published quarterly by the university of borås, sweden

vol. 24 no. 4, December, 2019

Introduction. The aim of the study was to observe the propensity of actively avoiding information among the youth and explore whether their demographics and information literacy self-efficacy have any influence on this tendency.

Method. An online questionnaire survey was conducted and young people between 15 and 29 from different countries in Europe participated. Out of 7,368 responses, 3,324 complete responses were selected for further analysis.

Analysis. Frequency analysis, and mean comparison were used to understand the extent of information avoidance within the youth. Linear regression analysis was used to explore the influence of demographics, and information literacy self-efficacy on information avoidance.

Results. The study revealed that approximately 25 % of the respondents would actively avoid information if they suspect it to be negative. The result indicated that higher education and higher information literacy self-efficacy can reduce the propensity of information avoidance. It was also observed that the respondents coming from rural areas and respondents who are not employed are more inclined to avoid information.

Conclusions. The study indicated that one-fourth of the youth are likely to avoid challenging information in their daily lives. The result underlines the omnipresence of information avoidance as a natural part of everyday life information behaviour. The result also discloses the link between education, information literacy, and information avoidance which paves the path for future research.

Information avoidance is the process of preventing or delaying the acquisition of available but potentially unwanted information (Sweeny et.al., 2010). Although, intuitively, more information is thought to produce better clarity, people are not always willing to acquire information; rather, on many occasions they actively or passively avoid information (Golman, Hagmann, and Loewenstein, 2017). Despite its omnipresence in everyday information seeking behaviour, information avoidance has remained an understudied behaviour phenomenon, although acknowledged in some studies (Narayan, Case & Edwards, 2011; Case et al, 2005; Hirvonen et al., 2012). In addition, information avoidance has been, so far, largely studied in relation to complex information acquisition contexts, e.g. in the context of diagnosis and treatment of diseases (Case et al., 2005), meaning we lack an understanding of information avoidance in more everyday contexts and situations.

Young people are the main actors in this information era (Öktem et.al., 2014) who constitute an important part of the citizenry (OECD, 2012). Therefore, studying their propensity of avoiding information in everyday life is relevant. Information avoidance is the mechanism of temporarily preventing the acquisition of information, and this tendency could potentially lead to impaired decision making (Golman, Hagmann, and Loewenstein, 2017). Therefore, studying the tendency of young people’s information avoidance in their daily lives is necessary. Knowledge about such tendencies may be used to design inclusive information services and curriculum to enhance information literacy among youth. However, there are few studies on information avoidance within the young population. In response to this research gap, this study explores information avoidance among youth in the context of everyday life. The study observes the information avoidance propensity among young people and explores possible factors that may influence their tendency to avoid information, such as demographics, education and information literacy.

Information avoidance is defined and studied in various domains and the concept has different meanings depending the context in focus. In the domain of psychology, the tendency of avoiding information is termed as selective exposure (Rogers, 2010); i.e. avoiding information that does not agree with the receiver’s worldview. Psychologists have found that information-seeking is influenced by stress and includes coping mechanisms such as repression, blunting and rejection of information whereby a person voluntarily or involuntarily blocks out some informational fields and pathways (Miller & Mangan, 1983; Krohne, 1993; Covington & Mueller, 2001). Within the domain of economics, Golman, Hangman, and Loewenstein (2017) showed that people deliberately bypass information if they deem it likely to cause mental discomfort, cognitive dissonance or increase uncertainty. This occurs irrespective of the utility of the information. Individuals generally tend to expose themselves to information that is already in accordance with interests, needs and attitudes but avoid information that contradicts them.

Information avoidance has mostly been studied in the context of health-related information and in this context it has long been found that avoiding information may be a deliberate attempt to cope (Barbour et al., 2012; Case & al., 2005; Howell, Ratliff & Shepperd, 2016).). Studies on physical health indicate that information regarding a health condition may increase wellbeing for people who actively consult information as part of their coping response, while it increases anxiety for those who cope by avoidance (Miller, 1987; Ek & Heinström, 2011). Patients diagnosed with cancer, for example, may actively avoid information about their condition as it increases their anxiety (e.g. Persoskie, A., Ferrer, R. A., & Klein, 2014; Chae, Lee, & Kim, 2019). In the context of genetic testing, avoiding information may be a conscious decision in an attempt to avoid anxiety and depression (Case et al., 2005).

