Creating by me, and for me: investigating the use of information creation in everyday life

Lo Lee, Melissa G. Ocepek, and Stephann Makri.

Introduction. We investigate the use of information creation in everyday life, where individuals carry out various commonplace work. While there have been an increasing number of studies on information creation, little research exists on discussing its function and relationship to navigating life activities.

Method. To identify the ways information creation facilitates information tasks in the everyday world, we conducted two qualitative studies, each reflecting a particular aspect of our daily lives. We held semi-structured interviews and think-aloud observation in physical grocery stores and on the Pinterest website. A total of twenty-eight participants (eighteen grocery shoppers and ten arts and crafts hobbyists) were recruited for the two studies.

Analysis. Transcribed interview data and field notes were analysed inductively. We assigned and refined a series of codes iteratively to identify themes.

Results. Findings highlight a variety of circumstances in which participants made use of information creation as an end product to support their ordinary actions (in this case, grocery shopping and idea collecting, respectively).

Conclusions. This study gives an in-depth analysis of information creation, underlining its potential functions in efficiently and engagingly aiding the accomplishment of routine activities. We demonstrate the practical and affective value associated with information creation, expanding this concept in information behaviour research.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper891

Introduction

The repetitiveness of commonplace work can be banal and exhausting. Such daily activities usually demand a different degree of time and effort when people undertake them. Although the content of routine work is often predictable because of people’s familiarity with it, everyday situations can still vary based on the distinction of each individual and their environment. Giard (1998) provided a compelling interpretation of life activities when portraying the art of everyday cooking, noting that it is a creative practice requesting lively and ordinary intelligence. According to Giard, cooking requires people to be innovative and intelligent, as we have to take into account the variance of everyday life that makes each type of conventional cooking different. To figure out this seemingly predictable yet actually dynamic world, individuals need to interact with information to proceed with life (Savolainen, 1995; 2005). During this interactive process, people usually create and curate information resources that differ in form and nature to satisfy their needs (Linder, et al., 2014; Rosenbaum, 2011; Whittaker, et al., 2000). To this end, it is crucial to investigate the creation of information since it helps people navigate and accomplish life activities (Whittaker, 2011). An understanding of such information also provides a more holistic view of information behaviour, leading scholars to inspect information phenomena from a novel perspective that can then enrich research literature.

Research on information creation has become increasingly popular over the past decade both in and beyond information sciences (Gorichanaz, 2019). Among theoretical models and frameworks that address information creation from different perspectives, we build on Koh’s definition (2013) of information creation because of its broad and exploratory features. Koh explained that an information-creating behaviour is performed to fulfil a person’s information need. While prior studies have shown the occurrence of information creation in both work and educational settings, no research has been conducted to address such practice in a daily context, particularly regarding commonplace life activities. In our view, a repetitive daily event does not necessarily mean boredom; instead, it can be fun and personally meaningful. Using this lens, we aim to examine the vital role information creation serves in everyday life. We give a detailed analysis of each function of information creation that facilitates our everyday information tasks, demonstrating its potential in making this routine work efficient and engaging.

Before we move further, a description of our inclusion of the two studies on grocery shopping and idea collecting, and the commonalities and differences between these two activities may help readers better understand the design of this research. The main underlying commonality is that both grocery shopping and idea collecting are information-heavy and require people to be creative when undertaking them (Ocepek, 2016a). When taking part in grocery shopping and idea collecting, people not only consume but also create information to solve problems and make decisions. While grocery shopping typically occurs at regular intervals (Park, et al., 1989), idea collecting happens anytime and anywhere (Hemmig, 2009). Moreover, grocery shopping is essential in sustaining life, but people tend to collect ideas to satisfy high-level information needs, such as ideation, which usually results in intellectual content (Makri, et al., 2019). From these aspects, we argue that concurrently examining the two studies is reasonable and productive to fulfil our goal. Researching grocery shopping and idea collecting enables us to provide a thorough analysis of information creation, elucidating its richness in various everyday information phenomena.

To analyse information creation, we first clarify our adoption of the definition of information creation. We then discuss relevant literature about information creation, delving into the keeping-track behaviour and everyday ideation because of their close association with information creation. We regard information creation as a broad category that results from the keeping-track behaviour (e.g., documenting information) and everyday ideation (e.g., organising information). Qualitative methodology, findings, and discussion are also provided. We conclude the paper by discussing the significance of information creation in everyday life, illuminating how it offers a broader lens to study information behaviour.

Clarification of concept

Koh (2013) articulated that ‘information-creating behaviour can be defined as the way people create messages, cues, and informative content that can be used to meet the existing or potential information needs of the creator or other users’ (p. 1827). For this study, we based our definition on Koh’s knowledge, and consider information creation to be any physical or virtual items produced by people that can influence information behaviour. We would like to stress the outcome of information-creating behaviour, that is, the usage of information utilised to create new information. We prefer this facet of information-creating behaviour over its processual perspective in an attempt to examine how created information has helped individuals tackle daily tasks by making them efficient and pleasant.

Background

Researchers from diverse disciplines have proposed and discussed different theoretical models when examining information creation. These include those scholars from information studies, education, media and documentation, communication, and human-computer interaction (Gorichanaz, 2019). People may not always use the terms of information creation or information-creating behaviour while referring to the same concept. For instance, when describing the behaviour of externalizing undertaken by game designers during their project design, Makri and colleagues (2019) defined it as ‘Expressing ideas generated during information acquisition in external form to support idea evaluation and drive further idea development’ (p. 780). What Makri and colleagues pointed out here as an external form is close to information creation discussed in this paper because externalizing is established to support a high-level intellectual information task.

