Structure to the unstructured - Guided Inquiry Design as a pedagogical practice for teaching inquiry and information literacy skills

Jannica Heinström and Eero Sormunen

Introduction. Guided Inquiry Design (GID) is a research-based pedagogical framework for teaching information literacy skills. The paper introduces a study on the strengths and challenges of GID as experienced by the educators and students of a school that integrated the framework into its pedagogical strategy and curriculum.

Method. Data was collected through interviews of seven teachers, a teacher librarian, nineteen students, the principal and two assistant principals. The interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Analysis. The interviews were analysed through thematic analysis in the Atlas.ti software.

Findings. The strengths of GID lied in structuring the inquiry process, evoking students’ interest, guiding students’ progress through the process and scaffolding the process through tools. Challenges were found in managing the open information environment, the experienced complexity and adapting tools to the teachers’ practices.

Conclusion. GID provides unique benefits as a pedagogical framework in information literacy instruction if integrated into the school’s curriculum and pedagogical practice. For individual teachers GID offers pedagogical design principles to guide and assess students especially in the first stages of the inquiry process.

Introduction

Formal school education is increasingly challenged by the need to address students’ information literacy skills. The rapidly changing information landscape asks for new pedagogical models to address handling and evaluation of information in various formats. Inquiry-based pedagogics seem particularly suited to address this challenge. Several inquiry-based models exist but many lack a research base or are only designed for specific project-based learning (e.g., Alifah, Ahmadi and Wardani, 2017; Syadzili, Soetjipto and Tukiran, 2018).

Guided Inquiry Design (GID) is a research-based framework designed to develop pedagogical practices that scaffold students’ independent inquiry (Kuhlthau, Maniotes and Caspari, 2015). It is based on the Information Search Process which describes thoughts, feelings and actions as students construct knowledge by exploring information sources (Kuhlthau, 2004). Convincing arguments show that the model remains valid also in the digital age (Todd, Kuhlthau and Heinström, 2005; Todd, Gordon and Lu, 2010; Lawal, Stilwell, Kuhn and Underwood, 2014; Kim, 2015). The pedagogical value of GID has been investigated (Chu, Tse and Chow, 2011; Chu, Chow, Tse and Kuhlthau, 2008). A deeper, generalizable, understanding of the benefits and pitfalls of the framework, however, requires research in varying school contexts, countries, school cultures, and pedagogical practices. To fully grasp GID’s potential in information literacy education it is not enough to study how it works in the classroom, without scrutinizing how it is integrated in the school’s strategy and curriculum.

This paper presents results of a case study of a school with several years’ experience in implementing Guided Inquiry Design. The case study was undertaken as part of the ARONI research project (https://blogs.sis.uta.fi/aroni/). ARONI aims to introduce research-based effective pedagogical practices in information literacy education for secondary education in Finland. GID was identified as a research-based model that potentially could inform this purpose. Effective pedagogical practices, however, need to serve the curriculum and be adapted to the school system within the country where they are applied. GID was developed in the US and has mainly been studied in USA, Asia and Australia. In order to learn from GID best practices we, therefore, regarded it as essential to elicit transferable pedagogical design principles from the model, rather than studying (and implementing) the model as a whole. Pedagogical design principles describes educational principles found in empirical research that are transferable across contexts and may be adapted according to needs in teaching practices (Cremers, Wals, Wesselink and Mulder, 2017).

The aim of the study was, therefore, to elicit pedagogical design principles that support student learning. For this purpose we investigated experiences of GID among teachers, the teacher librarian, students, the principal and assistant principals. The research questions are the following:

RQ 1. What are the experienced strengths of the GID framework for student learning, and why?

RQ 2. What are the experienced challenges in the GID framework, and why?

Literature review

Youngsters are fluent in googling for answers to everyday information needs, such as checking a fact or getting background information on Wikipedia. They, however, rarely master more advanced exploratory searches where information from various sources are combined (e.g., Walraven, Brand-Gruwel and Boshuizen, 2008). They struggle with planning and reformulating queries (Kiili, Laurinen and Marttunen, 2009), assessing credibility of information (Kiili, Laurinen and Marttunen, 2008) and identifying bias (Kiili, Leu, Marttunen, et al., 2017) and synthesizing information across sources (Sormunen and Lehtiö, 2011). Students entering college have been found to lack sufficient information literacy skills to do college-level research (Gross and Latham, 2012; Lanning & Mallek, 2017). Students themselves tend to overrate their information literacy (Gross & Latham, 2012; Ngo and Walton, 2016).

Teachers as information literacy educators

Teachers often implement inquiry tasks where students search and compile information for essays or presentations. Their attention, however, tend to centre on introducing the assignment and assessing the outcome, but neglecting the stages between. Consequently, students do not get explicit support in critical aspects of inquiry such as developing research questions or analysing information needs. This leaves students struggling with assessing information and constructing meaning from sources (Limberg, Alexandersson, Lanz-Andersson and Folkesson, 2008; Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014). Most students consequently tend to approach inquiry through a fact-finding approach (Limberg, 1998) which results in additive accumulative learning. Only a few approach their work in the analytical manner that more integrated knowledge construction requires (Todd, 2006). The key challenge is to structure the process of inquiry into stages, and how to guide students’ work and assess their progress at each stage (Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014; Limberg et al., 2008). The assessment of the end product (essay, presentation) offers only a limited possibility to assess students’ information literacy. Similarly, the scoring of the end product and post-process feedback is not enough for students’ self-reflection and learning. The teacher needs to make interventions and give feedback at the relevant moment during the assignment process.

