Membership of the editorial boards of journals published by the predatory publisher OMICS: willing and unwilling participation

Michael Downes

Introduction. OMICS is the largest and most successful predatory publisher, with numerous subsidiaries. In 2019 it was convicted of unethical publishing practices.

Method. A numerical tally of OMICS's editorial listings was compiled across 131 nations. Names and affiliations were recorded for seven nations. A sample was surveyed to estimate the proportions of those aware and unaware of their listing, and of OMICS’s conviction.

Analysis. Excel enabled compilation, absolute and proportional tallies and random selection.

Results. OMICS has twenty subsidiaries and 26,772 editor (and editorial board) listings, 11,361 from just seven nations. Proportional to population, Greeks were most frequently represented on OMICS's editorial boards, followed by Americans, Singaporeans and Italians. In absolute terms, Americans were the most numerous. The survey found that more than half of the respondents were either unaware of their listing or were unwilling to be listed, and 26% were unaware of OMICS’s conviction.

Conclusion. OMICS's editorial boards do not function as they do for respectable publishers, hence the information published in OMICS journals is unreliable. Academic alliances with OMICS are potentially damaging to academic careers and institutional reputations. Universities should develop policies dealing with predatory publishers in general and OMICS in particular.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper912

Introduction

University of Colorado Librarian Jeffrey Beall, now retired, brought the concept of ‘predatory publishers’ to the attention of the academic community via blog posts. on his Website scholarlyopenaccess (closed down in 2017) and in a series of articles (Beall, 2012. 2013, 2015, 2016. 2017; Bresgov, 2019a, 2019b) which proved hugely influential and controversial (Basken, 2017; Berger and Cirasella, 2015; Brown, 2015; Crawford, 2014a, 2014b, 2016; Downes, 2020a; Pleffer and Shrubb, 2017; Yeates, 2017). Beall’s famous list of potential, possible and probable predatory publishers ranged from naïve amateurs with wholly uninformed and usually unsuccessful attempts to exploit the open access scholarly publishing market to educated, sophisticated enterprises out to do the same. Among the former we might name Antarctic Journals, Best Journals, Central Research Insight and Developing Country Think Tank Institute, all long since gone, while also noting that several others have marked their lack of success and ultimate demise by leaving their Websites with destructive malware, presumably out of spite. For that reason, it is wise to be cautious when using any archived versions of Beall’s original list. Among the more convincing examples of thriving, well-established bogus publishers are hundreds whose counterfeit practices have been critiqued and publicised by many commentators (Cobey 2017; Cress and Sarwer, 2019; Petrisor, 2016) and documented in a new list that preserves and updates the one left to us by Beall, effectively continuing where he left off (Downes, 2021a).

Predatory publishers are distinguished by their lip service, if any service, to the ethical and professional norms of scholarly publishing, especially peer review. They vary in their degrees of culpability but in general the operations of these pseudo-publishers are driven not by the desire to promote or disseminate credible information but primarily if not solely with the aim of making money, and for this reason can be described as deceptive, unscrupulous, counterfeit, scam, racketeer or bogus. The worst of these junk market enterprises pose a danger to society, not so much because of their unscholarly motives per se, but because in doing so they publish work without the necessary or often any professional scrutiny, thereby eroding public trust in scholarship in general and science in particular at a time when this trust is coming under uncommon and irrational assault from many directions.

OMICS, based in Hyderabad, India, is generally recognized by all measures as being the largest and most successful of these so-called predatory open access publishers, as well as being one of the two most prolific organisers of predatory conferences (the World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology being the other). It has the unenviable distinction of being the only open access publisher convicted of predatory deceptive practices in a western (American) court (U.S. Federal Trade Commission, 2019). This occurred in April 2019, and you might suppose that academics, especially Americans, serving on the editorial boards of OMICS's journals would have since taken steps to disengage themselves, and that universities and research agencies mindful of their reputations would have urged or required them to do so and drafted policies designed to prevent future alliances with OMICS. If the accounts and reports of numerous contributors over the past decade had received the attention they deserved and had awakened more disquiet among individuals and institutions proud of their standards of scholarly integrity, these reforms might have occurred on a scale befitting the seriousness of the problem.

Having investigated the OMICS Publishing Group and other illicit publishers since late 2017 (Downes, 2020a, 2020b), I am well aware that there has been very little academic disengagement and even less drafting of institutional policy. On the contrary, there has been no shortage of deniers and other voices that have played down the actual and increasing harm being done to the academy (Eve and Priego, 2017; Faulkes, 2015; Oberhaus 2018), or shifted the narrative from the offenders large and small to a vilification of Jeffrey Beall (Crawford, 2014a, 2014b, 2016; Yeates, 2017). Perhaps the new information reported here might persuade some scholars and universities to focus less on Jeffrey Beall and more on the high-level predatory offenders.

Of OMICS's various illicit practices cited by the US Federal Trade Commission and documented by others (Deprez and Chen, 2017; Gillis, 2017; Puzic, 2016; Readfearn, 2018), arguably the worst is its habit of helping itself to the identities of scholars working in American, British and other western universities and research institutions, by claiming them for editorial boards without mentioning this to the people concerned. Nor is OMICS the only offender in this regard. Hundreds of other disreputable scholarly publishers do likewise (Downes, 2021a). The most likely and most unsurprising reason for this goes to one of the many deplorable features of the present world order: although global north academics are not immune from publishing in junk journals (Moher et al., 2017; Oberhaus, 2018; Pyne, 2017; Staudenmaier, 2018), it is authors from the global south who make up by far the majority of clients (Matumba et al., 2019; Moher et al., 2017; Petrisor, 2016; Shen and Björk, 2015; Tella, 2020; Xia et al., 2015). For financial reasons, among others, they are largely excluded from the most prestigious platforms and are prone to send their work and their money to substandard publishers whose editorial boards are top-heavy with arguably prestigious names and certainly prestigious (hence compelling) affiliations; and whose benefits, especially low open access fees, swift peer review and rapid publication, seem too good to be true, and in most cases are, at least with regard to the promise of serious and professional peer review and hence to the reliability of the information contained in their articles.

