Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Ljubljana, Slovenia, June 16-19, 2019

Women in academia: a bibliometric perspective

Tzipi Cooper, Noa Aharony, Judit Bar-Ilan and Sharon Rabin Margalioth.

Introduction. The purpose of the current study is to examine faculty members’ outputs and citations based on their gender and academic rank in the Israeli academia. The study will focus on the connection between research productivity and under-representation of women in academia. To this end, three fields were chosen, each representing a different discipline: Psychology (social sciences), Public Health (STEM), and Linguistics (humanities).

Method. The name, the rank and the gender of the researchers were collected from the researchers’ websites and those of their departments. The number of publications and citations were retrieved from Scopus.

Analysis. Data were analysed quantitatively using Excel and SPSS to highlight the differences between gender by subject, academic rank and collaboration.

Results. Findings reveal that in all three disciplines, the average number of publications for females is lower than that of males. As academic promotion is associated with a researcher’s number of publications, we can understand why female representation in higher academic ranks in Israel is low.

Conclusions. It is not enough to look at gender disparity overall, but rather to consider it in each field, because each discipline has unique features and differs from others.

Introduction

In recent decades, numerous studies regarding the role, status and experience of women in academia were conducted. These studies suggested that although there is an increase in the number of educated women, it is still difficult for women to advance in academia and achieve senior positions (Aiston and Jung, 2015).

The literature presents four explanations for gender barriers in the academy. The first is discrimination caused by negative stereotypes against female researchers inside and outside academic institutions. Second, there is the under-representation of females related to women coping with work-family balance (Ceci and Williams, 2011). Third, the implicit bias of academic decision makers who prefer to promote males over females (Moss-Racusin , Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham, and Handelsman, 2012). Fourth, females have a lower research productivity compared to males (Mairesse and Pezzoni, 2015; Mayer and Rathmann, 2018; Nielsen, 2016). The current research will focus on the fourth barrier.

Research productivity and women

Research productivity is the most important measure for promoting university faculty. It illustrates the commitment of researchers to scientific activity and is used as a tool for institutional and personal evaluation of the excellence of faculty members and their suitability for promotion (Mayer and Rathmann, 2018; Ramsden, 1994).

One of the main indicators for measuring researchers’ productivity is the number of their publications, especially those published in international journals (Litwin, 2014; Nygaard and Bahgat, 2018; Shin, Jung, Postiglione, and Azman, 2014). Generally, research productivity is examined by bibliometric measures that include the source of publications, citations or both (Nygaard and Bahgat, 2018).

Various studies have used bibliometric analyses to examine the status of women in academia. Past studies suggested that women published less than men (Abramo, D’Angelo, and Caprasecca, 2009; Cole, 1979; Cole and Zuckerman, 1984; Fish and Gibbons, 1989; Fox, 2005; Helmreich, Spence, Beane, Lucker, and Matthews, 1980; Hesli and Lee, 2011; Long, 1992; Reskin, 1978).These findings reinforced the notion that women’s lower academic ranks was a result of inferior scientific productivity.

Some bibliometric analyses have explored several disciplines and have provided evidence of a gender gap presenting women researchers as less productive than men. Weisshaar (2017), who examined computer science, sociology and English, suggested that there are some differences between men and women concerning productivity measures. In sociology, women publish fewer articles in high-ranked journals. In both computer science and sociology, women publish fewer journal articles overall, and receive fewer citations per publication than men, on average. In computer science, women publish less as a last author or as a single author than men. In the English faculty, women publish in high-ranked journals more than men.

Further, Beaudry and Larivière (2016) explored the health and science fields, and revealed that women publish and are cited less often than men. Moreover, when most of the authors are men the publications are cited more than when most of the authors are women.

Referring to bibliometric analyses that explored one discipline. König, Fell, Kellnhofer, and Schui (2015) investigated the psychology field and found several gender differences: a smaller number of publications, fewer citations and first authorships by women, and slight differences between the two genders for the average JIF (Journal Impact Factor) per researcher, in favour of men.

Other researchers (Carter, Smith, and Osteen, 2017) have explored the field of social work, which is dominated by women. They compared male and female h-index averages for all academic levels: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Full Professor. They found that the average female h-index is lower in all faculty ranks, but they were most notable between men and women at the level of Full Professor. This finding can be explained by the "Matthew effect", a term that describes how well-known scientists get more credit than less famous researchers, even if their work is similar (Toren, 2005; Merton, 1988).