Teachers are well aware of information literacy being a crucial part of education, but how to concretely address this in teaching practices is not evident. One explanation may be that this seldom is addressed in their own education (Tanni, 2013; Simard and Karsenti, 2016). Teachers, moreover, often perceive the open-ended information environment as threatening and difficult to manage (Kuhlthau et al., 2015). They tend to focus on teaching subject content also in student-centred inquiry (Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014). Lack of time and little access to needed technology are common barriers for teaching information literacy (Simard and Karsenti, 2016).

Nonetheless, there are also individual teachers who do develop advanced approaches to information literacy instruction (Alamettälä and Sormunen, 2018; Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014). Unfortunately these efforts may be in vain since complex knowledge work competences, such as information literacy evolve through extensive, versatile, and long-term across subjects practicing rather than one time interventions (Lakkala and Ilomäki, 2011). Information literacy is optimally taught as an integrated part of several courses over a long period with appropriate guidance and scaffolding (Chu et al., 2011). When information literacy education is embedded in actual curriculum teaching, digital literacies move beyond being learning tasks in themselves. Instead, they become tools for knowledge construction that can be applied for solving real-life problems (Coiro, Kiili and Kastek, 2017).

Some schools implement systematic approaches such as Guided Inquiry Design (Chu et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2008). However, not much research has been conducted on how the implementations have worked in various school contexts and cultures. Deeper insight into the benefits and problems would help to develop the pedagogical framework further.

GID as a pedagogical framework

The Guided Inquiry Design framework (Kuhlthau et al., 2015) provides a solid, research-based model for inquiry learning. It is grounded in the Information Search Process (Kuhlthau, 2004). The foundation for the ISP lies in constructivist learning where previous topical understanding forms the foundation to which the student links new discoveries (Kuhlthau, 2004). The knowledge construction process in the ISP describes how questions are identified, asked and answered (Cole, Beheshti & Abuhimed, 2017).

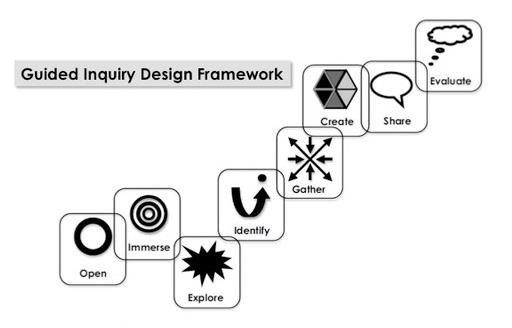

Studies of the ISP showed that students need time to familiarize themselves with a topic and freely explore it before they can form a focus. The focus, in turn, brings them forward in their research. This development is scaffolded in GID (Kuhlthau, Maniotes and Caspari, 2012). GID consist of eight phases: open, immerse, explore, identify, gather, create, share and evaluate (Figure 1). The unique contribution of GID is the amount of time dedicated to spur student interest and build their background knowledge before formulating a researchable question. It also emphasizes students’ third space, where the students’ own world connect to the curriculum content (Maniotes, 2005). The goal of GID is that students learn to manage the uncertainty inherent in constructing knowledge from information sources. GID enables five kinds of learning: information literacy, learning how to learn, curriculum content, literacy competence and social skills (Kuhlthau et al., 2012). GID instruction is based on team teaching, often the curriculum teacher, the teacher librarian, and a teacher with specialization in a related subject area. Inquiry tools scaffold the students’ process. Inquiry communities and inquiry circles help students collaborate and converse. Inquiry journals helps students reflect on information and their own learning process. Inquiry logs are used for managing information sources, while charts help to visualize topical understanding (Kuhlthau et al., 2012).

GID has been found effective in classroom studies (Chu et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2008). Teachers have noticed that if they allow time for the first stages of GID, it pays of in students’ interest (Alamettälä and Sormunen, 2018). Students’ own choices motivate them to become more engaged in analysing and interpreting information sources (Heath, 2015). Stronger engagement improves their learning (Chu, 2009). GID tools have also been found to be effective. Students who use inquiry logs become better at synthesizing information from various sources (Alamettälä & Sormunen, 2018). The combination of inquiry problem-based learning and collaborative teaching seem to be a particularly effective way to teach information literacy (Chu et al., 2011). Teachers may, however, experience GID as a too complex framework (Alamettälä and Sormunen, 2018).

Research has shown that students studying through Guided Inquiry based teaching receive significantly higher grades than control groups (Chu, 2009). This applies to both high and low-achievers (Chu, 2009). Some studies, however, suggest that only high-achievers, not low or middle mark achievers, reach the stage of focus formulation (Cole, Beheshti & Abuhimed, 2017).

Most inquiry based pedagogical methods focus on the students learning curriculum-relevant content. Although students are working independently with information sources, information literacy per se is seldom problematized and explicitly addressed in the models. We, therefore, identified GID as the most relevant model for our purpose, as a research-based model which clearly emphasizes and integrates IL as a learning goal. GID, moreover, contain pedagogical practices specifically designed to support IL development. It should be noted, however, that there are other inquiry models similar to GID. One example is the Personal Digital Inquiry model (Coiro et al., 2017). These models contain process-like structures, include stage-relevant activities, emphasize student interest and build on authentic tasks (Kiili, Mäkinen and Coiro, 2013).

