Why textual search interfaces fail: a study of cognitive skills needed to construct successful queries

Gerd Berget, and Frode Eika Sandnes.

Introduction. It has been suggested that cognitive characteristics may affect search. This study investigated how decoding abilities, short-term memory capacity and rapid automatised naming skills relate to query formulation.

Method. A total of twenty dyslexic participants and twenty non-dyslexic controls completed four standardised cognitive tests and solved ten search tasks in a Norwegian library catalogue.

Analysis. The relationships between search patterns and cognitive profiles were explored using correlation analysis.

Results. Results show that decoding skills relate to query lengths and spelling errors, short-term memory relates to the number of iteration cycles, and rapid automatised naming relates to query times.

Conclusion. Search interfaces should be robust to errors in short queries to accommodate users with reduced cognitive function.

Introduction

Textual search is a common method for interaction between people and computers. Since the introduction of the Web, search has become increasingly important, partly due to the large amount of online information. In the initial World Wide Web project proposal, Berners-Lee and Cailliau (1992) emphasised two elements, namely hypertext and searchable indexes. This model allows users to provide search criteria such as keywords and retrieve a result list of hyperlinks to relevant documents. Textual search is also used in other domains such as when specifying the destination while purchasing a train ticket using a self-service kiosk or smartphone apps (Sandnes, Tan, Johansen, Sulic, Vesterhus and Iversen, 2012).

There are high expectations for the digital literacy of users. Digital literacy exceeds the ability to use digital devices or software, and includes tasks such as constructing knowledge from Web navigation and evaluating the quality of information (Eshet-Alkalai, 2004). Moreover, the large amounts of online information may cause information overload (Bawden and Robinson, 2009), thus requiring well-developed search skills to locate and assess information.

Search user interfaces have changed little over the years (Chen and Chua, 2013). Still, some innovative systems have emerged that provide search through speech (Trippas, Spina, Cavedon and Sanderson, 2017), images (Wang, Zhang, Li and Ma, 2008) or contextual information such as Global Positioning System coordinates on smartphones. For example, one app retrieves information about star constellations when users point the smartphone towards a particular direction in the sky (Ouilhet, 2010). Nevertheless, the traditional text-based search user interfaces are still dominating (Chen and Chua, 2013).

Textual search may be regarded as a straightforward activity. Users input keywords and retrieve documents using a results page. However, searching for information involves a complex set of cognitive skills, such as scanning, reading and processing information (Brand-Gruwel, Wopereis and Vermetten, 2005). Information retrieval has for a long time been regarded as cognitive in nature (Ingwersen, 1996), and it has been suggested that query formulation demands a significantly higher cognitive load than result list assessment (Gwizdka, 2010). Nevertheless, limited research attention has been directed towards the cognitive skills needed to conduct successful information searching or query construction.

Research into the search behaviour of users with dyslexia may be relevant in this context because of the cognitive profile related to this diagnosis. Although dyslexia is most commonly associated with reading and writing difficulties (Ferrer, Shaywitz, Holahan, Marchione and Shaywitz, 2010), dyslexia also affects other cognitive skills. According to Beidas, Khateb and Breznitz (2013), the cognitive profile of users with dyslexia is under debate. However, certain cognitive skills are frequently reported to be impaired, such as short-term memory capacity (Perez, Poncelet, Salmon and Majerus, 2015) and rapid automatised naming (Norton and Wolf, 2012), the ability to quickly recall the names of, for example numbers, colours or objects (Lervåg and Hulme, 2009). Many users with dyslexia share a common cognitive profile, but the degree of dyslexia and impairment in cognitive abilities vary (Snowling, Gallagher and Frith, 2003). Consequently, there are notable differences in this user group, making it purposeful to regard dyslexia as a continuum rather than a fixed condition with one specific cognitive profile.

Previous research indicates that users with reading difficulties such as dyslexia find query formulation challenging, especially in search systems with no help functions and a high demand for correct spelling (Berget and Sandnes, 2015). It is also suggested that Web navigation and result lists might be troublesome due to impaired short-term memory capacity (Al-Wabil, Zaphiris and Wilson, 2007; MacFarlane, Albrair, Marshall and Buchanan, 2012). Although previous research has suggested that users with cognitive impairments experience challenges with information searching, less focus has been directed towards which cognitive characteristics influence information searching the most. One exception is a study suggesting that short-term memory may be an important skill for result list assessment (MacFarlane, et al. 2012).

Against the backdrop of the ubiquity of the search interface and the variety of cognitive abilities among the population, more knowledge is needed on how the cognitive profile of users affects the construction of queries so that more effective search interfaces can be developed. Query formulation constitutes the basis for the search process. If query formulation fails, the rest of the search process will become harder, for instance the misguided navigation of irrelevant result lists.

This study investigates how decoding skills, short-term memory capacity and rapid automatised naming affect searching. All these characteristics are usually impaired to various degrees in users with dyslexia, which makes this a purposeful user group to investigate in such a context. The following research question forms the basis for this study:

RQ: To what degree are the cognitive skills typically affected by dyslexia (decoding, short-term memory and automated naming) needed to conduct successful queries?

The overall purpose of this work was to obtain a more precise understanding of how users interact with search systems during query formulation. The main contribution of this study is new empirical data connecting cognitive skills to information search performance among dyslexics and non-dyslexics, in particular how short-term memory is related to query formulation. The findings complement previous studies on how short-term memory is tied to results assessment among users with dyslexia (MacFarlane, et al., 2012). These results have implications for search user interface design and the findings apply to a larger user group than merely people with dyslexia, because these cognitive skills may be affected by other factors besides impairments. For instance, spelling mistakes may be caused by hastiness, lack of focus, divided attention, hitting incorrect keys on small keyboards or unfamiliar words. Short-term memory may be affected by age (Li, et al. 2008), lack of sleep (Gohar, et al. 2009), exposure to stress or posttraumatic stress disorder (Bremner, et al. 1995), to mention a few.

Background

Search functionality has become common in many types of computer systems, yet it is claimed that the search interface has changed little over the years (Chen and Chua, 2013). There has been an increased interest in studying the information searching behaviour of users in general (Wilson, 1999) and also people with cognitive and sensory impairments (Hill, 2013). User knowledge is needed to develop more usable search interfaces. According to a review of information science literature from 2000 to 2010, most of the studies related to impairments addressed Web, databases and software (Hill, 2013). However, the main emphasis was on visual impairments, few studies discussed cognitive impairments.