However, other studies have reported small or no gender differences in publication rates (D’Amico and Di Giovanni, 2000; Gupta, Kumar and Aggarwal, 1999; Joy, 2006; Lemoine, 1992; Long and Fox, 1995; Maass and Casotti, 2000; Li, Latib, Kwong, Zinzuwadia, and Cowan, 2007; Mathtech Inc., 1999; Mauleo´n and Bordons, 2006; Sonnert and Holton, 1995; Ward and Grant, 1998; Xie and Shauman, 1998). Moreover, studies from 2015 and 2016 showed that there has been an improvement in women’s publications over the years (Mairesse and Pezzoni, 2015; Nielsen, 2016). Hence, as there are different views concerning women’s research productivity, one of the goals of the current study is to explore the relationship between research productivity and under-representation of women in Israeli academia in three different disciplines: Psychology (social science), Public Health (STEM) and Linguistics (humanities).

Another issue associated with research productivity is research collaboration. In recent decades, collaboration among authors has played an increasingly important role in research promotion and impact. The intensity of collaboration varies and depends on the scientific field. In general, in interdisciplinary fields, researchers tend to collaborate more than in fields that are more self-contained (Abramo, D’Angelo and Di Costa, 2009).

Gender difference in collaboration is essential to explore because of the increase in research collaboration in groups and networks (Leydesdorff and Wagner, 2008), as well as in interdisciplinary research (Lee and Bozeman, 2005). Fell and Köning (2016) explored reasons for gender differences in collaboration and suggested that on one hand women are generally more agreeable than men, a personality characteristic that might lead to more networking. Moreover, women outperform men in tests of emotional intelligence, another trait that might contribute to collaboration. On the other hand, women traditionally take care of their children, an issue that is time consuming and may limit their participation in different networks. Further, there are findings suggesting that women get less than optimal mentoring compared to men and, as a result, their socialization into scientific communities is not comparable.

Various studies explored if there are gender differences in collaboration. Findings revealed that women collaborate less than men, and that they publish more single authored works (Boschini and Sjögren, 2007; Fox, 2001; Jadidi, Karimi, Lietz, and Wagner, 2018; Nielsen, 2016; Zettler, Cardwell, and Craig, 2017). Women are also less inclined to take part in longstanding research collaboration that are associated with high-impact science impact (Jadidi et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2016). However, other researchers (Fell and Köning, 2016), in a study of industrial-organizational psychologists, reported that female researchers were more engaged in scientific collaborations than men. Abramo, D’Angelo, and Murgia (2013) found that female researchers in Italy collaborate more than male researchers.

Concerning international research collaboration, some studies suggest that women on average have less international collaboration than men. Frehill and Zippel (2010) reported that among holders of Ph.D. degrees in the United States, men have more international collaborations than women. Further, a bibliometric analysis by Elsevier (2017) found that women collaborate internationally less than men. However, the She Figures report by the European Commission (2015), found only small differences in this regard.

Based on the literature, it is important to analyze international research collaboration as it affects researchers’ productivity and scientific impact (Abramo et al., 2009, Abramo, D’Angelo, and Solazzi, 2011; Adams, 2012; Fox, 2018; Kyvik and Reymert 2017; Larivière, Ni, Gingras, Cronin and Sugimoto, 2013). Thus, another goal of the present study is to explore the relationships between the level of Israeli women’s collaborations and the under-representation of women at the Israeli academia in the three different disciplines noted above.

Women in Israeli academia

The representation of women in university staff in Israel is low compared to European countries (Goldschmidt, 2012). In 2015/2016, 55% of Israeli university faculty members with the rank of Lecturer were women, and only 17% were Full Professors (Lerrer and Abger, 2018).

The process of recruitment and promotion of faculty members in Israeli academia is not homogeneous. Each institution may decide autonomously the requirements for recruitment and promotion. However, the most important factor for promotion is publications.

Very few studies in Israel have examined faculty members’ outputs and citations. A study that examined h-index differences between men and women in social work (social sciences), a discipline that has a higher representation of women, found a lower h-index average for women at the levels of Lecturer and Full Professor, and a reverse trend at the levels of Senior Lecturer and Associate Professor (Panisch, Smith, Carter, and Osteen , 2017).

Various studies found a gender gap in which women researchers were less productive than men. Some focused on one discipline and others on cases from one country: Spanish psychologists (Barrios, Villarroya, and Borrego, 2013), Swedish physicians (Fridner, Norell, Åkesson, Sendén, Løvseth, and Schenck-Gustafsson, 2015), library and information scientists (Penas and Willett, 2006), German cardiologists (Bohm, Papoutsis, Gottwik, and Ukena, 2015), social psychologists (Cikara, Rudman, and Fiske, 2012), and German medical researchers (Kretschmer, Kundra, Beaver, and Kretschmer, 2012). The current study examines faculty members’ outputs and citations by gender and academic rank in Israeli academia. The study considers the connection between research productivity and under-representation of women in academia. To this end, three fields were chosen, each representing a different discipline: Psychology (social sciences), Public Health (STEM), and Linguistics (humanities). The research questions are:

- Do women in Israel publish and are cited less in all the disciplines tested?