In the domain of information science, Savolainen (2007) postulated that people avoid unnecessary or negative information by filtering it and withdrawing in their everyday life. He described filtering as weeding out material deemed useless while withdrawal refers to the need to protect oneself from excessive information supply. Fisher et al. (2005) observed that the individual coping styles as suggested by Miller (1987), i.e. monitoring (active information seeking about one’s problem) and blunting (avoidance of threatening information or attempts to distract oneself from challenges), are important aspects of information behaviour. Information-seeking is influenced by stress and includes coping mechanisms such as repression, blunting and rejection of information (Miller & Mangan, 1983; Krohne, 1993; Covington & Mueller, 2001). Narayan, Case, and Edwards (2011) showed that active avoidance in everyday life was a short-term rejection of information that suggested a stress-coping mechanism. Thus, information avoidance could be instrumental for maintaining hope, and through this, a capacity to carry on everyday life (Leydon et al., 2000). Narayan, Case, and Edwards (2011) found participants would deliberately ignore potential negative information about religion, finances, relationships and family in their daily lives. The researchers postulated that we all live in daily uncertainty about the larger questions of life and the universe, as well as our very lives. Religion, money, relationships, and family are important aspects of most people's lives, which provide them with a concrete sense of stability and continuity through a denial of uncertainty and a sense of determinism. Consequently, these were the most problematic areas where participants had to use mechanisms such as blunting and coping (Miller & Mangan, 1983) in respect to any information that created uncertainty. People experience different information needs in identical situations because they have different understandings of these situations based on their experience and other factors unique to them. Therefore, the information people seek and decide to avoid is diversified and unique. To what extent a person is open to confront uncertainty depends not only on individual factors such as self-efficacy and coping skills, but also on socio-cultural factors (Sorrentino, and Roney, 2000).

Sweeny et al. (2010) have defined information avoidance as any behaviour that prevents or delays the acquisition of information that could be potentially unwanted. They suggest that people avoid information for three primary reasons: 1) the new information may demand a change in beliefs, 2) the information may demand undesired action and 3) the information itself may cause unpleasant emotions. Studies have found that people both actively and passively avoid information in their everyday life (Narayan, Case, and Edwards, 2011). Passive information avoidance could involve failure to understand the content of information or undermining the importance of information unconsciously. On the other hand, active information avoidance may involve deliberately avoiding inquiry about one’s own delicate problem or actively avoiding reading news that may trigger any cognitive dissonance (Sweeny et al., 2010).

There are situational factors that influence whether people will seek or avoid certain information. These are linked to how strongly a person perceives 1) his/her control over the consequences of getting the information, 2) his/her abilities to cope with the information and 3) how easy obtaining or interpreting the information is. Information avoidance may also depend on expectations of the content of the information (Sweeny et al., 2010). McCloud et. al. (2013) found that if a person has difficulty in finding information or finds it difficult to comprehend, (s)he is more likely to avoid this information.

This study positions information avoidance as a part of everyday life, thus as a conscious choice or reaction to the information flow in everyday life. Active information avoidance may hence be a conscious decision or an automatic reaction to the information flow in everyday life. Many information-seeking studies have established that people look for and acquire information in their everyday lives in order to reduce uncertainty or make sense of or give meaning to their world (Kuhlthau, 1993; Dervin, 1992). In contrast, there has been little research on people’s tendency to avoid information. To respond to that research gap, the present empirical study was conducted to investigate information avoidance of youth and the influence of their demographics and information literacy on their propensity of information avoidance.

Information avoidance among youth as regards their propensity to avoid delicate information about themselves has not been studied much separately. In this information era, young people are seen as the main actors in a variety of processes (Öktem et.al., 2014). They constitute an important part of citizenry and it is important that they realize their capacity as useful, valuable and reflective citizens (OECD, 2012). On the other hand, the consequences of such collective information avoidance may have adverse outcomes. Research findings indicate that collective information avoidance can lead to, poor public health (Golman et. al., 2017), spread of diseases (Golman et. al., 2017), ethical transgression (Bazerman et. al., 2016) and political polarization (Druckman et. al., 2013). For these reasons, understanding whether young people in society actively avoid information because they sense it is negative, it may trigger anxiety or it is related to their delicate problem(s), is pertinent. This study reveals whether this propensity to avoid information is related in any way to the youth’s demographic background and their information literacy self-efficacy.