There have been several innovative and diverse attempts at tailoring user interfaces and making assistive software for users with dyslexia, for instance the development of guidelines targeting users with dyslexia (Miniukovich, Angeli, Sulpizio and Venuti, 2017; Venturini and Gena, 2017), configuration and personalisation (Gregor and Newell, 2000), how to present text (Appert and Truillet, 2015, 2016), improving the spelling among dyslexic children through games (Rello, Bayarri, Otal and Pielot, 2014), reading tutors (Schneider, Dorr, Pomarjanschi and Barth, 2011), learning through tangible computing (Fan and Antle, 2015; Fan, Antle and Cramer, 2016), detecting errors caused by dyslexia on the Web (Baeza-Yates and Rello, 2011) and incorporating individuals with dyslexia into the team of developers (González, 2017), to mention a few.

The first cognitive skill included in this study is decoding, which refers to the ability to decipher words based on the alphabetical principle (Høien-Tengesdal and Tønnessen, 2011), and is assumed to be closely related to reading and spelling (Sparks, Patton, Ganschow, Humbach and Javorsky, 2008). A few studies have investigated spelling errors in queries, a common phenomenon in search systems (Duan and Hsu, 2011), with reported error rates from 6% to 25% of the queries (Berget and Sandnes, 2015, 2016; Cucerzan and Brill, 2004; Drabenstott and Weller, 1996). One study on users with dyslexia reported that erroneous queries had a significant effect on search performance in a search system with high demands for correct spelling (Berget and Sandnes, 2015), while this effect was not found in a system with more tolerance towards spelling errors (Berget and Sandnes, 2016). Moreover, users with dyslexia did not utilise the autocomplete function, due to an intense focus on the keyboard during query input (Berget and Sandnes, 2016).

The significant differences in queries with spelling errors reported in previous research forms the basis for the first hypothesis (H1). The assumption is that users with reduced decoding skills will formulate shorter queries to decrease the risk of spelling errors, while at the same time reduced decoding skills will cause a higher portion of queries with errors.

H1: Decoding skills affect query lengths and the portion of misspelled queries.

The second cognitive characteristic investigated in this study is short-term memory, the ability to temporarily store and manipulate information needed for various complex cognitive tasks, for instance reasoning, learning and language (Baddeley, 2003). Short-term memory can be divided into visuospatial and verbal memory. Visuospatial memory stores information about the surrounding environment, such as spatial placement, colours and shapes (Mammarella, Pazzaglia and Cornoldi, 2008). Verbal short-term memory is connected to verbal-linguistic information and is among other things, related to text comprehension (Kane, et al. 2004).

According to Shneiderman, Byrd and Croft (1997), one important guideline for search user interfaces is to reduce short-term memory load. Memory load during query formulation can be reduced by leaving the query in the browser when the user pushes the back button and by including query previews (also referred to as autocomplete), where recognition is more important than recall (Hearst, Elliott, English, Sinha, Swearingen and Yee, 2002).

Short-term memory has also been discussed in the context of dyslexia, where it has been suggested that reduced short-term memory leads to longer search times and the assessment of fewer documents (MacFarlane, Al-Wabil, Marshall, Albrair, Jones and Zaphiris, 2010; MacFarlane, et al., 2012). Users with dyslexia have also been reported to be more inclined to look up and down in the search user interface compared to non-dyslexics, and it is suggested that reduced short-term memory capacity causes this backtracking behaviour (MacFarlane, Buchanan, Al-Wabil, Andrienko and Andrienko, 2017). This finding is supported by another study, which suggested a connection between search challenges faced by dyslexic users and short-term memory capacity (MacFarlane, et al. 2010).

The second hypothesis (H2) is based on the reported work on dyslexia and the suggested connections between short-term memory and search behaviour. In the context of query formulation, the assumption is that reduced short-term memory will cause a higher number of iterations, because the user may forget the content or spelling from previous queries during query refinement:

H2: Short-term memory capacity relates to the number of iteration cycles during information search.

The third, and final, cognitive ability addressed in this study is rapid automatised naming, namely the ability to verbally label visual stimuli (Neuhaus, Foorman, Francis and Carlson, 2001). There is little research on the relationship between rapid automatised naming and information searching, and consequently few studies to build on. However, the concepts of precision and recall, measurements that are usually applied in relation to search engine result pages, might be particularly relevant in this context.

Precision is a measure of how many of the retrieved results are relevant for the query submitted, while recall measures how many of the relevant documents in the database are actually retrieved (Oliveto, Gethers, Poshyvanyk and Lucia, 2010). Precision and recall are contrasting measures, and high precision and high recall cannot be achieved simultaneously There is a close relationship between the precision level of a query and the result list content. By submitting long and precise queries, users should receive a more precise result list.

According to Shneiderman, Byrd and Croft (1997) search boxes should include enough space to allow for long queries, to encourage users to formulate long search strings that provide more precise result lists. Consequently, for users who struggle with result list assessment, the query formulation may be particularly important and affect query formulation strategies. For instance, Sahib, Tombros and Stockman (2012) reported that users with visual impairments find navigation of result lists challenging, and therefore formulate more expressive queries with the intention of reducing the number of iterations with the search system.

Users with dyslexia are also reported to have challenges with result list assessment (Cole, MacFarlane and Buchanan, 2016; MacFarlane, et al. 2010; MacFarlane, et al. 2012; MacFarlane, Buchanan, et al., 2017) and may therefore apply similar strategies, formulating longer queries to ease the result list assessment. However, the price of longer queries is a higher number of words that must be spelled correctly, thus increasing the possibility of error. Moreover, users with impaired random automatised naming capacity may take more time recalling query terms and consequently find formulation of longer queries more demanding. The third hypothesis (H3) investigates rapid automatised naming:

H3: Rapid automatised naming influences query lengths and search times.

In this study, dyslexic and non-dyslexic users were not regarded as two separate groups. The participants were analysed according to a continuum of measurements resulting from the cognitive tests. By including dyslexic and non-dyslexic participants, the dataset included a broad spectrum of measures for decoding skills, short-term memory capacity and rapid automatised naming, and allowed for correlation analysis between query characteristics, (namely query lengths, spelling errors, iteration cycles and query times) and cognitive skills.

Method

Participants

The participants comprised forty students from universities in Norway, twenty were diagnosed with dyslexia and twenty were matched controls, all were Norwegian native speakers. The control group was assembled according to field of study, year of study, gender and age. The gender distribution was 60% females and 40% males. The students were aged 19 - 40 years, with a mean age in the dyslexia group of 24.2 years (SD = 5.2), and 23.6 years (SD = 3.8) in the control group. The students were enrolled in a bachelor’s or master’s programme, with a mean year of study of 2.4, for both the dyslexia group (SD = 1.2) and the control group (SD = 1.0) (bachelor’s students are valued 1-3, master students 4-5). Different fields of study were represented, such as engineering, nursing, pedagogics, police studies and social sciences. No students from library and information science were included, because of the extensive curriculum on information retrieval.

