Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Oslo Metropolitan University, May 29 - June 1, 2022

‘Organizing professionalism’ - a discussion of library professionals’ roles and competences in co-creation processes

Camilla Moring and Trine Schreiber

Introduction. This paper investigates how co-creation may change the roles and relations between the library professional and citizens, and address what this development means to our understanding of what constitutes professionalism in the library profession as well as discuss the competences needed in order to be able to perform in this facilitating role.

Method. This is a conceptual paper discussing selected research on co-creation and professionalism. Three brief examples from public libraries in Norway and Denmark is presented to illustrate how public libraries can facilitate and/or engage themselves in co- creation processes.

Analysis. Research on co-creation and the role of professionals in co-creation processes creates together with Mirko Noordegraaf’s (2015) idea of ‘organizing professionalism’ an analytical lens for discussing how co-creation may change the competences needed for library professionals.

Results. The facilitating, relational and personal competences needed for library professionals in co-creation is discussed, and the importance of connections, dealing with conflicting logics and legitimising professional work is highlighted.

Conclusions. Organising professionalism provides another perspective on professionalism that brings to our attention, that parts of the knowledge needed in co-creation processes exists and develops in dispersed knowledge networks and therefore cannot only be developed as an individual competence.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/colis2213

Introduction

What is professionalism in post-industrial society and especially in public sector today? Many occupational workers want to call themselves professionals. One image of professionals have been that they deal with complex cases in an autonomous yet committed way. In public sector, however, there exists a pressure against sustaining professional control because it does not fit into the many attempts to restructure public sector as well as redefine public service delivery. Professionals are forced to organize their work in order to meet changed requirements and new values and accordingly have to change the ways they treat cases, prioritize cases, develop new cases or legitimize their work in new ways. Library professionals as service providers are no exception. They represent an institution, which ‘[…] although a remarkably durable institution, tends to have its raison d’etre continuously questioned’ (Audunson et al., 2020a, p. 10). Public libraries are constantly in need of legitimising themselves as public institutions which ‘results in evolving justifications linked to current trends which seek to explain why libraries exist, generally while convincing funding bodies of their legitimacy’ (ibid.). Hansson (2015) also states ‘…that public libraries have gone from being value-based professionally driven institutions to service institutions legitimized by the demands and perceived expectations of clients and users’ (p. 11). In line with this, one of the developments that have been emphasised is the role of libraries as ‘meeting places’ (Audunson, 2005; Audunson et al., 2020a; Audunson et al., 2020b). Public libraries as locally based institutions takes on the role as ‘community hubs’ (Johnston et al., 2021) in which citizens and other local actors can meet, discuss and work together to solve community based problems and challenges. This role entails that library professionals collaborate with the community in delivering the right kind of outreach services, activities and special events, and that they support community building as well as satisfy users, local communities, and national boards.

In this paper we will focus on one specific activity related to the library’s role as meeting place, namely the facilitation of co-creation processes. In short, the term co-creation refers to a joint effort among citizens and public sector professionals in the initiation, planning, design and/or implementation of public services (Brandsen et al., 2018). In literature on public administration the concept is often linked to new public governance where ‘interdependencies and collaboration between public, private, and non-profit actors are emphasised’ (Steen and Tuurnas, 2018, p. 81). In present public sector we find new public governance intertwined with other paradigms as e.g. new public management (Torfing et al., 2020), but taken in isolation new public governance implies that public institutions and professionals no longer only act as service providers, but also as facilitators of collaboration processes with citizens and the civil society, engaging them in the co-creation and development of public service. Citizens are hereby assigned more or less influence on service provision, and the traditional hierarchies is expected to be replaced by more horizontal relations that blurs the boarders between state, market and civil society, and also implies negotiations about responsibilities and management. Hence, how, by whom, and in what way co-creation-processes are initiated and managed in- between different actors will result in different types of co-creation.