Without limiting the aims of this article, they are broadly threefold: to collate the constituents of the OMICS Publishing Group, to record the numbers and nationalities of academics currently serving on the editorial boards of its journals, and to estimate how many of those are doing so willingly, and how many unwillingly (and unwittingly). The results give grounds for recommendations on what might be done to rectify the situation and who might best be doing it.

Method

Using contact information and other evidence from their Websites, twenty publishers were identified as OMICS's subsidiaries, imprints or shopfronts (Table 1). This included noting whether their stated addresses were physical or virtual, i.e., whether their true locations were being revealed or concealed.

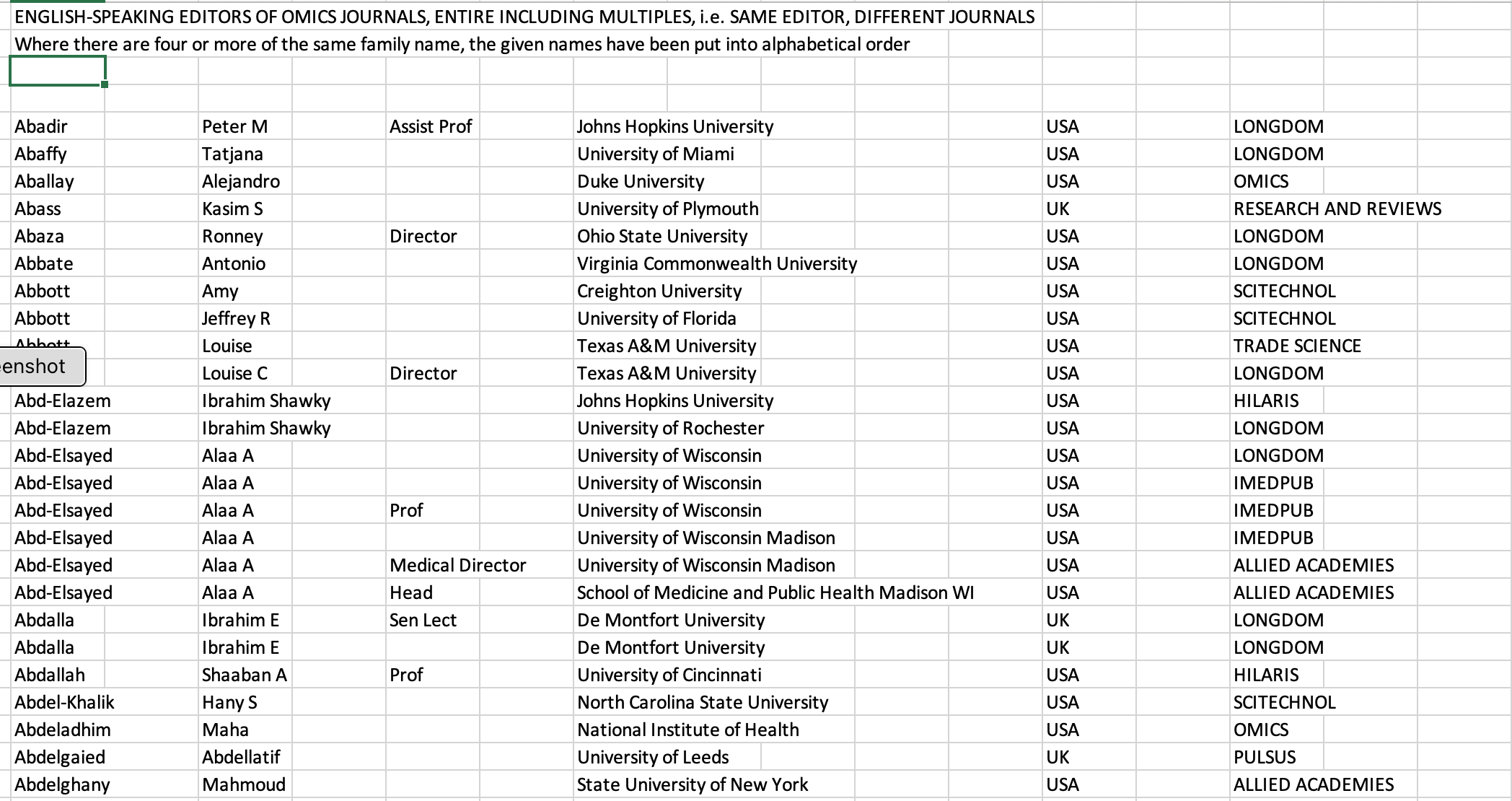

A numerical tally of OMICS's editorial board member listings by nationality was carried out between April and November 2020. There were 26,772 in total (see dataset at Downes, 2021b) from 131 nations, of which 11,361 comprised academics from seven English-speaking nations (see dataset at Downes, 2021c). By English-speaking academics, I mean those currently working in Australia, Canada, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. This choice of seven nations was made to limit the workload and for reasons of practicality of communication via a survey. Names and affiliations were recorded for these seven nations; nationalities only for the others. Many of the English-speaking names were repeated (same academic, different journal). Adjusting for this, the number of individual English-speaking names was 9182 (see dataset at Downes, 2021d); the same proportionality does not necessarily follow for the dataset as a whole. For ease of expression and to avoid unnecessary complications, no distinction is made in this article between Editors in Chief and editorial board members. Unless expressly stated, all are editorial board members, or simply editors.