In the same vein, when describing a framework for technology design, Shneiderman (2000) defined the create stage as ‘Explore, compose, and evaluate possible solutions’ (p. 120). Building on this concept, Shneiderman further suggested eight activities for supporting user interfaces, within which four fell under the create stage. In a serious leisure context, Hartel and colleagues (2016) made use of the term ‘dress’ in Hektor’s (2001) model of information behaviour to conceptualise the output of information, arguing that ‘people can be capable, productive, prolific creators and distributors of information, too’ (Hartel, et al., 2016; Part 2, para 10). In a school context, Trace (2007) connected, by using the same term, information creation to document work in the classroom setting. Trace found that the creation of information is strongly influenced by people’s acquired knowledge and their experiences gained by interacting with others. McKenzie and colleagues (2014) upheld this argument, depicting that even in the household, information created to keep track of daily life is affected by managerialism and embedded in an organizational context. A similar result is also found in a recent study on beauty and lifestyle YouTubers by Thomson (2018). Grounded on empirical data, Thomson noted that YouTubers were in an expansive social world where the interaction between different actors would affect the video creating process.

Switching from the adult population, Koh (2013) targeted youths’ online deliberate information creation on using a graphical programming language, Scratch. In particular, she aimed to discuss ‘informative projects that are meant to be useful in meeting one’s information needs’ (p. 1827). By doing so, Koh elucidated the general process of information-creating behaviour, including the development of content, organisation, and presentation of information. She also discerned three patterns in the creating episode: visualizing, remixing, tinkering, as well as an affective aspect showing a sense of accomplishment. As stated in the previous section, we rest on Koh’s definition of information creation due to its explicit and exploratory features.

The keeping-track behaviour

Compared with literature on online information creation, few studies have been conducted to address the physical creation of information. For example, research on the keeping-track behaviour helps widen the discussion as individuals rely on various tools and means to produce everyday information (McKenzie and Davies, 2012). People keep track of different things both to manage their time and effort across contexts, as well as to ‘remind themselves and others of what must be done and when, where, and by whom’ (McKenzie, et al., 2014, Introduction, para 1). In the workplace, people have different systems to keep track of work progress (Im, et al., 2005). In the household, individuals coordinate their life events with numerous documentary tools and organising systems, such as calendars, recipe books, and rosters for school or volunteer work (Kalms, 2008; McKenzie and Davies, 2012; Taylor and Swan, 2005). Individuals also keep track of their life at home by creating a variety of records, including check-ins, status reports, lists, and reminders. McKenzie and Davies regarded these records as genre systems connecting people, tasks, time, and places. By making internal information external, genre systems illustrate how connections in the household are shared and interacted with by individuals and institutions outside of home. This keeping-track behaviour enables people to keep things organised and complete tasks without those tasks interfered with other mundane matters.

Everyday ideation

Information creation embodies everyday ideation. Studies of ideation provide information behaviour researchers with a context to probe information acquisition and use (Makri, et al., 2019). Information-based ideation refers to the activities that individuals use to form new ideas to express creativity and innovation (Kerne, et al., 2014). In the everyday world, people usually construct new meanings for objects, which concurrently reflect the idea of everyday design, which refers to activities that ‘we all take part in and one that helps us negotiate our daily lives’ (Wakkary and Maestri, 2007, p. 163). For instance, in the household, people create new functions for furniture by repairing or reusing them (Maestri and Wakkary, 2011).

Blending information-based ideation and everyday design, Linder, Snodgrass, and Kerne (2014) established the concept of everyday ideation. Everyday ideation motivates individuals’ ongoing processes in which people seek, return, and organise what they have for practical and conceptual needs. It usually occurs on digital information platforms like Pinterest, Twitter, and Facebook, where individuals create content for various reasons (Lindley, et al., 2013). For example, users shared their work on social media and posted content for consumption in the moment. People repurpose these digital information environments, making secondary use of the system meaningful to their personal lives (Syn and Sinn, 2015). Throughout our research, we expand on the discussion of information creation beyond personal documentation, examining how such creation contributes to the accomplishment of everyday information tasks.

Previous literature has offered a broad understanding of information creation. It yields remarkable insight into the occurrence of information-creating behaviour at work, beyond work, and in online environments. Nonetheless, there has been relatively little discussion on the end result of such behaviour and its immediate influence on a specific routine task. Thus, we are prompted to ask the research question of this paper: how do people utilise information creation to cope with everyday life tasks? We examine the utilisation of created information by shoppers and hobbyists in a daily context, identifying its potential function in facilitating everyday information tasks.

