The assemblage of repository and museum work in archaeological curation

Sarah A. Buchanan.

Introduction. Archaeological collections comprise both artefacts and the documentation generated about those artefacts. The involvement of multiple datasets and professions suggests a complex infrastructure for archaeological curation. The study investigated whether curation work occurs outside of the museum exhibition setting, and how any data practices of non-museum individuals impact the practice of archaeological curation.

Method. Data were collected over the course of sixty-five hours of observations and interviews with ten repository and museum professionals.

Analysis. Fieldnotes and audiovisual recordings were subjected to an open coding analytical approach which eventually produced four constructed categories of work.

Results. The variance between the contributions of repository managers and museum professionals lies in different approaches to aggregating and assembling data formats, quality, and closure.

Conclusions. There are key points of data transition between the repository and museum professions – such as physical sorting by material class and quantity; item- and collection-level condition reporting; and writing an integrative and engaging narrative – where future information research might continue in focus.

Introduction

The unceasing flow of archaeological materials out of excavations and into curatorial repositories, museum vaults, and personal storage spaces is a fact acknowledged by archaeologists and information workers alike. Given that numerous government studies (Banks, Lee and Engel, 2016, p. 164; Altschul, 2016; Hitchcock, 1994; Jelks, 1989) have now precisely enumerated the scale of that flow, in reports, projects' digital files, artefacts, and artefact repositories respectively, it is not surprising to see evidence of cross-disciplinary collaboration by information science, museum studies, and even archaeological researchers around issues of collection management. Examples include the long-running Summer Institute in Museum Anthropology (SIMA) (Nichols and Lowman, 2018), the Archives of Archaeological Interest map (Kirakosian and Bauer-Clapp, 2017), the creation of teaching collections for graduate coursework (Krmpotich, 2015), and Wingfield's (2017) refresh of museum archaeology, not to mention public engagement on issues of the same, e.g., with the Penn Museum lending multiple objects for the well-attended travelling exhibition Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology (Berlin, 2015; Thurlow, 2011). Although awareness of collection management issues in archaeology is wide (liberated from only academic pursuits), the problem of providing expert preservation and access to excavation materials does remain both pressing and unresolved. It exceeds archaeology and concerns several cognate professions.

Wingfield sees museums as complex, vibrant sites of original knowledge production, asserting that collections 'need to be reconsidered as a mode of assemblage (and crucially reassemblage) that remains fundamental to many archaeological projects and practices' (2017, p. 595). The argument is premised on the assertion of a problematic view among some archaeologists, as in Lucas (2012, p. 245), that the museum's purpose is wholly separate from archaeology, to wit: that excavation materials are already 'the archive,' regardless of whether any work by information professionals has yet been carried out on those materials. This paper asks, is museum work separate from or a part of archaeological work? Specifically we take up Wingfield's assemblage concept and apply it not to a collection, but to the activity and the project of archaeological curation. We see archaeological curation as an assemblage of several professions. The Lucas view does little to recognise the added value of curatorial repository managers, and, by perpetuating favour toward excavation, is patently immune to Wingfield's exploration of just how museum settings truly offer new insights and ultimately strengthen the archaeological endeavour. More relevant for our purposes, such an outlook conflates the museum setting with a jumble of not-exclusively-museum practices, failing to differentiate between the work supporting particular archaeological collections that occurs in U.S. statewide curatorial repositories (whose work is to ensure long-term preservation) and that in museums (whose work is to craft an engaging exhibition and display of objects). The purpose of this study is in fact to clarify the distinct contributions of those two areas of information work, adhering to their respective bases of pedagogy and professional skillsets.

Disciplinary incentives have undervalued curation work in the field of archaeology, yet the resulting collections continue to take up precious physical space and land. Consequently, curation work now lies squarely in the fields of information, museum studies, and heritage management. Information researchers see that data of all types are endangered when audiences do not know they exist, or when the data cannot be contextualized without associated documentation (Allen, Stewart and Wright, 2017). Information workers confront such situations and raise awareness via the theoretical outcome of legitimization (Panella, 2015), but others may mistakenly lob fault therein when in fact the actual information loss occurred decades or centuries prior in the field or laboratory. Regardless, when applied to archaeological collections, such absence effectively constitutes 'suppressed provenance' (Brodie, 2011). Considering the centrality of archaeological materials to our understanding of ourselves in society, without provenance documentation we perpetuate inequities in how history is presented and lessen the opportunities for all communities to recognize themselves in museum narratives.

Why archaeological curation: definition and renascence

Archaeological curation is the management of artefacts and associated documentation after discovery in an excavation. It is an activity that occurs in the context of particular frameworks for archaeological conservation that are regulated at the country, state, and local levels, and, as Kersel (2015a, p. 42) notes, curation implies 'careful stewardship' that is proactive. Essential works such as Curating archaeological collections (Sullivan and Childs, 2003), Childs (1995, p. 11), and Merriman and Swain (1999, p. 249) have raised initial awareness and established the scope and nature of archaeological curation. We have a broad sense of where archaeological curation takes place across the United States, since a 1996 conference sponsored by the Interagency Federal Collections Alliance first brought together curators from U.S. federal agencies and non-federal repositories to discuss collections care issues. A resulting survey conducted in 1997-98 was arguably the first to systematically examine the work of American repositories, and several since then have focused the line of inquiry on curation fees (Childs and Kagan, 2008). Currently over 200 repositories are charged with accessioning archaeological collections (after private or public excavation activity) but they vary widely in their mission, depending on whether one serves as the primary repository for an entire state or region, or has a smaller scope focused on a few sites or university-sponsored projects. The surveys conducted in 1997/98, 2002, 2007/08, and 2010, the latter by Watts (2011, p. 3), revealed progressively more nuanced data about how repositories support the long-term care and management of archaeological collections. Our knowledge gained from such work over the past two decades centers around two levels of understanding: one (at that of the repository institution) regarding the skills in demand for carrying out collection curatorship and stewardship, and another (disciplinarily) on the connectedness of archaeological curation repositories to public-facing museums. With this foundational research at hand, the challenge for researchers today lies less in proffering ways to improve curatorial and museum practice, than in examining the distribution and transfer activities that shape how archaeological collections come into being.