The aim of this research is to observe young people’s propensity to avoid undesirable information and the influence of their ‘demographics’(age, gender, education, living area, and current employment status) and ‘information literacy self-efficacy’ on the tendency to avoid information in challenging situations. The research questions therefore are:

To find the answers to these questions, previous studies and literature were reviewed to build the major constructs such as ‘information avoidance’, ‘information literacy self-efficacy’ and ‘demographics’. In this study, we considered information literacy self-efficacy and demographics as the predictive variable while ‘information avoidance’ as the outcome variable.

The dataset used for this paper was a part of a larger survey which studied the everyday life information seeking behaviour of the young people across different European countries (Karim, and Widén, 2018). After developing the framework and the research questions, the data on information avoidance was separated to understand young people’s frequency of avoiding challenging information in their everyday information behaviour. This step answers the first research question.

To find answers to the second research question, the propensity to avoid information was measured against the demographics of the young people. This was an attempt to see if age, gender, education, occupation, and living area have any influence on the tendency to avoid challenging information. Previous research has shown that there is a connection between demographics and information avoidance, e.g. McCloud et al. (2013) have found that people who are young and female with debt or lower income are more likely to avoid information. Jean et.al. (2017) observed information avoidance associated with education, household income, occupational status, self-efficacy, and cancer-related health information. They found that people with lower educational attainment are more likely to avoid cancer-related information. The tendency was same with people who are retired, unemployed or disabled. There are also indications that people with a low income and greater debt avoid information more. Female participants, in general, were more likely to avoid information than men, but when combining different demographics, it appeared that the group which avoided information the most was young men (McCloud et al., 2013).

To find an answer to the third research question, the construct of information avoidance was compared to the information literacy self-efficacy of the young respondents. This was to understand if a young individual’s information literacy self-efficacy influences his/her tendency to avoid challenging information while navigating in everyday information seeking. Previous research among cancer patients has found that patients with lower information literacy self-efficacy were seen to perceive information as difficult to use or comprehend and would prefer avoiding information regarding possible cancer infliction (St. Jean, Jindal, and Liao, 2017; Sweeny, Melnyk, Miller, and Shepperd, 2010).

To observe the general tendency of information avoidance along with the everyday life information seeking behaviour of the youth, an online survey was carried out. The online survey was distributed to 18 countries in Europe through the network of The European Youth Information and Counselling Agency. Data was collected from 1 November 2017 until 28 February 2018 through the platform of Survey Monkey. With a convenience sampling of young people, a total of 7,368 responses were collected (Karim, and Widén, 2018). However, the sample was not particularly representative since young people from some countries were more represented than that from the others. To keep the N constant in every measurement, we have considered the complete responses only. Additionally, the survey was aimed at Europe’s the young population between the ages of 15 and 29. Therefore, all the responses falling outside this criterion were removed. Finally, a total of 3,324 (45 %) (N=3,324) complete responses were considered for further analysis.

Table 1 elaborates the demographical features of the respondents. The sample group was female dominated. The majority of them attended either secondary or upper secondary schools. The average age of the respondents was 19 years. Each respondent answered 13 different questions. Of these 13 questions, 6 questions collected data concerning their demographics. ‘Information avoidance’ was measured by 3 items and ‘information literacy’ was calculated using 4 items. A 5-point Likert scale was used to measure ‘information avoidance’ and ‘information literacy’,; the lowest point represented strong disagreement while the highest point represented strong agreement.