Methods

We conducted two qualitative studies to better understand the ways information creation is utilised in an everyday life context. The first study, which involved grocery shoppers as participants, investigated grocery shopping as a commonplace activity filled with complex decision-making processes and fertile information sources, such as labels, in-store signs, and price tags (Ocepek, 2016a). The second study, which involved arts and crafts hobbyists as participants, probed the everyday idea collecting process in which individuals navigated a creative website, Pinterest (pinterest.com). Both studies included a combination of semi-structured interviews and think-aloud observation. All participants were over eighteen and were recruited with emails, flyers posted in public places, and personal contact. To protect confidentiality, we removed all participants’ names and identifiable information from transcripts. We assigned pseudonyms to each participant by using a random name generator based on U.S. census data delineated by gender. Table 1 lists all pseudonyms by study and site.

| Study | Participants |

|---|---|

| Grocery shoppers | Alberta, Arturo, Carole, Gina, Glen, Henrietta, Jenna, Joseph, Julius, Katie, Leah, Lorraine, Mabel, Michelle, Patsy, Robin, Tonya, and Wilma |

| Arts and crafts hobbyists | Derick, Elisa, Iris, Karl, Lorene, Mia, Nikki, Ruth, Savina, and Sophia |

Data collection

The first study involved interviews and shopping observation with eighteen people who love food or grocery shopping at a physical shopping location of their choice. A total of seventeen grocery shoppers participated in both an interview and observation, while one only participated in an interview. In the interview session, participants were asked about their general experiences of food and grocery shopping. Interview questions included but were not limited to, how do you feel about food and grocery shopping; what stores do you like to grocery shop at; do you shop with other people?

The second study involved interviews and observation with ten arts and crafts enthusiasts, where they showed us how they used Pinterest. In the pre-interview session, we asked participants about their interests in arts and crafts. Interview questions included but were not limited to, how long have you been interested in arts and crafts; what kind of arts and crafts do you usually do; where do you usually visit to seek information about arts and crafts? The interview portion included a post-interview, which aimed to understand how the outcome of information-creating behaviour evolved and influenced everyday creative tasks of participants. A total of seven arts and crafts enthusiasts participated in the entire session, while three missed the post-interview portion due to availability issues.

All interview and observation data are included in this work. Because the present work depicts part of a larger project on everyday information behaviour, no interview question directly asked participants about their usage of information creation. However, since we requested participants to verbalize their actions when navigating grocery stores and Pinterest, we got practical examples of information creation, including elaborations of participants. For example, when seeing a participant took out her shopping list, we asked, how much time do you spend planning and preparing the list outside of the grocery store? Likewise, when witnessing a participant pinned a picture to his Pinterest board, we asked, why do you pin that to your board?; how do you plan to use those pins? Such an approach is beneficial for capturing information creation, whose occurrence can be hard to anticipate and operationalize accordingly when designing the research.

Data analysis

Each interview and observation were audio-recorded and transcribed. To better capture participant actions, we took notes during each observation and used them to complement our audio data. We analysed the qualitative raw data collected with the data analysis software, Atlas.ti. We applied bottom-up thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) to identify information-creating behaviour and information creation based on Koh’s definition (2013). For example, when coding the data showing that a participant created a list and used it happily during grocery shopping, we labelled this segment of text with broad codes, such as creation, function, and feeling. While having a constant comparison between each code, we put together codes to identify potential relationships between these initial codes. For instance, when looking through the texts labelled with creation and function, we saw that numerous participants mentioned they used lists to guide their shopping trips. Hence, we assigned a new code creating lists as guidance, which thematically encompassed the content of previous codes. In a similar vein, when looking at cases of participants learning by reviewing information gathered on Pinterest boards, we generated a new code creating boards to learn to grasp the content of relevant codes thematically.

Findings

The participants described different approaches to their use of information creation in everyday life. We identified two key information creation, lists and boards, which participants generated to tackle daily jobs. To support these commonplace activities, including grocery shopping and idea collecting, participants went through the process of selecting, organising, and adding value to information, therefore making their creation of information meaningful. Information creation was stored in various physical and digital spaces (e.g., on paper, apps, or the Internet). The usage of information creation suggests that participants repurposed such information to address different needs than those they sought to satisfy when producing the information originally.

List making

List making is a prevalent everyday information behaviour that illustrates shoppers’ deliberate information creation for grocery shopping. At grocery stores, people typically make decisions, such as comparing prices between different stores or selecting items that not only meet their needs but also are on sale (Ocepek, 2016b). As grocery stores are full of information, shoppers usually rely on multiple information sources to help them stay on the right track. One of the strategies that people employ to maintain organised is by making shopping lists. All participants of the first study mentioned their use of shopping lists, although they served different functions for each shopper. The most common function is guiding their shopping. For example, Lorraine, a working mother who often shops with her two young children, created a list to guide her in the grocery store in case she got distracted and missed something.

Lorraine: Someone will start melting down in an aisle and I’ll have the screaming kid in the grocery store, so I try to put it in sections. So, if I don’t get to a section, maybe somebody can come back later.

Interviewer: So, the list is really in two parts?

Lorraine: Yeah. One is the what we’re going to eat for the dinners and then what we need to buy at the grocery store. There are a few things on here for lunch, but my kids eat lunch at school.

Interviewer: Okay. And why did you bring both parts?

Lorraine: Oh, just so I can remember what I’m cooking in case I forgot something or I’m like why did I need this? Oh yeah, it’s because I’m making ... I don’t know. Something on this day or that day.

Mabel shared a similar view that having a list enabled her to quickly determine which section or store she should go to find specific items. Detailed quantity and store information in the list expedited Mabel’s shopping and saved her time. Additionally, list making allowed Mabel to navigate the large grocery stores without feeling overwhelmed.

Mabel: I just want to get in, get out. I have my list; I even have it sorted by sections. If I have to go to multiple [stores], I have that sorted by which one I’m going to. I know exactly what I need to get and I leave. That’s it. I even write down the quantity; if I need two jugs of milk, I will write down “two” next to it so then I don’t have to think about it while I’m there.

