Towards a taxonomy for designing serendipity in personalized news feeds

Urbano Reviglio.

Introduction. Given the interdisciplinary and elusive nature of serendipity, different yet related disciplines have interpreted and employed the concept of serendipity in different ways.

Method. The article is a theoretical and interdisciplinary investigation on the research history of serendipity in digital environments. It seeks to map the conceptual space of ‘artificial serendipity’ and its research to arrive at conceptual distinctions. This is done through carrying out an interdisciplinary literature review informed by Floridi’s philosophy of information.

Analysis. It is discussed the development of artificial serendipity introducing fruitful distinctions between hyper-personalized serendipity, pseudo-personalized serendipity, ‘individual serendipity’ (filter bubble-related serendipity), ‘political serendipity’ (echo chambers-related serendipity) and ‘sensational serendipity’.

Results. In order to increase serendipity designers and engineers -particularly in the context of social media content personalization- should recognize the nuances of designing for serendipity and accuracy and, therefore, from an ethical standpoint, attempt to balance hyper-personalized and pseudo-personalized recommendations – as they are competing design goals – even by stimulating users’ information seeking by design and through discovery tools.

Conclusion. The conceptual dimensions explored in the article represent an initial attempt to develop the study of serendipity in digital environments so as to avoid conceptual overlaps, prevent misconceptions and, eventually, trigger further technical and ethical discussions

Introduction

Serendipity is the epitome of the Internet and digital environments. Everyday Internet users accidentally discover surprising and meaningful information that change their current task, their own opinions, their beliefs, and even their lives. Social media, search engines, news aggregators, social bookmarking such as folksonomy and, more generally, browsing and hyperlinks are powerful sources of coming across serendipitous information. Yet, serendipity is not only a widespread by-product of digital environments but it can be intentionally inscribed into algorithms (e.g. collaborative filtering) and designed through affordances (e.g. trending topics and hashtags) to ultimately increase serendipitous encounters and information discoverability. In the last decade, the phenomenon of serendipity in digital environments, or ‘artificial serendipity’, is indeed receiving increasing attention.

Traditionally, most of the studies on serendipity focused on scientific discovery and innovation studies (Merton and Barber, 2004; Foster and Ellis, 2014). In recent years, however, serendipity is being researched in information studies, design theory, digital libraries and learning theories (Race and Makri 2016; McCay-Peet and Toms 2017). On the one hand, this focus represents the obvious need to effectively manage information overload in the digital era to satisfy users whereas, on the other hand, it provides insights, techniques and tools to tackle the risks of filter bubbles and echo chambers, namely the redundant consumption of consonant information both at the individual and at the group level, particularly in social media’s highly personalized environments. As such, serendipity is acknowledged as a desirable ethical design principle for search engines, recommender systems (RSs) and, more generally, social network sites (Reviglio, 2019). Research also investigates serendipity as a capability of self-learning – also referred to as accidental learning (Kop, 2012) – and explores how and why individuals obtain information opportunistically, rather than purposively, and what are the effects of such behaviour for individuals and public opinion (Yadamsuren and Erdelez, 2016).

Given its interdisciplinary and unpredictable nature, serendipity is rather difficult to research and define. Different definitions in fact assign different weights to personal and environmental factors, between individual responsibility and lucky chance, and approach the phenomenon from different perspectives (McCay- Peet and Toms 2017). For example, information behaviour research approach serendipity as a quality of someone, research relating to recommender systems and search engines as a quality of an event or something, and information science and human-computer interaction (HCI) as an experience or a process. There is indeed a lack of consensus on the meaning, the approaches and the functions of artificial serendipity. This not only raises technical issues but also an ethical ones, given that any recommendation is a nudging, and any nudging embeds values.

The article is a theoretical and interdisciplinary investigation of the development of serendipity and its study in digital environments. Serendipity is indeed deeply involved in various sub-domains of information science, such as information retrieval and information literacy, knowledge management and knowledge acquisition. As such, it will be analyzed from the perspective of the philosophy of information (Floridi, 2002; 2004), conceivable as the unifying theory of information science (Tomic, 2010). The aim is to shed light on the nuances of engineering artificial serendipity and to stimulate further discussions. The paper is organized as follows; firstly, it is provided an historical overview of the concept of serendipity with a specific focus on the evolution of so-called ‘artificial serendipity’, that is, computer-generated serendipity. An up-to-date review of the debate is thus provided. Secondly, the article elaborates a conceptual analysis of diverse interpretations of artificial serendipity, ultimately making distinctions between pseudo-personalized serendipity and hyper-personalized serendipity, and between ‘individual serendipity’ (filter bubbles-related) and ‘political serendipity’ (echo chambers-related). Finally, we discuss how such clarifications are significant to develop the study of serendipity in digital environments so as to avoid conceptual overlaps, prevent misconceptions and eventually, trigger further technical and ethical discussions.

What is Serendipity?

Let us start by clarifying the phenomenon of interest. Serendipity is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the faculty or phenomenon of finding valuable or agreeable things not sought for”. As such, it can be a route to new knowledge, problem-solving, belief change and, more generally, creativity and innovation. It has received attention in several fields from sociology of science to epistemology, from psychology and innovation studies to library research and computer science. It is no surprise that there is no consensus on its meaning. Serendipity is indeed relatively a neologism with no equivalent in languages other than English. The word famously originated from Horace Walpole in 1754, inspired by the Persian fairy tale “The Three Princes of Serendip”. This English version of the story originated from ‘Peregrinaggio di tre giovani figliuoli del re di Serendippo’ published by Michele Tramezzino in Venice in 1557 (Austin, 2003). Tramezzino claimed to have heard the story from Christophero Armeno, who had translated the Persian fairy tale into Italian from Book One of Amir Khusrau’s Hasht-Bihisht of 1302. However, the word did not appear in print until 1833 and in any of the abridged dictionaries until 1951 (Merton and Barber 2006). Largely ignored since then, it gained popularity from mid-1900s when it was applied to various breakthroughs in scientific research, until voted as “UK’s favourite word” in 2000 (Rubin et al. 2011).

