Collaborative information seeking during leisure travelling: triggers and social media usage

Jannatul Fardous, Jia Tina Du and Preben Hansen.

Introduction. Tourists travelling in groups tend to search for information in collaboration with tour mates and on social media. However, collaborative information seeking during group travelling has been relatively understudied. This paper aims to investigate the triggers that prompt collaboration between tour mates, and to identify the circumstances of social media usage in such collaboration.

Method. The in-depth group interviews were conducted with thirty-four tourists (twelve travel groups) who had taken group trips in the past three months.

Analysis. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyse interview transcripts. The data were categorised and sub-categorised through open coding.

Results. The results revealed that, during travel, tourists collaborated to seek, share, and synthesise information and make group decisions to reschedule on-site travel activities and to coordinate the tour group (e.g., managing preferences and conflicts). Our study found that social media played a vital role for a group of tourists under a variety of circumstances, including re-planning the trip, sharing travel updates and queries, obtaining up-to-date local news, and communicating with tour mates and families and friends back home.

Conclusion The findings of this study may advance our understanding of the dynamic online information needs and information seeking in a group setting.

Introduction

Collaboration is useful and often required when people work as a group, especially when one of their goals is to seek information together to satisfy a common information need (Shah and Marchionini, 2010). Researchers have argued that when people work in a group, they can accomplish more tasks, benefit from other people’s experiences and expertise on the given topic, influence one another, and develop a more profound understanding of the subject than when they are isolated (Shah, 2014). We refer to collaborative information seeking and sharing as the situations in which multiple people interact and share information with each other to solve a shared problem in a team setting (Fardous, Du, Choo, Huang and Hansen, 2017; Hansen and Järvelin, 2005). Trip planning is an important situation in which this occurs (Mohammad Arif, Du and Lee, 2015; Shah, 2014). Nevertheless, limited research has been done to study tourists’ collaborative information seeking behaviour during leisure travelling, which occur during the period of time between starting a group trip and returning to home.

In fact, more and more tourists nowadays tend to travel with family, relatives or friends (Schänzel and Yeoman, 2015). For travellers who organise their group trip by themselves, trip planning involves information-intensive activities such as information seeking, sharing, assessing, and sense-making, as well as coordination between tour mates to reach agreements and to make collaborative decisions. Information seeking and decision-making may take place in both the initial trip planning stage and during leisure travelling (Fardous, et al., 2017; Mammadov, 2012; Morris, 2008). When tourists travel, looking for independent sources of information, such as reviews of dining experiences on social media (e.g., blogs), may help them make an informed and quick decision on where to eat (Rezdy, 2016). However, our understanding of how a group of tourists uses social media to fulfil their dynamic and common information needs during travel is inadequate.

In recent studies, tourists have been found to turn to user-generated content (e.g., experiences and reviews posted on social media) when researching a new destination (Harrigan, Evers, Miles and Daly, 2017). This content is perceived as similar to recommendations provided by friends, family members or like-minded people (Wang, Yu and Fesenmaier, 2002; Xiang, Wang, O’Leary and Fesenmaier, 2015) and thus have become a trustworthy source of information for prospective tourists. Specifically, researchers have found that, during the travel planning stage, tourists searched for ideas about where to go, accommodation options, transportation, and leisure activities on social media (Cox, Burgess, Sellitto and Buultjens, 2009; Fotis, Buhalis and Rossides, 2012). The availability of experiential tourism information on social media platforms has made them an influential tool for tourists. A recent study by Fardous et al. (2017) suggested that tourists interacted with others on social media using their mobile devices to seek, gather, obtain, share and validate tourism information for trip planning. Tourists have also been found to change their initial travel plans due to the influence of interactions on social media.

Tan and Goh (2015a) found that, while travelling, an individual tourist uses his or her social interactions to find information and that such interactions spontaneously affect their information seeking and decision-making processes. These social interactions helped travellers get to their intended tourist destinations and enrich their travel experiences (Mammadov, 2012). Yet we have a limited understanding of how a group of tourists utilises social media, and how it influences their travelling experiences when they are on holiday.

In this study, we consider collaborative information seeking to be a situation in which team members seek, share, evaluate, and validate travel information together to fulfil their informational needs and make on-site collaborative decisions. The role of social media is defined as the use of social media for group travel-related purposes when tourists are at the destination. Specifically, we address the following two research questions:

RQ1. What are the triggers for tourists’ collaborative information seeking behaviour while they are holidaying at the selected destination? How do they collaborate during these activities?

RQ2. What are the circumstances of social media use during group travelling? What role does social media usage play in collaborative information seeking while tourists are executing a group trip?

Related works

Triggers in information seeking

Information seeking is an activity involving cognitive processes such as learning and problem solving rather than simply retrieving information (Marchionini, 1989). Information needs have been identified as the main trigger of initial information seeking and the driver that keeps the information-seeking process in motion (Savolainen, 2017; Wilson, 1999). Cheverst, Davies, Mitchell and Friday (2000) defined this type of trigger as the need or reason that establishes an information seeking event. Research has shown that lack of expertise, lack of immediately accessible information, and complexity of information need all act as triggers during collaborative information seeking (Reddy and Spence, 2008). Recently, Tan and Goh (2015a) described triggers as the moment when information seekers were unable to satisfy information needs on their own and initiated the move from individual information seeking to collaborative information seeking . The authors presented a set of ten triggers leading to collaborations with intra-group and inter-group people for seeking information, such as the lack of information seeking skill, lack of subject knowledge, tapping on the team’s or external parties’ experiences and background knowledge, requiring confirmation with others, requiring help in complex tasks, finalising one decision among multiple choices or opinions, resolving conflicts found in direct sources of information, individual’s interest to know more about a topic, and change in context. Besides, joint decision-making was found to act as a trigger for tourism activities in group vacation planning since tourism activities are intensively group-based (Decrop, 2005). Limited research, however, has investigated the triggers for collaborative tourist activities during travelling. For example, it is unclear what triggers the collaboration between tour mates to fulfill group information needs during group travelling.