Mabel is a bargain hunter who always tries to find good deals, stating that she paid attention to prices and ‘always keep[s] a mental book for [the prices]’. To Mabel, making a list for various stores is useful for comparing prices and to ensure efficiency, for which she constantly strives. Mabel’s thriftiness comes from a time when she had to save money and learned tips to do so.

Mabel: I think it all stemmed from me being poor. Also, speaking of me being poor, I think that’s why I stick so closely to the list, because I read in a book somewhere that if you want to save money at the grocery store, you write a list of exactly what you need, and you stick to that list, and you do not deviate from that list, because they put all kinds of extra stuff here to make you want to buy it.

In Lorraine and Mabel’s cases, they organised their shopping lists of what they planned to buy before the trips and utilised them as guidance in the stores. Having a list in hand helped participants plan which direction they should go for potential products (e.g., if many items on the list were chilled foods, they went that aisle first). A shopping list also serves a role in projecting the shopper’s personal belief, such as Mabel’s pursuit of efficiency and money-saving ideas.

Another common usage of a shopping list is reminding participants of the items to buy. This role is different from the previous guidance role because here participants used lists to check items rather than to navigate stores. One representative example comes from Lorraine’s shopping-trip observation. When describing her habit of organising a list into parts, Lorraine indicated she brought two different versions of the list (by section and by meal) to the store that day: ‘Just so I can remember what I’m cooking in case I forgot something or I’m like why did I need this? Oh yeah, it’s because I’m making ... I don’t know. Something on this day or that day’. Moreover, the format of shopping lists varies. Unlike Lorraine, who used a physical list, Katie created her list electronically.

Katie: I made a list today, but it’s in my notepad on my iPhone. I think I kind of have an idea, but I’ll probably just check it at the end to make sure or in the middle if I’m worried that I’m not getting everything.

In the arts and crafts enthusiast study, making lists is not as prevalent as in the grocery shopper study. Instead, the enthusiasts often made boards to gather and organise their ideas and to spark their creativity, which will be discussed further in the next section. We only identified one mention of list-making from hobbyist participants. Elisa has been a scrapbooker for more than forty years and enjoys taking various do-it-yourself classes. She shared her list-making practice during the observation by pinning numerous recipes based on her cooking plans and preferences (On Pinterest, individuals can pin images that they find interesting and organise them into thematic boards). In the interview, Elisa explained the motivation behind her habit of reusing pins for grocery shopping.

Interviewer: How do you keep and use these recipes?

Elisa: Well, I pinned it on there, and then I saved it. But sometimes I like to print them out because then when I go to the grocery store, I have like the list of what I need. Or sometimes I can just put it on my phone. I’m like, I’m not gonna lose it. And it’s gonna be like right there ...

In Lorraine, Katie, and Elisa’s cases, rather than using lists as guidance to navigate grocery stores, the three participants considered lists to be reminders, enabling them to recall what specific ingredients they would like to buy, such as the one in their meal plans.

The last non-traditional usage of a shopping list is managing impulse purchases. One example we found regarding this kind of use is from Joseph, who explained how he included four spaces in his shopping list to limit the number of impulse buys.

Joseph: The only other strategy we use is we understand that sometimes there are impulse buys. We do four lines on the list. That’s the only impulse items we will buy, we allow ourselves four. It has to be a real good reason, like, if prime rib suddenly dropped down to a buck a pound, we’d have to think about that.

Interviewer: That’s very systematic for impulse buys.

Joseph: Yes. We believe in clearly defined, rigidly outlined spontaneity.

In this case, a shopping list helped Joseph stop and think before making an impulse buy. By conceiving of a good reason for an unplanned purchase, Joseph turned an impulse buy into a rational decision that was no longer driven by emotions. This practical value enabled Joseph’s information creation to be meaningful when he shopped.

Board making

Designing a board is a common creating behaviour in everyday life. The concept of digital boards on Pinterest comes from mood boards used by visual designers to collect, organise, and annotate visual media, such as images and video, in a practical form (Makri, et al., 2019). These media are referred to as pins on Pinterest. To individuals who enjoy making arts and crafts, Pinterest is an ideal platform on which to select images and create boards to collect information for everyday ideation (Linder, et al., 2014). The way individuals select and organise pins gives rise to the production of Pinterest boards as information creation. In the arts and crafts enthusiast study, nine participants either built Pinterest boards during observation or discussed their habits of creating them in the interviews. The most prevalent use of these boards is to spark inspiration. For example, as a creative person who always develops new interests in arts and crafts, Iris described her positive experiences of using Pinterest.

Iris: I think it’s [Pinterest] very easy. And it is perfect for me, because I can pin things and go back to it. It’s a great place to be able to do that cause I have different boards for different things. I can usually easily find stuff when I need to go back to it.

During her observation, Iris stated that she would like to find ideas for housewarming home décor projects. At first, she only focused on relevant pictures of décor examples. However, we noticed that later on, Iris seemed to collect things beyond her initial purpose. When asked about her reuse of pins collected at the time of the study, Iris reported that ‘when I get ready to do the project, I’ll pull up the boards that I pin those to and just to kind of look and get more inspiration’.