Of particular interest to this paper is how co-creation might change the roles and relations between library professionals as service providers and citizens as service users, as well as how it entails changes in competences and the position of expert knowledge possessed by library professionals when ‘professional bases of legitimacy no longer are professional standards only but also organizational output and collaboration skills’ (Steen and Tuurnas, 2018, p.82). Hence, the overall question raised in this paper is what this development means to our understanding of what constitutes professionalism in the library profession?

In 1988 Andrew Abbott posed the assumption that it is not possible to define a profession once and for all (Abbott, 1988). Society changes, new technology emerge and professional repertoires will change accordingly. Twenty years later Mirko Noordegraaf (2007) continues this debate by claiming that the use of the word ´professionalism´ is to be seen as a symbolic act, i.e. an act representing a specific meaning and at the same time legitimising work practices. In other words, the definition of a profession, and what constitutes professionalism, is subject to negotiation. Therefore the aim of this paper is to discuss how co-creation processes may influence and change the way we understand the library professional. Similar to Johnston et al (2021) we think of library professionals as both educated librarians holding a diploma in librarianship as well as other employees in public libraries ‘...no matter educational background, with professional responsibility for developing and mediating library services to the public’. In the following we first define co-creation and briefly present three selected examples of co-creation in public libraries from Denmark and Norway. Then we introduce a typology of co-creation processes, and discuss the professional role and the competences needed to engage in these processes. In a next step we use Mirko Noordegraaf’s concept ‘organizing professionalism’ as an analytical lens for finally discussing how co-creation may impact and change the competences needed for library professionals.

Different types of co-creation processes

The concept co-creation needs an introduction as it share some similarities with the related term ‘co-production’. Both terms refer to some kind of collaboration between professional public service providers and citizens, and offer citizens the opportunity to actively engage in shaping services. However, there are also differences between the two concepts of importance to our understanding of co-creation:

Co-production is generally associated with services citizens receive during the implementation phase of the production cycle, whereas co-creation concerns services at a strategic level. In other words when citizens are involved in general planning of a service – perhaps even initiating it – then it is co-creation (Brandsen and Honingh, 2018, p. 13).

Co-creation is a strategic development tool where public and private actors (i.e. citizens/users, voluntary groups of citizens, civil society organisations, social enterprises or private corporations) collaborate in order to provide new and better solutions to shared problems and challenges. Professionals then engage in co-creation to develop plans or strategies and/or create new solutions in accordance with the needs of the local community ‘…through a constructive exchange of different kinds of knowledge, resources, competences and ideas that enhance the production of public value…’ (Torfing et al., 2020, p. 9). Hence, co-creation processes can be used to develop both core and complementary services as well as strategies for a library.

In a comparative study Johnston et al. (2021) found that the library’s role as community meeting place is relatively highly ranked in the Nordic countries when legitimising public libraries. Hence, to introduce some brief examples of different co-creation processes in public libraries three recent projects - two from Denmark (Madsen and Mikkelsen, 2016; Andersen and Espersen, 2017) and one from Norway (Stabell et al., 2020) - have been selected. The first example is a Norwegian public library in a small community that engaged the local community in the strategic development of the library’s role by focusing on the library’s contribution to “the good life”. Through workshops and user journeys the library identified several initiatives and activities where it could act as facilitator in collaboration with local initiators (Betten, 2020). Another example show how co-creation was used in planning library programming activities together with specific user groups in the community. In this case a Danish public library arranged an information meeting for refugees in the community together with a local resource person having the necessary language skills, and personal network, to facilitate such an event (Madsen and Mikkelsen, 2016). Finally, a third type of co-creation was used by a group of Danish public libraries in a joined effort to reach out to citizens that were not regular users of the libraries (e.g. elderly, refugees and vulnerable families). By engaging these groups of users in the development of activities and services of specific relevance to them, the libraries were able to extend their existing services and enhancing their role in the community (Andersen and Espersen, 2017). Although just used as illustrative examples the three projects indicates that the libraries formulate different aims and purposes for engaging citizens and other private actors in co-creation processes ranging from the development of core services and activities to support more overall strategic efforts.

