Qualification requirements in Norwegian public libraries – an analysis of job advertisements

Beate Bjørklund, and Ragnar Audunson.

Introduction. For some years practitioners have observed a tendency that local government authorities advertising vacant professional positions in public libraries do not specify an educational background from library and information science as a mandatory qualification for applicants. Are the observers correct? This study aims at answering this question by analysing advertisements for vacant positions.

Method. All advertised vacant positions registered at the Norwegian Labour and Welfare organisation in the years 2005, 2010 and 2015 satisfying a definition of having a professional responsibility were coded and analysed in order to see if the demand for professional education has changed over time.

Analysis. A consecutive cross-sectional study was undertaken using quantitative content analysis.

Results. The research confirmed that a development has taken place with a reduced weight on library education and an increased weight on personal and interpersonal traits between 2005 and 2015. There are differences between local government authorities according to size. The tendency not to ask for library education is strongest with the very small authorities and a few very large cities.

Conclusions. Further research with longer time series as well as comparative research is needed to get a fuller understanding of the development.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper889

Background and overriding research question

Over the last few years, the hiring policies of the public libraries of Norway have been discussed from several angles (Lindstad, 2009; Svartberg Arntzen and Svaleng, 2009; Rognerød et al., 2014) in several fora. The discussion has been partly grounded in legal changes and partly in trends within the field of practice, particularly among leading managers in the public library field.

In 2013, the Norwegian parliament revised the Norwegian law on public libraries (Folkebibliotekloven, 1985). In part the mission statement was amended; in addition to the traditional role of promoting cultural activities and learning by providing access to books and other kinds of media, libraries were given the task of being independent meeting places and arenas for public debate in their communities. In addition, the legal reform reduced the requirements regarding library and information science education for local government library directors. Since 1985, the Norwegian law on public libraries has required all local governments to have a local public library and that the director shall be an educated librarian. For all practical purposes, being an educated librarian has been defined as having completed a 3-year bachelor program in library and information science or its equivalent. The legal reform of 2013 changed this definition. The required qualification according to the revised law is a bachelor’s degree containing minimum 60 ECTS, i.e. one-year library and information science.

The Norwegian development with respect to reducing educational requirements in library and information science is far from unique. All the Nordic countries have library laws. The Danish library law on public libraries took away the educational requirements in library and information science as early as 2002. Finland got a new law on public libraries in 2016, also omitting the former requirements regarding library and information science-education. The new law only states that municipal library directors are required to have a relevant higher academic degree. The Swedish library law has never contained educational requirements.

Then comes trends in the field of practice, particularly among some dominant and very articulate library directors. The library directors of the six largest cities in Norway, in a letter to then Minister of Culture Thorhild Widway, expressed that they believed the current library education was not suitable for the future needs of the public libraries and that they at the time recruited other skills than that of the traditional librarian (Danielsen et al., 2014). Shortly after, the job advertisement for the new teen library in Oslo was published, asking for DIY-inventors, cooks and artists (Oslo kommune - kulturetaten, 2015), making no mention of the title of librarian. In addition, the advertisement did not specifically ask for library and information science education, electing to request relevant higher education instead (Oslo kommune - kulturetaten, 2015).

After 1985, and especially in the new millennium the relevance of libraries and librarians have been increasingly questioned (Audunson, 2015). It is illustrating for this professional trend that in 2009 two young librarians published an article in the main Norwegian journal for librarianship, Bok og bibliotek, stating that one of the main problems for libraries is that there are too many librarians working there (Svartberg Arntzen and Svaleng, 2009). One will probably not find very many representatives of other profession defining it as a problem that there are too many of them in the profession’s core institution, for example too many teachers in the schools. These developments led us to study the question of if and how these trends are reflected in published job advertisements. The overriding research question is:

Do these developments reflect that the profession of librarianship is about to lose its jurisdiction over the public library field?

More specifically, we have chosen the following research questions based on interest, background and previous research:

Which qualifications do the Norwegian public libraries desire in new staff members and does it change over time?

- Is, when analysing advertisements over time, the hypothesis that the demand for candidates with a degree in library and information science is reduced, confirmed?

- Which traits are sought beyond education? What is the balance between traits referring to professional competencies and interests compared to generic personal and interpersonal traits?

- Are there differences between local governments according to size?

Literature Review

Changes in library employment policies have been analysed through content analysis of job advertisements since the 1950’s (Beile and Adams, 2000) and is, according to White (1999), a relatively common study method in the field. White conducted a literature review of such studies and found that they can be divided into three main groups: those who require specific types of positions, those who want specific traits and those who have a broader scope. The literature review done by Henricks and Henricks-Lepp (2014) support White's (1999) results. Further, most of these studies have been conducted in academic libraries or in relation to academic library positions (Adkins, 2004; Henricks and Henricks-Lepp, 2014; White, 1999). Our search results align with these tendencies, and we found very few content analyses of job advertisements in public libraries, none of them from Scandinavia.

