Integrating models and integrated models: towards a unified model of information seeking behaviour

Naresh Kumar Agarwal

Introduction. There has been a proliferation of information seeking models and theories, each incorporating different viewpoints, concepts, and terminology. While there have been prior attempts at integration, they have all focused on different facets of information seeking behaviour.

Method / Analysis. In this paper, I integrate models and frameworks in information seeking behaviour. I considered three groups of models: those that emerged in the 1980s and the 1990s; those from the year 2000 onwards; and integrated models. I mapped the important elements in the chosen models to each other. The unified subset of these elements was then used to create the unified model.

Results. I arrive at tables comparing the common elements in different models, a unified model of information seeking behaviour, and examples of propositions derived from the model. The unified model was finally extended to include information behaviour, other than seeking and searching.

Conclusions. The unified model should contribute to theory development by drawing attention to the common features and functions of elements in various models. The process of mapping could help researchers synthesise models and create a meta-model, and also serve as a methodological move of taking the work of a theorist and mapping other models to it. The unified model will help system designers view user needs, context, and their information seeking behaviour as central to building context-aware systems.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper922

Introduction

For more than three decades, researchers in information science have been trying to understand the motivations, thoughts, feelings, and activities that are involved when people look for information, as well as the contexts that affect this behaviour. These efforts have led to a proliferation of information seeking models and theories, each incorporating different viewpoints, concepts, and terminology. These efforts to understand seeking from the user’s point of view are often placed under the umbrella of the user-centred paradigm, distinct from the system-centred view that looks at search and search engines from a system designer’s point of view. However, even within the user-centred paradigm, different models make different metatheoretical assumptions, leading to discordant approaches to information seeking research at a fundamental level.

A unified model would help bring together these divergent perspectives. Researchers in the past two decades have attempted to integrate models. However, they have all focused on different facets of information behaviour, and were thus limited in the scope of their output. We are still far from a unified understanding of the work done thus far. It is an open question whether a unity of models is possible. As Wagner and Berger (1985) state, “to fully describe and understand theory growth it is necessary to look…at the relations between theories, the theory-theory linkages” (p.17) (as opposed to only theory-data linkages). Wagner and Berger (1985) describe theory integration as consolidating many of the ideas found in individual theories “in a single formulation, usually suggesting interrelationships between those ideas.” (p.57). They argue that “theory integration often constitutes the 'major advance' that is the clearest evidence of progress since it both unifies and deepens our knowledge…although integration...is rather rare when it is successful its impact may be quite dramatic.” (p.59)

There could be questions such as: Why is integration necessary or desirable? Is the ultimate goal for information seeking to have one overarching model or is there value in diversity? There is certainly value in multiple models from various researchers that speak to different perspectives, metatheories, research traditions, times and places, etc. These help to expand the field. And yet, as the field gets model-diffuse, efforts towards integration and synthesis become important, to try to make sense of it all. To strike a balance, welcoming diversity in models, but also seeking unity in that diversity, are different but important endeavours.

In this effort towards unity in diversity and to reconcile different perspectives in information seeking behaviour, I seek to compare and contrast different models (see e.g., Kundu, 2017, which compares a few models), as well as prior integrated models, to present a unified model of information seeking behaviour. I use the term unified model to distinguish it from integrated model, as it includes the integration of prior individual models, as well as earlier integrated models that have been developed by researchers in the field (although the term unified model was also used by Liu (2017) when applying mathematical modelling to information behaviour). This wholistic synthesis, also including prior integrated models, is what makes this work different from prior integration efforts.

The specific research questions are the following:

- What are the key components of existing information seeking models and frameworks, and what functions do they serve within the information seeking process?

- How can these components be integrated into a core set of elements common to various research approaches in information seeking?

- How does this unified model compare to existing integrated models?

The unified model I present brings in important elements from several past information seeking models and draws on the work of leading researchers in the field. Here, the term element (also used in Agarwal, 2018) can be thought of as a component (used in an equivalent sense by Savolainen, 2017a), or a part of the whole (Wagner and Berger, 1985 called this theory integration). My goal is not just to integrate the models mechanically, but to look for common ground between them to bring about a cohesive understanding of the research to this point. At the same time, I recognise and respect the differences inherent in these various approaches to information seeking, in the spirit of Dervin’s (1992; Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012; Agarwal, 2012) sense-making approach. As Dervin and Huesca (2001/2003) write, her approach “focuses not on homogenizing difference but on putting difference into dialogue and thus, using it to assist human sense-making. Such a…theory…assumes that when difference is not treated dialogically, it appears both capricious and chaotic as if needing homogenization” (p.310). In navigating between polarities, Dervin terms her quest as her “schizophrenic search for the ‘in-between’” (Dervin and Foreman-Wernet with Lauterbach, 2003, p. x; Agarwal, 2012). In this paper, these differences in prior models provide an avenue for further elaboration of the unified model. As Wagner and Berger state, predictions of individual theories “are subsumed in the structure of the new [unified model], although it is unlikely that all will be subsumed.” (p.57)

I also provide examples of how propositions can be derived from the model that can help in the design of future empirical studies. Through this process of comparing, contrasting, mapping, and integrating, the hope is not so much of definitive unity among models, theories, and assumptions, as one of demonstrating a possible process of unifying, explained in the methodology section, and through the entirety of the paper; the goal is to help other researchers perform their own integrations. The unified model contributes to theory growth (Wagner and Berger, 1985) and development in the field. A unified understanding of user behaviour would also be useful to designers of information systems, in so far as emphasising the centrality of user needs, context, and their information behaviour in the user-system interaction process, and towards building context-aware systems. While what I have done is to look for “theory-theory linkages” (Wager and Berger, p.17), the model can be tested empirically through experiments and surveys, to look for “theory-data” linkages as well (Wagner and Berger, p.17). This should help bring about synthesis and convergence in research.

As I focus here on user-centred models of information seeking (an integration of what Wagner and Berger (1985) term, variant theories, where theories differ slightly from each other; and/or competing theories, where theories explain the same phenomenon in different ways), I view this paper as the beginning of a larger, perhaps unending, effort to synthesise work across the related fields of information science, information retrieval and human-computer interaction (what Wagner and Berger call proliferant theories, where ideas from one theory are applied in a different problem domain in a new theory).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. I review prior research and explain the methodology, where I examine the salient features of prior models. I then create the unified model based on this review. I compare and contrast the unified model to current models, to show the elements from each model that are included in the unified model. In the discussion and implications section, I indicate hypotheses or avenues of research inquiry that emanate from the unified model. This is followed by limitations, conclusions, and future work.

Literature Review

The goal of this review is to give an overview of the main streams of information seeking research. Since I review many studies, I adopt an enumerative approach for several studies and provide more detail where necessary.

Related Concepts

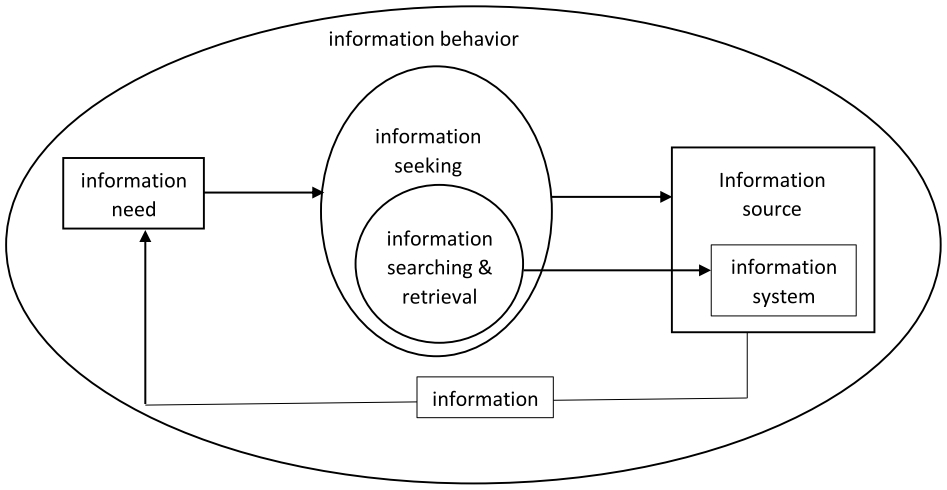

Several interrelated concepts have been studied in the interdisciplinary field of information seeking behaviour. Wilson (1999) came up with a nested model with three concentric circles, whereby information search behaviour is a part of information seeking behaviour, which, in turn, is a part of information behaviour. In Figure 1, I extend Wilson’s nested model (1999, p.263) to include need, source, system, and information.

Figure 1: Interrelated concepts in information seeking behaviour

Whilst there are multitudes of definitions for information (Case and Given, 2016), it can be seen as a phenomenon that is recognisable when we encounter it in its various forms or modes: as a message, proposition, or a socially-constructed human artefact (Case and Given, 2016; Savolainen, 2016a). Information need is defined as the recognition that our knowledge is inadequate to satisfy a goal we have. Taylor (1968) defined information need as falling under one of four types: visceral, conscious, formalised, and compromised, depending upon the degree of clarity and articulation of the need. Line (1974) distinguished need from other related terms such as want, demand, and requirement (also see Agarwal, 2015). Wilson (1981, p.8) suggests avoiding the term information need and instead referring to information-seeking towards the satisfaction of needs. Sonnenwald (1999) explicitly differentiates a perceived lack of knowledge from an information need, whereby a person might recognise a lack or gap, yet still not elevate it to the level of need. However, much information seeking literature does not make this distinction, with terms such as gap, uncertainty, anomalous state of knowledge, etc. used by researchers such as Dervin, Atkin, and Belkin respectively to explain information need. Cole (2012) views information need as an adaptive human mechanism, driving humans to seek out, recognise and then adapt to changes in their social and physical environments. Savolainen (2012) concludes that information need is formed and satisfied during a particular situation in action, when performing a task, or during dialogue. Savolainen (2017b) examines information need as a trigger and driver for information seeking, which we discuss below. Cole (2018, pp. 205-221) explores information need as it pertains to a person’s search for meaning. Ruthven (2019), following Taylor (1968), found that it is possible to differentiate levels of information need based on linguistic patterns. Information need both arises out of a context (whether work or everyday life) and helps shape context as well (Agarwal, 2018).

Information seeking is defined by Case and Given (2016) as a conscious effort to acquire information in response to a gap in our knowledge. The term has, however, been used to describe a variety of activities related to information acquisition; Savolainen (2016a) provides a thorough overview of the history and uses of the term information seeking. Following Bates (2002), he reviews the literature on four different modes of information seeking, characterised as either active or passive and either directed or undirected. Information searching is “a subset of information seeking, particularly concerned with the interactions between information user…and computer-based information systems” (Wilson, 1999, p.263). An information retrieval system leads the user to documents that help satisfy information need (Robertson, 1981) or solve problems (Belkin, 1984). Information behaviour is a more general field, subsuming seeking and searching, as well as other unintentional or intentional activities, such as avoiding information (Case and Given, 2016), or finding information serendipitously (Agarwal, 2015). It is concerned with information use and non-use, the processing of found information, and reasons for unsuccessful processing (Ford, 2015). Savolainen (2016a) attempts to clarify multiple competing concepts in information behaviour research.