It is highly likely that the dataset contains errors. Identical names (and sometimes identical affiliations as well) can be wrongly supposed to denote the same person; nationalities can be obscure, difficult to confirm and sometimes just plain wrong; and there are undoubtedly my own errors of transcription and interpretation. The sample sizes, however, all but guarantee that these will have negligible or no effect on the results.

Once the list was finalised, a survey was carried out. The names were numbered and a pseudo-random number generator was used to select 1,396 of them, i.e., a 15% sample. There were 636 who could not be contacted for a whole host of reasons, leaving just 760 successfully sent emails. From these, 129 responses were obtained. This low response rate was fully understandable but nonetheless disappointing, because it limited the net survey sample size. No unwarranted multiples were recorded, i.e., those who did not know they were editors were not counted among those who made no editorial contributions, because it could not be otherwise.

The survey email was never intended as a formal instrument, hence it did not consist of a set of questions. Instead, it was simply conversational, comprising an alert, an informal question, and an invitation to comment:

Dear [Dr / Prof]

I am studying editors of OMICS journals and I find you listed on the editorial board(s) of [journal name(s)]. OMICS was successfully prosecuted by the US Federal Trade Commission in 2019 for deceptive dealing. Has this affected the way you see your present and future service on [this OMICS journal / these OMICS journals]? Further comments are welcome. By replying, you are assisting my research and for that I am most grateful.

Thanks for your time, and wishing you well during the present health crisis.

Mike Downes

Independent Researcher

Ex James Cook University, Australia and Aarhus University, Denmark

The alert concerning the conviction of OMICS for deceptive publishing practices was included for two reasons. One, to ensure transparency in the context of the enquiry, and two, to garner some indication of how widely known, or otherwise, that federal prosecution was.

Results

The first OMICS journal was launched in 2008 and after a history of invention, fragmentation, acquisition and disbursement, the group now comprises twenty-one semi-autonomous entities, including Allied Academies, Hilaris, Insight Medical Publishing, Longdom, Open Access Journals, Pulsus, Research and Reviews, Scholars Research Library, Scitechnol, Trade Science, and OMICS International itself (Table 1). An earlier list is provided by Readfearn (2018). Also allied with or hijacked by OMICS in a way at present unclear are Nadia and Science and Engineering Research Support Society (SERSC). Nadia articles carry the footnote ‘Copyright 2017 SERSC Australia, and SERSC (before going defunct along with all nine of its journals) had the URL www.omicsonline, besides announcing ‘copyright Omics International.’ The very recent and illuminating history of Nadia, the legitimate Korean SERSC and the hijacking SERSC appears in a conversation arising from a question asked by Stephen Mason (2020).

| Name | Number of journals |

|---|---|

| Allied Academies | 120 |

| Allied Business Academies | 14 |

| Andrew John Publishing | 13 |

| Ashdin Publishing | 3 |

| Aston Journals | 4 |

| Australasian Medical Journal | 1 |

| Consortium | 0 |

| E Science Central | 0 |

| GSB Life Sciences | 0 |

| Hilaris Publisher | 125 |

| Insight Medical Publishing | 240 |

| IOKSP* | 0 |

| Longdom | 193 |

| OMICS International | 102 |

| Open Access Journals | 10 |

| Pelagia Research Library | 0 |

| Pulsus | 74 |

| Research and Reviews | 35 |

| Scholars Research Library | 11 |

| Scitechnol | 91 |

| Trade Science | 24 |

| TOTAL | 1060 |

| *IOKSP: International Online Knowledge Service Provider. | |

Pulsus and Andrew John Publishing were purchased in 2016 in a transaction that apparently resulted in OMICS breaking a promise to keep these new assets free of predatory violations of ethical publishing practice (Brown, 2016). The number of journals stated for Allied Academies has changed markedly since the time of compilation dropping from seventy-two titles in January 2021 to thirty in February 2021. This is not unusual with OMICS and its subsidiaries, for which transfers en bloc and/or inconsistency in form and content of journal listings is normal practice. I have therefore left the entry as it was when compiled. In December 2018, Hilaris had only four journals, two of which were inaccessible. By January 2020 there were seventy-six titles. Many if not all came direct from the motherload at OMICS International, and the same story applied eight months later, with the tally running at 125. A similar account could be given for other subsidiaries, especially Longdom. As a result, OMICS International itself is no longer the main publisher of its journals, at least not directly.

One physical address (40 Bloomsbury Way, Lower Ground Floor, London) is given by the British Government Companies House for six members of the OMICS Publishing Group. As discussed below, none are presently registered there and few, if any, were ever there physically.