Denice Adkins (2004) conducted a longitudinal qualitative content analysis of the changes in public library youth services in the United States between 1971 and 2001. She found an increase in the number of public librarians, with 87% of employers desiring library and information science education. However, she also found a decrease in the requests for experience, combined with the number of specific competencies and personal traits mentioned almost tripled. She also noted that the word count of the job advertisement increased over time.

Kennan et al. (2006) conducted a longitudinal explorative study of the library field in Sydney, Australia based on data from 1974 to 2004. The study explored changes in what demands were placed on the information profession by employers, as seen in job advertisements. They found a significant decrease in positions requesting an educational background in library science, but an increase in the need for previous experience. Like Adkins (2004) they found an increase in the word count of the job advertisements, as well as the number of traits requested being tripled.

Gerolimos and Konsta (2008) conducted a study of job advertisements from Great Britain, Canada, Australia and USA from the years 2006 and 2007. With a background in the shift to a more digital society, the study explored desired qualifications and traits of the library profession as expressed in job advertisements. They found a focus on communication, as well as an expected desire for education and experience within the library field.

Henricks and Henricks-Lepp (2014) conducted a longitudinal, quantitative content analysis in the United States for the period 2000-2011. They focused on the characteristics of management and leadership that was desired in library directors of public libraries. Their results pointed toward employers desiring management over leadership.

Both Adkins (2004) and Kennan et al. (2006) found that the word count increased between 1971 and 2004, findings that are supported by Wise et al. (2011). When it comes to requests for previous experience, Adkins (2004) and Kennan et al. (2006) have contradicting results, but this may be a result of different selection criteria as well as the studies being conducted in different countries. These studies and their literature review (Adkins, 2004; Gerolimos and Konsta, 2008; Henricks and Henricks-Lepp, 2014; Kennan et al., 2006) clearly points toward a library field with an increased need for computer skills and personal and intrapersonal traits.

This study expands the available research by focusing on the public libraries as they are underrepresented compared with the academic libraries when it comes to needed qualifications as expressed in job advertisements. In addition, it provides a window for comparison of trends on a global scale.

Theoretical background

Our research into the possible changes in the strength of the relation between the public libraries and the librarians is informed by two theoretical approaches: Theory of the professions and institutional theory.

When it comes to theory of the professions, one concept is particularly important: the concept of jurisdiction (Abbott, 1988). Professions are usually defined as a group of practitioners whose practice is grounded in a college or university-based education and claiming to rely upon a scientifically based knowledge base. Members of the profession make up a network binding them together across their belonging to concrete workplaces. Important elements constituting the professional network are professional journals, professional associations, professional conferences and the professional education, creating a professional alumnus with the same knowledge base, sharing perceptions of the profession’s social missions, sharing a professional ethic, etc.

Based on these elements, professions tend to claim jurisdiction over a given field of practice, i.e., a monopoly regarding certain practices and responsibilities. Graduates from teacher training colleges claim jurisdiction over certain responsibilities in schools. Graduates from law schools claim jurisdiction over conducting cases before the court of law, graduates from nursing schools claim jurisdiction over certain responsibilities in hospitals etc. Jurisdiction can be founded in a general acceptance in the environment that the interests of society as well as the interests of the clients are best served with giving the profession in question a de facto monopoly over the field of practice. Whether or not a profession’s claim of jurisdiction is accepted by the environment, depends on the strength of the profession’s institutionalisation. (March and Olsen, 1989).

For some fields of practice, it is generally taken for granted that only members of a given profession can be entrusted with the responsibility of being practitioners in the field. It is illegal to practice as a medical doctor without an authorisation from the health authorities, even if you have passed all exams at a medical faculty. Most people would probably, no matter the legal foundation of the medical doctor’s jurisdiction over the field of medicine, go to a qualified doctor of medicine to have their illnesses treated. The profession’s jurisdiction has a broad and popular legitimacy. The institutional basis of the profession’s jurisdiction is extremely strong, legally rooted as well as rooted in a broad and general legitimacy. It is not illegal for a person without a degree from a teacher training college to practice as a teacher. Parents, political authorities as well as the general public would, however, probably regard it as highly problematic if a large proportion of the teachers in public schools lack pedagogical education. The profession of teachers enjoys a broad popular legitimacy, although their jurisdiction is not as strong as that of doctor of medicine. Journalism is also a profession and many universities offer degrees in the field. Few, however, would probably be concerned if a newspaper or a broadcasting company employs a person without a degree in journalism as a journalist. A proposal to protect the journalists’ jurisdiction over their field by law would probably be supported by very few if any. The profession’s institutionalisation is weak.