Research and conceptual developments in information seeking

Models typically focus on more limited problems than do theories and sometimes may precede the development of formal theory (Case and Given, 2016). Systematic research on information seeking (use of sources like books or newspapers) goes back a century. This mostly took the form of system-centred research (Vakkari, 1999) where information sources and how they were used were studied, rather than the individual users and their needs. The system-centred approach has motivated thousands of studies, typically evaluations of library use, information retrieval systems, interface designs, etc. (Case and Given, 2016).

In the 1970s, the field of information science underwent a sea change, shifting its emphasis from quantitative toward qualitative studies (Ellis, 2011), and away from the structured information system and toward the person as a searcher, creator, and user of information, making way for terms such as information seeking and sense making (Choo and Auster, 1993). These changes ushered in the era of conceptual model development in information behaviour that continues to the present day.

Metatheoretical approaches in user-centred research

Pettigrew, Fidel, and Bruce (2001) classify major conceptual developments in the user-centred information behaviour literature into three categories: cognitive, social, and multifaceted. Cognitive approaches cover models and theories focusing fundamentally on user attributes and knowledge structures (Belkin, 1990). Social approaches focus on the user’s social context. Multifaceted approaches cover the cognitive, social, and organisational context (see Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005).

Talja, Tuominen, and Savolainen (2005) outline three metatheories (constructivism, collectivism, and constructionism) which they say represent important and emerging perspectives on information seeking and knowledge formation in information science. Here, constructivism, in which one’s reality is constructed within the individual mind, maps to the cognitive approaches discussed above, while collectivism and constructionism (in which one’s reality is influenced by social interactions) map to social approaches.

Constructivism or the cognitive viewpoint is the dominant approach used in most user-centred information science models (Wilson, 1981; Krikelas, 1983; Wilson and Walsh, 1996; Ellis, 1989; Kuhlthau, 1991), although many cognitive models also incorporate the social and environmental context. Wilson (2016) emphasises that his models (Wilson, 1981; Wilson and Walsh, 1996) are behavioural which includes both the social and the cognitive perspectives. “From the beginning, his models have identified a wide range of factors from the psychological to the social that influence the behaviour of individuals in relation to information. However, by the very nature of any theory that seeks to explain human behaviour, a cognitive element must be present, since the recognition of a need for information by a person necessarily involves cognition.” (Wilson, 2016). Many modern system-centred frameworks emphasise the user’s cognitive viewpoint when searching (e.g. Belkin, 1990; Ingwersen, 1992).

Constructionist or social approaches have been used in more naturalistic and interpretive ways of studying information behaviour, giving rise to sub-areas like information poverty (Chatman, 1996) and collaborative information seeking (Hansen, Shah, and Klas, 2015). Social approaches (also used by Tuominen, 1997; Pettigrew, 2000; McKenzie, 2003) are less common in empirical work than the cognitive viewpoint, and fewer social models have been proposed.

Thus, the cognitive and social approaches are the two basic streams in the conceptual development of information seeking, though there are others, such as affective approaches that study the role of emotion in information seeking (Kuhlthau, 1991; Nahl and Bilal, 2007; Savolainen, 2014) and system-centred approaches. These metatheoretical streams will inform our understanding of each of the theories and models discussed in this paper.

Many researchers have incorporated both cognitive and social factors into their information seeking models, including Dervin (Dervin, 1992; Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012; Agarwal, 2012), Leckie et al. (1996), Johnson (1997), Kari and Savolainen (2003), Byström and Hansen (2005), and Karunakaran, Reddy, and Spence (2013). Such multifaceted approaches emphasise the importance of social, organisational, and situational contexts (Agarwal, 2018) on an individual’s cognitive state. Pettigrew, Fidel, and Bruce (2001) emphasise the strengths of such models over those that focus only on cognitive or social factors.

Many recent models incorporate aspects of the user as well as the system. The cognitive approach, which focuses on the interactions between user and system, is represented in the work of Brookes (1977), Vickery, Brooks, and Robinson (1987), Belkin (1990), and Ingwersen (1992). Brookes (1977) discusses the developing cognitive viewpoint in information science. Vickery, Brooks, and Robinson (1987) describe the issues involved in the construction of an expert system for retrieval. Belkin (1990) discusses why the cognitive approach may be a powerful framework for the general and practical development of information science, leading to advances in areas such as bibliometrics, user studies, the reference interview, and information retrieval. Ingwersen (1992), in his book, discusses information science as seen from a cognitive science perspective and its applications in information retrieval. Croft (1987) and Smeaton (1992) combine research aspects from both the statistical and cognitive approaches (Ellis, Allen, and Wilson, 1999). Several models following this approach exist, such as Belkin’s Monstrat Model (Belkin, 1984), Ingwersen’s Mediator Model (Ingwersen, 1992) and subsequent models (e.g., Ingwersen, 1996; Saracevic, 1996; Spink, 1997; Järvelin and Ingwersen, 2004; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Järvelin, 2007). Ingwersen and Järvelin’s research framework in their 2005 book covers both individual and social aspects of information behaviour, including the generation, searching, retrieval, and use of information. These various approaches, combining aspects of the user and the system, are important both from a research, as well as a system-design standpoint.

Prior attempts at integration

Prior researchers have realised the value in integrating key concepts from multiple information seeking models. Sonnenwald and Iivonen (1999) develop a multifaceted conceptual model for designing information behaviour research studies. Choo, Detlor, and Turnbull (2000) propose an integrated model of information searching. Bates (2002) proposes a model integrating information seeking and searching. D’Ambra and Wilson (2004) unify the concepts of uncertainty reduction and task-technology fit in a framework for evaluating Web resources. Spink and Cole (2006) integrate concepts from evolutionary psychology with models from information science, such as sense-making and everyday-life information seeking. Godbold (2006) incorporates Dervin’s (1992) concept of gaps into Ellis’ (1989) and Kuhlthau’s (1991) information seeking models. Knight and Spink (2008) combine numerous models from information seeking and retrieval in their macro model of human information behaviour on the Web. Lakshminarayanan (2010) integrates aspects of several models, as well as the results of an empirical study, in her own model of everyday-life information behaviour. Finally, Robson and Robinson (2013) bring in concepts from the fields of information behaviour and communication to create a cross-disciplinary model. Savolainen (2016b) analyses seven integrated models developed by different researchers.

Similar methodological work

Wagner and Berger (1985) propose a framework to analyse theory growth in sociology by looking at theoretical activity at the level of sets of related theories, which they call theoretical research programs. Within these programs, they see at least five different types of relations among theories, each representing a different form of theoretical growth. Their relation of interest in this study is theory integration. Here, a new theory may emerge which incorporates much of the conceptualisation of two or more theories, when each theory suggests very similar ways of dealing with the same sociological problem. Kuokkanen and Savolainen (1994) write that theory integration leads to parsimony or the economy of knowledge.

Kuokkanen and Savolainen (1994) build on Wagner and Berger’s work and propose a structuralist theory of science as an alternative framework to serve as criteria for identifying theoretical continuity.

Using Wagner's and Berger's model and Kuokkanen’s and Savolainen’s (1994) tools for comparing the similarity of theoretical structures, Vakkari (1998) analysed the growth of a theoretical research program in information seeking studies, by reconstructing the logical structure of theories within the program, and by comparing those reconstructions in terms of their conceptual and factual similarity. He argues that the analysis of theoretical growth “does not presuppose consciously formed programs”, or “creating intentional research programs”, but that “it is possible to analyse theoretical progress by interrelating separate studies that overlap conceptually and factually”. (p.363) This argument applies to this paper. Vakkari concluded that the growth pattern is elaborative.

Other works on the analysis of growth in theories, using theoretical research programs or inter-related theories, can be found in Berger and Zelditch (1993) and Berger, Willer, and Zelditch (2005). Pettigrew and McKechnie (2001) analysed 1,160 articles published between 1993 and 1998 for the use of theory in information science research and found that theory was discussed in 34.1% of the articles. Vakkari (2008) finds that scholarly attention has gradually shifted in recent years from theoretical studies of information seeking behaviour, to more qualitative studies of personal habits related to information seeking. He concludes that the homogenisation of research approaches in information behaviour challenges scholars to pursue more varied theoretical approaches. Jansen and Rieh (2010) compare, and contrast, seventeen theoretical constructs for the fields of information searching and information retrieval and find a trend towards convergence of the fields. Julien, Pecoskie, and Reed (2011) conducted a content analysis of information behaviour articles published between 1999 and 2008. They observe increasing levels of interdisciplinarity in scholarship on information seeking behaviour and acknowledge the benefits of diverse perspectives in the field.

Despite all this prior work, Savolainen (2016a) laments the scarcity of conceptual analysis in information science and attempts to clarify the concepts in information behaviour, building on Bates’ (2002) integrated model. Savolainen (2016b) analysed seven integrated models of information behaviour for conceptual growth. He found that researchers have employed four main approaches to developing integrated models: 1) juxtaposing individual models; 2) cross-tabulating the components of diverse models; 3) relating similar components of individual models; and 4) incorporating components taken from diverse frameworks. Savolainen (2017a) conducted a conceptual analysis on nine key studies elaborating on Ellis’ (1989) model and found that the studies elaborated on Ellis’ model using two approaches: adding novel, context-specific components in the model and redefining and restructuring the components. Savolainen (2016b) and Savolainen (2017a) both conclude that the integrated models and elaborations have contributed to conceptual growth in three major ways: 1) integrating formerly separate parts of knowledge; 2) generalising and explaining lower abstraction-level knowledge through higher-level constructs; and 3) expanding knowledge by identifying new characteristics of the phenomenon of information-seeking behaviour.

From all this, we find that the only work that has analysed conceptual growth and integrated models in information science is that of Savolainen (2016a, 2016b, 2017a, 2019). However, Savolainen limits himself to certain models. This particular paper attempts to provide a more comprehensive view by analysing models from the 1980s onwards, as well as the integrated models, and also provides a unified model.

Method

My major influences in learning about the key information seeking theories, models, and frameworks in this field were Wilson (1999); Case (2012) and the two earlier editions, and Case and Given (2016); Fisher, Erdelez, and McKechnie (2005); and the work of specific researchers. These were chosen because these sources, especially Donald Case’s book, have been instrumental in bringing together various theories and models in one place, and serve as a good starting point. Newer models were found through citation tracking. Reviewers’ comments on the revisions of this paper also led to the inclusion of models.