As serendipity became famous, “the vogue word became a vague word” (Merton and Barber, 2006). There is, in particular, a significant misconception; serendipity is often incorrectly referred to as the “happy accident”, thus as an experience related to coincidence, luck and providence and, as a result, it is likely to consider it an ill-defined buzzword (Makri 2014). The dilution of its meaning challenges its application in research (McCay-Peet and Toms 2017). In fact, serendipitous discoveries can be perceived as accidentals but they are usually the result of environmental affordances and design as well as individual’s observation and previous knowledge. A ‘serendipitous proclivity’ has to be considered also as a capability (de Rond 2014), intended as being capable of making use of the opportunities that the environment provides (Sen 2005).

The ability to extract knowledge serendipitously covers all areas of human activity, including ‘science, technology, art, and daily life’ (van Andel 1994). According to Merton and Barber (2006), serendipity is one of the main forces that has steered the progress of science. The role of serendipity on epistemology of science is indeed well-established. Yet, also accidental encountering is an integral part of everyday information behaviour (Erdelez 2004), also called information encountering (Erdelez, 1997) or micro-serendipity (Bogers and Björneborn 2013). Even though serendipity studies have suggested that serendipity is a rare, elusive phenomenon, in today’s information societies serendipity is more common even though users do not always recognize it.

More recently, the first handbooks on how to research (McCay- Peet and Toms 2017) and cultivate serendipity in digital environments (Race and Makri 2016; Bjorneborn 2017; de Melo 2018) provided the ground for novel studies. These studies suggest how the tension between the need to manage both the quantity and quality of information has been a key driver of research. They show how serendipity in digital environments can be reduced and cultivated through design, affordances and RSs and acknowledge its positive outcomes and ethical value (Reviglio, 2019). Furthermore, it is researched the role of serendipitous news consumption online (so-called Incidental Exposure to Online News) for the formation of individual and public opinion (Yadamsuren and Erdelez 2016). Media researchers have largely ignored such phenomenon for a long time. In recent years, however, more studies started to explore how individuals obtain information accidentally and opportunistically.

A Brief History of Artificial Serendipity

Serendipitous discovery has been a research topic for more than one hundred years. Fathers of cybernetics recognized the value of a necessary (but not sufficient) element of serendipity: surprise, which operates as a cognitive/emotional reaction to serendipitous encounters (Rubin et al. 2011). In mathematical terms, Shannon (1948) argued that information is proportional to its deviation from expectation. In other words, the amount of information is a measure of surprise. The question of whether computers are able to ‘take us by surprise’ was instead famously raised by Alan Turing (1950). Despite theoretical discussions, the potential of computers to trigger serendipity was already apparent. A famous example is the 1968’s Cybernetic Serendipity art exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in which the relationship between technology and creativity was explored.

The focus on serendipity then shifted in the realm of library and information science, with the first article by Bernier (1960). Early work on serendipity were done in relation to browsing Online Public Access Catalogs (O’Connor, 1988). Functionality for supporting serendipitous discovery included browsable search indexes and similar article citation retrieval (Rice, 1988). In more general terms, however, Van Andel (1994) argued a common argument: “computer program cannot foresee or operationalize the unforeseen and can thus not improvise ('imprevu' = 'unforeseen'). It cannot be surprised or astonished, and has no sense for humor, curiosity or oddity” (…) The very moment I can plan or programme ‘serendipity’ cannot be called serendipity anymore.” Skepticism about programming ‘true’ serendipity is in fact widespread (Krotoski 2011; Carr 2016). Once you create an engine to produce serendipity, one may claim, you destroy its essence. If serendipity could be controlled, then an event is no longer serendipitous, but predictable or reproducible. Yet, it remains possible to cultivate serendipity (Race and Makri, 2016) and it is exactly its unpredictability in which lies its valuable capacity of increasing information diversity (Reviglio, 2019). Moreover, the concept of serendipity in digital environments – also defined as artificial serendipity, that is, not only more generally computer-generated serendipity, but also whenever an agent is able to create the necessary conditions for serendipity to occur (de Melo, 2018) – has been reframed with another valence, focusing on both its preconditions and its individual experience (Erdelez, 1999). Instead, natural serendipity—meaning the serendipity that occurs naturally in the world—is absolutely unpredictable, as the number of factors and variables that create it are impossible (at least as of now), to calculate (de Melo, 2018). As such, there are various degrees of serendipitous encounters – it is a continuum to cover the entire spectrum of different degrees of surprise and meaningfulness.

With the advent of the Internet and the consequent change in the production and consumption of information, the concept of serendipity became more debated. It was indeed acknowledged that computer search tended to provide answers to questions facilitating purpose-driven information seeking instead of opportunistic and accidental ones – typical of browsing printed information. Still, without search engines the journey on the web was initially intended as discovering what was out there—accidentally—not on finding specific content (Hendler and Hugill, 2013). This led Gup (1997) to wonder about “The End of Serendipity”, in particular the most ‘random’ and proactively yet accidentally sought one. Moreover, any procedure to select and prioritize information for users – especially in newspapers, and more generally in traditional media – to some extent recognizes and seeks to solve in a beneficial manner the tension between a generalized relevance—what individuals are expected to want—and serendipity—what individuals may like—due to personalization in digital environments this balance shifted from serendipity to relevance (Thurman, 2011). In the passage from an ink economy to a link economy and from a “professional filter” to a “social filter” (Tewksbury, 2003), this ideal tension became more significant: the potential for relevant and personalized content increased as well as for serendipitous ones.