Figure 1. The stages of the Guided Inquiry Design Framework (Kuhlthau et al., 2012). Published with the permission of authors

Material and method

The overarching research design of the study was a case study. Case studies rely on multiple sources of evidence, which are triangulated (Yin, 2014, p. 17). Data was collected in a high school in the USA that implemented Guided Inquiry Design. The school had seven years’ experience with GID when the data was collected in 2017. The total data set included course materials, interviews, observation in the classroom, three student surveys and students’ inquiry journals and inquiry logs. This paper will, however, only report findings from interviews with the principal, two assistant principals, seven teachers, the teacher librarian and students. The school underlined student-centred methods and project-based learning in its pedagogical vision. Teachers were encouraged to participate in further education and apply research-based innovative teaching methods.

Information literacy was also a central part of the school’s strategy. Critical evaluation of information sources was, for instance, an integrated goal in all courses at the school. The school had, moreover, specifically invested in the recruitment of well-educated visionary information professionals, which illustrates the value the school placed on the school library and its staff. GID was introduced in the school by the teacher librarian as a method that aligned with the school’s pedagogical vision and strategy. GID was, however, seen as one of several pedagogical methods in the school. The principals stated that despite GID’s successfulness they did not foresee it becoming the sole pedagogical method at the school.

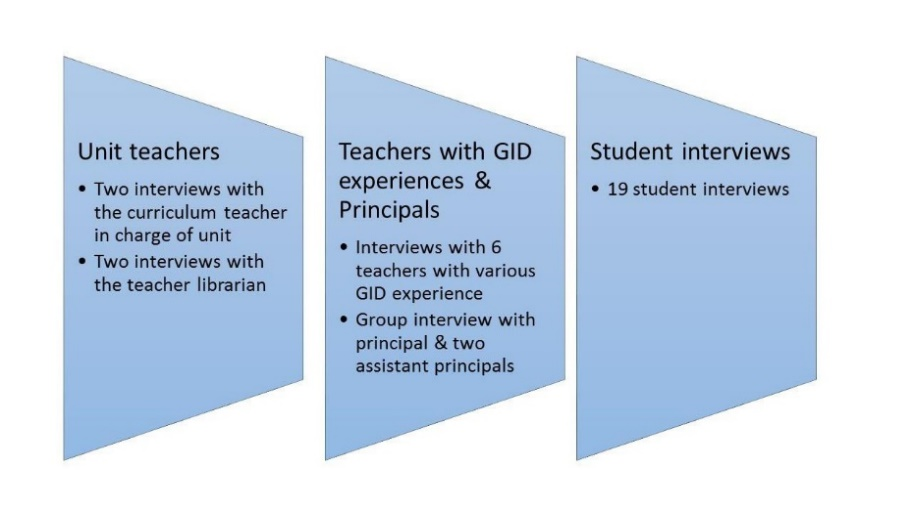

Data collection focused on two GID units in Literature where GID had been successfully implemented for seven years. The units had been revised yearly based on experiences the previous semester. The teacher librarian who had initiated GID in the school was interviewed two times about her experiences. Two one-hour interviews were conducted with the teacher in charge of the units in focus. The principal and two assistant principals were interviewed in an one-hour group interview. In addition six teachers with varying education and experience with GID were interviewed for one hour each.

The teachers’ insight into GID as a pedagogical framework varied substantially. Two of the teachers had attended a GID training institute and the others had been educated by GID courses offered in the school. The two teachers that had attended the institute had applied GID in their courses for seven years, and thus came with substantial insight into the method both theoretically and practically. Two teachers that had been trained in the school had applied it for four year and two with in-school training had tested one unit. One teacher had only attended in-school GID training and so far not implemented the method in practice. The subjects covered science, English and academic support. Nineteen students were interviewed about their learning experiences at the end of their unit. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conduscted interviews

The semi-structured interviews with teachers and the teacher librarian addressed the following themes: 1) general experience as teachers, 2) experience with GID, 3) influence of GID on student learning, 4) pedagogical value of GID, 5) challenges with GID, 6) lessons learnt and 7) plans for implementing GID in the future. In the interviews with the principal and the two assistant principals the same themes were addressed, but they were additionally asked about 1) overall pedagogical approach in the school, 2) introduction of GID and 3) GID in comparison with other pedagogical models. The students were asked to describe 1) their overall experience, 2) challenges and 3) learning in the specific GID project they had just undertaken. They were, moreover, asked to identify 4) benefits and 5) drawbacks and 6) what they would take with them from their learning experience (if anything).

Analysis of interviews

The interviews were transcribed and analysed in the Atlas.ti software. Data was examined through thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In the first round of coding excerpts of data where the respondents mentioned strengths or challenges of GID was selected for more detailed examination and given an initial code. The codes were then compared and grouped into larger categories. The categories were revised through several iterative coding phases, combining, deleting and creating new codes as needed by going back and forth between the entire dataset, the extracts and the analysis results. The codes were discussed between the researchers and modified as needed. As the main categories were quite clear and the sub-themes diverse with small frequencies each, specific counting of intercoder reliability was not considered relevant.