Procedure

Formal permissions to conduct the experiment were acquired according to the national standards of ethics. The experiment was conducted over two sessions. The first session started with general information about the study and signing of a consent form, followed by an interview regarding search experience. The participants completed a visual acuity test to ensure that reduced vision would not affect the results. All participants had normal or normal to corrected vision (with at least an acuity of 0.8 with both eyes open and 0.6 on each eye separately). Four cognitive tests were also conducted, one test for decoding skills, two short-term memory tests and one test for rapid automatised naming. In a second session, the participants completed a search experiment in the Norwegian academic library catalogue Bibsys Ask. (Note that Bibsys ask was decommissioned and replaced with a new search system Oria in 2015.)

Three more participants (two with dyslexia and one control) were originally recruited, but were excluded due to the results on the visual acuity test and dyslexia screening test. The excluded control user who received a low score on the screening test was given advice to follow up on this by contacting a specialist. The participant was given contact information for specialists at the university and for a contact person in the organisation Dyslexia Norway.

Stimulus

Cognitive tests

The Norwegian dyslexia screening test Ordkjedetesten (translates as The Word Chain Test) was applied to assess decoding skills (Høien and Tønnesen, 2008). This test is based on word recognition and consists of ninety word chains, where four regular words are put together with no blank spaces, and the task is to mark the breaks between the words. All marks in a word chain have to be correct to get one point. The maximum score is ninety points, and diagnostic tests for dyslexia are recommended for adults who score below forty-three points (Høien and Tønnesen, 2008).

A computer based Corsi Block-Tapping Test from the Psychological Experiment Building Language (PEBL) test battery (Mueller, 2010) was used to assess visuospatial memory, a test reported to be widely used for such purposes (Pagulayan, Busch, Medina, Bartok and Krikorian, 2006; Vandierendonck, Kemps, Fastame and Szmalec, 2004). In the PEBL version used herein, users are presented with a display of nine navy blue blocks irregularly laid out on a screen in fixed positions. The task is to remember block sequences. One block at a time is highlighted in yellow, and the task is to reproduce the sequence in the correct order. The first sequence consists of two blocks and increases by one block every other round. When the participant fails to recall both sequences of the same length, the test is completed. Scores are given according to the length of the last remembered sequence.

A computerised Digit Span Test from the PEBL test battery (Mueller, 2010) was used to measure verbal short-term memory capacity. The participant is first informed about the length of the following sequence. Then, digits are presented on the screen, one at a time, and the task is to remember the digits and then input the sequence. An extra digit is added every second round. The test is completed when the participant fails to recall both sequences of the same length. Scores are based on the length of the last recalled sequence.

A Victoria Stroop test, also known as a colour-word-interference test, was produced according to the instructions in Strauss, Sherman and Spreen (2006). This test consists of three cards. However, the first card, also referred to as Dot-card, may be used in isolation as an indicator of rapid automatised naming skills (Helland and Asbjørnsen, 2004). The Dot-card consists of twenty-four dots in four different colours (green, red, yellow and blue), and the participant is instructed to read the colours out loud. Output of this test is reading time and number of errors, where high scores indicate impaired naming skills (Helland and Asbjørnsen, 2004).

Task

The Norwegian academic library catalogue Bibsys Ask was used for the search experiment. This database has no query building aids and no tolerance for spelling errors. The basic search user interface in Norwegian was applied for all tasks, consisting of a search box and a submit button. The participants were asked to solve ten predefined tasks in Norwegian (see Table 1). Participants were allowed to use additional sources if needed but were instructed to perform at least the first and last queries in the library catalogue.

| Task | Task (originally given in Norwegian) | Expected query terms | Translated query terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Find a document about Vigeland Sculpture Park? | Vigelandsparken | Vigeland Sculpture Park |

| 2 | In which year was the book “Rock carvings in Hedmark and Oppland” published? | helleristninger Hedmark Oppland |

rock carvings Hedmark Oppland |

| 3 | Find a book written by Sigrid Undset about Kristin? | Sigrid Undset Kristin |

Sigrid Undset Kristin |

| 4 | Find a document on stagecraft and lighting? | sceneteknikk lyssetting |

stagecraft lightning |

| 5 | Find a document on cyberbullying? | digital mobbing |

cyberbullying |

| 6 | Who is the author of the books about Albert and Skybert? | Albert Skybert |

Albert Skybert |

| 7 | Find a document about Norwegian recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize? | norske vinnere Nobels fredspris |

Norwegian recipients Nobel Peace Prize |

| 8 | Find a book on Knut Hamsun and Nazism? | Knut Hamsun Nazisme |

Knut Hamsun Nazism |

| 9 | Find a document about women in Algeria? | kvinner Algerie |

women Algeria |

| 10 | Find a play written by William Shakespeare? | William Shakespeare |

William Shakespeare |

Instructions and search tasks were given verbally, through sound files generated using speech synthesis. Participants were therefore not shown the spelling of query terms and misunderstandings caused by decoding errors were prevented. Before each task, the participants were shown an illustrative image and the task number, to allow them to follow their progress. The search behaviour was documented through screen recordings and mouse and keyboard event logs.

Equipment

The search experiments were run using SMI Experiment Center version 3.2.11, a visual stimulus presentation software, with the background screen recorder option turned on. The information was displayed on a 21’ Dell LED flat screen (resolution set to 1680 x 1050 pixels). For the search tasks, Windows Internet Explorer version 9 was used, with all functions related to prior use such as cookies or browsing history disabled.

Analysis

Data were analysed in SMI BeGaze version 3.2. Search logs provided data on the submitted queries and search times. Based on the logs, query lengths and spelling errors were calculated. Statistical analyses were performed using JASP version 0.8.6.0 (JASP Team, 2018). Pearson and Spearman correlations were used for continuous and ordinal variables, respectively.