Where do we find public librarianship on this scale from very strong institutionalisation of professional jurisdiction (doctor of medicine) through medium-strong institutionalisation (teachers) to a weak institutionalisation (journalists)? In 1971, the Norwegian parliament for the first time adopted a law on public libraries stating that local government library directors were supposed to have a degree in library and information science. Then it was restricted to local government authorities with 8000 inhabitants or more. In a legal revision in 1985, the educational requirements were strengthened to comprise all local government authorities, no matter the number of inhabitants. Now the development seems to go in the opposite direction, weakening the legally grounded educational requirements as well as perceptions in the field regarding the value of an educational background in library and information science and thus seemingly weakening the jurisdiction of librarians over the public libraries.

Method

We have established there is little previous research in Norway to build on, and as the research question is whether the requirements of the Norwegian public library hiring committees have changed over time, we have elected to conduct a consecutive cross-sectional study. As it is possible to analyse trends in order to answer the research questions by using secondary data (Ringdal, 2013), we have opted to utilise archived job advertisements. Trend analysis’ demands that the subject matter is analysed identically (Ringdal, 2013, p. 148), which is easily satisfied by conducting a document analysis where each unit is treated equally.

It is necessary to employ a quantitative method in order to conduct a trend analysis on a societal level, as quantitative methods utilise a larger representative selection and numerical data (Ringdal, 2013). Seeing as the empirical data consists of text data, which is considered qualitative data, we have elected to conduct a quantitative content analysis.

Converting text to numerical data in a quantitative content analysis requires techniques and data registration seeking a systematic, objective and quantitative description of the content in a message (Østbye et al., 2013, p. 210)). In order to ensure this, it is important to create a code book. Relying on a code book during the content analysis ensures that it will be possible to replicate the results. Following the conversion of the data from text to numbers, it is possible to analyse the data statistically, allowing us to draw conclusions regarding the surrounding connections from text (Bratberg, 2014).

Definition

A librarian position could be defined as a position in libraries which requires an education background in library science. Our research question, however, questions the extent to which employers require librarians to have a degree in library and information science. A definition based on education, therefore, is not workable.

Lankes (2016) defines librarians by their social mission independent of where they are working: 'the mission of librarians is to improve society through facilitating knowledge creation in their communities' (Lankes, 2016, p. 17)

We are occupied with employment criteria in public libraries. A definition disregarding institutional affiliation is, therefore, not workable for our purposes.

The research project Archives, Libraries and Museums as Public Sphere Institutions (ALMPUB), in connection with a survey with librarians in public libraries as target group, used the following definition to identify respondents:

A librarian is an employee with an educational background in library and information science or an employee with any educational background who has the development and/or mediation of library services to the public as a central part of his/her responsibilities (Audunson et al., forthcoming).

We have, in line with this definition, chosen to include and analyse advertisements asking for staff members with a professional responsibility for developing and/or mediating library services to the public.

A non-librarian position was formerly library positions that did not request a library and information science background. In this study, these positions are defined as office positions and circulation staff; that is positions without an overarching responsibility beyond the daily tasks.

Selection

Job advertisements are comparable over time as they follow a certain structure and thus have a partially standardised form (Bratberg, 2014), thus they function well as data basis. The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) registers, publishes and archives the overwhelming majority of all vacant positions in Norway and we have selected advertisements from this database.

In order to conduct a longitudinal study, we have included data from more than one year. Based on the available data (2003-2017) we decided to choose years in a five-year interval, and have limited the selection to 2005, 2010 and 2015.

We have further limited the data to permanent librarianship positions. This is partly due to time constraints, but it is also due to other library positions being of little interest to applicants from a library science background. We have not limited the selection based on work hours as there are several positions in public libraries that are not full-time (Nasjonalbiblioteket, no date), and we feared excluding these would affect data from parts of the country negatively.

When extracting data from NAV’s database, we have utilised a code for classifying occupations developed by Norway’s Central Bureau of Statistics (STYRK98), which contains a code for library. The selection included titles such as library assistant to ensure all relevant data was included. During coding, it became apparent that the use of these codes was inconsistent, and we found librarianship positions tagged with non-librarianship codes and vice versa.

The extraction was based on the STYRK98 codes and the selected years alone, and the other criteria were added as the 830 units were coded in order to ensure a wide selection. The resulting extract included employer, title of the vacant position, workplace and the full text. Unfortunately, the data on work hours and whether the position was permanent was not included in the initial extraction and this data was subsequently requested and added at the end of the coding process for the included dataset.

In conclusion, the study is thus based on analysis units in the form of job advertisements for public libraries in Norway, published on the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration website (http://www.nav.no) during 2005, 2010 and 2015 wanting to hire for permanent librarianship positions.

Codebook

After multiple revisions, our final codebook included 75 variables used in the coding of the units. The independent variables mainly consist of the year of publication, county, hours per week and municipality population. The population variable has been categorised into four values. Three of these are based on an aggregated standard from the statistical bureau, sorting them into small 0-4 999), medium (5 000-19 999) and large (20 000+) municipalities (Langørgen, Løkken, and Aaberge, 2015, p. 10). The fourth category, named big city libraries, consists of the six largest cities in the country; Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, Stavanger, Kristiansand and Bærum municipality (Danielsen et al., 2014).