Social media in information seeking

Social media are a group of Internet-based applications (e.g., social networking sites, consumer review sites, content community sites, wikis, Internet forums, and location-based social media) in which people interact, create, share, and exchange information and ideas with virtual communities and networks (Zeng and Gerritsen, 2014). Thus, it has changed people’s minds and emerged as a new way to find information by utilising social interactions or relationships between people on the Web (Kim, Sin, and He, 2013; Morris, Teevan, and Panovich, 2010). In recent years, the reliance on social media for information has increased significantly in everyday life due to the high level of interactions between users and trustworthy information sharing nature. For example, a study by Gauducheau (2015) explored how forums provide teenagers peers’ opinions and verifiable information on personal matters with a way of overcoming information seeking difficulties and finding specialised information. Patients who need self-management and care can benefit from using social media regularly. Shaw and Johnson (2011) revealed that people with chronic illness (e.g., diabetes) used blogs, YouTube, Twitter, and discussion groups and forums to seek and discuss disease-related information. In the academic context, social media has become an increasingly popular platform for international students to obtain a variety of information on academic, financial, sociocultural and health-related topics (Hamid, Bukhari, Ravana, Norman and Ijab, 2016). People also use social media to gather relevant information during crises such as riots, flu outbreak, earthquake, and flood. Austin, Liu, and Jin (2012) found that people preferred to use social media for insider information and to check in with family and friends during the crises because of the convenience, involvement, and personal recommendations.

Social media in tourism information seeking

With the rapid growth of social media, and given the experiential nature of tourism, information shared on social media plays a vital role for tourists while planning, booking tourism products and services, and executing a trip (Parra-Lopez, Gutierrez-Tano, Diaz-Armas, and Bulchand-Gidumal, 2016). In particular, prospective tourists increasingly turned to social media such as blogs, as they are more interested in getting tips from experienced travellers using online resources than physically visiting travel agencies and visitor information centres (Virtue, 2014; Volo, 2010). Moreover, as the contents on social media are recent and contemporary, search engines (e.g., Google) also direct tourism information seekers to social media pages to acquire information including consumer-generated contents and many useful hyperlinks (Xiang and Gretzel, 2010).

A recent study by Kim, Lee, Shin, and Yang (2017) explored the role of tourism information quality on social media for potential tourists to form both cognitive and affective destination images. A piece of complete travel information was found to help travellers create the cognitive side of destination image including what to do and where to find things. Thus, experienced travellers’ information influenced other tourists’ decision-making process about destinations, hotels, and related products. The trustworthiness of information on social media mainly influences tourists while planning and searching for information (Leung, Law, van Hoof and Buhalis, 2013). For example, Hudson and Thal (2013) found that user-generated contents (e.g., online reviews of hotels or destinations) have a significant impact on the evaluation stage, which leads to adding or subtracting tourism-associated products (e.g., hotels, restaurants, transports) according to their requirements. Social media has become a popular platform for tourists seeking information, even when travelling, when a crisis occurred (Schroeder and Pennington-Gray, 2015). In this paper, we attempt to examine the use of social media in tourist collaborative information seeking behaviour during travelling.

Research method

Semi-structured group interviews were employed to explore the role of social media usage during group information seeking when travelling. The group interviews aimed to find both the facts and meanings of stories underlying experiences of participants (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2009). In this study, in-depth interviews helped obtain detailed descriptions of the interactions between a group of tourists who travelled together and their reasons behind their social media use for trip-related purposes. The group interview method was chosen over other methods because it would be difficult to empirically observe a tourist group’s behaviour while using social media and interacting with other tour members while travelling because of privacy concerns. Furthermore, a quantitative method like a survey is able to show a statistical inference of data but not able to provide in-depth data based on these complex group processes (Lazar, Feng and Hochheiser, 2017). Nevertheless, there are limitations of group interviews. It is time-consuming and costly. Also, not all members participated in the group interview, which is reflected in the data of Table 1.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with participants in each tour group to find out details associated with collaborative information seeking during travelling. Postgraduate students and researchers working in an information technology school of a large university in South Australia were recruited from university e-mail lists. Advertisements were also posted on the notice boards on the university campus. Friends of the researchers who had a recent group trip were also approached in person and through Facebook. Participants were professionals including teachers, sales representatives and information technology professionals. A snowball technique (Neuman, 2011) was adopted; participants were requested to propose participation to other eligible people. The interviews were undertaken at each group’s convenience and lasted between 50 and 70 minutes on average. Participants were asked to talk about their experiences of recently completed group travel, trip-related collaborative activities, circumstances of social media use during group travel, and their perceptions of the effect of social media use on their group travel experience. All interviewed groups were independent travellers in terms of organisation of their trips and had travelled with a group of people in the previous three months. A gift voucher of AUD10 (a music group) and a box of chocolate were presented to each participant as compensation. A total of thirty-four participants from twelve groups took part in the interviews. Among them, four groups consisted of family members and eight groups were composed of friends. The group size ranged from two to five. The average age of the travel group was thirty years old. The majority of them (91%) utilised smart mobile devices (smartphones and tablets) during travelling. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed later for analysis. Table 1 summarises the participants’ demographic information.

| Travel group | Group size | Interview participants | Average age of the group |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Family group) | 5 | 4 | 27 |

| B (Family group) | 5 | 3 | 32 |

| C (Family group) | 3 | 2 | 43 |

| D (Family group) | 3 | 3 | 32 |

| E (Friends Group) | 4 | 3 | 26 |

| F (Friends group) | 4 | 3 | 33 |

| G (Friends group) | 2 | 2 | 24 |

| H (Friends group) | 5 | 3 | 29 |

| I (Friends group) | 6 | 3 | 25 |

| J (Friends group) | 4 | 3 | 25 |

| K (Friends group) | 3 | 2 | 38 |

| L (Friends group) | 2 | 3 | 26 |

| Total: 12 groups | 46 | 33 | 30 (average) |

Data analysis

Qualitative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) was used to analyse the transcribed interviews. The data were examined to identify the categories, sub-categories, and respective explanations and their relation to collaborative information seeking and related social media usage. Categories and patterns emerged from the coding process of the data, rather than being imposed beforehand. During the analysis, the data were analysed through a series of steps using open, axial, and selective coding (Berg, 2001). Initially, the data were read thoroughly and carefully, and basic practices and concepts were identified in open coding. Next, in axial coding, the data were reread and organised according to the categories and sub-categories and finally, in selective coding, all the concepts and categories were brought together to develop the final themes. In this study, the coded logs were used to determine the triggers that prompted collaborative information seeking within the group during travelling, the means for collaboration with tour mates, and the circumstances and roles of social media usage. Finally, selective coding was performed to answer the research questions during which all categories and sub-categories were unified under a core category that represented an important phenomenon. The original data were reviewed thoroughly multiple times to ensure that no data were missed.

