Audiobook apps: exploring reading practices and technical affordances in the player features

Elisa Tattersall Wallin

Introduction. Audiobooks are increasing in popularity and are now widely used through apps from subscription services. While these apps are part of audiobook practices, there is scant research on this topic. This article contributes to an understanding of the audiobook player function and the features therein.

Method. The article builds on an interview study with ten young Swedish users and a study of the apps from subscription services Storytel, BookBeat and Nextory.

Analysis. The player functions in the apps were explored using a feature analysis and the interview material was analysed using qualitative content analysis. The focus was on affordances of the different app features, and how these related to audiobook reading practices.

Results. There were ten to twelve features each in the different players. Four common user practices emerged in the interview material: adjusting the speed, selecting a track, setting a sleep timer and rewinding the audiobook.

Conclusions. The apps play a significant part of audiobook reading practices. However, while the apps afford certain practices, some features create hindrances to other reading practices.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper943

Introduction

Digital audiobooks are widely used through mobile apps available from subscription services. These apps function both as libraries and as players for listening. Previously, digital audiobooks were primarily downloaded from an online shop and listened to via a digital music player, such as iTunes. As there was no bookmarking feature, this meant users had to keep track of where they were in the book (Have and Pedersen, 2021). The emergence of apps specifically for digital books therefore created new possibilities for the user. Although the apps and their design may play a significant role in audiobook reading practices today, there is little research on the apps, their features, or on how they are used by subscribers.

This article explores the player function within apps from three subscription services offering digital audiobooks. The player is used for listening and is the function users interact with when actively engaging with an audiobook. This is therefore the part of the apps which plays the largest role in contemporary audiobook reading practices, and as such it is the focus of the analysis in this study. Besides the player, two other functionalities can be distinguished in these subscription service apps. The first is the subscription function with account details and links to the platform webpage where subscription settings can be changed. The subscription is what enables usage of the content on the app. The second functionality is the library with the catalogue of books, which includes features for searching and for browsing different categories, book recommendations and a personal digital bookshelf of saved books. Managing subscriptions and searching for new books are supplementary functionalities which enable reading activities to be carried out. However, these functionalities are not explored further in this study.

This article is part of a larger project which aims to develop knowledge about contemporary audiobook practices in the context of subscription services. In an interview study with ten Swedish young adults who were avid users of audiobooks, it became evident that the design of the apps has consequences for audiobook reading practices. This is part of the materiality of reading, that is, how the tools used in reading relate to how reading can be carried out and experienced. Therefore, this article explores some technical affordances of the player function in audiobook apps and related reading practices among these young users. In focus are apps from the three subscription services Storytel, BookBeat and Nextory. These all originate from Sweden, where they are the dominating subscription services on the market. All three operate internationally as well. These different services have between 500 000 to 1,7 million subscribers, with Storytel being the largest actor (Dahlgren, 2021a; 2021b; 2022). While they offer e-books alongside audiobooks in their apps, the focus here is solely on audiobooks and features related to them. In Sweden, audiobooks are significantly more popular than e-books and subscription services are the largest providers of audiobooks to users (Wallin et al., 2021; Wikberg, 2021). There are other apps used for audiobook listening, such as those offered by libraries or online bookshops, these are not included in this study.

The aim of this study is to explore features of the audiobook player in the three apps, and how these are used by young audiobook listeners, in order to identify affordances (using this term in the sense used by Gibson (1977 ) outlined below) of the features and how they enable or constrict audiobook reading practices. This aim is fulfilled with interviews with ten young Swedish users of the audiobook apps and a feature analysis of the three apps, focusing on the audiobook player function.

Audiobook subscription services and apps – a background

Audiobook publishing has consistently been at the forefront of technological innovation (Colbjørnsen, 2015). There are numerous examples of how audiobook technology has been state-of-the-art throughout the audiobooks’ century-long history. Long-playing records in the post-war era were revolutionary due to their durability and capacity to hold longer recordings compared to previous formats, such as the 78 rpm phonograph records which only held a few minutes (Rubery, 2016). Cassette tapes and the invention of car stereos and later Walkmans, helped make the audiobook suitable for commuting (Colbjørnsen, 2015; Whitten, 2002). Today, this innovation continues with digital audiobooks, mobile apps and streaming technology. There are now several subscription services for digital books on the international market, such as Audible, Scribd, Storytel, Nextory, Kindle Unlimited and BookBeat. Some of these services offer both audiobooks and e-books while others only supply audiobooks.

The introduction of subscription services for digital books is part of a larger trend, namely the advancement of streaming services for all types of media, e.g., music, podcasts and film. The evolution and momentum of media streaming services can be connected to a widespread adoption of smartphones and improvement of Internet access and speed (Colbjørnsen, 2021). Subscription services for digital books are a significant part of the book market today, both in Sweden and internationally (Have and Pedersen, 2020; Rivas-Garcia and Magadan-Diaz 2022; Wikberg, 2021). These services operate in slightly different ways, but the three in focus here all follow a library model (Tattersall Wallin, 2021). This means that subscribers gain access to the collection of books in the app but are unable to keep the books. The monthly subscription fee is between 10-20 Euros per month, depending on the service and type of account chosen. The premium accounts give full access to the whole catalogue, allowing users to read as many books as they want every month. Lower-cost subscriptions are offered by BookBeat and Nextory, who have implemented time-limitations, such as 30 or 100 hours of listening allowed per month. All three services also have family subscriptions, where 2-6 people can create individual profiles within the same account for an additional cost.