Table 2 provides comparative scores, indexed to population, of OMICS editorial board listings for the thirty-two nations with the highest per capita index values. The values used in the summary for nationalities are for listings rather than individuals because individual names were collated for only seven of the 131 nations encountered during the study. To ensure robust reliability of the comparisons, only nations with 100 or more listings were used. The overall index for all 131 nations was 3.6. For the selected countries in Table 2 it was 4.7. For the seven English-speaking nations it was 23.9. Proportional to population, Greeks are by far the leading contributors of editors to OMICS journals, followed by the USA, Singapore and Italy. In absolute terms, Americans (9360) are by far the most numerous, ahead of India (2390), China (1637) and Italy (1387).

| Country | Listings | Population (millions) | Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 452 | 10 | 45.2 |

| USA | 9360 | 331 | 28.3 |

| Singapore | 148 | 6 | 24.7 |

| Italy | 1387 | 60 | 23.1 |

| Canada | 623 | 38 | 16.4 |

| Portugal | 163 | 10 | 16.3 |

| Israel | 146 | 9 | 16.2 |

| Australia | 395 | 25 | 15.8 |

| United Arab Emirates | 155 | 10 | 15.5 |

| Taiwan | 340 | 24 | 14.2 |

| UK | 862 | 68 | 12.7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 370 | 35 | 10.6 |

| Sweden | 106 | 10 | 10.6 |

| Spain | 474 | 47 | 10.1 |

| Turkey | 763 | 84 | 9.1 |

| Romania | 159 | 19 | 8.4 |

| Egypt | 664 | 102 | 6.5 |

| Poland | 229 | 38 | 6.0 |

| Iran | 486 | 84 | 5.8 |

| Japan | 697 | 126 | 5.5 |

| Germany | 382 | 84 | 4.5 |

| France | 269 | 65 | 4.1 |

| India | 2390 | 1380 | 1.7 |

| China | 1637 | 1447 | 1.1 |

| Russia | 140 | 146 | 1.0 |

| Nigeria | 171 | 206 | 0.8 |

| Pakistan | 110 | 221 | 0.5 |

The essential content of the 129 responses to the survey from English-speaking editors is summarized in Table 3. The figures can only suggest minima rather than predict actual proportions because, for instance, respondents unaware of the prosecution of OMICS may not mention that fact. Only a negligible number of respondents gave a positive account of their experiences as an OMICS editor, while 26% were unwittingly involved and 29% had their resignation requests ignored, typically for years. An additional 37% advised that they had provided little or no input to the editorial process, and some partial insight into the reason is provided by a survey respondent who reported as follows:

I agreed to serve as Editor-In-Chief... I was surprised to learn that the editor-in-chief plays no role in the processing of manuscripts ... I had zero correspondence regarding any submitted, reviewed, or published manuscripts ... the "journal administration" handled all of that and would not allow me to participate.

| Comment | Number of instances |

|---|---|

| I did not know that I was listed on the editorial board | 33 |

| I cannot get my name removed | 38 |

| I am listed but I have never done any editing for them | 33 |

| I did a little for them a long time ago | 15 |

| I thought these people were genuine. I know better now. | 19 |

| I did not know that OMICS had been prosecuted | 34 |

| After the conviction I stopped or will stop working with OMICS | 13 |

| The OMICS journal I serve is respectable and professional | 3 |

| It benefits me to continue serving despite OMICS’ prosecution | 1 |

| Other or no informative content | 8 |

| Total number of replies | 129 |

Discussion

“Deceptive practices” were singled out by the US Federal Trade Commission in its legal report on OMICS. Six subsidiaries or members of the OMICS Publishing Group (Allied Academies, Andrew John, the Australasian Medical Journal, Open Access Journals, Pulsus and Scitechnol) use or have used the same London address. None will be found there currently (although it is possible there is a mail forwarding service) and the likelihood of any of them ever being there physically, as opposed to being temporarily registered there in the records of the British Government Companies House, is marginal. On the contrary, the existing records of the same agency seem to rule out some of them from ever being there in any capacity: Allied Academies deregistered from that address in February 2018 and went to 47 Churchfield Road, London W3 6AY, leaving in its registered wake official notes such as ‘dormant company’ and ‘strike-off action’. In November of the same year, it shifted again, to Bellegrove Road, Welling, Kent DA 16 3QR, a suburban dwelling it apparently shared with EHOAD Hair Signature, Octopus Food Art Fiction and sixty-one other companies (as at August 2020). I can only conclude that an address in a prestigious western capital is being used, in some cases without any basis whatsoever, to lend spurious international standing to an otherwise unremarkable organization whose only true controlling address is in Hyderabad, India. A comparable story could be told concerning OMICS’s publishing outlets. Some are mere shopfronts: the eighteen titles of GSB (Gedela Srinu Babu?) Life Sciences all redirecting to other OMICS subsidiaries; others were embroiled in controversy at the time of their acquisition (Brown, 2016; Puzic, 2016).

Another of the many egregious flaws in the ethical and professional standing of OMICS and its subsidiaries and imprints is the use of the notorious fake editor Alireza Heidari (Grover, 2017; Lowe, 2018). Heidari serves on the boards of 624 junk journals belonging to seventy-seven predatory publishers and eighty-five standalone journals, with these numbers constantly changing as old scammers disappear and new hopefuls arise weekly, almost routinely using Heidari and other stock characters to fill out their editorial boards. His own pseudo-biography (Heidari, n.d) is used over and again by many of his academic hosts, and just one example of his 474-and-counting preposterous articles shall suffice for any reader to agree with Derek Lowe (2018, para. 1) that, 'No "journal" that lets an Alireza Heidari on its "editorial board" can possibly be any good whatsoever.'

Example of one of Heidari’s papers:

Heidari, A. (2018). X–Ray Diffraction (XRD), Powder x–ray diffraction (PXRD) and energy–dispersive x–ray diffraction (EDXRD) comparative study on malignant and benign human cancer cells and tissues under synchrotron radiation. Journal of Oncology Research, 2(1), 1-14. https://gudapuris.com/articles/10.31829-2637-6148.jor2018-2(1)-e102.pdf

And OMICS? Heidari is on ninety-seven OMICS journal editorial boards covering waste management. electrochemistry, livestock production, immunology, surgery, pharmacy, pulmonology, cancer, heavy metals, nursing, mathematics. psychiatry, nanoscience and a host of other disciplines, and he is the editor-in-chief of three of them.

