Free for all, or free-for-all? A content analysis of Australian university open access policies

Simon Wakeling, Danny Kingsley, Hamid R. Jamali, Mary Anne Kennan and Maryam Sarrafzadeh

Introduction. The purpose of this paper is to understand the characteristics of Australian institutional open access policies and to explore the extent they represent a coherent and unified approach to delivering and promoting open access in Australia.

Method. Open access policies were located using a systematic search of forty-two Australian university Websites. A formal open access policy was defined as a document with the terms "open access" and "policy" in the title, and which was located either in the institution’s policy library, or elsewhere on the main university Website.

Analysis. Content analysis was employed to examine policies across fourteen categories.

Results. Only twenty Australian universities were found to have a formal open access policy. There was found to be a wide variation in language used, expressed intent of the policy and expectations of researchers. Few policies mentioned monitoring or compliance.

Conclusions. When policies use language which does not reflect national and international understandings, and when requirements are not clear and with consequences, policies are unlikely to contribute to understanding of open access, to uptake of the policy, or to ease of transferring understanding and practices between institutions. A more unified institutional approach to open access is recommended.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper933

Introduction

In the context of scholarly communication, open access (OA) refers to the principle that research outputs should be freely and openly available for all users in a form which is "digital, online, free of charge, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions" (Suber, 2012, p. 14). open access has been shown to have significant and tangible social and economic benefits (Tennant et al., 2016). Ensuring that access to published research outputs is equitable and cost effective is an important challenge for the higher education sector, and for Australian society at large (CAUL and AOASG, 2019).

Since the earliest days of the open access movement, as evidenced in the declaration of the Budapest Open Access Initiative (2002), two routes to open access have been proposed, now commonly referred to as Green and Gold. Green OA refers to the practice of depositing versions of research outputs into institutional or other repositories, thereby making their content available to all potential readers even if the articles are formally published in subscription journals. Gold OA refers to models by which the article itself is published in open access form by the publisher. This includes both open access journals (i.e., journals for which all content is available without subscription or other fees), and instances where subscription journals publish some articles in open access form, charging authors an article processing charge (APC). This latter model is sometimes referred to as Hybrid open access. While intended to support the same broad aim (making research outputs freely available to all) Green and Gold models are distinct. Green OA requires sophisticated repository infrastructure and policy formulation to incentivise and support author depositing of articles. Gold OA, meanwhile, has required the development of new publishing practices, including funding models such as APCs to finance open access journals, and the addressing of challenges relating to deep-rooted researcher practices and incentives related to journal selection.

The open access landscape is therefore complex and multi-faceted. As Pinfield et al. (2020) have shown, multiple dimensions operating at different levels involve many different actors combining in intricate ways. Advancing open access performance therefore requires the formulation and implementation of a range of strategies and processes carefully designed to address behavioural, technical, and cultural issues. To take the example of just one geographic region, Europe, the last ten years have seen a huge range of projects and policy initiatives designed to promote the uptake of open access publishing rates. The European Commission (2016) published their Guidelines on Open Access to Scientific Publications and Research Data in Horizon 2020 in 2016, and the associated Horizon 2020 programme represented a EUR30 billion investment in research and innovation between 2018-2020, under which 'each beneficiary must ensure open access to all peer-reviewed scientific publications relating to its results' (European Commission, n.d.a). More recently, Plan S has been launched (cOAlition S, 2021), a far reaching and somewhat controversial initiative designed to ensure that the outputs of publicly funded research be made available in open access form.

These national and supranational policies and frameworks are complemented by institutional polices. Recent research has shown that the European higher education sector has a sophisticated approach to institutional policy development and implementation, with 91% of institutions either having or developing an Open Science policy, a notable figure, given that such policies go beyond the boundaries of open access specifically, and embrace the broader concept of open science (Morais et al., 2021). The overall effect has been striking, with European countries in leading positions in rankings of global open access performance (European Commission, n.d.b).

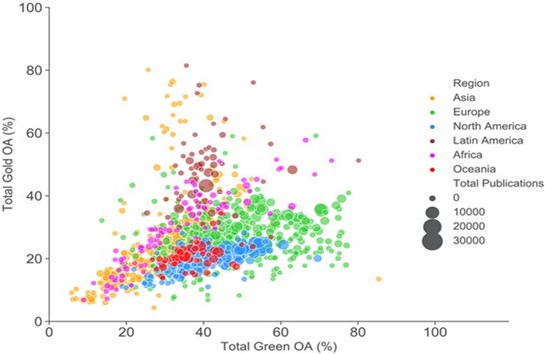

In contrast, Australia is now lagging behind, and there are urgent calls for open scholarship to be a national priority (CAUL and AOASG, 2019; Foley, 2021). Recent research evaluating international open access performance levels has shown that "universities in Oceania … lag behind comparators in Europe and Latin America" (Huang et al., 2020); see Figure 1. There is also increasing awareness that policies, and particularly open access mandates, are a crucial means of driving up open access adoption levels (Larivière and Sugimoto, 2018). In contrast to many other countries there is no overarching open access position in Australia. While major national funders such as the Australian Research Council (ARC) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) have policies requiring research to be made available as open access, more than 30% of outputs from such funded projects fail to comply with this mandate (Kirkman and Haddow, 2020), and indeed these funders represent only 14.6% of all higher education research and development funds (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). The major source of research and experimental development funding in Australian higher education organisations is general university, or institutional, funding (56%), and such funds are not subject to national funder open access mandates (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

The Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research requires universities to develop and maintain 'policies and mechanisms that guide and foster the responsible publication and dissemination of research' (Australian Government, 2018, p. 2). Since there is also a requirement that 'institutions should support researchers to ensure their research outputs are openly accessible in an institutional or other online repository, or on a publisher’s website' (p. 3), it seems clear that institutional open access policies have an important role to play in driving open access performance. However, regional comparisons published by the Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (COKI), which are dynamically updated over time (Figure 1), indicate that institutions in Oceania, where Australia is located, perform relatively poorly in terms of open access (for the dynamic graphic see Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative (2020) and Countries: open access over time).

It is possible that one reason for this relatively poor performance is that the policy framework at an Australian institutional level does not effectively enough encourage or support open access. While the responsibility for managing open access policies is placed with institutions, to the best of the authors’ knowledge to date there has not been a detailed analysis of open access policies in Australian universities. This study aims to provide a content analysis of the open access policy landscape in Australia, considering key aspects of open access policies, including the means by which open access is achieved; the timing of the deposit of work into a repository and whether this differs to the timing of when it is required to be made openly available; the provision or otherwise of funds to support open access publishing (and whether there are restrictions around these funds); and other aspects of the policies. The stated intention and purpose of the policies is also of interest.

In particular this project sought to answer the following research questions:

- What are the characteristics of Australian institutional open access policies, in terms of content, intent and compliance mechanisms?

- To what extent do Australian university open access policies represent a coherent, unified approach to delivering and promoting open access in Australia?

Literature review

There have been some prior efforts to identify open access policies at Australian universities. Kingsley (2011) noted that in 2011 seven Australian universities had open access mandates, but argued that several of these institutions were in fact 'encouraging' rather than mandating open access. A later analysis found that as of January 2013, nine universities either had, or were in the process of implementing, open access mandates (Kingsley, 2013). Callan (2014) identified twelve institutions with open access policies in her review of the Australian open access landscape.