| Measure | Items | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1213 | 36.5 % |

| Female | 2060 | 62.0 % | |

| Other | 51 | 1.5 % | |

| Education | Lower (primary school) | 278 | 8.4 % |

| Secondary school (gymnasium) | 1303 | 39.2 % | |

| Vocational upper secondary school | 364 | 11.0 % | |

| General upper secondary school (lyceum) | 636 | 19.1 % | |

| Higher education - Bachelor (BA) | 413 | 12.4 % | |

| Higher education – Master (MA) or higher | 330 | 9.9 % | |

| Age | 15–19 | 2159 | 65.0 % |

| 20–24 | 645 | 19.4 % | |

| 25–29 | 520 | 15.6 % | |

| Living Area | Large city (population over 50,000 persons) | 1071 | 32.2 % |

| Medium-sized city (population 10,000–50,000 persons) | 911 | 27.4 % | |

| Small town (population under 10,000 persons) | 648 | 19.5 % | |

| Rural area/village | 694 | 20.9 % | |

| Employment Status | I am attending school (primary or secondary). | 1845 | 55.5 % |

| I am studying at university or polytechnic. | 459 | 13.8 % | |

| I am working. | 418 | 12.6 % | |

| I am studying and working. | 355 | 10.7 % | |

| I am looking for work, I am unemployed. | 191 | 5.7 % | |

| I am not working and not studying and not looking for work. | 31 | 0.9 % | |

| I am at home taking care of my children and family. | 25 | 0.8 % |

To ensure the content validity of the scales that were used in the study, the items selected for the constructs of ‘information avoidance’, and ‘information literacy self-efficacy’ should display a strong consistency to qualify as a valid construct.

In this paper, the two constructs that had multiple items in them were ‘information literacy self-efficacy’ and ‘information avoidance’. The content validity of each of the constructs was established from existing research and by adopting items based on earlier studies (Table 2). Information avoidance was measured with three items from the 'blunting' scale of the everyday information mastering (EIM) scale developed by Heinström et al. (no date). The three statements were ‘Sometimes I do not want to hear news about myself if I suspect it to be bad’, ‘I avoid reading a piece of news if the title makes me feel anxious’, ‘If I have a delicate personal problem I don’t even want to read texts related to them’.

Information literacy self-efficacy was measured with four statements, i.e. ‘I am able to identify what type of information source I need for different information needs’, ‘I am able to evaluate the scope and content of the chosen resources’, ‘I can examine and compare information from various sources in order to evaluate reliability, validity, accuracy, authority, timeliness, or bias’, ‘I can identify sources with alternative viewpoints to provide context and balance’. All the items are backed by relevant literature and previous studies (Table 2).

| Constructs | Items | Literary terminology | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information avoidance | Sometimes I do not want to hear news about myself if I suspect it to be bad. | Risk aversion | Kőszegi, 2010 |

| I avoid reading a piece of news if the title makes me feel anxious. | Anxiety | Maslow, 1963 | |

| If I have a delicate personal problem, I don’t even want to read texts related to them. | Regret aversion | Golman, Hagmann, and Loewenstein, 2017 | |

| Information literacy | I am able to identify what type of information source I need for different information needs. | Realizing information needs and sourcing | Serap Kurbanoglu, Akkoyunlu, and Umay, 2006 |

| I am able to evaluate the scope and content of the chosen resources. | Evaluation | Bundy, 2004 | |

| I can examine and compare information from various sources in order to evaluate reliability, validity, accuracy, authority, timeliness, or bias. | Examine and compare | Bundy, 2004 | |

| I can identify sources with alternative viewpoints to provide context and balance. | Critical thinking | Serap Kurbanoglu, Akkoyunlu, and Umay, 2006 |

Information avoidance was measured at a personal level and the propensity of risk aversion, regret aversion, and anxiety driven information avoidance was tested as three different items. Information literacy measurement items were collected from the Information Literacy Standard (Bundy, 2004) and Information Literacy Self-efficacy scale proposed by Serap Kurbanoglu (2006). The four major competencies of Information Literacy i.e. 'Realizing Information Needs and Sourcing', 'Information Evaluation', 'Information Examine and Compare', and 'Critical Thinking' were selected to measure Information Literacy Self-Efficacy.