Results

The results are reported according to the two over-arching research questions regarding strengths and challenges of GID. It should be noted that fewer challenges than strengths are reported as respondents found it more difficult to acknowledge challenges. Teachers and students were randomly assigned codes as Teacher 1, Teacher 2, Student 1, Student 2 etc. The curriculum teacher will not be identified in the presentation of results for confidentiality reasons.

RQ 1. What are the experienced strengths of the GID framework for student learning, and why?

Overall, teachers and students alike felt that GID provided a new 21st century learning design. The Teacher Librarian described the difference to traditional inquiry:

(the teacher) ‘gave them questions, but they were mostly compilation-based questions … students were complaining the entire time, like they were very very needy. ….that neediness comes from the lack of student autonomy. …… yes they are getting some choice, but maybe it's not the right type of choice’.

Students mentioned that traditional research with a focus on the end product merely creates stress. They were used to being assigned a topic and deadline from their teachers and then being on their own, handling challenges independently along the way. In GID they particularly appreciated the constant presence and support from teachers. Teacher 1 described the difference to traditional inquiry this way:

I'm not the one that always has to know everything, …., but I can help them through. So that relationship is different than the traditional: here's the knowledge, here's your test. I just don't think that's what the world's really bout any more.

The main strengths are presented in the following subsection (in order of importance).

Making the invisible inquiry process visible

Five of the seven teachers stated that the emphasized and scaffolded process of inquiry was the most important part of GID. As Teacher 2 stated: ‘I think it teaches students how to think for themselves’. Teacher 4 underlined the importance of going through the experience, including the messiness: ‘[it is] one of those things, like swimming, you have to.. swim to actually learn it, you can’t just read books about it’. Recognizing the openness and struggles highlights the genuine messiness of dealing with information. As Teacher 3 put it ‘we don't say …you have two days to pick a topic and then you have to do the research. That's just not how, it flows. We're talking about how something naturally flows in research’. Acknowledging feelings helped students move through stages of research. Teachers stated that students had not been taught before that it's normal in the research process to go through different feelings, including frustration and anxiety. When feelings were acknowledged as a normal part of genuine research, the students moved more easily through the research process The principals stated: ‘learning kind of take a real organic and almost real open path, which is … exciting to see’.

Students mentioned that a structured process was important: ‘if you get a certain path to follow it helps you a lot more’ (Student 9). The clear process and tools that supported it made the inherently unstructured and messy inquiry process structured: ‘it is structured in a project that isn’t very structured’. (Student 4).

In the unit in focus, the process was acknowledged by grading students throughout the process, for example, in the form of compulsory inquiry logs and journals, instead of merely grading the end product. Students said that this enabled their learning. If only the end product had been graded their whole focus would shift there, while grading the process not only underlined its importance, but allowed them to concentrate on each of the steps along the way. There was no final product or presentation, which further illustrated the value of the ongoing process. As Student 3 put it:

If I would’ve known that I had to write an essay afterwards I probably would have been focusing … on the essay… But knowing that I wouldn’t have to do (it)…. allowed me to really … put my all into this and gather information, relentlessly I guess you could say.

Evoking, sustaining and scaffolding student motivation and agency

The teachers all underlined that they clearly saw the impact of GID on student agency and motivation and as a consequence, students’ learning. The teacher librarian explained that students became experts in their topics, which motivated them to investigate it in a deeper way. The principal conquered ‘when they are interested …. they're making a lot of connections that they otherwise may not have been able to make…. that can really be powerful…’. The importance of third space was underlined as important to give students autonomy, independence and trust. The students learnt to rely on their own independent ability to conduct research instead of simply following what their teacher dictated. As Student 8 simply put it: ‘that’s how my brain works: if I like something I’ll generally remember it’.

Allowing time to develop students’ interest, particularly the phases Open and Immerse built the foundation for the students’ ownership of the topic. Teachers underlined that motivation is not something that simply appears automatically, but instead needs to be enabled. As Teacher 2 expressed it: ‘you can’t teach a child how to be interested but you can give them tools to try to open that up in them’. Teacher 7 concurred: ‘those earlier stages with the Open ... really pull them in … gets their mind thinking in bigger pictures’. Students’ learning process did not end with the project. Instead, they felt that they were left with more questions and a curiosity to continue to investigate. Fifteen of the nineteen students stated that they had gained a deeper understanding of their topic than they would in normal classes. Through a personal connection the students realized the need for high-quality reliable information sources. The teachers had evidenced this: ‘…in their work cited, I see more credible sources’. (Teacher 3)

Students mentioned that they had been frustrated or confused at first, but their intrinsic motivation had made them push through challenging emotions. As Student 8 put it:

At first I was a bit frustrated … very confused. And when I get frustrated I tend to give up. But since this subject was something I’m interested in, it made me … push through my frustration. I pushed my way through it and did my work. And I usually don’t do that often.

Personal, professional and constant guidance through the process

The constant hands-on guidance of the students in developing their research questions and supporting them through the process was essential. As the Teacher Librarian explained:

… the teacher being involved with the research from, the start to the end, does allow the teacher to see where the students are struggling instead of who can do a good PowerPoint and who can't. Because that was what we were assessing previously.

The guidance was a balance between supporting student agency and providing support:

You don't want to hover over the student, they need to have their independent autonomy, but we also need…..frequent check-ins…. send us a paragraph response to how are you doing in the process, do you have questions, how can we help you, what are you thinking, what are you feeling. …And that's throughout the process. (Teacher 3).