- Is the average number of publications and citations the same in all academic ranks in Israel (Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, Associate Professor and Full Professor)?

- Do men collaborate more than women in Israel?

Methods

The first step was gathering data and entailed collecting the names, gender, and academic rank of all senior faculty members of the three disciplines in Israel. This was done by extracting information from departmental websites. Thus, if members of other departments published in the selected fields, they were not included.

The next step was to collect all the publications of the selected researchers. Some of them had full publication lists on their websites, some only selected publications and some had no publication list at all. Thus, data were gathered from the bibliometric database Scopus, both to receive the list of publications indexed by Scopus and the number of citations these publications received by the time of data collection. Publication data were collected during July and August of 2015 and citation data in March 2019 to allow enough time for all publications to have citations. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS. Results are presented by discipline.

Results

Note that in our analyses, we used full counting (i.e., if researcher A collaborated with researcher B in our dataset, the publication is assigned as 1 to both). In order to examine whether there are differences between men and women regarding the number of publications, citations, and authors in the three disciplines, a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was performed. The Kruskal-Wallis test did not reveal any significant difference between men and women in the three disciplines (Psychology, Public Health and Linguistics).

Psychology

The first subject we examined was Psychology. This discipline included 136 researchers as of 2015. The number of faculty members by academic rank, publications, and citations are displayed in Table 1.

| # researchers | # citations | # publications | Ave # of citations per publication | Ave. # of publications per researcher | Ave. # of citations per researcher | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| **Female** | **59** | **101,854** | **2,115** | **48.16** | **35.85** | **1,726.34** |

| Lecturer | 10 | 4,737 | 141 | 33.60 | 14.10 | 473.70 |

| Senior lecturer | 19 | 12,800 | 362 | 35.36 | 19.05 | 673.68 |

| Associate professor | 14 | 30,596 | 657 | 46.57 | 46.93 | 2,185.43 |

| Full Professor | 16 | 53,721 | 955 | 56.25 | 59.69 | 3,357.56 |

| **Male** | **77** | **185,048** | **3,684** | **50.23** | **47.84** | **2,403.22** |

| Lecturer | 4 | 2,272 | 66 | 34.42 | 16.50 | 568.00 |

| Senior lecturer | 22 | 21,521 | 513 | 41.95 | 23.32 | 978.23 |

| Associate professor | 17 | 42,713 | 737 | 57.96 | 43.35 | 2,512.53 |

| Full Professor | 34 | 118,542 | 2,368 | 50.06 | 69.65 | 3,486.53 |

| **Total** | **136** | **286,902** | **5,799** | **49.47** | **42.64** | **2,109.57** |

Psychology in Israel is a majority male subject, as can be seen by the number of male faculty members versus female faculty members. Overall, men publish more and receive more citations per publication than women. A male Full Professor published the article with highest number of citations.

Next, we examined collaboration patterns of Psychology researchers. Only 5.34% of the female publications and 6.35% of the male publications were single-authored. The most frequent number of co-authors for both women and for men was 4 (30% and 31%, respectively). A male Associate Professor had the highest number of collaborators on a paper (946).

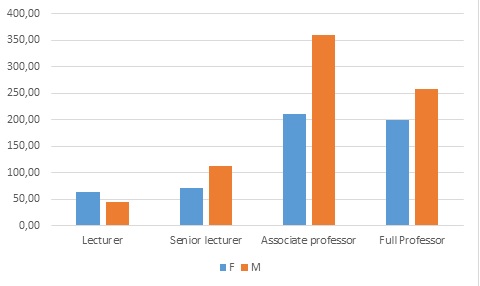

Further investigation relating to collaboration patterns of Psychology researchers revealed that when calculating the total number of authors (in publications that had more than one author), divided by the total number of publications (in which more than one author participated), there were differences between men and women. At the first academic rank, Lecturer, women collaborate on average more than men, whereas in later stages of a career (Senior Lecturer, Associate Professor, and Full Professor) men tend to collaborate more than women. Data are presented in Figure 1.

