published quarterly by the university of borås, sweden

vol. 24 no. 4, December, 2019

Introduction. The purpose of this paper is to provide a conceptual analysis of the knowledge organization of musical arrangements found in notated Western art music.

Analysis. Four areas of arrangements are analysed. Inter-medium arrangements are explored, which are arrangements that transform one musical medium into another. Arrangements which involve changes of difficulty or pitch are discussed, as well as transformations between notation and performance. Arrangements of forms and genres are analysed, including sub-genres such as literal transcriptions, fantasies, virtuosic arrangements and pot-pourris. The function of arrangements is also discussed.

Results. This study introduces additional facets, foci and types of information. These include the development of musical themes as a classification principle, the concept of a performance-arrangement, and the idea of functions specifically associated with transformation. A categorisation is proposed for the various types of form/genre arrangements, which shows blurred boundaries between types. The impact of time on arrangements is demonstrated, and that there is a non-binary division between the original and the arranged.

Conclusions. Two models demonstrate the complexities of musical arrangement, and how information specific to arrangements needs to be considered within music knowledge organization. Furthermore, the results suggest novel ideas about classifying change and transformation more generally.

Western art music contains many acts of musical transformation. The arrangement of one musical work into another work or version of that work asks interesting questions about music information, and presents interesting challenges for musical classification. There are a multitude of different transformations possible: the transformation can happen in the arena of who is playing or singing, it can affect the formal structures of the musical work, or the transformation could even be the purpose of the work. Arrangements have not been studied in depth within musical classification. Yet, arrangements are useful as they yield up concepts not just applicable to the narrow area of classifying musical arrangements, but also introduce new types of music information not hitherto considered, and even question the faceted structure of music. Furthermore, musical arrangements indicate the instability of musical mediums and other types of musical information, so an examination of their classification is also an examination of the classification of change.

The aims of this article are two-fold. First, this article explores how arrangements fit into the general arena of the classification of music. This includes examining musical arrangements within the context of broader, existing models of music classification, as proposed in works such as Lee (2017a) and Lee and Robinson (2018). In addition, this involves exploring what types of musical information are located within the act of, and result of, arrangement. Second, this article also identifies different categories of arrangements, again seeking to place these within a framework of the connections between different types of musical information. This article focuses entirely on a framework of Western Art music, and there is not space to consider other types of music or cultural heritages. However, it is hoped that the results could be compared to other types of music in future research. While the focus of this article is on the conceptual underpinnings of the classification of arrangements, some examples will be drawn from bibliographic classification schemes (and these generally have Western art music as their focus).

The first part of the article introduces the musicological concept of arrangement, including the thorny issue of terminology. Then, the article will consider four broad types of arrangement information, loosely based around three facets. It starts with a common type of arrangement: inter-medium arrangements, where a composition written for one medium (set of instruments and/or voices) is arranged for another. Then, transformations within medium are considered, introducing the idea of performance arrangements, and the concepts of tessitura and difficulty. The next part considers the classification of transformations which move beyond changes in medium alone, and involve the form/genre facet. (Note, that naming and defining facets of music is not straightforward. This article utilises the names of the main facets concluded in the analysis of meta-facets in Lee (2017a), which draws heavily on Elliker (1994). This includes the hybrid facet of form/genre.) This section shows how there is more information being transformed than structural properties alone, and considers the categorization of various types of form/genre arrangements. The next section explores the role of the function facet in arrangements, introducing the idea of a new type of function which is the transformation itself. The article concludes with two models of the classification of arrangements, which draw together the discussions and illustrate the complexities of musical arrangements.

It is important to consider what is meant by the concept of an arrangement. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians’ definition of arrangement (Boyd, 2001) states that an arrangement involves reworking, as well as being highly likely to be accompanied by a change in medium. The broad perimeters for this article are that the following will be termed as arrangements: taking one musical work and transforming it into either another musical work, or another version of the same musical work, where the resulting work/version resides within the realm of Western art music. (The boundaries of what constitutes a musical work are not discussed in this article, and the term work is deliberately used loosely.) This means that meanings of the terms arrangement and transcription which relate to notation (Ellingson, 2014), Jazz (Tucker and Kernfeld, 2016), transforming recorded sound into notation (Seeger 1990), and so on, are not within the scope of this article. It is also important to note that within the history of Western art music, the concept of arrangements and the values ascribed to arrangements have changed over time (Lee, 2017a).

However, even within these broad parameters, two different terms are used, and can sometimes refer to the same thing: arrangement and transcription. From a musicological perspective the terminology of arrangements and transcriptions is neither homogenous nor temporally-stable. Even as early as 1935, Howard-Jones (1935) suggests that there are many different terms for these concepts and that their meanings differ. Boyd (2001) points out that it is not just musicologists who have been inconsistent: what are commonly referred to as Liszt’s piano transcriptions have the word arrangement on some of their title pages. The word transcription in the second edition of The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians from the 1900s (Fuller Maitland, 1910) is assigned to those works where the musical rhythm, melody, and so on, have changed, and the term arrangement (Parry, 1904) to those which change medium only; yet in the latest article for these concepts in the The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Boyd, 2001), it is implied that the meaning of the terms has switched over from those earlier editions.