A typology of co-creation

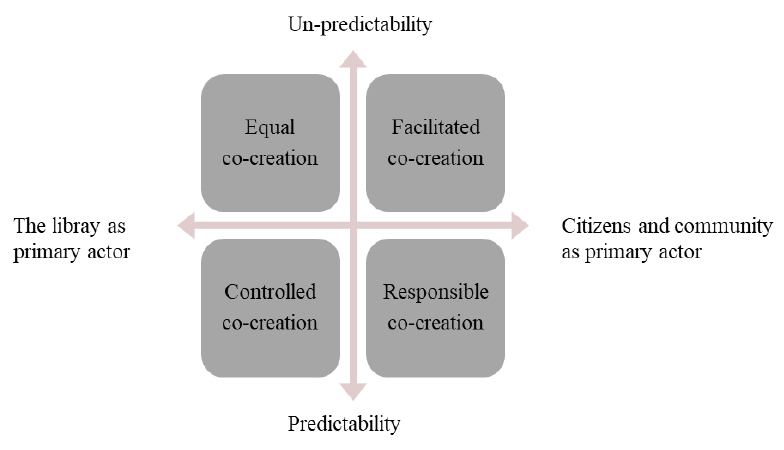

In co-creation processes the different actors - library professionals as well as citizens - can play different roles. Ulrich (2020) present a typology of co-creation processes that on the one hand focuses on the primary actor that drives the process, and on the other hand the management of the co-creation process i.e. to what extend the library professionals defines the purpose and process of co-creation, and hereby tries to predict and control its content and outcome. This is illustrated in Figure 1. On the horizontal axe we find the library as the primary actor and driver in the one end of the continuum, and the community and citizens in the other. On the vertical axe we find the degree of management and control with the process and hereby the predictability of its outcome. In the intersection of the two axes four different approaches to co-creation occurs.

In the controlled co-creation process the library/library professional define the content and outcome of the co-creation process, and the citizens only briefly contributes. This process mirrors to some extend the traditional role of the library professional as service provider and the citizen as service user or consumer. In the responsible co-creation process the library/library professional define the purpose of the process and is responsible for initiating an activity or event, but leave the effectuation and actual work to the citizens or other community actors. This type of co-creation is more likely to be described as a co-production process. In the upper right corner of the model is the equal co-creation process where the library/library professional still is the one who define the purpose of the process, but have not defined the outcome of it. This kind of co-creation is more like an invitation to collaborate on the development of library services and activities, and were the result or outcome of the process is unknown to both parties. Finally in the facilitated co-creation process citizens takes the initiatives, and the library then facilitate and offer different kinds of support in realising their ideas. It is still a collaboration but the library professional plays a more unobtrusive role. In three out of these four types of co-creation (i.e. the responsible, the equal and the facilitated co- creation) the library professional is positioned in a role that may require renewed competences and changes in the professional culture.

The role of professionals in co-creation processes

Recent research on co-creation addresses the various ways in which co-creation will change the relations between professionals, management, users and other stakeholders, and hereby transform and also challenge traditional professional roles in public sector. Co-creation involves all the different actors in complex interactions across public and private organisations and civil society. This requires professionals to act outgoing and to change their point of view from inside-out to outside-in (Ulrich and Stabell, 2020). Public institutions as e.g. libraries is no longer in the centre of their activities, but instead part of local networks juxtaposed to other actors, and therefore professionals is facing the need to develop ‘a new working culture that focuses on dialogue, curiosity and openness and sees professionals as mediators between administrators and citizens (Torfing et al., 2019, p.25). Accordingly the ability to engage in and develop relevant co-creation processes seems to depend on the development of at least three important competences within the library profession. The first is the competences relevant to the role as facilitator or process consultant. In all the co-creation processes mentioned above the library professional is initiating and/or facilitating the process. Instead of defining themselves in accordance to their educational background library professionals have to legitimise themselves as skilled facilitators establishing and securing an environment that supports co-creation in a productive way. This may challenge the position of being a professional expert possessing expert knowledge. Also the professional-client relation changes from a one-directional relationship to a collaborative one based on the equality of the user and the professional (Steen and Tuurnas 2018). As a barrier to this, public employees who strongly identify with their role as professional and expert may find great difficulties in identifying and mobilising the resources of users and civil actors that is an integral part of their new role as facilitators (Torfing et al., 2019).