Iris was not the only participant who used Pinterest boards as information creation to seek inspiration. Karl, who has enjoyed drawing since he was little and currently works in computer graphics, had a similar practice. As a bird-lover who keeps two budgies at home, Karl spent much of his observation seeking images of birds. Karl explained he was specifically interested in finding pictures that included details of a bird’s wings because he was not good at drawing wings. After pinning numerous artistic images of birds on Pinterest, Karl expanded the scope to include images of birds beyond drawings (mostly photographs of birds). The participant stated he did so because photos sparked his interest and he liked his encounters with unexpected information from using the following function on Pinterest: ‘I guess after this ‘Following’ something at certain points, you’ll sometimes find things that you didn’t think you were looking for, but you want to look at it’.

In contrast to Iris and Karl, Ruth mentioned that she thought Pinterest boards often did not work for her. As a maker who has quilted since the third grade enjoys making doll clothes, Ruth described the way her pinning behaviour changed over time. Unlike most arts and crafts enthusiasts, Ruth only went to Pinterest to seek specific materials that could be used immediately: ‘I know some people make like Pinterest boards, just like idea boards with lots of pictures, sort of brainstorming, but I mostly use it to get to the actual patterns’. During the observation, Ruth stated that she would like to search for ideas about Halloween decorations on Pinterest. Throughout her exploration, the participant did not pin anything and only focused on pictures with detailed instructions. In the interview, Ruth showed us all her Pinterest boards, which had been built over six years but which she no longer updated.

Interviewer: Do you usually like to pin pictures in your boards?

Ruth: I used to do more, like I would make boards for each Christmas. We usually try to have a theme, and so I would make a board for each Christmas. I have not done that in a while, because it kind of makes me feel like, there’s a lot, there’s so much you could do when you didn’t get any of them done. I have a lot of works in progress and projects going on, so I try not to add more ideas of things I can do.

Ruth did not make new boards (or pin new images to any existing boards) due to the large amount of stored information that she had not yet consumed. Seeing her current boards on Pinterest reminds her of projects she plans to do before she adds any more new pins.

Another common usage of a Pinterest board is to help participants gain new knowledge. For example, Sophia is a lifelong learner who keeps trying new arts and crafts. During observation, we noticed that Sophia tended to pin pictures from which she could acquire new skills, such as how to fix ugly yarn and how to use vinegar to make the dye hold. In the interview, Sophia described her habit of revisiting pins to guide her craft-making by comparing pins to online recipes.

Sophia: I’ll definitely go back and look [pins] later. It’s kind of like I bookmark a website for recipes. I do go back to that website later and go through the recipes. If I have something in mind I want to make, but I don’t seem to have any recipes for it, I’ll go through my bookmarks. So yeah, I’ll definitely go back and look through them [pins].

In the same manner, Nikki is an art lover who makes jewellery and does fabric work. During Nikki’s observation, we noticed she often clicked on pictures illustrating new techniques, such as how to knit socks or small things. She explained that by looking at images on Pinterest, she could improve her arts and crafts skills. While Nikki did not pin anything during her observation, she bookmarked useful pages to print later.

The last non-traditional usage of a Pinterest board is soothing participants’ emotions. In the arts and crafts enthusiast study, participants occasionally mentioned that they collected relaxing pins to comfort themselves. For example, as a person who would like to adopt a minimalist lifestyle, Savina usually went to Pinterest to see what other minimalists do: ‘I have like a minimalism thing [board], because I’m sort of getting into minimalism, and then I wanted to look at examples of that. Hopefully would be inspired by it’. In this example, Savina is similar to Iris and Karl because all used Pinterest boards to seek inspiration. In addition to pinning pictures exhibiting an ideal lifestyle, we noticed that Savina also liked pinning images of beautiful scenery.

Savina: So I would like to hold these things [pictures] into Aesthetics [board]. These are like the kind of pictures that I would put in there. Just as like, things that will make me happy and make me feel calm for later on.

As well as the Aesthetics board, Savina said she had another board where she put many motivational quotes to inspire her when feeling upset. According to the participant, Pinterest plays a key role in brightening her mood.

Discussion

In this section, we elaborate on our findings to discuss the overarching research question: how do people utilise information creation to cope with everyday life tasks? In the grocery shopper study, people utilised information creation as an end product to navigate the stores, remind them of items to buy, and introspect before making the purchase. In particular, when grocery shoppers applied information creation as navigators, they displayed two sub-features of such information: it was shareable and could project a personal belief. Likewise, in the arts and crafts enthusiast study, individuals employed information creation as a tool to ideate, learn, and lighten the mood. Table 2 shows each function of the outcome aspect of information creation found in the study. We also match each function with the names of participants mentioned in the previous section in Table 2.

| Function of information creation | Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| To navigate information spaces | Shareable | Lorraine |

