Research together: exploring students' collaborative information behaviour in group work settings

Parisa Khatamian Far

Introduction: While higher education institutions place considerable emphasis on developing students' teamwork skills by designing group projects, the literature shows that employers are still not satisfied with graduates' collaborative work skills. Hence, this research aimed to explore how students collaboratively identify the information need, gather and exchange information and use information to complete their group assignments.

Method: This qualitative research used Straussian grounded theory. Ten semi-structured focus group interviews were held, and participants were asked to discuss their experience of undertaking group assignments.

Analysis: Data analysis was based on constant comparative method to analyse and then categorise research data to identify emergent types of students' information behaviour in university group context.

Results: Dividing the task is a common strategy considering the nature of the assignment which leads to individual information seeking. Those who valued shared awareness of the group's overall progress maintained their active communication throughout the process which was highly beneficial when they integrated separate parts to prepare a coherent assignment.

Conclusion: This research contributes to understanding of students' collaborative information behaviour in terms of activities, strategies and difficulties they face and also provides better insights into how to reorient group assignments to enhance the academic collaborative environment.

Introduction

Researchers and scholars have examined several aspects of information seeking behaviour over many decades which has led to the development of various models and conceptual frameworks to describe the concepts representing this phenomenon (Fisher, Erdelez and McKechnie, 2005). Although these models and conceptual frameworks have been formed following different approaches, they all have individualistic perspective. Wilson (1999) raised an important question: 'to what extent are the different models complete, or complete representations of the reality they seek to model? (p. 267), highlighting how the collaborative and social aspect of information seeking behaviour had been overlooked to that point in time.

Thus, some researchers have devoted more attention to the importance of the collaborative aspect of information behaviour, challenging the individualistic perspective by exploring people's behaviour when they collaboratively seek, retrieve and use information. In this regard, collaborative information behaviour has been proposed as an umbrella term to denote the collaborative aspects of information seeking, retrieval and use and is defined as,

the totality of behaviour exhibited when people work together to (a) understand and formulate the information need through the help of shared representations; (b) seek the needed information through a cyclical process of searching, retrieving, and sharing; and (c) put the found information to use (Karunakaran, Reddy and Spence, 2013, p. 2438).

Several studies have been carried out to examine collaborative information behaviour in different domains including the military (e.g., Sonnenwald and Pierce, 2000), engineering (e.g., Bruce et al., 2003), health (e.g., Reddy and Dourish, 2002) and education (e.g., Hyldegård, 2006) which has led to the development of some models and frameworks (e.g., Karunakaran, et al.; Reddy and Jansen, 2008; Shah, 2008; Yue and He, 2010) A number of workshops have also been run with different aims such as discussing current conceptions of collaborative information seeking, issues in designing collaborative search tools, and evaluation of collaborative information retrieval and seeking (Azzopardi, Pickens, Sakai, Soulier and Tamine, 2016; Azzopardi, Pickens, Shah, Soulier and Tamine, 2018; Shah, Capra and Hansen, 2015; Shah, Hansen and Capra, 2012). However, scholars believe that this area of research is still young and there are many challenges including a lack of theories to understand the stages as well as individual and collaborative activities in the process (Tao and Tombros, 2013); suitable data collection and analysis methods and evaluation frameworks (Shah, Capra and Hansen, 2015). These underline the need to conduct more research studies.

Specific to the academic environment, there has been an increasing expectation that university graduates will be equipped with the skills required to work collaboratively with others; hence, higher education institutions put emphasis on developing group work skills and the teamwork abilities of students by assigning group work projects. However, the findings of research reports demonstrate that employers are still complaining that newly-hired graduates lack adequate skills to work collaboratively with others (e.g., Cooley, Burns and Cumming, 2015; Oliver, Whelan, Hunt and Hammer, 2011). Shah (2014) explains that in situations with instructor-enforced class groups, people are compelled to work collaboratively with each other which may start with cooperative actions where they have to comply with a set of guidelines and rules working with others. He was also of the opinion that these cooperative situations may result in collaboration if the group members actively engage in this process and work together towards attaining a shared goal. However, he believed that unsuccessful collaboration is predictable if the participants do not trust each other or if the authority and responsibilities have not been delegated properly. Therefore, several factors can play a part in influencing collaborative information behaviour activities of students in the context of group work. Hence, gaining a conceptual understanding of how students collaboratively seek, exchange, evaluate and use information in a group work setting to accomplish a shared goal is of great importance in learning environments.

This paper will present early findings of a qualitative study which used focus groups to investigate students' collaborative information behaviour over the duration of group tasks in terms of activities, strategies and difficulties they faced in the process.

Literature review

One of the early studies in the academic environment was Limberg's (1999) work. This research was not originally carried out as a study examining collaborative information behaviour, but nonetheless has provided deeper understanding of information behaviour practices in group-based settings. She examined the information behaviour seeking practices of five groups of students (18-19 years old) during a group assignment. The findings demonstrated that students' attitudes towards group work had an impact on their approach toward information behaviour activities. Group members with a holistic approach (we-orientation) include those students with positive attitude towards group work who understand the value of working with others to reach a shared goal, communicated and exchanged information more effectively and continuously informed each other of their outcomes. Groups with an atomistic approach to group work (I-orientation), including those who divided the assignment into different parts, did not collaboratively find, assess, and use information.

More recently, researchers have explicitly focused on studying collaborative information behaviour in an academic field and few studies have been conducted based on the traditional frameworks and models of information behaviour examining their applicability in group-based learning environment. For instance, Hyldegård (2006) is one of those first researchers who explored collaborative information behaviour in an academic setting and used Kuhlthau's (1991) information search process model as her research conceptual framework. The findings revealed some similarities between the Kuhlthau's model and the behaviour of the individual group members; while, many differences were also found which turned out to be related to group work, task, and personal factors. Likewise, Shah and González-Ibáñez (2010) took Kuhlthau's model and mapped it to a collaborative information seeking setting to show that the group members' behaviour could be shifted between different stages of the information search process model due to interaction, communication and exchanging information between students. Ndumbaro and Mutula (2019) examined students' collaborative information behaviour in comparison with Wilson's (1996) model of information behaviour. The results of this study revealed that Wilson's model is partially applicable for understanding students' information behaviour in the group context. In particular, person(s) in context and active and passive information seeking are the aspects of the model which could be relevant to student's collaborative information behaviour. In overall, we can infer that comparing group information behaviour with solitary models can provide researchers with interesting insights; however, they lack the potential to describe the collaborative practices of team members and their interactions.