By following each student’s progress closely, the teachers would know when to intervene:

Students can be a little bit timid in asking the teacher questions because that shows that they don't know or they don't understand. So shifting that as well, that it's okay to ask questions…., you're not bothering the teacher, we're not judging you on the questions you're asking us. We may judge you if you don't ask us any questions. (Teacher Librarian).

As Student 14 said: ‘(It was) helpful to have a teacher that was always like … you could ask her a question and she wouldn’t judge you’.

All teachers underlined the importance of collaborating with the teacher librarian with expertise in vetted sources, the inquiry process and developing researchable questions. As Teacher 1 stated: ‘this was someone who had an area of expertise, that I would never have’. Teacher 4 simply stated: ‘I could not have done it without her’. Administrators regarded the particular pedagogical value of GID as the scaffolded development of researchable questions, an insight that they had seen students take with them to other classes. They underlined the teacher librarian’s expertise in this regard: ‘The work that [the teacher librarian] does with students’ developing their question, it's fabulous. It's fabulous. Then you do see them carrying that ability to focus a question, to other classes’. Teachers concurred that developing a genuine research question deepened students learning. Teacher 2 stated: ‘it becomes about thinking and not about research’. Teacher 3 stated:

You can do an inquiry-based project, but if you don't have that professional guidance ….through the process, both in the actual skill based on the content, but also the emotional phases that you go through, I don't .. think…….you're gonna get that same type of success.’

Tools to scaffold and visualize the process

Results pertaining to the most mentioned tools (a note-taking tool based on inquiry logs, inquiry circles and inquiry journals) are reported in the following. Using vetted reliable information sources is not a specific GID tool, but using vetted information sources was mentioned by teachers and students alike as supporting student learning. Reliable information sources are consequently reported here as ‘tools’. The teacher librarian regarded the GID tools as essential both to support students learning but also as a means for teachers to follow students’ progress and identifying needs for support and intervention.

Although twelve of the nineteen student mentioned the note-taking tool as challenging, eleven also underlined the benefits of the tool (five mentioning tools as both challenging and helpful). They had conquered the challenges and the tool turned out helpful in the end. Student 9 said: ‘My first notecard … was a little difficult getting everything right and figuring out the process. But once I got down it was just I was flying’. Student 5 agreed: ‘So a little tedious. But I think in the end honestly I got more out of it because of it’. They explained that the notecards helped their thinking process and thus their learning. Student 6 explained:

Let’s say I’d usually just read something and … put it into my final product. But with this process I had to read it, analyse it, bring my own thoughts and then from there go on to my final process. So I think my work quality improved from that.

Teachers could also see the value of inquiry journals. As Teacher 3 said: ‘I think the reflection piece throughout the process. That I think is invaluable’.

The teacher librarian underlined the importance of students sharing their process experience and their learning throughout the process in inquiry circles or spontaneously in the class. ‘Students sharing …all the way through the process ... was where they gained the most, not …just listening to the student projects at the end, but ... all along’. The students all had their own independent topic for their projects, which they had chosen themselves out of genuine interest. They independently looked for information and produced the final report. Throughout the project, however, they interacted with other students in inquiry circles where they discussed about the inquiry process and shared what they had learnt about their projects. Teacher 5 had witnessed: ‘two kids that maybe hadn’t said two words to each other, really engaged… when you’re passionate about your subject … you love talking about it’. They also discussed as a group in the classroom. Teacher 4 could see that: ‘Involvement in their topics made the students open up’.

Ten of the nineteen students mentioned that using vetted reliable databases and information sources had helped them in their learning process. Exploring personally relevant questions, furthermore, underlined the importance of reliable sources. Student 19 had got insights from exploring his topic that he would implement into his own life. As he stated, his parents had given him similar advice through the years but he had ignored it. When he had found the same information from knowingly reliable sources, however, he believed in it and began to change habits accordingly. Students also mentioned that learning to use databases was important for them as they would soon proceed to college.

Research question 2. What are the experienced challenges in the GID framework, and why?

Lack of control

All the interviewed teachers regarded the lack of control as their main challenge in GID. Teachers commonly want to ensure that students learn essential curriculum content and saw a risk in allowing for more flexible investigation. It should be noted that despite close guidance of students throughout their projects, the teachers did not guide or suggest the particular topic for the students’ inquiry, nor the research questions. This meant that students could choose topics that were unknown also for the teachers. This created a genuine inquiry situation, but also a lack of control over the content for the teachers’ part.

The Teacher Librarian explained that

… the big challenge with guided inquiry is that they are giving up control. … Allowing students to … create a question that a teacher might not know the answer to … is really a big leap into ... risk-taking… that some teachers are just not ready for.

Teacher 5 explained ‘you want to share the answer with them. But instead, I would have to say: well that’s a good question. I’m uncomfortable having those kind of conversations’. Teachers’ identity is, moreover, often built around the content of their teaching. The Teacher Librarian explained: ‘[this is] very scary for teachers, … a lot of teachers at high school .. have an identity formed around their content…’. Teachers also mentioned, however, that although they constantly struggled with the openness and lack of control inherent in teaching through GID, the effort payed off.

The same lack of control was also challenging for the students, particularly for the highest performing ones. The teacher librarian explained: ‘Because they're very used to okay, you're gonna do one two three four five, make your PowerPoint, write your paper, whatever and turn it in. And what you turn it … is what we're grading’. The honours students wanted to know exactly on what they are graded and how to get their A. As student 16 said:

It was kind of different to look at a question that’s more like open-ended.. ..rather than …specific, which I think I kind of struggled with because I like getting answers. ….So it was a little difficult for me.