When streaming subscription services are used with smartphones, the access to their content is enabled by apps (Colbjørnsen, 2021). App is short for application, and they are software programmes developed for mobile devices like smartphones and tablets. Typically, these come with default settings, and users have limited possibilities to adjust these. In contrast to applications running on a computer, apps are primarily cloud-based and lose some of the functionality offline. Apps are a significant part of media consumption today.

A feature of the library function in the subscription service apps is book reviews and ratings created by the users (Linkis, 2021). In all of the studied apps, users can either write short reviews or give star ratings to the book as well as the audiobook narrator. Lists of beststreamers, the streaming equivalent of bestsellers, reveal which books are most popular among the users in the app (Berglund, 2021). Along with these lists, there are book recommendations that are presented according to different categories or themes. Such recommendations appear to be curated by staff, often reflecting current events. There are also algorithmically created personal recommendations based on previous reading choices of individual subscribers. This is similar to other media streaming services like Netflix and Spotify where recommendation systems are used to promote content and make the service feel relevant to consumers so that they continue to use it (Floegel, 2021; Hallinan and Striphas, 2016). However, such recommendation systems are based on vague methods for collecting user data and have been found to promote content of a limited or biased nature (Eriksson and Johansson, 2017; Floegel, 2021; Hallinan and Striphas, 2016).

Reading practices and technical affordances

The theoretical concept of practice is here used to study what users do with the audiobook apps. Audiobook listening is here understood as a reading practice and conceptualised as reading by listening (Tattersall Wallin, 2021). Practices are here understood as comprising of routinised activities people do in time and space with material tools (Schatzki, 2005; 2009). Reading practices consist of a number of different activities where people engage with text in some form, using different senses (Tattersall Wallin, 2021). In this study on audiobook reading practices performed with the help of mobile apps, the design of the apps may be related to how reading can be carried out. Schatzki notes that those who design and build ‘material arrangements have a special hand in configuring practices’ (2009, p. 46). However, the power over practices is limited for any designer, as they themselves are informed by existing practices, that is, how people already do things. Those who use the designs will also adapt it to suit their own needs and the activities they already carry out in their everyday lives (Schatzki, 2009).

The concept of affordance will be used here to discuss user practices in relation to technical features of the apps. Affordance was originally introduced by Gibson (1977) in regard to how animals, and humans, perceive which actions become possible with natural objects. In this article, the understanding of affordance follows the use of the concept within Library and Information Science studies on social media platforms (for e.g., Gunnarsson Lorentzen, 2016) and within Human Computer Interaction (Fragoso et al., 2012; Kaptelinin and Nardi, 2012). Affordances are here understood in relation to how the user can interact with the interface (Fragoso et al., 2012). The focus is on mobile applications and how their design affords for certain actions, making others either more difficult or impossible. Kaptelinin and Nardi (2012) highlight two aspects of affordances, first how the user can interact with the technology, and second, what happens when they do so. As an example, a feature such as a scroll bar enables the user to drag the bar, which in turn means a particular portion of a document or webpage is visible on the screen. In the context of audiobook apps, a play symbol functions as a button which is possible to tap, and when a user taps on that part of the screen the audiobook begins to play.

Method

The empirical material for this article has been collected first through an interview study with audiobook users, and second a feature analysis of three audiobook subscription service apps.

The interview study

The focus of the interviews was on the respondents’ audiobook reading practices, exploring the tools used for audiobook reading, as well as how, when and where their listening was performed. From the interview study it emerged that several activities were related to features in the subscription service apps used by the respondents, and this is the part of the material in focus in this article. The interview material concerning the apps and related practices was analysed thematically, applying a form of qualitative content analysis. Four themes of app-related reading practices emerged in the analysis and will be explored in this article. These are practices which are afforded by features in the apps

The interview study consisted of ten semi-structured interviews with teenagers from different parts of Sweden. All respondents were avid audiobook listeners and users of one of the three major Swedish audiobook subscription services: Storytel, BookBeat and Nextory. A few of the respondents had experience of using multiple subscription services, however most had only used one of them. The respondents were recruited through their upper secondary schools, volunteering after receiving information about the study through their virtual learning platform or school library. They were 18 or 19 years old at the time of the interview and gave their own consent to participate. Eight of the respondents were young women, and two were young men. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority and followed the European General Data Protection Regulation. As appreciation for their participation, the respondents received a nominal gift certificate to a film streaming service. All interviews were carried out between May and November of 2020 via video call and lasted around 30-45 minutes. The audio from the interviews was recorded and transcribed in Swedish by the author for further analysis. The quotes by respondents included in the article were translated into English by the author. In order to protect the identity of the respondents, pseudonyms (P1-P10) will be used in this article.