Some researchers have concentrated their efforts on students' collaborative search activities and examining the effectiveness of collaborative search tools (e.g., González-Ibáñez, Haseki and Shah, 2013; Wu and Yu, 2015). Leeder and Shah (2016) conducted an empirical case study to investigate the strategies that students use and the obstacles they encounter while working in collaborative information seeking contexts over the course of the group project. Data analysis showed that students believed that using collaborative tools such as Google Docs can provide substantial benefits for the group work; in particular creating shared representation. The major obstacles that they mentioned were also unequal contribution and procrastination.

Shah and Leeder (2016) carried out another research study to explore collaborative work among graduate students using C5 model of collaboration (Shah, 2008). Managing scope was identified as the most common challenge in student groups. In addition, work-style orientation and choices of methods of communication were considered as influential factors to the success of the group project. The results of this study also showed that coordination and cooperation were much more important during the initial stage while, collaboration became more important at the end.

Saleh's (2012) research provided profound insights into how collaborative information behaviour is dynamically shaped by the characteristics of the learning task. He found a strong relationship between learning task stages, task complexity, and collaborative information behaviour. The study highlighted the need for groups to construct and share a collaborative situation awareness in order to maintain and regulate their activities in information seeking and use. This shared awareness was enabled by students' interactions in their group meetings or their use of collaborative software tools for information sharing.

Wu, Liang, and Yu's (2018) research emphasised users' learning during collaborative information search process. Their results showed that students' learning during this process included knowledge reconstruction, tuning, and assimilation. Findings also revealed that collaborative search could enhance students' learning experiences and would have positive impact on gaining new knowledge and developing students' research and communication skills. The researchers conclude that the most common strategy of collaboration in students' group work is division of labour and three crucial success factors are strong team leader who had a better understanding of the research topic, clear and fair division of labour, and active communication among team members.

In summary, there are several studies on group work in educational context and recently researchers devoted more attention to students' collaborative information behaviour during this process. According to Hertzum and Hansen (2018), the most common methods of data collection in these studies are laboratory experiments, and surveys. Laboratory experiments are limited to quite short sessions and surveys can provide snapshots of students' collaborative research behaviour; neither generate rich qualitative data. Hence, this work has addressed this limitation by conducting a qualitative study which provides access to participants' description and explanations of their collaborative and individual information behaviour activities.

Research design

This project adopted qualitative research approach to allow the researcher to 'study things in their natural setting, attempting to make sense of, or interpret phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them' (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005, p. 3). Thus, it provides deep insight, rich description, and detailed understanding of how students find, seek, and use information collaboratively to complete their group assignments. Given these considerations, Straussian grounded theory has been selected as a research methodology. Grounded theory is an inductive methodology that enables the researcher to examine the topics and behaviour from many different angles which can provide detailed description and comprehensive explanations (Corbin and Strauss, 2015).

Focus groups were employed as the method of data collection. These are particularly suited for obtaining several perspectives about the same topic and gaining deeper insights (Gibbs, 1997) and provide an opportunity for researchers to engage with participants and probe when responses need more explanation (Barbour, 2008). In addition, social interaction between participants provides insight and data that cannot be obtained via other methods as it enables respondents to question each other and re-evaluate their own understandings of their specific experiences (Gibbs, 1997).

Study population and research participants

Students at Edith Cowan University who were about to complete and submit their group assignments or had done so in the previous twelve months as part of their university degrees across any number of discipline areas were eligible to take part in focus group sessions. The guided questions probed students' information behaviour activities (encompassing sensemaking and identifying information need, seeking information and using information during the group assignment) to find out the extent to which these activities had been performed individually or collaboratively. Some relevant follow-up questions were asked during the focus groups to further explore their insights and experiences.

The invitation to participate in the research was published on the university's student Intranet during semester 2, 2017 and semester 1, 2018. In addition to a brief and vivid description of research, a short video was also provided. Participants were accepted in the order the researcher received their e-mails and their eligibility to take part in research was confirmed before they were sent an invitation to attend a focus group.

In total, ten focus group sessions with thirty-nine participants were held and the sessions took approximately two hours with three to four participants in each. Participants' demographic information is found in Table 1.

| Demographic variables | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13 | 33.3 |

| Female | 26 | 66.7 |

| Age range | ||

| 18-30 year | 29 | 74.3 |

| 31-40 year | 4 | 10.3 |

| 41-50 year | 4 | 10.3 |

| 50 and older | 2 | 5.1 |

| Domestic or international | ||

| Domestic | 25 | 64.1 |

| International | 14 | 35.9 |

| Degree | ||

| Bachelor | 28 | 71.8 |

| Master | 8 | 20.5 |

| Graduate Diploma | 3 | 7.7 |

| School | ||

| Business | 15 | 38.4 |

| Education | 6 | 15.4 |

| Medical & health sciences | 6 | 15.4 |

| Arts & humanities | 5 | 12.8 |

| Engineering | 3 | 7.7 |

| Science | 3 | 7.7 |

| Nursing & midwifery | 1 | 2.6 |

A majority of participants described their experience of working in groups formed by self-selection method with four to five members which is commonly reported as an ideal group size (Chiriac and Granström, 2012; Kriflik and Mullan, 2007). Participants' group projects varied in terms of complexity and creativity ranging from writing research essays, doing case studies and reviewing an article to developing a product such as software, along with creative tasks including art piece, performance and music.