Results

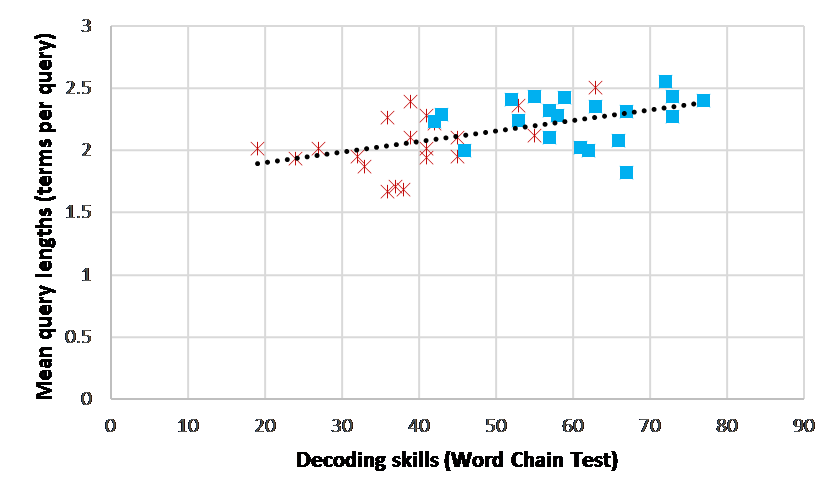

The first hypothesis (H1) assumes that decoding skills affect query lengths and the portion of misspelled queries. Figure 1 shows the mean query lengths plotted against the decoding skills of the participants represented by their Word Chain Test scores. Participants with official dyslexia diagnoses are represented with red crosses, blue squares are used to represent users from the control group. The Word Chain Test scores span a continuum of scores from 20 to 80. The mean query lengths, measured in the mean number of search terms, span a range from 1.6 to 2.5 terms per query. The participants with dyslexia and without dyslexia yield two clusters. However, three of the participants with a dyslexia diagnosis fall within the non-dyslexic cluster, while three participants from the control group are in the dyslexia cluster.

The plot reveals that individuals with high decoding skills tend to submit longer queries than individuals with lower decoding skills. The moderate positive correlation between mean query lengths and decoding skills is highly significant (r(40) = .531, p < .001). Similarly, a moderate positive correlation was found between minimum query lengths and the decoding skills (r(40) = .514, p < .001), where participants with lower decoding skills used fewer query terms in their shortest queries, compared to participants with higher decoding skills, which supports the first part of H1. No significant correlations were found between the decoding skills and the maximum number of query terms (r(40) = -.021, p = .900), the number of search terms during the first query (r(40) = .292, p = .067) or the number of search terms during the last query (r(40) = .242, p = .132).

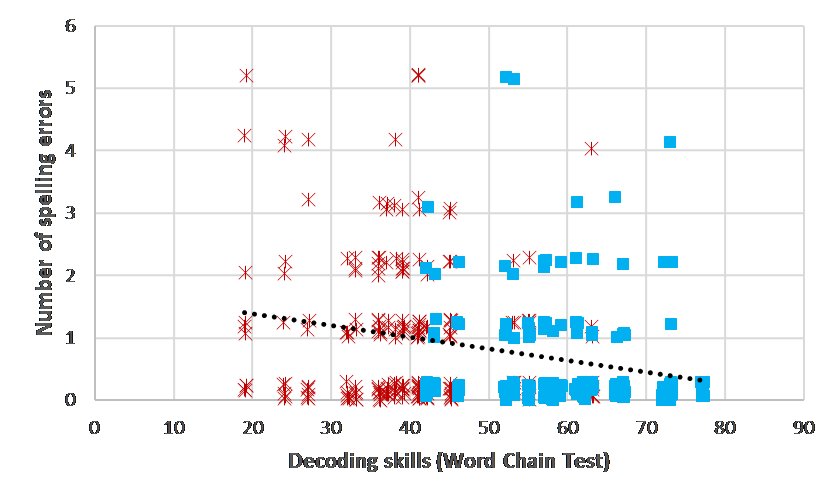

The second part of H1 regards misspelled queries. It was hypothesised that the portion of spelling errors would correlate with decoding skills, where low values on the Word Chain Test would cause a higher number of misspelled queries. Figure 2 shows a scatterplot of the relationship between the number of spelling errors and decoding skills. The results reveal a significant moderate negative correlation (rs(400) = -.279, p < .001). In other words, participants who scored high on the Word Chain Test made fewer spelling errors, while participants who scored low on the Word Chain Test exhibited more spelling errors. The results thus give support to the first hypothesis, namely that decoding skills may influence the number of spelling errors.

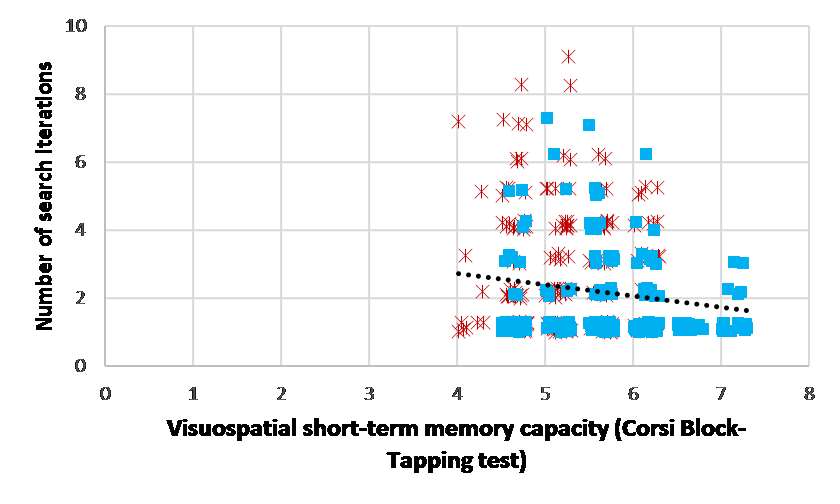

The second hypothesis (H2) suggests a relationship between short-term memory capacity and the number of iteration cycles. To test whether there is a relationship between the visuospatial short-term memory and the number of iterations to form a successful query, the results of the Corsi Block-Tapping Test were correlated with the number of queries made per search task (see Figure 3). The results show a negative and weak correlation between the visuospatial short-term memory capacity and the number of iterations needed to form a query (rs(400) = -.116, p = .020). Hence, participants with a lower short-term memory capacity needed to perform more iterations than participants with higher short-term memory capacities to solve a task. The need to perform multiple iterations were often caused by participants making mistakes and the number of iterations with mistakes in the Bibsys database also correlates with memory capacity (rs(400) = -.105, p = .036) as well as the number of attempts with Bibsys (rs(400) = -.105, p = .036). As a remedy, participants employed a strategy whereupon they used Google to form the Bibsys queries. The number of attempts using Google did not correlate significantly with memory capacity (rs(400) = -.059, p = .237), suggesting that the participants were more successful using Google than Bibsys.