Concerning real people whose names appear on the editorial boards of journals marketed by OMICS's outlets, and bearing in mind the cautionary note made in the Method above, a simple extrapolation tells us that if the proportion of names to listings for all OMICS editors is consistent with that found for the English-speaking cohort (about 80%), then approximately 22,000 academics worldwide currently serve on editorial boards of the subsidiaries and imprints of OMICS International, excluding of course any OMICS imprints unknown to me. It is also plain that anyone browsing OMICS's international journals will find on their editorial boards more Americans by far than academics of any other nationality, indeed, more than twice the number of Indian and Chinese academics combined.

The survey data do not, however, unequivocally support the conclusion that a quarter of all participants may have been included without consultation. For one thing, it is human nature to be more ready to voice a grievance than to report that nothing is untoward. Hence it is likely, at least on that basis, that Table 3 overstates the proportion of editors whose names and affiliations have been used without permission. Also, while it seems sound to make cautious estimates for the English-speaking cohort, this cannot be assumed to apply to the other nationalities if OMICS uses western identities in a bid to make its journals look more prestigious to budding authors from developing or semi-developed nations. It is not hard to explain why OMICS would want ten to twenty times more Australian, British, Canadian and especially American names there, than Chinese or Indian ones, proportional to population. It is more of a challenge to explain why Italians and Singaporeans are almost as numerous as Americans; why there are ten times as many Romanians as Nigerians; why there are nearly thirty times as many Taiwanese as Pakistanis. Moreover, why so few Indians, given that the proprietor is an Indian publisher? Perhaps the excesses of some nationalities result from overzealous recruiting by OMICS managers of the nationality concerned.

The most singular anomaly, however, is clearly Greece, which has twice as many OMICS editors per head of population as the USA. Do Greeks seek OMICS out, or does OMICS preferentially seek out Greeks? Is there something in the Greek national academic culture that permits scholars to be far more readily recruited to the service of predatory publishers than scholars from other countries? In this context, it is necessary to point out the case of Cyprus, which was not included in Table 2 because it offered only twenty-nine editors. But with a population of just one million, it also had (just) a higher number of editors per head of population than the USA. This would put Greece and Cyprus together at the top of the list, and the reasons for this are open to speculation.

We can concur, from what is generally known about OMICS (Brown, 2015; Deprez and Chen, 2017; Gillis, 2017; Masic, 2017; Puzic, 2016), and from the results presented above, that OMICS's editorial boards do not function as they do for respectable publishers. Scholars from the global north seem to be for the most part there to entice, not to do editorial work. Their affiliations are similarly there to impress, regardless of currency. It follows that if an academic on the board has the misfortune to die, as a number have, that does not affect or curtail that person's role as an editor. They can fulfil their function just as well dead as alive.

With regard to those respondents whose recall was sparked by my correspondence, ten or more years was by no means unusual as a measure of the oft-repeated phrase, ‘a long time ago’. One professor had been sending reminders of his resignation every few months for eight years, without effect. Sending is not always the same thing as arriving, however, and arriving is not always the same thing as finding the correct portal, namely the inbox of someone who cares. But arriving is at least better than not arriving, which is the fate of many attempts to contact OMICS and its subsidiaries, as a number of respondents found.

Counter to the above reasoning, however, the number and hence the likely rough proportion of respondents complaining that their names are being used without their consent might well understate rather than overstate the true state of affairs. The reason is that those recipients who glanced cursorily at the content of my email before deleting are more likely to be the ones who saw nothing in it of relevance to them, i.e., the name of the journal meant nothing to them because they did not know that they were listed on its editorial board.

It seems fair to OMICS to concede that some cases of apparently stolen academic identities could well be ones of the kind cited by Poynder (2011, p. 23): people having genuinely forgotten that they agreed to join the board and as a result believing that they are being named without their consent. But nobody at OMICS is exonerated on that account. If editors forget that they had agreed to serve many years ago and had never heard anything that might have reminded them, that confirms the face-value findings of the survey, that the large majority of editorial board members, at least the global north ones, are apparently there in name only. There is precious little hard evidence from the survey that anyone at OMICS is doing much (if anything at all) in the way of guiding professional peer review. One of the very few respondents who spoke positively about his experience with OMICS was on two editorial boards and advised me that he had a normal and professional engagement with one of them. As for the other, he was ‘not familiar’ with that one, a fact that apparently gave him no misgivings about his overall experience with OMICS.

That 34 respondents were unaware of OMICS’s 2019 conviction is arguably more concerning than the number whose identity has been thieved. The latter is par for the course in the junk open access pay-to-publish market. But the former, the one in four (at least) who have not yet been updated on the biggest event in the fight against open access predatory publishing should be discomforting to those institutional officials responsible for maintaining awareness of the bogus publishing industry and its anti-scholarly practices.

Some of OMICS’s numerous questionable practices can be put down to incompetence. The major systemic ones cannot. That is why no scholars of integrity should be enabling this publisher by serving on its editorial boards. Any academic who is content to serve in an editorial (or any other) role with OMICS must share its reputation, and unfortunately this applies also to those unaware, too busy to bother or without redress. Any university that passively allows them to continue doing so either does not take research integrity seriously, remains inexplicably unaware of the detrimental intrusion of OMICS into the daily life of its academic community, or believes that education is a sufficient response to the problem of predatory publishers, perhaps trusting that any more serious opinions will fly under the radar.