The second endeavour was to decide which of many theories and models to include in the unified model. Here, the models included were the ones that emerged within the field of information behaviour (though the originators of these models were influenced by ideas from various fields such as psychology, philosophy, or sociology). Among these, the ones included were those that were consistently cited in the literature. Many of the included models fit the criteria for conceptual models suggested by Järvelin and Wilson (2003). The desirable traits for models according to these criteria included: simplicity; accuracy; broad scope; ability to organise concepts, relationships, and data in a meaningful systematic way; explanatory power; ability to provide valid representations and findings; and ability to suggest problems for solving. Though not fool proof, these considerations would ensure that the major models are included. Whilst other efforts, such as that of Savolainen (2016a, 2016b, 2017a), have included a more limited set of models, I endeavoured to cast a wider net and include as many models as possible. This would allow the unified model arrived at to be more representative of the field. It would also enable new researchers to be familiar with major prior efforts. While I tried to be as exhaustive as possible within the confines of a paper, my focus was to suggest a method of mapping models and theories to find synergies and contradictions within them. This could be done by examining which constructs and variables were included across models, which were unique to different models, and if similar or different labels were used to denote the constructs in different models. Thus, this paper should be viewed more as a process than a product.

In constructing the unified model, I considered three groups of models: 1) those that emerged in the 1980s and the 1990s as the user-centred focus in information behaviour gained prominence; 2) those that built upon these from the year 2000 onwards (with technological developments like Web 2.0, social media and mobile computing influencing information behaviour); and 3) integrated models, especially from the last decade or so. In the first two groups, time is used as a differentiator, while the third relates to a different type of models that synthesise prior models. Using time or chronology to sample the models allowed me to include models from different periods. This was done to minimise the selection bias towards older and more established versus newer models. It also reveals the progress in model-building over time, as concepts in the field became more established, and newer technological developments enabled behaviour change in people.

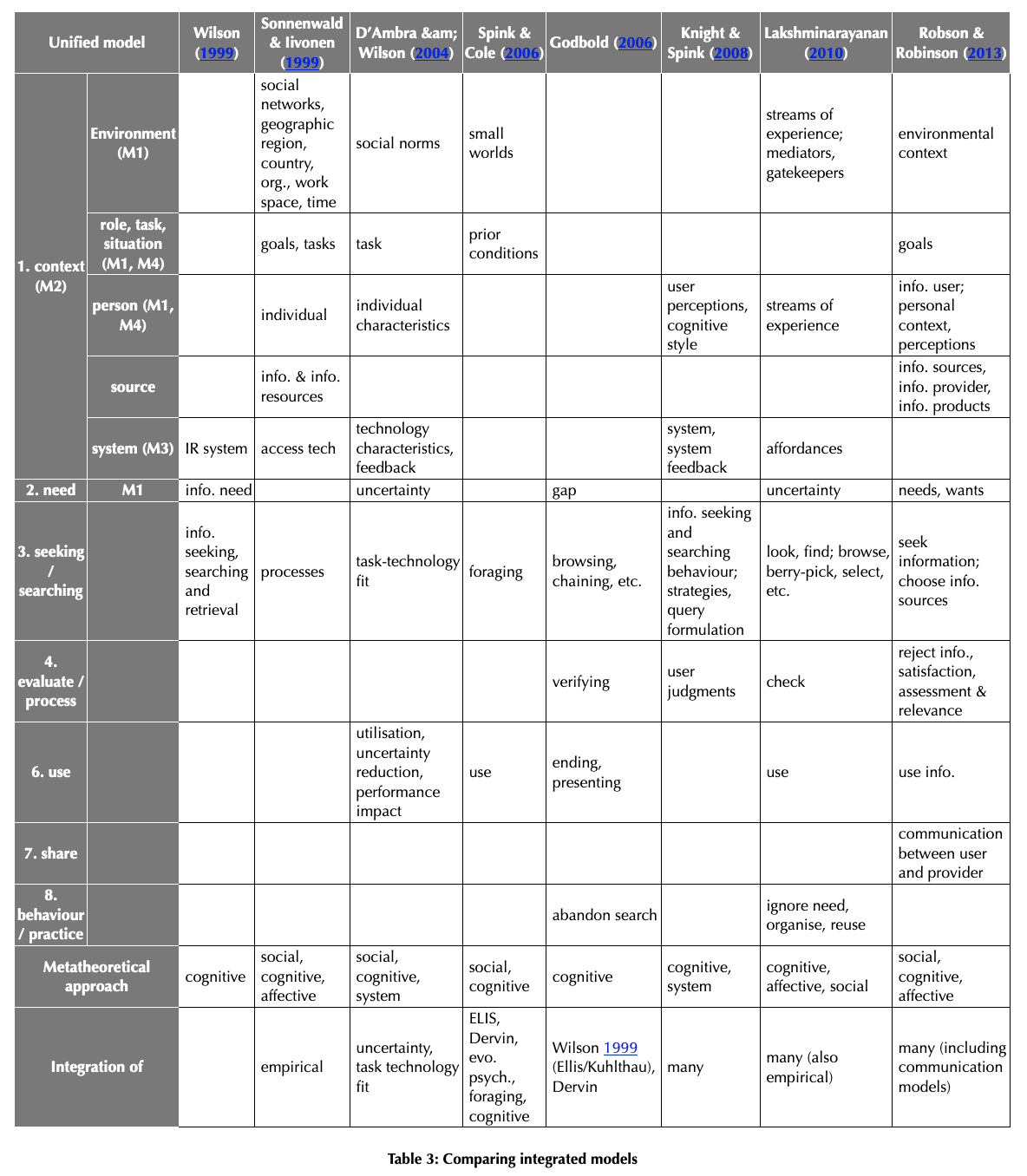

The identified models from each of these groups were put into their respective tables (see Tables 1, 2, and 3), with a mapping of the common (or distinct) elements from each of the models. For example, I put the elements of Wilson’s (1981) model as a column in Table 1. I then took Krikelas’ (1983) model as the next column in the table, with the elements in Krikelas’s model placed in rows that best matched those in Wilson’s model. I repeated the exercise for other chosen models (Dervin, 1992; Ingwersen, 1992; etc.), creating a new column in Table 1 in each case, and mapping the elements of these models to those from earlier models already in the table. The unified subset of these elements was then used to create the unified model (the first column in Tables 1, 2, and 3.). In the tables, M1, M2, M3, and M4 are moderating variables (discussed in Figure 2 and Table 4 in the next section). Moderating variables or moderators affect the relationship between the independent (cause) and dependent (effect) variables, and specify the conditions under which the relationship between the independent and dependent variables might hold (see Agarwal, Xu and Poo, 2011 for examples). Moderating variables are a central concept in the proposed unified model and I distil all information seeking models down to these core moderating variables. This is because these variables bring together various concepts e.g., environment, task, person, and need variables affecting the relationship between any two aspects in the model (e.g., information need and information seeking). A person might decide to look for information only when the task is important (task variable) or when the person is motivated to seek (person variable). This is similar to the use of intervening variables by Wilson in his 1996 model (Wilson and Walsh, 1996).

The blank cells in Tables 1, 2, and 3 have a useful purpose as well. They denote those elements of the unified model that are missing, or not addressed, in the respective individual models or integrated models covered in the tables.

A major exercise at this stage to determine if two different terms in two models were equivalent or not was still useful. For example, is need from Wilson (1981) equivalent to gap from Dervin (Dervin, 1992; Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012)? Their equivalence is based on their basic function within each model, not necessarily based on an exact match between the understandings of the different researchers. The focus was on trying to find the common ground among the various theories and metatheories, and not to imply that there is no difference. Thus, the terms were equated when they were sufficiently like each other (e.g., gap and uncertainty both relate to need) and distinct from the other components of their respective models and the parts of the unified model. It needs to be recognised that bringing together elements from different models in a single row of Tables 1-3 is limited because of the nature of best matching, and the validity of the content of the categories, or factors, created would need to be further tested.

The next step was to map every element of each model to a corresponding part of my unified model (as shown in the left-hand column of Tables 1-3) and to decide on the placement of these elements within the unified model (Figure 2). This was done by systematically building upon some of the earlier models (especially the cognitive ones) starting from Wilson (1999)’s nested model and other models of that era. Deviation from the placement of these elements in the major models of the 1980s and 1990s was done only when necessary, and not simply for the sake of being different. When a particular element was in very different places in different models, the author chose a placement based on the logical flow of the unified model.

While the steps in the method are laid down, they were not always sequential. The process was like the principle of hermeneutics as explained by Klein and Myers (1999), in which one iterates back and forth between the whole and the parts that form the whole. The elements of each model informed my creation of the unified model. The unified model, in turn, informed the way I grouped the various elements from the individual models. Thus, this non-sequential iteration is an important and recommended part of the process.

When designing, I tried to keep the unified model simple to ensure parsimony. I was aiming for completeness without overwhelming, and for usefulness more than comprehensiveness. The purpose was to work towards the criteria for conceptual models as laid out by Järvelin and Wilson (2003). I then chose examples of models from my three subsets to demonstrate how the elements in each model map to those in the unified model.

While the exercise of demonstrating mapping through figures is useful, it would become redundant at some point. Thus, representative examples were drawn from those in the three tables to be included for further explanation. For the example figures in the following section, I included two of Wilson’s models (Wilson, 1981; Wilson and Walsh, 1996) as they include the basic steps in the seeking process, as well as moderating variables affecting seeking. Dervin and Foreman-Wernet (2012) was included to incorporate the messiness of real-life seeking. Ingwersen's (1996) model represented the systems side of information seeking. McKenzie (2003) represented the constructionist viewpoint. Niedźwiedzka (2003) was added as she includes seeking through intermediaries, while Karunakaran, Reddy, and Spence (2013) brought in collaborative seeking. Agarwal, Xu and Poo (2011) focused on context. From among the integrated models, Knight and Spink (2008) was included as it is web-based and explicitly identifies past models it incorporates. Lakshminarayanan (2010) includes a wide array of information-related activities, while Robson and Robinson (2013) incorporates both communication and seeking models. Thus, while not exhaustive, the chosen models represent a good variety of viewpoints. This variety of viewpoints, such as messiness of real-life seeking, systems-side, constructionist viewpoint, etc. emerged organically during model building and were not there a priori.