In addition to the government studies noted in the Introduction, visitors' perception as attested to by Heyman (1997), leader of the Smithsonian Institution from 1994 to 1999, is that American repositories, or attics as they have been derided, have too many artefacts with too little documentation, and for some reason museums are not telling enough artefacts' stories. The problem is acute in England as well, where two governmental bodies, Historic England and Arts Council England, recently developed an action plan to address sustainable management of archaeological collections (Historic England, 2018), and the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists, Archaeological Archives Group (CIfA AAG) , since its formation in 2012, has held an annual general meeting on the topic. More broadly we see the contention of a curation crisis in the archaeological professional literature's own tropology. To ascertain and document the problem, Jelks (1989) visited thirty-four American repositories in eight states and determined that curatorial practices at most of the repositories did not meet acceptable standards. Incontrovertibly, the curation crisis is real, and archaeologists have been using the term earnestly since the late 1970s.

Archaeological collections' volume grew so rapidly in the later 20th century that archaeologists themselves labelled the phenomenon a curation crisis to capture the accumulation of material from excavations and lack of appropriately clear documentation to help make sense of the material. Shortly after the enactment of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the number of federal- and state-mandated archaeological projects sharply rose, yielding an equally sharp rise in the collection volume being sent to repositories for curation. Many U.S. repositories, such as those at university and state museums, had until then provided curatorial services at no cost to the collection owners, whether the materials came from federal, state, local, or private land. As one scholar wrote of academic archaeology in Missouri at that time, 'When a project ended, in would come boxes and boxes of stuff' (Marquardt, in Childs, 2004, p. 169). As another example, the Florida Museum of Natural History stores collections from more than 1,600 Florida sites, but curators note that federal regulations do not apply to projects on private land and those resulting collections are orphaned and very often homeless (Milanich, 2005). Arguably, most of these artefacts are still effectively underground, as if they were never excavated. Yet rising numbers of students, professionals, and museum visitors are requesting access to archaeological collections for scholarly research (Nelson and Shears, 1996, p. 34).

Renascence is the revival of something that has been dormant (Renascence, 2018). It happens to also be the title of a poem by American poet Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) that grapples with the barriers of constricted physical space. Renascence captures both the present condition as well as the more aspirational goals of our continuing work curating archaeological collections – work that strives to overcome space issues to provide greater and broader access to our hidden stories, biographies, and heritage. Innumerable archaeological collections have not seen the light of day for decades since excavation. Yet if we extended the digital convergence ethos pervasive across the information field to archaeology collections, we might see public audiences telling more artefacts' stories using provenance data; taking the forms of participatory catalogue records, exhibit labels, and exhibition checklists (Marty, 2009; Iliadis and Russo, 2016; Bates, Goodale and Lin, 2015). Ongoing conversations in the museum studies field about curating, managing, and presenting archaeological collections, which acknowledge an essential interdisciplinarity, inform and contribute to the research presented here.

Archaeological curation as assemblage

The concept of assemblage informs our thinking about the two information settings being considered here: repositories and museums. As stated in the Introduction, repositories are essentially and structurally focused on ensuring long-term preservation, while museums uniquely focus on displaying and exhibiting objects. They are separate types of institutions, given the scope differences between the 200 statewide repositories (Watts, 2011) and the estimated 35,000 museums in the U.S.A. (Bullard, 2014). Assemblages, understood here as systems that collect an individual set of practices into a set or collective whole, are a particularly helpful concept for comprehending complex, dynamic sociocultural spheres of activity. One system is in turn part of ever larger wholes, and a researcher can put several systems together to critically examine any number of social configurations or phenomena. Here we view the archaeological curation assemblage as one that is itself made up of the professional systems of repository work and museum work. Our assemblage is never static: artefacts, tools, individuals, and social groups change over time and space (Srnicek, 2007, p. 54) – but it does reliably consist of heterogenous elements that relate to and interact with one another as part of a professional system'. Heterogeneity, indeed, may be the assemblage's most consistent quality, and here we attend to the heterogenous information work that we can better recognise as repository or museum practice. First we briefly consider the historical connections between museums, archaeology, and storage (Kersel, 2015b), and more generally, the creation of archaeological information.

At the start of the 20th century, museum leaders in the U.S. began to shift collective focus towards public education and exhibition; universities and other organizations stepped forward to support basic archaeological research and sponsor excavation projects. That period began to establish a foundation for the resulting curation crisis, as collection-building became separated from collections care and management. The U.S. government also enacted federal historical preservation laws for the first time, beginning with the Antiquities Act of 1906 (Phelan, 1993, p. 63). The federal government supervised many large-scale dam and reservoir, highway, canal, and other construction projects across the U.S.A. in the 1920s, and began supporting salvage archeology programmes (Fagette, 1996). The Works Progress Administration projects of the 1930s expanded such programmes, which continued for some time after the end of World War II. Projects carried out in the American Southeast, Midwest, and Southwest kept excavated materials, some prehistoric in age, steadily flowing into the rooms of facilities, warehouses, and repositories. Museums accessioned literally millions of archaeological artefacts recovered from public and private lands, in a variety of material formats.

Leading up to the recognition of a curation crisis in the late 1970s, curation efforts were stymied by archaeological incentives toward excavation rather than collection analysis, or 'making versus caring' (Marquardt, Montet-White, and Scholtz, 1982, p. 409; Sullivan and Childs, 2003). Several initiatives have since drawn positive attention to the problem and point to continued collaborative potential across the archaeology, museum, and information science fields. Scholars examine international curation standards from the perspectives of the United Kingdom and Europe, Switzerland, Germany, Canada, and the states of Maryland, Wisconsin, and Arizona in a special issue sparked by a Society for American Archaeology conference session in 2008 (see Perrin, 2009, p. 9). Ensuing special issues of Heritage Management and the Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies revisit the curation crisis with the gaze of experience, asserting that the situation remains pressing (Childs, 2010, p. 155; Kersel, 2015a, p. 42). In their work paralleling the open storage and whole-drawer imaging prototypes mentioned earlier, Singh and Brusius (2018) led a series of workshops that critique the practice and politics of collection storage, and more recent research groups such as Active Collections and the Jenks Society pursue examinations of the imbalances of physical space with human resources (Lubar, Rieppel, Daly and Duffy, 2017). As we acknowledge the complex environment underpinning the work of archaeological curation, we also must acknowledge varying terminologies in use to describe the data about artefacts. Different scholars have termed such archival data 'associated records' (Sullivan and Childs, 2003, p. 87), 'excavation records' and 'archaeological archives' (Swain, 2007; Kirakosian and Bauer-Clapp, 2017): here we use documentation. Concerned as it is with both artefacts and documentation, curation (a word with etymology from the Latin root cura, to care or concern), has in recent years escaped both its historical attachment to art museum practice and its conceptualization by Lewis Binford to refer to people's use of handmade tools (Lee and Tibbo, 2011, p. 123): as one newspaper has announced, 'everybody's a curator' (Johnston, 2014). The pervasiveness of curation in our daily parlance has arguably slighted the added value that trained curators bring to the task of curation.