A brief look at terminology for arrangements and transcriptions within bibliographic classification schemes is also useful. A study of terminology used in 19 bibliographic classification schemes in Lee (2017a) ranging from the late 19th century onwards, revealed that the bibliographic classification schemes echoed the confusion found in musicological writings: some bibliographic schemes use neither term explicitly, and in other schemes both arrangements and transcriptions are used. However, within the study it was found that the term arrangement was more often used than transcription. So, in this article, as we are discussing a gamut of different types of arrangements and transcriptions, we shall follow Sachania’s (1994) example, and use arrangement as the general overreaching term, with use of the term transcription for specific types of arrangement.

A key part of considering the classification of musical arrangements is to think about how the original and the arranged relate to each other. (It is noted that the terms ‘the original’ and ‘the arranged’ are themselves loaded with value; however, as these are the terms used within bibliographic literature, they have been used. The value judgements implied when dealing with musical arrangements are discussed in the next section.) The relationship between the original and the arranged is a question discussed by musicologists, especially the matter of whether a change of musical medium alone changes the musical work. Levinson (1990, p. 87) suggests that a transcription which changes one ‘performance-means structure’ to another, even if the ‘sound structure’ is not altered, will result in a separate musical work. In faceted terms, Levinson is arguing that a new musical work is created by the process of arrangement, even if the only thing which changes between original and arranged is the foci in the musical medium. Not everyone agrees with Levinson, in particular the musicologist Kivy (1993), who directly challenges Levinson’s writings. The arguments settle around whether who is playing and singing – what classificationists would consider to be the foci in the facet of medium – defines the musical work. Kivy (1993) argues against the Platonist view of works being defined by their performers, and therefore considers an original work and its arrangement to be the same musical work.

This discussion is familiar from other areas of Library Science: considering whether something is a new work or not is an important aspect of the IFLA Library Reference Model (LRM) and its forerunner, the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR). In particular, it is interesting to note how discussions about the relationship between the original and the arranged evoke ideas expressed in FRBR-ised terms in the musicological writings of Kivy, Levinson, and others – though the musicological sources consulted are written before the first publication of FRBR in the late 1990s.

Examining bibliographic classification schemes suggests that most choose to classify music with the medium of the arrangement, rather than the original; for instance, The British Catalogue of Music Classification (Coates, 1960), Flexible Classification system of music and literature on music (Pethes, 1967), the 13th and 22nd editions of the Dewey Decimal Classification (Dewey, Fellows and Getchell, 1932; Dewey et al., 2003), and Library of Congress Classification (Library of Congress, 2019), all place medium arrangements with their actual medium rather than the original. So, in terms of the musicological debate between the Levinson and Kivy camps, this aligns with Levinson winning the fight. Dickinson Classification (Dickinson, 1938) provides an intriguing case study, as this scheme has a variety of different citation orders (which it calls combination orders). In fact, one of the biggest differences between the orders in the Dickinson Classification is whether the original or the arranged is prioritised: the arranged medium comes first for the citation orders designed for ‘loan and performance libraries’, and for ‘general or small libraries’, but ‘reference and musicological libraries’ (Dickinson, 1938, pp. 12-14) are assumed to prefer classification by original medium. So, Dickinson (1938) considers the musicologists to be interested in families of musical works, arguably aligning Dickinson with Kivy’s views about arrangements; whereas Dickinson (1938) considers performers to prefer arrangements to be kept with their actual medium, which could be argued elides with Levinson’s view of transcriptions as distinctive compositions.

The final general idea to be discussed concerns the creativity and authorship of arrangements. Keller (1969, p. 25) divides arrangements into ‘somebody else’s, the composer’s own, and nobody’s’. Taking the first two of these first, the question arises as to whether a composer doing an arrangement of their own work, is the same information process as someone else arranging a composition. Furthermore, does the authority of the arrangement – for instance, someone getting explicit permission from the composer to arrange the work versus someone making an arrangement without speaking to the original composer – have any bearing on the arrangement? This highlights questions about the idea of value associated with arrangements. For example, in some musicological discourse arrangements have been considered to be the antithesis of authenticity (Keller, 1969); this positions the arranger and the arrangement as having less value than the composer and the original composition.

The first type of arrangement considered is the transformation of a musical work from one musical medium to a different medium. For example, a musical work that was originally written for violin and piano, where the music is now for flute and piano, would be an inter-medium arrangement. Another example is a work originally appearing for voices and orchestra, arranged to be performed by just a piano. (Note that this section only considers the transformation of medium, with changes to form/genre, melody, rhythm, harmony, and so on, considered in later sections.)