The app feature analysis

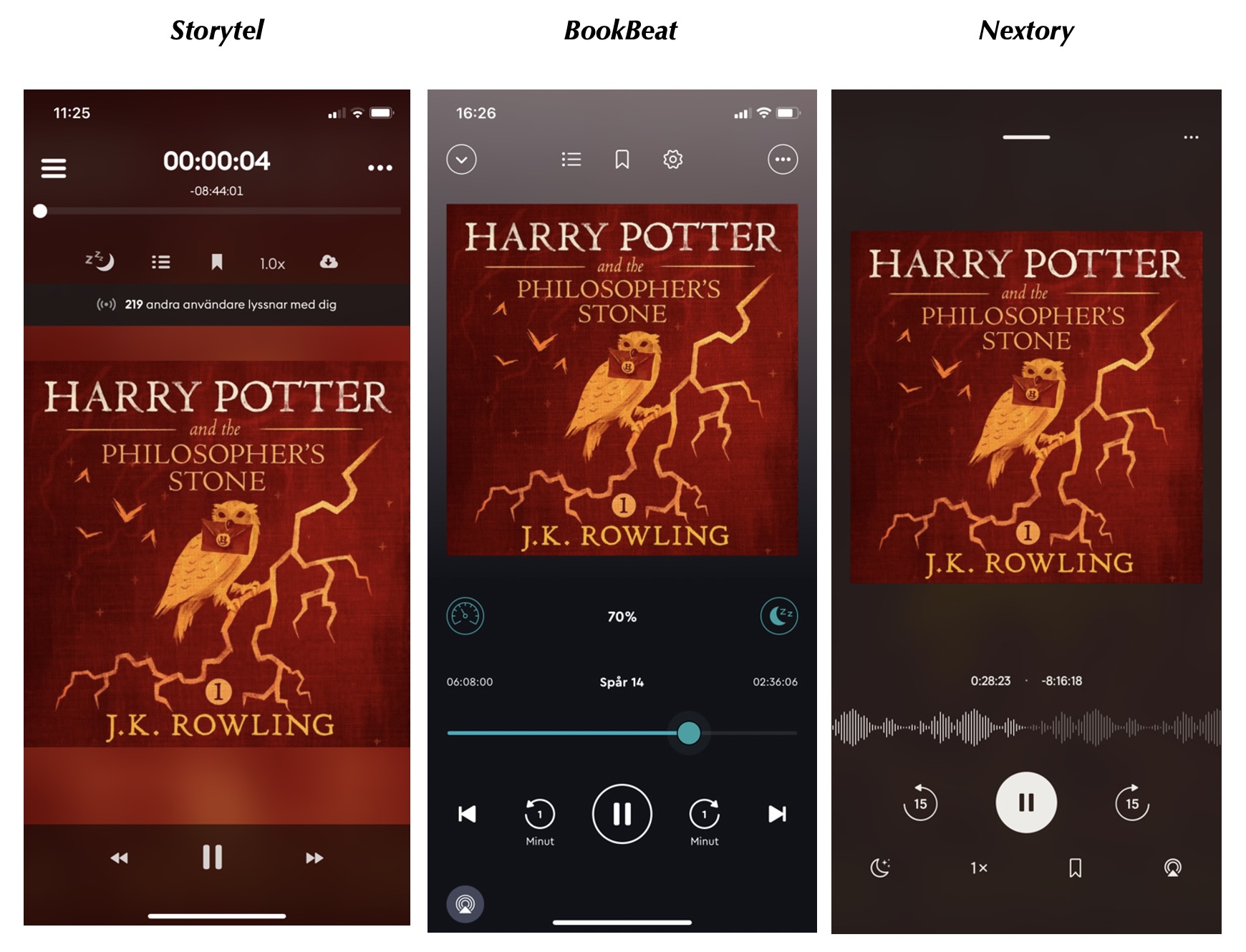

In the next step, the author carried out a feature analysis within the three different apps. This was done in order to further understand the features described in the interviews. Feature analysis is a digital method which involves studying the interface of webpages or apps and exploring the features available, the level of interactivity they allow the user and comparing the features and functionalities of different apps (Rogers, 2013). The feature analysis focused on the audiobook player in each app, exploring the features available on the screen when an audiobook is playing. In order to make the feature analysis of the different audiobook players as comparable as possible, the same audiobook title was accessed in all three apps. This was to make sure that features would not differ between different books. The chosen title was Harry Potter and the Philosophers Stone, written by J.K. Rowling and narrated by Stephen Fry, as this was mentioned by most of the respondents.

The material for the app study was collected in February 2021. The different features of the audiobook player in the apps were explored in full by the author. These were all then described in detail in a spreadsheet where they were categorised by the different types of features found within each app. To enable continued comparison and analysis after data collection, screenshots were taken of the audiobook player screen in each app, as well as of each feature available in the players. In total, eight pages of notes and 22 screenshots were used for the analysis and comparison of the different features, their affordances and constraints. It is worth noting that the subscription services continuously update the app interfaces and that changes may occur after this study concluded, and that some changes may have occurred between the interviews in 2020 and the feature analysis in early 2021.

Results

The empirical material will be analysed in this section. The four themes which emerged in the interview analysis, along with the four related player features, will be explored in-depth. First however, all features available in the audiobook players are outlined in table 1, where the presence or absence and function of the features in the three apps are summarised. The features have here been divided into three categories which emanated from the analysis: play features, progress features and streaming features. Where a feature is not available in one of the apps, it is marked as not available (N/A). Most features are accessed by tapping the related symbol in the player, which then opens a new screen for that feature. Once a setting has been made, the user is returned to the player screen.

