Information science and North American archaeology: examining the potential for collaboration

Justin P. Williams and Rachel D. Williams

Introduction. To understand how archaeologists produce and manage project data, we conducted a pilot survey of North American archaeologists.

Method. We conducted a pilot survey using Qualtrics online survey service. The questionnaire contained fourteen questions related to project data management challenges and perspectives, along with questions regarding the potential for collaboration between archaeologists and information professionals. Additionally, we review a small vignette of archaeological research.

Analysis. We used descriptive statistics and a thematic analysis of open-ended questions to identify important trends and topics related to our two research questions.

Results. Our survey found that archaeologists perceive storing project data and making project data available outside their organization to be the most challenging parts of their work. We also found that most archaeologists are interested in collaborating with information professionals.

Conclusion. This study identified the challenges archaeologists encounter in data management and potential for collaboration between archaeologists and information professionals in terms of research data management and sustainability and usability of research data.

Introduction

At the core of archaeology is understanding of the context of the past through the information that a place's inhabitants left behind in the form of artefacts. In North America, archaeologists work for a variety of organizations and therefore have varying information management goals. Some archaeologists may spend the majority of their time out in the field conducting survey and fieldwork, while others teach and do research. Still others manage a variety of projects and review the reports written by others. Regardless of their position, it is at the crossroads of artefacts, information, and context that archaeological practice exists. As Bates (1999) points out, information science cuts across traditional disciplines such as archaeology. In that nexus of archaeological practice is also potentially an information scientist. Inherent at that crossroads, then, is the need to examine the information management practices of archaeologists as they conduct field projects and process archaeological data for storage, curation, and dissemination. As Huvila and Huggett state:

Much has been written about archaeological practices but a critical understanding of the practices of knowledge production in and about archaeology, based on explicit and openly problematizing interrogative reflection, remains fragmented (Huvila and Huggett, 2018, p. 88).

Our study is focused on exploring how archaeologists perceive their work practices and their processes in managing project data and asks archaeologists to share their perspectives on the potential work that information professionals may be able to provide when it comes to managing workflows and data. Our research questions are as follows:

What challenges do archaeologists experience in the collection, curation, and management of project data?

What potential role(s) do information professionals have in easing the challenges associated with archaeologists' project data management work?

Drawing on the results of a pilot survey and an archaeological case exemplifying the challenges of project data management in archaeology, this paper seeks to better understand the role of information management in archaeological practice. Many studies within library and information science have explored the role of information in scientific professions (for example, Ellis and Haugan, 1997). Much of previous research on archaeology within the field of information science has focused on the use of metadata to curate archaeological collections, their field methodologies, their information source use, and interpersonal interactions between archaeologists and various other parties with an interest in the past (Beaudoin and Brady, 2011; Huvila, 2014; Olsson, 2016). Some studies have focused on the potential for archaeologists to adopt digital technology in the field the better to record the context of artefacts during archaeological excavation (Ellis, 2016).

Additional studies have focused on the archaeological practice in a digital world. Some work analyses the data lifecycle to examine issues with archaeological information management, while others have focused on the development of hardware and software tools (See for example, Ross, Sobotkova, Ballsun-Stanton and Crook, 2013; Uildriks, 2016). Others have critiqued the move of archaeology into the digital age (Caraher 2015). Some projects have recently been undertaken to develop repositories to ensure that data can be stored, accessed, and used, such as the Digital Archaeological Repository in the United States and the Archaeological Data Service in the United Kingdom (McManamon, Kintigh, Ellison and Brin, 2017). However, as McManamon and colleagues argue, it is important to note that infrastructure is not enough: it is vital to understand and revise archaeological practices to address the digital landscape in which archaeologists are now working. Kansa, Kansa, and Arbuckle (2014) explain that the importance of data archiving and reuse have increased recently within archaeology, which presents opportunities to examine data workflows to facilitate the transformation of raw data into reusable data. As Faniel, Kansa, Whitcher Kansa, Barrera-Gomez, and Yakel (2013) note, the challenges of archaeological data management are further complicated by the very nature of archaeological practice, in which context (or a lack of it) can pose issues with the reuse of data.

Archaeologists have long adopted field and laboratory methods for finding and preserving artefacts of the past. They are, arguably, experts at data creation, curation, and reproduction. While information scientists have studied these methods to some extent, they have an opportunity to examine archaeological practices and challenges with a view toward addressing project data management needs. We see the potential for collaboration between information scientists and archaeologists, particularly when it comes to understanding how archaeologists describe and manage data. Although limited, previous work in the information field that focuses on archaeologists has examined the use of metadata as a tool for archaeological collections as well as their information behaviour and interactions among themselves and between various other groups (Huvila, 2011; 2014; Kulasekaran, Trelogan, Esteva, and Johnson, 2014). Huvila's (2011) study explored how archaeological reports act as boundary objects between different groups of interested parties. This study points to issues of power and legitimization among the various parties involved in the report. Olsson (2016) explored the information cultures of archaeologists with a focus on the embodied nature of their information practice. Our paper is focused on orienting the challenges faced by archaeologists in collecting and managing project data in order to identify potential areas of collaboration with information professionals.

In an effort to understand better the production of archaeological information and, furthermore, give North American archaeologists a voice in how information scientists may help them in this pursuit, we conducted a pilot survey of North American archaeologists working in a variety of professional settings.