Table 1: Comparing models (1980s and 1990s) Click for large version. |

Table 2: Comparing models (2000 onwards) Click for large version. |

Table 3: Comparing integrated models (2000 onwards) Click for large version. |

A unified model of information seeking behaviour

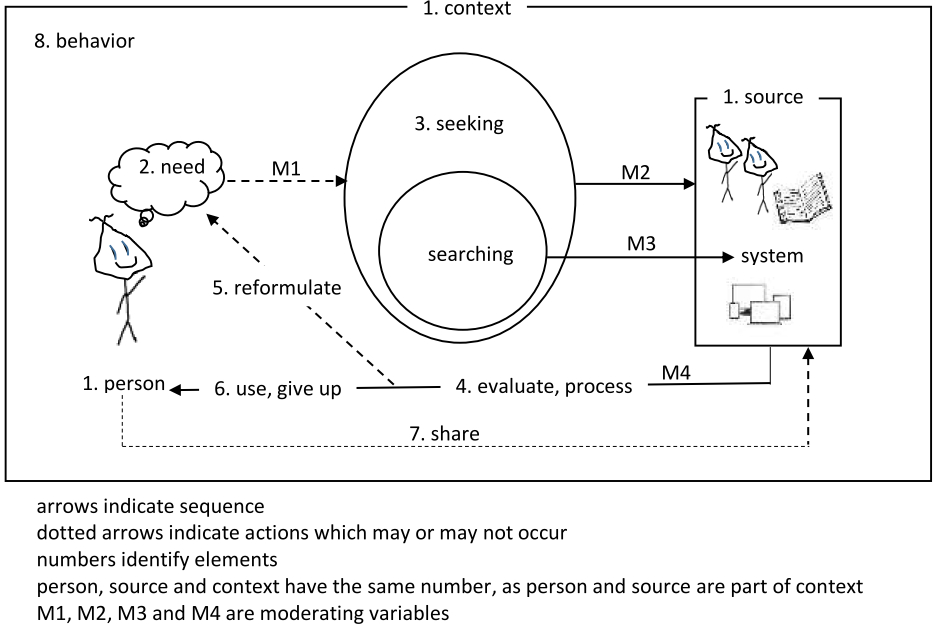

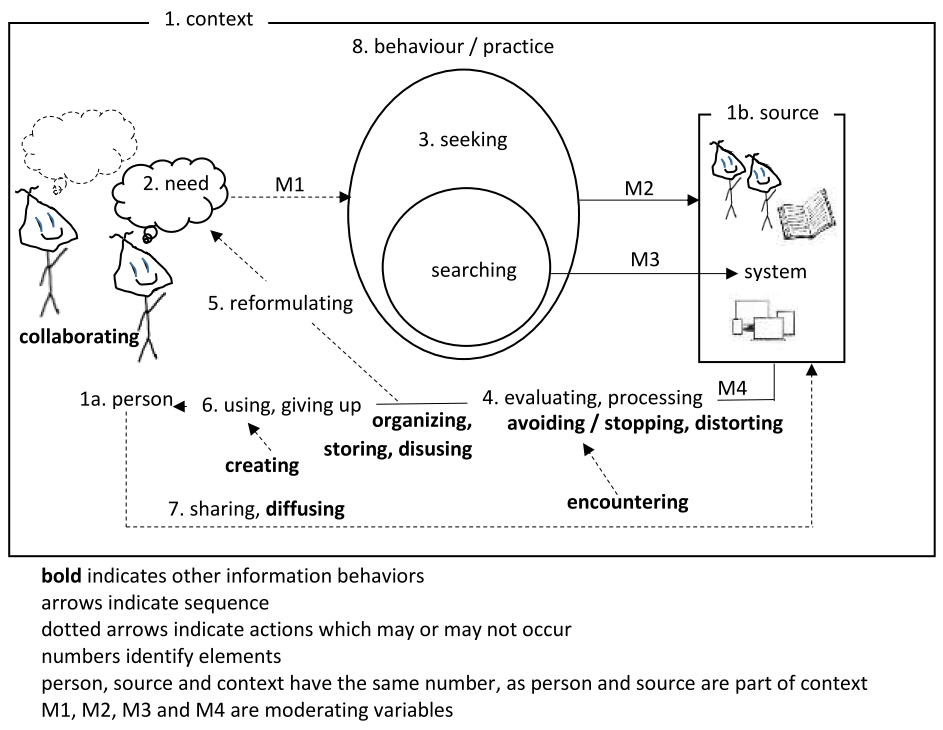

Figure 2 shows the unified model of information seeking. The model expands the adapted nested model of Figure 1 to include the elements from all models listed in Tables 1-3.

-

Context (including person and/or source). In the figure, context refers to the multitude of factors that may give rise to a person’s need for information, which might get them to start looking for the needed information. These factors can include the person’s physical environment, factors relating to the person themselves (thoughts, value system, cognition, experience, etc.), the role, task or situation, as well as the sources or system that the person has access to. It is to emphasise this multi-faceted nature of context (which might seem to reside in different places, but which can all inform information need) that I use the same number (1) to label the person (1a), source (1b) and the context.

The model emphasises the prime importance of context in every stage of seeking. Seeking takes place within a person’s larger context (1), including environmental, organisational, social, and task-related variables. Within this context is the entirety of the person’s information behaviour or information practices (8)—not only seeking, but also information avoidance, creation, information encountering, etc. I include both behaviour and practice in the model as these are both umbrella terms used in the field (see Savolainen, 2007). Personal characteristics (1), such as demographics, knowledge, experience, emotions, and cognitive style, also contribute to their context. (The person is represented in Figure 2 by Dervin’s (1992) Mr. Squiggly). It has to be understood that context doesn’t exist in isolation and “isn't just there” but is always tied to a behaviour or activity i.e., the actor engaged in information behaviour (Dourish, 2004). Context is always created at the point of interaction of the actor with information from a source mediated by some channel e.g., computer or mobile device or face-to-face. “Thus, context is of the actor engaged in an activity at the point of interaction.” (Agarwal, 2018, p.125)

Need and M1. The person’s context gives rise to a need (gap (Dervin, 1992), ASK (Belkin (1980), etc.) (2), which the person may or may not address. This decision is influenced by a set of moderating variables (M1) relating to the environment, task, person, and to need itself (its urgency and importance).

Seeking and/or searching and M2 / M3. If the person decides to address their need, they begin the seeking process, of which information searching is a subset (3). Seeking may have different modes, such as active or passive (Wilson and Walsh, 1996), take place in multiple stages (as in Kuhlthau, 1991), and require different strategies and cognitive activities (Ellis, 1989). The various information sources available, including people, printed materials, websites, etc., also form part of the context (1). The person’s choice of source(s) is moderated (M2) by all the variables under M1, but also the characteristics of the source, such as channel, quality, and ease of use (Agarwal, Xu and Poo, 2011). If the person is performing a search on a computer system, their behaviour will also be affected by variables of the system (M3), including the interface, database structure, task-technology fit, and the person’s system knowledge (Ingwersen, 1992, 1996; Saracevic, 1996).

Evaluate, process and M4. Once the person receives information, they must evaluate and process it (4). The relevance of information is determined by the requirements of the task at hand and the characteristics of the person (M4).

Reformulate. If the information is insufficient to satisfy the person’s need (a new situation in time or space as per Dervin, 1992), they may choose to re-evaluate and reformulate their expressed need (5), starting the process again.

Use and/or give up. This cycle (as per Spink, 1997) repeats until either the need is satisfied or the person gives up (6). If the new information satisfies the person’s need, they put the information to use (6), which may in turn lead to a new need.

Share. They may also choose to share the information with others in their environment (7).

Behaviour and/or practice. As discussed under context above, information behaviour or practice denote the umbrella terms for information seeking, avoiding, finding, etc. under which all the above activities take place, and is tied to context.ß

Figure 2 reveals the commonalities among the models I surveyed. In Table 4 below, I expand each element of the unified model, showing how I reconciled these various understandings but also emphasising the different approaches and terminology used within the field of information seeking.

| 1. context |

Variables of:

|

|---|

Integrating existing models into the unified model

In each of the figures below, the model on the left represents the model from which the elements of the unified model (at right) are derived. For a deeper explanation of those models, the reader should refer to the referenced papers. The focus here is on the comparison of elements between those models and the elements of the unified model. The numbers indicate corresponding elements of the models.

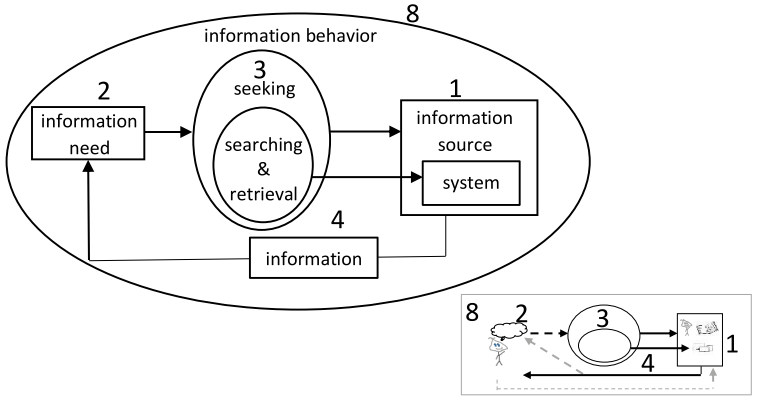

Figure 3: Mapping to Figure 1 (derived from Wilson (1999)’s nested model)

Figure 3 maps the unified model to the nested ellipse model shown in Figure 1 (derived from Wilson (1999, p.263)). While I include information in Figure 1 for simplicity, it corresponds to evaluate, process [information] in the unified model.

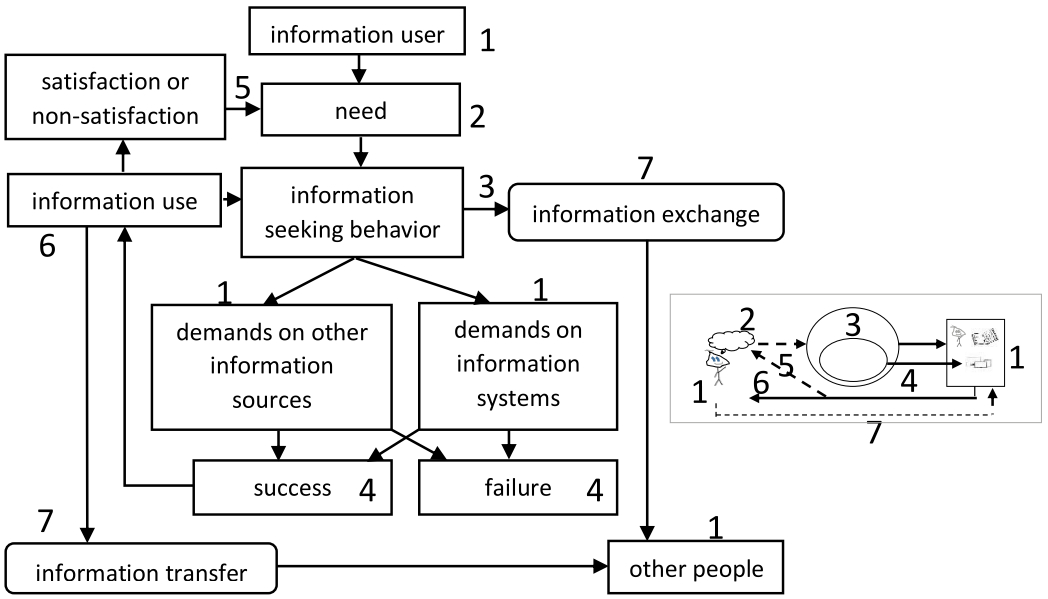

Figure 4: Mapping to Wilson’s (1981) model of information behaviour

Figure 4 maps Wilson’s (1981) model of information seeking to the unified model. It includes the concepts of information user, use (which had received little attention until then), exchange, and informal transfer of information between individuals. However, there is no arrow from failure to need (the process typically repeats when a search fails to satisfy the need). Also, there is no suggestion of context or causative factors, and it does not directly suggest hypotheses to be tested (Wilson, 1999).