The dependent variables have a large range in order to answer the research questions regarding qualifications, be they skills, education or personal traits. Regarding library education two variables are used to distinguish between library science being mentioned as a possible background, and it being a requirement for being hired in the position.

We have elected to group traits that are synonyms together in order to limit the number of variables. An example of this is grouping ‘active environment’, ‘juggling many tasks’, ‘high activity level’ and ‘demands rapid adaptation’ together into the variable ‘multi-tasker’ as they all point to an active work place where there may be high demands on the librarian from the public.

Coding

The data received consisted of 830 job advertisements. When duplicates and advertisements not meeting the criteria were excluded, we were left with a dataset of 235 units. The data was coded to the statistical analysis program SPSS. We elected to do this manually rather than automatically in order to capture the data as completely as possible and accounted for intersubjectivity by having only one coder. Where some advertisements did not have any data, we contacted the employer and requested a copy from them in order to get as wide a selection as possible. Where multiple positions were advertised together, we have coded them as separate entities, unless they were part-time positions where the texts specified that they could be combined upon request. After coding, the data was analysed statistically through univariate and bivariate analysis. In order to calculate the relevance of the statistic in a longitudinal perspective, we have employed chi square tests (χ²). A result is significant when p < 0.01.

Findings

Overview

The number of job advertisements have increased during the time period, from 34 in 2005 to 124 in 2015, an increase of 265 percent. In 2010 we found 77, yielding an approximately linear increase over time. Thus, the change was gradual, indicating that the change is not due to mistakes during archiving.

At the same time there was a reduction in the number of employees in Norwegian public libraries (Nasjonalbiblioteket, no date). Furthermore, the Norwegian Union of Librarians confirmed via the telephone that their number of retirees had more than doubled during the period, while data from the NAV State Register of Employers and Employees (Aa-registeret) reflects an increase in young employees and a decrease in older employees. Based on these data we hypothesise that the increase in job advertisements over time is caused by a generational change in Norwegian public libraries. It is possible that increased job mobility is also contributing to the increase in job advertisements, but the majority would still be accounted for by the massive increase in retirees during the time period.

The data is relatively evenly distributed between the counties. Oslo, the capital of Norway is on top with 15 percent of the total number of job advertisements. We found an approximately even distribution between municipality size as well (from 18 % to 33 %).

| Size of municipality | Frequency | Percent (%) | Cum. percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small municipalities | 43 | 18 | 18 |

| Medium municipalities | 77 | 33 | 51 |

| Large municipalities | 63 | 27 | 78 |

| Big city libraries | 52 | 22 | 100 |

| Total | 235 | 100 |

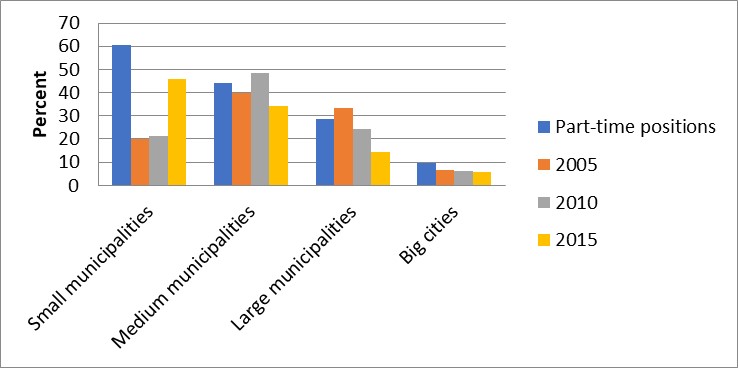

Most of the collected job advertisements were for full-time positions (64%), while 35% were part-time. While the number of hours varied between 20 and 80% of a full-time position, the majority was 50%. Not unexpectedly, there is a significant correlation between part-time positions and the size of the municipality, with 61 percent of the part-time positions offered in small municipalities, (χ² (6) = 34.327, p < 0.001). At the same time 61 percent of the jobs offered in small municipalities have management or leadership responsibilities. As indicated in Figure 1, the use of part-time positions in larger municipalities have declined over time. This may be caused by the employers replacing part-time positions with full-time positions over time, as the hours in Norwegian public libraries have been consistent while the number of employees have declined (Nasjonalbiblioteket, no date).

Education

There is no requirement by law for a library science background for positions in public libraries, except for the position of library director (Folkebibliotekloven, 1985). It has been common to require or request for most positions regardless. Of 235 job advertisements, only 4% did not request higher education in general, and of these 4%, 78% were part-time positions.