The second subject area was Public Health with 64 researchers, most (55%) being females. Even though there are less men, the average number of publications per male researchers (regardless of rank) is considerably higher than for women—female Lecturers, Senior Lecturers, and Full Professors have a higher average number of publications and citations. The number of faculty members in each rank, and the number of publications and citations are given in Table 2.

| # researchers | # citations | # publications | Avg. # of citations per publication | Avg. # of publications per researcher | Avg. # of citations per researcher | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| **Female** | **35** | **90,607** | **2,737** | **33.10** | **78.20** | **2,588.77** |

| Lecturer | 8 | 8,956 | 264 | 33.92 | 33.00 | 1,119.50 |

| Senior lecturer | 9 | 15,407 | 419 | 36.77 | 46.56 | 1,711.89 |

| Associate professor | 10 | 19,434 | 809 | 24.02 | 80.90 | 1,943.40 |

| Full Professor | 8 | 46,810 | 1,245 | 37.60 | 155.63 | 5,851.25 |

| **Male** | **29** | **87,476** | **2,738** | **31.95** | **94.41** | **3016.41** |

| Lecturer | 5 | 1,451 | 87 | 16.68 | 17.40 | 290.20 |

| Senior lecturer | 3 | 2,232 | 93 | 24.00 | 31.00 | 744.00 |

| Associate professor | 10 | 31,314 | 952 | 32.89 | 95.20 | 3,131.40 |

| Full Professor | 11 | 52,479 | 1,606 | 32.68 | 146.00 | 4,770.82 |

| **Total** | **64** | **178,083** | **5,475** | **32.53** | **85.55** | **2,782.55** |

Examining the collaboration patterns in Public Health revealed that in this subject multi-authorship is the norm, as less than 5% of the publications are single authored, and there is one publication with 720 co-authors. Male Senior Lecturers participated most in large projects having 11 to 44 authors.

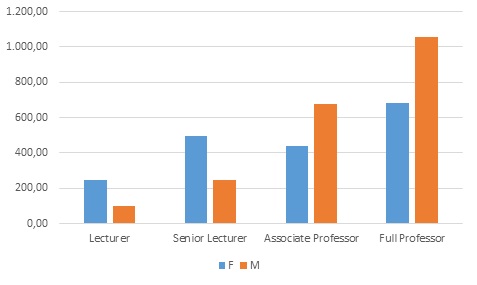

When calculating the total number of authors (in publications that had more than one author) divided by the total number of publications (in which more than one author participated), there were differences between men and women. We found that women collaborate on average more than men at the two first academic ranks (Lecturer, and Senior Lecturer). However, in the higher academic ranks, male Associate Professors and Full Professors tend to collaborate more than women. Data are presented in Figure 2.

Linguistics

We found 30 researchers in Linguistics in Israel. Their gender, academic rank, the number of publications and citations are displayed in Table 3. A female Full Professor published the article with the highest number of citations.

| # researchers | # citations | # publications | Avg. # of citations per publication | Avg. # of publications per researcher | Avg. # of citations per researcher | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| **Female** | **19** | **6,964** | **210** | **33.16** | **11.05** | **366.53** |

| Lecturer | 4 | 216 | 18 | 12.00 | 4.50 | 54.00 |

| Senior lecturer | 6 | 1,692 | 50 | 33.84 | 8.33 | 282.00 |

| Associate professor | 2 | 671 | 26 | 25.81 | 13.00 | 335.50 |

| Full Professor | 7 | 4,386 | 116 | 37.80 | 16.57 | 626.57 |

| **Male** | **11** | **1,730** | **129** | **13.41** | **11.73** | **157.27** |

| Lecturer | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Senior lecturer | 3 | 133 | 14 | 9.50 | 4.67 | 44.33 |

| Associate professor | 3 | 635 | 56 | 11.34 | 18.67 | 211.67 |

| Full Professor | 4 | 960 | 57 | 16.84 | 14.25 | 240.00 |

| **Total** | **30** | **8,694** | **339** | **26.44** | **11.30** | **298.80** |

Linguistics in Israel seems to be dominated by females: there are more faculty members overall, more faculty members in each rank (except for Associate Professor), more publications and citations than for male researchers. Male Associate Professors are again an exception. It is interesting to note that the average number of publications by females is slightly lower than that of males, but the average number of citations is much higher. Further, the article with the highest number of citations was published by a female Full Professor.