| Personal belief projector | Mabel | |

| To remind | Lorraine, Katie, and Elisa | |

| To introspect | Joseph | |

| To ideate | Iris, Karl, and Savina | |

| To learn | Sophia, Nikki | |

| To comfort | Savina | |

First, this research reveals that the most common function of information creation is to help grocery shoppers navigate information spaces. Lorraine and Mabel’s cases of using shopping lists to navigate the store layout reflect the definition of lists in McKenzie and Davies’ (2012) research as, ‘promises of things to do, items to acquire or a combination of the two’ (p. 445). To our surprise, this function usually occurs twofold in the present work. At a practical level, participants brought shopping lists to the grocery stores to quickly locate what they sought. At the other level, shopping lists serve as more than guides; they are tailored to meet the condition of each household. Building on the definition of lists, we would like to demonstrate the personal value, beyond their utilitarian aspect, can influence participants’ information experiences at grocery stores. To Lorraine, her shopping list served not only as a personal aid but also as a tool shared by her husband to accomplish the task. In McKenzie and Davies’ (2012) study, they drew maps that showed how genre systems, including lists, built social relations with people and tasks. Though Lorraine may be unaware of it, her list supports the social context of a domestic task: that either Lorraine or her husband could do the shopping by using the same list. Similar to Lorraine, Mabel developed a list that carried dual meanings: a personal aid for navigation and a tool to project personal belief. Other than using the list to document items, which follows the earlier definition, Mabel utilised it to compare prices across stores, putting her money-saving and efficiency beliefs into practice. Mabel’s example shows how her memories and lived experiences of the past shape information creation (Krikelas, 1983), making such information unique and irreplaceable in the everyday world.

This research also suggests that created information can be used as reminders. Lorraine, Katie, and Elisa’s cases of applying shopping lists to remind them of plan-to-buy products aligns with the definition of reminders: such objects are ‘to oneself or someone else about something that had to be done’ (McKenzie and Davies, 2012, p. 445). Under this definition, we highlight the fact that Elisa used the Pinterest system for more than creative ideation and personal history documentation (Linder, et al., 2014; Syn and Sinn, 2015). After gathering and saving possible recipes on Pinterest, the participant either printed them out or put them on her phone for her shopping trip. By selecting, organising pins online, and utilising them offline as shopping lists, Elisa optimized the function of information creation, underscoring its potential to transfer between online and offline settings. This is an excellent example of making digital information useful in the physical world by using it to support everyday tasks.

The way people make a shopping list can meanwhile embody creativity in everyday life. Such a creative practice is manifested in Joseph’s case, who created an original and useful—the two basic components of creativity (Runco and Jaeger, 2012)—list for grocery shopping. The distinctive utilisation of Joseph’s list in not only helping him to remember what to buy, but to also lead him to pause and reflect on unnecessary information from potential impulse purchases sheds new light on existing literature. Without an innovatively compiled list, Joseph might have found it hard to avoid impulse buys. Here, information creation is not merely a collection of information; instead, it lets people stay organised and efficient in potentially overwhelming information environments like grocery stores.

Beyond the context of grocery shopping, this research illustrates the frequent occurrence of relying on information creation as a tool to ideate in leisure activities. In Iris and Karl’s cases, the creation of Pinterest boards facilitated creative ideation. The participants browsed the websites, picked helpful pins, and arranged them into boards for later use. This finding is consistent with prior literature, which showed that users organised Pinterest boards for both practical and emotional reasons (Linder, et al., 2014; Lindley, et al., 2013). It also supports previous researchers in personal information management (PIM) who argued that people organised information for possible reuse in the future (Jones, 2012; Narayan, 2014; Whittaker, 2011). We advance such discussion by noting the benefit of unexpected but exciting information (known as information encountering, Erdelez and Makri, 2020) in information creation and its influence on everyday idea collecting. In Karl’s example, by typing in a broad keyword, he received various drawing ideas about birds beyond his initial target, wings. To Karl, his serendipitous encounters of pictures showing birds’ cheeks, feathers, and poses served as inspiration for future creation, enriching his hobby.

In addition, the arts and crafts enthusiast study found the function of learning when people apply information creation on Pinterest to everyday life. Sophia and Nikki’s cases of learning through the Pinterest boards display the illuminating value of information creation and exhibit different means of storing information. Both were aiming to learn, but Sophia preserved what she felt informative on Pinterest boards, while Nikki saved it on her laptop. This finding supports previous research, showing that Pinterest was a platform attracting individuals with various pictures and teaching them new knowledge about their interests (Linder, et al., 2014). Sophia and Nikki’s cases demonstrate how participants attached the function of learning to their creation of information, with the purpose of sharpening their skills for future creative projects.

An assortment of content on Pinterest offers people an emotional outlet. Savina’s example of using Pinterest boards to record lifestyle ideas aligns with prior literature about ideation by which people form ideas to address practical needs (Linder, et al., 2014; Thomson, 2018). In Linder and colleagues’ research, they also found Pinterest’s emotional value originated from individuals’ memorable content preserved on it. However, rather than describing this type of content, we suggest that Savina regarded Pinterest boards as immediate sources to overcome frustration in her daily life. Savina’s creation of information on Pinterest was personally meaningful because she could use these instant resources to soothe her emotions. In contrast to Ruth, who found Pinterest boards overwhelming, Savina embraced the affective value of information creation. This finding indicates the significant outcome of information-creating behaviour in the affective dimension, revealing its positive influence on handling negative feelings.

Although information creation seems to play a positive role throughout this research, we still identified an example in which the participant did not actively take advantage of created information. This instance is Ruth in the arts and crafts study, and her changing attitude to Pinterest boards and the pinning action. This result expands on the previous literature about everyday ideation by exhibiting the behavioural evolution of individuals’ creating practices and possible reasons behind it. Ruth’s feeling of being overwhelmed kept her from revisiting her created sources of inspiration. This negative emotion resulting from information creation is an example of the dark side of information behaviour (Bawden and Robinson, 2009), since it can hamper the collection and evaluation of new ideas, potentially stifling creativity.