Digital analysis of Clovis and other Paleo-indian artefacts

To build on the results of this study, we begin with a small vignette, which details some of the challenges faced by archaeologists when finding and using archaeological data. Bearing this example in mind while considering the responses from participants to the pilot survey, helps highlight how difficult and complex project data management can be for an archaeologist. In this example, while this research was conducted within the academic sphere of archaeology, data from private, government, and tribal run projects were also used.

One of the more popular subjects in North American archaeology is seeking the origin and method of spread of an ancient spear point known as the Clovis point. The example of Paleo-indian spear points highlights many of the difficulties of data management, storage, and acquisition that were identified by the surveyed archaeologists. This vignette will also show how information scientists can learn from the practices of archaeologists who adopt novel approaches to data collection and management.

The study of morphological variability of Clovis spear points includes the specific dataset of points, which are thought to have been made between 13,110 and 12,660 calendar years ago even though some are found in sites outside the scope of these dates (Waters and Stafford 2007; Sanchez et al., 2014). The people who made and used these spear points are known to be one of the earliest cultures in North America. This spear-point technology was wide spread across North America, though it is now widely agreed that there were several cultures that existed in the new world before Clovis (Bradley, Collins, Hemmings, Shoberg, and Lohse, 2010; Buchanan and Collard, 2007; Meltzer, 2004; Williams, 2016). These spear points are often found in association with extinct megafauna such as mammoths and mastodons (Haynes, 2002; Williams, 2016). For an example of an archaeological data set of Clovis hafted biface measurements see Appendix A in Williams (2016).

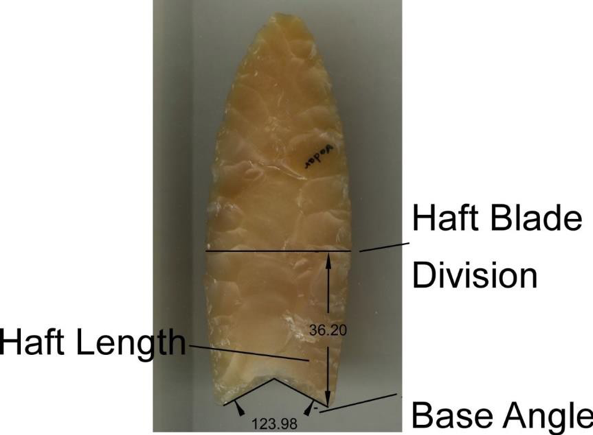

Compared to other archaeological cultures, Clovis is, geographically, very well spread across North America. Clovis points are found throughout the United States and in Northern Mexico (Bradley, et al., 2010; Buchanan and Collard, 2007; Morrow and Morrow, 1999; Sanchez et al., 2014; Williams, 2016). Thus, Clovis points are held by numerous museums and other institutions which are also, understandably, widely spread across the United States and Mexico. It can therefore be very expensive and time consuming for a researcher to visit these institutions to conduct research. Additionally, Clovis points are very aesthetically pleasing and are, unfortunately, prized by non-archaeologists such as collectors (See Figure 1). Clovis points, which are already rare, are increasingly difficult for archaeologists to access for research purposes, in part due to their frequency in non-curated private collections.

What makes locating and researching them even more difficult is the fact that Clovis points that are found 'in good context' (meaning excavated carefully by archaeologists) are exceedingly rare. In archaeology, context is the most important aspect of the information about an artefact. Many artefacts can only be accurately dated due to their proximity or association with another feature within a soil profile or another artefact. Therefore, the rarity of accurately excavated Clovis points makes efforts to study them difficult and complex.

To address these challenges, many archaeologists have moved away from analysing actual Clovis spear points and switched to the analysis of digital images of them (see Bradley, et al., 2010; Buchanan and Collard, 2007; Williams, 2016 for a few examples). However, finding funds, building databases and repositories for digital images, and acquiring these digital images has been a significant challenge for archaeologists. For this project, Williams (2016) took images of over 700 artefacts and several measurements on each of those images. As a result, the dataset includes thousands of measurements and images that are not currently accessible to anyone except the researcher. Storing the numerical data associated with artefacts is often feasible. However, storing the image data and sharing these images of points with others is often incredibly challenging (see Figure 1 for an example of the high quality images that can be used for analysis).

What are the best options for storing large amounts of archaeological project data? Currently, to address data accessibility and interoperability issues, some archaeologists have collaborated to create repositories for artefacts (of which Clovis is one type). Examples include the Paleo-indian Database of the Americas (PIDBA) and the Digital Index of North American Archaeology (DINAA) (Anderson et al., 2010; Anderson et al., 2017; Kansa et al., 2018; Yerka et al., 2012; Yerka et al., 2015). The PIDBA curates information about the location and morphology of Clovis and other fluted points for the Paleo-indian Period and serves as a repository for digital images and line drawings of them. The DINA is not as limited in scope and includes artefacts from all time periods and geographic locations across North America (Anderson et al., 2017). Although enjoying some success, these efforts are done on a minimal budget and therefore with limited scope. Williams (2016) utilized images during his analysis, while Prasciunas (2011) utilized geographical data to discuss fluted points. Despite these early forays into open-source data reuse, many archaeologists still rely on traditional methods of data acquisition. These activities might involve consulting large books and field reports with appendices filled with data, and, as with many other disciplines, reaching out to peers (Faniel and Yakel, 2017). The PIDBA and DINA are wonderful examples of archaeological online data repositories, but they could be improved via collaboration to develop specialized metadata for not only images but their contexts and spatial measurements as well.