In Table 3, the final set of 7 questionnaire items display mean, standard deviation, average variance and Cronbach’s Alpha. Both constructs, ‘information avoidance’ and ‘information literacy’, exceed the recommended standard for reliability; the constructs displayed >0.70 Cronbach's α >0.70 and > 0.50 average variance > 0.50 (Cronbach, 1970).

| Measure | Items | Mean | Std. deviation | Average variance | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information literacy | Info.Lit1 | 3.6932 | 0.74058 | 0.548 | 0.86 |

| Info.Lit2 | |||||

| Info.Lit3 | |||||

| Info.Lit4 | |||||

| Information avoidance | Info.Av1 | 2.6143 | 0.91758 | 0.842 | 0.72 |

| Info.Av2 | |||||

| Info.Av3 |

Out ff the 3,324 respondents, 33 % avoid risk by refraining from listening to any news that is suspected to be bad, 23 % avoid anxiety by not reading any piece of information suspected to raise discomfort, and 21 % were found avoiding texts that discuss their delicate personal problems. The percentages were calculated by adding the number of responses that ‘Agreed’ or ‘Strongly Agreed’ with the statements. The mean of the construct is 2.61 and the standard deviation 0.91. The propensity of information avoidance was also observed in relation to the demographic variables.

| Information avoidance | N | % | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sometimes I do not want to hear news about myself if I suspect it to be bad. | 3 324 | 33 % | 2.85 | 1.18 |

| I avoid reading a piece of news if the title makes me feel anxious. | 3 324 | 23 % | 2.54 | 1.15 |

| If I have a delicate personal problem, I don’t even want to read texts related to them. | 3 324 | 20 % | 2.45 | 1.18 |

The first research question uncovers the general tendency of youth to avoid challenging information. It was observed that 20 % to 33 % of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they do avoid information they perceive to be challenging, risky or anxiety-inducing. The construct of information avoidance was measured with three different statements. The frequency of information avoidance observed among the youth is described in Table 5. The respondents who scored 4 and above on the Likert scale were considered information avoiders.

| Demographics | Total | % of N | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| **Gender** | |||

| MALE | 134 | 11 % | 1,213 |

| FEMALE | 215 | 10 % | 2,060 |

| OTHER | 4 | 8 % | 51 |

| **Age** | |||

| Age group 1 | 242 | 11 % | 2,159 |

| Age group 2 | 49 | 8 % | 645 |

| Age group 3 | 62 | 12 % | 520 |

| **Education** | |||

| Lower (primary school) | 29 | 10 % | 278 |

| Secondary school (gymnasium) | 138 | 11 % | 1,303 |

| Vocational upper secondary school | 52 | 14 % | 364 |

| General upper secondary school (lyceum) | 70 | 11 % | 636 |

| Higher education - Bachelor (BA) | 38 | 9 % | 413 |

| Higher education – Master (MA) or higher | 26 | 8 % | 330 |

| **Living Area** | |||

| Large city (population over 50,000 persons) | 97 | 9 % | 1,071 |

| Medium-sized city (population 10,000-50,000 persons) | 99 | 11 % | 911 |

| Small town (population under 10,000 persons) | 78 | 12 % | 648 |

| Rural area/village | 79 | 11 % | 694 |

| **Employment Status** | |||

| I am attending school (elementary or secondary). | 199 | 11 % | 1,845 |

| I am studying at university or polytechnic. | 44 | 10 % | 459 |

| I am working. | 44 | 11 % | 418 |

| I am studying and working. | 29 | 8 % | 355 |

| I am looking for work, I am unemployed. | 26 | 14 % | 191 |

| I am not working and not studying and not looking for work. | 7 | 23 % | 31 |

| I am at home taking care of my children and family. | 4 | 16 % | 25 |

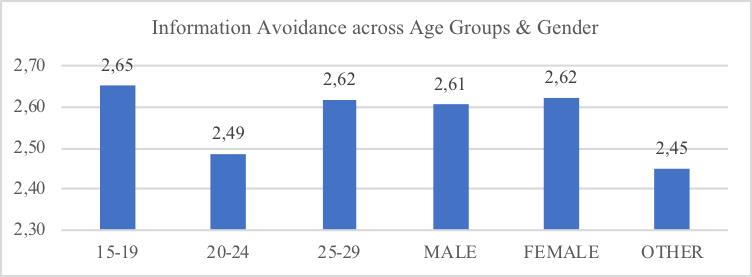

The average mean of the construct ‘information avoidance’ was measured in relation to the three age groups. It indicates that the youngest and the oldest group are more inclined towards information avoidance. In this study, gender was less decisive in information avoidance; the results were quite similar across males and females.