To check for any relationships between verbal short-term memory and search patterns, the results of the Digit Span Test were correlated with the number of queries per task, the mean number of terms per query and search times. The results show that verbal short-term memory was significantly weakly and negatively correlated with search time (rs(400) = -.228, p < .001) and also weakly negatively correlated with number of queries (rs(400) = -.148, p = .003). However, the verbal short-term memory scores did not correlate with the mean number of terms per query (rs(400) = .095, p = .058). This means that participants who score highly on the Digit Span Test tended to need fewer iterations to complete a query, so needed less time to complete the query. Next, the score on the Digit Span Test did not seem to be related to how many terms the participants needed to form the queries. Consequently, both reduced visuospatial and verbal short-term memory seem to have caused a higher number of iterations, giving support to H2.

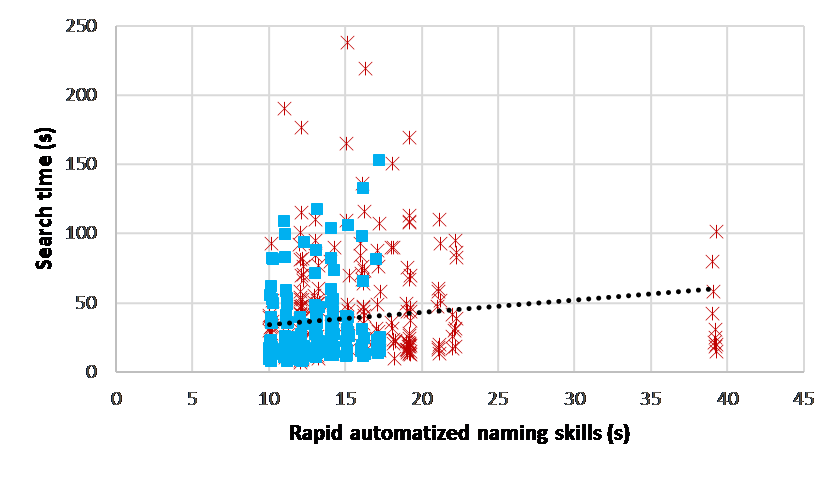

The third hypothesis (H3) stated that rapid automatised naming skills will affect query lengths and search times. To evaluate whether there were any relationships between rapid automatised naming skills, query lengths and search times, the Dot-card from the Stroop test was correlated against both mean query length per participant and query time for each task. The Dot-card test measured time taken to name colours and a low value therefore indicated better automatised naming skills than a larger value. No significant correlation was found between rapid automatised naming skills and query length for mean number of queries (r(40) = -.262, p = .103) or the first query for each search (r(400) = -.262, p = .282). However, a weak significant positive correlation was detected between the rapid automatised naming skills and the query time (r(400) = .132, p = .008). The scatterplot in Figure 4 shows that the control group had faster rapid automatised naming skills within a narrow range, while the participants with dyslexia exhibited a larger range of naming times. The plots also show that one user with dyslexia took much longer on the Dot-Card (approximately forty seconds) than the other tasks which all took less than twenty-five seconds.

One would expect queries with a higher number of terms to take more time to complete, however the correlation with query time may be related to the number of searches carried out as the mean number of queries is significantly and positively related to the rapid automatised naming skill with a weak correlation (rs(400) = -.140, p < .001).

Discussion

The first hypothesis (H1) suggests that decoding skills influence query lengths and the number of queries with spelling errors. The justification for this hypothesis is based on previous research claiming that dyslexia has a negative impact on searching in systems with a low tolerance for errors, making such systems inaccessible for users with dyslexia (Berget and Sandnes, 2015). In contrast, this effect was counteracted in systems with built in tolerance for errors (Berget and Sandnes, 2016). H1 assumes that users with impaired decoding skills will construct the shortest queries possible, to reduce the chances of misspelled search terms. Further, it is assumed that reduced decoding skills in general caused a higher number of erroneous queries, despite attempts to reduce query lengths.

Decoding skills seemed to correlate with mean query lengths and minimum number of search terms, but not the first and last query in each search. The interpretation of these results may be that reduced decoding skills primarily affected the intermediary queries, which partly confirmed the first part of H1. Participants with different levels of decoding skills may thus have started and finished their searches on approximately the same precision levels and therefore retrieved result lists with similar content regarding precision and recall. It is therefore plausible that decoding skills did not affect the result list content but may have had a significant impact on the query refinements.

The results from the Word Chain Test scores correlated with spelling errors, where users who scored highly on this test made fewer spelling errors. In contrast, participants with low scores on this test, made more errors. This finding supports the second part of H1.

Low scores on the Word Chain Test signal reduced decoding skills and a higher chance of dyslexia (Høien and Tønnesen, 2008), which also causes reading impairments, and may impact result list assessment. Consequently, users with reduced decoding skills may try to formulate the most precise queries possible to retrieve result lists with a high precision level, which may explain why the first and last queries had similar lengths for participants with different levels of decoding skills. However, due to the higher level of spelling errors, users with reduced decoding skills may need to reduce the lengths of the intermediate queries to locate the query terms that are incorrectly spelled, and then end the search with a revised, longer query to achieve high precision levels in the result lists. This strategy would cause a higher number of shorter queries, but retrieve more precise result lists, thus reducing the cognitive effort related to result list assessment. Further, this search approach could also explain the correlation found between decoding skills and mean query lengths, where users with reduced decoding skills had submitted a higher number of short queries. This assumption may be supported by the search logs, for instance, in a task locating documents about Knut Hamsun and Nazism:

Q1-1: knut hamsun nasismen, Q1-2: knut hamsun, Q1-3: knut hamsun nazismen

Another example can be found in a task finding books by Sigrid Undset about Kristin:

Q2-1: sigrid unset kirstin, Q2-2: sigrid unset, Q2-3: sigrid undset, Q2-4: sigrid undset kristin

One implication of the first hypothesis is that for users with reduced decoding skills, purposeful database search support would be to allow for errors in search terms, thus removing the need for all the reformulated intermediate queries, which would result in a more efficient search process. However, since users with dyslexia often make different types of errors to users without dyslexia (Moats, 1996), the search user interface should incorporate an advanced spell checker. Another possibility is to provide conversational search, where all the searching may be conducted through speech (Trippas, et al. 2017). Replacing the textual input with speech input may potentially remove spelling errors.

The second hypothesis (H2) assumes a relationship between short-term memory capacity and the number of iteration cycles, which would be in accordance with previous dyslexia research (MacFarlane, et al., 2012; MacFarlane, et al. 2017). However, while previous research addressed result list assessment, this study investigates query formulations. Results showed that both visuospatial short-term memory and verbal short-term memory correlated with number of queries, where people with reduced memory capacity needed more iterations to complete a search task, which supports H2.