Beyond simply storing large amounts of data, such as those illustrated by this example, is the problem of making those data accessible to other researchers and the public over the long-term. Often, archaeological collections are project and/or organization specific, and finding ways to connect those organizations and actors together is difficult, as is overcoming governmental and logistical hurdles that inhibit forging those connections. . Archaeologists rely on their own expertise and that of their colleagues to find information and solve problems. Maps, books, and reports are also often useful tools for understanding an issue more fully.

Here we have outlined a few of the project and data management challenges faced by archaeologists who study Paleo-indian spear-point technology. Though it is not a subject matter relevant to all North American archaeologists, this exemplifies the three major challenges identified by the archaeologists surveyed in this study: collecting data, data storage, and sharing data with interested parties outside one's organization. Data storage is a challenge in the case of the Clovis example because Paleo-indian points are curated at various museums throughout North America. This makes study difficult, as archaeologists have to travel to many locations or find ways of accessing digitized images of artefacts and, in some cases, creating those images if they do not already exist. Further, some of these points are simply tagged as points and not Paleo-indian points, making them difficult to locate even for professionals. Sharing these data is risky, because the public highly values Paleo-indian points, and the open sharing of locational data could lead to looting. Because many Paleo-indian points are owned by private citizens, collecting additional data on these points is difficult. Thus they are rare, and, as previously mentioned, are curated at institutions throughout North America. Institutions have various standards and internal practices that can make accessing, digitizing, and using these collections challenging. Through the aid of information professionals, archaeologists would be able to face the challenges, specifically within the study of Paleo-indian spear points and more generally across many archaeological subjects and collections.

Methods

The study includes a series of questions in an open-ended format that was developed using Qualtrics. The questionnaire included a variety of questions centred on work experience and interest in collaboration with information professionals (See Appendix A for a complete list of questions). Participants were recruited voluntarily. We used a convenience sample and snowballing technique, allowing participants to share the link to the survey widely with colleagues both inside and outside their organization. Our recruitment was centred on North American archaeologists. Invitations for participation were sent to academic, corporate, and governmental institutions as well as one professional organization by e-mail. Respondents were encouraged to participate with a random drawing for US$25 gift cards.

In total we had 53 total respondents, 24 of whom completed all the questions on the survey. A total of 35 respondents answered the majority of the survey questions (more than 10 of the 18 questions). The respondents are affiliated with a variety of archaeological institutions, including private sector cultural resource management firms, universities, tribal archaeological agencies, museum and curation facilities, and government. Of the 24 respondents who completed the survey, 14 (58%) worked in the private sector, 5 (21%) worked for a government agency, 3 (13%) were from colleges or universities, 1 worked at a museum (4%), and 1 at a tribal archaeological agency (4%). While the sample size is small, we feel that this distribution of archaeologists represents a good range of North American archaeological institutions. The participants had wide-ranging archaeological experience, with 2 to 44 years within the field. All respondents live and work in North America. We recognize that archaeology in North America and Europe operates under widely different laws, requirements, and professional cultures. This sample represents the archaeologists working in North America but is not representative of archaeologists operating in other regions.

Given the fact that this is a pilot study, our analysis necessarily prioritized descriptive statistics, specifically numerical counts and percentages of responses for categories. We also conducted a thematic analysis of the responses to open-ended question in order to identify additional themes related to the two research questions.

Results

The primary focus of this survey was twofold. First, we sought to evaluate the challenges faced by archaeologists concerning data management. Secondly, we examined the experience and willingness of archaeologists to work with information professionals. The questions first focused on what may be considered traditional archaeological practice and information work related to such practice, following with open-ended questions that gave respondents an opportunity to expand on ways in which they might see information scientists collaborating with archaeologists. We chose to address traditional aspects of information practice first because, as outlined earlier, archaeologists tend to fall back on traditional modes of seeking information and help with data-related questions. These might involve asking a colleague, looking for information in a book, or looking at maps and images to better understand aspects of a project location and context.

To evaluate the challenges faced by archaeologists in the process of acquiring and managing project data, we asked a series of five questions. The results of this portion of the survey are presented in Table 1. A few trends are apparent from these data. More than half of all archaeologists surveyed find describing and indexing data, storing data, and making project data accessible to co-workers not at all challenging. Additionally, approximately 20 percent of those surveyed find storing archaeological data very challenging. This suggested that there is little agreement among archaeologists regarding the difficulty of data storage. Only 16 percent of archaeologists surveyed find the sharing of data with professionals outside their organization to be not to be challenging at all, which leads to the conclusion that this aspect of archaeological data is challenging for the majority of archaeologists. Unsurprisingly, collecting project data was found to be at least a little challenging by 54% of the archaeologists surveyed although only one archaeologist (4 percent) found it to be very challenging. Overall, these data indicate that collecting project data, data storage, and sharing data with professionals outside their organization to be the most challenging data-related aspect of their positions.