| FEATURE/APP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Storytel | BookBeat | Nextory | |

| PLAY FEATURES | |||

| Play/pause | Play symbol converts into pause symbol when book is playing. There is no stop feature, pause functions as full stop | Play symbol converts into pause symbol when book is playing. There is no stop feature, pause functions as full stop | Play symbol converts into pause symbol when book is playing. There is no stop feature, pause functions as full stop |

| Rewind/fast forward | Set to 15 seconds | Adjustable from 15 seconds to 30 minutes | Set to 15 seconds |

| Select track | Tapping track symbol opens list of all tracks in the audiobook with timestamps | Features in player for switching to next/previous track. Another symbol leads to list of all tracks | N/A |

| Sleep timer | Adjustable from 0–23 hours and 0–59 minutes | Adjustable 0–120 minutes, with option to set timer until end of track | Adjustable from 0–23 hours and 0–59 minutes |

| Sleep timer display | 4 pre-set timer options and manually adjustable scrollable timer | Options for end of track and 2 pre-set timers, and manually adjustable bar | 4 pre-set timers and manually adjustable scrollable timer |

| Adjust speed | 6 pre-set speed options: 0,75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2.0. | Manually adjustable between 0.5–2.0. | Manually adjustable between 0.5–2.0. |

| Adjust speed display | Opens list with the 6 speeds | Screen with 3 suggested speeds and manually adjustable bar | Screen with 4 suggested speeds and manually adjustable scroller |

| Bookmark | Timestamped bookmarks are set by tapping symbol | Timestamped bookmarks showing place in percent are set by tapping symbol | Timestamped bookmarks are set by tapping symbol |

| Bookmark note feature | Notes can be written to accompany bookmarks | Notes can be written to accompany bookmarks | N/A |

| PROGRESS FEATURES | |||

| Progress line | Straight line with circle indicating place in book | Straight line with circle indicating place in book | Grey sound waves with played parts in white |

| Time indicators | Hours, minutes and seconds played and remaining in book are displayed | Hours, minutes and seconds played and remaining are displayed with track number and percentage of book | Hours, minutes and seconds played and remaining in book are displayed |

| Sleep timer countdown | When a timer is set, a countdown clock in player shows time left until timer stops the book | When a timer is set, a countdown clock in player shows time left until timer stops the book | When a timer is set, a countdown clock in player shows time left until timer stops the book |

| STREAMING FEATURES | |||

| Stream book | Books are streamed unless downloaded | Books are streamed unless downloaded | N/A |

| Download book | Tapping symbol downloads books for offline listening | Books are downloaded through player settings menu for offline listening | Books are immediately downloaded once they start playing. |

Screenshots of the player function in each app are included here in figure 1 in order to visualise the different features outlined in table 1. These were taken in February 2021 and are included with permission from Storytel, BookBeat and Nextory.

Adjusting the speed

As noted in table 1, all three apps have a feature allowing users the option of adjusting the speed of the audiobook. While Storytel has six pre-set speeds to choose from, BookBeat and Nextory allow manual adjustment of the speed from anywhere between 0.5–2.0. The default speed at which the audiobook was recorded is 1.0. After the settings have been adjusted the new speed will be displayed in the player.

It appears that the purpose of the reading is central to whether the interview respondents choose to adjust the speed or not. There are usually different motives when reading for school as opposed to reading for leisure. When reading a novel for school, the student knows that there will be a test, an essay or a seminar where they will need to unpack the themes of the novel, reflect on character arcs or discuss how the story can be understood in the context it was written. This puts an emphasis on understanding the bigger picture and looking for motifs to analyse. With leisure reading on the other hand, the focus is more likely to be on enjoyment. The leisure reader may want to be amused, comforted or inspired, wish to expand their horizons or simply pass the time. Leisure reading is therefore more likely to involve taking the time to be in the moment and become immersed in the story. When reading for enjoyment there is no external pressure to recall the plot or characters from the book later on. On the one hand, this means that for leisure reading there is no requirement to focus intently on the audiobook, as respondents do not have to remember it in the same way as when reading for school. On the other hand, it is by concentrating that they are able to become immersed and can notice all the details, which is the expressed wish of the respondents.

Adjusting the speed is one of the most commonly mentioned features among the respondents in the interview study, particularly in relation to school-assigned reading. Six of the respondents explain that they listen to the audiobook version of assigned novels. Adjusting to a higher speed affords them the possibility to complete their assigned reading more quickly. This can be helpful if respondents are short on time for the assignment. Even more so, this feature is used if a novel does not interest them. The respondents say that they want to get through assigned books as swiftly as possible. This is succinctly explained by one respondent: ‘a lot of the time I don’t like those books, and then I want it to go faster’ (P5). It seems that when the respondents are not given a choice over their own reading matter, they are more likely to feel uninspired by the reading. P6 talks about a recent experience of adjusting the speed for a school novel:

We’ve just read this book at school, and then you aren’t allowed to choose for yourself, so it is often a really dull book that you just need to get through. I can process things easily even if they are said very quickly. So, I put it on very fast, just to get through it. If the normal speed was at 100 percent, this was at maybe 210 percent. But then I couldn’t do anything else at the same time. (P6)

P6 has dyslexia and is accustomed to using audio for her reading. Over the years she has developed the ability to quickly process text using her sense of hearing. Despite this skill, she points out that when listening at twice the regular speed, she needs to sit down and focus solely on the book. Like most of the other respondents, multitasking while listening to an audiobook is usually an integral part of her reading practices. However, when listening at this pace, it is impossible for her to focus on two things at the same time. Another respondent, P9, had previously tried listening to a few assigned novels at around 1.5 speed. He found that it worked fine for his short-term memory, and that he was able to complete the assignments. However, in the long term he has realised that he has no memory of what those books were about and can only barely recall having listened to them.