It is useful to consider how inter-medium arrangements are treated in bibliographic classification schemes. Generally, medium arrangement is a type of information which is included in bibliographic classification schemes; for instance, it is found in The Dickinson Classification (1938), 22nd edition of the Dewey Decimal Classification (Dewey et al., 2003), and Library of Congress Classification (Library of Congress, 2019). However, it is not found in shorter schemes; for instance in Ott’s classification scheme (Ott, 1961), and the 6th and 7th editions of Colon Classification (Ranganathan, 1963; Ranganathan and Gopinath, 1987), there are no references to arrangements. We can hypothesise that while arrangements are important enough to appear in some bibliographic classification schemes, when space is short, arrangements are not considered special enough to warrant distinct treatment. This contrasts with other types of medium information, such as the vocal/instrumental division (Lee and Robinson, 2018), which is omnipresent in classifications of medium.

Ubiquity does not equal importance, of course. Another perspective is to consider the position of arrangement information within these schemes. Library of Congress Classification (Library of Congress, 2019) prioritises the information about whether a work is presented in its original medium or not; for instance, works for piano, string orchestra and cello, to name just a few examples, have an important and primary division between ‘original compositions’ and ‘arrangements’ (Library of Congress, 2019). The corollary of this within an enumerative scheme is that works of the same (current) medium and same form/genre would be scattered if one is an original composition and the other is an arrangement. Library of Congress Classification’s layout is unlikely to be a tribute to the value of arrangements; more likely, this could embody the antipathy of some musicologists and musicians to arrangements, and the Library of Congress Classification example shows pure originals needing to be kept away from their impure arrangement cousins.

There are some significant questions about classification embedded within inter-medium arrangements. For example, if a piece of music has a current medium of piano but was originally written for orchestra, the piano version may not even mention the orchestra in textual data within the document. However, in many bibliographic schemes, the original medium (orchestra) is included within the classification for this document, meaning that both the past and present are represented. This is significant: the inter-medium arrangement holds within it a duality of medium information, which also evokes a temporal dimension.

However, this idea of duality of original and arranged can be explored further. There is an implication that in most inter-medium arrangements, a musical work exists in one medium, and is then transformed into another medium at a later date. In other words, there is a sequence of events. However, there are works which do not follow this sequence. For instance, James MacMillan’s All the hills and vales along was written as part of the centenary commemorations of World War I. The piece exists in two mediums: choir, vocal soloists, brass band and five solo string instruments; choir, vocal soloists, brass band and string orchestra. (Note that if these were different works, there is no question that most classification schemes would treat the string orchestra and the five solo string instruments differently from each other.) The publisher’s metadata for the work describes the medium of the string orchestra, followed by the statements that ‘strings can be optionally reduced (1.1.1.1.1)’ (Boosey and Hawkes, 2019) – where (1.1.1.1.1) means 2 violins, 1 viola, 1 cello and 1 double bass. Two world premieres are listed in the vocal score (MacMillan, 2018), with the one for the smaller medium occurring first. This introduces an interesting classification question about which is the original and which is the arranged. A second issue concerns whether in this situation, where a single document such as the full score (in other words, all the players and singers’ music represented together on the page) could be used for either of the two iterations (string orchestra or five individual string players), is even a transformation at all. Therefore, there is a question about whether the dichotomous classification of inter-medium arrangements which see two distinct categories of medium for original and arranged, always holds true.

The MacMillan example leads us towards another type of arrangement: where the basic description of the medium does not change, but there is some sort of intra-medium transformation. While less common than their inter-medium arrangement cousins, the classification of intra-medium arrangements has interesting implications for gaining a fuller understanding of music knowledge organization.

The first idea to be considered is the arrangement as a facilitator of performance, and what this means for the definition of medium information. For example, a performing group staging an opera may decide to exclude a few instruments from their performance for financial reasons. The medium of both the original and the version presented in the performance would both be classified loosely as orchestra, yet the components constituting these orchestras would differ. (Unlike chamber music (see Lee 2017b), most bibliographic classification schemes have sub-facets for the whole group only – for instance, orchestra, band, choir, string orchestra, and so on – rather than the individual instruments or voices which constitute that group.) This asks an interesting question about whether something can be an arrangement if the differences are only found between the notation and the performance. As well as financial reasons, improving the performance quality is another motivator for these types of arrangements. For instance, Ravel’s ‘Sirènes’ from Nocturnes, includes wordless female chorus; this has been arranged by one world-leading choral director, so that instead of individual sections of the choirs singing individual phrases which pass around the choir, the whole choir sings almost continuously. Singers still sing the same melody, rhythm and so on, but the texture has undergone a transformation in order to achieve a better performance. Both the opera orchestra and Ravel examples could be described as intra-medium arrangements, and we could term them performance arrangements. From a classification perspective, performance arrangements question whether the classification of notated music can be used to classify performance, and illuminate the difference between the information contained within notation versus that within sound.