There remains the concerning matter of academics who openly or otherwise collaborate extensively with OMICS (and other predatory publishers) for benefit. Some list their alliances as authors or editors or both on their institutional bios and their CVs, counting these accomplishments to their credit in ways that could impress appointment and promotion committees (Beall, 2017). With others it seems to me more like an addiction than a strategy, and the number of addicts is large. Among the more colourful cases is that of a senior American academic who was embarrassed to admit that he served on 321 predatory editorial boards including thirty-nine with OMICS, and in response to the disapproval of his superiors, undertook to explain how it was done and even to assist, in a spirit of repentance, in educating junior staff on the subject of disreputable open access publishers (confidential communication to the author). But at least he is alive and actually exists, unlike Alireza Heidari whose prominence is remarkable for a fictitious character, and whose appearance is a sure guide to a publisher’s illicit nature.

What can and should be done, and by whom

After the extent of predatory publishing’s infiltration into Australian academia was provisionally detailed (Downes, 2020b), at least three Australian universities moved to strengthen their policies. Most, however, chose not to engage in that way with racketeer publishers and especially not with their academic staff, preferring to keep potential disputes to a minimum by persisting with what has been done for more than a decade: promoting awareness seminars and other forms of professional development. In other words, to use currently familiar terms, they went soft and late instead of going hard and early. Meanwhile research agencies and universities in other global north countries have not to my knowledge been any more active than those in Australia, probably even less so.

It is therefore disappointing to see in the academic listings (see dataset at Downes, 2021e) evidence of numerous scholars currently in American and other nations’ universities whose engagement with the editorial boards of OMICS journals still far exceeds the ethical expectations of faculty, given that even one appearance should be a professional embarrassment. In addition, OMICS is just one among many large-scale predatory publishers that host willing and unwilling editors. Each academic is responsible for the integrity of their own scholarly practice, and it is not enough, even for those who had no say in the theft of their names, affiliations and reputations, to shrug and plead helplessness, or simply to ignore the matter. If they know that their names are being used without their permission (and many hundreds do, either because I have told them or because they have found out via other channels), they should state explicitly on their institutional bios that they deny willing compliance with publishers other than the ones they list rightly to their credit. That is a reasonable expectation. They should also be keeping records of correspondence aimed at getting their names removed from the Websites of unethical publishers, with a view to making those records available to the Competition and Markets Authority (United Kingdom), the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and other corresponding counterparts of America’s Federal Trade Commission in countries that value the integrity of scholarship. Action at the federal level is more likely to be taken if thousands of academics are recording their complaints and making them known.

But equally if not more responsible are their institutions, primarily the universities. They have the means to draft and mandate effective policies. They have the responsibility to demonstrate leadership by doing so. And they literally owe it to society if they are in whole or part publicly funded. Deputy Vice Chancellors (Research) and Research Integrity Officers should be developing and implementing policies that condemn and proscribe staff alliances with anti-scholarly racketeers and mandate that any such alliances cannot be used to advance academic careers. Moreover, given clear evidence of career advancement having been achieved on the back of alliances (especially publications} with unscholarly open access racketeers, a review of past promotions should be undertaken. So far there has been a chronic and timid reluctance (i.e., failure) to take either step. Either by choice or default those responsible have decided (not least, it seems, from fear of litigation by the supposedly maligned parties) not to heed the potent advice of informed investigators and the ever-growing body of damning evidence. Apparently satisfied with the feeblest of provenly ineffective responses, they let the destructive and embarrassing circus of unscholarly, predatory publishers in general, and OMICS in particular, thrive and multiply (McCrostie, 2018; McQuarrie et al., 2020).

I have presented new and compelling grounds for universities to take meaningful action against OMICS, action other than to circulate yet another memo cautioning researchers about the existence of bogus open access publishers. Such memos have been flying around for more than a decade with little and arguably no progress to show for them. It is time for the academy to take a long-overdue stand against OMICS and other pseudo-publishers who may not be as big but are as bad or worse in their trashing of ethical and scholarly norms. This, in essence, is what a long list of exasperated scholars have been saying and prescribing for years (Cobey, 2017; Cress and Sarwer, 2019; Eriksson and Helgesson, 2017, 2018; Wehrmeijer, 2014). OMICS is making a mockery of scholarship in general and science, especially medical science, in particular (Beall, 2012; Deprez and Chen, 2017; Puzic, 2016). The unreliability of the information we get from OMICS and its imitators threatens not only the public’s trust in academia, already assailed on other fronts, but the promise of free and open access to the results of research.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the scholars who responded to my survey and especially those who provided, at unexpected length, insights into OMICS’ editorial practices.