Strongly connected to the role as facilitator is the relational competences needed in order to be able to work with new hybrid formats of organising and knowledge production. The ability to connect to, as well as bridging between, actors is key: ‘Overall, competences required from the professionals are relational, focussing on the ability to facilitate and mobilise others, rather than technical skills or substantive knowledge of the subject at hand’ (Steen and Tuurnas, 2018, p.83). Ulrich and Stabell (2020) distinguish between co-creation as a methodological competence that can be applied in specific projects, and as a relational competence integrated in the daily work and in the ways that professionals reach out and connects to the community and its local actors. Finally, also personal skills and competences seems to become more important as ‘the shift from traditional bureaucrat to professional service provider deskills and reskills the public servant, for example, by shifting from knowledge and training acquired in specialized fields to required “personality skills”’ (Pors, 2015, p.178). Although this is a somewhat open category research in the field refers to public employees needing to possess individual attributes such as open-mindedness and empathy (e.g. Steen and Tuurnas, 2018).

But what is the wider implications of these changes to the library profession and how does co-creation processes impact the role of the library professional? In the following sections we will first present Mirko Noordegraaf’s idea of organising professionalism and then use it as an analytical lens to discuss how co-creation may change the competences needed for library professionals.

Organising professionalism

Noordegraaf describes how societies today resist clear definitions of concepts such as profession and professionalism caused by e.g. requirements of flexibility, specialisation, satisfied consumers, cost control etc. (Noordegraaf 2007; 2015; 2016). Public institutional power is challenged and destabilised, and occupational boundaries are changed. This creates a situation which at the same time call for professional practices and weaken strong professional practices (Noordegraaf, 2007, p.770). Based on these premises Noordegraaf discuss how to reinterpret professionalism, and it is his opinion that the definition of the concept profession must be relative to time and space. To understand today’s professionalism he rejects concepts such as purified professionalism or situated professionalism. The first one highlights occupational control and the second one organisational control as central parts of professionalism (ibid, p.775). Neither of these conceptions can explain the complicated processes in societies today. Instead, and based on empirical insights about changes in society, he develops a new understanding of public professionalism that includes, among others, collaborative and relational elements. First Noordegraaf (2007) suggests to substitute both purified and situated professionalism with the concept ´hybridized professionalism’. Using this concept he combines professionalism (meaning professional autonomy, authority based on knowledge and trust, and with a professional value such as quality) with managerialism understood as general quality standards like timeliness, speed, and efficiency (Noordegraaf, 2015, p.188). The outcome is a conceptualisation of professionalism responding to the situations where occupational borders are no longer clearly defined, and where there does not necessarily exist any predefined knowledge to be applied to specific cases (Noordegraaf, 2007, p.775). However, the idea of a hybridised professionalism involves a relational image of professionalism. He explains it in this way: ´Professionals know how to operate in organized, interdisciplinary settings …; they know that cases, clients, costs, and capacities are interrelated´ (ibid, p. 775). Contrary to previous understandings of professions, professionalism is no longer a question about controlling content, but instead about content of control: […] ´it is about controlling the meaning of control, organizing, and professionalism´ (ibid, p.775).

In hybrid professionalism professional action can be ´… positioned within managed and organized surroundings that both respect and restrain professional spaces´ (Noordegraaf, 2015, p.192). In this sense, hybridised professionalism seems to presuppose relational competences with the professionals. They simply need to know how their tasks are interrelated to the work of others.