| Challenges of archaeological data management | Not at all challenging | A little bit challenging | Somewhat challenging | Very challenging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collecting project data | 12 (46%) | 8 (31%) | 5 (19%) | 1 (4%) |

| Describing/indexing project data | 14 (54%) | 9 (35%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) |

| Storing project data | 16 (62%) | 4 (15%) | 1 (4%) | 5 (19%) |

| Making project data accessible to co-workers inside my organization | 17 (65%) | 6 (23%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

| Making project data accessible to professionals outside my organization | 4 (16%) | 10 (40%) | 8 (32%) | 3 (12%) |

Beyond evaluating the challenges archaeologists experienced in project data management, the survey also addressed the potential for collaboration between archaeologists and information professionals. We collected data about archaeologists' previous experience with information professionals and their willingness to work with them in the future. A total of nine archaeologists indicated that they had worked with an information professional. All of those who had worked with information professionals explained that they worked with archaeologists in either data management roles or as staff to assist in searching for information.

In terms of working with information professionals to manage project data, participants had mixed views on the utility of collaboration (Table 2).

| Previous experience working with an information rofessional or librarian in an archaeological setting | Archaeologists |

|---|---|

| No experience working with information professionals or librarians | 14 (58%) |

| A librarian helped manage project data for my organization | 3 (13%) |

| A librarian helped manage books and other materials for my organization | 2 (8%) |

| A librarian searched for information for me | 3 (13%) |

| A librarian was/is on staff in my organization | 3 (13%) |

| Other form of information professional help | 3 (13%) |

A third of respondents, 8 of 24, shared that they had experience collaborating with an information professional before taking the survey. All of those who had worked with information professionals previously described interest in collaborating. Out of the 24 completed surveys, a total of 13 (54%) indicated that they would probably or definitely be interested in collaborating with information professionals (Table 3). Of the survey responses, 9 (37%) shared that they might or might not be interested in collaborating with information professionals. It should also be noted that all of those who would definitely not or probably not be interested in collaborating with information professionals were situated in organizations in the private sphere. This may be due to the profit-oriented nature of these projects and the tendency of the private sphere to work on projects where locational data, of both archaeological sites and the bounds of the project area itself, may have to be kept confidential. Keeping the project boundaries unknown can be particularly important on natural resource evaluation projects (such as mining and oil extraction locations), which is nearly exclusively conducted by archaeologists in the private sphere. Almost all of those who completed surveys had at least some interest in collaboration, with a focus on several key areas. These needs centred on: identifying best practices; data integrity and sustainability; efficiency; and managing large amounts of data effectively.

| Interest in collaborating with information professionals to manage project data | Total archaeologists | Government | Private project | Tribe | Museum | Academic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definitely not | 1 (4%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Probably not | 2 (8%) | 0 | 2 (8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Might or might not | 8 (33%) | 0 | 6 (25%) | 0 | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) |

| Probably yes | 5 (21%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Definitely yes | 8 (33%) | 2( 8%) | 4(16%) | 1 (4%) | 0 | 2 (8%) |

| Total | 24 (100%) | 5 (21%) | 14 (59%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (12%) |

According to participants, identifying best practices for handling project data involved exploring innovative ways to manage data, how to construct metadata that is more descriptive, and organizing and disseminating data effectively to a variety of other parties. Expressing frustration with data management, one participant explained,

Archaeologists tend to be unfortunately disorganized and scattered, even though our discipline deals with a great deal of complex data. Hiring data management professionals is a necessary cost at this point given the volume of lost information as a result of poor practices. This is not appropriate to treatment information in this way in science, for tribes, or for compliance.

Another archaeologist attributed what they termed 'data mismanagement' to staff attrition and turnover, which occurs most often during the summer field season, when organizations hire extra staff to assist with projects.

When describing data integrity and sustainability, archaeologists explained that it was important to manage both current and legacy versions of data, particularly when it came to collaborating with other staff members. Ensuring that the right version of the right document was accessible and usable at all times was important. They also described information professionals as mediators, who can organize and disseminate files correctly and share that information with a variety of interested parties. One participant noted the challenges in working with the information professional on staff, an archivist, explaining that,

They are not archaeologically trained and there were sometimes issues with their understanding of the types of data we collect, how we share it, how active the information is (for both researchers and updates to artefact identifications or comments).

This archaeologist further described issues with availability of the archivist, namely that 'they generally do not work within our organization, directly, so their assistance and expertise is not always readily available.'

Sustainability was described in terms of long-term storage of data in usable formats as well as prioritizing files and organizing them with the future in mind. As one archaeologist put it, it is important for 'creating reference files that endure time and similar/repeat projects.' Efficiency and managing large amounts of data were also important areas of concern for archaeologists. Efficiency was described in terms of storing the data, time, finding obscure data more easily, and organization designed for better workflow. Managing large and complex data sets was viewed as an important area in which having an information professional available to assist with identifying the best ways to manage these collections was very helpful. Some recent work has begun undertaking these issues, for instance the Federated Archaeological Information Management Systems (FAIMS) project. According to the authors, this project examines the archaeological data lifecycle 'for opportunities to improve efficiency and enhance the quality of data' (Ross, et al., 2013). Long-term, the FAIMS project aims to produce datasets that are usable by the general archaeological community that addresses what the authors describe as a major issue in archaeological information management. Similar to the findings in this survey, this project found that archaeologists are struggling with producing and creating high quality data that is easily shareable with other communities. As McManamon, et al. (2017) state, these challenges in project data management amount to what they term a 'stewardship gap' (as originally cited in York, Gutmann, and Berman, 2016).