About the author

Mike Downes’s research fields are in arachnology and entomology. He obtained his PhD from James Cook University, Australia, before doing postdoctoral work at Aarhus University, Denmark. Now long since retired from academia and his research interests in arachnology, he has been studying the black weaver ants of North Queensland while tutoring mathematics. Since investigating an open access spammer in 2017 he has been preoccupied (obsessed?) with fraudulent pseudo-publishers. He maintains a Website called Scholarly Outlaws. He can be contacted at mikedownes@bigpond.com

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Basken, P. (2017, September 22). Why Beall’s blacklist of predatory journals died. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20170920150122306 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ltETHu)

- Beall, J. (2012, August 1). Predatory publishing: overzealous open-access advocates are creating an exploitative environment, threatening the credibility of scholarly publishing. The Scientist. https://www.the-scientist.com/critic-at-large/predatory-publishing-40671 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/30dOz0y)

- Beall, J. (2013). The open-access movement Is not really about open access. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. 11(2), 589-597. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v11i2.525 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3BpSpkR)

- Beall, J. (2015, January 1). Criteria for determining predatory open-access publishers. (3rd ed.) https://beallslist.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/criteria-2015.pdf (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3Asj7bm)

- Beall, J. (2016). Ban predators from the scientific record. Nature, 534 (326). https://doi.org/10.1038/534326a (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3lumZEp)

- Beall, J. (2017). What I learned from predatory publishers. Biochemia Medica (Zagreb), 27(2), 273-278. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2017.029 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3iR5zjz)

- Berger, M., & Cirasella, J. (2015). Beyond Beall’s list: better understanding predatory publishers. College & Research Libraries News, 76(3), 132–135. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.76.3.9277.(Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ltOUUR)

- Brezgov, S. (2019a, May 27). Beall’s list: potential, possible or probable predatory scholarly open-access publishers. Scholarly Open Access. (Originally posted on January 12, 2017). https://scholarlyoa.com/publishers (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3DsbfZ9)

- Brezgov, S. (2019b, July 16). The serials crisis is over. Scholarly Open Access. (Originally posted on May 7, 2013). https://scholarlyoa.com/the-serials-crisis-is-over/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3oPMYIk)

- Brown, C. (2016). Alleged predatory publisher buys medical journals. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188(16), E398. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5338 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ltnzSL)

- Brown, M.J.I. (2015, August 3). Vanity and predatory academic publishers are corrupting the pursuit of knowledge. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/vanity-and-predatory-academic-publishers-are-corrupting-the-pursuit-of-knowledge-45490 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2WXzxKW)

- Cobey, K. (2017). Illegitimate journals scam even senior scientists. Nature, 549(7670). https://doi.org/10.1038/549007a (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3lvvsaA)

- Crawford, W. (2014a). Ethics and access 1: the sad case of Jeffrey Beall. Cites and Insights, 14(4), 1-14. https://citesandinsights.info/civ14i4.pdf (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3v1MOPu)

- Crawford, W. (2014b). Journals, "journals" and wannabes: investigating the list. Cites & Insights, 14(7), 1-45. http://citesandinsights.info/civ14i7on.pdf (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2Yz5Xwl)

- Crawford, W. (2016, January 29). "Trust me": the other problem with 87% of Beall’s lists. Walt at Random. https://walt.lishost.org/2016/01/trust-me-the-other-problem-with-87-of-bealls-lists/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3lt6p7I)

- Cress, P. E., & Sarwer, D. B. (2019). Predatory journals: an ethical crisis in publishing. Aesthetic Surgery Journal Open Forum, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/asjof/ojz001 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3AttPhQ)

- Deprez, E. E., & Chen, C. (2017, August 29). Medical journals have a fake news problem. Bloomberg Businessweek. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-08-29/medical-journals-have-a-fake-news-problem (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3oPX8J2)

- Downes, M. (2020a). Why we should have listened to Jeffrey Beall from the start. Learned Publishing, 33(4), 442-448. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1316

- Downes, M. (2020b). Thousands of Australian academics on the editorial boards of journals run by predatory publishers. Learned Publishing, 32(3), 287-295. https://doi.org/10.1002/leap.1297

- Downes, M. (2021a, March 11). Beall’s list is back. Scholarly Outlaws. https://scholarlyoutlaws.com/index.php/2020/03/11/unlist-yourself/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3oXAoam)

- Downes, M. (2021b, July 15). OMICS editors by nationality [Data set]. Scholarly Outlaws. https://scholarlyoutlaws.com/index.php/2021/07/15/omics-editors-by-nationality/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3AQPm4N)

- Downes, M. (2021c, July 15). English speaking editors of OMICS journals. [Data set]. Scholarly Outlaws. https://scholarlyoutlaws.com/index.php/2021/07/15/english-speaking-editors-of-omics-journals/

- Downes, M. (2021d, July 15). English-speaking editors of OMICS journals, names only. [Data set]. Scholarly Outlaws. https://scholarlyoutlaws.com/index.php/2021/07/15/english-speaking-editors-of-omics-journals-names-only/

- Downes, M. (2021e, July 15). English-speaking editors of OMICS journals, listings. [Data set]. Scholarly Outlaws. https://scholarlyoutlaws.com/index.php/2021/07/15/english-speaking-editors-of-omics-journals-listings/

- Eriksson, S., & Helgesson, G. (2017). The false academy: predatory publishing in science and bioethics. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 20, 163-170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11019-016-9740-3 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3iRfUvM)

- Eriksson, S., & Helgesson, G. (2018, May 2). Where to publish and not to publish in bioethics: the 2018 list. The Ethics Blog. https://ethicsblog.crb.uu.se/2018/05/02/where-to-publish-and-not-to-publish-in-bioethics-the-2018-list/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3oQjHh0)

- Eve, M.P., & Priego, E. (2017). Who is actually harmed by predatory publishers? tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 15(2), 755-770 https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v15i2.867 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3AJJf1D)

- Faulkes, Z. (2015, April 6). How much harm is done by predatory journals? NeuroDojo. http://www.neurodojo.blogspot.com/2015/04/how-much-harm-is-done-by-predatory.html (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3BuwatX)

- Gillis, A. (2017, January 12). Beware! Academics are getting reeled in by scam journals. UA/AU: University Affairs, Affaires Universitaires. https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/beware-academics-getting-reeled-scam-journals/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3aow4rZ)