The Teacher Librarian, however, regarded the lack of control as a key part of learning: ‘A big part of guided inquiry is the sitting in the uncomfortable….as human beings the only way that we do grow, is to be uncomfortable’.

Prescribed structure

The administrators regarded the major challenge with GID as being prescribed: ‘Some teachers are not willing to engage in it because it's so prescribed and they're used to doing things their own way..’. Teachers mentioned that the whole GID model with elements from the inquiry process to five different learning goals could appear daunting.

This process.. one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, eight things. Yeah, I’m sure.. they’re all really important but eight was too many for me to take in……. The five kinds of learning was too much … so I didn’t do anything with that. Extended team of experts, not really. (Teacher 6).

Teacher 7 had first heard about GID from her students talking about a very detailed challenging GID unit. The students had complained about the stress of the project and described how over-whelming they felt it was. Teacher 7 had, however, realized that

… the experience I heard about … is just one way. There’s lot of different ways to tailor-make guided inquiry for the amount of time you have, the number of students, the level of the students, so that was very reassuring that there was flexibility within it.

The teachers also experienced GID as too time consuming. Choosing only the core elements from the process made it more workable and appealing. Teacher 5 said: ‘the idea of like, oh my God, doing all these steps……So you turn it off ….. I think .... try a couple of pieces. Like a buffet. And you can go back and have more later’.

Implementation of tools into the school’s practices

Twelve of the nineteen students mentioned the note-taking software as challenging. As Student 17 said, the note- taking tool was ‘bogging down the process’. It required them to learn a new software on top of the actual project, which took attention and effort away from actually working with information. As Student 6 explained:

I would have been able to get right into it much faster …. I … felt ... overwhelmed knowing that I had to use databases and all these articles from certain websites and on top of that take all my notes and things on a program and software that I was unfamiliar with.

It also forced students into a structure that did not necessarily fit their own way of working with information. As student 1 pointed out:

I myself am more of a creative (person) in terms of my writing and … in how I organize things. I don’t particularly like a heavily structured method of compiling information. Not every student learns the same way.

It should be underlined that the note-taking tool is not a formal part of the GID framework. The school had, however, implemented it to support GID processes of note-taking and reflection.

Discussion, limitations and conclusions

The unique element of GID is allowing time to create interest, ownership and develop a genuine open research question before exploring a topic. Through the deep investment in the process, students realize the importance of choosing reliable information sources. They are intrinsically motivated to analyse and synthetize sources as they are invested in getting to the bottom of their research topic. Information literacy skills are thus developed as a side note in the process of investigating a curriculum related topic.

GID highlights the whole messy process of creating knowledge through independent exploration by clearly staging the process stepwise and scaffolding the students through. It reveals the information search process as just as complex and challenging as it organically often is. Acknowledging frustration and anxiety as normal helped students accept them and move through them (supporting Kracker and Wang, 2002; Savolainen; 2015). The often invisible or not problematized process of dealing with information becomes manageable when it is made visible and structured. Grading of each step of the process further underlined the importance of the process rather than the product. According to Sundin (2008) information literacy from a process perspective is to understand how to work with information, including different elements of the process.

GID emphasizes the first four stages before the students begin to gather information (Kuhlthau et al., 2012). Studies on current information literacy teaching in schools show that it is exactly these four stages that are typically overlooked (Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014). This leave the students overwhelmed and unprepared to master the challenges of web searching. Structuring the inquiry assignment into stages, and scaffolding the first four stages more explicitly, is maybe the most important change needed in modern pedagogical practices. A group of teachers evidenced this in students’ engagement and performance when they adopted staging and scaffolds for the first GID stages (see Alamettälä and Sormunen, 2018).

Students valued the close guidance by teachers throughout their process. Guidance is nothing unique for GID, but the model does contain unique features in that co-teaching is emphasized and guidance focus both on curriculum-content and information literacy practices. The professionalism of the teacher librarian in guiding information literacy practices was highly valued by teachers.

GID was experienced as somewhat prescribed, confirming findings by Alamettälä and Sormunen (2014). GID is specifically designed to be adaptable and flexible (Kuhlthau et al., 2012), but the way the model is presented with five different learning goals and various tools, may seem overwhelming. The teachers’ challenges with implementing GID, however, largely correlated with the education and experience they had with the method, suggesting that what initially may appear daunting becomes manageable with time. With experience, the teachers also learnt to incorporate and benefit from more elements of the model.

The note-taking software is not a part of the GID framework, but was designed to support GID processes of reflection and managing sources. The software was predominantly experienced as a technical tool for most students. Students focused on the mechanical recording of information sources, rather than using it as a tool for synthetizing information from various sources, as intended by the teachers. GID underlines the importance of incorporating students own learning styles in the process, so limiting or streamlining note taking processes can be a barrier in the knowledge construction process. Some students, however, did recognize the analytical value of the tool. This is in line with the results of Alamettälä and Sormunen (2018) who observed that many students did not adopt the use of inquiry log neither in printed nor in digital form, although some students reported benefits of using the tool in managing sources. As observed in an earlier study (Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014), teachers apply their personal professional expertise and intuition to design various types of units and assignments to teach inquiry and information literacy skills. Thus, we need more reported case studies on how GID and related frameworks can be varied in their implementations to describe the flexibility of the framework in a more tangible way.