Discussion

Collecting, curating, and managing project data

Collecting, indexing, and making project data available to others within organizations was not perceived as challenging for archaeologists. The most challenging aspects of managing project data for archaeologists were in terms of storing project data and making data available to others outside the organization. Storing archaeological collections safely and sustainably was a major concern for archaeologists who participated in this study. Data was often described as being stored using servers or cloud storage services such as Box and Dropbox. Making collections publicly available is a difficult and sensitive process due to the constraints related to protecting cultural heritage sites from looting. In North America and the United States particularly, sites have been destroyed by looting (Fagan, 2005, p. 64). Making data available to clients and tribes may require contracts or meeting other requirements. Some archaeologists described not making data available outside the organization. Many of the responses echoed the sentiment of this respondent: 'Data is available only on a need to know basis. Digital records are stored on secure data bases with user restricted access, hardcopy is stored under lock and key in a secure room'. These comments point to the difficulty archaeologists face in managing project data successfully and advocating for the importance of archaeological work, while needing to maintain the security of the data and the sites from which those data are collected. When conducting archaeology in North America, public participation, and public knowledge, must be balance with security, liability, and issues of cultural heritage (King, 2001, p. 155-156).

Finally, archaeologists expounded on the methods by which they took notes and acquired data in the field, namely in the context of the technologies they implemented. As mentioned previously, several studies have focused on the use of specific tools and technologies in archaeological work practices, with an emphasis on handheld devices and particular software programs (Ross, et al., 2013; Uildriks, 2016). This work points to the trend for archaeologists to implement technology without, as Caraher (2015) argues, considering the uneven impact of technology on archaeology in terms of human and technology infrastructure. Of those who responded to this questionnaire, six out of twenty-four archaeologists specifically mentioned the use of tablets when asked to describe the processes they use to collect project data. High accuracy GPS units were also mentioned and others mentioned traditional pen and paper notes. While some archaeologists still use traditional methods of field data acquisition, others are certainly using digital technologies in the field. That said, there is a tension between using tools such as iPads and traditional modes of data collection such as note taking. While streamlining data collection in the field is appealing, it is also sometimes impractical, given the nature of fieldwork.

In the next section, we use a specific case to contextualise the challenges faced by archaeologists in project data management in terms of a specific project example.

Handling data: potential for collaboration between archaeologists and information professionals

The majority of archaeologists who participated in the survey described having an interest in collaborating with information professionals. Archaeologists were focused on several specific needs that they felt could be addressed through collaborative effort with information professionals. These resonate with many issues addressed in research that explores issues in data management, data integrity, and the sustainability of data collections over the long-term. As Borgman notes, 'If the rewards of the data deluge are to be reaped, then researchers who produce those data must share them, and do so in such a way that the data are interpretable and reusable by others' (Borgman, 2012, p. 1059). Archaeologists grapple with managing data in such a way that it is replicable and usable by others, while still sensitive to the cultural heritage requirements for preserving archaeological sites. Additionally, by ranking the difficulty of these data management tasks we have begun the work of assessing the information needs of archaeologists. Knowing this, information professionals can focus on potential collaborations on making data accessible and storing project data while de-emphasizing aiding with project data collection, sharing data with co-workers, and describing and indexing data.

The study results show that when information professionals had already collaborated with archaeologists, it was with those in a fairly traditional librarian role, either a collection manager role or in an information seeking capacity. Some participants were outright uncomfortable with working with information professionals due the confidential nature of the data being collected and the need to keep a project location secret. Many archaeologists were interested in working with information professionals, however, particularly in terms of data management and mismanagement and accuracy and accessibility of data over the long term. While it is possible to view these issues as reiterating a divide between the professions, it is important to note that there are some potential roles for information scientists in collaborating with archaeologists. Having subject expertise was not a requirement that archaeologists were concerned about: they wanted someone to help them with processing and using data and contributing to the progression of a project and the growth of knowledge about the history of the communities in which they were working.

The potential role of the information professional as a mediator between archaeologists and other interested parties reflects previous work that has considered librarians as information intermediaries. One potential role of librarians and other information professionals (particularly archivists and data managers) could be to act as an information mediary, or broker, between archaeologists and local government and community organizations (Abrahamson and Fisher, 2007; Abrahamson, Fisher, Turner, Durrance, and Turner, 2008). Helping the public understand the goals of archaeology projects and how communities can be involved is an important aspect of archaeology. However, balancing that outward facing goal is difficult, and there is tension between the need to protect archaeological data while making it available to the public for informational and advocacy purposes. Information professionals could help to ease that tension by acting in this mediating role, as boundary spanners between organizations. This could foster connections between archaeologists and other community members and help archaeologists make data accessible to the public, while still meeting the requirements of preserving that data.