Wilson (1981) took a critical stance toward the term information need and preferred physiological, affective and cognitive needs as triggers of seeking. Thus, the word need (2) in the unified model (as opposed to information need) corresponds to Wilson more closely. The success and/or failure components in Wilson’s model map to evaluate and/or process (4) in the unified model; the arrow between satisfaction or non-satisfaction and need can be likened to reformulation (5); information transfer in Wilson’s model maps to sharing (7). Information exchange has elements of sharing and seeking; thus, it is identified with 7, with a 3 over the arrow leading to it. As seen from the mapping, Wilson’s (1981) model does not include information behaviour (8) or context (1).

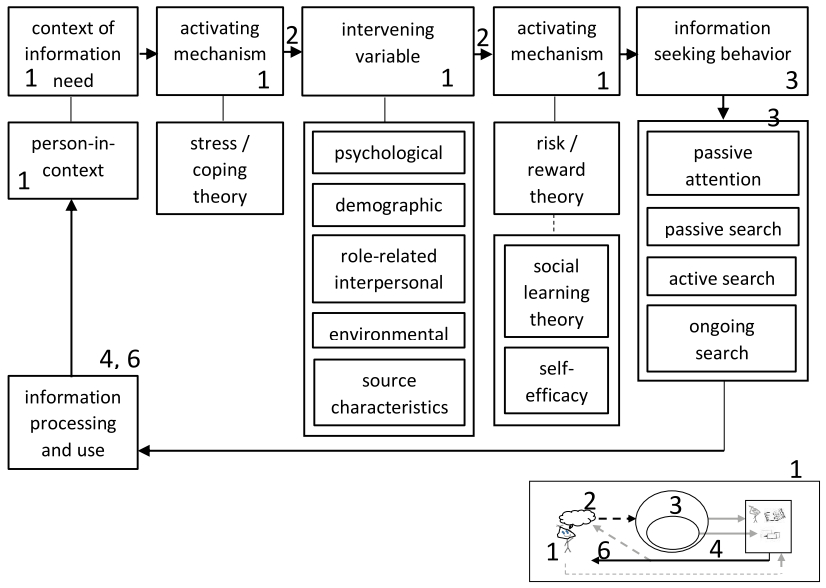

Figure 5: Mapping to Wilson and Walsh (1996)

Wilson and Walsh’s (1996) model of information seeking emphasises the context of seeking (Figure 5) and invokes explicit theories to explain different stages of seeking. Wilson and Walsh’s activating mechanisms are motivators, affected by intervening variables. The model also recognises that there are different types of seeking. Wilson’s inclusion of other behavioural models makes it a richer source of hypotheses compared to his 1981 model (Figure 4) (Wilson, 1999; Case and Given, 2016). In the unified model, Wilson and Walsh’s activating mechanisms and intervening variables correspond to context variables of the person, environment, task, and source (1). While need (2) is not explicitly mentioned by Wilson and Walsh, it is implied to be triggered by the activating mechanism and affected by the intervening variables. Wilson has since further expanded his model to include intentional and accidental modes of information discovery between activating mechanism and information seeking behaviour in Figure 5 above (see an expanded model in Wilson, 2020, p.42).

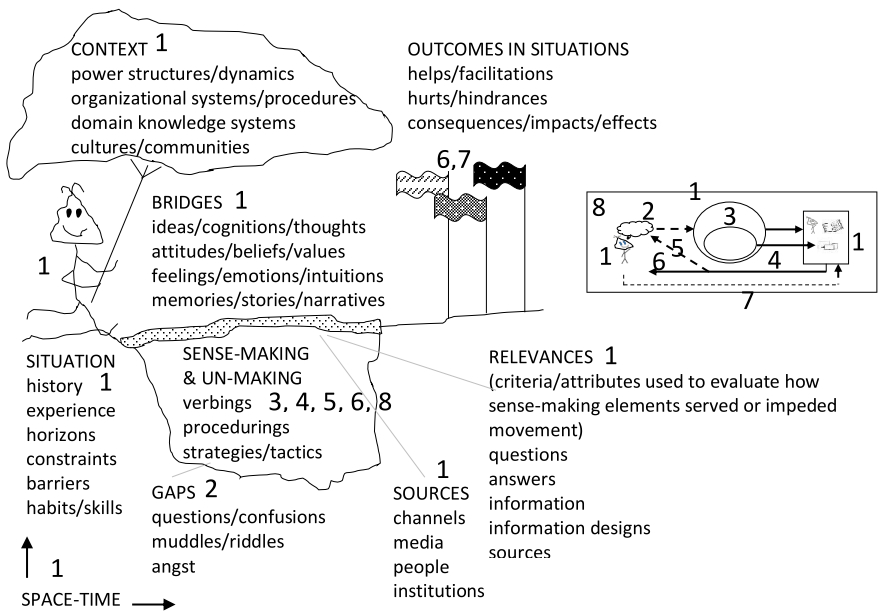

Figure 6: Mapping to Dervin’s sense-making methodology (Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012)

Another well-known information behaviour model is Dervin’s sense-making methodology (Dervin, 1992; Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012; Agarwal, 2012). It proposes that information is not “something that exists apart from human behavioural activity”. Rather, it is “created at a specific moment in time-space by one or more humans” (Dervin, 1992, p.63). Unlike other approaches that see information as something out there that is transmitted to people (as Dervin says, an information brick put into a human bucket), sense-making sees information as construed internally to address gaps or discontinuities (Agarwal, 2012). In the same spirit, I do not include information as a separate thing (Buckland, 1991) in the unified model. Rather, I emphasise the process and context.

In the unified model, sense-making maps to all those activities related to seeking, obtaining, evaluating, processing and using information (3, 4, 5, 6, 8) which build a bridge over the gap (2), corresponding to a change in the person’s individual context (1). The bridge itself, comprising the individual’s thoughts, feelings and memories, constitutes part of the context (1), as do source characteristics and relevance criteria. Dervin’s outcomes map to information use and sharing (6, 7).

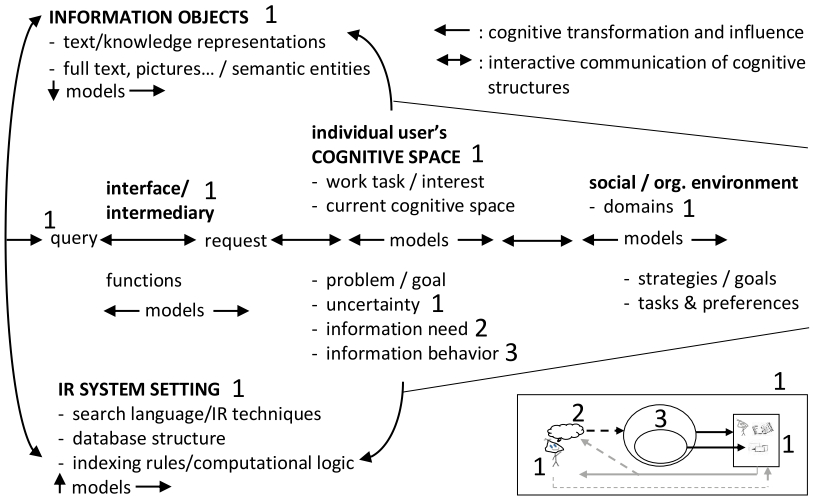

In his 1996 model (Figure 7), Ingwersen identifies processes of cognition that may occur during interaction with an information retrieval system. The elements user’s cognitive space and social and organisational environment resemble the person-in-context and environmental factors of Wilson’s models. The queries posed can be related to Wilson and Walsh’s active search (see Figure 5). The strength of the model is that it integrates ideas relating to seeking and needs with issues of information retrieval system design. The weakness is that it does not provide for testability or for evaluation of information retrieval systems (although Borlund and Ingwersen (1997) have developed an evaluative strategy based on this model) (Wilson, 1999).

In the unified model, the features of the interface, information retrieval system setting and information objects all map to the contextual variables of source and system (1), as the user’s cognitive space and models map to the personal context. I take Ingwersen’s information behaviour to refer strictly to seeking and/or searching (3), given the model’s system focus.

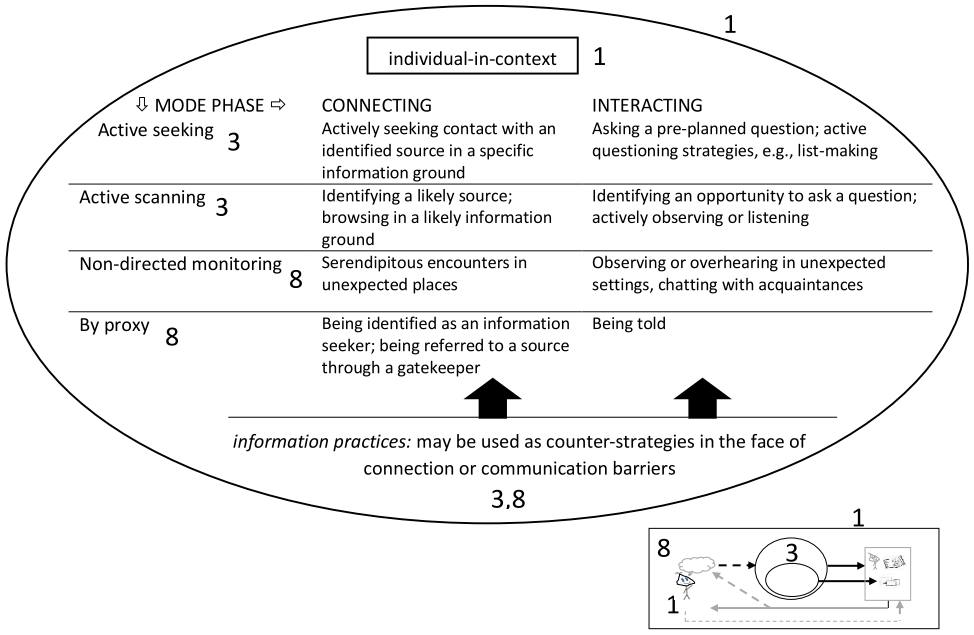

Figure 8: Mapping to McKenzie (2003)

McKenzie (2003) provides a social constructionist model of everyday-life information seeking by studying the information practices of women pregnant with twins (Figure 8). Her model is two-dimensional, which she considers more flexible at describing people’s actual behaviour than the typical process models in information seeking studies. A person may engage in four different modes of information practice, and each mode may proceed through two phases. Both phases may involve barriers to communication depending on the context.

In the unified model, active seeking and active scanning constitute two strategies in the seeking process (3), while non-directed monitoring and by proxy are part of the broader category of behaviour (8). Because my model deals specifically with information seeking, it creates a divide between seeking and other information-related activities that may be artificial.