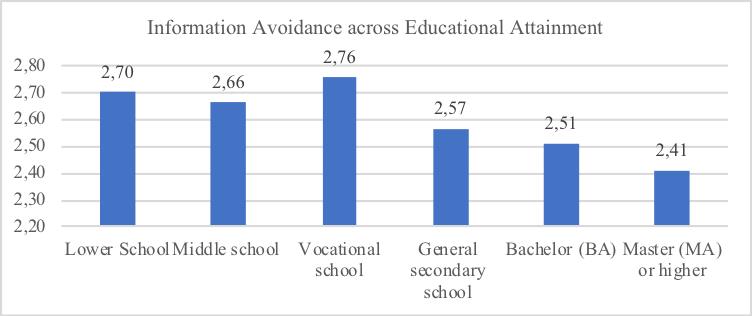

On the other hand, education apparently seems to play a role in reducing the tendency to avoid information. While in the primary, secondary and vocational respondents have a mean of 2.6 to 2.7,the mean drops as the level of education rises to higher education. Compared to vocational school students, the tendency to avoid information was seen to be much lower among the bachelor and baster’s degree students.

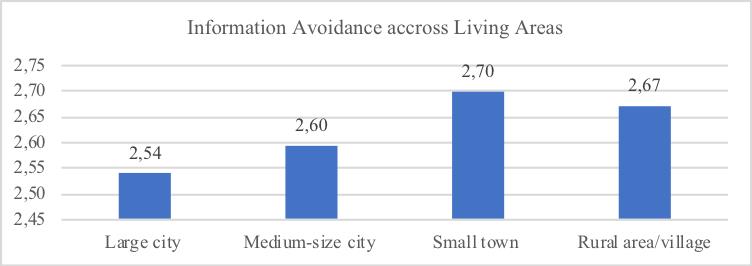

There was also apparent distinction observed in the information avoidance tendency between the residents of larger cities and smaller towns or rural areas. While the population belonging to larger cities reported an average mean of 2.5, the tendency was higher in the smaller towns and rural areas.

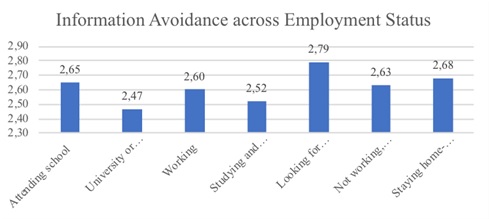

The tendency to avoid information varied across the different employment statuses. The respondents who are working or working while studying have a lower mean of information avoidance compared to those who are not employed, looking for employment or staying home.

To observe the correlation amongst all the variables a bivariate correlation was conducted.

| Info_Avoidance | Info_Lit | Education | Gender | Living Area | Employment | Age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Info_Avoidance | Pearson Correlation | 1 | -.100** | -.093** | 0,000 | .062** | -0,007 | -.037* |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,990 | 0,000 | 0,701 | 0,031 | ||

| Info_Lit | Pearson Correlation | -.100** | 1 | .132** | .053** | -.110** | 0,024 | .135** |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,002 | 0,000 | 0,165 | 0,000 | ||

| Education | Pearson Correlation | -.093** | .132** | 1 | .070** | -.208** | .540** | .722** |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | ||

| Gender | Pearson Correlation | 0,000 | .053** | .070** | 1 | -.050** | .063** | .079** |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,990 | 0,002 | 0,000 | 0,004 | 0,000 | 0,000 | ||

| Living Area | Pearson Correlation | .062** | -.110** | -.208** | -.050** | 1 | -.147** | -.204** |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,004 | 0,000 | 0,000 | ||

| Employment | Pearson Correlation | -0,007 | 0,024 | .540** | .063** | -.147** | 1 | .666** |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,701 | 0,165 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | ||

| Age | Pearson Correlation | -.037* | .135** | .722** | .079** | -.204** | .666** | 1 |

| Sig. (2 - tailed) | 0,031 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 | 0,000 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

The bivariate correlation indicated that the tendency of information avoidance has a significant negative correlation with education and information literacy self-efficacy (β= -0.093, P= 0.000) (β= -0.10, P= 0.000). Additionally information literacy self-efficacy seemingly had a positive correlation with education (β= 0.132, P= 0.000)

The next step in the study was to perform a multiple regression analysis on the demographic variables and information literacy as predictive variables with information avoidance as the outcome variable. The predictive variables were age, gender, education, living area, current employment status and information literacy self-efficacy.