Data analysis

The analysis was conducted by following the coding procedures of Corbin and Strauss's (2015) grounded theory. The discussions in the focus groups were audio recorded and then transcribed in full. The researcher began the analysis based on the transcriptions by breaking down the data into manageable pieces, reflecting upon that data in memos and conceptualising it. At this stage the emerged concepts were undeveloped and unverified; employing constant comparative method enabled the researcher to elaborate on the identified concepts in terms of their properties and dimensions which led to a better understanding of the concepts. During the next phase of coding, the researcher brought the process of students' collaborative information behaviour into the analysis by focusing on identifying the conditions that shaped the participants' experiences and action-interaction taken to respond to the changes in conditions. The final stage synthesised and integrated the relationships among categories that explained how and why students engaged in collaborative or individual information practices over the course of completing their group task.

Results and discussion

Data analysis revealed that students complete their group assignment in three stages. The initial stage (phase one) is when students start to make sense of the group task, become familiar with other group members and assign roles or specific tasks to each member. At the mid-point stage (phase two), they search for relevant information to complete their assigned subtasks. Finally, at the completion stage (phase three), they put group members' work together to integrate separate parts and create a cohesive assignment. In the following section, the students' information behaviour and their collaborative activities will be explained in detail for each phase.

Types of collaborative activities and information behaviour in phase one

Ice breaker activity

This is the first activity after students form their group. The majority of participants asserted that they had seen the group members in different classes but they did not know them personally. Therefore, they usually start their first meeting by talking about themselves, their prior experience of undertaking group assignments, their skills and their prior knowledge about the topic.

This kind of activity would help students to get to know each other better and feel more comfortable working in that group. They could identify their key strengths in regard to the assignment and try to use group members' qualities and abilities in the best way in order to achieve the best results. Therefore, they could feel particularly pleased with the group members at the beginning and believe that every member of the group could contribute in some way to completing the group task successfully.

Discussing expectations and setting group norms

Following the previous activity, some groups directed the conversation towards discussing expectations such as quality and standards, referencing and more importantly, getting a high mark. They also tried to establish some rules and a set of principles for the group and everyone agreed to conform to the accepted rules. Participants asserted that discussing everyone's expectations and reaching an agreement on group norms at the beginning helped them to feel more united in terms of actions they took towards achieving their common goal:

We started the first part ice-breaking kind of thing just familiarising ourselves with each other then we asked to create routine norms which was basically a set of expectations that we all have to agree on. For instance, what mark we want to get, what we expect from one another, kind of set up from the beginning the expectations that we all had to comply. We all agreed on everything and probably from the beginning I feel very like belonging to them and very comfortable with them. (Participant 1; 2nd focus group)

However, some participants mentioned that they did not pay serious attention to discussing their expectations for the group work nor members' aspirations to gain a clear understanding of their desire to achieve the team's shared goal. When the submission deadline became closer, these respondents recognised that some group members did not intend to make equal contributions and their input was below standard. The undesirable consequence was others in the group taking over those members' subtasks and dealing with more workload to get a good mark:

he left that section blank. While it was an important section he said, 'no that is Ok I've done it before in another assignment I get at least 50 marks in total anyway so it is fine'. I said 'oh OK' so I guess when he backed off and let me write his part for him that was more relieving because at least the standard was similar across the work. (Participant 3; 2nd focus group)

Brainstorming

After students had become familiar with other group members, shared their experiences, discussed their expectations and established some norms for the group work, they continued their collaborative work by brainstorming ideas about the topic and clarifying the requirements of the assignment. However, the type of task had significant impact on group brainstorming. Some students described their group assignment as a list of subtopics and they started to divide those among themselves based on their interest or just randomly during the first meeting. Their tasks can be categorised as fully-assigned tasks, defined as 'those that have both the main topic and aspects of the topic imposed on the user' (Bilal, 2002, p 1171). Hence, they were not required to search for background information, develop ideas, discuss their thoughts and come up with the main topic and subtopics:

So in the assessment sheet there was like dot points the things that we had to cover and I was just lucky that it was, like, even number so it could be divided by four, so we just all got two dot points each and we just, like, 'ok go away research them' and then we'll come back and then we kind of put it all together. (Participant 4; 4th focus group)

so our teacher, like, gave us a handout with all different tasks and was, like, writing our names next to it and that person would do that task. So, we decided that and the way we approached that was literally just like writing the name down in order, so, it was just, you got what were given. (Participant 3; 9th focus group)

In contrast, some of the participants maintained that they were assigned a general subject and they had to do some initial background research to come up with ideas. These types of tasks are considered as semi-assigned tasks that 'have only the main topic imposed on the user and the user can choose an aspect of the topic that interests him or her to pursue' (Bilal, 2002, p. 1171):

we were required to create a report on specific problem in public health … we agreed to go away and think about topics and pitch them to each other as one sentence pitch of whatever topic we came up with and then we would discuss them and agreed upon them in the next class … we eventually chose to look at domestic violence in sport. (Participant 2; 5th focus group)

According to the above participant quotations, it can be seen how the nature of the group assignments can have an impact on identifying and clarifying the information need collaboratively as well as generating a shared understanding of the retrieved information.

Dividing the work and assigning specific roles

When students were assigned pre-selected subtopics by the lecturer, they would divide the subtopics among themselves without doing any background research. However, when students were given a general subject, they had to do some initial research and come up with new ideas and collaboratively select the topic, then divide the subtopics among themselves based on their interest or strengths. In these cases, some participants did the background research and brainstorming together to collaboratively make sense of the topic. Conducting background research to gain more information about the topic and get a better understanding of the task can generate interest in those group members who might not have sufficient knowledge about the subject. In addition, it could help match individual group members' assigned roles or subtasks with their perceived abilities, knowledge and skills. It then potentially increased the members' intrinsic motivation to the group task as they developed a clear and greater understanding of the group's common objective and their role in the group:

We would all be researching you know initially what the topic we were interested in doing and then we had decided on our topic. Then the other students found a very good reference which mentioned sort of five key areas that Gough Whitlam had been influential in so from that we broke it down. One was international affairs and international students decided to do that and Aboriginal Indigenous studies area there was an Aboriginal lady who decided to do that and the arts there was a WAAPA student, so she did that one and I did education and I found that interesting. (Participant 3; 8th focus group)