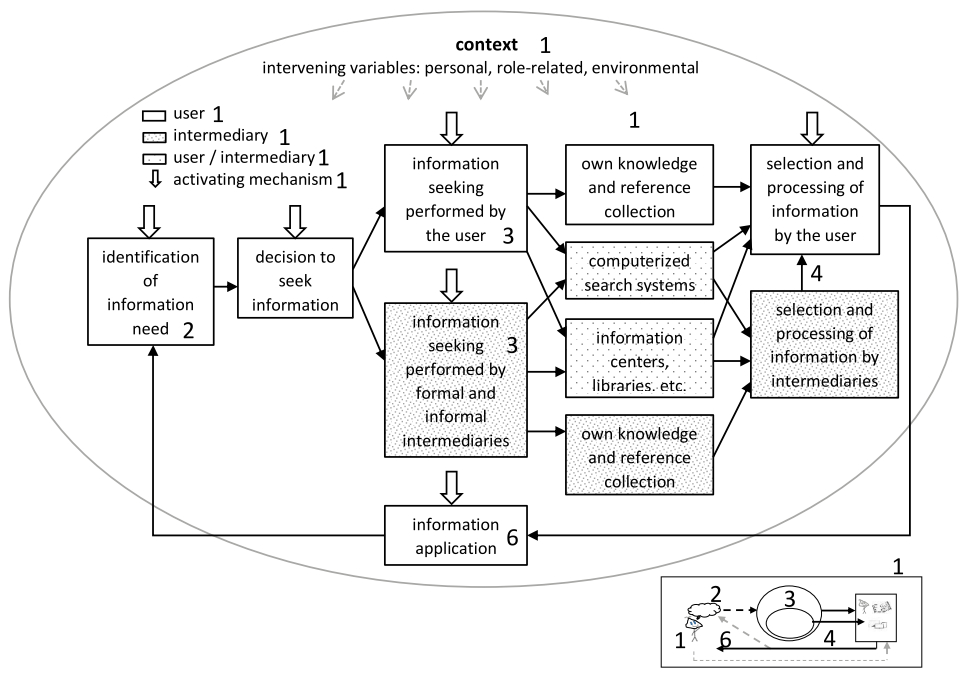

Figure 9: Mapping to Niedźwiedzka (2003)

Niedźwiedzka (2003) presents a critique and adaptation of Wilson and Walsh’s model (see Figure 5), based on her research of managers in Poland (Figure 9). Her model keeps the core concepts of Wilson and Walsh, but elevates the importance of context (including activating mechanisms) to show its effects on all stages of seeking and introduces the use of intermediaries.

In the unified model, the intermediary, just like the user, is considered part of the context (1), since their beliefs, knowledge, etc. will affect the seeking process. The use of an intermediary is a type of seeking strategy (3), where the seeker must evaluate and process the information provided by the intermediary (4). Niedźwiedzka (2003) suggests that Wilson omits the idea of an intermediary acting for the searcher in his models. However, in Wilson (1981), one of the figures on the context of information seeking includes a mediator along with user, technology, and information resources.

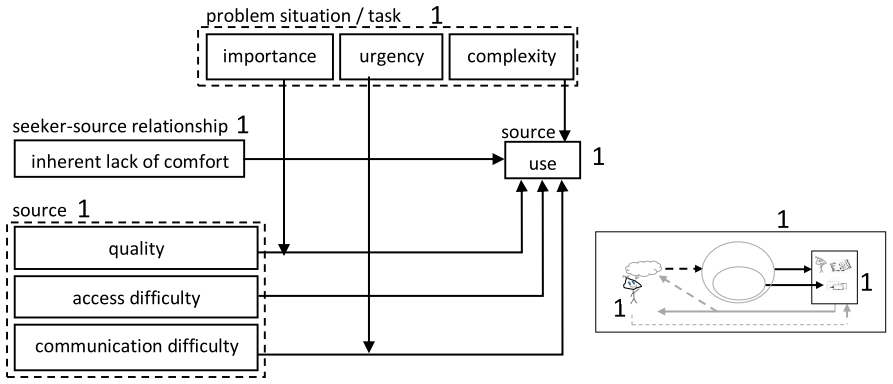

Figure 10: Mapping to Agarwal, Xu and Poo (2011)

Through a survey of 352 working professionals, Agarwal, Xu and Poo (2011) built upon their earlier work on context (Agarwal et al., 2009) to study the effect of contextual variables of the seeker, source, task, and seeker-source relationship on the use of an information source (see Figure 10). They found source quality (and some other variables) to have a significant effect on source use. The model focuses almost entirely on context, which maps to (1) in the unified model.

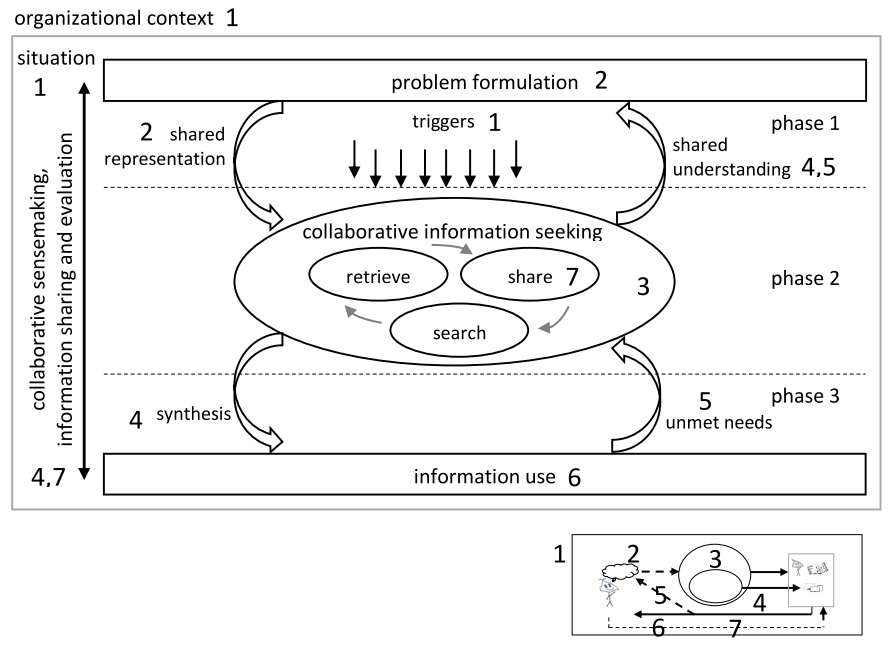

Karunakaran, Reddy, and Spence (2013) propose a model of collaborative information behaviour, based on empirical evidence from organisational settings (Figure 11). Their model comprises three phases. Problem formulation requires that the group agree on a shared representation of the problem. Collaborative seeking involves a cycle of three activities. During the seeking process, the group may change its shared understanding of the problem. Finally, the group must evaluate, synthesise and use the information. If any needs remain unmet, the group may return to the seeking cycle. Throughout the process, the group engages in collaborative sensemaking, information sharing and evaluation.

In the unified model, problem formulation and shared representation map to need (2), triggers map to moderating variables (1), and the modification of shared understanding maps to information evaluation and need reformulation (4, 5). As the unified model focuses on individual seekers, it does not capture the fact that information sharing occurs at all parts of the collaboration, not only after information is found.

Existing integrated models and their mappings to the unified model

In the past two decades, many researchers have combined elements from earlier information seeking models to create richer, more comprehensive models. To create a unified model, it was important to integrate not just the individual models, but the integrated models as well. This ensures that significant past work in model building and synthesis is not ignored.

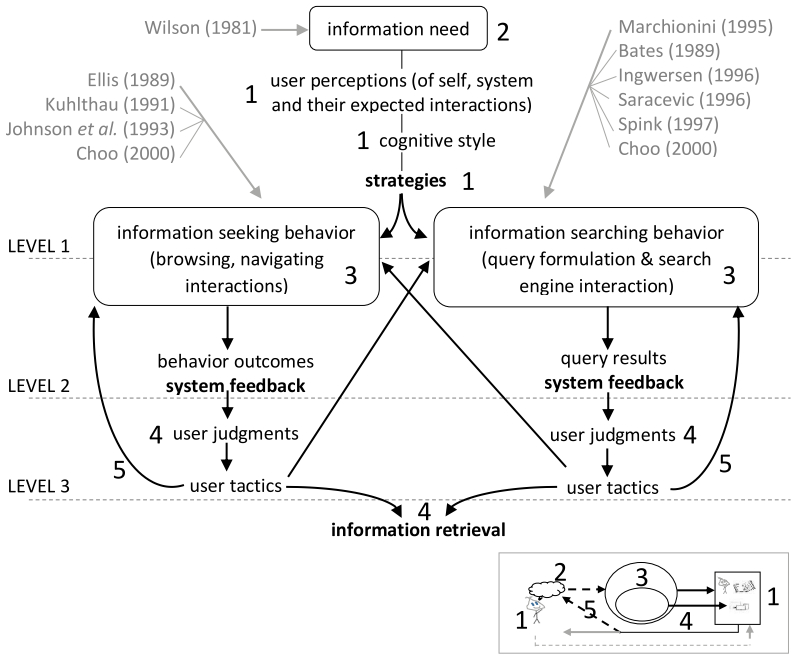

Knight and Spink (2008) present a model of web-based seeking and searching behaviour. As shown in Figure 12, it involves elements from several well-known models, on both the user and the system side. The user’s cognitive style and perceptions of the system affect their seeking strategies. Knight and Spink distinguish browse-seeking (left side) from search-seeking (right side), which each involve different actions. They also emphasise the impact of intervening variables on the cycle of seeking and evaluating outcomes.

Knight and Spink’s user perceptions, cognitive style and strategies all map to personal context (1) in the unified model. User judgments correspond to processing and evaluation (4), which can lead to acceptance of the information, or a return to the search, which corresponds to reformulation (5).

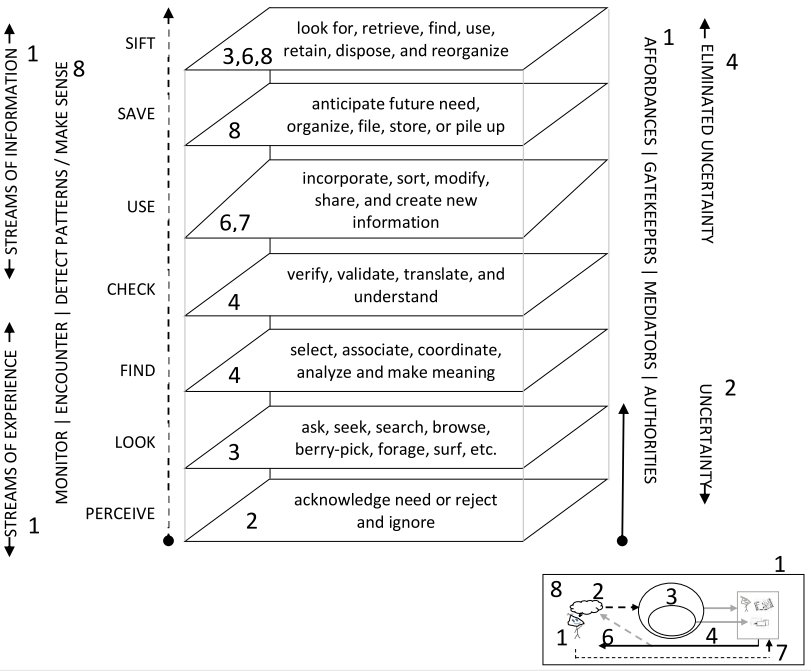

Lakshminarayanan’s (2010) integrated model is the result of an empirical study of the everyday-life behaviour of thirty-four subjects, incorporating insights from the information behaviour literature. She notes the importance of personal and social context as a mediator that affects all behaviour and “through which the different information processes can take short-cuts between the stages, backtrack, bypass some stages, or abandon information seeking” (pp.307-308).