Results

In this section, we present our results based on the analysis of the interview data to address the research questions.

Triggers for collaborative information seeking behaviour within the group

When a group of participants travelled, there were certain situations when they worked together to continue the group trip seamlessly. As reviewed in the related studies, a trigger is an event that initiates a particular action, process, or situation of collaborative information seeking associated with continuing the trip. Two main types of triggers were found, which prompted collaboration between tour mates to solve their travel-related issues, including re-planning trip activities and managing the travel group (Table 1).

Re-planning trip activities

All interviewed participants reported that they altered and made group decisions regarding on-site tourism products and activities such as visiting places, restaurants, routes, transportation, bike riding, and skiing because of local weather conditions, disagreements of preferences, participants’ health conditions, and conflicts in timing between activities. Therefore, collaborative information seeking was triggered when the travel group needed to re-plan some parts (e.g., activities and attractions) during the trip. The outstanding trigger of group task relating to re-planning of the trip was seeking and sharing a wide range of on-site tourism information to alter the pre-planned itinerary (Table 2). Participants mentioned that they sought information from other members of the group to learn and gather more relevant information regarding aspiring activities. For instance, information about history, background and reviews of tourists’ spots (temple, museum, Taj Mahal, shopping mall, and Fuji Mountain), restaurants (vegetarian cuisine, and Italian gourmet pizza), route (hotel to tourists’ spots, and restaurants) and transportation (bus, train, rent-a-car, etc.) were solicited from and shared with each other in the tour group to inform everyone of the probable alternatives. Also, participants shared links of Facebook pages operated by various travel groups and service organisations (e.g., Facebook pages of Bangladeshi travellers, Kayak and booking.com), images and videos of places they visited, and activities (chopper rides, tobogganing and theme parks), names and addresses of temples, cities and shopping malls, and ideas and thoughts with their group members so that everyone could have detailed knowledge and understandeach member’s thinking before making the final decision. As one group stated:

We changed our original plan [botanical garden to Sydney aquarium] because one member became sick and he [the unwell member] didn’t want to walk in the sun. So, we had to search information to plan again and searched information on Facebook pages and blogs. We shared search results and opinions with each other to let people know what were found. (Group B)

Another trigger related to re-planning of the trip was the synthesizing of information shared by team members (participants of the same group). The interviewees stated that they gathered necessary travel information (e.g., names and addresses of tourist spots, and restaurants) by searching online or seeking from experienced tourists independently. After that, the team-mates shared the obtained information to their chat group (Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and WeChat) as well as meeting face-to-face to discuss and compare various factors, such as distance and types of transportation from the hotel, cost, and worth of visit. The reason behind the synthesis of information was to bring up diversity in ideas and views to assure enjoyable and fruitful travel experiences for all. One group commented on this:

Particularly in the morning, we searched up for what to do as our own and posted it [everyone’s proposal] in the Facebook group. After having breakfast, we used to meet in the hotel’s lobby to discuss all members’ opinions to finalise and starting point of sightseeing places and activities for that day. (Group I)

Making alterations on tourism activities and attractions was another significant trigger connecting to re-planning of the trip to ensure that everyone in the team was happy with and could become part of the new choice of activities. In a group setting, there were often several ideas and options for each travel activity, as every tour mate provided his or her preferences. Participants were found to collaborate with tour mates to narrow down their choices to make the final selection by cross-checking with every one of the team including children. A voting system (e.g., yes or no) was sometimes used throughout the process to shorten the list of choices and make a decision. For example, a group stated:

When we travelled to India, we didn’t take any wrong decisions because we filtered information together and took all decisions if everyone was happy with that. We think two minds are better than one. (Group B).

Managing the travel group

Organizing the travel group was the second trigger type that prompted participants to collaborate with their tour partners while on holiday (Table 2). Coordinating the group members was the most common reason to initiate collaboration between members. All interviewees had experience collaborating with group members on a regular basis, particularly in the morning to fix the time to have breakfast, to select the location (e.g., hotel lobby or room) for last-minute group discussion, and to set time to leave the hotel for executing the day-to-day travel activities. For example, a group said:

We used to send message[s] to our entire group (Facebook group) to coordinate the group. In the morning, we sent time (7:30 am) to come at hotel lobby to discuss and know everyone’s opinion for deciding which places we go first, take breaks for refreshments and when come back to hotel. (Group I)

Making on-site trip-related decisions was reported by participants, which included decisions about food through in-person group conversations during each meal, bearing in mind all of the teammates’ opinions and recommendations. Also, they went through the reviews of other diners on social media (Facebook pages and apps), as well as suggestions from the experienced known tourists while selecting a menu and restaurant. One group said:

One of my friend[s] suggested me an App (e.g., Swiggy) to search for restaurants with reviews, menus, price, opening and closing time, distance from our hotel and map to get there. After researching a few restaurants, we proposed the name and services to the group in order to know their opinions and chose one of them. (Group G)

During a holiday, solving conflicts between tour mates also triggered a need for face-to-face collaboration. All participants expressed that they arranged team meetings to work out on the arising conflicts of preferences for visiting places (temple, museum, snowy mountain, island, and park), sites to rest at and who should drive to reach a destination, type of restaurants (fast food, Chinese, pizza, and Indian vegetarian), and mode of transportation from airport to hotel and hotel to tourist spots (taxi, train, and bus). In a worst-case scenario, participants split into two groups according to the different preferences and performed accordingly. It is worth noting that the voting process (e.g., go with the majority of opinions) played a vital role resolving difficult conflicts. For example, one group commented:

We had some conflicts when driving from Adelaide to Melbourne. For example, when we were going to Melbourne, two members wanted to take a break at every 200 kilometers, but rest of the members wanted to take a break once or twice on the whole way to reach early in Melbourne. We went with the second option due to the majorities. (Group H)

| Triggers | Collaborative information seeking activities | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Re-planning trip activities | Seeking and sharing information | Participants seek and share travel information from other participants in the same group while re-planning their trip |

| Synthesising information | During re-planning of the trip, participants collaborate with other group members to synthesise gathered travel information | |

| Making alterations | Participants collaborate within the group to make alternative travel activities | |

| Managing the travel group | Coordinating the group | Participants frequently collaborate daily with the group to coordinate group activities |

| Making on-site trip-related decisions | Group members discuss with each other to make any on-site collaborative decisions | |

| Solving conflicts of preferences between group members | Participants meet together to resolve their conflicts of preferences on travel activities |