As personalization improved its accuracy there has been an increasing recognition of the value of serendipity. Media theorist Steven Johnsons (2006) described the Internet as ‘the greatest serendipity engine in the history of culture’. Yet, with the development of the web 2.0 few platforms took over the market and began to steer worldwide information consumption. Thus, concerns took over on hopes. Meckel (2011) made an appeal to ‘save serendipity’ as a fundamental experience for individual progress. Identities can indeed be undermined by profiling algorithms that are stuck in the past, impeding the ‘aspirational self’. Profiling technologies that enable personalization in fact cannot produce or detect a sense of self but they influence a person’s sense of self (Hildebrandt, 2009). Hildebrandt (2017) argues that such ‘incomputable nature of the self’ should be somehow protected. In fact, not only no personal profile can ever entirely identify an individual, but there are always many—and sometimes radically different—ways of computing the same person. In this respect, the value of serendipity is of paramount importance as there is a trade-off between algorithmic accuracy and serendipity (Kotkov et al, 2016). Its design also acknowledges the natural identity reductionism, the potential hedonistic redundancy and more generally, the exploitation of individuals’ vulnerabilities that personalization practices and design choices can unfold and, therefore, it represents the endeavour to overcome them (Reviglio, 2019).

Despite several challenges that the design of serendipity faces, there is a recognition that it has the potential to prevent the threats of filter bubbles and echo chambers (Yadamsuren and Erdelez 2016; McCay-Peet and Toms, 2017). Even if evidences on their negative consequences are rare and the concepts are ill-defined and serve more as metaphors, all the models of democracy consider these intertwined phenomena problematic for particular different reasons (Bozdag and Van den Hoven, 2015). As such, the design for serendipity attempts to preserve the likelihood of encountering information one may (not) like—in opposition to individuals’ hedonism and platforms’ pursuit of profit— to avoid that past behaviours pre-determine and excessively strengthen future ones, and to balance the information diet. Ultimately, designing for serendipity helps the discovery process. Zuckerman (2008; 2013) is a prominent advocator of serendipity, especially concerning the phenomenon of cyber-balkanization. For example, how the development of a cosmopolitan culture may be limited due to georeferenced algorithms. He expected that serendipity tools would become as important as search engines and social media are nowadays. Indeed, there have been over time more and more attempts to pursue serendipity as a design goal, among them, for information retrieval (e.g. Campos and Figuereido, 2003), for social media (e.g. Burkell et al., 2012), for music discovery (e.g. Zhang et al., 2012), for idea generation to contribute to interdisciplinary research (Darbella et al., 2014) business and ICT development (e.g. Saini and Khurana, 2013), for information behavior strategies to enhance online discovery, in everyday searches (e.g. Buchem, 2011) or in academic scholarly research (e.g. Maloney and Conrad, 2016).

Nowadays Internet mainstream services such as Netflix, Amazon, Google Now and Spotify certainly provide serendipitous recommendations. Yet, they tend to exploit convergent systems—as the capacity to discover the right thing at the right time, to cater to the user’s perceived intentions, interests, tastes—rather than divergent systems—as the increasing of information diversity in order to expand user’s horizons and to help uncover surprising discovery (de Melo, 2018). An example of the former narrative is Google CEO Eric Schmidt (2006) which envisioned a future where people and technology come together to create a serendipity engine “where you don’t even have to type” (2006). Internet, however, can be ever more serendipitous, especially in social networking sites and to the extent in which information explorability is effectively sustained. Under the current business model, personalized relevance and quantity outstrip serendipity and quality, providing only an ‘illusion of serendipity’ (Erdelez and Jahnke, 2018). The capacity to control curation and to navigate information filters is indeed rather limited (Harambam et al. 2018). As such, there are two major competing conceptions of designing (for) serendipity: one is based on convergent systems and the other on divergent systems. These actually represent two diverse routes to trigger serendipitous encounters. How do we draw the line between the two, if any?

Exploring the Concept of Artificial Serendipity

Given the interdisciplinary and elusive nature of serendipity, different yet related disciplines have interpreted and employed the concept of artificial serendipity in different ways. For this reason, it will be now attempted an initial deconstruction of such concept in the context of personalization based on an interdisciplinary literature review.

At a theoretical level, the pursuit for artificial serendipity underpins several intertwined assumptions and values (Reviglio, 2019); acknowledging the positive value of designing for serendipity in fact means that despite advancements in computing, the outcomes of algorithms will always be actually unpredictable. There is no perfect personalization indeed (call it ‘hyper-personalization’) as algorithms will be never able to fully understand the complexity of a human being. Even individuals may not always be sure of what they actually want and prefer. As such, personalization of news feeds ought not to approach any accuracy optimization and try to preserve a degree of ‘random encounters’ and items less profile-based. Eventually, on the one hand, the design for serendipity helps to appraise the natural limitations of personalization – even at the cost of users’ engagement and hedonism – while, on the other hand, it invites us to accept the multiplicity of our identities and the need for a balanced and diverse diet. In any case users ought to be responsibly empowered with an effective information discovery agency and not to fully delegate information seeking to an often privatized and naturally biased algorithmic information filtering.