57% of the job advertisements required a library science background. This requirement has decreased significantly over time from 2005 (79%) to 2015 (49%), (χ² (2) = 10.29, p = 0.006).

The library science education was mentioned in 84% of the collected job advertisements, with a decline from 2005 (94%) to 2010 and 2015 (82%). Of the 16% where library science was not mentioned specifically, 61% of these requested relevant education. These employers are presumably accepting library science as relevant, but this is not clear. Other education backgrounds were mentioned in 23% of the job ads where library science was specified. When all job ads mentioning another background than library science are viewed together, whether it is mentioned in combination with library science or not, other relevant education was mentioned in approximately four out of five advertisements. Other education backgrounds requested specifically were culture, leadership, management, computer science, literature, education, film, and music.

When doing a cross-table comparison between municipality size and whether library education was required, we found an increase in requirement with the size of the municipality, from 54% in small municipalities to 75% in large ones, (χ² (3) = 23.677, p < 0.001). We found no significant change in this distribution over time.

| Library and information science education required | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | |||

| Municipality size | Small municipalities | Count | 20 | 23 | 43 |

| % within municipality size | 46% | 54% | 100% | ||

| Medium municipalities | Count | 29 | 48 | 77 | |

| % within municipality size | 38% | 62% | 100% | ||

| Large municipalities | Count | 16 | 47 | 63 | |

| % within municipality size | 25% | 75% | 100% | ||

| Big city libraries | Count | 36 | 16 | 52 | |

| % within municipality size | 69% | 31% | 100% | ||

| Total | Count | 101 | 134 | 235 | |

| % within municipality size | 43% | 57% | 100% | ||

The big cities are an exception (31%). In a longitudinal view of the big cities’ preference, shown in Table 3, we found a reduction from 2005 (80%) to 2015 (0%), (χ² (2) = 29.47, p < 0.001). While the big cities mention library education as an education alternative more often than they set it as a requirement in the job advertisement, there is a reduction over time for this as well, from 2005 and 2010 (80%) to 2015 (66%).

| Big city libraries | Year of publication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | Total | |||

| Library and information science required | No | Count | 1 | 6 | 29 | 36 |

| % within year of publication | 20% | 33% | 100% | 69% | ||

| Yes | Count | 4 | 12 | 0 | 16 | |

| % within year of publication | 80% | 67% | 100% | 31% | ||

| Total | Count | 5 | 18 | 29 | 52 | |

| % within year of publication | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | ||

Personal and interpersonal traits

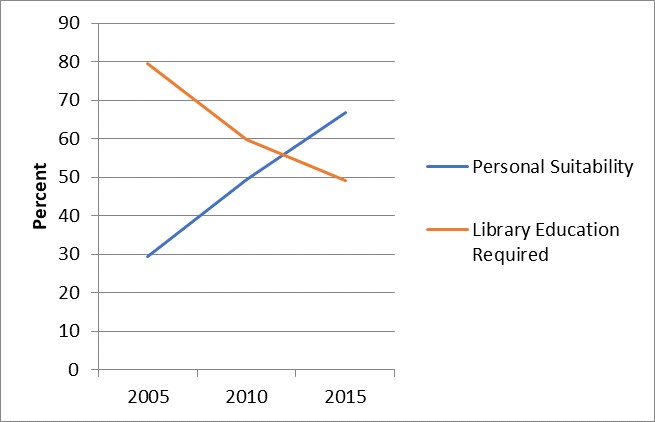

Specified traits were requested in 95% of the job ads. Not unexpected, the most popular are all general traits; collaboration (73%), personal suitability (56%), service-minded (51%) and independent (50%). The overall requests for traits increased by 113% from 2005 to 2015. This indicates a shift toward valuing traits more, which is supported by personal suitability emphasised increasing by 128% from 2005 (29%) to 2015 (67%), (χ² (2) = 17.13, p < 0.001).

While most general traits have been constant throughout the period, other traits such as flexible and visionary and development focused have increased over time, the latter from 9% in 2005 to 55% in 2015 (χ² (2) = 31.66, p < 0.001). This may be related to the change in the public library mission of 2013 charging libraries with being independent meeting places and arenas for public debate in their communities, something that is supported by an increase in requests for enthusiasm, communication, relation builder and public speaker.