It should be noted that the data was collected in a high performing school where students were focused on achievement. The results are also based on a limited number of interviews. Students were interviewed towards the end of the GID unit. Although they did report struggles they were largely positive, perhaps partly as they already successfully had completely the project, and were not in the middle of the challenges midpoint. The unit in focus, moreover, had a long experience applying the method and had also adjusted it over the years. The overall trends, however, were quite clear in the data with result repeated across interviews in the voices of principals, teachers, teacher librarian and students. This suggests that the overall trends, nevertheless, contain grains of truth that could be useful for further understanding of the challenges and successful elements of GID.

The results underlined the importance of school culture and vision when introducing methods such as GID. The studied school valued student-centred pedagogical practices, student research and emphasized the importance of students learning information literacy skills, such as evaluation of information, as an integrated part of all courses. The school, moreover, valued new pedagogical practices and encouraged teacher further education. This formed a fruitful context for GID as a practice that fitted into the school’s vision, mission, curriculum and practices. Our results thereby underline the importance of aligning any new pedagogical model, such as GID, with the general pedagogical culture within the school. If GID aligns with the vision, it also motivates teachers to use the method. We deem student-centred methods, a school’s vision that values and underline information literacy, teacher resources (e.g. for further education) as important preconditions for successful implementation of GID.

Student interest and agency is arguably nothing unique as this has been a staple feature in constructivist learning ever since Dewey (1938/1997). What is unique, however, is the way GID gives teachers tools to enable and sustain this interest, adapted to the independent inquiry of the information age. We, therefore, regard particularly the first stages of the GID process and the tools provided to enable these stages as one of the most essential contribution of GID to student learning. GID offers unique benefits as a pedagogical framework in information literacy instruction if integrated into the school’s strategy, curriculum and pedagogical practice. In the perspectives of individual teachers GID offers ideas to develop pedagogical design principles to guide and assess students especially in the first four stages of the inquiry process. This opens perspectives to solve the blackbox problems (invisibility of the inquiry process to the teacher) observed (cf. Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014; Limberg et. al., 2008) common in the present pedagogical practice of information literacy instruction.

Acknowledgements

The study was part of the ARONI project funded by the Academy of Finland (grant’s no. 285638). The authors thank the participating school, and especially the principals, teacher librarian, teachers, and students for giving their time for interviews. We are grateful to Carol Kuhlthau, Leslie Maniotes, and Ross Todd who facilitated the data collection in the U.S.A. We also thank Xiaofeng Li for her help in the data collection and Liisa Ilomäki for her advice on the study.

About the author

Jannica Heinström is a Senior Lecturer at Åbo Akademi University, Department of Information Studies, Fänriksgatan 3 B, 20500 Åbo, Finland. She received her PhD from the same university and her research interests are in information behaviour, individual differences and learning. She can be contacted at jannica.heinstrom@abo.fi.

Eero Sormunen is a Professor in University of Tampere, Faculty of Communication Sciences, 33014 University of Tampere. He received his PhD from the same university and his research interests are in information literacy, online research and learning. He can be contacted at eero.sormunen@uta.fi.

References

- Alamettälä T., Sormunen E. (2018). Lower secondary school teachers’ experiences of developing inquiry- based approaches in information literacy instruction. In: Kurbanoğlu S., Boustany J., Špiranec S., Grassian E., Mizrachi D. & Roy L. (Eds.), Information literacy in the workplace. ECIL 2017 (pp. 683 -692). Cham, Switzerland: Springer (Communications in Computer and Information Science, 810).

- Alifah, R.N., Ahmadi, F. & Wardani, S. (2017). Using SETS approach on cognitive learning achievement and naturalist intelligence of elementary school fourth grade students. Journal of Primary Education, 6(3), 232–240.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Chu, S.K.W. (2009). Inquiry project-based learning with a partnership of three types of teachers and the school librarian. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 60(8), 1671-1686.

- Chu, S.K.W., Chow, K., Tse, S. & Kuhlthau, C.C. (2008). Grade 4 students’ development of research skills through inquiry-based learning projects. School Libraries Worldwide, 14(1), 10–37.

- Chu, S.K.W., Tse, S. & Chow, K. (2011). Using collaborative teaching and inquiry project-based learning to help primary school students develop information literacy and information skills. Library and Information Science Research, 33(2), 132–143.

- Cole, C., Beheshti, J. & Abuhimed, D. (2017). A relevance model for middle school students seeking information for an inquiry-based class history project. Information Processing & Management, 53(2), 530-546.

- Coiro, J., Killi, C. & Castek, J. (2017). Designing pedagogies for literacy and learning through personal digital inquiry: theory and practice from New London to New Times. In F. Serafini & E. Gee (Eds.), Remixing multiliteracies: 20th anniversary (pp. 137-150). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Cremers, P.H., Wals, A.E., Wesselink, R. & Mulder, M. (2017). Utilization of design principles for hybrid learning configurations by interprofessional design teams. Instructional Science, 45(2), 289-309.

- Dewey, J. (1997/1938). Experience and education (Original work published 1938). In J.A. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey: the latter works, 1938-1939 (Vol. 13). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Gross, M. & Latham, D. (2012). What's skill got to do with it? Information literacy skills and self‐views of ability among first‐year college students. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 63(3), 574-583.

