developed. At this stage, the researcher systematically understood the data set and provided full attention to each data item. From the repetitive patterns in the data set, the motivating parts that fulfilled the research objectives were recognised. |

| 4 | Reviewing themes | Microsoft Word was used to save the records of the associated key quotations of each category that had been developed earlier. |

| 5 | Defining and naming themes | In the fifth step, the 146 categories (identified in the first step) were reduced to six main themes that matched the literature review discussed in Section 2. In each category, the IDs of the respondents with the selected quotes were included. The related literature and research questions were identified to support the themes. An example of the refined theme was provided, along with descriptions, quotations, respondents’ IDs, related questions and literature review. |

| 6 | Producing the report | After performing the data analysis and coding, the report was generated as explained. The proposed model of ISB in the context of social media was discussed. The findings of the interviews are presented in the Results section. For data analysis, the interpretation was informed according to the ISB models. The purpose was to obtain a rich and broad description of the research objective. |

Appendix B: Demographic characteristics and social media use of international students (interviews)

| ID | Age | Sex | Country | Highest education level | Department | Length of stay in Malaysia | Years using social media | Frequency of use | Most-used social media |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS-1 | 26 | Male | Pakistan | Master | Computer Science | 1 year 2 months | 4 years | Once a day | Facebook, WhatsApp, IMO |

| IS-2 | 26 | Female | Pakistan | PhD | Physics | 2 years | 10 years | Once or twice an hour | |

| IS-3 | 20 | Female | Thailand | Degree | Malay Studies | 2 years | 8 years | All the time | Facebook, WhatsApp, Line |

| IS-4 | 26 | Female | Indonesia | PhD | Photonics | 3 years | 2 years | Every hour | |

| IS-5 | 35 | Male | Pakistan | PhD | Computer Systems | 1 years 2 months | More than 10 years | 3 times a day | Facebook, Skype |

| IS-6 | 38 | Male | Nigeria | PhD | Library and Information Science | 10 months | More than 10 years | 2 or 3 hours a day | Facebook, WhatsApp |

| IS-7 | 30 | Female | Palestine | PhD | Computer Science | 4 months | 7 years | Every hour | Instagram, Facebook |

| IS-8 | 25–29 | Female | Pakistan | PhD | Islamic Studies | 3 years | 6 years | Once an hour | Instagram, Facebook |

| IS-9 | 26 | Female | China | Master | Language & Linguistics | 10 months | More than 10 years | 5 times an hour | WeChat, YouTube |

| IS-10 | 27 | Female | Iraq | Master | Language & Linguistics | 2 years | 10 years | 5 times an hour | |

| IS-11 | 24 | Female | China | Master | Economics and Administration | 2 years | More than 10 years | Once an hour | |

| IS-12 | 32 | Male | Pakistan | Master | Information Systems | 1 and half years | More than 10 years | Once or 2 times an hour | Facebook, Twitter |

| IS-13 | 32 | Female | Pakistan | PhD | Software Engineering | 2 years and 3 months | 10 years | Twice a day | Facebook, LinkedIn |

| IS-14 | 32 | Male | Nigeria | PhD | Computer Networks | 1 year | 10 years | Once an hour | |

| IS-15 | 27 | Female | India | PhD | Software Engineering | 2 years and 1 month | 5 years | Once an hour | Facebook, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, Research Gate |

| IS-16 | 29 | Male | Maqboza Kashmir | PhD | Computer Systems | 1 year | 9 years | 3 to 4 times a day | Facebook, LinkedIn |

| IS-17 | 25 | Male | Algeria | PhD | Artificial Intelligence | 3 years | More than 10 years | More than once an hour | Facebook, WeChat, WhatsApp, Viber, Vika, e-mail, QQ |

| IS-18 | 29 | Male | Yemen | PhD | Information Systems | 3 years | More than 10 years | Mostly at night , 3 or 4 times | Facebook, Twitter, Instagram |

| IS-19 | 36 | Male | Nigeria | Master | Computer Science | 1 and half years | 6 years | 3 times a day | Facebook, WhatsApp |

| IS-20 | 29 | Female | Iran | PhD | Computer Networks | 8 months | 5 to 6 years | Twice an hour | Telegram |

Appendix C:

| ID | Age | Sex | Position | Qualification | Department | Experience | Years of using social media | Frequency of use | Most-used social media |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-1 | 37 | Female | Senior Assistant | Master | ISC | 5 years | More than 10 years | After office hours | |

| S-2 | 32 | Female | Officer Assistant in Registration | Degree | ISC | 5 years | More than 7 years | 10 times an hour | |

| S-3 | 26 | Male | Project Officer | Degree | ISC | 5 years | 7 years | Once an hour | Facebook, WhatsApp |

| S-4 | 25 | Female | Clerk in Visa Unit | Diploma | ISC | 5 years | 4 years | 18 hours a day | WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook |

| S-5 | 37 | Male | Administrative Assistant | Secondary school | FSKTM | 5 years | 4 years | 2 hours a day | WhatsApp, Instagram |

| S-6 | 36 | Female | Administrative staff | Degree | Hostel | 10 years | More than 10 years | 3 times an hour | Facebook, E-mail |

| Note: S-1= first staff, ISC = International Student Centre, FSKTM = Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology | |||||||||