On the other hand, some of the participants mentioned that they were the only one who did the initial research and the other group members did not pay serious attention to the importance of searching for general information to extend their understanding of the task, develop ideas, select a topic together and actually start to work on the group assignment to be able to successfully complete it before the due date:

I made sure I put lots of points on the discussion board and I tried to attend every meeting and I tried to make sure we [were] all discussing the same thing but it seemed like no one wanted to do the research until a few weeks before or the last week it was due. So you know we were all just mostly mopping around during the first meetings just getting to know each other… it was more just like delaying, time wasting time kind of thing. (Participant 3; 4th focus group)

[My group members] told me to choose the company myself but I did not really want to do this because this is a group assignment a group effort… I wanted everyone worked together choose the company share the ideas and thoughts and come with solutions. (Participant 4; 1st focus group)

Furthermore, some of the participants reported that one of the group members who strongly believed in their abilities, experience and background knowledge about the subject, enforced their views on selecting the topic and assigning group members specific tasks. They noted that some of their group members were happy with this situation as they acted like followers in the group and they were fully satisfied to be told what to do as they needed to be led. Nonetheless, this kind of attitude and mindset could raise tension in a group and have a damaging impact on effective collaboration. For instance, one of the participants called herself an opinionated person and made the following comment in regard to selecting the topic and dividing the task:

I decided what we were going to do. My partner was more than happy with it, the guy [the third member of the group] kept disagreeing but we kept saying this is what we are going to do. We told him what he needed to do; he did not do it; we chased him; he did it; he sent it; we sent it back [and] corrected it. (Participant 1; 6th focus group)

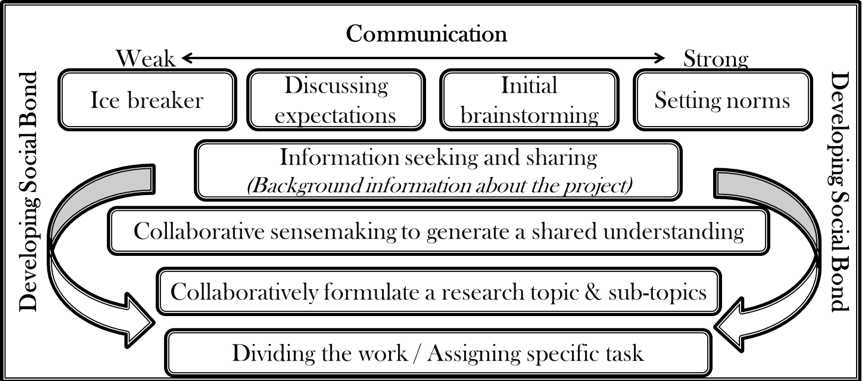

Considering the above points, the desired process of collaborative activities and students' information behaviour during the planning stage can be demonstrated in a diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Students' collaborative activities and information behaviour during phase one (initial/planning stage)

Student groups are usually considered as newly-formed groups in which members do not have prior work experience with one another. Thus, they should start their group work by discussing each other's previous experience of working in groups, specifically particular expertise, and different skills that they have and can offer to the group to be able to work together in a coordinated way to accomplish their common goal. They should devote close attention to discussing group expectations to resolve the issues at the beginning and set specific rules to enable efficient group work. Developing a shared understanding of the task is of paramount importance at this stage enabling students to effectively distribute the workload. Towards this end, all the group members should conduct brief information seeking to gain more knowledge about the subject and share their ideas with the group to make sense of the retrieved information together and collectively formulate the shared information need.

The findings showed that some groups searched for information together and discussed it simultaneously during the first meetings to come up with their research topic; while some performed information seeking individually, then shared and discussed their ideas and retrieved information further in group meetings. However, two important factors, including the type of group task and students' attitude towards group work (dominant members versus follower members), play a pivotal role in this process. Communication is an integral element in collaborative group projects (Shah, 2008). The majority of students claimed that they had frequent communication during the planning stage including face-to-face group meetings as well as online communication to share resources and ideas and come to a collective decision about each member's responsibility. However, maintaining strong communication over the course of the group project could have a positive impact on their successful collaboration and satisfaction.

Types of collaborative activities and information behaviour in phase two

Searching for information individually

One of the important activities in the second phase of completing a group assignment is seeking and searching for information. Participants maintained that they were involved in both individual and collective information seeking in phase one to gain a shared understanding of their task, but searching for information had been conducted individually after dividing the work given that each group member had specific subtopics to work on. They believed that when they got together to search databases, they were easily distracted by discussing other topics:

we started looking for information and they were concentrating on that but eventually there were some distractions, like, there was upcoming cricket match and they started talking about it and their interest went out of the project… that distraction eventually annoyed me and then I decided to come back home. (Participant 4; 2nd focus group)

Some also believed that searching for information along with other group members would be a time-consuming process. They maintained that considering the strict deadline for submitting the assignment, searching for information individually then coming back and integrating separate parts would be the easiest strategy to collaborate:

you know, like, sitting and searching it is not really – much of it does not need group participation to just search for an article, like, we can do that on our own and coming back and compare, that was the idea … looking at the time it will take, a lot, for both of us to go through so many articles together. It makes more sense to search individually, come up with an article that we found interesting and relevant to our topic. (Participant 4; 10th focus group)

However, those who also had the experience of searching for information collaboratively with other group members believed that they learned more and got a better understanding of the research topic and it also helped them to create an encouraging environment to work with the team members. This has been explicitly stated in the following quotation from the same participant who described her experience of conducting two different group assignments:

You understood the whole thing better and the work, you know, like, doing all the work alone is, you only have one view of it. When you just divide the work, every section has one person's view on it but when you did every bits together so the standard is better, you understand the material more and we also got a really good mark on that particular assignment but it took us so much time, like, a lot of time. (Participant 4; 10th focus group)

Sharing information

Sharing information is another activity during the mid-point stage that almost all the participants mentioned. Although they searched for information individually for their specific aspect, when they found useful, interesting and relevant information to the task, they shared it with the group via online communication technologies that they were using. One of the participants described the process of sharing information as an opportunity for creating unity in the group which could demonstrate that everyone was motivated towards achieving their shared goal despite working on their assigned subtasks:

It was the middle of our assignment, doing more research sharing ideas and then any time someone found a link to something very useful for any of us, whether it was for themselves or us [all], they would post it and it was not the process being ignored everyone would, you know, contribute more on that link and say, oh this is a good idea, this would be useful for your section, or this would be great for your section, so in that sense, everyone was doing very well with just sharing their thoughts and ideas and helping other people. So it was not just you got your section and do it and submit it before the deadline, it was everyone. (Participant 4; 1st focus group)

However, participants believed that this kind of contribution had not been made by all the group members: some were more active in sharing and exchanging information. More important, they could not even make sure that the group members had used the information they shared:

There were some people who sit back and listen to the share of ideas and used those ideas but not contributing. There were instances where I find really good reading and I would share that, but that was never reciprocated. (Participant 1; 9th focus group)

Sharing and exchanging information regarding the task is an important activity; however, the shared information by group members should be processed at the group level to be effectively used otherwise it would not influence the team's performance. Some of the participants indicated that their effort towards sharing information was quite useless because they found the information and assessed it individually and then shared it with the group but they were not able to achieve a consensus on using those pieces of information due to lack of detailed discussion about the exchanged information. On the other hand, those participants who had a positive experience maintained that when they found information relevant to the task, they would share it online and then they discussed it in group meetings to build a shared understanding. They thought that making sense of the new information could not be done online, which is consistent with the research results of Tao and Tombros (2013) showing limited use of shared information on chat tools as collaborators found it difficult and time-consuming to make sense of the shared information by themselves:

I found it [social media] useful for sharing references, passing on articles to each other but we went through the actual content in person. (Participant 1; 8th focus group).

Providing suggestion and feedback

One of the important activities during the mid-point stage of completing a group assignment is becoming aware of everyone's progress, reading each other's sections, and providing feedback to improve the whole content to be able to prepare a cohesive and consistent report or presentation. However, some of the participants indicated that they did not have any sort of communication during this stage: they worked on their own sections and few days before the presentation or submitting the final report they got together and went through the all the sections together. They were not happy with this process and believed that it was not a true collaboration:

we split it up. We kind of did our own thing and brought it together about half-an-hour before the presentation. That was a very different experience, so that was just do your own section and no real collaboration. (Participant 1; 1st focus group)

In this regard, participants also pointed out that when group members do not collaborate on reviewing each other's sections and making constructive comments to improve the project, each section has been written from one person's view or perspective and they called it one-person game. They stated that these people would rather receive instructions and leave the rest of the project to be finished by the leader than make a useful contribution towards their common objectives.

However, the participants who consistently gave each other feedback at different stages of the group project stated that they provided feedback and made comments on each other's sections usually during face-to-face meetings as well as through online communication channels:

face-face meetings and discussion board just like we say if it was good or bad, if it feels good or bad. If it was not good, we would say it need improvement, you need to go and find some more information, you are looking at the wrong part. If it was good, we would tell them what was good about it and give them more constructive feedback. (Participant 1; 2nd focus group)

Some participants also indicated that they used Google Docs as a shared platform to prepare their assignment which enabled them to have access to each other's sections and made it easier for them to provide brief and helpful comments and edit the content:

GoogleDocs I thought that was like an upgraded version of e-mailing because you all see the same assignment, little chat on the side. You can live chat each other, you can see people updating things and you can, like, tag each other for what each person had to do for each section, so it is pretty clear. You know if anyone has done anything and you could also see the history of the document. You can see if there is editing details, you could also edit other people's work and say, you know maybe in chat, where they go wrong. You can highlight things and maybe they could change it or reference it. You can edit references. (Participant 3; 4th focus group)

However, the majority of participants believed that giving feedback and working on each group member's part can be done easier during face-to-face meetings because they would obtain a better understanding of the discussion and it would be more effective compared to making comments online and receiving not useful feedback such as 'oh yeah it looks good'.

On the other hand, a few participants were of the opinion that if the group members are not prepared and have not read the material beforehand, running face-to-face meetings would be waste of time without reaching a conclusion or a solution:

Face-to-face meetings to me do not seem very productive because people get very distracted very easily and start talking about I want to see this movie I want to do that and you have to kind of trying and keep them back on track back on track back on track and if I come to a meeting face to face and I have ok this is a print out of what we have done so far then I will be like yeah I'll do that oh yeah that was on my computer I do not have that with me and so it allows them to make a lot of excuses about not having it there with them and that can become quite frustrating because you go into the face to face meetings looking to achieve something and come out saying OK so the only thing we achieve just we acknowledge the problem and we did not actually solve anything. (Participant 2; 5th focus group)

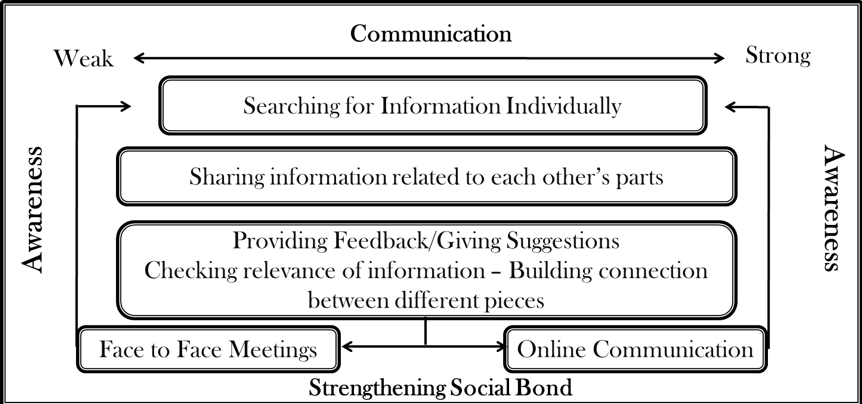

In the following diagram (Figure 2), students' information behaviour and their collaborative activities during the second phase of completing a group assignment are illustrated. Each member is responsible for seeking information and resources to carry out their task and they prefer it to do it individually. However, establishing effective and appropriate communication has a crucial role in this phase for maintaining active collaboration between group members and, more importantly, creating a shared awareness about the overall task progress and group members' current status. Ideally, the group would share new information and creative ideas, seek elaboration on exchanged information to assess its value and usefulness, and evaluate one another's sections in terms of relevance and consistency to enhance the quality and standard of the assignment.