Tessitura, in this particular context, describes how music written for one range of voice – high voice, medium voice, or low voice – is published for the other types. This is related to the pitch of notes and the different ranges of the human voice. For example, a collection of Schubert’s solo songs intended for study and performance will often be published in multiple versions: the categories used for these types of songs are usually high voice, medium voice, and low voice. This particular method of arrangement is called transposition, and involves the intervals between the pitches, the rhythm, the harmony, the accompaniment, the words, and so on, all staying the same, with the only change in the actual pitches of the notes. Everything is moved up or down by the same degree within any individual song, to better suit specific vocal ranges. This introduces a new type of information called tessitura. There is a question about whether this is a sub-facet of medium, and whether it should be accommodated within the selection of voice type as the central unit of medium (see Lee and Robinson 2018), or is a separate facet which sits outside of medium. The argument for the latter is that it does not describe sonority, but instead is more related to pitches of notes and the corresponding changes in key signatures.

It is useful to consider bibliographic classification schemes’ treatment of tessitura. It is folded into general voice mediums in a number of classification schemes. For example, British Catalogue of Music Classification (Coates, 1960) and the 22nd edition of the Dewey Decimal Classification (Dewey et al, 2003) have classes for high voice, middle voice and low voice; these are part of the medium facet and appear near the classes for soprano, alto, and so on. Dickinson Classification (1938) is unusual in having a specific facet for tessitura, which is applied to solo and solo ensemble vocal music. However, it is also part of a general set of facets which are all part of medium. This small selection of examples suggest that tessitura as a part of music information should not be ignored, but should be considered as a unit of information constituting musical medium rather than a separate facet.

Some arrangements are based on the difficulty of the music to sing or play, and usually involve the arrangement of work from the original into an easier version. For example, one of Chopin’s nocturnes for piano solo might be transformed into an easy piano version of the work. The medium (and other aspects) have stayed the same yet a transformation has taken place. We could see this as a type of change of medium, enveloping the change from one texture within the piano part to another. An alternative is to conceive that such arrangements are actually a separate facet: difficulty. Difficulty is a different type of information from who is playing or singing (medium), and could be useful outside of medium. Furthermore, some arrangements change medium and transform into an easy version in one step – for example, music from the Harry Potter films arranged for easy piano – and we could consider this to be a change in both the medium and difficulties facets. However, in terms of actual use in bibliographic classification schemes, difficulty does not appear to be used frequently.

Some arrangements transform structure as well, and would be considered arrangements between one form/genre and another. For example, Sarasate’s Carmen fantasy, takes an opera by Bizet, and transforms it into a work for violin and orchestra. However, the boundaries of such form/genre transformations are nebulous. First, the difference between an arrangement which evokes a new form/genre and one which transforms medium alone is quite blurred. The impact of those trying to define this boundary for knowledge organization purposes is discussed in later sections. Second, there is also a variety of processes and reasons for form/genre transformations to take place. (Note that in this section, most time will be spent discussing piano transcriptions, especially those by the composer Franz Liszt. This is due to the quantity and importance of piano transcriptions, their popularity within the form/genre associated with transcription, and the importance of Liszt’s arrangements.)

So, we now consider this blurred boundary between medium-only arrangements and arrangements which transform other parts of music information. (Note that this discussion takes place in acknowledgement that form/genre as a facet has some connection to medium (Lee, 2017a)). Musicologists and writers about Western art music attempt to distinguish between these two categories. For example, when discussing Liszt’s arrangements for piano, Walker (2001) roughly divides arrangements into what he calls ‘transcriptions’ and ‘paraphrases’, terms Walker says were coined by Liszt. The transcription is ‘_a faithful re-creation of the origina_l’, whereas in the paraphrase, the arranger is ‘free to vary the original and weave his own fantasy around it’ (Walker, 2001). Friedheim (1962, p. 84) uses a similar categorization when discussing Liszt’s compositions, dividing between ‘literal transcriptions’ and ‘paraphrases’. The term literal helps to clarify the difference between the different types of arrangements, but also indicates that the term transcription by itself is not automatically considered to be literal. So, in knowledge organization terms, we could surmise from the musicologists’ categorizations, that there is a characteristic of division which could be named ‘adherence (to the original)’. This is responsible for the categorization of arrangements into (literal) transcriptions which transform medium only, and paraphrases, which transform more than medium alone.

The next step is to consider what quality of the music is varying or adhering from/to the original. Is the variance from the original a change in form/genre or are there other types of music information involved? For instance, we can consider Liszt’s O du mein holder Abendstern, Rezitativ und Romanze aus der Oper Tannhäuser, which is a transcription for piano solo of a recitative and aria from Wagner’s Tannhäuser. Suttoni (1981– note, there are no page numbers to the introduction) describes it as ‘an almost literal transcription’, and with the noted changes being a different key signature and the addition of a small section of music. So, the formal qualities of the piece – for instance, its structure, themes, how those themes develop, and so on – are unchanged. (A musical theme is a nebulous concept with many overlapping meanings (see Drabkin, 2001), but for this article refers to the recognisable melodic material, usually with associated rhythm and sometimes harmony, which would in colloquial terms be called the tunes.) However, its form/genre has changed: in its original (Wagner), its form/genre is a recitative and aria within an opera, but its form/genre transforms into being a transcription (Liszt).