Ways and tools used for collaborative information seeking

Collaboration is a process during which group members work together and use their diverse range of knowledge and expertise to solve a common problem (Shah, 2014). Our results revealed that when participants were travelling, the modes and tools for collaboration completely depended on their convenience (e.g., co-located or remote), types of information needs (e.g., links of websites, or names of attractions or visual information), kind of contribution (e.g., giving opinions by mentioning yes or no or proposals), and urgency of information needs (e.g., instant decision-making). For example, all of the participants mentioned that they met in person with their group mates to seek and share information (e.g., proposal, idea, and opinion), solving conflicts in travel-related issues (e.g., on-site visiting places, restaurants and fixing time) as well as making collaborative decision considering individual preferences (e.g., selecting travel activities). They also expressed that face-to-face meeting aidedthe group decision-making process ( e.g., final selection of restaurant, transportation, and things to do and places to go) through watching facial expressions of others. The following quote elucidates the use of collaborative methods for intra-group collaboration.

When we had enough time to plan and need [needed] to inform other tour mates about what to do in next days, we used WeChat. We sit together and discuss face-to-face to make faster decisions when we had to plan for the next day’s activities. (Group B).

Six groups utilised social media including Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and WeChat to seek and share various types of online information (e.g., links of blogs, Facebook pages, websites, images, videos, and opinion as vote, and travel itineraries) so that other members of the group were aware of the recent changes about to occur in their planning, types of information needs, and status of other members. Moreover, participants used social media as collaborative tools when they had enough time to research and assess travel information to reschedule their travel activities and attractions. The reason for collaborative tool selection was explained by one group:

We shared our choices and discussed everything together (face-to-face) because we stayed together all the time. We also shared images of Mount Fuji by Facebook Messenger to see and select the best lookout point to go. (Group D)

It can be concluded that different types of collaborative tools play a significant role in intra-group communication in order to alter the pre-planned trip activities, as well as manage the entire travel group throughout the trip.

Circumstances of social media usage for collaborative information seeking

A circumstance is referred to as a situation in which social media was used. The analysis of interview transcripts revealed four categories of circumstances of social media usage during holidaying at the destination: a) re-planning the trip, b) sharing information, c) getting updates of news and people, and d) communicating with people. Each category consists of two subcategories, as shown in Table 3.

Circumstances related to re-planning the trip

As mentioned, all twelve groups went through the re-planning phase to alter visiting places and restaurants because of lousy weather, conflicts in the timing of multiple events, participants’ physical condition, and spare or a shortage of time after performing the original scheduled activities.

Two specific social media usage circumstances related to re-planning of the trip were identified: seeking and gathering of customised ideas and information, and cross-checking the required information. The most common circumstance related to re-planning was seeking and gathering tailored information. Twenty-five participants reported that they sought and gathered specific tourism information using social media. Specifically, they searched for the opening and closing times of museums, the best route to the hotel from the airport, the best transportation, and showtimes of movies by browsing tourists’ experiences on different blogs and communicating with experienced tourists on social media to sort out their next activities immediately. The underlying reason for using travel blogs, forums and Facebook pages of various travel groups was that social media facilitates and presents diverse experiences of many tourists. The following quotes demonstrates the seeking and gathering of information during travel from social media:

When we reached in Dubai airport, I (a member of the group) was running to exchange currency that was near to me and searched information about it (money exchanger). I found bad reviews on that and suggested another money exchanger within 0.5 km distance that was the biggest one and offer[ed] [the] best rate among all exchangers in Dubai. (Group A)

During our holiday in Italy, I (a member of the group) have read some comments of others from blogs to get information, for example, time when I need to leave hotel to get there (museum) and how many hours I need to visit the museum. (Group F)

Half of the participants also mentioned that cross-checking required information through social media helped them make informed decisions when choosing tourists’ spots, activities, restaurants, and route. Participants needed to make informed decisions because they were travelling at their holiday destination for the first time and everything associated with their trip was new to them. For example, two groups explained:

We always checked on the restaurant before we go there. We read reviews and recommendations to decide on the restaurants. In addition, we used to cross-check about the cost of foods (expensive or cheaper) through reviews as we don’t know anything about the type of restaurant and price of foods. So, when travelling, we want to make sure second time on every activity via other’s experiences as we don’t live in the city. (Group I)

We used Google Maps to figure out the routes of destination (routes of going to tourist’s spots, restaurants, hotels, and shopping) to keep checking whether the route was right or wrong even though the taxi driver knew the destination. Because we wanted to ensure that we didn’t lost our way to reach the destination. (Group C)

| Category | Sub-category | Description | No. of participants | No. of groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re-planning the trip | Seeking and gathering tailored information | Tourists seek and gather tailored information through social media to re-plan travel activities during the trip | 25 | 12 |

| Cross-checking information | Cross-check travel-related information during re-planning trip activities during the trip | 16 | 10 | |

| Sharing information | Sharing experiential travel activities with family and friends | Social media is used predominantly by tourists to share their ongoing travel activities with their family members and friends | 17 | 11 |

| Sharing post to seek travel suggestions | Tourists used social media to share or post queries to seek travel suggestions on particular topics during the trip | 3 | 3 | |

| Getting updates | Getting updates on local news and events | Tourists used social media to get local news and information on events that are going on at the destination | 9 | 7 |

| Getting updates on family and friends | Social media updates tourists with recent activities performed by their family members and friends | 12 | 6 | |

| Communication | Keeping in touch with family and friends | Tourists used social media to keep in contact with their family members and friends while they were travelling | 22 | 12 |

| Collaborating with tour mates | Social media is utilised by tourists to collaborate with accompanying tourists during the trip | 24 | 8 |