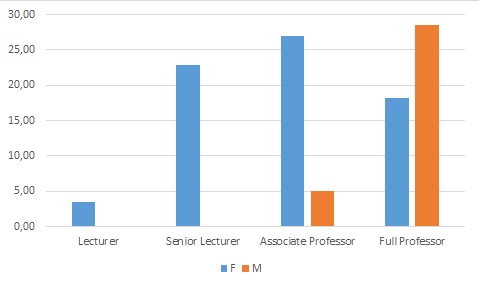

We were also interested in the collaboration patterns of males versus females in Linguistics. Both men and women seem to prefer to be single authors: out of the 210 female authored publications 108 (51%) were single authors. For males, out of 129 publications, 90 were single authored (70%). When calculating the total number of authors (in publications that had more than one author) divided by the total number of publications (in which more than one author participated), there were differences between men and women. Women collaborate on average more than men in the first three academic ranks (Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, and Associate Professor), while in the Full Professor rank a reverse trend was observed. Data are presented in Figure 3.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine faculty members’ outputs and citations regarding their gender and academic rank in Israeli academia in three different fields: Psychology (Social Sciences), Public Health (STEM), and Linguistics (Humanities). The study focused on the connection between research productivity and under-representation of women in academia. In order to explore research questions 1 and 2, we focused on findings that appeared on the fifth and sixth columns in Tables 1, 2, and 3, as these columns present the average number of publications and citations per researcher. The Kruskal-Wallis test did not reveal any significant difference between men and women in the three disciplines.

However, we see that overall, in all three disciplines, females’ average number of publications is lower than males’ average number of publications. This finding echoes previous ones that indicated that women published less than men (Cole, 1979; Cole and Zuckerman, 1984; Fish and Gibbons, 1989; Helmreich et al., 1980; Long, 1992; Reskin, 1978). We can associate these findings with the under-representation of women in Israeli academia, because the main parameter for recruitment and advancement in academia is the number of publications. The first research question examined whether women publish less often and are cited less frequently in the three chosen fields. This question relates to females versus males regardless of academic rank. Results reveal that in Psychology, men publish more than women, and they are cited more often than women. The data indicate that Psychology is a male dominated subject, at least in Israel.

Addressing Public Health, women publish less than men, and women are cited fewer times than men on average. Regarding Linguistics, women publish slightly less on average than men. However, they receive many more citations than men. The results concerning Psychology and Public Health duplicate previous studies that showed that female academics in the social sciences in Germany, Finland and Hong Kong publish significantly less than male colleagues in the same field (Aiston and Jung, 2015). However, our findings contrast those of Frandsen, Jacobsen, Lynn, Brixen, and Onsager (2015), who found very little difference in the number of citations and publications between men and women.

The second research question explored whether the average number of publications and citations is the same in all academic ranks (Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, Associate Professor and Full Professor).

Investigating the average number of publications and citations in Psychology showed that only in the Associate Professor rank women have a higher average number of publications than men. For all other academic ranks, men publish more than women and are cited more frequently than women. These findings agree with a previous study (König et al., 2015) that showed that in the specialization of industrial/organizational Psychology, females publish less, and have fewer citations on average than males. The article with the highest number of citations was published by a male Full Professor. These findings agree with our previous results, showing that in Psychology, men publish more than women, and that they are more cited than women. These findings may strengthen the assumption that Psychology is a male dominated field.

Considering the average number of publications and citations in Public Health, we found that Israeli female Lecturers, Senior Lecturers, and Full Professors have more publications and citations on average than males. However, these findings contrast a previous study (Beaudry and Larivière, 2016) conducted in the health and science fields, which found that women published more times, but were cited less than men. However, these researchers did not present their results by academic rank.

When examining the number of publications in Linguistics, we can see that in three of the academic ranks (Lecturer, Senior Lecturer and Full Professor), women have more publications than men. Concerning the number of citations, women have more than men, and the article with the highest number of citations was published by a female Full Professor. These findings can be compared with previous results that men have more publications than women (Fox, 2005; Hesli and Lee, 2011; Rorstad and Aksnes, 2015). However, Fox (2005) studied STEM fields, which are not relevant to Linguistics. Hesli and Lee (2011) considered Political Science and found that women publish less. Rorstad and Asknes (2015) studied Norwegian researchers as a whole and did not concentrate on specific fields. Our findings in Linguistics and Public Health were similar to those of van Arensbergen, van der Weijden and van der Besselaar (2012), who found that younger female researchers (Lecturers and Senior Lecturers in our case) outperform males in terms of average number of publications per researcher in the Social Sciences in the Netherlands.

The third research question investigated whether male Israeli researchers collaborate more than women. In Psychology, most of the publications were not single-authored, and the most frequent number of co-authors for both women and for men was 4. This may indicate that there are no differences between Israeli male and female researchers concerning collaboration in Psychology.

In the area of Public Health, it seems that multiple authors are the norm, as less than 5% of the publications are single authored, and there is one publication with 720 co-authors. Further, male Senior Lecturers participate most in large projects (i.e., those having 11 to 44 authors). This finding illustrates that most of the Israeli researchers in Public Health collaborate, and that males collaborate more than females. This finding about males’ level of collaboration in Public Health was already mentioned in past research (Nielsen, 2016; Zeng et al., 2016). Further, the finding that in Psychology and Public Health, females collaborate less than males may be explained by a previous study (Uhly, Visser and Zippel, 2017) that suggested that the cause for female’s low collaboration is marriage, which prevents them from collaboration at the international level.