Later Noordegraaf (2015) describes how the relational image of professionalism has changed, and explains it by referring to external and societal factors such as ´globalization and corporatization´, ´transnational organizational forms´ as well as ´economic and social, as well as cultural, technological, and demographic shifts´ (ibid, p.196). Already in 2007 Noordegraaf found new public management to be an important element in describing hybrid professionalism, and in 2015 he still finds it to be a key factor influencing professional work. In hybrid professionalism, it was important to manage professional work, i.e. professionals and the organisational context were interrelated, but now professionals must go beyond hybridity and take responsibility for co-organising processes with external parts like stakeholders, external teams and other organisations. He defines ´beyond hybridity´ as ´…new service logics in which organizing becomes part of professional work´ (Noordegraaf, 2015, p. 198). Hence organising ´… becomes an intricate part of professional work´ (ibid, p.197), and professional work has to be organised within professional practices themselves. Nordegraaf label this new logic for ‘organizing professionalism’ where the term organising refers to the professional work in at least three ways. Firstly, ´organizing work is a matter of changing ways to treat cases´ (Noordegraaf, 2015, p.197). Professionals meet new expectations from clients, they have to use new technologies, collaborate with other professionals or organisations etc., and at the same time they have to change the way the work is organised: ´organizing work is a matter of changing ways to treat case treatment´ (ibid, p.197). Secondly, Noordegraaf states that the traditional case-based approaches are under pressure caused by e.g. the increasing demand for efficiency in public organizations. Professionals have to organise their work in new ways to deal with multiple cases in the same time. They have to be able to prioritise cases as well as their treatment, but also to ´establish collaborative cultures´ (ibid, p.198). Thirdly, ´organizing work becomes a second order matter of changing ways to treat the ways in which the treatment of case treatment is treated´ (ibid, p.197). At this point external organisations and private actors such as citizens, clients, and other stakeholders show their influence. The external environment will watch, discuss and maybe criticise the ways in which professionals treat cases as well as treat case treatment. Noordegraaf here raises important questions about how it may influence the professional: ‘are professionals able to meet stakeholders’ wishes? Are professionals able to detect risks before they lead to errors or failure? Are they able to take appropriate action?’ (ibid., p. 197). Hence professionals have to organise their work in ways that make them able to meet external requirements, address public debates, and anticipate critique. He label this as ´case treatment in context´ were ‘active coping with stakeholders, risks, and outside pressures becomes embedded within professional practices’ (ibid, p.198). Thus, professionals do not only treat cases individually; they work together and collaborate with other professionals, as well as clients and other stakeholders and becomes responsible for co-organising various processes, and as part of this, they also have to ensure that their work gains legitimacy in the local community, and in society.

If we look at these three ways of case treatment, the first ‘ways to treat cases’ is very similar to Donald A. Schön’s description of ´The reflective practitioner´ (1992). Schön states that professionals seems to manage and solve ‘wicked’ problems appearing in unexpected situations by using reflection-in-action. Hence, on this first level of case treatment the relational and collaborative elements is seen as part of the problem-situation to which the professional must find a solution. To some extend this is also the case when looking at the second level, the ways to treat case treatment, but here the work on establishing collaborative cultures is highlighted although at the same time it is still articulated as a specific, and delimited type of task, possible to separate from other parts of the professional work. Then on the third level in which the treatment of case treatment is treated all kinds of autonomy of the professionals has disappeared, and instead they have to manage their work in a landscape of conflicting logics, not only inside the organisation (as in hybrid professionalism), but also across different organisations and stakeholders. Organising professionalism do first and foremost differ from hybrid professionalism by highlighting the task of mediating between conflicting logics based on at least two different organisations. Noordegraaf describes this as dealing ´with multiple cases in demanding environments´ (2015, p.200) and argues that ´instead of isolating professional practices from outside worlds, professionalism becomes connective´ (ibid, p.201). However, at the same time he assures us that:

Professionals are still experts, but they are able to link their expertise to (1) other professionals and their expertise, (2) other actors in organizational settings, including managers and staff, (3) clients and citizens, (4) external actors, that have direct stakes in the services rendered, and (5) outside actors that have indirect stakes, such as journalists, inspectorates and policy makers (Noordegraaf, 2015, p.201).