Previous studies have reported individual institutions’ experiences of developing and implementing open access policies, both in Australia and internationally (Cochrane and Callan, 2007; Hoops and McLaughlin, 2020; Kern and Wishnetsky, 2014; Kipphut-Smith, 2014; Orzech and Myers, 2020; Otto and Mullen, 2019; Saarti et al., 2020; Soper, 2017). These case studies typically provide detailed accounts of challenges and opportunities associated with open access policy design. Across this literature several key themes emerge, including the different but significant roles played by the library in open access policy development, and the range and complexity of associated systems and processes required to support implementation. It is also clear that there is a need for policy to be developed in consultation with researchers, and a requirement for ongoing advocacy work to obtain buy-in from research staff. This literature also reveals key differences in open access policy design, including whether policies take an opt-in or opt-out approach, and whether depositing work in an institutional repository is mandatory or voluntary. In addition to these institutional studies, earlier work has also focused on the nature and impact of national and funder policies (Awre et al. 2016; Crowfoot, 2017; Huang et al. 2020; Kirkman and Haddow, 2020). These are relevant to our analysis of institutional policies in that they suggest significant levels of variation in the requirements of these policies, particularly regarding embargoes, and positions on Gold open access options. Overall, there is strong evidence that these policies have contributed to increased levels of open access performance.

Several recent publications relate to open access policy design, and highlight specific criteria that open access policies should include in order to maximise compliance and performance. Swan et al. (2015) note that the open access deposit of research outputs should be mandatory, that deposit waivers should not be supported, that the depositing of research outputs should be linked to research evaluation, and that a requirement for immediate deposit is preferable. Morrison et al. (2020) include recommendations for how institutions can 'support their authors in maximising their research reach and impact by enabling OA' (p. 36). As well as suggesting that institutions provide support and guidance to researchers on copyright and licensing issues, the report notes that research institutions should 'work with publishers, funders and open access advocacy bodies to adopt standardised language when describing policy positions on copyright ownership and licensing' (p. 34) and 'ensure standardised language is used by research offices, university libraries and academic schools when advising academic authors on open access copyright retention and reuse licence' (p. 36). Larivière and Sugimoto (2018) note that allowing authors to deposit research after publication leads to lower deposit rates, and that the most effective policies are those with established and effective enforcement processes, and proper supporting infrastructure.

Most relevant to this study are the small number of publications that report surveys of institutional open access policies. While no such work appears to have been conducted in Australia, there are several international examples. Bosman et al. (2021) present a multidimensional framework incorporating different aspects of open access (for example what research outputs are covered by policies, how and when open access should be delivered, copyright issues), the different actors involved, and the levels of support encompassed by the policies. The authors review institutional, national and funder open access policies affecting Dutch researchers and note whether these policies meet the various criteria outlined in the framework. The analysis provides important insights into the broader open access landscape, but seeks to illustrate the utility of the framework rather than undertake a granular content-based comparative analysis of the policies under review. Boufarss and Laakso (2020) surveyed research administrators in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which included questions relating to institutional open access policies. Only 7% of institutions were found to have a policy, with more than half stating that they had no plans to develop one. Encouraging self-archiving and raising awareness of open access were the most commonly stated purposes of the policies.

Two studies merit more detailed discussion, as they relate closely to our study, and provide various points of comparison to our analysis of Australian open access policy. Fruin and Sutton (2016) report the results of a questionnaire relating to open access policies at US institutions. The questionnaire explored the rationale, processes and content of the institutions’ policies, and was directed only at institutions which had implemented, were in the process of implementing, or had attempted but failed to implement an open access policy. The study also explored the incorporation of waivers in policies, the role of libraries in driving and managing policies, the arguments used to support open access in principle, and whether publisher embargoes are respected.

Hunt and Picarra (2016) examined European open access policy alignment based on an analysis of ROARMAP (Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies, an international registry of self-reported open access policies), European funder policies and 365 institutional policies. They found that 63% of institutional policies mandated the deposit of research items, with 96% specifying a repository as the locus of deposit. However, only 38% of institutional policies were found to include a requirement to make that deposit open access. The study also compared timeframes for making research outputs open access. A key finding of this study was that a significant number of institutional policies "do not specify or mention some essential elements which are critical to promoting a strong, effective policy" (p. 4), particularly relating to the time period for making outputs open access, length of embargo periods, Gold OA publishing options, and a clear link to research evaluation.

From the early days of open access to more recent times, the literature asserts how the various actions of government, funders and institutions (such as providing finance and supporting infrastructure, recognising and rewarding, legalising and promoting, setting as setting policy and stating as a goal), are interrelated and reinforce each other in the uptake of open access. In this paper we analyse the content and intent of Australian institutional open access policies, as a means of better understanding how they might contribute (or otherwise) to the uptake of open access in Australia.

Method

The study applied a content analysis approach. This approach was deemed the most effective way of addressing our research questions because it provides a structured technique for identifying and comparatively analysing the content of documents (Payne and Payne, 2004); here, institutional open access policies. The method required three distinct phases: identifying relevant Australian institutions, collating and categorising documents for these institutions, and undertaking the content analysis itself.

Identifying Australian institutions

To identify institutions we used the Australian Government's List of Australian Universities that includes forty-two universities (Study Australia, 2022). We initially consulted the Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies (ROARMAP) to identify which of the institutions have formal open access policies. However, it became apparent that whilst a useful resource, ROARMAP does not contain up to date information for some institutions. We therefore conducted our own systematic search of institutional Websites to identify policies. This process first involved searching university Websites to locate their policy libraries. Within the policy libraries, further searches were conducted using the keywords:

- Open access

- Publication

- Authorship

- Research

- Dissemination

- Theses

- Intellectual property

The policies, procedures or guidelines that were found were reviewed, and those relevant to open access were downloaded and saved. Where institutions’ policy libraries did not appear to have any policies, procedures or guidelines that referred to open access, and for institutions without a searchable policy library, the university Website was searched using the term open access to identify any other relevant documentation. Appendix 1 lists the universities included in the study, and shows abbreviations used within the article.

Categorising documents

The resulting documentation was reviewed, and subjected to an initial classification of policy scope. A key question that informed this analysis was how to define a policy. The language used in policy development is very specific. Terms such as policies, procedures, guidelines and others have particular meanings, and these are articulated in some instances (University of Queensland, 2020). For the purposes of this study, we defined a formal open access policy as a document with the terms open access and policy in the title, and which was located either in the institution’s policy library, or elsewhere on the main university Website. A second category consisted of institutions with policies that mention or relate to open access as part of a document with a broader scope (e.g., Research publication policy, Research repository policy). The third category consisted of institutions without a formal open access policy, but which provided less formal open access guidelines, principles or procedures document. These documents were sometimes published on LibGuide sites. The final category related to institutions without any policy, formal or informal, relating to open access. Carnegie Mellon University was excluded from the study at this point, because the relevant policies were found to originate from the US parent institution, rather than be developed in Australia. This left forty-one universities.