Figure 2: Students' collaborative activities and information behaviour during phase two (mid-point stage)

Types of collaborative activities and information behaviour in phase three

Compiling information

The first activity in the last stage of completing a group assignment is compiling all the pieces of information and preparing a coherent report or presentation. Some of the participants pointed out that they did this part together. They arranged a meeting few days before submission to go through all the sections and making sure of consistency between the different parts. However, the majority of them were those whose final work was a presentation, so they had to get together to practice their presentation as well.

We both finished our own parts but then we got together, said, OK I think this could be improved. I think the font size could be improved, more pictures could be added here. We were just both on the same page so it worked and I just found it very easy. (Participant 1; 8th focus group)

On the other hand, those respondents whose assignment was a written report asserted that group members usually sent their sections to the person who held the leadership role to collate the information. They claimed that the group leader would do this by themselves or with the help of another group member. They had to send several e-mails to those who had not yet submitted their sections, they had to organise all the sections, put them together, check references, prepare the final draft, then submit the assignment. A serious problem came up when they recognised that the quality of the work sent by other members was poor, the information was not relevant to the subject, and the citations were incorrect. Thus, they had to spend a lot of time fixing it or re-writing those sections one night before submission:

I would just wait for his bits which he sent like maybe two days before submission. So when I got his bits, and I have seen this guy's work before and he has good grammar, but the bit he sent me oh my god, you know like, hard to go through his work because you can clearly tell those two parts had been written by like two different people so … it took me three hours to fix his work and, like, flesh it out properly in a way that it can be submitted but I have to do his work and the way he did it is, like, he gets our research article and just maybe cut paste like just a part of that article… (Participant 4; 10th focus group)

It can be vividly seen that they did not follow the necessary steps. They did not have active communication during the mid-point stage, and they did not work collaboratively when they should have been informed of each other's progress, discussing one another's sections and making comments to improve the content.

In contrast, a few participants complained that they would have liked to do this compilation collaboratively but one of the group members who had a very good writing skills and English language competency did the compilation by themselves without sending the final draft to the group seeking for further comments before submission:

I finished my part completely by halfway through week seven and it was due on the last day of week eight so I finished everything and I was ready it was all there in the assignment for her and she had done probably eighty per cent of hers but it was still messy and we needed to clean it up in order to make it ready to present… halfway through week eight I became a little bit stressed because I did not see any new results on it I did not see any responses to my e-mail and I thought ok there is a communication breakdown – so I sent her an e-mail with my phone number and I said you know if you need to contact me contact me tell me what is going on and she sent back a quite rude e-mail to me to say 'I will get it done and it will be done by the day'. So then I was sitting there stressing there was nothing else that I could really do and at 5pm exactly or I think it would may have been 4:59pm when the assignment was due she submitted the assignment without having sent me a copy to see first… well her writing ability is better than mine and I can 100 per cent understand why she did not want to give me the assignment before she handed in. (Participant 2; 5th focus group)

This finding is in line with previous research results (e.g., Zajac, 2017) showing that those group members who perceive that they have the capability of working alone and completing the task on their own do not seek other members' input. They are confident in their own skills and knowledge and prefer to work independently without exchanging information and updating group members with new information. Thus, the team would not be informed of the work done nor allowed to contribute the finishing touches.

The above discussion could be the most probable explanation for promoting shared leadership in student groups. Those participants who ended up doing the majority of the work called themselves the group leader though they believed that they were forced into this role because no one would contribute to finalising the assignment. Those who had to deal with dominant people in their group also felt deeply dissatisfied with the group atmosphere. On the contrary, students who believed in full collaboration at each stage of the group assignment were of the opinion that everyone should act as a leader and be accountable towards the whole assignment not just their own sections. They were able to develop a shared bond with one another and had more sense of dedication towards the task.

Assigning roles

During the completion stage, there are several tasks to do to prepare the final draft after compiling all the sections such as editing, proofreading, checking citations and formatting. Research participants who worked collaboratively during the previous stages of the group project discussed this together and made a collective decision about assigning specific roles at this stage considering each member's skills and expertise:

We decided at the end one team member because she was strong at editing, she was going to edit the whole all the research. She would have all the drafts through the discussion board and she would edit them herself then it would be sent to me to format and to reference and then I be the one to submit the assignment … we asked to do that because we knew we are good at it. (Participant 1; 2nd focus group)

We figured out each other's strengths and weaknesses so we could play it out at this stage specially when we have to write a report. For example, I have quite strong English skills so, you know, they might write their sections but I go through and I proofread for them, I paraphrase, change things and make sure everything makes sense and run smoothly. One of the other guys who was very good at graphic design and such, he is good at making PowerPoint and creating good presentation. (Participant 1; 1st focus group)

Assigning roles at this stage indicates collaboration among group members and drives a sense that they are still in it together to present a consistent assignment.