Problem statement

Archaeological curation remains beset by a problem of inefficiencies in coordinating narrowly-purposed professional and human resources towards broader, shared preservation and access goals for collections. Distinct bundles of disciplinary traditions and pressures that best serve the professionals, rather than a collection, have stymied our overall progression from shared contact to reaching full research and exhibition potential with most collections. The bundles' real persistence in archaeological curation needs to be more fully anticipated at all stages. The problem is less one of four competing visions than it is of failure to accede equal footing across four fully-developed and distinct professional incentive systems altogether impeding rather than fostering interdisciplinary collaboration (a role I will suggest for information researchers). The present research sought to investigate the problem of archaeological curation by asking and then examining where it happens. Provenance is the history of an object from the moment of its excavation to the present (often in a museum); provenance research, similarly, is the gathering of data from different points in time and their compilation in the form of a complete narrative. We in this study examine the provenance not of one object, but of collections that have arrived at the museum exhibition stage: where were they before the museum? What documentation accompanied? Expanding on the premise in the subtitle of Sullivan and Childs' 2003 book, 'from the field to the repository,' this study considered what kind of curation activities might occur at and between the multiple settings objects temporarily traverse, once excavated in a controlled archaeological dig, before being made accessible to researchers or the public. We identified four such settings based on museum accession records describing objects' provenance: an excavation site, conservation laboratory, curatorial repository, and exhibiting museum. This paper will focus exclusively on the latter two professional settings (those closest to the eventual presentation of object information to public audiences) articulating how the repository and the museum fulfil different roles in the path. This study takes an interest in professions and where they intersect, based on an understanding that archaeological curation is a complex and interdisciplinary endeavour. It will argue that successful collections management in archaeology will require members of four professions – but especially repositories and museums – to recognise how disciplinary data practices and norms impact the research potential and eventual public interaction with archaeological heritage. Information is lost at problematic points of data handoffs along the path from excavation to display. By comprehending exactly where archaeological curation work appears to break down, we can better position future information professionals to proactively address particular transition points. Improved artefact visibility and knowledge about their provenance will grow audiences and advocates for archaeological activities.

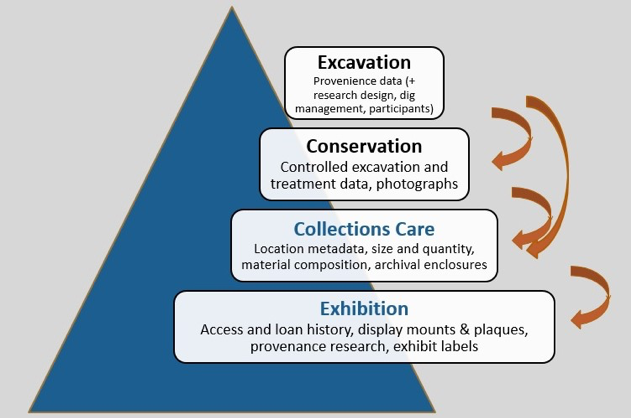

Archaeological curators remain a loosely-networked scholarly community even though they shoulder significant responsibilities (see Watts, 2011, p. 3). In the absence of 'a professional organization of archaeological repositories' (Childs, personal communication 31 March 2016), we see that archaeologists and museum curators, two professions, are contesting the practice of curation (the care, protection, and preservation of archaeological collections) and attempting to claim it as their own. The boldest evidence on the archaeologists' side is by Sullivan and Childs (2003), who outline a practical framework for conducting curation as a faceted process, with hierarchical procedures meant to guide collections along the path from the field to the repository. Barker (2010, p. 300) and Pearce (1990) on the other hand argue that the collections care duties that museum curators carry out make archaeological curation their purview. Yet curation activities are in fact pervasive across both those professions as well as two others (conservators, and the fourth, which this study closely considers, are repository managers who are not in a museum setting). Figure 1 summarises the four communities involved in this practice and the activities for which each is responsible (the arrows, which depict data handoffs, are addressed in detail in the Discussion).

The next sections argue that archaeological curation is the assemblage of multiple systems of work, but instead of uniformly-trained curators fulfilling the responsibilities of curation, we have across the U.S. many people (most not identifying as curators) involved in object handling. The activities each of these participants perform may not even, in the end, constitute work products that a museum curator would find useful, but are rather done to meet short-term data processing goals in their discipline.

Methods

Data collection occurred at two public institutions with state-wide responsibility for managing archaeological collections – a repository and a museum – in the same state in the central U.S. Each site was purposively sampled to represent a different aspect of archaeological curation work today, including particular roles and activities that are central to the function of that institution (e.g., exhibition in the museum, and preservation in the repository). Site selection was informed in a broad sense by the researcher's archaeological and museum experiences. Access to the sites was arranged between the researcher, who was otherwise new to the site, and the professionals through personal communications. We used ethnographic methods of observation based on guiding questions, interviews, and follow-up conversation over two years, 2015 and 2016, as summarised in Table 1. The approach to data collection and analysis sought to clarify the functional priorities of the specific sector as well as disciplinary ways and practices of handling and manipulating data. Data collected in the form of photos, documentation (printed records), and detailed written notes and recordings were then synthesised and analysed qualitatively using the patterns outlined by Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw (1995, p. 150). Known commonly as open coding, the analytical technique in use here first identified many specific mini-activities (e.g., completing a record, quantifying sets of objects) described in the notes taken. From those many events, emerged four groupings of work activities (constructed categories). While we will not further examine excavation or conservation in this paper, we focus next on the two work activities of collections care and exhibition.