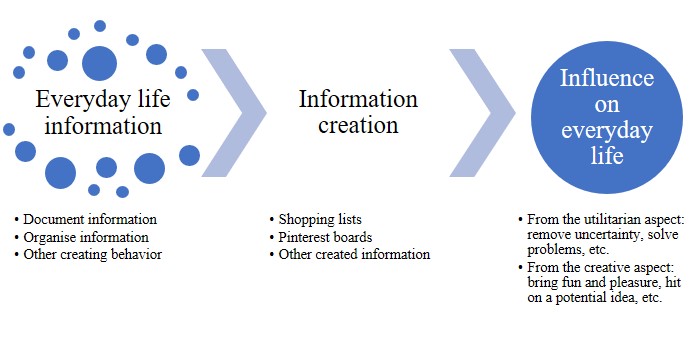

Lastly, using the perspective of information creation to address everyday life tasks is different from examining the same phenomenon from the aspect of PIM or documentation. Figure 1 shows our understanding of information creation that considers angles offered in prior literature. By incorporating the concept of information creation, we stress the lively and idiosyncratic character of information beyond its utilitarian dimension. For instance, other than responding to the spirit of getting things done in PIM (Jones, 2012), information creation also brings people fun and pleasure during the process. Moreover, although using the documentation angle to discuss everyday life tasks is applicable, it may not concurrently capture personal values and the social influence attached to everyday information creation. The prevalence of information in daily life does not simply involve people in a series of consumption behaviour like acquiring and maintaining information. Instead, it triggers the practice of creating something new to fit individual life in contemporary society. According to our empirical data, such information creation helps the everyday world become intriguing and refreshing.

Limitations

Three limitations are identified in this exploratory research. First, as mentioned in the data collection section, we did not ask specific questions related to development, organisation, or presentation of information creation because these only emerged as explicit themes after conducting the studies. Nonetheless, using the think-aloud technique enabled us to ask people to elaborate on their created information during the observation. Second, we focused on Pinterest as the only website that hobbyists used in the arts and crafts enthusiast study, limiting our outlook on other forms of information creation in everyday life. Third, we do not know how far our examples from these two task types (grocery shopping and idea collecting) can be generalized to other kinds of commonplace information activities.

Conclusion

This study investigated information creation in daily life through interviews and observation of two everyday activities: grocery shopping and idea collecting. We found that information creation supported these tasks in multiple ways, including spurring creative inspiration and making them more efficient and delightful. For example, by compiling a thorough shopping list, participants helped themselves and their family members save time and effort. A list was also essential in projecting personal beliefs and preventing irrational impulse purchases, by having shoppers reflect before they absorbed too much information. In the same vein, by creating a fertile Pinterest board, participants recorded a vast amount of thought that could be recombined to fulfil a variety of future creative needs. A board could also aid hobbyists in learning and coping with disappointment.

The findings throw new light on information creation, showing the various circumstances in which participants created information to advance their commonplace life tasks. For instance, beyond acting as documentation tools (Syn and Sinn, 2015), Pinterest as a digital information environment enables the invaluable creation of information in addressing people’s affective demands. In many cases, information creation is used to encourage inspiration and creativity through the generation and development of new ideas. However, information creation can have a dark side. It can make people feel overwhelmed, keep them from revisiting created sources, and possibly inhibit creativity. This enriched understanding of information creation provides a more critical lens to study human information behaviour.

Future work can examine the following aspects of information creation. First, as described in the limitation section, Pinterest was the only platform where we examined arts and crafts hobbyists’ information creation. To this end, we recommend investigating why individuals produce or exploit information on other platforms, such as TikTok. Second, future researchers may consider examining long-term usage of information creation across a variety of everyday life situations to better understand how it can make routine work more effective, efficient, enjoyable, creative, or innovative. Third, the influences of demographic variables on information-creating behaviour should also be studied, since sociocultural factors are complicated and may generate completely different results. Such an exploration will be beneficial in enhancing the comprehension of information creation, striking up a more diversified conversation outside of information-related fields.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank anonymous reviewers for giving constructive feedback on our paper. We would like to extend our gratitude to Dr. Kyungwon Koh in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for sharing her remarkable insight about our early draft. This research project was partially supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services grant RE-02-12-0009-12, awarded to researchers at the University of Texas at Austin, School of Information. This work was also supported by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

About the author(s)

Lo Lee is a PhD Candidate in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research interests primarily include information behaviour, arts and crafts, and everyday creativity. She can be contacted at lolee2@illinois.edu

Melissa G. Ocepek is an Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in the School of Information Sciences. Her research interests include everyday information behaviour, critical theory, and food studies. She can be contacted at mgocepek@illinois.edu

Stephann Makri is an academic in the field of Human-Information Interaction, based at City, University of London. His research involves gaining a rich, qualitative understanding of important but under-researched aspects of Human Information Behaviour and considering the implications of this behaviour for the design of novel digital information environments. Previous research in this area has involved understanding serendipitous information encountering, the role of gratitude in online communities and the role of information in facilitating view change. He can be contacted at stephann@city.ac.uk

References

- Bawden, D. & Robinson, L. (2009). The dark side of information: overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551508095781

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Erdelez, S. & Makri, S. (2020). Information encountering re-encountered: a conceptual re-examination of serendipity in the context of information acquisition. Journal of Documentation, 76(3), 731-751. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-08-2019-0151

- Giard, L. (1998). The nourishing arts. In M. de Certeau, L. Giard & P. Mayol (Eds.). The practice of everyday life (Vol. 2: living and cooking, pp. 151–170). University of Minnesota Press.