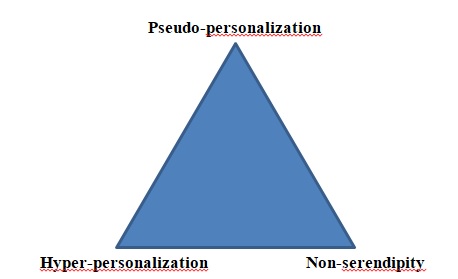

At a practical level, there are two primary conceptions that require to be highlighted; on the one hand, active serendipity, which occurs both when designers provide serendipitous tools by design and when users proactively seek information and eventually experience serendipity with these. On the other hand, passive serendipity, when engineers inscribe serendipity into algorithms and when user passively and opportunistically receives potentially serendipitous information. These intertwined conceptualizations share another paramount distinction: hyper-personalized serendipity and pseudo-personalized serendipity which ideally differ for the extent to which they rely on individual profiling and, therefore, on their (presumed) accuracy. Furthermore, we identify individual and political serendipity, which respectively aim to increase the exposure to new ideas and potentially new interests, outside one’s filter bubble, and facts, views and arguments, outside one’s echo chambers. These can be both hyper- and pseudo-personalized.

All these different interpretations of serendipity need a more detailed analysis. In fact, they emerged in literature but they may be difficult to grasp as they are often implicitly intended and their meanings often overlap. Therefore, we now propose a preliminary taxonomy of the main interpretations of artificial serendipity according to different design processes and disciplines’ perspectives.

Hyper-personalized serendipity

Hyper-personalization is generally intended as the use of data to provide more personalized and targeted products, services and content. Hyper-personalized serendipity can thus be intended as the attempt to recommend serendipitous items based on an individual profile. This endeavor could follow the principle of kairos (traditionally kairos is a Greek divinity, personification of the “opportune moment”) – one of the principles of captology, the study of computer as persuasive technologies – that refers to the ability to provide the right content, at the right person in the right moment (Fogg et al. 2002). Hyper-personalized recommendations could in fact be timely, useful, surprising and persuasive, yet not necessarily serendipitous. When this is the case, hyper-personalized serendipity could represent what has been termed as ‘serendipity on a plate’ (Makri et al, 2014), namely highly personalized and passive serendipity. It is the conception of serendipity more akin to research on RSs, marketing and nudging practices (Kotkov et al, 2016). Thus, it is primarily driven by the principles of delegation and efficiency. To some extent, it is indeed a necessary feature of RSs and other information systems. In theory, however, encounter only (or clearly mostly) hyper-personalized information, particularly in personalized news feeds, may only create an illusion of serendipity (Erdelez and Jahnke, 2018) and become detrimental both to individuals and societies at large (Reviglio, 2019). Yet, hyper-personalization is also an ideal tool for news organizations to regain control of the news distribution process and reconnect with audiences.

Hyper-personalization is the paradigm of convergent systems. To give an example, one watches a movie at the cinema and then stumbles upon a review of that particular movie online. One may experience this as serendipitous, and the content related to the review may well be indeed. Its serendipitousness may, however, be limited. These recommendations may be less unexpected by users – they can realize they depend on data surveillance – and, therefore, it becomes naturally less serendipitous while, relatedly, it is problematic from a privacy perspective. Moreover, the conflicting interests of platforms that provide such services are questionable; in fact, the natural feeling of privacy loss can undermine trust over the system (Bol et al., 2018). For this reason, it is clear how the deployment of hyper-personalized serendipity may be even limited in order to preserve profitable surveillance practices. Also, it might be employed in a crafty and deceitful way. For example, by creating compulsion loops that are actually found in a wide range of social media. These, in fact, may work via a “variable-rate reinforcement,” in which rewards are delivered in an unpredictable fashion. Thus, hyper-personalized content could be purposefully offered among uninteresting content in a way that increases engagement (intended as the more scrolled posts, the more ads sold and thus revenues). In this case it is fake or sensational serendipity (as further explained). Moreover, user’s privacy preferences can constitute informative metadata which the system could use to make sensitive inferences about the user and ultimately influence such exposure to hyper-personalized content. Despite speculations, the business model of mainstream social media is nevertheless based on surveillance practices (Zuboff, 2015), and individuals are even risking of not getting a deserved pay-off, that is, high quality personalized information.

Sensational Serendipity

Sensational serendipity is a sub-group of hyper-personalized serendipity. Yet, while hyper-personalization may also imply serendipitous encounters, sensational serendipity is surprising but does not lead to any valuable insight. It is merely fake, ephemeral and/or even addictive. It usually exploits users’ inferred vulnerabilities regardless of the quality of information. Sensational serendipity is indeed inherently persuasive and, at times, manipulative. It drives click-bait, misinformation and disinformation. Further research on the techniques to design it and the individual reactions to it is certainly needed to better understand it.