| State repository | State museum | |

|---|---|---|

| Professional roles interviewed | 7: Collections manager; Marine archaeologist; Head of records / Archaeologist; Site coordinator; Head of collections; Librarian; Archivist | 3: Registrar; Project director; Head conservator |

| Hours of observation and interview (date span) | 30 (Feb 2014-Oct 2015) | 35 (Apr 2015-Jan 2016) |

| Role in archaeological curation | Collections care; long-term storage procedures; environmental standards; condition reporting | Collection database; metadata capture; public display; storytelling |

| Constructed category | Collections care | Exhibition |

Subsequent to the two findings sections below, a synthesizing discussion will introduce the notion of a discontinuum to characterise archaeological curation work. While repository managers and museum curators (and others) all pursue common goals within the field of archaeology, the ways professional workers interact with artefacts and associated documentation are so singularly different, that the overall effect is a series of problematic data handoffs.

Findings

Repository managers

Repository managers carry out collections care through a unique focus on handling and storing various groups and formats of material in appropriate microclimates based on measurements of the artefacts' physical size. Each state in the U.S. implements the federal guidelines issued in 1990 as 36 Code of Federal Regulations Part 79, Curation of Federally-Owned and Administered Archeological Collections (Sullivan, 1992). An officially-designated archaeological institution or office within each state (Greengrass, 1999) maintains state-wide responsibility for documenting archaeological sites in that state, for issuing site numbers, for applying collection acquisition and management policies to reflect provenance, and for enforcing any state-specific curation guidelines, standards, or procedures. State repository managers work so that archaeological materials can be studied by people other than their original excavators. Repository managers may work, in archaeological repositories, alongside registrars and thus conduct collections care in an artefact context.

Repository managers closely read inventory forms that contract archaeologists submit with artefacts to the repository. The manager is most concerned with ensuring that there be enough information to allow the reuse of the material long-term – especially by future researchers. Yet we will see that the aspects of data that repository managers most value (measurements of physical size and extent) are not consistently those which other kinds of professionals value, though repository managers are not alone in their concern for provenance data. At the repository observed, a manager expressed how much more rapidly her work could proceed if only archaeologists had invested more time and effort into completing documentation in a certain way:

Think of the amount of time we would have saved at the end. People get very introspective and they can't see people having to do [different] jobs. They don't realize that if they did their job just 3% different, it would save me 97% of what I have to do. You taking five more minutes saves me 40 hours! (Repository manager, research observation 6 October 2015)

The repository manager is describing having received a few boxes of sorting bags in a submitted collection with artefacts mixed together from many different provenience lots from a project site (provenience is an archaeological term referring to the exact findspot of an artefact, an excavation location recordable in space and time). The bags were at odds with both the rest of the collection and with the inventory provided in the accompanying documentation, and had to be disassembled and the artefacts placed into the appropriate box. Such a task might have taken the original archaeologist minutes to do, but was ultimately left not done. This handoff problem could be easily resolvable in practical terms, but to be sustainable it would involve a conceptual shift across multiple professions, with each inspecting the data prior to handoff to ensure the artefacts match the given documentation.

Ultimately the repository manager's data preferences with regard to artefacts are very different from other professionals' preferences. We can explore these preferences by considering the data that managers gather to describe two levels of artefact access: collection-level and item-level metadata. At the collection level, managers record location data in the form of the originating geographic county (in the state) and also ascertain what materials were employed in the field to label collection materials (including ink, preservatives, water, acid bath, or dry brushing). Such collection-level data tell the archivist what environmental conditions the collection has encountered, and consequently how the collection needs to be managed in perpetuity. At the item level, managers record information about the historical periodization assigned to the site, the method of collection (i.e. kind of excavation survey), results of any prior inventory in the field or in the field lab, and finally a detailed listing of material classes and subclasses and the quantity of artefacts being submitted for permanent curation in each class. While the manager records the grand total number of items, it is total weight that is often both more practically useful and more meaningful, especially for bulk items in poorer condition. The appearance of the item and collection levels in an archaeological repository is depicted in Figure 2, where the items on the right side (project finds bagged according to their material class) are aggregated and then contained or placed in one of the collection boxes depicted on the left side. In sum, the manager places a high priority on being able to precisely quantify the collection, allocate and prepare space, and determine how to meet the environmental storage needs of the collection.

|  |

The repository manager fulfils an important stewardship role in the path of an archaeological artefact from its excavation in the dirt to its eventual presentation to the public via a museum exhibit. Managers create provenance research, in the course of inspecting and precisely quantifying objects, to supplement or supply information that may not have arrived as part of the accession materials. The provenance data that managers prepare today, often by liaising and maintaining extended communications with archaeologist-donors years after the original activity, is crucial to any eventual presentation of archaeological artefacts in an exhibit.

Long distance: museum curators' work

Broadly speaking, museums' primary role is to interpret historical events for the public. The museum presents a narrative using the objects on display, that has the effect of highlighting a certain angle, aspect of culture, or scholarly question. The context around which a museum presents a given historical narrative is at best artefact-informed; it is also parcel of the institution's broader politics and positioning – this applies especially to the work of curators in history museums. Museum curators usually work with many collaborators to prepare exhibits, including repository managers (to write the text and set artefacts in a narrative context) and conservators (to prepare selected artefacts or replicas for public display). In fact, by the time a museum curator interacts with an archaeological artefact for the purpose of planning its display in an exhibit, decades or centuries have often passed since that artefact was excavated, and even more time since it was created and used by people in society. For this reason, the museum curator conducts her work at a long distance, historically speaking, relative to the total trajectory that is contained within the artefact.