This process resulted in identification of twenty (48.8%) universities which have a formal open access policy (Table 1). Eleven (26.8%) institutions were found not to have open access policies, but to have other policies that reference open access, while two (4.9%) universities without formal open access policies have other open access-specific documents titled principles, procedures or guidelines. Eight universities (19.5%) were found to have no policies, procedures or guidelines related to open access.

| Open access policy status | No. of universities |

|---|---|

| Institutions with open access policies | 20 (48.8%) |

| Institutions without open access policies, but with other policies that reference open access | 11 (26.8%) |

| Institutions without open access policies but with open access principles, procedures, or guidelines | 2 (4.9%) |

| Institutions that have no policies, procedures, or guidelines referencing open access | 8 (19.5%) |

Undertaking the content analysis

We focused our analysis on the twenty formal open access policies identified during the initial classification process. Including other types of policy that mention open access, or non-formal open access policy documents, would have made the analysis impractically complex, and would have required comparing documents with very different purposes and scope. All formal open access policies were downloaded between November 2020 and January 2021 and subjected to analysis using a mix of checklist and content analysis. We note here that some institutions may have updated existing policies, or introduced new ones, since the data were collected, and therefore the results are indicative of the open access landscape at the time the research was conducted. In selecting which aspects of the Australian policies to analyse, ROARMAP data categories were consulted along with some literature (Awre et al., 2016; Bosman et al. 2021).

The categories used in the various analyses were different in each context and used different language to describe similar concepts. We borrowed categories for analysis from these previous studies and sites, then combined and/or added categories, labelling them in ways that seemed relevant to the Australian context and where possible using language reflected in the policies. This process involved all the research team and much discussion and refinement of categories. For example, for what we categorise as output types included in the policy, ROARMAP refers to as content types specified, Bosman et al. (2021) refer to as What is made open access, and Awre et al. (2016) as A description of the type of research output which the policy covers. Following this process each document was examined for information in the following categories:

- Date of first version of the policy

- Date of most recent version of the policy

- Date of next scheduled review of the policy

- Responsible office/Policy owner

- Definition of open access

- To whom the policy applies

- Output types included in the policy

- Timing for depositing outputs

- Role of the library

- The language used to describe responsibilities

- Exceptions to the policy

- Consequence for non-compliance

- Intent of the policy

- If and how funding for paying Article Processing Charges is covered in the policy

The categories were developed inductively by the researchers and were discussed and refined by the research team. The information collected for each policy was checked by at least two researchers to ensure its accuracy. All information and coding were recorded in a spreadsheet that is publicly available here.

Analysis of the intent of the policies was more complex. Each policy was scanned for language that referred to the purpose of the policy, and any information that referenced a position on how to approach open access. This text was extracted into a separate table and analysed for any terms that were repeated or distinct. This identified different approaches from institutions such as recommending the use of an author’s addendum, or that authors retain the copyright of their work. A related analysis considered the specific language around the benefit of the policy which fell into clear categories including the benefit to society, increasing access to research, and maximising the research impact.

Findings and analysis

In presenting our findings and analysis, we distinguish between findings related to a descriptive analysis of the policies (i.e., the number and date of policies, to whom policies apply, ownership of policies and the role of the library, mentions of funders in open access policies, exceptions found in policies, timing of deposit, and consequences for non-compliance) and more conceptual analysis of dimensions of policies relating to language and intent.

Descriptive analysis

Number and date of policies

As noted above, twenty out of forty-one Australian universities were found to have active open access policies. This represents an increase on the eleven institutions found to have policies in 2013 (Kingsley, 2013). In our study, where the date of the first version of these policies was reported (n=19), the oldest policy was from 2003, and the second oldest from 2008. The years 2013 and 2014 were clearly a key time for policy creation as ten policies were implemented during this period. Three policies were created in 2020. The median age of the policies was seven years (created in 2014). However, we must acknowledge the possibility that some institutions may have had older policies that were subsequently superseded, and so were not included in our analysis. Analysis of the Date of next scheduled review of the policy data shows that of the nineteen policies with a stated review date, ten show a historic date, with eight of these being pre-2020.

To whom the policy applies

Variation was found in defining the people to whom the policies apply. In some cases, definitions were detailed and granular: "This policy applies to all staff (including conjoint and adjunct staff) and students undertaking research at UNSW, either full-time or part-time and applies to scholarly research outputs" (UNSW). Others were more general: "This policy applies across the University" (ANU). Such statements were analysed and categorized into four groups: staff, students, affiliates, and contractors. Table 2 shows that all open access policies were found to apply to staff, and the vast majority to students and affiliates.

| Categories | No. of open access policies |

|---|---|

| Staff | 20 (100%) |

| Students | 18 (90%) |

| Affiliates | 15 (75%) |

| Contractors | 1 (5%) |

Ownership of the open access policies

As might be expected, each policy named a person or persons with responsibility for the policy. There was a surprising lack of consistency in the terminology used to describe these individuals and groups, reflective perhaps of different governance and organisational structures and associated nomenclature across Australian universities. Common titles were Accountable Officer; Administrator; Approval authority; Contact officer; Governing authority; Policy Custodian; Policy owner; Policy sponsor; Reference Authority; and Responsible officer. Each policy was found to mention at least one of these terms; some mentioned more than one. For example, the Australian Catholic University policy names an Approval authority, Governing Authority, and Responsible Officer.

In thirteen policies (65%), a position in the library was identified as responsible for the policy. In most cases the Library Director or University Librarian was named. Eight policies identified a non-Library contact as the person responsible for the policy; these most often were pro or deputy vice-chancellors. These results are broadly consistent with Fruin and Sutton’s findings relating to US open access policies (2016), which found that open access policies were library led in the 'vast majority' of cases.

Role of the library in open access policies

Five open access policies (25%) did not mention the library. For the remaining fifteen, the role of the library was most often related to the institutional repository, delivering assistance or advice, and supporting copyright compliance (Table 3). We note that Fruin and Sutton’s study of US institutional open access policies found that while university libraries typically played a major role in open access policy development, implementation and support, these roles were often not articulated in the policies themselves. It is therefore possible that our results are not truly representative of the library involvement with open access activities.

| Library role | No. of policies |

|---|---|

| Repository | 10 (50%) |

| Assistance/Help/Advice | 9 (45%) |

| Copyright compliance | 8 (40%) |

| Reporting | 2 (10%) |

References to funders in open access policies

References to funders were found in all twenty policies. Analysis reveals significant differences in the relationships between funder and institutional open access policies (Table 4).

| Type of reference | No. of policies |

|---|---|

| Policy states that it complies with requirements of ARC/NHMRC open access policies | 8 (40%) |

| Policy states that it "supports" ARC/NHMRC policies | 4 (20%) |

| Policy states that researchers must comply with ARC/NHMRC policies | 5 (25%) |

| Policy states that it is based on ARC/NHMRC open access policies | 2 (10%) |

| Policy states that it will facilitate reporting on ARC/NHMRC policy compliance | 1 (5%) |

While one policy mentions funders only in the context of the policy being a tool to facilitate reporting and monitoring of compliance with funder policies, all the other policies incorporate funder open access policies is a substantial way. Funders were found to be most often mentioned in the context of institutions stating that their policies comply with funder requirements. The implication here is that institutional policies have been designed to ensure alignment with minimum funder requirements, such that researchers acting in accordance with the institutional policy will automatically comply with Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council policies. In addition, two policies (Queensland University of Technology) and the University of Queensland) while not specifically mentioning compliance, explicitly state that they are based on the requirements of Research Council and Medical Research Council policies. In contrast, five policies include specific requirements for authors to comply with national funder open access policies, in addition to the requirements outlined elsewhere in the policies, implying that adhering to the standard policy requirements alone would not ensure compliance with funder policies. In the remaining four cases, policies are less clear about the relationship between institutional and funder policies, stating only that they support funder policies, and including no specific requirements to adhere to funder policies.