Circumstances related to sharing travel information

During the trip, social media was often used to share travel-related information. In this study, sharing experiential travel information is defined as social media posts that contain opinions and emotions (happiness or sadness) along with photos or videos about places, traditional local food , and information and advice on safety (e.g., be careful about theft if you visit this park). In this regard, 17 (50%) participants mentioned that they shared images, videos, location information, and experiences about their trip on social media because they wanted to show their travel activities to family and friends, to store these good memories, and to provide useful travel information for future travellers. Two groups commented:

I did keep posting on Facebook and Snapchat throughout my trip. I did this to share with my friends about the amazing places I visited, and great food I eat, etc. I tagged my mom so that she doesn’t need to post. (Group G)

I posted some pictures including The University of Sydney, Sydney Opera House, Darling Harbor, Sydney Harbor Bridge, Bondi beach on WeChat and Facebook. Because the scenery in these places is very beautiful and amazing, I want to share it with my friends and family. (Group L)

It is worth noting that participants also posted queries on social media to inquire about specific travel questions because of the lack of domain knowledge within the whole group. Particularly, three participants posted queries on WeChat and Facebook to obtain information, as their groups were not familiar with a particular topic related to their trip. For example, two groups stated:

When we were in Brisbane, I (one of the group members) posted a query on baidu and got many replies. Some of the replies were very useful. For example, I posted “How to get refund of Metro card” and I got a useful reply that I can post the card to certain address even after reaching home. (Group B)

I (one of the group members) posted a query on TripAdvisor to know about the price of the hotel and services, and the best offer they can provide me within my budget. (Group C)

The trend of tourists sharing trip-related experiences, good or bad, on social media might inspire prospective tourists to make a proper trip plan. Tourists also solved particular problems they encountered during the trip based on the suggestions received through social media.

Circumstances related to getting updates

Getting updates on local news and events played an important role in the participants’ use of social media during the trip. Participants gathered information about crisises, safety and security of transportation nightclubs, local events (e.g., fairs and festivals) and weather reports. Nine participants expressed interest in the local news as the main reason for utilising social media during the trip. Participants said:

I checked information about Philip Island (when the island is open and we can see penguins). I found we had to go [starting time] there in the evening and wait until midnight to see penguins. We changed our plan to go to Philip Island after our group discussion due to the bad timing [midnight]. (Group C)

We also looked up for local news and weather over there. (Group J)

Participants can also use social media to update friends and family members. Twelve (35%) participants reported they always used social media like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and WeChat whenever they could to check statuses, photos, and videos posted by dear ones, and to receive notifications of upcoming events and birthdays of others. One group mentioned:

We always see newsfeed on Facebook to check updates on my friends and family back home throughout my travel in India.’ In this case, getting updates about friends and family members are not directly related to tourists’ ‘travels, but such updates may ensure tourists to experience the trip with peace of mind. (Group K)

Circumstances related to communication

The ubiquitous use of smart mobile devices has made social media readily accessible, and therefore it plays a key role in participants’ communication with other people. During the trip, twenty-two participants employed social media (e.g., Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and WeChat) to talk with family members and friends to report on their travels and to obtain travel-related suggestions. A participant from one group commented,

I (one member of the group) often used Facebook messenger to talk with my mom and sister to inform my location and activities and with my friends to catch up and know [learn about] the nearest attractive places and restaurants because he had been there. I used Facebook messenger because phone calls are expensive as I was on roaming whereas it is cost-effective and easy. (Group 6)

Eight groups of tourists mentioned that they used social media to coordinate with group members and share travel-related information, such as times and locations of group meetings and tourist destinations.Two groups commented:

Facebook messenger was more for a reason we [tour mates] communicated through when we need to share information [name of place/activity] or when we were trying to pass certain thoughts about the place. (Group G)

We sent our activities to do, time to meet in the ground floor for finalising which activity we will do first, and time to leave to hotel to our Facebook messenger group. (Group I)

It is worth noting that during the group trip, not all participants of a tour group were involved in trip-related tasks (e.g., information seeking, gathering and validating) using social media. The following quote by a group of participants illustrates the reason for not contributing to the tasks:

We both [daughter and mom] used to look for information because another member [grandmother] is old person and doesn’t know about social media. But she [grandmother] always share her opinion and choice to decide schedule [time to execute trip activities], taxi or metro rail, temple [places to visit], and foods. (Group 7)

The possible reasons for not participating in obtaining information on social media could be a dependency on other tour mates, being responsible for tasks unrelated to social media, lack of social media experience.

Roles played by social media during collaborative information seeking

This section discusses the role social media plays when a group of participants collaboratively seek information. We identified a number of roles that social media played during collaborative information seeking , including as a source of information, as a collaborative tool for the tour group, and as a way for travel mates to communicate within and outside of their group (Table 4).

Since tour groups re-planned the trip while travelling, the participants familiar with social media took responsibility for seeking, gathering and verifying information by scanning the experiences of, and making contact with, other experienced tourists on social media. Afterwards, they shared, synthesised and discussed the obtained information with their tour mates to narrow down the preferences and make final decisions. In this case, not all the members in a group participated in information seeking tasks because of their lack of knowledge and networks on social media, but they did provide valuable input (e.g., opinions and reasoning) on the gathered information during the group decision-making process. Likewise, some groups used social media for seeking information to resolve unforeseen circumstances (e.g., nearby visiting places of the participants’ current location) by asking for suggestions from a broader population. Information on social media is shared in real-time, guaranteeing that updates on local news and events posted there are the most recent and up-to-date. Thus, information on a destination acquired through social media aided tourists in re-planning of the on-going trip by ensuring a trouble-free group trip (or at least trouble-less). For instance, updates on tourists’ spots, (e.g., opening times and warnings for a local beach), helped tourists to re-schedule or alter their choice from the beach to another visiting place (e.g., indoor activities). Thus, collaborative information seeking enabled amateur members of a group to gather and acquire relevant travel information from expert members on social media to make a group decision. For intra-group collaboration, social media features such as free messaging and audio and video calling (helped collaborators to coordinate the entire group synchronously and asynchronously by sharing schedules, happenings atthe destination and personal opinions on travel activities.