| Personal and interpersonal traits | Overall | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration | 73% | 59% | 71% | 77% |

| Personal suitability | 56% | 29% | 49% | 67% |

| Service-minded | 51% | 44% | 52% | 52% |

| Independent | 50% | 47% | 49% | 52% |

| Development focused | 39% | 9% | 26% | 55% |

| Extroverted | 37% | 12% | 46% | 40% |

| Enthusiasm | 32% | 12% | 18% | 45% |

| Creative | 29% | 24% | 29% | 31% |

| Follows through | 29% | 24% | 21% | 36% |

| Flexible | 28% | 6% | 27% | 34% |

| Communication | 26% | 12% | 16% | 36% |

| Work well with children | 22% | 21% | 26% | 20% |

| Solution focused | 16% | 3% | 1% | 29% |

| Interested in library development | 16% | 3% | 13% | 21% |

| Structured | 15% | 3% | 13% | 19% |

| Result focused | 15% | 20% | 13% | 15% |

| Literature interested | 13% | 3% | 14% | 15% |

| Multi-tasker | 10% | 0% | 12% | 11% |

| Relation builder/td> | 9% | 0% | 4% | 15% |

| Leader | 8% | 0% | 9% | 10% |

| Dutiful | 6% | 0% | 3% | 11% |

| Community interested | 6% | 3% | 3% | 8% |

| Public speaker | 5% | 0% | 1% | 8% |

| Well-rounded | 2% | 0% | 4% | 2% |

| Total | 591% | 332% | 520% | 707% |

| n = | 235 | 34 | 77 | 124 |

When we compare the big cities with the other municipalities, we find that the big cities request traits 46% more often on average than the any of the other municipalities (which differ by 7%). We also find that the big cities are requesting the traits we have related to the change in library mission significantly more often than any of the other municipalities. The big cities also request creativity and being able to handle an active environment more often.

Experience

Experience was mentioned in 60% of the job advertisements, while competence was mentioned in 23%, when we exclude literature competence (31%). Literature competence was initially excluded as the requests often used other words such as education and experience.

The request for previous library experience is stable at approximately 34% of the job advertisements throughout the period. The other types of experience requested most often was relevant (9%) and children and teens (7%).

Computer knowledge in one variation or other was mentioned in 63% of the job advertisements: 20% as competence and 39% as general computer knowledge or experience. It is highly probable that either of the terms were used to ensure the employees were computer literate enough to successfully do the work assigned.

As previously stated, 34% of job advertisements requested library experience, of which 25% request experience from public libraries. Only 11% asked for library competence. Within library-related knowledge, reference work (0%) and knowledge management (4%) were not often requested, probably as they were considered a natural part of library science education or librarian experience. Knowledge management in the form of cataloguing knowledge were decreasing over time (from 15% in 2005 to 3% in 2010/2015), which may be due to the libraries increasingly centralising these services (χ² (2) = 11.089, p =0.004). 11% requested job seekers to have previous experience with their integrated library system, a request that increased with municipality size: from 9% in small municipalities to 19% in large ones, excluding big cities (0%).

Literature knowledge was requested in 31% of the job ads, with an increase in 2015 when it rose by 15% to a total of 38% (χ² (2) = 6.61, p =0.037). The big cities requested literature knowledge in 50% of their job ads, a ratio that on average is twice as often as the other municipalities, (χ² (3) = 12.31, p =0.006).

Enthusiasm for, and skill in mediation of literature and library services was requested in 46% of the job advertisements, which is more often than the 35% where it was specified as a work task. The number of requests also increased significantly over time from 24% in 2005 to 53% in 2015, (χ² (2) = 9.82, p =0.007). The requests increased linearly by size, and the difference between the big cities and the small municipalities was 23%.

There is a strong correlation between literature knowledge and literature mediation, (χ² (2) = 9.54, p =0.008).

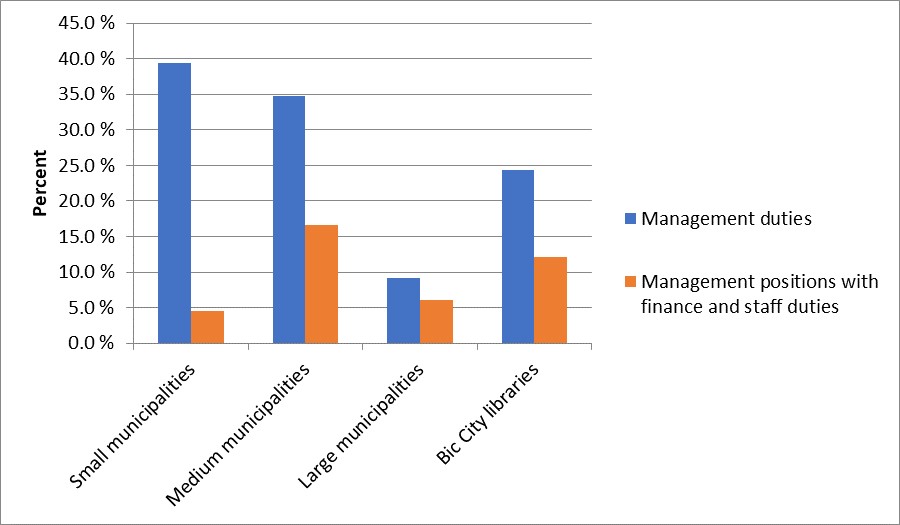

Management

28% of the job advertisements had management or leadership duties, of which 39% also had duties related to managing finances or staff. Some of the explanation for the discrepancy between these numbers may be related to 39% of the management positions being in small municipalities, while only 5% of the positions with finance and staff duties were there. As small municipalities often only have one position in their libraries, it is reasonable that this is the causation.