As noted above, the major Australian national research funders (the Research Council and Medical Research Council) represent only 14.6% of all higher education research and development funds (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Nonetheless, their open access policies have clearly had a strong influence on institutional open access policy development. This in turn suggests that stronger funder policies will result in stronger institutional policies, and improved open access performance nationally. This is supported by evidence from recent literature which has highlighted the effects of funder policies on national open access performance levels in countries such as the US, UK, Canada and the Netherlands (Larivière and Sugimoto, 2018; Huang et al., 2020; Robinson-Garcia et al., 2020).

Exceptions

All twenty open access policies specified various exceptions to the standard requirement that work be made available open access (Table 5). It should be noted that the category creation was driven by the language used in the policy. It could be argued, for example, that Publisher agreement and Copyright or licensing restrictions are closely related, but it was thought important to note the difference in language used in the policies. In practice this distinction typically referred to the difference between publisher embargo periods and other restrictions. For example:

Where deposit of the full-text material, or dataset, is not possible due to publisher embargo, or is not permissible due to copyright or licensing restrictions. (Bond University)

Other exceptions included concerns related to commercial or cultural sensitivity, and confidentiality, although less than half of all open access policies specified these exceptions.

| Exception type | No. of policies |

|---|---|

| Publisher agreement (including embargo) | 18 (90%) |

| Copyright or licensing restrictions | 8 (40%) |

| Commercial sensitivity | 6 (30%) |

| Confidentiality | 6 (30%) |

| Cultural sensitivity | 3 (15%) |

| Legal obligations | 2 (10%) |

| Already open access material | 1 (5%) |

| Publisher version of non-open access publications (i.e., version of record) | 1 (5%) |

| Royalty payment or revenue | 1 (5%) |

It is instructive to consider these findings in the light of previous studies. Fruin and Sutton’s study of US open access policies (2016) found that just 10% of institutional policies specified not observing publisher embargoes, with most policies incorporating waivers for authors, both results broadly consistent with our findings. Similar results were found in Hunt and Picarra’s study (2016), with 21% of institutional policies not supporting any waivers to open access deposit. It seems clear that there is a general trend for institutional open access policies to explicitly respect publishers’ positions on open access, thus not following Swan et al.’s (2015) recommendation that such policies should not allow waivers.

Timing of deposit

There is evidence that timing can make a difference to the compliance rate (Herrmannova et al., 2019). Only thirteen of the twenty open access policies specify a timeframe within the policy, and there were significant variations within these policies. The University of Melbourne and the University of Wollongong specified the period of time within which the work should be deposited into the repository (within three months of publication and at the time of publication respectively). Australian National University has different requirements for deposit to the repository depending on the item in question, but for journal and conference publications, technical reports and other original, substantial works, the timing is: 'within 3 months or as promptly as possible after publication'. Four universities specify deposit upon or after acceptance for publication: Edith Cowan University, Macquarie University, Queensland University of Technology, and Australian Catholic University. Publisher embargoes relate to a period of time after publication, so institutions requiring deposit prior to publication must have systems in place to revisit these works at the time of publication to set the embargo. As Larivière and Sugimoto (2018) have noted, it is essential that open access policies are supported by proper technical infrastructure and process design, for example, to switch embargoed deposits to open once embargo periods are over.

The distinction between when something is deposited and when it is made openly available means in some instances a deposited item might not be made openly available for up to 24 months after deposit. For this reason, it is significant if a policy does stipulate when a work should be openly available, as distinct from when a work should be deposited. One example is the University of Adelaide which states: 'Researchers are encouraged to avoid embargoes of greater than 12 months from date of publication. Where agreements do not allow outputs to be made Open Access within 12 months researchers should make reasonable attempts to negotiate this provision with the publisher'. Other institutions are more vague (e.g., 'as soon as possible', Western Sydney University) or provide caveats to standard timeframes ('within twelve months of publication or as soon as possible').

This inconsistency and lack of clarity about what is actually required for deposit and openly accessible timeframes is a significant issue for a unified position and policy across the country. The variations in Australian institutional policies are consistent with findings from other studies, including Hunt and Picarra (2016), who found that 43% of European institutional policies failed to mention the timing of deposit, with most of the remainder using vague terms such as "when the publisher permits".

Compliance/consequences of breach of policy

Taken in isolation, the language associated with open access directives, as described above, might be considered relatively strong. It is important, however, to consider this language not only in terms of the associated exceptions to the policy, but also to the compliance and monitoring mechanisms associated with the policy, and the stated consequences of a failure to comply. We found that open access policies typically do not explain the monitoring processes. This is perhaps not surprising, because a detailed outline of such activity might reasonably be considered to be beyond the scope of a formal policy document. It is also important to recognise that the requirement to comply with university policies, and consequences of non-compliance, may be outlined in other formal documents (such as employment contracts and codes of conduct). It is notable, however, that only three of the twenty open access policies (15%) (Macquarie University, University of Adelaide and University of New England) specifically state the consequences of a failure to comply. In all three cases, the impact of the statement is softened by the inclusion of the word may, for example:

The University may commence applicable disciplinary procedures if a person to whom this policy applies breaches this policy (or any of its related procedures). (Macquarie University)

That so few policies were found to explicitly discuss compliance monitoring is consistent with the findings of Hunt and Picarra (2016), who argued that 'a significant number' of open access policies omit elements, including monitoring, and links to research assessment activities, that are 'critical to promoting strong, effective policy'. Crowfoot (2017) has noted the issues with compliance and monitoring in the context of funder policies, while Larivière and Sugimoto (2018) have argued that the best policies are those which are effectively enforced.

Conceptual analysis

Definitions of open access

As might be expected in a formal policy document, a very high proportion of university open access policies (90%) were found to include a definition of open access. It was expected that policy definitions would reflect commonly understood definitions. While the majority of policies had a definition of open access, very few of the definitions were the same. Definitions were shared only in two cases, each by two universities.

Shared understandings are more likely to make it easier to implement open access within and between universities, at national and international levels, and to build community acceptance and understanding of open access models. Faced with the challenge of drafting a definition of open access for inclusion in policies, we might expect authors to borrow from definitions found in well-known open access initiatives or related policies, such as the Budapest Open Access Initiative (2002), Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities (Berlin) (2003), or UNESCO (n.d.). Given the Australian context, we might also expect to see text based on the Australasian Open Access Strategy Group (2019 and based on the Budapest and Berlin declarations) or even the Australian Research Council (2021) and National Health and Medical Research Council (2018) definitions. Searches in Google and Google Scholar revealed that most definitions covered aspects from the above definitions, but only two policies referenced the sources of their definitions, one of these referencing the Austalasian Group (the Australian Catholic University) and one the Budapest Initiative (University of New South Wales).

The Research Council and Medical Research Council definitions cover reuse, licensing and attribution which are key concepts in understanding open access; however, most definitions used simplified language and some focused only on access, for example:

Open Access means immediate, permanent, unrestricted, free online access to the full-text of refereed research publications. (University of New England and James Cook University)

One made the definition local to their own organisation:

Open access means free and unrestricted (electronic) access to La Trobe University conducted research, articles and other scholarly outputs. (La Trobe University)

Another made the definition only relate to green open access in a repository and did not reflect other open access options:

Open Access means permanent, free online access to research and scholarly publications through a central repository on the public internet. (Southern Cross University)

These simplified definitions did not refer, for example, to reuse, licensing and attribution which are key concepts in understanding open access, misunderstandings of which may affect the likelihood of researchers to make their work open access (Zhu, 2017). While it is understandable that definitions are simplified for accessibility, definitions which do not reflect national and international understandings or miss important aspects of open access are unlikely to contribute to understanding of open access, to uptake of a policy, or to ease of transferring understanding and practices between institutions. It is also important to note Morrison et al.’s (2020) recommendation that successful open access policies should use standardized and consistent language both within and across universities.