As already mentioned, the value of this kind of professionalism strongly emphasises not only connections but also legitimacy. So to summarise, when connections are made between professionals and others, the professionals still have to be able to define their work as a kind of expertise, but they also have to perform and articulate it in a way that can be identified as legitimate by others. This relates to Carr’s (2010) point that expertise is not only something one has but something one does.

Discussion

When libraries involves in co-creation processes the development of facilitating competences and relationship building becomes an important aspect of the library professional’s work (Andersen & Espersen, 2017; Evjen & Vold, 2018; Ulrich & Stabell, 2020). Regardless the usefulness of these insights, Noordegraaf’s idea of organising professionalism suggest that it is not only a question of the individual developing specific skills or competences, but it is also about being able to develop them in accordance to others, internally as well as externally. This seems to be the case independently of the type of co-creation (i.e. controlled, responsible, equal or facilitated co-creation processes) that the library professional may engage in. This means, that although professionals are still experts, their expertise becomes dynamic and linked to others. They do not only possess an independent and specific kind of expertise and core competences which e.g. has been developed through education that together creates the fundament for professional action and performance (Noordegraaf, 2015). Instead professionals will develop their expertise in relation to others. This flips the traditional understanding of professionals applying their expertise (or knowledge-base) on specific problems or cases, towards an understanding of professionals that by engaging in solving problems and cases through co-creation develop their expertise. So, when the library professionals in the Norwegian project states, that they experience co-creation as a relational competence integrated in the daily work, and in the ways that they can reach out and connect to the community (Ulrich and Stabell, 2020), this is important to address, not only as a new competence required, but as a new way to understand professional expertise. The expertise of library professionals will change accordingly to the many different collaborative situations they will take part in. Focusing on co-creation processes the development of expertise may depend on whether we talk about controlled, responsible, equal or facilitated co-creation. Here, the concept of co-creation itself indicates that library professionals will experience various kinds of expertise related to who defines the purpose of the co-creation process, and who drives, as well as controls, the process.

However, as Noordegraaf states ‘connective professionalism is no smooth professionalism’ (2015, p. 202), and this radical shift in the understanding of expertise and professionalism may in the longer perspective challenge the library professionals and their identity. It can be difficult for professionals to adopt to new roles: ‘…the sedimented roles and identities of public and private actors are often rather difficult to transform. It is painful to redefine one’s identity and adopt a new role, and therefore, social actors often cling to their old role perception’ (Torfing et al., 2019, p. 19). For instance, reservation or even resistance to users’ ideas can express reluctance to modify professional roles or professional identities (Jenhaug, 2020) and become a barrier in co-creation processes. As Noordegraaf (2015) points out, professionals today have to organize their work in ways that make them able to meet external needs and requirements, and also to anticipate possible critique. He also emphasises that tensions and contradictions will be all more present in many situations involving professionals´ work. However, the challenge to the professionals is to make these tensions productive, but as part of making tensions and contradictions productive professionals have to legitimise their work, actions and decisions. Therefore, following the idea of organising professionalism, library professionals do continuously need to argue for the legitimacy of their actions and their expertise. As Noordegraaf states: ‘this is not important because it is nice to organize. It is important because societal conditions generate new needs and demands, which can only be met by more organized, that is, interrelated, responsible and stakeholder-based professional action’ (Noordegraaf 2015, p. 202). Also Steen and Tuurnas highlights legitimising as an important element in co-creation: ‘… a fundamental question is also the changing legitimacy of professionalism in an environment where knowledge structures becomes ever more dispersed’ (Steen and Tuurnas, 2018, p. 88), and legitimising work seems to be relevant in all type of co- creation processes. However, we have to pose the question what it means to legitimise professional work, actions and decisions? First and foremost professional work (or case treatment) need to be performed in a way where actions and decisions are perceived as appropriate and socially acceptable. Legitimacy has been defined as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values beliefs and definitions’ (Suchman, 1995, p.574). If we take this definition as our pivotal point for the discussion, it becomes clear that legitimising actions and decisions cannot be turned into an individual competence. Legitimising is a social process that are negotiated in a network of various people and across many different contexts. It is not a simple communicative competence, but a process involving both library professionals as well as library users, local citizens and organisations, other stakeholders, politicians etc. Therefore the idea about organising professionalism provide us with another perspective that brings to our attention that not all of the knowledge and expertise needed in co-creation processes can be developed as an individual competence. Instead this knowledge exists and develops in dynamic, diverse and dispersed knowledge network.