While exhibit displays remain a driver for museum work, large museums are increasingly engaged in efforts to expose provenance documentation for that large segment of the institutional collection holdings that is not publicly visible – see two such efforts by the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Archival Labels and MetObjects (Metropolitan, 2017; Roeder, 2017) as well as by the Museum of Modern Art (Roeder, 2015). Curators' work is incentivised differently than repository managers' work, and also there is a different set of public pressures on museums than on collection repositories. First, curators are concerned less with being able to precisely quantify each collection in their care than with ensuring those collections serve the mission and values of the museum as an educational institution and a place for public engagement with history. Curators act in fulfilment of the institutional mission and goals of the museum by applying scholarly expertise to the museum's holdings, both present and anticipated in future acquisitions. Book-length works analyzing curators' work are all-too-rare, notwithstanding Zuraleff (2006), but curators constantly balance the institution's internal collecting goals with the dynamics of existing within the heritage marketplace. Museum curators work within the physical structure of intended gallery spaces, negotiating artefact selection criteria and presentation manner within broader institutional and educational goals:

The next big challenge with the artefacts and databases in this project is populating this display case. Let's walk around: here they've finished installing the temporary new exhibit with our work area, there's the media display on the project's origins, and then there is a two-story display from the ground level, and we're identifying artefacts to go in there. The thought is that we'll have the glass bead box over the hull, and a ramp will come up for one to walk around this way to see other display cases. And up to about [10 feet] will be the large display case where we'll tell the story of why there are so many glass beads. Visually, the aim is to communicate very quickly the artefact classes and amounts that an explorer coming to the New World felt like they needed. Finally the superstructure will project outward in a dramatic final exhibit part. (Museum project director, research observation 24 July 2015)

Here the museum project director expresses the need to both identify exemplary objects among many hundreds or thousands available in the curated collection (e.g., the glass bead box) and employ spatial awareness in order to strategise an optimal gallery presentation. The museum interest in archaeological curation is revealed to be highly focused on the aesthetic and storytelling characteristics of particular objects in service of an overall narrative – not exhaustive quantification of the entire collection, but of representative choices and interpretation.

We must consider the path of both artefact and documentation, whether they are identical or separate, from the point of original excavation to the time of museum display. First, museum curators decide how to publicly present the provenance of objects that are selected for display, a decision that must acknowledge or address multiple individuals' contact with the collection over time. Examples of museums' decision-making in this regard include Rudolph's (2011) work exploring why a heritage collection should be kept together (rather than in separate institutions), and Jones's (2017) recent examination of museums' projects to provide access to their own field book archives. Second, curators receive the brunt of the public pressure to address the curation crisis in archaeology by making more artefacts accessible to more people. We note that provenance research for artefacts can have an immediate and significant impact on individual claimants and on the collective identity and memory of communities whose collective lives are presented in museum gallery spaces. Repatriation is one form of such impact, as are other outcomes which the labour of provenance research can make possible: exhibit catalogues, books, and object biographies. These latter outputs garner much less media attention than does a repatriation act, which may be accompanied by a public ceremony and presented as a success story of diplomacy (Flintoff, 2016). As one scholar writes, 'A simple statement that American-made films have been stored overseas, packed up, and shipped can be transformed into a publicity triumph by proclaiming the discovery of lost treasures to be ‘repatriated' and united with a grateful nation' (Frick, 2015, p. 116). But each outcome is made possible by museums' reliance on specific data and documentation being preserved long-term. Museums' collective interest in provenance research has grown over the past two decades, since high-profile repatriation cases have made the issue central, enveloping issues of shared identity and the power of and desire for community-driven intergenerational storytelling. Museum collections bear evidence of our fascination and preoccupation with objects, and how we use these objects to tell stories about our past and future as human beings. Museums will continue to play an important role in public sharing of archaeological materials, but as we have demonstrated there are problems encountered prior to exhibition that are impeding the immediate, and inclusive, legibility and interpretation of those materials.

Discussion: connecting the discontinuous assemblage

Each profession involved in the artefact path from excavation to exhibition uses specific data formats to document artefacts, creating new data that may borrow from parts of another's system. Above, we saw how repository managers record data about item size and composition, and museum curators compose displays to narrate how an artefact functioned during a historical period. Because these data are specific to one set of professional activities (preserving, or exhibiting), problems arise at the handoff points between such activities due to a lack of one consistent documentation system useful to all the professional communities. The handoffs of data between two communities collectively form a discontinuum of archaeological curation practice, as depicted in Figure 1.

An archaeological artefact can follow one of many possible paths from excavation to the site providing permanent retention: for example the artefact could traverse only two communities (from excavation straight to the museum), or three (excavation to conservation to repository) or all four. The artefact is also trailing with it a large bundle of documentation, which may follow that same path or another path entirely (and each community that encounters that documentation could do one of three activities: use, reformat, or discard prior data). There are many possible paths by which data are handed off from one community to another community, and the lack of continuity creates a curation discontinuum. Apart from the existence of multiple paths, the points of transition between professional groups, depicted as one-way arrows, are very problematic for both the artefact and the documentation. That is, consistently, one community transfers data to another, and the first community is not made aware of new changes or additions made at later stages of a project.

Museum curators draw on the databases and records created by excavator-archaeologists, conservators, and repository managers at earlier stages of archaeological projects, often occurring years or decades before an exhibit is planned. Museum curation work would be incomplete without those earlier contributions. For this reason, I reference the continuum concept from archival studies to express how each community's work builds cumulatively. The records continuum model as introduced by Australian archivists emphasises the continuing value of records (Upward, 1996 and 1997; Reed, 2013, p. 363; Lin, 2007, p. 107). The research revealed that while four communities coexist, they do not actively coordinate their efforts.

Mostern and Arksey (2016, p. 205) similarly argue that until a holistic view of 'the social life of data' becomes integrated in the originating profession's way of working, repository development and artefact description and access broadly will remain stagnated. More provocatively, Karimi and Rabbat's (2016) recent comments suggest that when we resort to telling public audiences about the afterlife of artefacts without physically showing them, we may obscure the true historical underpinnings of artefacts' destruction – whether by regime changes of one kind or another, ideological stance, or so-called modernist movements. Repository managers and curators need to better coordinate future practices to meet the dual challenges of the curation crisis and distributed data creation. While close observation allows me to articulate differences between them, overall the line between repository and museum institutions is thin (in a statewide public service division all functions can even happen under one roof). Additionally, we might recognise that coordination and cross-communication may be more feasible in the United States where graduate education for both archaeological repository-based and museum work, via a library or information science program, can sometimes be found in the same program or school. Archaeologists decades ago declared their own objects in crisis upon recognizing that public viewers cannot intuit the meaning of artefacts that are absent or missing from view, whether such absence is intentional or not.