Furthermore, during the trip, keeping in contact with other family members and friends on the other side of the world through social media helped participants to enjoy their journey with peace of mind. The following quotes demonstrate the role of social media in group travel:

We could imagine our trip activities in advance by watching images, videos and reading other people’s experiences on Facebook and blogs. It [social media] made easy to take decision instantly. We verified information as well. For our trip, social media played a role like another group member who is giving us information to make decisions throughout the tour. (Group C)

Social media was the number 1 instrument for us during travelling. When we needed to search [for] any information related to our trip, we used social media (WeChat and ctrip.com) at first to seek any information and help. We also got necessary information from other unknown tourists via social media. For example, during travelling in Melbourne, we found many useful information about places to stop to visit and restaurants from other tourists’ experiences on the way to Great Ocean drive. (Group B)

| Collaborative information seeking during the trip | Roles played by social media during collaborative information seeking | Features of social media contribute during collaborative information seeking |

|---|---|---|

| Seeking and sharing information | Social media plays a role as a source of information for participants while seeking tourism information. | Experiences, reviews, opinions, photos, and videos shared on blogs, Facebook, Instagram and WeChat |

| Synthesising information | Social media also works as diverse sources of information to come up with a new idea or plan. | Suggestions and opinions posted on blogs, FB travel groups and pages, and WeChat. |

| Making alterations | Social media provides a common communication platform for teammates to share their opinions while remotely located. | Group communication through Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, and WeChat. |

| Coordinating the group | Social media works as a collaborative tool for group communication. | Group communication by Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, and WeChat |

| Making on-site, trip-related decisions | Social media acts as an information source during the group discussion. | Reviews and ratings provided on google maps, and Facebook groups and pages. |

| Solving conflicts of preferences between group members | Social media facilitates a common media of communication for tour mates in sharing everyone’s perspectives | Group communication through Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, and WeChat |

Discussion

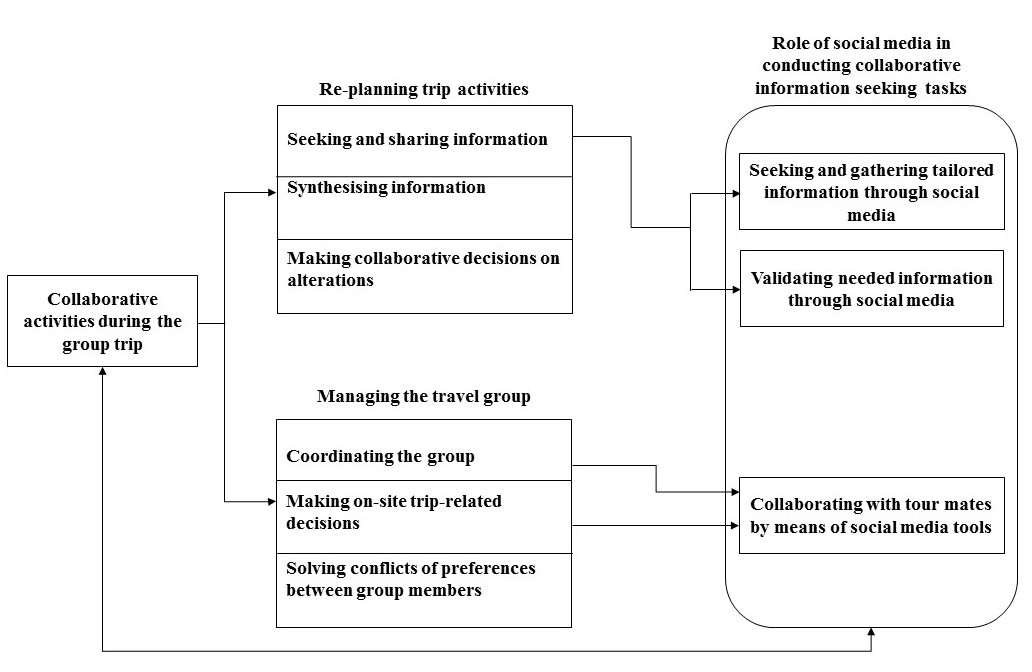

The qualitative approach (group interview) was used to explore the triggers of tourist collaborative information seeking and the circumstances of social media usage and their associated roles in supporting collaborative information seeking during travelling. We will now discuss what the findings tell us about tourism collaborative information seeking and interactions between group members, as well as intergroup collaboration on social media platforms. Based on the findings, we developed an empirical model (Figure 1) to illustrate collaborative information seeking behaviour and social media use of tourists travelling as a group.

Figure 1: Collaborative information seeking during travel: triggers and social media usage

Triggers of tourism collaborative information seeking behaviour

Collaboration helps team members solve problems and achieve their common goals; as such, it is important to identify triggers for intra-group collaboration in a tourism context to understand when tourists require collaboration and to define the aspects of their group behaviour. Our study established two key aspects of collaborative information seeking during group travelling. The first aspect was re-planning travel activities when tourists in groups had unexpected issues during the trip, including severe weather, illness, and disagreements over choices, events and activities. Tourists in a group were involved in information seeking and sharing, synthesising and making alterations to parts of the pre-planned travel activities. The second aspect was managing the travel group; tourists often collaborated with tour mates to coordinate the group, making on-site trip-related decisions (e.g., meals), and solving conflicts between members. For example, tour mates usually sent messages to the group forum regularly to decide when to leave the hotel and where to eat. The collaborative activities studied in this paper are different than the triggers identified in Tan and Goh's (2015a) study. We found a set of triggers that initiate collaborative activities between members of the tour group, while Tan and Goh presented triggers that initiate collaboration with non-group members by an individual tourist.

Intra-group collaboration

During the trip, tourists needed to work together for various travel purposes ranging from information seeking to make on-site group decisions. Moreover, a group was often physically co-located at that time. Therefore, the common and most convenient way to collaborate when seeking opinions and making collaborative decisions was face-to-face interaction. In the travel group, the methods of collaboration were chosen based on the situations and convenience of tourists. For example, tourists employed face-to-face interaction when they had to solve disputes on prospective travel activities and finalise decisions instantly. Also, face-to-face group interaction helped them to gauge satisfying decisions by observing every member’s facial expression. Another channel for intragroup communication was using social media tools (e.g., Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, and WeChat) to seek and share tourism information (e.g., background of local attractions, reviews, images and videos of scenic views, spots, temples, architectures, and museums) to do research on the potential changes of travel activities. A previous study (Mohammad Arif, Du and Lee, 2012) found that tourists collaborated with both co-located and remotely located people by phone calls, e-mails, instant messaging, face-to-face meetings and web inquiries during the travel planning stage. A more recent study by Ho, Lin, Yuan, Chen and Alvares (2016) also discovered that tourists communicated with their travel mates synchronously or asynchronously through voice calls, e-mails, Web inquiries, and social media tools for information searching during travel planning. However, our findings are different from the results of these studies in that we identified that the choice of methods for intragroup collaboration depended on the urgency of information needs and convenience of tourists, whereas previous studies were conducted during the travel planning phase and determined methods for collaboration only. Our results provide insights into the use of social media as an information searching and intragroup collaboration platform, which will encourage collaborative information seeking tool developers to integrate social media into their systems.