Implications of H2 is that short-term memory capacity seems to play an important role in query formulation. More iterations caused by reduced short-term memory capacity may be seen in the occurrence of repeated identical queries. One example was found in a task searching for stage techniques and lights, where the second and third queries were identical:

Q3-1: scenetenkikk lysetting, Q3-2: scenetenkikk lyssetting, Q3-3: scenetenkikk lyssetting (…)

Another example is a participant searching for cyber bullying, where the two first queries were identical:

Q4-1: mobbing digitalt, Q4-2: mobbing digitalt, Q4-3: mobbing digital

The same strategy was found when looking for Norwegian winners of the Nobel Peace Prize, again with the two first queries identical:

Q5-1: nobels fredspris norsk, Q5-2: nobels fredspris norsk, Q5-3: norsk vinnere av nobels fredspris, Q5-4: norske vinnere nobels fredspris

One may ponder whether the repeated attempts at the same query could be caused by a lack of appropriate feedback from the search system or visibility of such feedback. Given more adequate feedback, in particular clues to how the system interprets the query, the users should be able to diagnose the problem and make the appropriate query refinements.

The third hypothesis (H3) implies that rapid automatised naming skills relate to query lengths and search times. The basic assumption is that difficulties remembering the words to include in a query will manifest itself through shorter queries, but also longer search times because it will take participants longer to come up with the correct term. No significant correlation could be found between random automatised naming skills and overall query lengths or query lengths in the first query. However, there was a weak correlation with query times, partly confirming H3.

These results may imply that rapid automatised naming does not have a great effect on query formulation. However, the results may also be caused by the experimental design. In this study, the participants were given predefined tasks, which included potential query words that may have reduced this effect because the participants did not have to come up with all the query terms themselves. This is an issue that needs to be researched more thoroughly in experiments with more vaguely formulated tasks, for instance by using the simulated work tasks method (Borlund, 2000) or where users are observed in their everyday information searching, where search tasks are based on their actual needs.

Difficulties remembering words during query formulation may potentially impact query formulation, since short and/or imprecise queries may generate result lists with many irrelevant results. It is claimed that users with dyslexia generally find result list assessment challenging (MacFarlane, et al. 2010; MacFarlane, et al. 2012). Assisting users in formulating more precise queries may therefore be potentially helpful. Another issue is helping users to formulate queries by finding appropriate terms, for instance by suggesting terms (autocomplete). A well-developed thesaurus consisting of subject headings that allows the user to navigate towards the proper terms is another potentially helpful search aid, a technique already applied in some systems, for instance Medline. However, such search behaviour would also be potentially time consuming, and consequently not enhance the search process. Moreover, it would require reading through many potentially similar query suggestions, which might be demanding for people with reading impairments, since decoding errors might result in using irrelevant or faulty query suggestions.

Another option is to combine chat with information retrieval, where the system tries to predict information needs before they arise. For instance, based on users discussing issues such as going to the cinema or finding a restaurant, the system can retrieve and present potentially relevant information before the user has even started to think specifically about an information need or inputting a query (Avula, Chadwick, Arguello and Capra, 2018). Providing users with visual result lists while inputting the query may also be helpful, to give the user some idea of whether the correct query terms have been identified.

Conclusion

The research question was: which cognitive skills typically affected by dyslexia are needed to conduct successful queries? Three characteristics were investigated, namely decoding skills, short-term memory capacity and rapid automatised naming. The results suggest that cognitive skills may have an impact on query formulation in different ways, and that a broad spectrum of cognitive skills are needed for successful query formulation.

Decoding skills correlated with query lengths and spelling errors, which affect the ability to retrieve results in systems with high demands for correct spelling. Further, these skills will influence the number of short queries needed to find proper spelling of terms. Short-term memory capacity correlated with the number of attempts to complete a task. Consequently, people without reduced short-term memory will need fewer searches to solve tasks, and therefore be more efficient information searchers than people with reduced short-term memory. Rapid automatised naming correlated with query times, and again users with highly developed rapid automatised naming skills may therefore conduct more efficient searches.

These cognitive measures are often impaired in users with dyslexia and may explain why dyslexics find query formulation challenging. However, these cognitive skills may also vary among other users without a dyslexia diagnosis, for instance due to age, temporary or chronic illness, divided attention, stress or fatigue. Search user interface developers should therefore consider a wider cognitive profile of users to support successful query formulations and information retrieval.

It is appropriate to question the design of the traditional text search interfaces and apply new technologies and methods for improved information retrieval. While traditional systems place a substantial cognitive workload on the user, it seems a promising direction to transform search into more of a conversation between the user and the system. Consequently, by taking steps to improve the experience of search interfaces for individuals with dyslexia the search experience is likely to be improved for all users.

Acknowledgements

The project was financially supported by the Norwegian ExtraFoundation for Health and Rehabilitation through EXTRA funds grant 2011/12/0258. The authors are grateful to the volunteering students and Dyslexia Norway for help recruiting participants, and to the reviewer and copyeditor for their contributions.

About the authors

Gerd Berget, PhD, is an associate professor at Department of Archivistics, Library and Information Science at Oslo Metropolitan University. Her research focus on universal design, interactive information retrieval and dyslexia. She can be contacted as gerd.berget@oslomet.no.

Frode Eika Sandnes, PhD, is a professor at the Department of Computer Science at Oslo Metropolitan University. His research interests include human computer interaction, universal design and pattern matching. He can be contacted at frode-eika.sandnes@oslomet.no.

References

- Al-Wabil, A., Zaphiris, P. & Wilson, S. (2007). Web navigation for individuals with dyslexia: an exploratory study. In Constantine Stephanidis, (Ed.). Universal Access in Human Computer Interaction. Coping with Diversity. 4th International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction, UAHCI 2007, Held as Part of HCI International 2007, Beijing, China, July 22-27, 2007, Proceedings, Part I (pp. 593-602). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 4554). Retrieved from http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/1051/1/1406_final.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P15uNPf).

- Appert, D. & Truillet, P. (2015). Influence of the presentation of words for dyslexic readers. In Proceedings of the 27th Conference on l'Interaction Homme-Machine, Toulouse, France (article no. 33). New York, NJ: ACM. Retrieved from https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01219096/document. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P1jHpM2).

- Appert, D. & Truillet, P. (2016). Impact of word presentation for dyslexia. In Jinjuan Heidi Feng & Matt Huenerfauth (Eds.), Proceedings of the 18th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Reno, NV, USA (pp. 265-266). New York, NJ: ACM. Retrieved from https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01475019/document. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P1yqDi3).