Lakshminarayanan’s streams of experience, streams of information and affordances/gatekeepers/mediators/authorities all map to context (1) in the unified model. She lists several seeking strategies, such as browsing, berry-picking, etc., that fall under seeking (3) in my model. Her find and check categories correspond to information processing and evaluation (4). The model also includes several activities besides seeking, such as organising, disposing, and encountering (8).

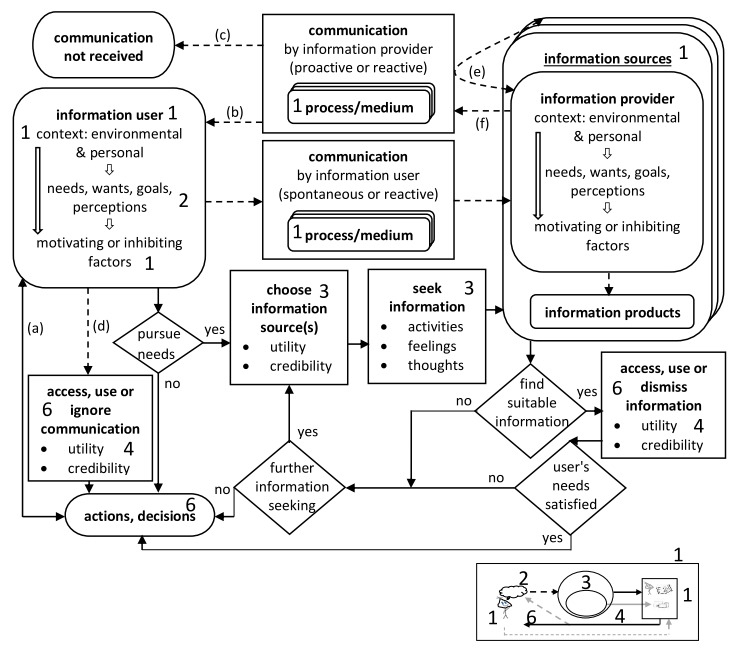

Robson and Robinson (2013) integrate several information behaviour models, including those of Leckie et al. (1996), Johnson (1997), Wilson and Walsh (1996), etc. with models from the field of communication. The distinguishing feature of this model is that it envisions information providers as active participants in the seeking process, with their own contexts and goals, and capable of communicating with seekers and with each other.

This symmetry in Robson and Robinson’s model is reflected in the unified model, where both the person and source are considered part of the context (1). Communication by the provider can also be considered a context variable of the source.

Discussion and implications

We have looked at several models of information seeking and behaviour, including integrated models, and their mappings to the unified model. Based on the preceding sections, we can safely deduce that we managed to capture the major elements and the overarching essence of these models in the unified model. Tables 1, 2, and 3 have shown the major elements from each model and how they map to the unified model. The blank cells in the tables indicate the components of the unified model that are not directly addressed in the models studied. All the major elements of the individual models are either directly included, or implied, in the columns of these tables.

We also sought to find common ground between the different metatheoretical assumptions and approaches in information science. In the process, I have sought to keep the model simple. Simplify and parsimony are “not only the end product of scientific activity, but. also [help] to guide” theories and models and their testing and verification (Simon, 2001, p.39). This simplicity and parsimony (while ensuring coverage and quality) is one of the strengths of the unified model. This contrasts with several previous integrated models, which have been more complex.

The method of comparing elements of models with those in the unified model is also important as a prototype of a methodological move, which may be replicated by other researchers seeking to integrate models in their research fields. This process of mapping and synthesising helps bring about convergence of research and an understanding of where a common direction unfolds, and where it does not. (I discussed some such mismatches in Section 5, e.g., when discussing McKenzie (2003) and Karunakaran, Reddy, and Spence (2013)). It allows researchers to engage more proactively in charting the forward movement of a field.

The strength of the unified model lies in the fact that it combines several important contributions made in the field of information seeking in a single model (in Figure 15, I extend the unified model to include modes of information behaviour other than seeking). The model(s) can be viewed as a unification of past integration efforts, paving the way for subsequent studies, refinements and greater synthesis in the years to come. It shows researchers in information seeking one possible way of moving forward, so that they can work towards their common goal of meeting the needs of users and knowledge workers.

Some key implications emerged in the process of synthesising models. Firstly, while most models and frameworks had the basic elements of need and seeking, most of the important and interesting elements in later models were related to context. These constituted the intervening variables in Wilson and Walsh (1996), context, situation, etc. in Dervin and Foreman-Wernet (2012), social and/or organizational environment in Ingwersen (1996), and the individual-in-context in McKenzie (2003), among others. Agarwal, Xu and Poo’s (2011) model focused exclusively on context. These elements of context map to the moderating variables M1-M4 in the unified model. As can be seen from Table 4, context constitutes a whole body of elements, including variables of the environment, situation, person, source or system and time. Thus, future work in the areas of information seeking and behaviour should continue to have context as a central component, especially to tease apart the relationships between various context variables. This was also concluded by Ingwersen and Järvelin (2005) and Agarwal (2018).

Secondly, other information activities, besides seeking, are becoming increasingly studied, as seen in McKenzie (2003) and Lakshminarayanan (2010). These include encountering, creating, organising, storing, using, and sometimes disusing or divesting information. Information avoiding, non-response, and stopping will also be important, as people struggle with the avalanche of information thrust upon them, or choose not to respond to messages sent using smartphones (see Agarwal and Lu, 2020). Also, the disinformation, misinformation, and fake news phenomenon has brought to light how individuals might distort information or forward, spread, or diffuse such information on social media (see Agarwal and AlSaeedi, 2021; Erdelez, Agarwal and Jahnke, 2019). Thirdly, whilst most models and frameworks reviewed have focused on the individual seeker, another area of study examines collaborative groups as seekers (as seen in Karunakaran, Reddy and Spence, 2013). Having more than one seeker brings in important new considerations. These include communication at all levels, which requires reaching a common ground at different stages. For an individual, this would be akin to reconciling one’s own thoughts and reaching a decision. Last but not the least, models will emerge that relate information behaviour to other fields. This can be seen in Robson and Robinson (2013), where information behaviour is linked to the field of communication. Models can be created linking information behaviour to fields such as knowledge management, human-computer interaction, informatics, etc. In Figure 15, I extend the unified model to include other modes of information behaviour (indicated in bold). The verbs evaluate, process, reformulate, use, give up, and share are modified to end in ing to indicate them as types of information behaviour, rather than as part of the process of information seeking behaviour in the unified model.

On a more practical level, the tradition of research into information retrieval considers information seeking from a systems perspective and information users as passive, situation-independent receivers of objective information (Dervin and Nilan, 1986). By bringing together the key concepts in the study of the user and their search for information into one model, the unified model can aid system designers and developers in the design of context-aware search engines. While designers would still need to interview and study specific users and their needs, the unified model can serve as a theoretical foundation towards that data gathering.

Table 4 lists specific variables for different components in the unified model. Agarwal (2018, pp.105-106) also lists variables that can be mapped to different context elements – environment, task/activity/problem situation, need, information required, actor, source/system/channel, actor-source relationship, and time/space. We see from Figure 2 (or Figure 15) that M1 sits on an arrow linking need and seeking. From Table 4, or from the listing in Agarwal (2018), we could pick any variable for M1, and come up with a hypothesis from Figure 2 linking need, the variable we picked for M1, and seeking. For example, if we picked emotional state as an actor variable for M1, we could come up with a hypothesis linking need, emotional state, and seeking. It could be worded as, An actor’s need for information from a spouse or partner will vary based on the emotional state of the actor at that point in time. Similarly, innumerable hypotheses could be developed by picking any term from Table 4 (or the listing in Agarwal, 2018) that maps to a particular moderator M1, M2, M3, or M4, looking for that arrow in Figure 2, and coming up with a hypothesis linking the components in the two ends of the arrow with the variable I chose for the moderator.

In Table 5 below, I provide a few examples of hypotheses including specific moderating variables, that can be derived from the unified model (Table 4, Figure 2 and Figure 15). For example, the first three hypotheses are based on the proposition that moderating variables consisting of environment, task, person and need variables (M1) affect the relationship between information need and the decision to seek or search. Examples of other hypotheses in the table are derived from other moderating variables of the unified model.

| From M1 |

|

| From M1, M2 and M3 |

|

| From M4 |

|

These hypotheses may not be unique, and could be derived from past models. This is because the unified model does not seek to propose a new model, but to synthesise and reconcile past models. The hypotheses listed in Table 5 above (and others that can be derived from the unified model) can provide a direction for the design of new studies in information behaviour, and would be especially useful for doctoral students and other new researchers; e.g., the hypotheses in Agarwal, Xu and Poo (2011) and other empirical studies in information behaviour could easily have emerged from the unified model. See Agarwal (2018, pp.109-113) for a discussion on how research studies incorporating context can be designed.

Limitations

While this study has sought to address the limitations of prior integration efforts by also unifying integrated models, any such work, by its nature, has to be a work in progress, as it is an attempt to bind a moving field. The study has a number of limitations.

First, the unified model is a process model, i.e. it consists of a series of steps in a specific sequence. This follows many information seeking models, such as those by Wilson. However, this is not representative of all models we reviewed. For example, Dervin and Foreman-Wernet (2012), McKenzie (2003) and Lakshminarayanan (2010) do not prescribe any set sequence or process. Lakshminarayanan (2010) writes about this non-adherence to order and how “information processes can take short-cuts between the stages, backtrack, bypass some stages, or abandon information seeking” (pp.307-308).

Second, the study has focused on information seeking, and only incorporated a few general information behaviour models. There are other information behaviour models (e.g. on information avoidance) which could not be incorporated in this study. While I include use or give up in my model, I do not focus on information use studies.

Third, an argument could be made against the selection of all the varied models included in the paper. While the more exhaustive set that was included was perhaps more representative, a restricted selection might have facilitated a deeper analysis.

Fourth, one could argue that the proposed unified model is too general and does not contribute to our understanding of theories on information seeking. One could also question the content of categories derived from previous models in the unified model. The attempt in this paper can be understood as coming up with a variant theory, or theory variation, as per Wagner and Berger (1985). “By constructing variants, the theorist is able to make close comparisons of subtle differences in his or her thinking. Resolution of these differences can occur relatively quickly.” (p.56).

Fifth, as mentioned earlier, the study has focused on the individual seeker, not on collaboration. The unified model does not capture the fact that information sharing occurs at all parts of the collaborative process, not only after information is found.

Sixth, except for communication (Robson and Robinson, 2013), the model has not explored relationships with other fields outside information science.

Seventh, while the unified model (Figure 2) looks simple, in reality, it needs to be combined with Table 4 to be understood completely. When this happens, the model loses some of its simplicity.