Collaboration through social media during group travelling

The flow of information is essential for the successful completion of collaborative activities (Mohammad Arif, et al., 2015; Spence, Reddy and Hall, 2005). However, this does not always happen in practice and requires collaboration with others to find the information needed to accomplish tasks. We identified that tour groups utilised social media to continue the flow of information during information seeking for re-scheduling travel activities. For example, team members deciding on a travel activity might require more information than they previously thought. In such a situation, technologically expert teammates (frequent social media users) performed information seeking, gathering, and validating through social media and then shared this information with the group to synthesise, assess and make decisions. Specifically, skilled collaborators read experiences of and interacted with other tourists on social media to bring a diverse range of ideas and knowledge, allowing them to obtain authentic and specific information to make a group decision quickly.

Because of the experiential nature of tourism information, potential tourists often look for the experiences of other tourists (non-travel group members) to help make informed decisions. Our study confirmed that a group of tourists preferred to rely on other experienced tourists’ opinions and knowledge on various social media platforms to re-plan or alter on-site activities. In this situation, they sought information from other social media users to learn, gather, and validate information for their own group’s trip re-planning. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Shah, Capra and Hansen (2017) who found that there are some situations in which both social ties and collaborative ties are required to solve a common problem. Our study added to the existing knowledge that social interactions assist in tourism collaborative information seeking.

This study has limitations. The focus of the research was to explore the triggers of a tourists’ group’s collaborative information seeking, their use of social media, and the role of social media during these activities. We did not investigate the effects of different sizes and types of travel groups (e.g., family or friends group) on tourists’ collaborative information seeking, which would be worthwhile for future endeavour.

Conclusion

Given the increasingly important role of social media in various domains such as education, healthcare, entertainment, and tourism, it is important that we develop an understanding of its use in collaborative information seeking during the group travel. The results highlight that, though the face-to-face meeting was the most commonly utilised means for intra-group collaboration when travelling, tourists often employed social media for various group activities. Re-planning group trip activities involved information seeking and sharing, during which tourists individually found, gathered and evaluated a wide range of travel information, (e.g., the background of attractions and weather, reviews on restaurants, transportation, security, and festivals) through social media and shared this information with the team. Social media served as sources of information, collaborative tools for the team, and a way to keep in contact with family and friends back home.

Earlier studies have revealed that an individual tourist interacts with inter-group and intra-group people to satisfy his or her information needs during travelling (Tan and Goh, 2015a). Tourists collaborate with their tour mates for gathering and sharing information verification, sharing knowledge and experience, and updating information (Fardous, et al., 2017; Mohammad Arif and Du, 2012). There is limited research on the triggers of tourists’ collaborative information seeking behaviour during the trip. Our study depicted triggers that lead to collaboration associated with the re-planning of the trip and managing the whole team while travelling. This finding on intra-group collaboration provides new insight on why groups of tourists need to work together while travelling together. It also adds to the existing knowledge of tourism collaborative information seeking by examining social media usage as support for intra-group collaboration in such circumstances.

About the authors

Jannatul Fardous is currently a PhD student at School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, University of South Australia, Australia. Her research is on investigating social media users’ collaborative information seeking behaviour during group trip planning and the execution of travelling. Earlier, she completed a master of Computer Science and Engineering and a bachelor in Computer Engineering from University of New South Wales, Australia and American International University-Bangladesh, respectively. She can be contacted at jannatul.fardous@mymail.unisa.edu.au.

Jia Tina Du (corresponding author), PhD, is senior lecturer in information studies in the School of Information Technology and Mathematical Sciences, University of South Australia. Tina is also an Australian Research Council (ARC) DECRA Fellow. Her research interests lie in basic, applied, industry and interdisciplinary studies in library and information science, and information management, including theories, models and experiments related to human information behaviour, Web search, and interactive and cognitive information retrieval. She can be contacted at Tina.Du@unisa.edu.au

Preben Hansen is a Docent, Associate Professor in Human-Computer Interaction at Stockholm University, Department of Computer and Systems Sciences. He is head of the Design and Collaborative Technologies Research Group, and is currently a Research Fellow at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His research area is in the intersection of interaction and human computer interaction and interaction design and (collaborative) information searching with a human-centred focus in behaviour, design and learning.

References

- Austin, L., Fisher Liu, B. & Jin, Y. (2012). How audiences seek out crisis information: exploring the social-mediated crisis communication model. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(2), 188–207.

- Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Cheverst, K., Davies, N., Mitchell, K. & Friday, A. (2000). Experiences of developing and deploying a context-aware tourist guide: the GUIDE project. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (pp. 20–31). New York, NY: ACM.

- Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C. & Buultjens, J. (2009). The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(8), 743–764.

- Decrop, A. (2005). Group processes in vacation decision-making. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 18(3), 23–36.

- Fardous, J., Du, J.T., Choo, K.-K. R., Huang, S. & Hansen, P. (2017). Exploring collaborative information search behavior of mobile social media users in trip planning. In iConference 2017 Proceedings (pp. 435–444). Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois. Retrieved from https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/handle/2142/96754

- Fotis, J., Buhalis, D. & Rossides, N. (2012). Social media use and impact during the holiday travel planning process. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, 2012, Proceedings of the International Conference in Helsingborg, Sweden, January 25–27, 2012 (pp. 13–24). Vienna; New York, NY: Springer

- Gauducheau, N. (2015). An exploratory study of the information-seeking activities of adolescents in a discussion forum. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(1), 43–55.

- Hamid, S., Bukhari, S., Ravana, S. D., Norman, A. A. & Ijab, M. T. (2016). Role of social media in information-seeking behaviour of international students: a systematic literature review. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 68(5), 643–666.