Language used to describe the policy directive

Our content analysis also included identification of the language used in association with the open access directive. Table 6 presents the most commonly found words used in association with the instructions to researchers, along with examples of the terms in context. In many cases the language is strong (must, required), implying a mandate even if this particular word is not included. We also note a distinction between whether policies use an active ('researchers will...') or passive ('research outputs must be made...') form. Once again, the language used to describe the policy is varied, in contrast to the recommendation by Morrison et al. (2020)that policy language should be standardised across institutions. One might also question the extent to which the language used constitutes a mandate, as recommended by Swan et al. (2015). Notably only one policy was found to use the word.

| Key word | No. of policies | Example |

|---|---|---|

| must | 5 (25%) | 'fulltext research outputs must be made openly available where...' |

| will | 4 (20%) | 'Researchers will... make publications and data arising out of research openly available for re-use and citation'. |

| requires/required | 3 (15%) | 'The University requires all staff and students to deposit Research Outputs … for the purpose of providing Open Access' |

| responsible/responsibility | 3 (15%) | 'the following responsibilities are in place... Secure where possible the immediate unrestricted access to publication'/td> |

| is to be | 2 (10%) | 'material... is to be deposited in the University’s open access institutional repository' |

| mandates | 1 (5%) | 'The University mandates an open access approach...'' |

| should be | 1 (5%) | 'Research Outputs should be forwarded to the University Library for deposit into the institutional repository... if an open access version is not already available' |

| encourages | 1 (5%) | 'The University encourages staff and students to...' |

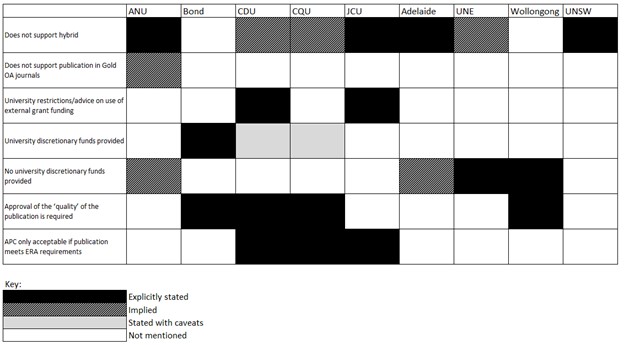

Payment for publication and hybrid journals

We examined the specific statements used within policies that relate to paying for open access publication and these are reported in Figure 2. Detail of the positions taken on the payment of article processing charges in subscription journals in particular (known as hybrid open access) are relevant, because charging authors a processing charge and readers a subscription for the same article has led to accusations of double dipping by these publishers (Phillips, 2020). A 2016 analysis of requirements of UK funders, and of US and UK library-run funds found there was a wide variety in the way the expectations regarding hybrid was expressed (Kingsley and Boyes, 2016). Given the Australian investment has historically focused on green open access (putting a copy of the work into repository), the assumption could be made that hybrid would be at odds with this strategy in Australia.

In fact, the variation found in the UK and US policies was reflected in our analysis of Australian open access policies. Some of the policies are indeed clear on the question of hybrid. For example, James Cook University says, "Hybrid Open Access publication is not supported by this policy." The Australian National University states it does not support hybrid, but the use of the word ‘or’ in the policy means it could be interpreted to say it does not support the payment of any article processing charges: 'The University does not support the payment of article processing fees (APCs) or ‘hybrid’ fees (where an individual article is made available through payment of an article processing fee)'.

Neither Bond University nor the University of Wollongong mention hybrid, but have opposing positions on paying for publication. Bond makes no restrictions or suggestions on paying for publication: while the University of Wollongong states: "The University maintains a position to not pay for the publishing of online research where possible." There are implied sanctions on hybrid in several policies that explicitly support Gold Open Access Journals and which do not specifically mention hybrid. For example, Charles Darwin University uses the expression: 'In a journal that is deemed to be Gold Open Access'.

Perhaps more than any other element of our analysis, the findings relating to positions on paying for publication illustrate the lack of a consensus vision for open access in Australia. Given Morrison et al.’s (2020) persuasive arguments for consistency and standardisation across institutions, and the complexities associated with different visions for open access, this represents a significant issue for the delivery of open access in Australia.

Intent of policies

Considering the text used within a policy that refers to the intent or rationale behind the policy, a series of perspectives arise (Table 7). We identified three main categories of motivation: to increase the profile of the research of the university, to ensure the university research has a wide audience, or because open research benefits society. As with other aspects of our analysis, there is a clear lack of consistency in the rationale used, with no single argument being adopted by more than half of the studied universities. Nine universities have a statement of intent within the policy which refers to a wider benefit beyond the institution. However, these vary considerably. The Australian Catholic University policy stands out because it is widely encompassing and quite specific in its stated purpose, referencing the Australian Deputy Vice Chancellors (Research) Committee mandated Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) Statement (Australian FAIR Access Working Group, 2022).

| Rationale | No. of policies |

|---|---|

| Open benefits society | 8 (40%) |

| Increases access to the university’s research | 7 (35%) |

| Maximises research impact | 6 (30%) |

| Infrastructure | 2 (10%) |

| Reproducibility | 2 (10%) |

The remaining policies that are classified within the open research benefits society vary in scope and aim. Some policies specifically refer to benefits to society, for example the University of Queensland policy aims to 'ensure the results of research are made available to the public, industry and researchers worldwide, for the benefit of society' and the University of New South Wales states that: 'Open Access publication enables us to share our capability in research and education effectively and equitably with global partners and stakeholders'. Others are more tangential in their reference to benefits, such as James Cook University which notes the policy is 'recognising that knowledge has the power to change lives'.

Others are more focused on exchange of information with the public. For example, the University of Sydney states the policy 'supports the University’s core values of engaged inquiry and mutual accountability'. Both Macquarie University and the Australian National University refer to the open exchange of information as a 'bedrock academic value'. Despite the general philosophy that publicly funded research should be publicly available, only Edith Cowan University and the University of New England specifically refer to 'publicly-funded research'.

Discussion

Prevalence and strength of Australian institutional open access policies

The Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research devolves responsibility to institutions to develop and maintain open access policies (Australian Government, 2018), but the results this study demonstrates that only twenty (48.7%) of universities have a formal open access policy. This finding is particularly concerning given the wealth of evidence from around the world that confirms the positive impact of strong and consistent open access policies (Herrmannova et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Larivière and Sugimoto, 2018; Rieck, 2019; Robinson-Garcia et al., 2020).

Funder mandates, institutional policies, grass-roots advocacy, and changing attitudes in the research community have contributed to the considerable growth in open access publishing during the last two decades (Huang, et al., 2020). While having an open access policy is important, the literature demonstrates that a policy alone is not enough to ensure the open access of research outputs. Clear language and processes for the enforcement of open access in policies is required to stimulate significant growth of open access. Our analysis found that none of the twenty existing Australian university open access policies mentioned monitoring of compliance, and only three specified any consequences for a failure to comply. While there may well be monitoring activities taking place at many Australian universities, it is clear that these are not widely publicised, and certainly not codified in policy documents. However, it has been shown that there is a clear link between compliance rates and clearly stated consequences for non-compliance (Larivière and Sugimoto, 2018). This evidence should provide strong incentive to policy makers at all levels, including Australian universities, to ensure that open access policies include meaningful consequences for compliance failures.