- Avula, S. Chadwick, G., Arguello, J. & Capra, R. (2018). SearchBots: user engagement with ChatBots during collaborative search. In Chiraq Shah & Nicholas Belkin (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Human Information Interaction & Retrieval, New Brunswick, NJ, USA (pp. 52-61). New York, NJ: ACM. Retrieved from https://ils.unc.edu/~jarguell/AvulaCHIIR2018.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P2QX26N ).

- Baddeley, A. (2003). Working memory and language: an overview. Journal of Communication Disorders, 36(3), 189-208.

- Baeza-Yates, R. & Rello, L. (2011). Estimating dyslexia in the web. In Leo Ferres (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Cross-Disciplinary Conference on Web Accessibility, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India (article no. 8). New York, NJ: ACM. Retrieved from http://www.ra.ethz.ch/CDStore/www2011/W4A/p12.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P2bI1tE).

- Bawden, D. & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of information: overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 180-191.

- Beidas, H., Khateb, A. & Breznitz, Z. (2013). The cognitive profile of adult dyslexics and its relation to their reading abilities. Reading and Writing, 26(9), 1487-1515.

- Berget, G. & Sandnes, F. E. (2015). Searching databases without query-building aids: implications for dyslexic users. Information Research, 20(4), paper 689. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/20-4/paper689.html#.XGPFkqB7nt4. (Archived by WebCite® athttp://www.webcitation.org/769MqlvOd).

- Berget, G. & Sandnes, F. E. (2016). Do autocomplete functions reduce the impact of dyslexia on information‐searching behavior? The case of Google. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(10), 2320-2328.

- Berners-Lee, T. & Cailliau, R. (1992). World-Wide Web. The Conference on Computing in High Energy Physics 92, Annecy, France (pp. 69-74). Retrieved from https://cds.cern.ch/record/245440/files/p69.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P2z4jvY).

- Borlund, P. (2000). Experimental components for the evaluation of interactive information retrieval systems. Journal of Documentation, 56(1), 71-90.

- Brand-Gruwel, S., Wopereis, I. & Vermetten, Y. (2005). Information problem solving by experts and novices: analysis of a complex cognitive skill. Computers in Human Behavior, 21(3), 487-508.

- Bremner, J. D., Randall, P., Scott, T. M., Capelli, S., Delaney, R., McCarthy, G. & Charney, D. S. (1995). Deficits in short-term memory in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Psychiatry Research, 59(1), 97-107.

- Chen, L. & Chua, C. (2013). Interactive interface for query formulation. In Haifeng Sheng, Ross Smith, Jeni Paay, Paul Calder & Theodor Wyeld (Eds.) Proceedings of the 25th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference: Augmentation, Application, Innovation, Collaboration, Adelaide, Australia (pp. 507-510). New York, NY: ACM.

- Cole, L., MacFarlane, A. & Buchanan, G. (2016). Does dyslexia present barriers to information literacy in an online environment? a pilot study. Library and Information Research, 40(123), 24-46.

- Cucerzan, S. & Brill, E. (2004). Spelling correction as an iterative process that exploits the collective knowledge of web users. Paper presented at the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, EMNLP 2004 A meeting of SIGDAT, a Special Interest Group of the ACL, held in conjunction with ACL 2004, Barcelona, Spain.

- Drabenstott, K. M. & Weller, M. S. (1996). Handling spelling errors in online catalog searches. Library Resources & Technical Services, 40(2), 113-132.

- Duan, H. & Hsu, B.-J. (2011). Online spelling correction for query completion. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on World Wide Web, Hyderabad, India (pp. 117-126). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.205.8862&rep=rep1&type=pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P3TczAM).

- Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2004). Digital literacy: a conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 13(1), 93-106.

- Fan, M. & Antle, A. N. (2015). Tactile letters: a tangible tabletop with texture cues supporting alphabetic learning for dyslexic children. In Bill Verplank & Wendy Ju (Eds.), Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Stanford, CA, USA (pp. 673-678). New York, NY: ACM.

- Fan, M., Antle, A. N. & Cramer, E. S. (2016). Exploring the design space of tangible systems supported for early reading acquisition in children with dyslexia. In Saskia Bakker, Caroline Hummels & Brygg Ullmer (Eds.), Proceedings of the TEI '16: Tenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, Eindhoven, Netherlands (pp. 689-692). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from http://www.westlakeimage.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/FanAntleCramer_TEI16_GSC.pdf . (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P3qRu2P).

- Ferrer, E., Shaywitz, B. A., Holahan, J. M., Marchione, K. & Shaywitz, S. E. (2010). Uncoupling of reading and IQ over time: empirical evidence for a definition of dyslexia. Psychological Science, 21(1), 93-101.

- Gohar, A., Adams, A., Gertner, E., Sackett-Lundeen, L., Heitz, R., Engle, R., . . . Bijwadia, J. (2009). Working memory capacity is decreased in sleep-deprived internal medicine residents. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 5(3), 191-197.

- González, L. F. (2017). Combining visual and textual languages for dyslexia. In Gail C. Murphy (Ed.), Proceedings Companion of the 2017 ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Systems, Programming, Languages, and Applications: Software for Humanity, Vancouver, BC, Canada (pp. 4-6). New York, NY: ACM.

- Gregor, P. & Newell, A. F. (2000). An empirical investigation of ways in which some of the problems encountered by some dyslexics may be alleviated using computer techniques. In Proceedings of the Fourth International ACM Conference on Assistive Technologies, Arlington, VA, USA (pp. 85-91). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2Vgx08b. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P4Ajx6o).

- Gwizdka, J. (2010). Distribution of cognitive load in web search. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(11), 2167-2187.

- Hearst, M., Elliott, A., English, J., Sinha, R., Swearingen, K. & Yee, K.-P. (2002). Finding the flow in web site search. Communications of the ACM, 45(9), 42-49.

- Helland, T. & Asbjørnsen, A. (2004). Digit span in dyslexia: variations according to language comprehension and mathematics skills. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 26(1), 31-42.

- Hill, H. (2013). Disability and accessibility in the library and information science literature: a content analysis. Library & Information Science Research, 35(2), 137-142.

- Høien-Tengesdal, I. & Tønnessen, F. E. (2011). The relationship between phonological skills and word decoding. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 93-103.

- Høien, T. & Tønnesen, G. (2008). Ordkjedetesten [The Word Chain Test]. Bryne, Norway: Logometrica.

- Ingwersen, P. (1996). Cognitive perspectives of information retrieval interaction: elements of a cognitive IR theory. Journal of Documentation, 52(1), 3-50.