Pseudo-personalized serendipity

Pseudo-personalization refers to all those recommendations that are statistically unlikely – or less likely – that may lead to more unexpected serendipitous encounters. To some extent, it is already an implicit by-product of personalization practices as they are indeed inherently probabilistic. This, however, depends on the extent of the likelihood of a recommendation to be liked (recommendation’s accuracy). On the one hand, pseudo-personalization might be highly unlikely to be liked (low accuracy of recommendation) – or at times even be random or – at least – random in an exploratory way. On the other hand, it might be more accurate, that intersects a user’s profile but, still, less accurately than hyper-personalization. This design attempt is significant to trigger serendipitous encounters because in order to make sense of chance information exposure “information must resonate with some prior knowledge, interest, or experience for the user” (Helberger, 2011). It is thus paramount in regards to the ethics of serendipity. The values that serendipity underpins – such as chance, diversity, media pluralism, autonomy and interdisciplinarity – are indeed particularly advocated by theorists (Abbott, 2008; Stiegler, 2017; Reviglio, 2019). In fact, in opposition to hyper-personalization, engineered pseudo-personalization attempts to provide the most unexpected serendipity – as being less probable and less predictable – it thus represents a more hazardous attempt to design for serendipity, particularly from an economic perspective (i.e. engagement and thus profit may be threatened). Also, it is time-consuming, risk-taking, sometimes distracting and frustrating. In order to properly sustain pseudo-personalized serendipity, information discoverability –the possibility to find and access content with a specific quality– is also fundamental, along with the semi-randomizability of information filtering. In the case of active serendipity, its role becomes even more significant; it could in fact provide the possibility to subtract from any potentially (biased or excessively pre-determined) algorithmic curation and be able to be exposed to more casual, diverse and, eventually, serendipitous content. The main aim of pseudo-personalization is to actually overcome the potential determinism implicit in profiling – which can result in redundancy and limited pool of information – as well as platforms’ information selection power. Since long this limitation of recommender systems was acknowledged as the “over-specialization problem”, that is, “when the system can only recommend items scoring highly against a user’s profile, the user is restricted to seeing items similar to those already rated (Balabanović and Shoham, 1997).

Individual Serendipity

‘Individual serendipity’ is related to the filter bubble problem and, thus, particularly related to the concept of personal identity, particularly affected by ICTs that are indeed technology of construction of the self (Floridi 2011). It is thus intended as the design attempt to expose users to information that intersects a user digital profile, so that an individual can discover new ideas and interests, indeed outside one’s filter bubble. As such, this conception is the most akin to the concept of ‘content diversity’ by design (Helberger, 2011) and it implies a degree of generalization and diversification of information selection. It can be sustained through active serendipity that means, generally speaking, to provide serendipitous affordances (Gibson 2014). Similarly, discoverability is fundamental to sustain cultural diversity (Burri, 2019). In this context, a significant design choice might be to afford more profiles per user. The management and access to multiple filtering can in fact nudge users to subtract from the determined path offered by algorithms (Bozdag and Timmermans 2011). This conception of serendipity also sustains what Hildebrandt (2017) defines as ‘agonistic machine learning’, that is, demanding companies or governments that base decisions on machine learning to explore and enable alternative ways of datafying and modelling the same event, person or action.

Pseudo-personalization may actually be not particularly problematic as long as the system adapts to the individual serendipitous disposition – the more diversity you consume the more diverse the information selected. There are, however, two main issues to consider. On the one hand, growing ‘epistemic inequality’ (Lynch 2016). Certain privileged group of users, that have higher (digital) literacy, are effectively able to reach a good balance between relevance and serendipity, and the recommender systems would indeed adapt to their serendipitous proclivity. Instead, a larger group of users risk to be exposed only to a minimum, qualitatively inferior range of information. On the other hand, there is an asymmetry between first and second order preferences. What if a user would ideally prefer to be more open and curious while in practice actually prefers her or his comfort zone if this is (more often subtly) offered? In other words, individual serendipity also attempts to fill the mismatch between the necessity for the aspirational self to uncover and the intrinsic identity reductionism of profiling. Finally, one may feel to enjoy a diverse media diet while it is ignoring the actual potential diversity and serendipity the Internet may offer. Therefore, it is essential to provide ‘serendipity agency’, namely the capability to use tools to control and be aware of the production and one’s own consumption of information. Such endeavor embraces ‘pro-ethical design’ or so-called “tolerant paternalism” (Floridi, 2016) that aims to modify the level of abstraction of the choice architecture by educating users to make their own critical choices.

Political Serendipity

Political serendipity concerns the risks of echo-chambers and, thus, it is particularly related to certain democratic principles, especially media pluralism. It is intended not only as a metaphor but also as the proactive attempt to expose users to content that is politically challenging in order to balance user’s political news diet. It is typically intended as such in discussions related to media ethics and media pluralism (Helberger, 2011; Hoffmann et al., 2015; Burri, 2019). Theoretically, it is sustained by a vast literature and all democratic models (Bozdag and Van den Hoven, 2015), in the liberal one particularly for the concept of ‘marketplace of ideas’ while in the deliberative one to promote open-mindedness and mental flexibility (Helberger, 2019). More generally, it sustains the fundamental right to autonomously seek and be exposed and eventually assess alternative fact, viewpoints, worldviews, with the chance to raise that emotional anxiety that may trigger belief change (Marcus, 2010) or simply to preserve a common base of facts to discuss.

Basically, political serendipity it might be achieved either through the attempt to balance the political news offer by design, either to proactively attempt to expose to challenging and alternative views in a highly personalized manner. On the one hand, however, being actively exposed to challenging information—eventually serendipitous—may not necessarily result in experience of diversity, de-polarization and/or more tolerance. In some cases, the opposite may be true. Polarized individuals radicalize further while exposed to challenging information (Quattrociocchi et al. 2016). Experiencing serendipity especially requires attitudes of open-mindedness and sagacity that are, above all, an educational issue. Yet, political serendipity by design could actually help to prevent people to begin to radicalize (Reviglio, 2017). On the other hand, there may be problems related to political hyper-personalization and sensational serendipity. In other words, manipulative political micro-targeting. Facebook actually sold user vulnerabilities, passions or fears, to political interest groups (Kohl et al. 2019). For example, during the Brexit referendum Vote Leave commissioned the Canadian company Aggregate AIQ to create 1433 more or less explicit pro-Brexit customised adverts to persuade voters through their apparent passions, desires or fears. Therefore, it may be better to provide users affordances. More concretely, Sunstein (2017b) proposed that social media could create a “serendipity button” for news and opinions, allowing people to opt in, especially during elections. Related stories at the bottom of a “post” also seem to help in counteracting misinformation or simply enriching a user perspective in a serendipitous way (Bode and Vraga, 2015). Another example to sustain political serendipity as an agonistic approach to political news may be Flipfeed, a MIT Lab-made Twitter plug-in that provides to the users the possibility to scroll the feed of a random individual which resides in a far ideological spectrum from one’s own.