Yet, there are other arrangements where the structure is also transformed between the original and the arranged. For example, we can consider Liszt’s Deux transcriptions d’apres Rossini and his Paraphrase de concert (Rigoletto) . Here, the original structure is not adhered to, and moreover, while individual themes might appear in both the original and the arranged, the overall works differ between the original and the arranged. It is interesting to note that terminology does not necessarily help distinguish those arrangements which closely follow their original from those which do not stay as close; the term transcription can be used to describe either, although titles such as Reverie and Paraphrase are normally reserved for the freer arrangements.

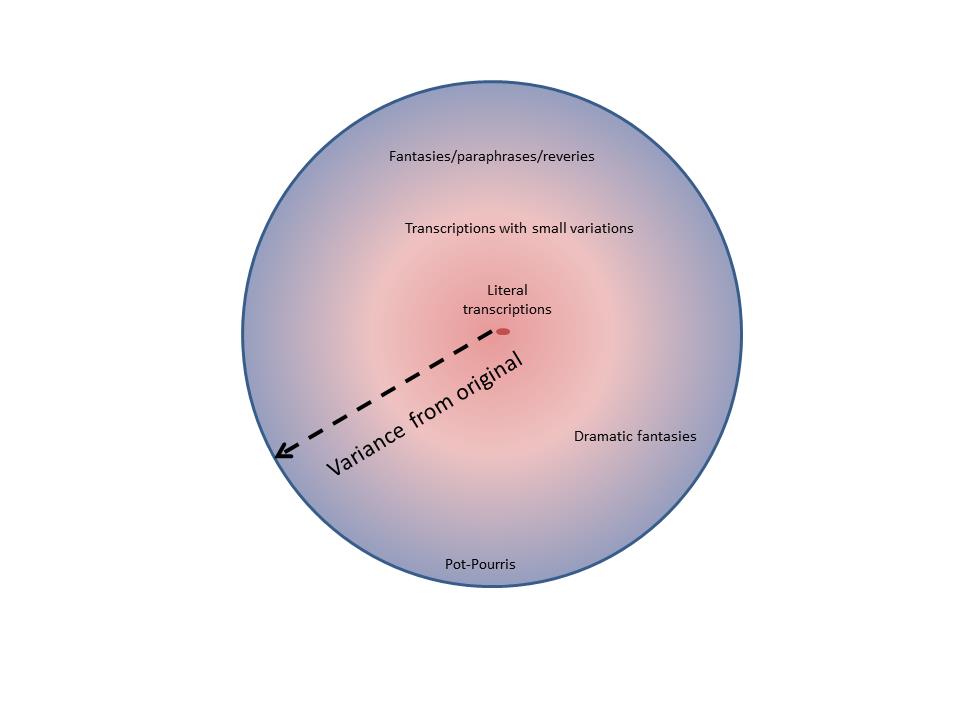

So, we can consider that there are three categories of formal arrangements: so-called literal transcriptions, where form/genre is the only type of information to change other than medium; what we could call literal transcriptions plus, where the formal features are mostly unaltered but small changes take place (and in reality are probably more common than completely literal transcriptions); and, those transformations which take the original themes, but create a new form, and new development of those themes, and so on. These could be considered as a shaded circle which moves gradually from exact replica to considerable changes from the original, and shows how the boundaries between the types of transcription are blurred and difficult to define – see Figure 1. Furthermore, responsibility of the work is another factor. For example, Boyd (1980) discusses a scale of arrangements, which ranges from a simple transcription to a paraphrase; in this model, the responsibility moves from being definitely with the composer, to the paraphrase being considered the responsibility of the arranger. Note its similarity to the FRBR diagram of related works and expressions (Library of Congress, 2012). There is ultimately a value judgement attached to musical arrangements, and part of this is tied up into the relationship between composer and arranger, and the different values attached to the creativity of each party.

Even the free transcriptions seen near the edges of the circle in Figure 1 could be potentially categorised further, based on how the themes are used. Suttoni (1981) identifies a very specific type of fantasy. He gives examples from Liszt’s fantasies based on the operas Norma, Don Giovanni and La Sonnumbula, where the dramatic message of the original is maintained in the transformation to piano transcription (Suttoni, 1981). In music information terms, this means that the dramatic information of the original is the same as in the transcription, but the information relating to the development of themes has been altered. So, we start to see the influence of a third facet, function, which is discussed in later sections. For the purposes of this article, we could term these types of works ‘dramatic paraphrases’ in contrast to the more typical ‘virtuosic paraphrases’ seen so far.

A further type of fantasy can be distinguished: the unofficial genre title of pot-pourri. Like other free arrangements, a pot-pourri takes the themes from a work and then places these melodies together in a composition. They differ from regular fantasies as their focus is on the recitation of many themes with usually no or little repetition, and there is also no development of any of these themes (in other words, the theme appears in its original incarnation and that is the only version of that theme that will appear). For example, Fauré and Messager’s Souvenir de Bayreuth, is a piano duet which utilises the themes from Wagner’s Ring Cycle (a group of 4 operas, spanning around 17 hours in length). The Souvenir de Bayreuth takes themes from these operas and transforms these into a quadrille (a type of dance). The original operas about Norse gods, death, capitalism, love, and the end of the world, is transformed into a lively dance. So, the transformation is not just to medium, form/genre and the development of the melodic material, but also includes a transformation of what we could call character.