Share, discuss and receive comments before submission

This activity is also an important one towards promoting collaboration and gaining everyone's opinion on the final draft. Participants mentioned that group members did not provide comments leading to huge changes at this stage as they had done all the previous phases together. However, they shared the final draft with each other to make sure that everyone was happy with it:

everyone had done their assigned part by the date that we wanted to have it and then one person compile it together and made sure it was sound like it was from one voice … actually the person who compiled it sent it through WhatsApp and she said, I have compiled it together and this is what it looks like [and] she asked for feedback to make sure it was OK… we all were very content with it. (Participant 1; 9th focus group)

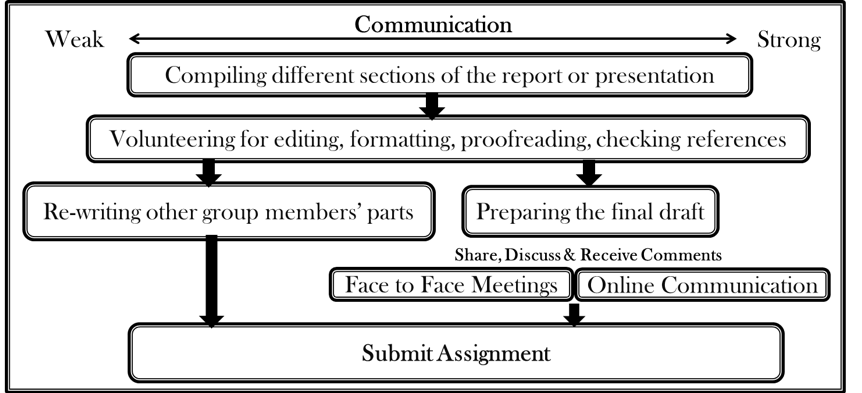

Students' information behaviour and their collaborative activities in the last stage of completing group assignments is illustrated in Figure 3. The main activity at this stage is synthesising the information gathered by group members. Organising different pieces of information in a structured way and making a connection between distinct sections is a highly complex process. Students should discuss their specific skills related to formatting, editing and proofreading, and share the responsibility to create a consistent representation. Lack of communication at this stage could lead to consequences such as the majority of the work being done the night before submission by those students who were more committed to completing the task. Some participants indicated that they found themselves being a finisher of the task because someone had to finish and submit the assignment.

Figure 3: Students' collaborative activities and information behaviour during phase three (completion stage)

Conclusion

The findings of this study show that division of labour is a common strategy in student groups, similar to previous research (e.g., Leeder and Shah, 2016; Wu, Liang and Yu, 2018). The majority of groups that were assigned a general subject, conducted background research which enabled them to come up with different ideas and thoughts. They collaboratively worked on the ideas and they chose their topic mainly based on availability and accessibility of resources and feasibility of the project. On the other hand, there were some groups that had been assigned pre-selected subtasks and they divided these tasks among themselves during the first meeting without performing any background research or working collaboratively on clarifying and understanding what they were asked for. Student groups with this type of behaviour believed in nominating someone as a leader to take control of the overall situation (Wu, Liang and Yu, 2018). However, the groups that started working on their assignment collaboratively were of the opinion that putting one person in charge of the whole assignment is not fair and exerts negative influence on their collaborative work.

The results of this study also show that students usually search for and retrieve relevant information from databases individually because each has their own subtopics; however, that does not mean that they cannot work collectively. Those participants who believed they had successful group work had frequent communication and information exchange throughout the process to evaluate and assess each member's progress which led to improving the whole content. In particular, they worked more efficiently during the final stage when they had to synthesise different pieces of information to compose the final representation. Although, appointing someone as a leader has been emphasised in the group work literature, the results of this research and similar studies (e.g., Croy and Eva, 2018; Hernández Pérez, 2015) revealed that shared leadership plays a key role in developing and maintaining collaboration among students as each member should have the same level of responsibility toward the task.

Task type is another determining factor in this process and it has been discussed widely that complex and ill-structured topics are the most suitable ones for group assignments (e.g., Allchin, 2013; Kirschner, Paas and Kirschner, 2011). However, the findings of this study showed that students are still working on group assignments which they can easily divide it into subtasks without formulating the information need collaboratively and a necessity to do background research to come up with creative ideas. These participants clearly mentioned that they did not need to discuss one another's strengths and special expertise because the assignment was not difficult, thus they randomly divided the subtopics among themselves. Hence, instructors should give proper consideration to the structure of the group task to enhance the collaboration over the course of the group project. Furthermore, it seems that students require more training and instruction in regard to conducting a group task. There is a widely-held belief among students that group assignments should be divided evenly among members to be considered fair; however, the tasks with high interdependence require all group members to work together at the same time. More importantly, students should be informed that a careful collaboration can help the team to create a solution or a product that is more than the sum of individual contributions (Shah, 2008). Thus, educators should devote more attention to monitoring the students' progress and their collaborative and individual activities at different stages and highlighting the importance of maintaining strong and active communication over the course of the group project. Hence, it is of great significance to shift the emphasis from assessing the final document to evaluating how well students work together.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. The author also acknowledges the support from the School of Science, Edith Cowan University.

The author is deeply grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the regional editor, Dr. Cossham, for their constructive and helpful comments.

About the author

Parisa Khatamian Far is a PhD candidate in Library and Information Science at Edith Cowan University. Parisa's research interest is exploring students' information behaviour in the context of group work and identifying the factors which drive them to engage in collaborative information behaviour activities. She can be contacted at p.khatamianfar@ecu.edu.au

References

- Allchin, D. (2013). Problem-and case-based learning in science: an introduction to distinctions, values, and outcomes. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 12(3), 364-372.

- Azzopardi, L., Pickens, J., Sakai, T., Soulier, L. & Tamine, L. (2016). Report on the first international workshop on the evaluation on collaborative information seeking and retrieval (ECol'2015). SIGIR Forum, 50(1), 42-48.

- Azzopardi, L., Pickens, J., Shah, C., Soulier, L. & Tamine, L. (2018). Report on the second international workshop on the evaluation on collaborative information seeking and retrieval (ECol'2017@ CHIIR). SIGIR Forum, 51(3), 122-127.

- Barbour, R. (2008). Doing focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

- Bilal, D. (2002). Children's use of the Yahooligans! Web search engine. III, Cognitive and physical behaviors on fully self-generated search tasks. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(13), 1170-1183.

- Bruce, H., Fidel, R., Pejtersen, A. M., Dumais, S., Grudin, J. & Poltrock, S. (2003). A comparison of the collaborative information retrieval behaviour of two design teams. New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 4(1), 139-153.

- Chiriac, E. H. & Granström, K. (2012). Teachers’ leadership and students’ experience of group work. Teachers and Teaching, 18(3), 345-363.

- Cooley, S. J., Burns, V. E. & Cumming, J. (2015). The role of outdoor adventure education in facilitating groupwork in higher education. Higher Education, 69(4), 567-582.

- Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). London: Sage Publications

- Croy, G. & Eva, N. (2018). Student success in teams: intervention, cohesion and performance. Education + Training, 60(9), 1041-1056.

- Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Fisher, K. E., Erdelez, S. & McKechnie, L. E. F. (Eds.). (2005). Theories of information behavior. Medford, NJ: Information Today.

- Gibbs, A. (1997). Focus groups. Social Research Update, 19. Retrieved from http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU19.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6Ek2L7Mva)

- González-Ibáñez, R., Haseki, M. & Shah, C. (2013). Let’s search together, but not too close! An analysis of communication and performance in collaborative information seeking. Information Processing & Management, 49(5), 1165-1179.

- Hernández Pérez, O. (2015). Collaborative information behaviour in completely online groups: exploring the social dimensions of information in virtual environments. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 4(4), 775-787.

- Hertzum, M. & Hansen, P. (2018). Empirical studies of collaborative information seeking: a review of methodological issues. Journal of Documentation, 75(1), 140-163.

- Hyldegård, J. (2006). Between individual and group: exploring group members’ information behaviour in context. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Retrieved from http://pure.iva.dk/files/31034780/jette_hyldegaard_phd.pdf

- Karunakaran, A., Reddy, M. C. & Spence, P. R. (2013). Toward a model of collaborative information behavior in organisations. Journal of the American Society for information Science and Technology, 64(12), 2437-2451.

- Kirschner, F., Paas, F. & Kirschner, P. A. (2011). Task complexity as a driver for collaborative learning efficiency: the collective working-memory effect. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(4), 615–624.

- Kriflik, L. & Mullan, J. (2007). Strategies to improve student reaction to group work. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 4(1), article 3. Retrieved from https://jutlp.uow.edu.au/2007_v04_i01/pdf/kriflik_009.pdf (Archived by the Internet Achive at https://bit.ly/2OYrjgY)

- Kuhlthau, C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(6), 361-371.

- Leeder, C. & Shah, C. (2016). Strategies, obstacles, and attitudes: student collaboration in information seeking and synthesis projects. Information Research, 21(3), paper 723. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/21-3/paper723.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6kRgPiIJh)

- Limberg, L. (1999). Experiencing information seeking and learning: a study of the interaction between two phenomena. Information Research, 5(1), paper 68. Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/5-1/paper68.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5cwrZVX6b)

- Ndumbaro, F. & Mutula, S. (2019). Applicability of solitary model of information behaviour in students’ collaborative learning assignments. Information and Learning Sciences, 120(3/4), 190-207.

- Oliver, B., Whelan, B., Hunt, L. & Hammer, S. (2011). Accounting graduates and capabilities that count: perceptions of graduates, employers, and accounting academics in four Australian universities. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 2(1), 2-27.

- Reddy, M. C. & Dourish, P. (2002). A finger on the pulse: temporal rhythms and information seeking in medical work. In E.F. Churchill and J. McCarthy (Eds.), Proceedings of 2002 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (pp. 344-353). New York, NY: ACM.

- Reddy, M. C. & Jansen, J. A. (2008). Model for understanding collaborative information behaviour in context: a study of two healthcare teams. Information Processing and Management, 44(1), 256-273.

- Saleh, N. (2012). Collaborative information behaviour in learning tasks: a study of engineering students. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). McGill University, Montreal, Canada. Retrieved from http://digitool.Library.McGill.CA:80/R/-?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=114447&silo_library=GEN01

- Shah, C. (2014). Collaborative information seeking. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(2), 215-236.

- Shah, C. (2008). Toward collaborative information seeking (CIS). Paper presented at the Proceedings of IEEE ACM Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL) Workshop on Collaborative Information Retrieval, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Shah, C. & Leeder, C. (2016). Exploring collaborative work among graduate students through the C5 model of collaboration: a diary study. Journal of Information Science. 42(5), 609-629.

- Shah, C., Capra, R. & Hansen, P. (2015). Workshop on social and collaborative information seeking (SCIS). SIGIR Forum, 49(2), 117-122.

- Shah, C. & González-Ibáñez, R. (2010). Exploring information seeking process in collaborative search tasks. Proceedings of the ASIS&T Annual Meeting, 47, article 60. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/meet.14504701211/pdf

- Shah, C., Hansen, P. & Capra, R. (2012). Report on the second workshop on collaborative information seeking: New Orleans, 12 October, 2011. Information Research, 17(2), paper 520. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/17-2/paper520.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810053048/http://InformationR.net/ir/17-2/paper520.html)

- Sonnenwald, D. H. & Pierce, L. G. (2000). Information behavior in dynamic group work contexts: interwoven situational awareness, dense social networks and contested collaboration in command and control. Information Processing & Management, 36(3), 461-479.

- Tao, Y. & Tombros, A. (2013). An exploratory study of sensemaking in collaborative information seeking. In P. Serdyukov, P. Braslavski, S.O. Kuznetsov, J. Kamps, S. Rüger, E. Agichtein, I. Segalovich, and E. Yilmaz (Eds.), Advances in Information Retrieval: 35th European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2013, Moscow, Russia, March 24-27, 2013, Proceedings (pp. 26-37). Berlin: Springer.

- Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270.

- Wilson, T.D. and Walsh, C. (1996). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. Sheffield: University of Sheffield Department of Information Studies, 1996.

- Wu, D. & Yu, W. (2015). Undergraduates’ team work strategies in writing research proposals. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference Companion on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (pp. 199-202). New York, NY: ACM.

- Wu, D., Liang, S. & Yu, W. (2018). Collaborative information searching as learning in academic group work. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 70(1), 2-27.

- Yue, Z. & He, D. (2010). Exploring collaborative information behavior in context: a case study of E-discovery. Paper presented at the ACM 2010 conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) Workshop on Collaborative Information Seeking, Savannah, GA.

- Zajac, S. A. (2017). Diversity in design teams: a grounded theory approach. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Rice University, Houston, Texas, USA. Retrieved from https://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/96181/ZAJAC-DOCUMENT-2017.pdf?sequence=7&isAllowed=y