Standardisation, consistency, and aligned intent

Our analysis clearly demonstrates enormous variation across open access policies. We found significant differences in the intent of policies; the definitions of open access; the arguments used to support it; requirements for the timing of open access deposits; positions on paying for publication; the language used to describe researcher responsibilities; the exceptions to open access requirements; and the role of libraries in both policy development and compliance and monitoring. While we recognise that institutions are independent entities with their own goals and priorities, and therefore some variation is perhaps inevitable, the overall picture is one of confusion and inconsistency. This is especially troubling given that Australian researchers do not work in institutional vacuums. Cross-institutional collaboration is commonplace in Australia (Luo et al., 2018), as is researcher mobility, with most academics working at multiple universities over the course of their careers (Bexley et al., 2011).

Our analysis demonstrating the wide variety of positions on, and language about, open access in Australian institutional policies is likely to suggest to researchers that open access is a fractured concept. This may be a result of open access policies being developed and owned by a range of roles and institutional areas which may have different priorities and account for some of the lack of standardisation in the policies. While evidence has repeatedly shown that clear, consistent national or supranational positions on open access are the most effective way of maximising open access performance, our study suggests that Australian universities are a long way from achieving this. In the absence of clear national leadership, it is vital that such institutions work collaboratively to build consensus around effective open access policy development. Further research in this area, to better understand the key stakeholders and organisational processes at play, and identify the appropriate mechanisms for collaboration, would undoubtedly be beneficial.

The stated intention of the policies analysed in this study differ markedly, ranging from increasing the impact of the institution’s research outputs, to increasing the profile of the institution, to improving society. None of these rationales are problematic in themselves, however the disparity across the policies indicates a lack of shared purpose. The policies serve different purposes within institutions. It is interesting that of all of the policies, only two mention the position that "publicly funded research should be publicly available", which has been a longstanding justification for open access. For Australia to have a position on open access, reflecting activity in Europe, it will be necessary to come to an agreed position on why open access is needed.

Clarity on author processing charges

Our analysis of the varied positions on paying for publication, whether as gold or hybrid, indicates that Australia is very far from putting forward a unified position on author processing charges. As well as the general and overarching point that this lack of consistency is confusing for researchers, this is particularly significant given the recent shift to what are becoming known as transformative deals between academic libraries and publishers. These incorporate the costs of publication and the costs of subscriptions with a general aim of reducing overall costs or at least remaining cost neutral (Hinchcliff, 2019). In order to assess the value of a proposed deal to an institution, there is a pressing need to understand the institutional expenditure on processing charges. In Australia, where such charges are mostly paid by individual grant holders and not centrally managed, it is difficult to determine the level of expenditure on them. Attempts to identify this figure date back to 2014 (Kingsley, 2014).

In Australia, group negotiations on content procurement are managed by the Council of Australian University Librarians through a consortium. In October 2019, the Council announced the first transformative agreement for Australia and New Zealand with the UK-based Microbiology Society, which provides the university libraries the ability to pay a single 'publish and read' fee for uncapped open access publishing in all of the Society’s journals by corresponding authors (CAUL, 2019).

During 2019 CAUL commenced a project to design and implement a consistent process for collection and reporting of author processing charges (Cramond et al., 2019). As transformative deals become more common in the Australian landscape, the need to have clearer policies relating to these charges, and a better understanding of their expenditure at an institutional and national level becomes more urgent. This in turn requires institutions to develop consistent policies on funding author processing charges, and clearer guidance for researchers on their use.

Timing of deposits

Only thirteen of the twenty open access policies were found to specify a deadline for deposit of papers into a repository. In many of those 13 we found inconsistency, and a conflation between instructions to ‘deposit work’ and ‘make the work openly accessible’ in the language of the policies. ‘Deposit’ and ‘make open’ are different actions and clear differentiation of the two in any open access policy would assist researchers. For example, if a policy states that a work must be deposited on publication, yet there is a publisher embargo on open OA, then the work must initially not be open access and only be available as a metadata-only record in the repository. The full work may only be made openly accessible once the embargo period is complete. It is essential that those responsible or drafting policy understand the challenges for researchers associated with understanding this complex space, and draft policy accordingly. As there is a positive correlation between requiring deposit closer to acceptance (rather than on or after publication) (Larivière and Sugimoto, 2018), compliance policies should ideally stipulate both when a work needs to be deposited into a repository, and when the work needs to be made open access. Thus, there are significant operational implications of not clarifying this differentiation, and not noting when a deposited item is subject to a publisher embargo.

Conclusion

We have reported in detail the results of a content analysis of formal institutional open access policies at Australian universities. Just twenty of forty-one Australian universities were found to have such a policy, despite the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research requiring universities to publish "policies and mechanisms that guide and foster the responsible publication and dissemination of research" (Australian Government, 2018). Within the twenty analysed policies we found extensive variation across a number of crucial areas, including paying for publication, deposit timing, and the intent and rationale underpinning the policies. In addition, we found only three policies which explicitly stated the consequences for non-compliance.

There is growing impetus towards the development of a national open access strategy in Australia. The new Australian Chief Scientist, Dr Cathy Foley, has indicated her support for a unified approach, a move welcomed by advocacy groups (CAUL and AOASG, 2021). Our findings show how vital consensus building and standardisation will be as part of this process. We suggest that there is an urgent need for collaborative, inclusive and detailed discussions involving a range of stakeholders, to ensure that there is not only a common goal, but a clearly defined framework, including consistent and effective institutional policy development and implementation, to achieve that goal.

About the authors

Dr Simon Wakeling is a lecturer in the School of Information and Communication Studies at Charles Sturt University. His research focuses on the means of delivering free and equitable access to information, with specific interests in scholarly communication, and public libraries. He can be contacted at swakeling@csu.edu.au

Dr Danny Kingsley is a thought leader in the international scholarly communication space. She is Associate Librarian, Content and Digital Library Strategy at Flinders University and Visiting Fellow at the Australian National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science. She can be contacted at danny.a.kingsley@gmail.com.

Dr Hamid R. Jamali is an Associate Professor at the School of Information and Communication Studies at Charles Sturt University, Australia. His research interests are in the broad areas of scholarly communication and bibliometrics. He can be contacted at h.jamali@gmail.com

Dr Mary Anne Kennan conducts research that focuses broadly on scholarly communication including open access and research data management; the education of, and roles for, librarians and information professionals; and the practices of information sharing and collaboration in various contexts. She can be contacted at mkennan@csu.edu.au

Dr Maryam Sarrafzadeh is a faculty member at the School of Information Science and Knowledge Studies, University of Tehran. She is also an adjunct lecturer in the School of Information Studies, Charles Sturt University. Maryam's research interests include digital literacy, scholarly communication and bibliotherapy. She can be contacted at m.sarrafzadeh@ut.ac.ir

References

Note: A link from the title, or from (Internet Archive) is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020, May 20). Research and experimental development, higher education organisations, Australia, 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/technology-and-innovation/research-and-experimental-development-higher-education-organisations-australia/latest-release (Internet Archive)

- Australian FAIR Access Working Group. (2022). Policy statement on F.A.I.R. access to Australia’s research outputs. https://www.fair-access.net.au/fair-statement (Internet Archive)

- Australian Government. (2018). Publication and dissemination of research: a guide supporting the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/15569/download?token=LJspzrVd (Internet Archive)

- Australasian Open Access Strategy Group (2019). What is open access? https://archive.oaaustralasia.org/what-is-open-access/ (Internet Archive)

- Australian Research Council (2021). ARC open access policy. https://www.arc.gov.au/policies-strategies/policy/arc-open-access-policy/arc-open-access-policy-version-20211 (Internet Archive )

- Awre, C., Beeken, A., Jones, B., Stainthorp, P., & Stone, G. (2016). Communicating the open access policy landscape. Insights, 29(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.308

- Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. (2003). https://openaccess.mpg.de/67605/berlin_declaration_engl.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Bexley, E., James, R., & Arkoudis, S. (2011). The Australian academic profession in transition: addressing the challenge of reconceptualising academic work and regenerating the academic workforce. Centre for the Study of Higher Education.