Potential partnerships between information professionals and archaeologists could also foster increased awareness of a community's cultural past, as well as provide avenues for archaeologists to interact with the public directly. For a cultural resource management firm, for example, the role of an information scientist may mirror that of a collections librarian in many ways. That role could involve managing print collections (such as books, maps, reports, etc.) along with project management activities and records. In an academic institution, that role could involve community outreach and education, training on research data management practices and the use of technologies to support those activities as well as advocacy within the academic institution and the broader community. Whatever their role, information professionals have an opportunity to connect with organizations doing the work of archaeology. Another potential area of collaboration is related to training. Several archaeologists requested tips of training on managing large amounts of data, specifically within the context of an organization or a specific project. Information professionals can also act as advocates for the archaeology being conducted within communities to facilitate progress in not just completing projects but in promoting interest and awareness of the culture and history of a community. As one participant noted, archaeologists are limited by government requirements for submitting project data and archaeologists often have disparate formats and processes for collecting and storing data. Information professionals are facilitating dialog between organizations. There is an opportunity for information professionals to lend their expertise, not as archaeologists but as those capable of addressing the major challenges identified in this pilot survey.

Conclusion

Relying on the perspectives of North American archaeologists, this study examined the results of a pilot survey that explored issues related to project data management and the potential for collaboration between archaeologists and information professionals.

The most challenging aspects of data management for archaeologists include acquiring the data in the field, sharing the data with those outside their organization, and storing the data after it has been acquired. While many archaeologists found data acquisition challenging, many were currently using technology such as tablets and high accuracy GPS. While archaeologists' use of this technology may be improved via input from information professionals, many are already facing the challenges of data acquisition via the use of these technologies. Few of the archaeologists surveyed had worked with information professionals, but a majority of respondents were willing to work with them in the future. Those that were not willing to work with information professionals were exclusively found within the private sector. Arguably, collaboration might be more difficult in this realm because those in private sector often work with companies and on projects where information may be proprietary, and even the scope and location of the project may be sensitive information. Having identified some of the most challenging aspects of data management within archaeological science and a willingness of archaeologists to work with information professionals, we feel that there is much potential for collaboration.

One important aspect of the work archaeologists do that was not addressed in this study was the issue of time. The temporal nature of the work performed by archaeologists and the cyclical nature of moving from project to project and field season to field season was not addressed in this pilot survey. Underlying many of the comments shared by archaeologists was a need for immediate help with project management: if today's issues can't be addressed today, then they are going to have to move on to the next project and that project data may not be examined again for decades. Future projects will consider this issue and identify specific points in the project cycle to further explore exactly how information scientists can collaborate with archaeologists.

Overall, our study has revealed several aspects of archaeologists' data management practices and has identified the challenges they face from an emic perspective. Building on this pilot study will involve additional survey of archaeologists in two primary areas. First, our work will emphasize exploring the research data management process as it relates to the implementation of technology in fieldwork practices. It is clear that there is a tension between the use of technology and implementing traditional field data collection methods, and understanding how technology is impacting the data management lifecycle of archaeologists as an important dimension for identifying how to develop the best practices they perceive as essential. Second, we will examine how information professionals perceive the potential for collaboration with archaeologists, with a view to understanding how information professionals can aid in developing sustainable data management practices that allow for the collection, storage, and dissemination of high quality data that is useful to the broader archaeological community.

Note

This study was approved by Simmons University’s Institutional Review Board on February 28, 2018, Protocol #17-098: Archaeologists' project data management practices.

About the authors

Justin P. Williams is a lecturer at Assumption College in Massachusetts and Adjunct Faculty at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. He received his Bachelor’s degree in Anthropology and History from the University of Kentucky, and a Masters and PhD in Anthropology from Washington State University. He can be contacted at: justinpatrickwilliams@gmail.com

Rachel Williams is an Assistant Professor at the School of Library and Information Science at Simmons University in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. She received her Bachelor’s degree in English at the University of Kentucky and her Master’s degree in Library and Information Science at the University of Pittsburgh. Rachel completed her PhD in Library and Information Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She can be reached at rachel.williams@simmons.edu.

References

- Abrahamson, J. A. & Fisher, K. E. (2007). 'What's past is prologue': towards a general model of lay information mediary behaviour. Information research, 12(4), paper colis15. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-4/colis/colis15.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zgVVpn0).

- Abrahamson, J. A., Fisher, K. E., Turner, A. G., Durrance, J. C. & Turner, T. C. (2008). Lay information mediary behavior uncovered: exploring how nonprofessionals seek health information for themselves and others online. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 96(4), 310-323. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2568838 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zlgqsUY).

- Anderson, D. G., Miller D., Yerka, S., Gillam, J.C., Johanson, E. N., Anderson, D. T.,... & Smallwood, A. M. (2010). PIDBA (Paleo-Indian Database of the Americas) 2010 current status and findings. Archaeology of Eastern North America, 38, 63-90.

- Anderson, D.G., Bissett, T.G., Yerka, S.J., Wells, J.J. Kansa, E.C., Kansa, S.W., Meyers, K.N.,... & White, D.A. (2017). Sea-level rise and archaeological site destruction: an example from the Southeastern United States using DINAA (digital index of North American archaeology). PLOS One, 12(11). Retrieved from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0188142 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/77PIpbthV)

- Bates, M. J. (1999). The invisible substrate of information science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50(12), 1043-1050. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/asi.22634 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zgwTXPT).

- Beaudoin, J. E. & Brady, J. E. (2011). Finding visual information: a study of image resources used by archaeologists, architects, art historians, and artists. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 30(2), 24-36.

- Borgman, C. L. (2012). The conundrum of sharing research data. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(6), 1059-1078. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/asi.22634 (Archived by WebCite ® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zgwTXPT).