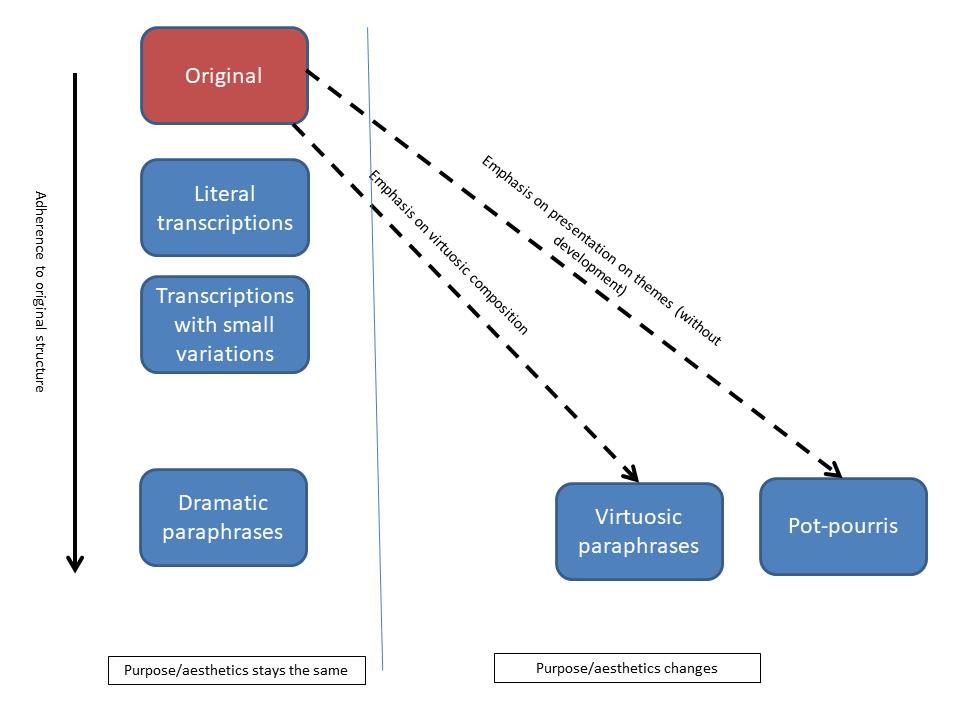

Considering bibliographic classification schemes’ treatment of the different types of transcription forms/genres is quite useful. For example, in the Dickinson Classification, there is a class for ‘Transcriptions, paraphrases, adaptations, pot-pourris’ in the facet which deals with forms/genres (Dickinson, 1938, p. 26). So, Dickinson Classification acknowledges that there are different terms and perhaps different types of transcriptions, yet the scheme considers there to be no classificatory need to distinguish between these. The full categorization of types of inter-form/genre arrangements is shown in Figure 2. Here, the adherence from the original is shown in a vertical line, similar to the radial line in Figure 1. However, the horizontal space is split into a binary division between types of transcriptions which keep the purpose and aesthetics of the original, and those which do not. So, the pot-pourris and virtuosic fantasies become different but equal occupants of the change-in-aesthetics space.

The final facet to consider is function. Unlike the other facets discussed, the transformation of function is not a type of arrangement. In fact, if you only transformed the function of a work and no other information, arguably it would not be considered to be an arrangement at all. However, it will be shown that despite this, function has a key role to play in the transformation of music. (Whether function is a full facet, or occupies some shadowy existence as a quasi-facet is discussed in detail in Lee (2017a)). In Lee (2017a), various axes of functions were discussed, such as dramatic/non-dramatic, which give rise to foci within this facet such as liturgical, dramatic and concert. For instance, a piano fantasy which takes an opera as its source material sees a change in its function from dramatic to concert. However, a piano fantasy based on a symphony, sees no change in its function as its original and arranged function are both concert. There is a function of the original, and a function of the arranged. For some arrangements these are the same, and for other arrangements they differ.