- Grover, W. H. (2017, December 10). "The University of Alberta, Southern California". Grover Lab. https://groverlab.org/hnbfpr/2017-12-10-csu.html (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3arE8bC)

- Heidari, A. (n.d.). Prof. Dr. Alireza Heidari. http://calsu.us/index.php/member/prof-dr-alireza-heidari/ (Archived at Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3FBJ3Vy)

- Jalalian, M. (2015). Solutions for commandeered journals, debatable journals, and forged journals. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry, 6(3), 283-285. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237X.161852 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/30cjHxi)

- Lowe, D. (2018, February 21). Down the rabbit hole with Alireza Heidari. In the Pipeline. https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2018/02/21/down-the-rabbit-hole-with-alireza-heidari (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ButdK3)

- McCrostie, J. (2018). Predatory conferences: a case of academic cannibalism. International Higher Education, 93, 6-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2018.93.10370 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/30k0GJt)

- McQuarrie, F.A,E., Kondra, A.Z., & Lamertz, K. (2020). Do tenure and promotion policies discourage publications in predatory journals? Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 51(3), 165-181. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.51.3.01

- Masic, I. (2017). Predatory publishing: experience with Omics International. Medical Archives, 71(5), 304-307. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2017.71.304-307 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3BuBZI5)

- Mason, S. (2020, August 6). Does anyone know what has happened to the International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology (IJAST)? https://bit.ly/3p4FgsD. (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3lrw2pw)

- Matumba, L., Maulidi, F., Balehegn, M., Abay, F., Salanje, G., Dzimbiri, L., & Kaunda, E. (2019). Blacklisting or whitelisting? Deterring faculty in developing countries from publishing in substandard journals. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 50(2), 83-95. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.50.2.01

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Cobey, K.D., Lalu, M.M., Galipeau, J., Avey, M.T., Ahmadzai, N., Alabousi, M., Barbeau, P., Beck, A., Daniel, R., Frank, R., Ghannad, M., Hamel, C., Hersi, M., Hutton, B., Isupov, I., McGrath, T.A., McInnes, M.D.F., … & Ziai, H. (2017). Nature, 549, 23-25. https://doi.org/10.1038/549023a (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3v3dfnU)

- Oberhaus, D. (2018, August 14). Hundreds of researchers from Harvard, Yale and Stanford were published in fake academic journals. Vice. https://bit.ly/3nY7KVv. (Archived by Internet Archive at Archive at https://bit.ly/2WZlUei)

- Petrisor, A-I. (2016). Evolving strategies of the predatory journals. Malaysian Journal of Library and Information Science, 21(1), 1–17. https://mjlis.um.edu.my/index.php/MJLIS/article/view/1714/2436 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3kTeliD)

- Pleffer, A., & Shrubb, S. (2017, March 27). Not the Beall and end-all. Australasian Open Access Strategy Group. https://archive.oaaustralasia.org/webinar-series-2017/ (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3FBOiVe)

- Poynder, R. (2011, December 19). The OA interviews: OMICS Publishing Group’s Srinu Babu Gedela. https://richardpoynder.co.uk/OMICSa.pdf (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3iRpwqm)

- Puzic, S. (2016, September 28). Offshore firm accused of publishing junk science takes over Canadian journals. CTVNews. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/offshore-firm-accused-of-publishing-junk-science-takes-over-canadian-journals-1.3093472 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3Fxq12B)

- Pyne, D. (2017). The rewards of predatory publications at a small business school. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 48(3), 137-160 https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.48.3.137

- Readfearn, G. (2018, January 12). All those OMICS linked companies in one place. Graham Readfearn. https://www.readfearn.com/2018/01/all-those-omics-linked-companies-in-one-place/#more-2363 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3AuvPGo)

- Shen, C., & Björk, B-C. (2015). ‘Predatory’ open access: a longitudinal study of article volumes and market characteristics. BMC Medicine, 13(230). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0469-2 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3iRsQC6)

- Staudenmaier, R. (2018, July 19). Germany sees sharp rise in ‘fake science’ journal publications. DW News. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-sees-sharp-rise-in-fake-science-journal-publications-report/a-44742014 (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3FyECe6)

- Tella, A. (2020). Nigerian academics patronizing predatory journals: implications for scholarly communication. Journal of Scholarly Publishing, 51(3), 182-196. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.51.3.02

- U.S. Federal Trade Commission. (2019, April 3). Court rules in FTC's favour against predatory academic publisher OMICS Group, imposes $50.1 million judgment against defendants that made false claims and hid publishing fees. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2019/04/court-rules-ftcs-favor-against-predatory-academic-publisher-omics (Archived by Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3asmYuc)

- Wehrmeijer, M. (2014). Exposing the predators: methods to stop predatory journals. [Unpublished master thesis]. Leiden University. https://studenttheses.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/28943

- Xia, J., Harmon, J.L., Connolly, K.G., Donnelly, R.M., Anderson, M.R., & Howard, H.A. (2015). Who publishes in "predatory" journals? Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(7), 1406-1417. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23265

- Yeates, S. (2017). After Beall’s ‘List of predatory publishers’: problems with the list and paths forward. In Proceedings of RAILS: Research Applications, Information and Library Studies, 2016, School of Information Management, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, 6-8 December, 2016. Information Research, 22(4), paper rails1611. http://InformationR.net/ir/22-4/rails/rails1611.html

How to cite this paper

Appendices

Appendix 1:

For the full version, click on this link