- Hansen, P. & Järvelin, K. (2005). Collaborative information retrieval in an information-intensive domain. Information Processing & Management, 41(5), 1101–1119.

- Harrigan, P., Evers, U., Miles, M. & Daly, T. (2017). Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tourism Management, 59(Supplement C), 597–609.

- Ho, C.-I., Lin, Y.-C., Yuan, Y.-L., Chen, M.-C. & Alvares, C. (2016). Pre-trip tourism information search by smartphones and use of alternative information channels: a conceptual model. Cogent Social Sciences, 2(1). Retrieved from https://www.cogentoa.com/article/10.1080/23311886.2015.1136100 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2OUYr9w)

- Hsieh, H.-F. & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

- Hudson, S. & Thal, K. (2013). The impact of social media on the consumer decision process: implications for tourism marketing. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1/2), 156–160.

- Kim, K.-S., Sin, S.-C. J. & He, Y. (2013). Information seeking through social media: impact of user characteristics on social media use. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 50(1), 1–4. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/meet.14505001155

- Kim, S.-E., Lee, K. Y., Shin, S. I. & Yang, S.-B. (2017). Effects of tourism information quality in social media on destination image formation: the case of Sina Weibo. Information & Management, 54(6), 687–702.

- Kvale, S. & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lazar, J., Feng, J. H. & Hochheiser, H. (2017). Surveys. In Jonathan Lazar, Jinjuan Feng and Harry Hochheiser, Research methods in human computer interaction (pp. 105–133). Cambridge, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Leung, D., Law, R., van Hoof, H. & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media in tourism and hospitality: a literature review. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1/2), 3–22.

- Mammadov, R. (2012). The importance of transportation in tourism sector. In 7th Silk Road International Conference; Challenges and Opportunities of Sustainable Economic Development in Eurasian Countries. Tbilisi-Batumi, Georgia: Black Sea University.

- Marchionini, G. (1989). Information-seeking strategies of novices using a full-text electronic encyclopedia. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 40(1), 54–66.

- Mohammad Arif, A. S., Du, J. T. & Lee, I. (2012). Towards a model of collaborative information retrieval in tourism. In Proceedings of the 4th Information Interaction in Context Symposium, Nijmegen, The Netherlands — August 21 - 24, 2012, (pp. 258–261). New York, NY: ACM.

- Mohammad Arif, A.S., Du, J.T. & Lee, I. (2015). Understanding tourists’ collaborative information retrieval behavior to inform design. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(11), 2285–2303.

- Morris, M. (2008). A survey of collaborative web search practices. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal, Québec, Canada — April 22-27, 2006, (pp. 1657–1660). New York, NY: ACM.

- Morris, M. R., Teevan, J. & Panovich, K. (2010). A comparison of information seeking using search engines and social networks. In Proceedings of ICWSM, 2010, Washington, DC, USA, May 2010. (pp. 23–26). Palo Alto, CA: AAAI Press. Retrieved from https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM10/paper/viewPaper/1518 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2MMzvhr)

- Neuman, W. L. (2011). Social research methods: qualitative and quantitative approaches. (7th ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

- Parra-Lopez, E., Gutierrez-Tano, D., Diaz-Armas, R. J. & Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2016). Travellers 2.0: motivation, opportunity and ability to use social media. In M. Sigala, E. Christou & U. Gretzel (Eds.), Social media in travel, tourism and hospitality: theory, practice and cases (pp. 171–187). Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Reddy, M. C. & Spence, P. R. (2008). Collaborative information seeking: a field study of a multidisciplinary patient care team. Information Processing & Management, 44(1), 242–255.

- Rezdy. (2016). Travel statistics for tour operators. Retrieved from https://www.rezdy.com/resource/travel-statistics-for-tour-operators/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2MEs4ZC).

- Savolainen, R. (2017). Information need as trigger and driver of information seeking: a conceptual analysis. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 69(1), 2–21.

- Schänzel, H. A. & Yeoman, I. (2015). Trends in family tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(2), 141–147.

- Schroeder, A. & Pennington-Gray, L. (2015). The role of social media in international tourist’s decision making. Journal of Travel Research, 54(5), 584–595.

- Shah, C. (2014). Collaborative information seeking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(2), 215–236.

- Shah, C. & Marchionini, G. (2010). Awareness in collaborative information seeking. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(10), 1970–1986.

- Shah, C., Capra, R. & Hansen, P. (2017). Research agenda for social and collaborative information seeking. Library & Information Science Research, 39(2), 140–146.

- Shaw, R. J. & Johnson, C. M. (2011). Health information seeking and social media use on the internet among people with diabetes. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics, 3(1), 9. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23569602 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2yNWK2F

- Simms, A. (2012). Online user-generated content for travel planning-different for different kinds of trips? E-Review of Tourism Research, 10(3), 76–85. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2KmRF7V

- Spence, P. R., Reddy, M. C. & Hall, R. (2005). A survey of collaborative information seeking practices of academic researchers. In GROUP ’05 Proceedings of the 2005 international ACM SIGGROUP conference on Supporting group work, Sanibel Island, FL (pp. 85–88). New York, NY: ACM.

- Sterling, G. (2016, April 4). Nearly 80 percent of social media time now spent on mobile devices. [Web log post] Retrieved from http://marketingland.com/facebook-usage-accounts-1-5-minutes-spent-mobile-171561 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2GNbZxj)

- Tan, E. & Goh, D. (2015a). A study of social interaction during mobile information seeking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(10), 2031–2044.

- Virtue, R. (2014, April 30). Is social media the future for the tourism industry? ABC Central West NSW. Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2014/04/30/3995174.htm

- Volo, S. (2010). Bloggers’ reported tourist experiences: their utility as a tourism data source and their effect on prospective tourists. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 16(4), 297–311.

- Wang, Yu, Q. & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2002). Defining the virtual tourist community: implications for tourism marketing. Tourism Management, 23(4), 407–417.

- Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249–270.

- Xiang, Z. & Gretzel, U. (2010). Role of social media in online travel information search. Tourism Management, 31(2), 179–188.

- Xiang, Z., Wang, D., O’Leary, J. T. & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2015). Adapting to the Internet: trends in travelers’ use of the web for trip planning. Journal of Travel Research, 54(4), 511–527.

- Zeng, B. & Gerritsen, R. (2014). What do we know about social media in tourism? A review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10(1)ß, 27–36.