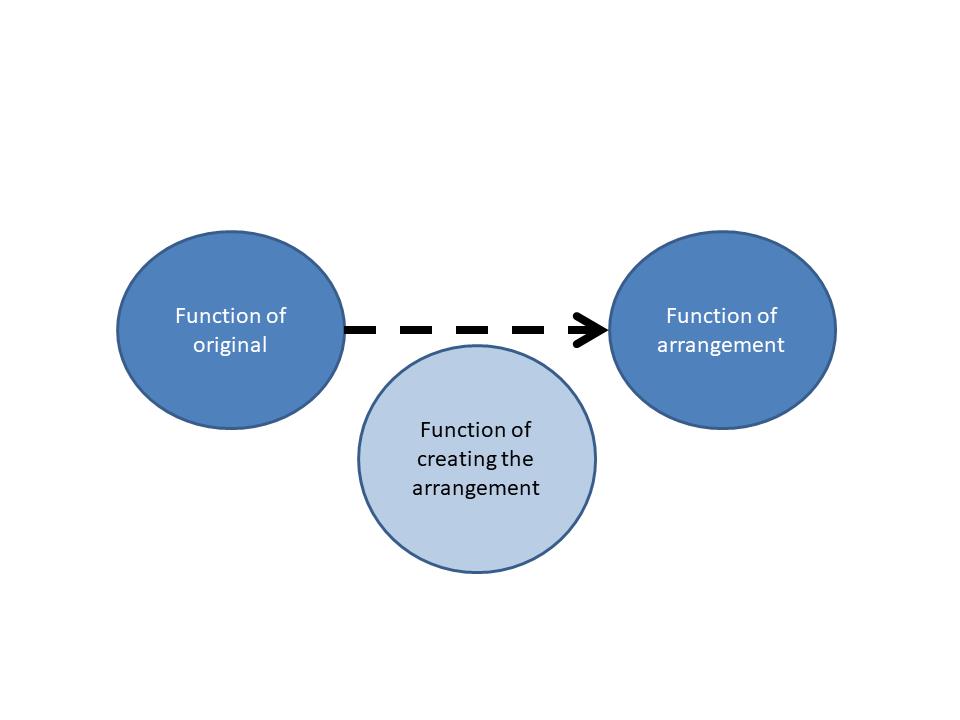

However, it is important to note that the act of making the arrangement also has a function in its own right. For some compositions, the arrangement is made to create a virtuosic work, perhaps for financial reasons. Here, the function of the act of arranging is composition. Promotion of a composer is another possible function. For instance, Suttoni (1981) argues that Liszt’s Wagner transcriptions were been created for the purpose of promoting Wagner’s music. In this example, the function of the original is dramatic, the function of the arranged is domestic or concert, and the function of the transformation is promotion of a composer’s reputation. Another function of arrangements is that they can create music (and performing possibilities) for less ubiquitous instruments or groups of instruments – for example, works arranged from other instruments for tuba in order to extend the repertoire for the tuba. So, arrangement can also have a function of being an enabler of music-making. There are also interesting issues here about who is doing the arrangement, and whether this has an impact on the function of the arrangement.)

Therefore, we can consider the function facet to have three roles in the consideration of arrangements: the function of the original music, the function of the arranged music, and the function of this transformation. These are visualized in Figure 3. The third of these is particularly interesting as it represents a new type of musical information within the function facet, albeit one which is silent within most bibliographic classification schemes. Therefore, this demonstrates why considering the classification of arrangements is valuable, as it helps us to gain a deeper understanding the structure of musical information.

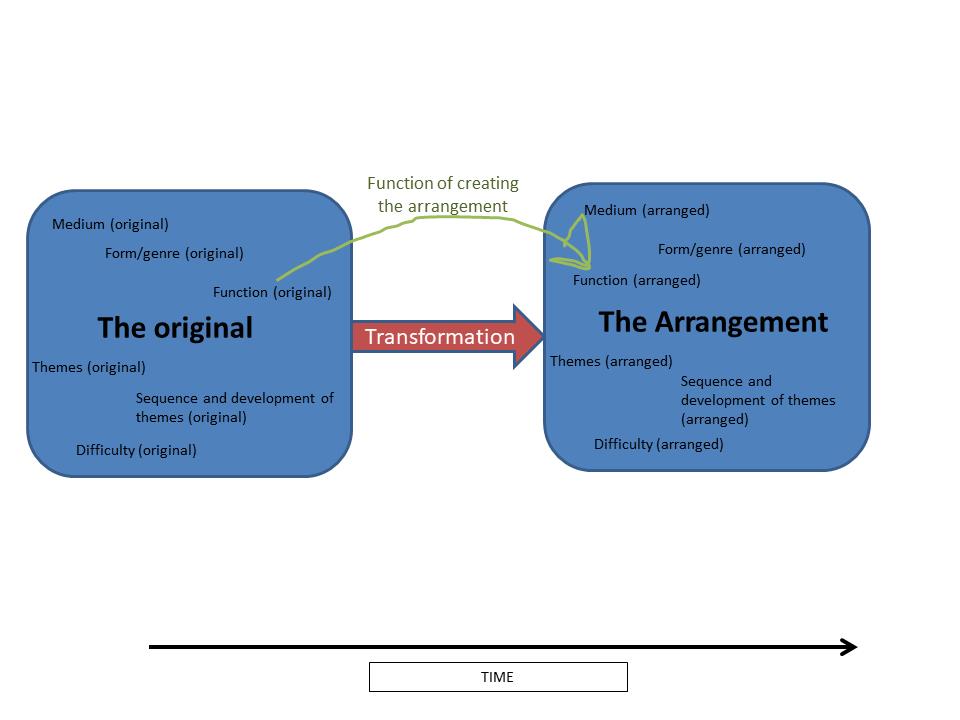

This exploration of the classification of arrangements can be encapsulated in two different models. First, the discussion has illuminated the numerous types of information that can potentially get transformed when a composition is arranged. These are visualised in Figure 4. Each facet of information has a foci for the original (left-hand side of Figure 4), and either the same or a different foci for the arranged (right-hand side of Figure 4). The move from the left to right is the transformation represented by arrangement. The three facets in the top half of the boxes – medium, form/genre and function – are conventional facets of music, as seen in Elliker (1994) and Lee (2017a). We can assume that tessitura and performance-arrangements (see section Transformation of medium) are all covered in the umbrella facet of medium.