- Bosman, J., De Jonge, H., Kramer, B., & Sondervan, J. (2021). Advancing open access in the Netherlands after 2020: from quantity to quality. Insights, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.545 (Internet Archive)

- Boufarss, M., & Laakso, M. (2020). Open Sesame? Open access priorities, incentives, and policies among higher education institutions in the United Arab Emirates. Scientometrics, 124(2), 1553–1577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03529-y

- Budapest Open Access Initiative. (2002). Declaration. https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read/ (Internet Archive)

- Callan, P. (2014, July 17). Joining the dots: connecting publications with grants, data, and other scholarly outputs. Presentation at ANDS Webinar.https://eprints.qut.edu.au/74127/1/70124.pdf

- CAUL. (2019, October 17). First transformative agreement for Australia and New Zealand. https://www.caul.edu.au/news/first-transformative-agreement-australia-and-new-zealand (Internet Archive)

- CAUL, & AOASG. (2019, May 9). Joint CAUL-AOASG election statement. https://www.caul.edu.au/news/joint-caul-aoasg-election-statement (Internet Archive)

- CAUL, & AOASG. (2021). CAUL and AOASG welcome Chief Scientist’s commitment to open access for Australian research. Open Access Australasia. https://oaaustralasia.org/2021/03/23/caul-and-aoasg-welcome-chief-scientists-commitment-to-open-access-for-australian-research (Internet Archive)

- cOAlition S. (2021). "Plan S" and "cOAlition S": accelerating the transition to full and immediate open access to scientific publications. https://www.coalition-s.org/ (Internet Archive)

- Cochrane, T., & Callan, P. (2007). Making a difference: implementing the eprints mandate at QUT. OCLC Systems & Services: International Digital Library Perspectives, 23(3), 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/10650750710776396

- Cramond, S., Barnes, C., Lafferty, S., Barbour, V., Booth, D., Brown, K., Costello, D., Croker, K., O’Connor, R., Rolf, H., Ruthven, T., & Scholfield, S. (2019). Fair, affordable and open access to knowledge: the CAUL Collection and Reporting of APC Information Project. In Proceedings of the IATUL Conferences, paper 2. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2258&context=iatul. (Internet Archive)

- Crowfoot, A. (2017). Open access policies and science Europe: state of play. Information Service and Use, 37(3), 271–274. https://doi.org/10.3233/ISU-170839 (Internet Archive)

- Curtin Open Knowledge Initiative. (2020). Evolution of green and gold OA. Countries: open access over time. Curtin University. https://storage.googleapis.com/oaspa_talk_files/country_scatter.html (Internet Archive)

- European Commission. (2016). Guidelines to the rules on open access to scientific publications and open access to research data in Horizon 2020.. https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/oa_pilot/h2020-hi-oa-pilot-guide_en.pdf (Internet Archive)

- European Commission. (n.d.a). Open access & data management: H2020 online manual. https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/docs/h2020-funding-guide/cross-cutting-issues/open-access-dissemination_en.htm (Internet Archive)

- European Commission. (n.d.b). Trends for open access to publications. Open Science Monitor. https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/strategy/strategy-2020-2024/our-digital-future/open-science/open-science-monitor/trends-open-access-publications_en (Internet Archive)

- Foley, C. (2021, March 17). National Press Club address. https://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/Dr-Cathy-Foley-delivers-National-Press-Club-Address (Internet Archive)

- Fruin, C., & Sutton, S. (2016). Strategies for success: open access policies at North American educational institutions. College & Research Libraries, 77(4), 469–499. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.4.469 (Internet Archive)

- Herrmannova, D., Pontika, N., & Knoth, P. (2019). Do authors deposit on time? Tracking open access policy compliance. In 2019 ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL), 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1109/JCDL.2019.00037

- Higher Education Funding Council for England. (2019). REF 2021: Overview of open access policy and guidance. The Council. https://www.ref.ac.uk/media/1228/open_access_summary__v1_0.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Hinchcliff, L. (2019, April 23). Read-and-publish? Publish-and-read? A primer on transformative agreements by @lisalibrarian. The Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2019/04/23/transformative-agreements/ (Internet Archive)

- Hoops, J., & McLaughlin, M. (2020, April 22). The open access policy in action: automating author’s rights. Digital Library Brown Bag Series. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/handle/2022/25408

- Huang, C.-K. (Karl), Neylon, C., Hosking, R., Montgomery, L., Wilson, K. S., Ozaygen, A., & Brookes-Kenworthy, C. (2020). Meta-research: evaluating the impact of open access policies on research institutions. ELife, 9, e57067. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.57067 (Internet Archive)

- Hunt, M., & Picarra, M. (2016). Open access policy alignment. PASTEUR4OA. http://www.pasteur4oa.eu/sites/pasteur4oa/files/resource/Briefing%20paper%20-%20policy%20alignment%20final_0.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Kern, B., & Wishnetsky, S. (2014). Adopting and implementing an open access policy: the library’s role. The Serials Librarian, 66(1–4), 196–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2014.880035

- Kingsley, D. (2011). Support for open access in Australia: an overview. [PowerPoint slides]. In PKP third International Scholarly Publishing Conference, September 26 - September 28, 2011. https://conference.pkp.sfu.ca/index.php/pkp2011/pkp2011/paper/view/271 (Internet Archive)

- Kingsley, D. (2013, October 31). Open access developments in Australia. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/10793

- Kingsley, D. (2014, April 14). What are we spending on OA publication? Australasian Open Access Strategy Group. https://aoasg.org.au/what-are-we-spending-on-oa-publication/ (Internet Archive)

- Kingsley, D., & Boyes, P. (2016, October 24). Who is paying for hybrid?. Unlocking Research: Open Research at Cambridge. https://unlockingresearch-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=1002 (Internet Archive)

- Kipphut-Smith, S. (2014). "Good enough": developing a simple workflow for open access policy implementation. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 21(3–4), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2014.932263

- Kirkman, N., & Haddow, G. (2020). Compliance with the first funder open access policy in Australia. Information Research, 25(2), paper 857. http://www.informationr.net/ir/25-2/paper857.html (Internet Archive)

- Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2018). Do authors comply when funders enforce open access to research? Nature, 562(7728), 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07101-w

- Luo, Q., Xia, J. C., Haddow, G., Willson, M., & Yang, J. (2018). Does distance hinder the collaboration between Australian universities in the humanities, arts and social sciences? Scientometrics, 115(2), 695–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2686-x