Summary

In summary, we found that there has been a reduction in the requests for library education, especially as concerns the number of positions requiring library education in order to hire. At the same time there is an increase in the requests for traits and qualifications that can be seen in relation with the recent change in the mission of the public libraries. Figure 3 shows an illustrative comparison of the development of library education being a requirement and the importance put on personal suitability for the position. The big city libraries stand out from the other municipalities, by trending ahead of the rest.

Discussion

Do these developments reflect that the profession of librarianship is about to lose its jurisdiction over the public library field? That was the overriding research question which we asked at the outset. Or in other words: Is the demand for candidates with a degree in library and information science reduced in the ten-year period between 2005 and 2015? Our findings seem to confirm that a significant reduction in the demand for library and information science educated librarians is taking place. For newly educated library and information science candidates with a preference for working in public libraries, it might seem promising that a generational shift is under way. Librarians who graduated in the first half of the 1980s are retiring, resulting in what one might term a veritable explosion in vacant positions between 2005 and 2015. However, the other side of the coin is that librarians must compete for these vacant positions with candidates coming from other educational backgrounds. Positions, which, 15, 20 or 25 years ago would have been reserved for librarians defined as graduates from library schools, are not so anymore. There is a tendency that employers are looking for candidates with an unspecified higher education, relevant education is the somewhat vague buzz term, while a greater weight is simultaneously given to personal and interpersonal traits, competencies and characteristics. The traits, competencies, and characteristics they ask for are relatively seldom related to professional experiences. Few advertisements ask for applicants with public library experience, rooted in the values and traditions of public libraries. Rather they ask for applicants who are change oriented, flexible, visionary, innovative, oriented towards new developments, i.e. characteristics describing a person inclined to leave traditions, present positions, and ways of doing things in favour of something new. A person who has completed a professional education has been trained to master a professional repertoire, a professional code of ethics and a perception of the profession’s social role and mission, such as formulated by Lankes (2016) in the quotation above. Such a professional ballast might be contrary to the adaptability and flexibility demanded in today’s rapidly changing working life.

There are, however, important modifications in our findings. The tendency to omit references to library education is first and foremost found in advertisements from Norway’s six largest cities, whereas large local government authorities defined as local government authorities with a number of inhabitants above 20 000 (Langørgen et al., 2015, p. 10) are the group of local governments where educated librarians are highest in demand, i.e. significantly higher than both in the smaller communities and in the big cities. This might reflect a situation where the big city libraries are in need of staff members with a specialised competence which librarians do not necessarily possess, whereas large local government authorities are in need of generalists who master all dimensions of librarianship, i.e. librarians.

Norway is now in the middle of a local government reform which will give fewer small local governments, and more local government authorities with inhabitants exceeding 20 000. The number of large cities will not be affected. This means a significant reduction in the number of one category of local governments with a tendency not to require library and information science education when recruiting librarians, whereas the number of the other category of local governments with the same tendency, i.e. the largest cities remain stable. The number of local governments with the highest tendency to specify library and information science education as a relevant qualification increases as a result of the reform. Is this good news for the librarians? Will it affect the demand for librarians in ways that are positive for graduates from library schools?

Conclusion

We do find clear indications that the demand for candidates with an educational background in library and information science has been significantly reduced from 2005 till 2015 when new positions in public libraries are being advertised. We also find an increase in the demand for personal and interpersonal traits which, contrary to specific experiences and competencies such as experience from public libraries or experience from mediation of literature, are very difficult to measure. The result might be that recruitment decisions are less transparent and more dependent upon the discretion of the decision maker than when formal education and specified experiences and competencies were more dominant. Combined the findings indicate that the profession of librarianship’s jurisdiction over the public library field is weakening. Further research with longer time series as well as comparative research to see if this a general trend is necessary to get a fuller understanding of the development.

About the authors

Beate Bjørklund holds a master’s degree in Management of Library and Information Institutions from Oslo Metropolitan University. The present article is based on her master dissertation from 2018. She is currently working as a librarian in California, USA. She can be contacted at beate.bjoerklund@outlook.com

Ragnar Audunson is a professor in Library and information Science at Oslo Metropolitan University. He received his master’s degree in political science from Oslo University, a diploma in librarianship for Oslo Metropolitan University and a doctoral degree in political science from Oslo University. He has researched and published extensively on library policies and the social role of libraries. He can be contacted at: ragnar@oslomet.no

References

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: An essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Adkins, D. (2004). Changes in public library youth services: a content analysis of youth services job advertisements. Public Library Quarterly, 23(3/4), 59-73. https://doi.org/10.1300/J118v23n03_10

- Audunson, R. (2015). Bibliotekarene - en profesjon under press? : institusjonalisering, deinstitusjonalisering og reinstitusjonalisering av et profesjonelt felt. [The librarians – a profession under pressure? : institutionalisation, deinstitutionalisation and reinstitutionalisation of a professional field.] In R. Audunson (Eds.), Samle, formidle, dele: 75 år med bibliotekarutdanning (p. 47-71). ABMMedia.