Unlike Psychology and Public Health, in Linguistics, both men and women seem to prefer being single authors. This result may be associated with a former study (Abramo, D’Angelo, and Di Costa, 2009) that suggested that, in general, researchers tend to collaborate more in interdisciplinary fields than in fields that do not have this characteristic. An interesting note that stems from our study is that when there are more females in the discipline (as was true of Linguistics and Public Health), we see more collaborations among different academic ranks: Lecturer, Senior Lecturer and Associate Professor (in Linguistics), and Lecturer, and Senior Lecturer (in Public Health).

Conclusions and Limitations

The purpose of this study was to examine faculty members’ outputs and citations based on their gender and academic rank in Israeli academia, using three different fields: Psychology (Social Sciences), Public Health (STEM), and Linguistics (Humanities). Findings revealed that in all three disciplines, females’ average number of publications was lower than that of males’. Thus, as academic promotion is associated with researchers’ number of publications, we can understand why females’ representation in higher ranks in Israel is low.

According to our findings, two of the three fields studied (Linguistics, and Public Health), were predominantly female as to the number of faculty members. Only one field (Psychology) was male dominated. It was not surprising to find out that Linguistics is female dominated, as it belongs to the humanities. Psychology was shown to be male dominated, as this finding replicates previous studies in this area. However, it was interesting to see that Public Health, that belongs to a medical discipline, is female dominated in terms of number of staff members. Another major conclusion is that it is not enough to look at gender disparity at a general level, but it is important to consider it in each field separately, as each discipline has unique features and differs from others.

The current study has some limitations: The samples are small, as Israel is a small country. Also, the study contains only publications indexed by Scopus. Moreover, as the study was conducted only in Israel, its results are specific to Israeli academia. We recommend that a future study include researchers from other countries as well.

Acknowledgements

The Israeli Ministry of Science and Technology funded the study. The results are part of Tzipi Cooper’s doctoral project, advised by Professor Aharony.

About the authors

Tzipi Cooper works at Department of Information Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. She can be contacted at zico64@gmail.com.

Noa Aharony is professor at Department of Information Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. She can be contacted at noa.aharony@biu.ac.il.

Judit Bar-Ilan was professor at Department of Information Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. She passed away in July 2019

Sharon Rabin Margalioth is professor at Harry Radzyner Law School, IDC Herzliya, Israel. She can be contacted at srabin@idc.ac.il.

References

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. & Caprasecca, A. (2009). Gender differences in research productivity: a bibliometric analysis of the Italian academic system. Scientometrics, 79 (3), 517–539.

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A. & Di Costa, F. (2009). Research collaboration and productivity: is there correlation?. Higher Education, 57 (2), 155–171.

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A. & Murgia, G. (2013). Gender differences in research collaboration. Journal of Informetrics, 7 (4), 811–822.

- Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A. & Solazzi, M. (2011). The relationship between scientists’ research performance and the degree of internationalization of their research. Scientometrics, 86 (3), 629–643.

- Adams, J. (2012). Collaborations: the rise of research networks. Nature, 490 (7420), 335–6.

- Aiston, S. J. & Jung, J. (2015). Women academics and research productivity: an international comparison. Gender and Education, 27 (3), 205–220.

- Barrios, M., Villarroya, A. & Borrego, Á. (2013). Scientific production in psychology: a gender analysis. Scientometrics, 95 (1), 15–23. Barrett, L. & Barrett, P. (2011). Women and academic workloads: career slow lane or cul-de-sac? Higher education, 61 (2), 141–155.

- Beaudry, C. & Larivière, V. (2016). Which gender gap? Factors affecting researchers’ scientific impact in science and medicine. Research Policy, 45 (9), 1790–1817.

- Bohm, M., Papoutsis, K., Gottwik, M. & Ukena, C. (2015). Publication performance of women compared to men in German cardiology. International journal of cardiology, 181, 267–269.

- Boschini, A. & Sjögren, A. (2007). Is team formation gender neutral? Evidence from coauthorship patterns. Journal of Labor Economics, 25 (2), 325–365.

- Carter, T. E., Smith, T. E. & Osteen, P. J. (2017). Gender comparisons of social work faculty using h-index scores. Scientometrics, 111 (3), 1547–1557.

- Ceci, S. J. & Williams, W. M. (2011). Understanding current causes of women’s under-representation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108 (8), 3157–3162.