The overall model describes a moderate correlation between the predictive variables and the outcome variable, as a combination of the demographics and information literacy self-efficacy can predict the extent of information avoidance. The result shows R= 0.15 and P (Sig.) 0.00 (P < 0.05). This indicates that the relationship between information avoidance, demographics and information literacy is statistically significant.

| Constructs | Unstandardized β coefficients | P(Sig.) |

|---|---|---|

| Information Literacy | -0.160 | 0.000 |

| Education | -0.079 | 0.000 |

| Gender | 0.018 | 0.573 |

| Living Area | 0.035 | 0.017 |

| Employment Status | 0.026 | 0.113 |

| Age | 0.006 | 0.620 |

Table 6 above provides a summary of each variable and its influence on the propensity to avoid information. Of the 6 predictive variables, we can see that age (β= 0.006, P= 0.62) and gender (β= 0.018, P= 0.57) and employment status (β= 0.026, P= 0.113) were not statistically significant in predicting information avoidance tendency. On the other hand, both variables, information literacy and education, seem to have a negative correlation with information avoidance. Both variables show significant negative influence on the propensity to avoid information. Education (β= -0.079, P= 0.000) shows a negative correlation on information avoidance. This indicates that the higher the level of education, the lower is the tendency to avoid information. Similar influence was found between information literacy self-efficacy and information avoidance. Information literacy self-efficacy (β= -0.160, P= 0.000) seems to have strong negative influence on the tendency to avoid information. Like education, this result indicates that a higher level of information literacy self-efficacy would reduce the propensity to avoid information.

The aim of the present study was to observe information avoidance propensity of young people across Europe. The results indicate that around 25 % of the respondents would actively avoid information which might pose risk of raising anxiety, embarrassment or discomfort. The constructs age and gender were not significant in influencing the propensity to avoid challenging information. This outcome contradicts the study by McCloud et al. (2013) whereby people who are young, female with debt or lower income are more likely to avoid information. However, McCloud’s study was conducted on cancer patients; in such challenging situations age and gender may have played a more significant role. The outcome in the present study indicates that information avoidance in everyday life is less influenced by age and gender. Regarding living area and employment status, information avoiders showed some distinction with low information avoiders. It was observed that the respondents who scored 4 to 5 in information avoidance live mostly in smaller towns and rural areas, while the low information avoiders were mostly from medium or large cities. It was also clear in the results that the information avoiders were mostly either unemployed, looking for employment, or were at home looking after family. These outcomes corresponded with the findings of Jean et. al. (2017) in their research on the influence of demographics among cancer patients in their tendency to avoid information . Compared to previous studies, our results suggest that age and gender have a stronger influence on information avoidance in charged situations, while living area and employment status seems to influence information avoidance equally strongly across contexts. These preliminary findings need to be tested further in future research.

The other two constructs out of the six, i.e. education and information literacy self-efficacy were found to influence information avoidance. The information avoiders had a lower level of education; students from elementary and vocational schools showed a higher tendency to avoid information as opposed to the respondents who attained higher education. Similarly, respondents who were more confident about their information literacy scored less on the scale of information avoidance. The influence of education and information literacy on information avoidance correspond with the findings of Jean et. al. (2017) in their research on cancer patients. The respondents who had a higher information literacy self-efficacy avoided information to a lesser extent. Previous research has similarly found a connection between information avoidance and signs of low information literacy (McCloud et al., 2013).

Both the predictive variables, i.e. education and information literacy, had a negative correlation with information avoidance tendency, which also indicates that higher education and information literacy self-efficacy reduces repression, and blunting in handling potentially negative information. An increase in education and in information literacy seem to reduce information avoidance propensity. This indicates that a higher education may lead to a less emotionally-driven approach toward information. Highly educated people may e.g. understand the importance of information that may not be pleasant, and so choose not to avoid it despite potential negative emotionality. Like education, the construct of information literacy self-efficacy also displayed a negative correlation with information avoidance. The link between information literacy self-efficacy and information avoidance could partially be explained by low information literacy, making information more difficult to comprehend, and therefore lead to more information avoidance due to difficulty in understanding (confirming McCloud, 2013). An increase in information literacy could, therefore, potentially reduce information avoidance propensity.