- Bradley, B., Collins, M. B., Hemmings, A., Shoberg, M. & Lohse, J. C. (2010). Clovis technology. Ann Arbor, MI: International

- Buchanan, B. & Collard, M (2007). Investigating the peopling of North America through cladistic analyses of early Paleo-indian projectile points. Journal of anthropological archaeology, 26(3), 366-393. Retrieved from http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/5211 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zhNKpkF).

- Caraher, W. (2015). Slow archaeology: technology, efficiency, and archaeological work. In Erin Walcek Averett, Jody Michael Gordon, and Derek B. Counts, (Eds.). Mobilizing the past for a digital future: the potential of digital archaeology (pp. 421-441). Grand Forks, ND: The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota. Retrieved from https://dc.uwm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=arthist_mobilizingthepast (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/77PP3QPzd)

- Ellis, S. J. (2016). 1.2. Are we ready for new (digital) ways to record archaeological fieldwork? a case study from Pompeii. In Erin Walcek Averett, Jody Michael Gordon, and Derek B. Counts, (Eds.). Mobilizing the past for a digital future: the potential of digital archaeology (pp. 51-75). Grand Forks, ND: The Digital Press at the University of North Dakota. Retrieved from https://dc.uwm.edu/arthist_mobilizingthepast/4 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zhlCrT9).

- Ellis, D. & Haugan, M. (1997). Modelling the information seeking patterns of engineers and research scientists in an industrial environment. Journal of documentation, 53(4), 384-403.

- Fagan, B. (2005). Ancient North America. 4th ed. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson.

- Faniel, I., Kansa, E., Whitcher Kansa, S., Barrera-Gomez, J. & Yakel, E. (2013). The challenges of digging data: a study of context in archaeological data reuse. In Proceedings of the 13th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital libraries (pp. 295-304). New York, NY: ACM.

- Faniel, I. & Yakel, E. (2017). Practices do not make perfect: disciplinary data sharing and reuse and their implications for repository data curation. In Curating research data. Volume one: practical strategies for your digital repository, (pp. 103-126). Chicago IL: Association of College and Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.oclc.org/research/publications/2017/practices-do-not-make-perfect.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76KM4jruY).

- Hamilton, M. J. & Buchanan, B. (2009). The accumulation of stochastic copying errors causes drift in culturally transmitted technologies: quantifying Clovis evolutionary dynamics. Journal Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 55-69. Retrieved from http://www.unm.edu/~marcusj/Hamilton%20and%20Buchanan%202009.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zi4Xvyb).

- Haynes, G. (2002). The early settlement of North America: the Clovis era. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Huvila, I. (2011). The politics of boundary objects: hegemonic interventions and the making of a document. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 62(12), 2528-2539. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0ec2/2eea82d5673cee7dba6d08a4127d2d587850.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75ziV8YiT).

- Huvila, I. (2014). Archaeologists and their information sources. In Isto Huvila, (Ed.). Perspectives to archaeological information in the digital society, (pp. 25-54). Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University. (Meddelanden från Institutionen för ABM vid Uppsala universitet, Nr. 5). Retrieved from http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:776286/FULLTEXT01.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zicxeJw).

- Huvila, I. & Huggett, J. (2018). Archaeological practices, knowledge work and digitalisation. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, 1(1), 88-100. Retrieved from https://journal.caa-international.org/article/10.5334/jcaa.6 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zikE97S).

- Kansa, E., Kansa, S. W. & Arbuckle, B. (2014). Publishing and pushing: mixing models for communicating research data in archaeology. Internatinal Journal of Digital Curation, 9(1), 57-70.

- Kansa, E.C., Kansa, S.W. , Wells, J.J. , Yerka, S.J. , Meyers, K.N., Bissett, T G. & Anderson, D.G. (2018). The digital index of North American archaeology (DINAA): networking government data to navigate an uncertain future for the past. Antiquity, 92(363), 490-506.

- King, T. F. (2001). Federal planning and historic places: the Section 106 process. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press,

- Kulasekaran, S., Trelogan, J., Esteva, M. & Johnson, M. (2014) Metadata integration for an archaeology collection architecture. In International Conference on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications, Austin, Texas, 8-11 October 2014, (pp. 53-63). Retrieved from http://dcpapers.dublincore.org/pubs/article/viewFile/3702/1925 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zj6Fn35) .

- McManamon, F.P., Kintigh, K.W., Ellison, L.A. & Brin, A. (2017). tDAR: a cultural heritage archive for twenty-first-century public outreach, research, and resource management. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 5(3), 238-249.

- Meltzer, D.D. (2004). Peopling of North America. In A. R. Gillespie, S.C. Porter and B.F. Atwater, (eds.). The quaternary period in the United States, Vol. 1., (pp. 539-569). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science.

- Morrow, J. E. & Morrow, T.A. (1999). Geographic variation in fluted projectile points: a hemispheric perspective. American Antiquity, 64(2), 215-231. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2694275 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zjHke2d).

- Olsson, M. (2016). Making sense of the past: the embodied information practices of field archaeologists. Journal of information science, 42(3), 410-419. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0165551515621839 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zjabWhE).

- Prasciunas, M. (2011). Mapping Clovis, projectile points, behavior, and bias, American antiquity, 76(1), 107-126. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-antiquity/article/mapping-clovis-projectile-points-behavior-and-bias/1394EEDBB038284A7B0017EF319CADC6 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zjgozC2).