Conclusion

In this paper we have discussed how co-creation may change our understanding of what constitutes professionalism in the library profession, and how it may change the roles and relations between library professionals, citizens and other private actors in the local community, but also how it may change the competences needed for library professionals in order to be able to facilitate co-creation processes. Through our analysis of co-creation processes and organising professionalism, we have identified three areas of development of importance in this regard. Firstly, public libraries are increasingly turning their attention outwards, and towards their role as meeting places. As public organisations they are subject to changing public management paradigms e.g. new public governance, that put emphasise on public organisations and professionals’ collaboration with citizens and civil society as a whole. One way that public libraries have adapted to this development is by using co-creation to involve the local community in strategy- and service development processes. Secondly, we found that engaging in co-creation processes may create new roles for library professionals when being involved in complex interactions across traditional boundaries. Hence, co-creation requires facilitating and relational competences, and focuses on the professionals’ ability to create connections. Thirdly, Noordegraaf’s (2015) idea of organising professionalism emphasises not only the importance of connections, but also the legitimacy in professional work. When connections are made between professionals and other professionals or citizens, they need to be able to define their work as a kind of expertise as well as to perform and articulate it in a way, which can be identified as legitimate by others. Also library professionals do continuously need to argue for the legitimacy of their institution, their work, their actions and their expertise. When library professionals engage in co-creation processes this is also the case, but legitimising cannot be turned into an individual competence as it is established in a network of internal and external actors, and across different contexts inside and outside the library. Finally, and as mentioned in the introduction, what constitutes professionalism is subject to negotiation. Based on this assumption it seems reasonable to believe, that when libraries e.g. engage in co-creation, various changes in the roles and competences of the library professionals will follow, and that such developments will necessitate further discussions about what constitutes library professionalism in the future.

About the authors

Camilla Moring is Associate Professor at the Department of Communication, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. She holds a PhD in Library and Information Science. Her research focuses on how technology and digitalisation transforms organisations and work practices in various contexts. She can be contacted at camilla.moring@hum.ku.dk

Trine Schreiber is Associate Professor at the Department of Communication, University of Copenhagen, Denmark. She received her PhD from Umeå University, Sweden. Her research interests are professionalism, professional work in libraries, practice theory, and actor-network-theory. She can be contacted at trine.schreiber@hum.ku.dk

References

- Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions. An essay on the division of expert labor. The University of Chicago Press.

- Andersen, L.L., & Espersen H.H. (2017). Bibliotekers arbejde med samproduktion og samskabelse [Libraries engaging in co-production and co-creation]. In Laskie, C. (ed.). Biblioteksdidaktik [Library didactics] (pp. 127-153). Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Audunson, R. (2005). The public library as a meeting-place in a multicultural and digital context. Journal of Documentation, 61(3), 429-441. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410510598562

- Audunson, R. et al. (2020a). Introduction. Physical places and virtual spaces: libraries, archives and museums in a digital age. In Audunson, R. et al. (eds.). Libraries, archives and museums as democratic spaces in a digital age (pp. 1-22). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110636628

- Audunson, R. et al. (2020b). LAM professionals and the public sphere. In Audunson, R. et al. (eds.). Libraries, archives and museums as democratic spaces in a digital age (pp. 165-183). De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110636628

- Betten, J. (2020). Det gode liv i Nesseby [The good life in Nesseby]. In Biblioteket som samskaper: erfaringer med biblioteket som samfunnsutvikler [The library as co-creator: experiences with the library as community developer]. (pp. 32-35). https://bibliotekutvikling.no/boker/biblioteket-som-samskaper/