- Cikara, M., Rudman, L. & Fiske, S. (2012). Dearth by a thousand cuts? Accounting for gender differences in top‐ranked publication rates in social psychology. Journal of Social Issues, 68 (2), 263–285.

- Cole, J. R. (1979). Fair science: women in scientific community. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Cole, J. R. & Zuckerman, H. (1984). The productivity puzzle: persistence and change in patterns of publication of men and women in scientists. In P. Maier & M. W. Steinkamp (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (Vol. 2, pp. 217–258). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

- D’Amico, R. & Di Giovanni, M. A. (2000). Pubblicazioni in riviste di psicologia: Un’analisi di genere. [Publications in Italian psychology journals: a gender analysis]. Bollettino di Psicologia Applicata, 232, 39–47. Elsevier (2017). Gender in the global research landscape. Retrieved from https://www.elsevier.com/research–intelligence/ campaigns/gender-17 European Commission (2015). _She figures 2015. _Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/research/swafs/pdf/pub_gender_equality/she_figures_2015-final.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2ZAakm5)

- Fell, C. B. & König, C. J. (2016). Is there a gender difference in scientific collaboration? A scientometric examination of co-authorships among industrial–organizational psychologists. Scientometrics, 108 (1), 113–141.

- Fish, M. & Gibbons, J. D. (1989). A comparison of the publications of female and male economists. The Journal of Economic Education, 20 (1), 93–105. Fox, M. F. (2001). Women, science, and academia: graduate education and careers. Gender & Society, 15 (5), 654–666.

- Fox, M. F. (2005). Gender, family characteristics, and publication productivity among scientists. Social Studies of Science, 35 (1), 131–150.

- Fox, M. F. (2018). Women in global science: advancing academic careers through international collaboration. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

- Frandsen, T. F., Jacobsen, R. H., Wallin, J. A., Brixen, K. & Ousager, J. (2015). Gender differences in scientific performance: a bibliometric matching analysis of Danish health sciences graduates. Journal of Informetrics, 9 (4), 1007–1017.

- Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 97 (1), 49–69

- Fridner, A., Norell, A., Åkesson, G., Sendén, M. G., Løvseth, L. T. & Schenck-Gustafsson, K. (2015). Possible reasons why female physicians publish fewer scientific articles than male physicians–a cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 15 (1), 67–84.

- Goldschmidt, R. (2012). Data on women in academia (in Hebrew). Retrieved from www.knesset.gov.il/committees/heb/material/data/mada2012-03-06.doc

- Gupta, B., Kumar, S. & Aggarwal, B. (1999). A comparision of productivity of male and female scientists of CSIR. Scientometrics, 45 (2), 269–289.

- Helmreich, R. L., Spence, J. T., Beane, W. E., Lucker, G. W. & Matthews, K. A. (1980). Making it in academic psychology: demographic and personality correlates of attainment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39 (5), 896–908.

- Hesli, V. L. & Lee, J. M. (2011). Faculty research productivity: why do some of our colleagues publish more than others?. PS: Political Science & Politics, 44 (2), 393–408.

- Jadidi, M., Karimi, F., Lietz, H. & Wagner, C. (2018). Gender disparities in science? Dropout, productivity, collaborations and success of male and female computer scientists. Advances in Complex Systems, 21 (03n04), 1750011.

- Joy, S. (2006). What should I be doing, and where are they doing it? Scholarly productivity of academic psychologists. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 346–364.

- König, C. J., Fell, C. B., Kellnhofer, L. & Schui, G. (2015). Are there gender differences among researchers from industrial/organizational psychology? Scientometrics, 105 (3), 1931–1952. Kretschmer, H., Kundra, R., Beaver, D. & Kretschmer, T. (2012). Gender bias in journals of gender studies. Scientometrics, 93 (1), 135–150.

- Kyvik, S. & Reymert, I. (2017). Research collaboration in groups and networks: differences across academic fields. Scientometrics, 113 (2), 951–967.

- Lemoine, W. (1992). Frequency distribution of research papers and patents according to sex: the case of CSIR, India. Scientometrics, 24, 449–469.

- Nature News, 504 (7479), 211–213.

- Lerrer M. & Abgar, I, A. (2018). _Women in academia _(in Hebrew). Retrieved from https://fs.knesset.gov.il/globaldocs/MMM/64a5fee7-6462-e811-80dd-00155d0a0b8d/2_64a5fee7-6462-e811-80dd-00155d0a0b8d_11_10507.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2M3oCZa)

- Lee, S. & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social Studies of Science, 35 (5), 673–702.