- Ross, S., Sobotkova, A., Ballsun-Stanton, B. & Crook, P. (2013). Creating eresearch tools for archaeologists: the federated archaeological information management systems project. Australian archaeology, 77(1), 107-119. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03122417.2013.11681983 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zk2pN9o).

- Sanchez , G., Holliday, V. T., Gaines, E. P., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., Martínez-Tagüeña, N., Kowler, A., Lange, M. ... & Sanchez-Morales, I. (2014) Human (Clovis)–gomphothere (Cuvieronius sp.) association ∼13,390 calibrated yBP in Sonora, Mexico. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(30), 10972-10977.

- Uildriks, M. (2016). iDig-Recording archaeology: a review. Internet Archaeology, 42. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.42.13 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zkU19In).

- Waters, M.R. & Stafford, T.W. (2007). Redefining the age of Clovis: implications for peopling of the Americas. Science, 315(5815), 1122-1126. Retrieved from http://science.sciencemag.org/content/315/5815/1122 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zku2Tsa).

- Williams, J.P. (2016). Morphological variability in Clovis style hafted bifaces from across North America. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Washington State University, Pullman, Washington, USA.

- Yerka, S.J., Echeverry, D., Anderson, D.G. & Miller, D.S. (2012). Redesigning PIDBA (The Paleoindian Database of the Americas): enhancing the accessibility of information and the user experience. Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, April 19, 2012, Memphis, Tennessee. Retrieved from http://pidba.org/content/SAA2012.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/77PUewm8s)

- Yerka, S.J., Myers, K.N., DeMuth, R.C., Anderson, D.G., Kansa, S.W, Wells, J.J. & Kansa, E.C. (2015). Built to last: the Paleoindian Database of the Americas (PIDBA) and openly-shared primary data meet the digital index of North American archaeology. Poster presented at the 2015 Society of American Archaeology Meeting, San Francisco, California. Retrieved from http://pidba.org/content/SAA2015.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/77PayotoF)

- York, J., Gutmann, M. & Berman, F. (2016). What do we know about the stewardship gap?. Retrieved from https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/122726 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/75zl8ISOy).

How to cite this paper

Appendix 1: Archaeologists' Project Data Management

Start of block: Survey instruction

Q1: Informed Consent

- I consent, begin the study (1)

- I do not consent, I do not wish to participate (2)

End of block: informed consent

Start of block: demographic information

Q2 What is your position title? ________________________________________________________________

Q3 What kind of organization do you work for? ________________________________________________________________

Q4 Number of years of experience in current position: (Please click and drag the slider to indicate the number of years.)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Click to write Choice 1 (1)

Q5 Number of years of experience in archaeology (Please click and drag the slider to indicate the number of years.)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Click to write Choice 1 (1)

Q6 Please describe what your current position responsibilities include.

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

End of Block: Demographic Information

Start of Block: Project Data Collection

Q7 Please describe the process(es) you use to collect project data. Examples of project data include artifact data, site maps and location information, and project notes.

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

End of block: project data collection

Start of block: project data management

Q8 Please describe your process(es) for managing project data (Where do you store data? How do you describe and index project data? How is it made accessible to coworkers inside your organization? To people outside your organization?)

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

Q9 Click to write the question text

Not at all challenging (1) A little bit challenging (2) Somewhat challenging (3) Very challenging (4)

- Collecting project data (1)

- Describing/indexing project data (2)

- Click to write Statement 6 (3)

- Storing project data (4)

- Making project data accessible to coworkers inside my organization (5)

- Making project data accessible to professionals outside my organization (6)

End of block: project data management

Start of block: collaboration with information professionals

Q10 Have you ever worked with an information professional? An information professional is someone who collects, records, organizes, stores, preserves, retrieves, and disseminates printed or digital information. The term is most frequently used interchangeably with the term 'librarian', or as a progression of it.

- Yes (1)

- No (2)

Display this question:

If Have you ever worked with an information professional? An information professional is someone who... = Yes

Q11 In what way did you work with an information professional, or librarian? Please select all that apply.

- A librarian searched for information for me. (1)

- A librarian was/is on staff in my organization. (2)

- A librarian helped manage project data for my organization. (3)

- A librarian helped manage books and other materials for my organization. (4)

- Other (5) ________________________________________________

Q12 Are you interested in collaborating with information professionals to help manage project data? An information professional is someone who collects, records, organizes, stores, preserves, retrieves, and disseminates printed or digital information. The term is most frequently used interchangeably with the term 'librarian', or as a progression of it.

- Definitely yes (1)

- Probably yes (2)

- Might or might not (3)

- Probably not (4)

- Definitely not (5)

Display this question:

- If Are you interested in collaborating with information professionals to help manage project data? A... = Definitely yes

- Or Are you interested in collaborating with information professionals to help manage project data? A... = Probably yes

- Or Are you interested in collaborating with information professionals to help manage project data? A... = Might or might not

- Or Are you interested in collaborating with information professionals to help manage project data? A... = Might or might not

Q13 In what ways do you think an information professional would be a valuable collaborator?

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

Q14 Did we miss anything? Please use this space to share anything else about your work, your processes related to project data management, or your interests in collaborating with information professionals:

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________