Future work recommendations

Information workers across institutional settings must assist archaeologists in the effort to present and make accessible our archaeological heritage. Huvila's (2016) work demonstrates the benefits of pre-coordinating eight distinct information management activities performed in handling archaeological archives in Sweden, work that is being partially addressed in the international projects (e.g., Art Tracks and Ancient Itineraries) developing the Arches software and, in the U.S., the ArchaeoCore metadata schema (Newbury, 2016; Sanderson, 2018; Stylianopoulos, 2013). These projects, like much scientific work, are not apolitical, but rather are based on internalised disciplinary practices that become most visible during collaborative projects. Huvila notes that archaeological curation today reflects a complex history of distinct approaches; both the global nature of archaeological practice and the persistence of curation issues indicates that we must try out possible solutions.

The findings suggest that the repository and museum professions use specific processes to record particular data (elements) about artefacts. Ultimately the data a worker from each profession will produce are entirely unique from that of the other profession. Because the datasets are so specific to that set of professional activities, problems arise when one worker must hand off to another due to a lack of a consistent documentation system useful to all professions (i.e., the whole assemblage). The handoffs between the two professions collectively form a problematic discontinuum of practice. Most critically, the points of transition between professions create problems for both the artefact and its documentation. If the findings have shed light on reasons why the curation crisis persists, they have hopefully also located collaborative contact zones (Table 2). The Table summarizes two primary work interests for each of the repository and museum (columns 2 and 4), and shows how at least one from each directly overlaps with that of the other setting (row 3); a collaborative contact zone suggests ways to elevate existing contributions into purposeful collaboration. We must focus our information work on facilitating smoother data transitions at key points along the path of archaeological curation practice. Such work will ensure that provenance data captured at excavation fieldsites are not lost to all but the creator archaeologist who recorded it in her own handwriting.

| Interests of repository | Collaborative zone | Interests of museum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Collections care) | Physical sorting by material class and quantity | Identification of unusual visual characteristics | |

| (Collections care and exhibition) | Item- and collection-level condition reporting | Creation and use of very descriptive metadata | Writing an engaging narrative |

| (Exhibition) | Liaising with all project members | Integrating object data from long distance |

Managers' and museum curators' work as we view it today will increasingly overlap with that of public archaeologists – and occur outside of museum institutions – as our built, immovable heritage comes to demand critical attention, suggests Emerick (Wells, 2017, p. 778). We are compelled to continue the important work that scholars have pioneered in the area of archaeological curation and extend it so that data are shared responsively and engagingly with the public. It is important that we continue to survey archaeological repositories and follow the collections even as organizational placements and institutional structures change between universities, museums, and other non-profit or government-based entities.

Conclusion: assembling professional collaboration

Curation is not limited to museum-based work, but is best understood as distributed work occupying multiple sites and professions. Data practices and the technologies used to record data (and create scholarship) are not uniform, but a provident focus on connecting these data to specific activities with which the public can engage will improve collections' long-term impact. In conclusion, archaeological collections are a challenging kind of material to organise. Information researchers are creating museum-specific teaching materials so that student curators can expand their descriptive and storytelling skillsets and gain readiness to manage heritage collections (Krmpotich, 2015, p. 115). We might glean further motivation from an oft-repeated principle that has circulated in the archival field for a decade but now might have a renewed urgency (and poignancy): 'more product less process' (Greene and Meissner, 2005). Archivists have elevated Greene and Meissner's advice to the status of best practice because it reminds archivists to keep product, or visible results, at the forefront of daily efforts. As museums face growing demands for delivering artefact data both to establish provenance (authenticity) and answer centuries-old claims on historic property, we should create learning connections across the information and archaeological professions.

The study considered the problem of archaeological curation by examining what work activities repository and museum professionals choose to perform on collections. Ethnographic methods of data collection and analysis revealed that discontinuous data interaction activities are being performed by the two professions; while suggesting that distinct roles will continue to persist, this discovery more significantly reveals collaborative contact zones with rich opportunities for information researchers. Such collaborative zones include: (1) identification of unusual visual characteristics, (2) creation and use of very descriptive metadata, and (3) liaising with all project members. Perhaps the most persistent obstacle to the future development of archaeological curation domain is not space for collections, but sufficient human and financial resources to meet subsequent need. In arguing for why the solutions forward will necessarily be interdisciplinary, opportunities have been illustrated for information researchers to pursue further collaborative efforts. Information workers in repositories and museums can work in parallel to advance public access to cultural heritage.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Beta Phi Mu for supporting this research with a dissertation fellowship, and to Professor Patricia Galloway, my dissertation advisor.

About the author

Sarah A. Buchanan is Assistant Professor in the iSchool at University of Missouri, where she teaches in the archival studies area. She received her Ph.D. from The University of Texas at Austin. She can be contacted at buchanans@missouri.edu

References

- Allen, L., Stewart, C. & Wright, S. (2017). Strategic open data preservation: Roles and opportunities for broader engagement by librarians and the public. College & Research Libraries News, 78(9), 482-485. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.5860/crln.78.9.482 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qCrIzB7)

- Altschul, J.H. (2016). The role of synthesis in American archaeology and Cultural Resource Management as seen through an Arizona lens. Journal of Arizona Archaeology, 4(1), 68–81.

- Banks, K.M., Lee, C. & Engel, D. (2016). Where the buffalo roam: The National Historic Preservation Act and the Northern Plains. In K.M. Banks & A.M. Scott (Eds.) The National Historic Preservation Act: Past, Present, and Future (pp. 163–180). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Barker, A.W. (2010). Exhibiting archaeology: archaeology and museums. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 293-308.

- Bates, J., Goodale, P. & Lin, Y.-W. (2015). Data journeys as an approach for exploring the socio-cultural shaping of (big) data. The case of climate science in the United Kingdom. In iConference 2015 Preliminary Results Papers. Urbana-Champagne, IL: University of Illinois. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2142/73429 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qD8PgLH)

- Berlin, J. (2015, May 14). How Indiana Jones actually changed archaeology: Blockbuster film series led to spike in archaeology courses, careers. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150514-indiana-jones-archaeology-exhibit-national-geographic-museum/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qDGRqFU)

- Brodie, N. (2011). Congenial bedfellows? The academy and the antiquities trade. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 27(4), 408-437.