Discussion

As outlined in the article, there are two main interpretations in the design of artificial serendipity, particularly in recommender systems, namely pseudo-personalized serendipity and hyper-personalized serendipity. Even if the latter is found on the serendipity spectrum, it is less likely to be as serendipitous as pseudo-personalized serendipity. In fact, the actual difference between the two is the expected accuracy of the recommendation. More “pure” – thus more unexpected – serendipity is more likely to occur through (semi or even non) personalized recommendations. In the case of hyper-personalized recommendations, to be truly serendipitous they should be not only useful or surprising but also meaningful, memorable, insightful, information which encapsulates quality and epistemic relevance (Floridi, 2006). These should also fairly attempt to stimulate individual progress and societies cohesion. Ideally, as users and citizens we need and want both hyper-personalization and pseudo-personalization. Hence, from a theoretical level it is needed to find a balance. Still, from a practical level it is hard to argue any optimal degree of pseudo- and hyper- personalization. Also, a right level of trade-off between the provider’s and users’ interests is debatable (Milano et al., 2019). Eventually, being able to identify personalization’s accuracy in particular items as well as in the general consumed media content may be the basis for autonomous choice, if a proper agency is afforded by design.

In order to increase serendipitous encounters, similarly to the dynamic relation between randomization, personalization and generalization suggested by Carr (2015), designers and engineers should strive to balance pseudo-personalization, hyper-personalization and non-serendipity, that is, all that information that ex-post did not unfold in any serendipitous experience (see Figure 2). The latest represents the assurance that news feeds are not all or excessively hyper-personalized, so that individual and political serendipity are cultivated so that a user actually expands his/her horizons and it is encountered information one may (not) like, thus leaving space for generalization and diversification. Yet, it is exactly this externality that sustains serendipity as an ethical principle in democratic societies, by diversifying information, preventing hyper-personalization and sustaining a stronger common base of facts and ideas, outside one’s filter bubble and echo chambers (that are, to some extent, natural phenomena). This framework resonates with a core function of traditional media, that is, to provide ‘reliable surprises’ in order to balance familiarity and chaos (Schönbach 2007) and, similarly, a balance between convergent and divergent systems (de Melo, 2018). Despite some inevitable generalizations, such a preliminary theoretical framework serves as a preliminary attempt to portray significant nuances of artificial serendipity and to inform designers on how to create more ethical design and algorithms.

Conclusions

Serendipity is a polymorphic and polysemantic phenomenon. As such, different yet related disciplines have interpreted and employed the concept in different ways. The article investigated the research history of serendipity in digital environments to seeks to map the conceptual space of ‘artificial serendipity’. This was done carrying out an interdisciplinary literature review and defining and discussing relevant terms in the area, in particular the distinction between hyper-personalized and pseudo-personalized serendipity. These have been made to further develop the study of serendipity in digital environments. In fact, artificial serendipity proved to be a technically volatile and a conceptually nuanced ethical principle. Though, it is also a beneficial design principle for both individuals and democratic societies. In fact it could help to burst filter bubbles and echo chambers, particularly in personalized news feeds. Cultivating serendipity is individually desirable and socially beneficial. Its design can sustain media pluralism and strengthen human rights, such as privacy, freedom of expression and the right to receive information.

As of now, many research gap remain in the study of serendipity in digital environments. Discussions and, eventually, consensus on the definitions, the design and the assessment of serendipity need to be further reasoned. Also, the practical effectiveness in bursting filter bubbles and soften echo chambers is questionable. Digital literacy, critical thinking and high quality media remain fundamental preconditions for a beneficial expression of serendipity in digital environments. There is certainly room for research on serendipity in learning environments, conceived as a soft-skill to master. Nonetheless, under the current business model of mainstream social media, for example, serendipity may be limited, and often mingled with sensational serendipity. In fact, when designed for profit-making alone, or when they are mainly profit-driven, “algorithms necessarily diverge from the public interest” (Benkler, 2019). In order to increase serendipity, designers and engineers should recognize the nuances of designing for serendipity – especially the trade-off with accuracy – and, from an ethical standpoint, attempt to balance hyper-personalized and pseudo-personalized recommendations, even throughout design affordances and information discovery tools. Our current conceptual toolbox is in fact no longer fitted to address new ICT-related challenges and “the lack of a clear conceptual grasp of our present time may easily lead to negative projections about the future: we fear and reject what we fail to semanticise” (Floridi, 2015). These concepts can eventually better inform and inspire educators, designers and engineers to help individuals find the information they need, not just the information they think they need, or that algorithms presume, and sometimes even deceive, they need.

Acknowledgements

The author wish to acknowledge and thank the professor Stephen Makri for his constructive comments that helped sharpen arguments and clarify the conceptual distinctions.