- Gorichanaz, T. (2019). Information creation and models of information behavior: grounding synthesis and further research. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(4), 998–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769968

- Hartel, J., Cox, A. M. & Griffin, B.L. (2016). Information activity in serious leisure. Information Research, 21(4), paper 728. http://informationr.net/ir/21-4/paper728.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6m5H6PUqm)

- Hektor, A. (2001). What's the use?: Internet and information behavior in everyday life. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Linköping University.

- Hemmig, W. (2009). An empirical study of the information-seeking behavior of practicing visual artists. Journal of Documentation, 65(4), 682–703. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410910970302

- Im, H.-G., Yates, J. & Orlikowski, W. (2005). Temporal coordination through communication: using genres in a virtual start-up organization. Information Technology & People, 18(2), 89–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593840510601496

- Jones, W. (2012). The future of personal information management. Part 1, Our information, always and forever. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. https://doi.org/10.2200/S00411ED1V01Y201203ICR021

- Kalms, B. (2008). Household information practices: how and why householders process and manage information. Information Research, 13(1), paper 339. http://informationr.net/ir/13-1/paper339.html

- Kerne, A., Webb, A. M., Smith, S. M., Linder, R., Lupfer, N., Qu, Y., … Damaraju, S. (2014). Using metrics of curation to evaluate information-based ideation. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 21(3), 14–48. https://doi.org/10.1145/2591677

- Koh, K. (2013). Adolescents’ information-creating behavior embedded in digital media practice using scratch. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(9), 1826–1841. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22878

- Krikelas, J. (1983). Information-seeking behavior: patterns and concepts. Drexel Library Quarterly, 19(2), 5–20.

- Linder, R., Snodgrass, C. & Kerne, A. (2014). Everyday ideation: all of my ideas are on Pinterest. Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2411–2420. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557273

- Lindley, S. E., Marshall, C. C., Banks, R., Sellen, A. & Regan, T. (2013). Rethinking the web as a personal archive. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on World Wide Web, 749–760. https://doi.org/10.1145/2488388.2488454

- Maestri, L. & Wakkary, R. (2011). Understanding repair as a creative process of everyday design. Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Creativity and Cognition, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1145/2069618.2069633

- Makri, S., Hsueh, T. L. & Jones, S. (2019). Ideation as an intellectual information acquisition and use context: investigating game designers’ information-based ideation behavior. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(8), 775-787. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24169

- McKenzie, P. J. & Davies, E. (2012). Genre systems and "keeping track" in everyday life. Archival Science, 12(4), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-012-9174-5

- McKenzie, P. J., Davies, E. & Williams, S. (2014). Information creation and the ideological code of managerialism in the work of keeping track. Information Research, 19(2), paper 614. http://InformationR.net/ir/19-2/paper614.html

- Narayan, B. (2014). Information organising behaviours in everyday life: an exploration using diaries. In Du, J. T., Zhu, Q. & Koronios, A. (Eds.). Library and information science research in Asia-Oceania: theory and practice (pp. 24–44). IGI Global.

- Ocepek, M. G. (2016a). Shopping for sources: an everyday information behavior exploration of grocery shoppers’ information sources. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology,53(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301134

- Ocepek, M. G. (2016b). Everyday shopping: an exploration of the information behaviors of grocery shoppers. (University of Texas at Austin Ph.D. dissertation)

- Park, C. W., Iyer, E. S. & Smith, D. C. (1989). The effects of situational factors on in-store grocery shopping behavior: the role of store environment and time available for shopping. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 422–433. https://doi.org/10.1086/209182

- Rosenbaum, S. (2011). Curation nation: how to win in a world where consumers are creators. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Runco, M. A. & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092

- Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: approaching information seeking in the context of "way of life." Library & Information Science Research, 17(3), 259–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(95)90048-9

- Savolainen, R. (2005). Everyday life information seeking. In K. E. Fisher, S. Erdelez & L. McKechnie (Eds.). Theories of Information Behavior (pp. 143–148). American Society for Information Science and Technology.

- Shneiderman, B. (2000). Creating creativity: user interfaces for supporting innovation. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7(1), 114–138. https://doi.org/10.1145/344949.345077

- Syn, S. Y. & Sinn, D. (2015). Repurposing Facebook for documenting personal history: how do people develop a secondary system use?. Information Research, 20(4), paper 698. http://InformationR.net/ir/20-4/paper698.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6cduRMqye)

- Taylor, A. S. & Swan, L. (2005). Artful systems in the home. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 641–650. https://doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1055060

- Thomson, L. (2018). "Doing Youtube": information creating in the context of serious beauty and lifestyle Youtube. (Doctoral dissertation). University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, U.S.

- Trace, C. B. (2007). Information creation and the notion of membership. Journal of Documentation, 63(1), 142–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410710723920

- Wakkary, R. & Maestri, L. (2007). The resourcefulness of everyday design. Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGCHI Conference on Creativity & Cognition, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1145/1254960.1254984

- Whittaker, S. (2011). Personal information management: from information consumption to curation. Annual review of information science and technology, 45(1), 1–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2011.1440450108

- Whittaker, S., Terveen, L. & Nardi, B. A. (2000). Let's stop pushing the envelope and start addressing it: a reference task agenda for HCI. Human Computer Interaction, 15, 75–106. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327051HCI1523_2