The present study aimed to understand the tendency of actively avoiding challenging information among youth. The findings indicated that demographical factors had little impact on information avoidance. However, education and information literacy self-efficacy was found to have a negative correlation with information avoidance. The study contributes to both the theoretical and practical aspects of the study of information behaviour. On a theoretical level, the study shows the strong presence of information avoidance in information behaviour. On a practical level, it draws attention to information literacy training that could be designed to keep people more aware in sensitive circumstances. Additionally, this study paves a path for future empirical studies on young people’s tendency to avoid information and the possible consequences this behaviour may have on their everyday lives.

While the paper contributes to paving the way for future research on information avoidance, it had its share of limitations as well. For example, the sample is not particularly representative for all the youth in Europe. About half of the sample are users of European Youth Information and Counselling Agency (ERYICA)- Youth Information and Counselling Services. Young people from some countries are more represented than that from the others.The study rather investigated a general notion about information avoidance among youth. We do not know why they avoided information, whether it was due to stigma, rational limit of time, a strategy to handle information overload or another reason(s). The items measuring information avoidance were formulated generally to enable generalization across contexts. A more precise formulation, such as relating the items to specific contexts, like studies or health, would likely have rendered a more precise result and potentially more variation among respondents. Moreover, the quantitative analysis tools applied in this study i.e. Linear regression is still based on correlations only. A more qualitative study following this quantitative analysis could enrich the insight farther. The purpose of the survey, however, was to keep the items general as to be able to speak of information avoidance on a general level, rather than in relation to a specific context. This was at the same time the unique contribution of the study, as information avoidance generally has been explored context-specifically, eg. in relation to health.

However, The high prevalence of avoidance, suggests that the phenomena is not trivial and should be further investigated beyond charged situations and approached from a more neutral standpoint as opposed to being regarded as a given negative. The data for this study was extracted from a larger survey conducted on the everyday information behaviour of youth. To keep the questionnaire within a sizeable limit, the number of items was limited in the information avoidance and information literacy constructs. Moreover, the questionnaire was not particularly designed to study the information avoidance propensity but to gather knowledge about the everyday information behaviour of youth and associated challenges. Nevertheless, the study still produces empirical evidence on the influence of education and information literacy on young people’s tendency to avoid information.

The survey on the information behaviour of youth in Europe was a part of Project Youth. Info: Future Youth Information Toolbox funded by the EU’s Erasmus+ programme. We want to especially acknowledge the European Youth Information and Counselling Agency (ERYICA) for distributing the survey throughout their networks.

Muhaimin Karim is a Doctoral Researcher at the department of Information Studies, Åbo Akademi. Muhaimin has focused his research largely on information and media literacy, information behaviour, information service policy design and youth participation. He has worked in the Digital Workplace Information Literacy (DiWil) project, funded by the Academy of Finland (2016–2020) and Future Youth Information Toolbox - Erasmus+ KA. In 2019, he is working in the Erasmus+ project, Innovative Youth Information Service Design and Outreach. He is also working in a project concerning refugees’ information practices on the Nordic and European levels and is one of the initiators of the MaRIS network (Migrant and Refugee Information Studies). His own doctoral dissertation focuses on the information seeking behaviour of the young population and their perception towards e-government information services. Muhaimin has published reports, journal papers, and conference papers during the aforementioned projects.

Gunilla Widén is Professor of Information Studies at Åbo Akademi University. She has lead several large research projects financed by the Academy of Finland investigating key skills in information society as well as various aspects of social media, changing information behaviour and information literacy. The ongoing Academy of Finland project is on the role of information literacy in the digital workplace (funded 2016–2020). Other ongoing projects focus on youth information behaviour, e.g. Erasmus+ KA strategic projects developing and promoting youth information services. Currently, she is also actively involved in developing research networks on refugees’ information practices on the Nordic and European levels (MaRIS, Migrant and Refugee Information Studies).

Jannica Heinström is an Associate Professor in Information Studies at Åbo Akademi University, Finland, and a docent at the University of Borås, Sweden. Jannica’s research has been funded by, among others, the Fulbright Association and the Academy of Finland. Her research seeks to understand psychological aspects of information interaction, particularly the role of personality. Her work includes studies on serendipity, information avoidance and everyday information behaviour.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

|

© the authors, 2019. Last updated: 14 December, 2019 |