- Heath, R.A. (2015). Toward learner-centred high school curriculum-based research: a case study. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 47(4), 368 - 379

- Kiili, C., Laurinen, L. & Marttunen, M. (2008). Students evaluating Internet sources: from versatile evaluators to uncritical readers. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 39(1), 75–95.

- Kiili, C., Laurinen, L. & Marttunen, M. (2009). Skillful Internet reader is metacognitively competent. In L.T. Hin & R. Subramaniam (Eds.), Hanbook of research on new media literacy at the K-12 Level: issues and challenges (Vol. II, pp. 654–668). Retrieved from http://www.igi-global.com/chapter/handbook-research-new-media-literacy/35943

- Kiili, C., Leu, D.J., Marttunen, M., Hautala, J. & Leppänen, P.H. (2017). Exploring early adolescents’ evaluation of academic and commercial online resources related to health. Reading and Writing, 31(3), 533-557.

- Kiili, C., Mäkinen, M. & Coiro, J. (2013). Rethinking academic literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57(3), 223-232.

- Kim, S.U. (2015). Exploring the knowledge development process of English language learners at a high school: how do English language proficiency and the nature of research task influence student learning?. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(1), 128-143.

- Kracker, J. & Wang, P. (2002). Research anxiety and students' perceptions of research: an experiment. Part II. Content analysis of their writings on two experiences. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(4), 295-307.

- Kuhlthau, C.C. (2004). Seeking meaning : a process approach to library and information services. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Kuhlthau, C.C., Heinström, J. & Todd, R. J. (2008). The 'information search process' revisited: is the model still useful? Information Research, 13(4), paper 35 Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/13-4/paper355.html

- Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L.K. & Caspari., A.K. (2012). Guided Inquiry Design: a framework for inquiry in your school. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

- Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L.K. & Caspari, A.K. (2015). Guided inquiry - learning in the 21th century (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

- Lakkala, M. & Ilomäki, L. (2011). Unfolding experienced teachers’ pedagogical practices in technology- enhanced collaborative learning. In Connecting computer-supported collaborative learning to policy and practice: CSCL2011 conference proceedings (Vol. I, pp. 502–509). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10138/28475

- Lanning, S. & Mallek, J. (2017). Factors influencing information literacy competency of college students. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(5), 443-450.

- Lawal, V., Stilwell, C., Kuhn, R. & Underwood, P.G. (2014). Information literacy-related practices in the legal workplace: the applicability of Kuhlthau’s model to the legal profession. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 46(4), 326-346.

- Limberg, L. (1998). Att söka information. En studie av samspel mellan informationssökning och lärande. Göteborgs universitet/University of Gothenburg: Department of Library and Information Studies. Institutionen för biblioteks- och informationsvetenskap

- Limberg, L., Alexandersson, M., Lantz-Andersson, A. & Folkesson, L. (2008). What matters? Shaping meaningful learning through teaching information literacy. Libri, 58(2), 82–91. doi:10.1515/libr.2008.010

- Maniotes, L. (2005). The transformative power of literary third space. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, School of Education, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO.

- Ngo, H. & Walton, G. (2016). Examining the practice of information literacy teaching and learning in Vietnamese upper secondary schools. Education for Information, 32(3), 291-303.

- Savolainen, R. (2015). Approaching the affective factors of information seeking: the viewpoint of the information search process model. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014: Part 2. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/20-1/isic2/isic28.html

- Simard, S. & Karsenti, T. (2016). A quantitative and qualitative inquiry into future teachers’ use of information and communications technology to develop students’ information literacy skills. Canadian Journal of Learning and Technology/La revue canadienne de l’apprentissage et de la technologie, 42(5), 1-23.

- Sormunen, E. & Alamettälä, T. (2014). Guiding students in collaborative writing of Wikipedia articles – how to get beyond the black box practice in information literacy instruction. In J. Viteli & M. Leikomaa (Eds.), Proceedings of EdMedia 2014 – World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications. Vol. 2014, No. 1. Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/147767/

- Sormunen, E. & Lehtiö, L. (2011). Authoring Wikipedia articles as an information literacy assignment – copy- pasting or expressing new understanding in one’s own words? Information Research, 16(4). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/16-4/paper503.html

- Sundin, O. (2008). Negotiations on information-seeking expertise. Journal of Documentation, 64(19), 24-44.

- Syadzili, A.F., Soetjipto & Tukiran (2018). Guided inquiry with cognitive conflict strategy: drilling Indonesian high school students’ creative thinking skills. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 947(1). doi:10.1088/1742-6596/947/1/012046

- Tanni, M. (2013). Teacher trainees’ information seeking behaviour and their conceptions of information literacy instruction. Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press. Retrieved from http://tampub.uta.fi/handle/10024/68249

- Todd, R.J. (2006). From information to knowledge: charting and measuring changes in students' knowledge of a curriculum topic. Information Research, 11(4), paper 264. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/11-4/paper264.html

- Todd, R.J., Gordon, C. & Lu, Y. (2010). Report of findings and recommendations of the New Jersey school library survey phase 1: one common goal: student learning. New Brunswick, NJ: Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries at Rutgers University.

- Walraven, A., Brand-Gruwel, S. & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2008). Information problem solving: a review of problems students encounter and instructional solutions. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(3), 623–648.

- Yin, R.K.(2014). Case study research: design and methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.