P1 also listens at twice the speed for school assigned novels and finds that this usually works well. However, she points out that if it is a book that she enjoys, she wants to listen at the regular speed to take in all the details. This is something also firmly expressed by five other respondents, they want to take their time and savour books which they are reading for their own enjoyment. When reading for leisure, they are not under any time constraints to finish the book. This can be seen in how P2 says, ‘I don’t want it too fast or too slow, I want the natural speed’ (P2). These respondents note that by playing the book at a regular speed the reading experience becomes more comprehensive, or authentic.

Two respondents prefer to regularly listen at a slightly faster speed even when reading for leisure. P4 always listens to audiobooks while reading the book in print at the same time. This practice has helped her get out of a long reading slump. She prefers listening at 1.25 speed, so that the narrator’s pace matches her own. Sometimes she adjusts the player for an even faster speed, depending on the pace at which she is able to read by seeing at that moment. Another respondent, P3, feels that it is more efficient to consistently listen at 1.25 speed and that this enables him to get through more books. He has even adjusted the app settings so that audiobooks automatically begin playing at this chosen speed. He says, ‘it doesn’t make much of a difference for me, I got used to it sounding a little bit faster’ (P3). When listening at a slightly higher speed, it appears that reading comprehension and memory are not an issue for these two respondents, as long as they find the content interesting.

The idea of efficiency by listening at a faster speed is comparable to the objectives with traditional speed-reading practices of printed books. In its essence, traditional speed-reading involves skimming a text and being able to understand the meaning of a sentence without reading every word. By building up a rhythm in how they process the text, the reader can quickly get the gist but may lose out on the finer details (Baron, 2015). The respondents in this study appear to build up similar rhythms when speed-reading audiobooks and become used to the narration at a faster pace. Just like with traditional speed-reading, getting the gist of the story is the main focus for most respondents when speed-reading audiobooks.

Selecting a track

The select track feature allows the user to navigate between different parts of an audiobook, as the recordings consist of a number of timestamped tracks. In some recordings, the number of tracks correlates with the chapters, but others are divided into twice or three times as many tracks. The tracks will not be noticeable for the listener when playing the book, it is only if they want to select a particular track that they will encounter this feature. Tapping the track symbol in the Storytel and BookBeat apps opens a screen where all the tracks are listed. Already played tracks are marked, and users can tap a particular track so that the book begins playing from there. The BookBeat app also has a switch track feature in the audiobook player, next to the play and rewind/fast forward symbols. Tapping the switch track symbols makes the player skip to the previous or next track. As visible in table 1, there is no feature for selecting track in the Nextory app. Therefore, this practice is not possible for subscribers of that particular service.

This feature is found useful for some respondents, and confusing for others. Four of the interview respondents occasionally choose to alternate between reading the same book title in print and as an audiobook. These respondents switch between the book formats, selecting the one which suits them best in different situations. If they are going to be moving around outside or doing chores at home, the audiobook and reading by listening is preferred. However, if they have time to sit down, they chose the printed version instead. The select track feature is therefore used by respondents to navigate in the audiobook after they have been reading in the printed book. P7 recounts an experience when she combined the audiobook and printed book for a school assigned novel:

I found it worked really well. I read in the [printed] book sometimes and found it really easy to jump back and navigate to the right chapter in the audiobook so that I didn’t have to read the same thing several times. (P7)

P7 notes that it is easy to see in the app which chapter is being played, and that this feature aids these types of activities. When combining formats, it is important to keep track of where they are in the book, to make it easy to start in another format the next time, if needed. One respondent explains ‘I always make sure that I read to the end of a chapter, so that I can start there in the audiobook the next time’ (P1). This strategy is also used by the other respondents who have tried switching between formats.

However, not all find the feature intuitive. As the tracks do not always match the chapter numbers, a couple of the respondents have found it difficult to find their place in the audiobook. P3 sometimes alternates between the audio and print format when reading very long books. He notes that it is not always clear what the track numbers mean. He, therefore, tests a track, listening briefly to it, to see if he’s in the right place. It can therefore take some trial and error to find the right place in the audiobook. This vagueness has stopped another respondent from continuing to utilise the select track feature:

It’s a little tricky because it can be difficult to know where you are in the book in relation to the other format. I haven’t been able to understand the chapter thing because it isn’t always right, so then I tend to just stick to either the audiobook or the printed book. (P8)

The ambiguity of the feature has put constraints on a desired reading practice for P8. These apps do not come with any instruction manuals. Rather, the user is dependent on features being self-explanatory and easy to use. With the select track feature, it is not always clear how the tracks correlate with book chapters or how books are divided into tracks. This may make it more difficult for users who want to switch between book-formats. While P3 has accepted the inadequacies of finding the right track, this may not be true for all users. If a feature is difficult to use, it does not create the desired affordance, and some will choose not to use it.

The difference in experiences among the respondents may be related to how the number of tracks varies between different audiobook recordings, as noted at the beginning of this section. Audiobooks with tracks that closely relate to the chapters are easier to use than those which have many more tracks. Therefore, the affordance of the feature varies and can be related both to the feature design in the specific app and to the audiobook recording.

A couple of the respondents have also tried switching between audiobook and e-book formats in the apps. In the Storytel app, it is possible to switch seamlessly between the audiobook and e-book version. If a user listens to part of a book title as an audiobook, and then chooses to switch to the e-book version, they will be moved to the exact place in the e-book where they paused their listening. In the BookBeat and Nextory apps it is also possible to switch between formats, however the user will be moved to the beginning of the e-book no matter how much they have read in the audiobook. In all three apps this function is reliant on both the e-book and audiobook version being available in the app library, which is not the case for all titles.