Next, the study is a theoretical exercise, and like all theoretical studies, it brings in the biases and the subjective viewpoints of the author. This included choices made in reconciling metatheoretical assumptions when components were taken out of the context of their original models and incorporated into the unified model.

Finally, it could be argued that the unified model resembles current models, while not producing a new concept per se. The purpose of the study was not to introduce a new variable or a concept, but rather to try and synthesise the work done so far by unifying the various models that have been produced. Even as we arrive at new concepts and models, it is important to be familiar with the prior work done, so one can see what work remains to be done. In the abundance of models and frameworks in our field, this process of synthesis in a single paper is very useful for new researchers to quickly get up to speed on the prior developments in the field, and how these relate with each other.

Conclusions and future work

I have presented a unified model synthesising notable models of information seeking, as well as past integration efforts, thereby contributing to the process of synthesis and convergence that is needed in our field. I have concatenated different concepts from various models into a small unified set of concepts. The unified model will help system designers view user needs, context, and their information seeking behaviour as central to building context-aware systems.

This process of synthesis and unification should be an area for future work to focus on: to what extent are these equivalences accurate? Can any parts of the unified model be broken down further? What exactly are the relationships between concepts that I have put under the same umbrella? For example, how could all the modes, stages, strategies, emotions, and cognitive activities grouped under seeking and searching in the unified model be expanded into their own sub-model? (Bates (2002) works toward this same goal.)

After presenting the unified model, I also realise that this work is only one step toward the goal of understanding completely the relationships among people, information, and information sources and systems. For example, what would the unified model look like if I also included system-centred information retrieval models, in addition to the user-centred information seeking models included in the study? Over the years, there have been calls for collaboration between information seeking and retrieval, and a growing realisation that information retrieval research needs extension toward context, and information seeking towards task and technology (Järvelin and Ingwersen, 2004; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Kuhlthau, 2005). Ellis et al. (1999) found that scholars do not cite across the overlapping areas of information systems, information retrieval and user studies. Yet it has been often accepted that information needs and seeking processes depend on user’s tasks (Mick et al., 1980; Belkin et al., 1982; Ingwersen, 1992; Byström and Järvelin, 1995). Kuhlthau (2005) has called for synthesis of the insights of user studies and the innovations of information retrieval and information systems. Pettigrew, Fidel, and Bruce (2001) call for “a theoretical core complete with common assumptions and definitions and improved predictive value” (p. 44). During his acceptance speech for the Award of Merit at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Association for Information Science & Technology in Copenhagen, Peter Ingwersen said,

Redundancy and the ranking principle for information retrieval have become mainstream in research and commercial retrieval environments... IR implementation [is largely technological in nature]...it is not yet really user and context-driven. There’s much less focus on why and how information retrieval models actually do or do not work and how and why some work better than others e.g., in connection with interaction (Agarwal, 2016, 0:24 – 1:38).

Thus, incorporation of information retrieval models to the unified model would be a logical next step of this study. Similarly, the unified model could be expanded to communication studies, as Dervin has done in her work (see Dervin and Foreman-Wernet with Lauterbach, 2003) and as Wilson (2016) suggests, where he revises his model by including audience and output to apply it to the field of communication.

Future work should continue the process of synthesis by incorporating all facets of information behaviour, such as serendipity (see, e.g., Wilson’s expansion of his model in Wilson, 2020 to including accidental discovery), information avoidance, and information use; exploring relationships between information behaviour and related disciplines; unifying models of information retrieval and human-computer interaction; and finally creating a model that bridges the gap between user and system. It is hoped that such a model will lead to improved information services and systems and a better user experience.

The process of synthesising demonstrated in this study could be extended to take the work of a particular theorist and map the work of other theorists to it (for example, as done by Savolainen, 2017; González-Teruel and Abad-García, 2018; and Gonzalez-Teruel and Pérez-Pulido, 2020). That is, what would happen if we made Dervin, Wilson, or Belkin dominant and nested everything else inside the chosen theorist’s work? While it may not be possible to map all aspects of all extant models and theories to a particular work, there are areas where it is possible. This is what makes it important. I invite other researchers to join in this process of synthesising.

As Brenda Dervin wrote in her review of an initial version of this manuscript, where she identified herself as the reviewer, “offering your integration as the kind of writing and thinking we desperately need….open up the IB/ISU/IR (information behaviour / information seeking and use / information retrieval) communities to pursuing the kind of work you have started here – genuine synthesis and engagement rather than pastiching, shallow reading, and run on for a new hustle….We do have too many models and not enough thought.” Dervin further described the manuscript as, “…the methodological move (in the Weberian sense) that I think your article in its best interpretation is – not another model but a methodological move for better analysis.” Dervin, from what I understand, was alluding to Max Weber, a key proponent of research studies through interpretative rather than positivist methods. While this paper presents a unified model, the process of arriving at the model and comparison with other models documented in it can be seen as a methodology in itself.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my Ph.D. advisor, Danny Poo, for all his guidance during my Ph.D. years from 2005-2009, during which period, I started the initial work and first manuscript of this paper. I am also grateful to my student research assistant Alison Fisher, who worked with me in 2016-2017 in helping further thinking and updates on the paper since the initial work. The paper underwent more revisions and updates since then. Most of all, I’m grateful to Brenda Dervin for her feedback on the initial versions of this manuscript. With more than 15 years in the making, and multiple revisions over the years, this paper is an example of “the struggle involved in getting published – one has to interrupt a dominant discourse just enough but not too much…the struggle to stay in line and the struggle to fall out of line.” (Dervin, in her 2006 review, where she identified herself as the reviewer: “I used Dervin above as my example because, of course, as you may guess I am Dervin.”).

About the author

Naresh Kumar Agarwal is an Associate Professor and Director of the Information Science and Technology Concentration at the School of Library and Information Science, Simmons University, 300 The Fenway, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. He received his Bachelor's of Applied Science (Computer Engineering) from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore and his PhD from the National University of Singapore. He can be contacted at: agarwal@simmons.edu and nareshagarwal.com]

References

Note: A link from the title, or from "(Internet Archive)", is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Agarwal, N.K. (2018). Exploring context in information behavior: seeker, situation, surroundings, and shared identities. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services 9(7), 1-163. https://doi.org/10.2200/S00807ED1V01Y201710ICR061

- Agarwal, N.K. [@nareshag]. (2016, October 18). Prof. Peter Ingwersen sharing his thoughts on research directions during his Award of Merit acceptance speech #ASIST2016 [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/nareshag/status/788495573821321217

- Agarwal, N.K., & Alsaeedi, F. (2021). Creation, dissemination, mitigation: towards a disinformation behavior framework and model. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 73(5), 639-658. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2021-0034

- Agarwal, N.K., & Lu, W. (2020). Response to non-response: How people react when their smartphone messages and calls are ignored. In Proceedings of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 57, paper e260. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.260

- Agarwal, N.K. (2012). Making sense of sense-making: tracing the history and development of Dervin's sense-making methodology. In T. Carbo & T.B. Hahn (Eds.). International perspectives on the history of information science & technology: Proceedings of the ASIS&T 2012 Pre-Conference on the History of ASIS&T and Information Science and Technology. (pp. 61-73). Information Today.

- Agarwal, N.K. (2015). Towards a definition of serendipity in information behaviour. Information Research, 20(3), paper 675. http://informationr.net/ir/20-3/paper675.html. (Internet Archive)

- Agarwal, N.K., Xu, Y.C., & Poo, D.C.C. (2009). Delineating the boundary of ‘context’ in information behavior: towards a contextual identity framework. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 46(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.2009.1450460252

- Agarwal, N.K., Xu, Y.C., & Poo, D.C.C. (2011). A context-based investigation into source use by information seekers. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 62(6), 1087-1104. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21513

- Bates, M.J. (1990). Where should the person stop and information search interface start? Information Processing and Management, 26(5), 575–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(90)90103-9

- Bates, M.J. (2002). Toward an integrated model of information seeking and searching. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 3, 1-15. https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/info_SeekSearch-i-030329.html. (Internet Archive)

- Belkin, N.J. (1980). Anomalous states of knowledge as a basis for information retrieval. Canadian Journal of Information Science, 5, 133-143. http://faculty.washington.edu/harryb/courses/INFO310/Belkin1980_ASK.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Belkin, N.J. (1984). Cognitive models and information transfer. Social Science Information Studies, 4(2-3), 111-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-6236(84)90070-X

- Belkin, N.J. (1990). The cognitive viewpoint in information science. Journal of Information Science, 16(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F016555159001600104

- Belkin, N.J., Oddy, R., & Brooks, H. (1982). ASK for information retrieval. Journal of Documentation, 38(2), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026722

- Berger, J., & Zelditch, M. (1993). Theoretical research programs: studies in the growth of theory. Stanford University Press.

- Berger, J., Willer, D., & Zelditch, M. (2005). Theory programs and theoretical problems. Sociological Theory, 23(2), 127-155. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.0735-2751.2005.00247.x

- Borlund, P., & Ingwersen, P. (1997). The development of a method for the evaluation of interactive information retrieval systems. Journal of Documentation, 53(3), 225-250. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007198

- Brookes, B.C. (1977). The developing cognitive viewpoint in information science. In M. De Mey (Ed.), International workshop on the cognitive viewpoint (pp.195-203). University of Ghent.

- Buckland, M.K. (1991). Information as thing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 351-360. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199106)42:5%3C351::AID-ASI5%3E3.0.CO;2-3

- Byström, K., & Hansen, P. (2005). Conceptual framework for tasks in information studies. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 56(10), 1050-1061. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20197

- Byström, K., & Järvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information seeking and use. Information Processing and Management, 31(2), 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(95)80035-R

- Case, D.O. (2012) Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (3rd. ed.). Emerald.

- Case, D.O., & Given, L.M. (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (4th. ed.). Emerald.

- Chatman, E.A. (1996). The impoverished life-world of outsiders. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 47(3), 193-206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199603)47:3%3C193::AID-ASI3%3E3.0.CO;2-T

- Choo, C.W., Detlor, B., & Turnbull, D. (2000). Information seeking on the web: an integrated model of browsing and searching. First Monday, 5(2), https://firstmonday.org/article/view/729/638. (Internet Archive)

- Choo, C., & Auster, E. (1993). Environmental scanning: acquisition and use of information by managers. In M. Williams (Ed.), Annual review of information science and technology (pp. 279-314). Learned Information.

- Cole, C. (2012). Information need: a theory connecting information search to knowledge formation. Information Today, Inc.

- Cole, C. (2018). The consciousness’ drive. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92457-1

- Croft, W. B. (1987). Approaches to intelligent information retrieval. Information Processing and Management, 23(4), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(87)90016-1

- Cuadra, C. A., & Katter, R. V. (1967). Opening the black box of relevance. Journal of Documentation, 23(4), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026436

- D’Ambra, J., & Wilson, C. S. (2004). Use of the World Wide Web for international travel: integrating the construct of uncertainty in information seeking and the Task-Technology Fit (TTF) model. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 731-742. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20017