About the author

Urbano Reviglio is a PhD Candidate in International Joint Doctorate in Law, Science and Technology Erasmus+ (LAST-JD), University of Bologna. He studies Information Ethics, Internet & Society, and Media Studies. He can be contacted at urbanoreviglio@hotmail.com.

References

- Austin, J. H. (2003). Chase, chance, and creativity: The lucky art of novelty. Mit Press.

- Balabanović, M., & Shoham, Y. (1997). Fab: content-based, collaborative recommendation. Communications of the ACM, 40(3), 66-72.

- Benkler, Y. (2019). Don’t let industry write the rules for AI. (2019, May 05). Nature. Retrieved from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01413-1

- Bernier, C. L. (1960). Correlative indexes VI: Serendipity, suggestiveness, and display. Journal of Documentation, 11(4), 277-287.

- Björneborn, L. (2017). Three key affordances for serendipity: Toward a framework connecting environmental and personal factors in serendipitous encounters. Journal of Documentation, 73(5), 1053–1081.

- Bogers, T., & Björneborn, L. (2013). Micro-serendipity: Meaningful coincidences in everyday life shared on Twitter. iConference, 2013, 196–208.

- Bol, N., Dienlin, T., Kruikemeier, S., Sax, M., Boerman, S. C., Strycharz, J., ... & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). Understanding the effects of personalization as a privacy calculus: analyzing self-disclosure across health, news, and commerce contexts. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(6), 370-388.

- Bozdag, E., & Timmermans, E. (2011). Values in the filter bubble Ethics of Personalization Algorithms in Cloud Computing. In Proceedings, 1st International Workshop on Values in Design– Building Bridges between RE, HCI and Ethics, Lisbon.

- Bozdag, E., & van den Hoven, J. (2015). Breaking the filter bubble: Democracy and design. Ethics and Information Technology, 17(4), 249–265.

- Buchem, I. (2011). Serendipitous learning: Recognizing and fostering the potential of microblogging. Form@ re-Open Journal per la formazione in rete, 11 (74), 7-16.

- Burri M. (2019) Discoverability of Local, National and Regional Content Online: Mapping Access barriers and Contemplating New Orientation Tools, discussion paper.

- Campanario, J. M. (1996). Using citation classics to study the incidence of serendipity in scientific discovery. Scieontometrics, 37 (1), 3–24.

- Campos, J., & Figueiredo, A. D. (2002). Programming for serendipity. In Proceedings of the AAAI fall symposium on chance discovery— The discovery and management of chance events.

- Carr, P. L. (2015). Serendipity in the stacks: Libraries, information architecture, and the problems of accidental discovery. College & Research Libraries, 76, 831–842.

- Carr, N. (2016). Utopia is creepy: And other provocations. New York: W W Norton & Co Inc.

- Darbellay, F., Moody, Z., Sedooka, A., & Steffen, G. (2014). Interdisciplinary research boosted by serendipity. Creativity Research Journal, 26 (1), 1-10.

- de Melo, R. M. C. (2018). On serendipity in the digital medium: Towards a framework for valuable unpredictability in interaction Design.

- De Rond, M. (2014). The structure of serendipity. Culture and Organization, 20(5), 342–358.

- Erdelez, S. (1997). Information encountering: a conceptual framework for accidental information discovery. In Proceedings of an international conference on Information seeking in context (pp. 412–421). Taylor Graham Publishing, London.

- Erdelez, S. (2004). Investigation of information encountering in the controlled research environment. Information Processing & Management, 40(6), 1013–1025.

- Erdelez, S., & Jahnke, I. (2018). Personalized systems and illusion of serendipity: A sociotechnical lens. In Workshop of WEPIR 2018.

- Floridi, L. (2002).What is philosophy of information. Metaphilosophy, 33(1-2), 123-145.

- Floridi, L. (2008). Understanding epistemic relevance. Erkenntnis, 69(1), 69-92.

- Floridi, L. (2011). The informational nature of personal identity. Minds and Machines, 21(4), 549.

- Floridi, L. (2015). The onlife manifesto. Cham: Springer.

- Floridi, L. (2016). Tolerant paternalism: Pro-ethical design as a resolution of the dilemma of toleration. Science and Engineering Ethics, 22(6), 1669–1688.

- Fogg, B. J., Lee, E., & Marshall, J. (2002). Interactive technology and persuasion. The Handbook of Persuasion: Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Merton, R. K., & Barber, E. (2006). The travels and adventures of serendipity: A study in sociological semantics and the sociology of science. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Edward Foster, A., & Ellis, D. (2014). Serendipity and its study. Journal of Documentation, 70(6), 1015-1038.

- Heinstrom, J. (2010). From fear to flow: personality and information interaction. Elsevier.

- Gibson, J. J. (2014). The ecological approach to visual perception: Classic edition. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Gup, T. (1997). Technology and the end of serendipity. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 44 (21), A52.

- Harambam, J., Helberger, N., & van Hoboken, J. (2018). Democratizing algorithmic news recommenders: How to materialize voice in a technologically saturated media ecosystem. Philosophical Transactions A, 376(2133), 20180088.

- Helberger, N. (2011). Diversity by design. Journal of Information Policy, 1, 441–469.

- Helberger, N., Karppinen, K., & D’Acunto, L. (2016). Exposure diversity as a design principle for recommender systems. Information, Communication & Society, 21, 1–17.

- Helberger, N. (2019). On the democratic role of news recommenders. Digital Journalism, 1-20.

- Hendler, J., & Hugill, A. (2013). The syzygy surfer:(Ab) using the semantic web to inspire creativity. International Journal of Creative Computing, 1 (1), 20–34.