Setting a sleep timer

All three apps have a sleep timer feature which enables the user to set a timer for how long they want the book to be playing. The screens in the Storytel and Nextory apps are similar, both allow the user to manually set the timer with scrollable timers ranging from 0-23 hours and 0-59 minutes (BookBeat 0–120 minutes). There are also four tappable pre-set timers, such as 15 minutes and an hour. BookBeat has three pre-set timers to choose from, one which stops at the end of the track and two which vary and appear to be based on previous timer settings made by the individual user. In all apps, after a timer is set the sleep timer symbol is highlighted in the audiobook player and a count-down clock shows how much time is left until the book stops.

This feature has likely been designed with the user in mind, with an affordance to aid their bedtime reading practices. Additionally, the feature may also have been made with the technology in mind as the action of putting the audiobook and the app to sleep does not have to be related to the user going to sleep. How the symbol for the feature is designed may inform about its intended use. All three apps have a crescent moon as the focal point of the sleep timer symbol. In both the BookBeat and Storytel apps the moon is surrounded by z’s, indicating that it is sleeping. In the Nextory app, the moon is instead surrounded by stars, which implies that the feature is for night-time use. As the feature varies slightly between the different apps, it may be that different affordances have been at the forefront in the app development. Since the BookBeat timer can be set for a maximum of 120 minutes, their designers have likely assumed that users who wish to set a timer will listen for two hours at most at the time. This may be based on their temporal log-data, showing how much users listen each day on average, and therefore informed by existing user practices (such data has been explored by Tattersall Wallin and Nolin, 2020). Storytel and Nextory enable the timer to be set for up to 23 hours and 59 minutes in their apps. This is longer than most audiobook recordings which may therefore render such a timer setting superfluous. However, it may have been a decision to leave the feature open as this affords for users to adapt it to their different needs.

Four of the respondents use the sleep timer feature regularly, and another two occasionally. All of them use it exclusively for bedtime reading. The timer is applied for two purposes, primarily to make sure that the book does not continue playing the whole night after the respondents fall asleep, but also to set a time limit on their bedtime reading. These respondents say that listening to an audiobook helps them relax and fall asleep, and that they usually fall asleep before the timer stops. If they are still awake when the timer stops, they may choose to set a new timer and listen a while longer. The time the respondents set the timer on varies between 15 minutes to an hour for different individuals. Without this feature, they would need to make sure to stop the book as soon as they started feeling sleepy, which could have an adverse effect on their relaxation. This is illustrated in a quote by one respondent, who has never used the timer and who also rarely listens at bedtime:

I have found that it is not a success [to listen at bedtime]. Because then I need to go back and look eight hours later where I was in the story. I can listen for maybe five minutes, but then I need to turn it off because I don’t know when I will fall asleep. (P9)

P9 finds that it is not relaxing to listen before falling asleep, as he is highly aware that he needs to remember to turn off the audiobook player. This, therefore, means that he avoids listening at bedtime. During the interview it appeared that P9 was not previously aware of the sleep timer feature. If users are unfamiliar with various features of the apps or how these can be employed in different situations, they will not utilise them. This can hinder desired reading practices.

Rewinding the audiobook

All three apps have rewind and fast forward features in the player, next to the play symbol. The BookBeat app is the only one which has adjustable settings for this feature, where users can set it from anywhere from 15 seconds up to 30 minutes. Meanwhile, this feature is set permanently to 15 seconds in the Storytel and Nextory apps. Being able to adjust the length of the rewind feature may be useful in some circumstances. For example, if a user has fallen asleep while listening, they may need to rewind several hours to find their place again. That could take some time with a 15 second rewind feature and it could then be beneficial to rewind for up to thirty minutes with one tap. However, if the user has been temporarily distracted by a text message, the 15 second setting may be just right to help them rewind a few minutes. There may be various reasons why the apps have different affordances for this feature. The less adjustable features, the simpler the apps will be for the users to understand. However, some users may want more options. Aside from these features, it is also possible to navigate the book via the progress line in the player. This line indicates the place in the book, and it is possible to use it to move back or forth in the book. However, this is more difficult to manoeuvrer and less precise than the rewind and fast forward feature.

Seven of the interview respondents often use the rewind feature. They may benefit from the fast forward feature as well although this is not mentioned in the same way in the interview material. All respondents employing the sleep timer at bedtime explain that they usually need to rewind a few minutes the next day, as they often fall asleep before the timer stops. A few respondents have also fallen asleep without setting a timer and have then had to rewind several hours.

Another common reason for rewinding is if respondents become distracted by something or find themselves daydreaming and are therefore not paying attention to the audiobook. P8 explains some of her reasons for using this feature:

I use the rewind often. Sometimes my mind drifts away and I forget to listen, or if I have fallen asleep, or even just taken out the rubbish to the bin and forgotten that the book was playing [on the speaker] inside. (P8)

As illustrated in this quote, it is possible to leave the room and forget to stop the audiobook when it is playing directly from the phone or through Bluetooth-speakers. When users are wearing headphones or earbuds, the book will continue to play in their ears wherever they go. However, it is still possible to get distracted when wearing headphones, as people may start talking to them, or they may need to focus on traffic when walking in the city. P10 explains that she will often rewind a few minutes just to make sure that she is truly following along in the story. This appears to be especially important if P10 is listening outside where she easily becomes distracted. The respondents want to be fully immersed in the book when reading for leisure, and do not wish to miss essential story elements. Rewinding is therefore an important yet taken for granted feature for many of them.