- Morais, R., Saenen, B., Garbuglia, F., Berghmans, S., & Gaillard, V. (2021). From principles to practices: open science at Europe’s universities. European University Association. https://www.eua.eu/downloads/publications/2021%20os%20survey%20report.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Morrison, C., Secker, J., Vezina, B., Ignasi Labastida I Juan, & Proudman, V. (2020). Open access: an analysis of publisher copyright and licensing policies in Europe, 2020. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4046624 (Internet Archive)

- National Health and Medical Research Council (2018). Open access policy. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/attachments/resources/nhmrc-open-access-policy_final_28april2020.pdf (Internet Archive)

- National Institutes of Health. (2008). NIH public access policy details. https://publicaccess.nih.gov/policy.htm (Internet Archive)

- National Institutes of Health. (2012, November 16). NOT-OD-12-160: upcoming changes to public access policy reporting requirements and related NIH efforts to enhance compliance. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-12-160.html (Internet Archive)

- National Open Research Forum. (2019). National framework on the transition to an open research environment: Digital Repository of Ireland. https://repository.dri.ie/catalog/0287dj04d

- Open Science Coordination in Finland, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies. (2020). Declaration for open science and research (Finland) 2020-2025. The Committee for Public Information (TJNK) and Federation of Finnish Learned Societies (TSV) https://avointiede.fi/fi/julistus (Internet Archive)

- NIH Public Access Working Group. (2005). Meeting summary. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/od/bor/PublicAccessWG-11-15-05.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Orzech, M. J., & Myers, K. (2020). Adopting an open access policy at a four-year comprehensive college. In D. Chase & D. Haugh (Eds.), Open praxis, pen access: digital scholarship in action (pp. 69–77). ALA Editions. https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=drakepubs

- Otto, J. J., & Mullen, L. B. (2019). The Rutgers open access policy goes into effect: faculty reaction and implementation lessons learned. Library Management, 40(1/2), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-10-2017-0105

- Payne, G., & Payne, J. (2004). Content analysis. Chapter 10 in Key concepts in social research. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209397

- Phillips, D. (2020, October 20). No double dipping! The rise of transformative publisher agreements in the transition to full open access. Open Access and Digital Scholarship Blog. https://blogs.imperial.ac.uk/openaccess/2020/10/20/no-double-dipping-the-rise-of-transformative-publisher-agreements-in-the-transition-to-full-open-access/ (Internet Archive)

- Pinfield, S., Wakeling, S., Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2020). Open access in theory and practice: the theory-practice relationship and openness. Taylor and Francis.

- Poynder, R. (2009, May 23). Open access mandates: judging success. Open and Shut? https://poynder.blogspot.com/2009/05/open-access-mandates-judging-success.html (Internet Archive)

- Rieck, K. (2019). The FWF’s open access policy over the last 15 years: developments and outlook. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3060200 (Internet Archive)

- Robinson-Garcia, N., Costas, R., & van Leeuwen, T. N. (2020). Open access uptake by universities worldwide. PeerJ, 8, e9410. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9410 (Internet Archive)

- Saarti, J., Rosti, T., & Silvennoinen-Kuikka, H. (2020). Implementing open science policies into library processes: case study of the University of Eastern Finland library. LIBER Quarterly, 30(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.18352/lq.10336

- Soper, D. (2017). On passing an open access policy at Florida State University: from outreach to implementation. College & Research Libraries, 78(8), 432–463. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.78.8.432 (Internet Archive)

- Study Australia. (2022). List of Australian universities. https://www.studyaustralia.gov.au/english/study/universities-higher-education/list-of-australian-universities/list-of-australian-universities (Internet Archive)

- Suber, P. (2008). An open access mandate for the National Institutes of Health. Open Medicine, 2(2), e14-e16. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4723860

- Suber, P. (2012). Open access. MIT Press.

- Swan, A., Gargouri, Y., Hunt, M., & Harnad, S. (2015). Open access policy: numbers, analysis, effectiveness. ArXiv, 1504.02261. http://arxiv.org/abs/1504.02261

- Swedish Research Council. (2015). Proposal for national guidelines for open access to scientific information. https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2015-03-02-proposal-for-national-guidelines-for-open-access-to-scientific-information.html (Internet Archive)

- Tennant, J. P., Waldner, F., Jacques, D. C., Masuzzo, P., Collister, L. B., & Hartgerink, C. H. J. (2016). The academic, economic and societal impacts of open access: an evidence-based review. F1000Research, 5, 632. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.8460.3 (Internet Archive)

- UK Research and Innovation. (2021). Making your research publications open access. https://www.ukri.org/apply-for-funding/before-you-apply/your-responsibilities-if-you-get-funding/making-research-open/ (Internet Archive)

- UNESCO (n.d.). What is open access? https://en.unesco.org/open-access/what-open-access (Internet Archive)

- University of Queensland. (2020). UQ governance and management framework. https://ppl.app.uq.edu.au/content/1.00.01-uq-governance-and-management-framework (Internet Archive)

- Van Noorden, R. (2013, July 2). NIH sees surge in open-access manuscripts. Nature News Blog. http://blogs.nature.com/news/2013/07/nih-sees-surge-in-open-access-manuscripts.html (Internet Archive)

- Wellcome Trust. (2012, June 28). Wellcome Trust strengthens its open access policy. https://wellcome.org/press-release/wellcome-trust-strengthens-its-open-access-policy (Internet Archive)

- Wellcome Trust. (2014, September). Independent review of the implementation of RCUK policy on open access: response from the Wellcome Trust. https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/wtp057467.pdf (Internet Archive)

- Wellcome Trust. (2019). Wellcome and COAF open access spend 2018/19. https://wellcome.org/grant-funding/wellcome-and-coaf-open-access-spend-201819 (Internet Archive)

- Wellcome Trust. (n.d.). Open access policy. https://wellcome.org/grant-funding/guidance/open-access-guidance/open-access-policy (Internet Archive)

- Zhu, Y. (2017). Who support open access publishing? Gender, discipline, seniority and other factors associated with academics’ OA practice. Scientometrics, 111(2), 557–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2316-z (Internet Archive)

How to cite this paper

Appendices

List of universities included in the study

| University | Abbreviation |

|---|---|

| Australian Catholic University | ACU |

| Australian National University | ANU |

| Bond University | Bond |

| Central Queensland University | CQU |

| Charles Darwin University | CDU |

| Charles Sturt University | CSU |

| Curtin University | CU |

| Deakin University | DU |

| Edith Cowan University | ECU |

| Federation University | |

| Flinders University | |

| Griffith University | |

| James Cook University | JCU |

| La Trobe University | |

| Macquarie University | |

| Monash University | |

| Murdoch University | |

| Queensland University of Technology | QUT |

| RMIT University | RMIT |

| Southern Cross University | SCU |

| Swinburne University of Technology | SUT |

| Torrens University | |

| University of Queensland | UQ |

| University of Adelaide | Adelaide |

| University of Canberra | |

| University of Divinity | |

| University of Melbourne | |

| University of New England | UNE |

| University of New South Wales | UNSW |

| University of Newcastle | |

| University of Notre Dame | UND |

| University of South Australia | UniSA |

| University of Southern Queensland | USQ |

| University of Sydney | |

| University of Tasmania | |

| University of Technology Sydney | UTS |

| University of the Sunshine Coast | USC |

| University of Western Australia | UWA |

| University of Wollongong | Wollongong |

| Victoria University | |

| Western Sydney University | WSU |