- Hildebrandt, M. (2009). Profiling and AmI. In The future of identity in the information society (pp. 273–310). Berlin: Springer.

- Hildebrandt, M. (2017). Privacy as protection of the incomputable self: Agonistic machine learning. Available at SSRN 3081776.

- Hildebrandt, M., & Koops, B. J. (2010). The challenges of ambient law and legal protection in the profiling era. The Modern Law Review, 73(3), 428–460.

- Hoffmann, C. P., Lutz, C., Meckel, M., & Ranzini, G. (2015). Diversity by choice: Applying a social cognitive perspective to the role of public service media in the digital age. International Journal of Communication, 9(1), 1360–1381.

- Kohl, U., Davey, J., & Eisler, J. (2019). Data-driven personalisation and the law-a primer: collective interests engaged by personalisation in markets, politics and law. (Forthcoming).

- Kop, R. (2012). The unexpected connection: Serendipity and human mediation in networked learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(2), 2–11.

- Kotkov, D., Wang, S., & Veijalainen, J. (2016). A survey of serendipity in recommender systems. Knowledge-Based Systems, 111, 180–192.

- Krotoski, A. (2011). Digital serendipity: be careful what you don’t wish for. The Guardian International Edition.

- Lynch, M. P. (2016). The Internet of us: Knowing more and understanding less in the age of big data. New York: WW Norton & Company.

- Makri, S. (2014). Serendipity is not Bullshit. Paper presented at the EuroHCIR 2014, The 4th European Symposium on Human- Computer Interaction and Information Retrieval, 13 Sep 2014, London, UK.

- Makri, S., & Blandford, A. (2012). Coming across information serendipitously— Part 1, p. A process model. Journal of Documentation, 68(5), 684–705.

- Makri, S., Blandford, A., Woods, M., Sharples, S., & Maxwell, D. (2014). “Making my own luck”: Serendipity strategies and how to support them in digital information environments. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 65(11), 2179-2194.

- Maloney, A., & Conrad, L. Y. (2016). Expecting the unexpected: Serendipity, discovery, and the scholarly research process (white paper), Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Marcus, G. E. (2010). Sentimental citizen: Emotion in democratic politics. University Park: Penn State Press.

- Meckel, M. (2011). “Sos—save our serendipity” , Personal Blog. Retrieved from: https://www.miriammeck el.de/2011/10/11/sos-save-our-serendipity/.

- McCay-Peet, L., & Toms, E. G. (2017). Researching serendipity in digital information environments. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services, 9(6), i–i91.

- Milano, S. & Taddeo, M. & Floridi, L. (2019) Recommender Systems and their Ethical Challenges. (Forthcoming).

- O’Connor, B. (1988). Fostering creativity: Enhancing the browsing environment. International Journal of Information Management, 8(3), 203–210.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think. New York: Penguin.

- Race, T., & Makri, S. (2016). Accidental information discovery: Cultivating serendipity in the digital age. Cambridge: Chandos Publishing.

- Reviglio, U. (2017). Serendipity by design? How to turn from diversity exposure to diversity experience to face filter bubbles in social media. In International Conference on Internet Science (pp. 281–300). Springer, Cham.

- Reviglio, U. (2019). Serendipity as an emerging design principle of the infosphere: challenges and opportunities. Ethics and Information Technology, 21(2), 151-166.

- Rice, J. (1988). Serendipity and holism: The beauty of OPACs. Library Journal, 113(3), 138-41.

- Rubin, V. L., Burkell, J., & Quan-Haase, A. (2011). Facets of serendipity in everyday chance encounters: A grounded theory approach to blog analysis. Information Research, 16(3), 27.

- Saini, A. K., & Khurana, V. K. (2013). Using Serendipity for ICT Development. Global Journal of Enterprise Information System, 5(2).

- Schmidt, E. (2006). How we’re doing and where we’re going. Google Inc. Press Day 2006.

- Schönbach, K. (2007). ‘The own in the foreign’: Reliable surprisean important function of the media? Media, Culture & Society, 29(2), 344–353. (Makri 2014).

- Sen, A. (2005). Human rights and capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 6(2), 151–166.

- Shannon, C. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423.

- Stiegler, B. (2017). The new conflict of the faculties and functions: Quasi-causality and serendipity in the anthropocene. Qui Parle, 26(1), 79–99.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2017b). In praise of serendipity. The Economist.

- Tewksbury, D., Weaver, A. J., & Maddex, B. D. (2001). Accidentally informed: Incidental news exposure on the World Wide Web. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78 (3), 533-554.

- Thurman, N. (2011). Making ‘The Daily Me’: Technology, economics and habit in the mainstream assimilation of personalized news. Journalism, 12 (4), 395–415.

- Thurman, N., & Schifferes, S. (2012). The future of personalization at news websites: Lessons from a longitudinal study. Journalism Studies, 13 (5–6), 775–790.

- Tomic, T. (2010). The Philosophy of Information as an Underlying and Unifying Theory of Information Science. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 15 (4), n4.

- Turing, A. M. (1950). ‘Computing machinery and intelligence’. Mind, 59, 433–460.

- van Andel, P. (1994). Anatomy of the unsought finding. serendipity: Origin, history, domains, traditions, appearances, patterns and programmability. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 45 (2), 631–648.

- Yadamsuren, B., & Erdelez, S. (2016). Incidental exposure to online news. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services, 8 (5), i–i73.

- Zuckerman, E. (2008). Serendipity, echo chambers, and the front page. Nieman Reports, 62 (4), 16.

- Zuckerman, E. (2013). Rewire: Digital cosmopolitans in the age of connection. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.