The other three types of information are less familiar from music classification discourse. Two are related to the types of issues seen in the section Further categorization within the free transcriptions, when it was shown that there is more to arrangements such as the creation of paraphrases, pot-pourris, and so on, than just the transformation of form/genre. While form/genre covers structural changes and generic expectations, a more detailed approach is needed to understand the different types of arrangements. So, while the types of information – thematic material and sequence or development of thematic material – are not unique to arrangements, their importance to classification of arrangements brings them to the fore. (It is unlikely that they meet the requirements of being considered two separate facets; perhaps they represent two types of information in one facet. This could be considered in future research.) A similar argument could be made for the sixth type of information (difficulty). Difficulty is an outlier for other reasons: for arrangements, it has little meaning for the original work, but can be significant for the arranged. However, there are also non-arrangement scenarios where difficulty could be potentially useful, such as seeking music for specific levels of students.

The specific function of the arrangement process itself is part of neither the original nor the arranged, so this is indicated as a separate arrow in Figure 4. Finally, Figure 4 suggests that the transformation happens over a general axis of time, and that the original and arranged are discrete phenomena. However, as was discussed in the section Blurring of the original and the arranged, there are counterexamples; where would the reduced string version of MacMillan’s All the hills and vales along be placed in Model 1, when it is not clear-cut whether this is an arrangement at all? So, in reality, the timeline is much more muddled than Figure 4 depicts.

In addition to the constituents of the arrangement, the discussion in this article has illuminated some of the factors, or spaces, which arrangements inhabit. To this end, an additional way of considering arrangements is to model the realm of arrangements. This realm has five spaces:

The first of these is covered in Model 1: the facets of music which are impacted by arrangements, including those facets which appear for all types of music and also those which are more prevalent when specifically considering arrangements (such as thematic material, difficulty, and so on). The second factor in the arrangement realm considers how transformation happens over time. This asks questions such as when does the arrangement take place in connection to the composition. The third factor explores the difference between arrangements which are expressed by an additional printed document of the musical work, and those which occur as part of the performance or performance preparation process (whether annotated on the notated music by performers or not). The fourth factor concerns the idea of who is doing the arranging, and how musicological thought might consider arrangements to be a poor cousin to the original composition. We have seen how this value judgement is represented in some bibliographic classification schemes. This brings into the fore ideas involving creatorship (composers and arrangers) and connections to FRBR/LRM ideas about the boundary between a version of an existing work and the new work. The fifth factor considers the information which cannot be contained by existing facets and foci as it is only part of the transformation itself. The purpose of the arrangement is such an example.

Arrangements are a knotty part of the classification of Western art music. They move far beyond a simple movement from one musical medium to another, as they often involve multiple facets and types of information. While the standard facets of medium, form/genre and function are important to the classification of arrangements, this article has also shown how fully understanding the classification of arrangements requires extra types of information such as tessitura, difficulty, themes, and the sequence and development of themes. This article has also discussed the categorization found within certain types of arrangements, arguing that there are actually a variety of form/genre-related arrangements, with difficult-to-define boundaries. Distinguishing between these categories introduces some further types of information not normally considered in music classification, such as adherence to the original, and development of themes. Therefore, we could consider whether, for example, the models of music classification proposed in Lee (2017a), might need extending in future, to add some of these arrangement-specific types of information. This might include utilising extra facets or even types of information associated with the process of arrangement, not just the results of arrangement.

The discussion also introduces some more general ideas within music classification. The introduction of the idea of a performance arrangement within notated music is fascinating, and shows how mode of expression is one important space within the realm of musical arrangements. It is not just what is being arranged which is important, but who is doing the arrangement and when this occurs in the process from composition to performance. The connections between arrangements, authority and value are also highlighted, demonstrating the relationship between ideas in the music domain and within bibliographic music classification.

Finally, studying the classification of musical arrangements is also the study of the classification of change. This study highlights the importance of the idea of time, and how some information is only captured through change itself – for instance, the function of the arrangement. This suggests a more general idea for future knowledge organization research, about consideration of the classification of the dynamic aspects (for instance, the transformation of one work into another) alongside the study of static parts (for instance, the original work and the resulting arrangement). For, what is more important about classifying a musical arrangement than its qualities associated with transformation itself?

Deborah Lee is a researcher and educator in library and information science as well as a practicing librarian. She currently holds the following roles: Joint Acting Head of the Book Library and Senior Cataloguer, Courtauld Institute of Art, and Visiting Lecturer, City, University of London. She can be contacted at deborah.lee.1@city.ac.uk.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

|

© the author, 2019. Last updated: 14 December, 2019 |