Discussion

This article notes which features are available in the player function of audiobook subscription service apps and highlights four reading practices afforded by these features. Several of the app features afford users more control over their interaction with the audiobook, compared with previous audiobook formats. Some also relate to established practices involving printed books.

Adjusting the speed allows for a new form of audiobook reading practice. Previously, changing the speed of an audiobook was difficult, if not impossible. In traditional reading by seeing, the reader is in control over the speed in which they engage with the book. The feature for adjusting the speed enable for audiobook users to decide the speed in which they want to comprehend the text when reading by listening. Previous research has found that there is a distinct difference between the enjoyment young people get from reading books they have chosen for themselves, and those assigned to them at school (e.g., Hedemark, 2021). This relates to findings in this study and explains why several respondents chose to increase the speed when reading by listening for school

The rewind and fast forward features also allow some user control over the audiobook. A printed book is possible to leaf through, for example to check a previous page or to see when the chapter ends. Such activities are complicated with an audiobook. However, rewinding makes it possible to go back if the listener has lost focus, or if they want to make sure they understood the meaning of a passage. This becomes an important feature as users often combine audiobook reading with other activities (Have and Pedersen, 2020; Hedemark, 2021), they may therefore get distracted at times.

Selecting a track can also be part of browsing practices, enabling users to jump between places in the text. Among the interview respondents, this feature was employed when switching between two book formats for the same title, choosing the most suitable format in the moment. This is an emerging reading practice which will be interesting to follow as it develops. However, the select track feature was described as confusing and imprecise by some respondents, as the change from chapter to track is not always clear. Numbering tracks in different ways from the chapters in the printed book is therefore problematic for users.

The sleep timer can be connected both to traditions of reading a book in bed or being read to at bedtime as a child. These are both established reading practices. Without a timer feature, audiobook users would need to make sure to stop the book as they started feeling sleepy, or else risk having the book playing all night. The timer therefore affords for audiobooks to be part of bedtime reading just as printed books or e-books. A difference is that someone reading by listening can fall asleep before the timer stops, which means that the content of the book changes from text they create meaning from, to noise to sleep to.

Although the three apps are similar in many ways, there are some differences regarding how users can adjust the features to suit their needs. This raises questions as to what the intention has been with these different features and what the general objective has been when designing the apps. One objective could be to make the apps easy to understand, which could explain some of the locked settings. With less adjustable settings there are fewer aspects for the user to figure out, compared to if there are more adaptable features. This however does not explain why some features are adjustable. A second objective could be to facilitate existing reading practices by designing features in the apps whose affordances enable those practices. However, this is reliant on designers being aware of user practices so as to not create hindrances within the apps instead. Finally, a third objective for the app developers could be to nudge the user into certain practices which may be beneficial to the subscription services themselves.

The economic model of the subscription services mean that users pay their subscription fee once a month, rather than for each book they read. As such, the company does not earn money when a user reads a book, rather every read book costs them money as they have to pay the publishing houses. However, it is still in the services interest that subscribers want to read the books on the platform. For instance, users on lower priced subscriptions who increase their reading will need to move over to premium subscriptions. Furthermore, the more the app is used, the more user data can be collected, such as which book titles are read, as well as when, where and how much subscribers listen (Zuboff, 2019). This can be combined with personal information users have provided themselves, subscribers are for example invited to write book reviews (Linkis, 2021). Even if user data is not sold on to other companies, as is common with social media platforms, this is information which can be applied to further develop the app. Moreover, it can be used to decide which content to buy, create and promote, and to improve algorithms for personal recommendations (Zuboff, 2019). These are all aspects which can make the service feel more relevant to the user. The more the app is part of the user’s everyday life, the more probable it is that they will continue to subscribe.

Conclusion

The aim was to explore features of the audiobook player in three subscription service apps, and how these were used by young audiobook listeners, in order to identify affordances of the features and how they enable or constrict audiobook reading practices. The article was based on an interview study with ten young Swedish users of the audiobook apps and a feature analysis of the player in the three apps performed by the author.

The results showed that while there were between 10 and 12 features in the player function in each app, four features were used the most by the respondents in the interview study. This can be of relevance to app developers as it highlights which features can be developed further to suit users. Furthermore, these findings show that new reading by listening practices are emerging in relation to these audiobook apps. Audiobook users can now control the speed in which they interact with the text. They can rewind and fast forward to browse, or to go back in the text if they want to re-read a passage. Readers now alternate between book formats, choosing the most suitable format for the moment. The feature for select track is occasionally useful for audiobook listeners in relation to this practice. Finally, the sleep timer enables audiobook reading at bedtime, as the timer ensures the book only plays for a set time.

About the author

Elisa Tattersall Wallin is a senior lecturer at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science, University of Borås. She received her PhD from SSLIS in 2022, and this article forms a part of her PhD research. She can be contacted at elisa.tattersall_wallin@hb.se

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank David Gunnarsson Lorentzen, Jan Nolin and Anna Lundh, who read and commented on different drafts of this article and discussed the design of the study with me, and Birgitta Wallin for HTML support. Thank you also to the interview respondents for their time and to Storytel, BookBeat and Nextory for allowing me to publish screenshots of their apps.

References

Note: A link from the title, or from "Internet Archive", is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Baron, N. (2015). Words onscreen: the fate of reading in a digital world. Oxford University Press.