- JASP Team. JASP (Version 0.9). 2018.

- Kane, M. J., Hambrick, D. Z., Tuholski, S. W., Wilhelm, O., Payne, T. W. & Engle, R. W. (2004). The generality of working memory capacity: a latent-variable approach to verbal and visuospatial memory span and reasoning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(2), 189-217.

- Lervåg, A. & Hulme, C. (2009). Rapid automatized naming (RAN) taps a mechanism that places constraints on the development of early reading fluency. Psychological Science, 20(8), 1040-1048.

- Li, S-C., Schmiedek, F., Huxhold, O., Röcke, C., Smith, J. & Lindenberger, U. (2008). working memory plasticity in old age: practice gain, transfer, and maintenance. >Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 731-742.

- MacFarlane, A., Al-Wabil, A., Marshall, C. R., Albrair, A., Jones, S. A. & Zaphiris, P. (2010). The effect of dyslexia on information retrieval: a pilot study. Journal of Documentation, 66(3), 307-326.

- MacFarlane, A., Albrair, A., Marshall, C. R. & Buchanan, G. (2012). Phonological working memory impacts on information searching: an investigation of dyslexia. In Jaap Kamps & Wessel Kraaji (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th Information Interaction in Context Symposium, Nijmegen, The Netherlands (pp. 27-34). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/4493/1/dyslexia-memory-search-oa.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P4UhepR).

- MacFarlane, A., Buchanan, G., Al-Wabil, A., Andrienko, G. & Andrienko, N. (2017). Visual analysis of dyslexia on search. In Ragnar Nordli & Nils Pharo (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Conference Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, Oslo, Norway (pp. 285-288). New York, NY: ACM.

- Mammarella, I. C., Pazzaglia, F. & Cornoldi, C. (2008). Evidence for different components in children's visuospatial working memory. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26(3), 337-355.

- Miniukovich, A., Angeli, A. D., Sulpizio, S. & Venuti, P. (2017). Design guidelines for web readability. In Oli Mival (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Edinburgh, United Kingdom (pp. 285-296). New York, NJ: ACM. Retrieved from http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/30210/1/p285-miniukovich.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P4r2H0f).

- Moats, L. C. (1996). Phonological spelling errors in the writing of dyslexic adolescents. Reading and Writing, 8(1), 105-119.

- Mueller, S. T. (2010). The Psychology Experiment Building Language, Version 0.11. Retrieved from http://pebl.sourceforge.net. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/769NDN2Fn).

- Neuhaus, G., Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J. & Carlson, C. D. (2001). Measures of information processing in rapid automatized naming (RAN) and their relation to reading. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 78(4), 359-373.

- Norton, E. S. & Wolf, M. (2012). Rapid automatized naming (RAN) and reading fluency: implications for understanding and treatment of reading disabilities. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 427-452.

- Oliveto, R., Gethers, M., Poshyvanyk, D. & Lucia, A. D. (2010). On the equivalence of information retrieval methods for automated traceability link recovery. In Giuliano Antoniol, Keith Gallagher & Pedro Rangel Henriques (Eds.) Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 18th International Conference on Program Comprehension (pp. 68-71). Washington, DC: IEEE. Retrieved from http://www.cs.wm.edu/semeru/papers/IR01.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P5TucJQ).

- Ouilhet, H. (2010). Google sky map: using your phone as an interface. In Marco de Sá & Luís Carriço (Eds.), Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, Lisbon, Portugal (pp. 419-422). New York, NY: ACM

- Pagulayan, K. F., Busch, R. M., Medina, K. L., Bartok, J. A. & Krikorian, R. (2006). Developmental normative data for the Corsi Block-Tapping task. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 28(6), 1043-1052.

- Perez, T. M., Poncelet, M., Salmon, E. & Majerus, S. (2015). Functional alterations in order short-term memory networks in adults with dyslexia. Developmental Neuropsychology, 40(7-8), 407-429.

- Rello, L., Bayarri, C., Otal, Y. & Pielot, M. (2014). A computer-based method to improve the spelling of children with dyslexia. In Sri Kurniawan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility, Rochester, NY, USA (pp. 153-160). New York, NY: ACM.

- Sahib, N. G., Tombros, A. & Stockman, T. (2012). A comparative analysis of the information‐seeking behavior of visually impaired and sighted searchers. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(2), 377-391.

- Sandnes, F. E., Tan, T. B., Johansen, A., Sulic, E., Vesterhus, E. & Iversen, E. R. (2012). Making touch-based kiosks accessible to blind users through simple gestures. Universal Access in the Information Society, 11(4), 421-431.

- Schneider, N., Dorr, M., Pomarjanschi, L. & Barth, E. (2011). A gaze-contingent reading tutor program for children with developmental dyslexia. In Stephen N. Spencer (Ed.), ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on Applied Perception in Graphics and Visualization (APGV '11), Toulouse, France (pp. 117-117). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2NszygT (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P7MPYJt).

- Shneiderman, B., Byrd, D. & Croft, B. (1997). Clarifying search: a user-interface framework for text searches. D-Lib Magazine, 3(1), 1-17.

- Snowling, M. J., Gallagher, A. & Frith, U. (2003). Family risk of dyslexia is continuous: individual differences in the precursors of reading skill. Child Development, 74(2), 358-373.

- Sparks, R. L., Patton, J., Ganschow, L., Humbach, N. & Javorsky, J. (2008). Early first-language reading and spelling skills predict later second-language reading and spelling skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(1), 162-174.

- Strauss, E., Sherman, E. M. S. & Spreen, O. (2006). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. Oxford: Oxford Press.

- Trippas, J. R., Spina, D., Cavedon, L. & Sanderson, M. (2017). How do people interact in conversational speech-only search tasks: a preliminary analysis. In Ragnar Nordli & Nils Pharo (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Conference Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, Oslo, Norway (pp. 325-328). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from http://www.marksanderson.org/publications/my_papers/chiir097s-trippasA.pdf. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76P7h69oi).

- Vandierendonck, A., Kemps, E., Fastame, M. C. & Szmalec, A. (2004). Working memory components of the Corsi blocks task. British Journal of Psychology, 95(1), 57-79.

- Venturini, G. & Gena, C. (2017). Testing web-based solutions for improving reading tasks in students with dyslexia. In Fabio Paternò & Lucio Davide Spano (Eds.), Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter, Cagliari, Italy (article no. 12). New York, NY: ACM.

- Wang, X. J., Zhang, L., Li, X. & Ma, W. Y. (2008). Annotating images by mining image search results. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 30(11), 1919-1932.

- Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270.