- Audunson, R., Hobohm, H-C. & Tóth, M. (2019). ALM in the public sphere: how do archivists, librarians and museum professionals conceive the respective roles of their institutions in the public sphere? In Proceedings of CoLIS, the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Ljubljana, Slovenia, June 16-19, 2019. Information Research, 24(4), paper colis1917. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1917.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191217173151/http://informationr.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1917.html).

- Beile, P. M. & Adams, M. M. (2000). Other duties as assigned: emerging trends in the academic library job market. College & Research Libraries, 61(4), 336-347. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.61.4.336

- Bratberg, Ø. (2014). Tekstanalyse for samfunnsvitere. [Text analysis for social scientists.] Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Danielsen, K., Egaas, M., Nygård, B. S., Undlien, A. K., Schøning, T. O. & Indergaard, L. H. (2014). Innspill til møte om folkebibliotek mandag 5. mai 2014. [Letter from library directors of the public libraries in the largest cities in Norway to Minister of Culture Thorhild Widwey]. Kulturdepartementets arkiv, (Sak 13/2960-10). Norwegian Ministry of culture.

- Gerolimos, M. & Konsta, R. (2008). Librarians' skills and qualifications in a modern informational environment. Library Management, 29(8), 691-699. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435120810917305

- Henricks, S. A. & Henricks-Lepp, G. M. (2014). Desired characteristics of management and leadership for public library directors as expressed in job advertisements. Journal of Library Administration, 54(4), 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2014.924310

- Kennan, M. A., Williard, P. & Wilson, C. (2006). What do they want?: a study of changing employer expectations of information professionals. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 37(1), 17-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2006.10755320

- Langørgen, A., Løkken, S. A. K. & Aaberge, R. (2015). Gruppering av kommuner etter folkemengde og økonomiske rammebetingelser 2013 [Grouping of municipalities by population and financial conditions 2013.] (Rapporter (Statistisk sentralbyrå : online), Vol. 2015/19.). https://www.ssb.no/offentlig-sektor/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/225199

- Lankes, R. D. (2016). The new librarianship field guide. The MIT Press.

- Lindstad, M. (2009). Nye krav til bibliotekarene. [New demands of the librarians.] Bok og bibliotek, 76(4), 12-16.

- March, J.G. & Olsen, J.P. (1989). Rediscovering institutions: the organizational basis of politics. Free Press

- Nasjonalbiblioteket. (no date). 2005-2012 Rådata. [2005-2012 raw data.] https://kunnskapsbase.bibliotekutvikling.no/statistikk/statistikk-for-norske-bibliotek/folkebibliotek/historisk-statistikk-for-folkebibliotek/ (Archived by WebCite® http://www.webcitation.org/784YxOBqx)

- Norway. Folkebibliotekloven. (1985). Lov om folkebibliotek (folkebibliotekloven). [Act relating to public libraries.] Retrieved from https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1985-12-20-108 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/784ZBbySa)

- Oslo kommune - kulturetaten. (2015, 15. september). Team Tøyen: Deichman søker fem nye medarbeidere. [Team Tøyen: Deichman seeks five new employees.] Retrieved 16. juni 2018 from http://bibforb.no/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Nytt-bibliotek-på-Tøyen-kun-for-barn-og-unge-Vi-trenger-deg.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/784aB6IJS)

- Østbye, H., Helland, K., Knapskog, K. & Larsen, L. O. (2013). Metodebok for mediefag [Method book for media studies.] (4. ed.). Fagbokforl.

- Ringdal, K. (2013). Enhet og mangfold: samfunnsvitenskapelig forskning og kvantitativ metode [Unit and diversity: social science research and quantitative method.] (3. utg.). Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget.

- Rognerød, E., Rasmussen, L. & Standal, S. (2014). To dårlige tapere? [Two bad losers?] Bibliotekaren, (1), 4-7.

- Svartberg Arntzen, J., & Svaleng, Ø. (2009). For mange bibliotekarer i norske bibliotek. [Too many librarians in Norwegian libraries.] Bok og bibliotek. https://www.bokogbibliotek.no/aktuelt/aktuelt/for-mange-bibliotekarer-i-norske-bibliotek (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3qQwKNj)

- White, G. W. (1999). Academic subject specialist positions in the United States: a content analysis of announcements from 1990 through 1998. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 25(5), 372-382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(99)80056-1

- Wise, S., Henninger, M. & Kennan, M. A. (2011). Changing trends in library and information science job advertisements. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 42(4), 268-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722241