- Bullard, G. (2014, May 19). Government doubles official estimate: there are 35,000 active museums in the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services. Retrieved from https://www.imls.gov/news-events/news-releases/government-doubles-official-estimate-there-are-35000-active-museums-us (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qDY4xsj)

- Childs, T. (1995). The curation crisis. Federal archeology 7(4), 11-15. Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/archeology/cg/fd_vol7_num4/crisis.htm (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qDrWKjZ)

- Childs, S.T. (2004). Our collective responsibility: the ethics and practice of archaeological collections stewardship. Washington, D.C.: Society for American Archaeology Press.

- Childs, S.T. (2010, Fall). The dollars and sense of managing archaeological collections. Heritage Management 3(2), 155-166.

- Childs, S.T. & Kagan, S. (2008). A decade of study into repository fees for archeological curation. Washington, DC: National Park Service. (U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers, 98). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/98 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qE0EKmF)

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I. & Shaw, L. L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Fagette, P. (1996). Digging for dollars: American archaeology and the New Deal. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

- Flintoff, C. (2016, Mar. 5). U.S. returns historical documents, stolen from Russia in chaotic '90s. NPR Morning Edition. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2016/03/05/469202458/u-s-returns-historical-documents-stolen-from-russia-in-chaotic-90s (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qED8nmN)

- Frick, C. (2015, Feb.). Repatriating American film heritage or heritage hoarding? Digital opportunities for traditional film archive policy. Convergence: The international journal of research into new media technologies 21(1), 116-131.

- Greene, M. & Meissner, D. (2005). More product, less process: revamping traditional archival processing. The American Archivist, 68(2), 208-263.

- Greengrass, M. (1999). State archeology weeks: Interpreting archeology for the public. Technical Brief 15. Washington, DC: National Park Service, Archaeology Program. Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/archeology/pubs/techbr/tchbrf15.htm (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qEJcL5L)

- Heyman, I.M. (1997). Perspectives: using and taking care of 140 million items. Smithsonian 28(5), 10-17.

- Historic England. (2018). New plan to address England's archaeology archives challenge. Historic England. Retrieved from https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/news/new-plan-englands-archaeology-archives-challenge (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qEVYUF7)

- Hitchcock, A. (1994). Archeological and natural resource collections of the National Park Service: opportunities and threats. Curator: The Museum Journal 37(2): 122-128.

- Holovachov, O., Zatushevsky, A. & Shydlovsky, I. (2014). Whole-drawer imaging of entomological collections. Benefits, limitations and alternative applications. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 12(1) article 9: 1-13. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021218 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qEcv12h)

- Huvila, I. (2016). If we just knew who should do it, or the social organization of the archiving of archaeology in Sweden. Information Research, 21(2), paper 713. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/21-2/paper713.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qEntLhS

- Iliadis, A. & Russo, F. (2016). Critical data studies: an introduction. Big Data & Society 3(2), 1-7. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716674238 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qEumM54

- Jelks, E.B. (1989). Curation of federal archaeological collections of the Southwest Division, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Normal, IL: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Southwestern Division.

- Johnston, L. (2014, March, 25). What could curation possibly mean? [Web log post.] The signal: digital preservation. Retrieved from https://blogs.loc.gov/thesignal/2014/03/what-could-curation-possibly-mean/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qF1VTJe)

- Jones, M. (2017). From personal to public: field books, museums, and the opening of the archives. Archives and Records, 38(2), 1-16.

- Karimi, P. & Rabbat, N. (2016, December 12). The demise and afterlife of artifacts. Aggregate. Retrieved from http://we-aggregate.org/piece/the-demise-and-afterlife-of-artifacts (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qFYblXH)

- Kersel, M.M. (2015a). Storage wars: Solving the archaeological curation crisis? Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies, 3(1), 42-54.

- Kersel, M.M. (2015b). An issue of ethics? Curation and the obligations of archaeology. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies, 3(1), 77-80.

- Kirakosian, K. & Bauer-Clapp, H. (2017). A walk in the woods: Adapting archaeological training to archival discovery. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 5(3), 297-304. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2017.17 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qFjYoCa)

- Krmpotich, C. (2015). Teaching collections management anthropologically. Museum anthropology, 38(2), 112-122.

- Lee, C.A. & Tibbo, H. (2011, Fall). Where's the archivist in digital curation? Exploring the possibilities through a matrix of knowledge and skills. Archivaria, The journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists, (No. 72), 123-168. Retrieved from http://journals.sfu.ca/archivar/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13362 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qHKsuYP)

- Lin, C-S. (2007). Records continuum: an emerging recordkeeping theory. Journal of library and information studies, 5(1/2), 107-137. Retrieved from http://eprints.rclis.org/14559/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qHW0wXF)

- Lubar, S., Rieppel, L., Daly, A. & Duffy, K. (2017). Introduction: lost museums. Museum History Journal, 10(1), 1-14. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.1080/19369816.2016.1259330 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qHc5L0c)

- Lucas, G. (2012). Understanding the archaeological record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Marquardt, W.H., Montet-White, A. & Scholtz, S.C. (1982). Resolving the crisis in archaeological collections curation. American Antiquity, 47(2), 409-418.

- Marty, P.F. (2009). An introduction to digital convergence: libraries, archives, and museums in the information age. Museum Management and Curatorship, 24(4), 295-298.

- Merriman, N. & Swain, H. (1999, Aug.). Archaeological archives: serving the public interest? European Journal of Archaeology, 2(2), 249-267.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. (2017). Archival labels. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://www.metmuseum.org/art/libraries-and-research-centers/leonard-lauder-research-center/cubist-collection/archival-labels (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qHkvctW)

- Milanich, J.T. (2005). Letter from Arizona: homeless collections. Archaeology, 58(6). Retrieved from http://archive.archaeology.org/0511/abstracts/letter.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qHoe10r)

- Mostern, R. & Arksey, M. (2016). Don't just build it, they probably won't come: data sharing and the social life of data in the historical quantitative social sciences. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 10(2), 205-224.