- Berglund, K. (2021). Introducing the beststreamer: mapping nuances in digital book consumption at scale. Publishing Research Quarterly, 37(2), 135–151. https://doi-org.lib.costello.pub.hb.se/10.1007/s12109-021-09801-0

- Colbjørnsen, T. (2015). The accidental avant-garde: audiobook technologies and publishing strategies from cassette tapes to online streaming services. The Northern Light, 13(1), 83–103. https://doi.org/10.1386/nl.13.1.83_1

- Colbjørnsen, T. (2021). The streaming network: conceptualizing distribution economy, technology, and power in streaming media services. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(5), 1264–1287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520966911

- Dahlgren, S. (2021a, 6 October). BookBeat: Vi har ökat intäkterna med 39 procent under 2021. [BookBeat: We've grown revenue by 39 percent in 2021]. Boktugg. https://bit.ly/3TQCHZl. (Internet Archive)

- Dahlgren, S. (2021b, 6 October). Nextory: Vi ökade antalet betalande användare med 68 procent under Q3-2021. [Nextory: We increased the number of paying users by 68 percent in Q3-2021]. Boktugg. https://www.boktugg.se/2021/10/06/nextory-vi-okade-antalet-betalande-anvandare-med-68-procent-under-q3-2021/ (Internet Archive)

- Dahlgren, S. (2022, 10 January). Storytel fick 342 600 nya abonnenter under 2021 - ökar exlusivt innehåll. [Storytel gained 342,600 new subscribers in 2021 - increasing exclusive content]. Boktugg. https://www.boktugg.se/2022/01/10/storytel-fick-342-600-nya-abonnenter-under-2021-okar-exklusivt-innehall. (Internet Archive)

- Eriksson, M. & Johansson, A. (2017). Tracking gendered streams. Culture Unbound, 9(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.1792163

- Floegel, D. (2021). Labor, classification and production of culture on Netflix. Journal of Documentation, 77(1), 209–228. https://doi-org/10.1108/jd-06-2020-0108

- Fragoso, S., Rebs, R.R., & Barth, D.L. (2012). Interface affordances and social practices in online communication systems. In G. Tortora & S. Levialdi, (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces (AVI '12), Capri Island, Italy, May 21–25, 2012. (pp. 50–57). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2254556.2254569

- Gibson, J. J. (1977). The theory of affordances. In R. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting and knowing: toward an ecological psychology (pp.67–82). Erlbaum.

- Gunnarsson Lorentzen, D. (2016). Following tweets around: informetric methodology for the twittersphere. Valfrid. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hb:diva-9339

- Hallinan, B. & Stripas, T. (2016). Recommended for you: the Netflix prize and the production of algorithmic culture. New Media & Society, 18(1), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538646

- Have, I. & Pedersen, B.S. (2020). The audiobook circuit in digital publishing: voicing the silent revolution. New Media & Society, 22(3), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819863407

- Have, I. & Pedersen, B.S. (2021). Reading audiobooks. In L. Elleström. (Ed.), Beyond media borders, Volume 1 Intermedial Relations among Multimodal Media (pp.198–216). Palgrave Macmillan. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346223909_Reading_Audiobooks

- Hedemark, Å. (2021). Authenticity matters: the reading practices of Swedish young adults and their views of public libraries. New Review of Children's Literature and Librarianship, 26(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614541.2021.1971392

- Kaptelinin, V. & Nardi, B. (2012). Affordances in HCI: toward a mediated action perspective. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘12). Austin Texas, USA, May 5–10, 2012. (pp. 967–976). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2208541

- Linkis, T.S. (2021). Reading spaces: original audiobooks and mobile listening. Sound Effects, 10(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.7146/se.v10i1.124197

- Rivas-Garcia J.I. & Magadan-Diaz, M. (2022). An overview of the audiobook marketplace in Spain. Publishing Research Quarterly, 38(1), 168–179.

- Rogers, R. (2013). Digital methods. MIT Press.

- Rubery, M. (2016). The untold story of the talking book. Harvard University Press.

- Schatzki, T.R. (2005). Peripheral vision: the sites of organizations. Organization Studies, 26(3), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050876

- Schatzki, T. (2009). Timespace and the organization of social life. In E. Shove, F. Trentmann & RR. Wilk (Eds.), Time, consumption and everyday life: practice, materiality and culture (pp. 35–48). Berg.

- Tattersall Wallin, E. & Nolin, J. (2020). Time to read: exploring the timespaces of subscription-based audiobooks. New Media and Society, 22(3), 470–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819864691

- Tattersall Wallin, E. (2021). Reading by listening: conceptualising audiobook practices in the age of streaming subscription services. Journal of Documentation, 77(2), 432–448. https://doi-org/10.1108/JD-06-2020-0098

- Wallin, B., Carlsson, T. & Gunnarsson Lorentzen, D. (2021). Ljudboken tar nya tag: populär både via bibliotek och prenumerationstjänst. [The audiobook is taking off: popular both via libraries and subscription services]. In U. Andersson, A. Carlander, M. Grusell & P. Öhberg. (Eds), Ingen anledning till oro (?)(p.153–164). SOM-institutet. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hb:diva-25615

- Whitten, R. (2002). Growth of the audio publishing industry. Publishing Research Quarterly, 18(3), 3–10. https://doi-org/10.1007/s12109-002-0008-9

- Wikberg, E. (2021). Bokförsäljningsstatistiken, helåret 2020. Swedish Booksellers Association and Swedish Publishers’ Association. https://forlaggare.se.hemsida.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Bokforsaljningsstatistik_Helar_2020.pdf. (Internet Archive)

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for a human future and the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.