- Leydesdorff, L. & Wagner, C. S. (2008). International collaboration in science and the formation of a core group. Journal of Informetrics, 2 (4), 317–325.

- Li, S. F., Latib, N., Kwong, A., Zinzuwadia, S. & Cowan, E. (2007). Gender trends in emergency medicine publications. Academic Emergency Medicine, 14 (12), 1194–1196.

- Litwin, J. (2014). Who’s getting the biggest research bang for the buck. Studies in Higher Education, 39 (5), 771–785.

- Long, J. S. (1992). Measure of sex differences in scientific productivity. Social Forces, 71, 159– 178.

- Long, J. S. & Fox, M. F. (1995). Scientific careers: universalism and particularism. Annual Review of Sociology, 21 (1), 45–71.

- Maass, A. & Casotti, P. (2000). Gender gaps in EAESP: numerical distribution and scientific productivity of women and men. European Bulletin of Social Psychology, 12 (2), 14–31.

- Mairesse, J. & Pezzoni, M. (2015). Does gender affect scientific productivity?. Revue Économique, 66 (1), 65–113.

- Mathtech Inc. (1999). The effects of graduate support mechanisms on early career outcomes. Arlington, VA.

- Mauleo´n, E. & Bordons, M. (2006). Productivity, impact and publication habits by gender in the area of materials science. Scientometrics, 66, 199–218

- Mayer, S. J. & Rathmann, J. M. (2018). How does research productivity relate to gender? Analyzing gender differences for multiple publication dimensions. Scientometrics, 117 (3), 1663–1693.

- Merton, R. K. (1988). The Matthew effect in science, II: cumulative advantage and the symbolism of intellectual property. Isis, 79 (4), 606–623.

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J. & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109 (41), 16474–16479.

- Nielsen, M. W. (2016). Gender inequality and research performance: moving beyond individual-meritocratic explanations of academic advancement. Studies in Higher Education, 41 (11), 2044–2060.

- Nygaard, L. P. & Bahgat, K. (2018). What’s in a number? How (and why) measuring research productivity in different ways changes the gender gap. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 32, 67–79.

- Panisch, L. S., Smith, T. E., Carter, T. E. & Osteen, P. J. (2017). Gender comparisons of Israeli social work faculty using h-index scores. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 9 (3), 439–447.

- Penas, C.S. & Willett, P. (2006). Brief communication: gender differences in publication and citation counts librarianship information science research. >Journal of Information Science, 32 (5), 480–485.

- Sonnert, G. & Holton, G. (1995). Gender differences in science careers: the Project Access study. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press

- Ramsden, P. (1994). Describing and explaining research productivity. Higher Education, 28 (2), 207–226.

- Reskin, B. F. (1978). Scientific productivity, sex, and location in the institution of science. American Journal of Sociology, 83 (5), 1235–1243.

- Rorstad, K. & Aksnes, D. W. (2015). Publication rate expressed by age, gender and academic position–A large-scale analysis of Norwegian academic staff. Journal of Informetrics, 9 (2), 317–333.

- Shin, J. C., Jung, J., Postiglione, G. A. & Azman, N. (2014). Research productivity of returnees from study abroad in Korea, Hong Kong, and Malaysia. Minerva, 52 (4), 467–487.

- Toren, N. (2005). Women in Israeli academia: images, numbers, discrimination (in Hebrew). Ramot, Tel Aviv.

- Uhly, K. M., Visser, L. M. & Zippel, K. S. (2017). Gendered patterns in international research collaborations in academia. Studies in Higher Education, 42 (4), 760–782.

- Van Arensbergen, P., van der Weijden, I. & van den Besselaar, P. (2012). Gender differences in scientific productivity: a persisting phenomenon? Scientometrics, 93 (3), 857–868.

- Ward, K. B. & Grant, L. (1998). Gender and academic publishing. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: handbook of theory and research (Vol. 11, pp. 172–212). New York: Agathon.

- Weisshaar, K. (2017). Publish and perish? An assessment of gender gaps in promotion to tenure in Academia. Social Forces, 96 (2), 529–560.

- Xie, Y. & Shauman, K. A. (1998). Sex differences in research productivity: new evidence about an old puzzle. American Sociological Review, 847–870.

- Zeng, X. H. T., Duch, J., Sales-Pardo, M., Moreira, J. A., Radicchi, F., Ribeiro, H. V., Amaral, L. A. N. (2016). Differences in collaboration patterns across discipline, career stage, and gender. PLoS Biology, 14 (11), e1002573.

- Zettler, H. R., Cardwell, S. M. & Craig, J. M. (2017). The gendering effects of co-authorship in criminology and criminal justice research. Criminal Justice Studies, 30(1), 30–44.