- Nelson, M.C. & Shears, B. (1996). From the field to the files: curation and the future of academic archaeology. Common Ground, 1(2), 34-37. Retrieved from https://home.nps.gov/archeology/cg/vol1_num2/files.htm (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qHwFOPY)

- Newbury, D. (2016). Art tracks: a technical deep dive. Paper presented at Art Tracks: 2016 Digital Provenance Symposium. [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.museumprovenance.org/pages/scholars_day_2016/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qI8CNLf) [Editor's note: very poor sound quality]

- Nichols, C.A. & Lowman, C.B. (2018). A common thread: recognizing the contributions of the Summer Institute in Museum Anthropology to graduate training with anthropological museum collections. Museum Anthropology, 41(1), 5–12. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/muan.12165 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qIF1UNw)

- Orcutt, K. (2011). The open storage dilemma. Journal of Museum Education, (Protecting the objects and serving the public special issue) 36(2), 209-216.

- Panella, C. (2015). Lost in translation: ‘unprovenanced objects' and the opacity/transparency agenda of museums' policies. Anuac: Rivista della Società Italiana di Antropologia Culturale, 4(1), 66-87. Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.7340/ANUAC2239-625X-1874 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qIZzi33)

- Pearce, S.M. (1990). Archaeological curatorship. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Perrin, K.K. (2009). A future for the past: the work of the Archaeological Archives Forum in the UK and the EAC Archives Working Party in Europe. SAA Archaeological Record, 9(2), 9-12. Retrieved from https://documents.saa.org/container/docs/default-source/doc-publications/publications/the-saa-archaeological-record/tsar-2009/mar09.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qJSUkh2)

- Phelan, M.E. (1993). A synopsis of the laws protecting our cultural heritage. New England Law Review, 28, 63-108. Retrieved from https://ttu-ir.tdl.org/handle/10601/63 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qJjXIhf)

- Reed, V. (2013). Due diligence, provenance research, and the acquisition process at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law, 23(2), 363-373. Retrieved from https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol23/iss2/4/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qJrX9sH)

- Renascence. (2018). In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/renascence (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qIKpahh)

- Roeder, O. (2015, Aug. 28). A nerd's guide to the 2,229 paintings at MoMA. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/a-nerds-guide-to-the-2229-paintings-at-moma/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qJvyuKd)

- Roeder, O. (2017, April 6). An excavation of one of the world's greatest art collections. FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved from http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/an-excavation-of-one-of-the-worlds-greatest-art-collections/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qK1sWHO)

- Rudolph, K. (2011). Separated at appraisal: maintaining the archival bond between archives collections and museum objects. Archival issues, 33(1), 25-39. Retrieved from http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/72333 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qK8A4Mz)

- Sanderson, R. (2018, August 18). Computing the provenance of art. [Web log post]. Ancient Itineraries. Retrieved from https://ancientitineraries.org/2018/08/18/computing-the-provenance-of-art/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKDjjlY)

- Singh, K. & Brusius, M. (Eds). (2018). Museum storage and meaning: tales from the crypt. London: Routledge.

- Srnicek, N. (2007). Assemblage theory, complexity and contentious politics: the political ontology of Gilles Deleuze. Unpublished Master's thesis, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.urbanlab.org/articles/AssemblageTheoryComplexityandContent.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKIEngb)

- Stylianopoulos, L. (2013). Managing the digital dig: partnerships and progress on the ArchaeoCore Metadata Project. Paper presented at Archaeology Archives: Excavating the Record, Visual Resources Association 31st Annual Conference, 4 April, Providence, RI. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/gsas/dept/fineart/pdfs/archaeology/Stylianopoulos.Paper.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/77Kwg5kzD)

- Sullivan, L.P. (1992). Managing archeological resources from the museum perspective. . Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, Archaeology Program. (Technical Brief 13). Retrieved from http://www.nps.gov/archeology/PUBS/TECHBR/tch13A.htm (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKi7z1f)

- Sullivan, L.P. & Childs, S.T. (2003). Curating archaeological collections: from the field to the repository. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press. (Archaeologist's toolkit: Vol. 6)

- Swain, H. (2007). An introduction to museum archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thurlow, B. (2011, April 12). Indiana Jones invades Montreal. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/blog/collection/indiana-jones-invades-montreal/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKmddSb)

- Thurlow, B. (2011, April 18). Indiana Jones and the Penn Museum. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/blog/collection/indiana-jones-and-the-penn-museum/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKqXxRa)

- Thurlow, B. (2011, April 19). Raiders of the Lost Ark vs. Sitio Conte. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/blog/museum/raiders-of-the-lost-ark-vs-sitio-conte/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKucnli)

- Thurlow, B. (2011, April 21). Culture clash and the Temple of Doom. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/blog/collection/culture-clash-and-the-temple-of-doom/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qKy6orG)

- Thurlow, B. (2011, April 21). Every object tells a story. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/blog/collection/every-object-tells-a-story/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qL3lkcq)

- Thurlow, B. (2011, April 25). Nazca vs. aliens. [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://www.penn.museum/blog/collection/nazca-vs-aliens/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qL7Tfc5).

- Upward, F. (1996). Structuring the records continuum - Part one: Postcustodial principles and properties. Archives and Manuscripts, 24(2), 268-285.

- Upward, F. (1997). Structuring the records continuum - Part two: Structuration theory and recordkeeping. Archives and Manuscripts, 25(1), 10–35.

- Voss, B.L. (2012). Curation as research. A case study in orphaned and underreported archaeological collections. Archaeological dialogues, 19(2), 145-169.

- Wagley, C. (2014, Feb. 7). Today's Monuments Men are on the internet. LA Weekly. Retrieved from http://www.laweekly.com/content/printView/4413455 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75qLGmfRu)

- Watts, J. (2011). Policies, preservation, and access to digital resources: the Digital Antiquity 2010 National Repositories Survey. Digital Antiquity. (Reports in Digital Archaeology 2). Retrieved from https://www.digitalantiquity.org/wp-uploads/2011/07/20111215_Final.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/77Ky9QB90)

- Wells, J.C. (2017). Review of Conserving and managing ancient monuments: heritage, democracy, and inclusion, by Keith Emerick. International Journal of Heritage Studies 23(8), 778-780.

- Wingfield, C. (2017). Collection as (re)assemblage: refreshing museum archaeology. World Archaeology, 49(5), 594–607.

- Zuravleff, M.K. (2006). The bowl is already broken: a novel. New York, NY: Picador.