- Brandsen, T.et al. (2018). Co-creation and co-production in public services. Urgent issues in practice and research. In Brandsen, T.; Steen, T. and Verschuere, B. (eds.). Co-production and co-creation: engaging citizens in public services (pp. 3-8). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315204956

- Brandsen, T. & Honingh, M. (2018). Definitions of co-production and co-creation. In Brandsen, T.; Steen, T. and Verschuere, B. (eds.). Co-production and co-creation: engaging citizens in public services (pp. 9-16). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315204956

- Carr, E. S. (2010). Enactment of expertise. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 17-32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104948

- Evjen, S. & Vold, T. (2018). "It's all about relations"- an investigation into the youth librarian’s role and proficiency. Nordisk Tidsskrift for informationsvidenskab og kulturformidling, 7(3), 59-73. https://doi.org/10.7146/ntik.v7i3.111487

- Hansson, J. (2015). Documentality and legitimacy in future libraries – an analytical framework for initiated speculation. New Library World, 116(1/2), 4-14. https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-05-2014-0046

- Jenhaug L.M. (2020). Employees’ resistance to users’ ideas in public service innovation. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 79, 444–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12415

- Johnston, J. et al. (2021). Public librarians’ perception of their professional role in supporting the public sphere: a multi-country comparison. Journal of Documentation, vol. ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-09-2021-0178

- Madsen, N.G & Mikkelsen, E. (2016). Samskabelse – involvering og aktivering af borgere og lokalsamfund [Co-creation – involving and activating users and local community]. https://www.nisgmadsen.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/samskabelse_artikel_1.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20220513124938/https://www.nisgmadsen.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/samskabelse_artikel_1.pdf)

- Noordegraaf, M. (2007). From “pure” to “hybrid” professionalism. Present-day professionalism in ambiguous public domains. Administration & Society, 39(6), 761-785. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399707304434

- Noordegraaf, M. (2015). Hybrid professionalism and beyond: (New) forms of public professionalism in changing organizational and societal contexts. Journal of Professions and Organizations, 2015(2), 187-206. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/jov002

- Noordegraaf, M. (2016). Reconfiguring professional work: Changing forms of professionalism in public services. Administration & Society, 48(7), 783-810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399713509242

- Pors, A.S. (2015). Becoming digital – passages to service in the digitized bureaucracy. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 4(2), 177-192. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-08-2014-0031

- Schön, D.A. (1992). The reflective practitioner. How professionals think in action. Ashgate Publishing Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473

- Steen, T. & Tuurnas, S. (2018).The roles of the professional in co-production and co-creation processes. In Brandsen, T.; Steen, T. and Verschuere, B. (eds.). Co-production and co-creation: engaging citizens in public services (pp. 80-92). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315204956

- Stabell, Ø. et al. (2020). Biblioteket som samskaper: erfaringer med biblioteket som samfunnsutvikler [The library as co-creator: experiences with the library as community developer]. Available at https://bibliotekutvikling.no/boker/biblioteket-som-samskaper/

- Suchman, Mark C. 1995. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331

- Torfing, J. et al. (2019). Transforming the public sector into an arena for co-creation: Barriers, drivers, benefits and ways forward. Administration & Society, 51(5), 795-825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716680057

- Torfing, J. et al. (2020). Public Governance Paradigms - competing and co-existing. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

- Ulrich, J. (2020). Samskabelse som greb i biblioteksudvikling [Co-creation as part of library development]. In Biblioteket som samskaper: erfaringer med biblioteket som samfunnsutvikler [The library as co-creator: experiences with the library as community developer]. (pp. 32-35). https://bibliotekutvikling.no/boker/biblioteket-som-samskaper/

- Ulrich, J. & Stabell, Ø. (2020). Verdifulle erfaringer med samskaping [Valuable experiences with co-creation]. In Biblioteket som samskaper: erfaringer med biblioteket som samfunnsutvikler [The library as co-creator: experiences with the library as community developer]. (pp. 61-66). https://bibliotekutvikling.no/boker/biblioteket-som-samskaper/