The investigation of information use and users' needs as a basis for training programmes

T.D. Wilson, University of Sheffield

1 Introduction

User training programmes commonly take two main forms: a) introduction to the resources of a specific library, with instruction on how to gain access to these resources; and b) introduction to the total bibliographical apparatus of a given subject field. In neither case does much attention appear to be paid to users' needs as a basis for designing these programmes. This is a curious situation when there is a comparatively large amount of information available on how workers and students in different disciplines seek information.

This paper is concerned with a) the definition of user groups and information needs; b) the functions of information needs investigations; c) methods of investigation; d) the bases of an investigation; and e) an illustrative case-study. In general a note-like form of presentation is used in order to keep within the space limitations set.

2. User groups

It may seem elementary to say that before an investigation can be undertaken there needs to be some definition of the target group, but the idea of 'the user' can be a trap for the unwary. It conflates into a single concept a wide range of individual behaviour and, to a certain extent, it may be a statistical construct with no correspondence in reality.

Useful sets of categories have been devised for defining groups of interest: for example, Havelock (1973) writes of four subsystems of the 'knowledge macrosystem':

- research subsystems,

- development subsystems,

- practice subsystems, and

- consumption subsystems.

Within these he identifies specific sub-groups; for example, within the practice subsystem there are;

- the practice professions,

- the product organizations, and

- the service organizations.

Clearly, the same kind of analysis can be applied to fields other than science and technology.

3. Information needs

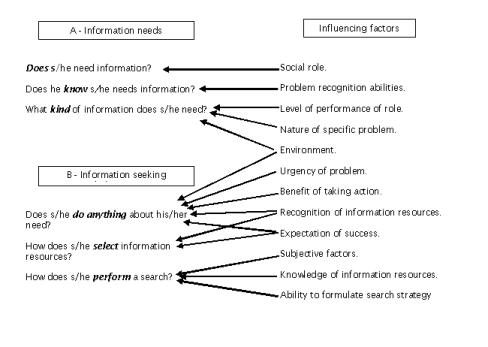

The two concepts 'information needs' and 'information-seeking behaviour' have often been confused in research and writing. There is a difference and it can be illustrated by reference to the kinds of questions to which the two concepts give rise. (Figure 1 below)

Figure 1: Information needs and information seeking behaviour

Finding out about information needs involves asking:

- Does this person or group need information?

- Does he know he needs information?

- What kind of information does he need?

- What factors are likely to influence needs?

These questions are difficult to answer because they imply that the person who needs information may not have defined that need and so may find it difficult to think of information in the same terms as the researcher. Whether one pursues questions of this kind depends upon how well the target group is defined and whether it is really necessary to have answers to such questions.

In other words an interest can be claimed in only those who have defined information needs for themselves. Attention can then be given to information-seeking behaviour.

Finding out about information-seeking behaviour involves asking:

- What does he do about his need?

- How does he select information resources?

- How does he carry out a search for information?

- What factors are likely to affect this behaviour?

This is the area that we are usually concerned with if we are seeking information to guide the development of user-training programmes. In effect, through the experience of librarians and information workers, the first set of questions has been asked and answered at the commonsense level of understanding. Through this level of understanding the opinion is formed that some training is necessary and that some additional information is necessary before such training can be planned.

4 . The functions of an investigation relative to user training.

The function of information needs (or information-seeking behaviour) investigations relative to user education programmes is to help to provide answers to the basic questions which the designer of such programmes needs to ask:

- For WHOM is the training intended? A user needs study can help in defining the target group and in drawing attention to subgroups with special needs. For example, a study by Törnudd (1959) of Scandinavian research and development workers revealed that those working in research institutes were less able to keep up with new developments in their field than their colleagues in universities or in industry. This suggests that training directed at that sub-group might have most impact.

- WHY is training required? A user needs investigation can provide or support arguments for: the introduction of training programmes by showing if the extent of need and, by comparison between informed and ill-informed groups, by suggesting the general benefits that might result from training.

- WHAT is the training programme intended to accomplish? User needs investigations can help to set realistic objectives for a training programme by helping to identify precise areas in which knowledge of information sources or information-seeking procedures is lacking. Objectives set on this basis can be defended much more strongly in discussion with agencies which may be providing the funds for a training programme.

- WHERE should the training take place? A consideration of the earlier comments on user groups will lead to the realization that different locations may need to be considered for different user groups. For some groups with a high awareness of information needs a national or regional course may be possible; for groups with a lower level of awareness it may be necessary to implement courses within individual organizations.

- WHAT training methods should be used? The deeper understanding of the user group's needs attained through an investigation can lead to a better appreciation of what instructional methods are likely to have most success.

- WHEN should training take place? An understanding of work schedules and cycles will enable training to be fitted into the normal activities of the target group with maximum effectiveness.

Clearly, it cannot be claimed that all of these questions can be answered at one and the same time by a single investigation but, if one bears in mind that they are questions for which some input from the users is necessary, then all stages of an investigation may help to provide parts of the answers.

5. Methods of investigation

There is no space here to give an extensive account of the range of investigative methods which can be used to study users' needs or their information-seeking behaviour. In any event the literature of sociological j research methods is very extensive and in the field of information use there are many examples of the use of the most common methods. For information on these reference can be made to the Annual Review of Information Science and Technology which in all but the present volume has a chapter on users needs. Older reviews which are still valid but difficult to obtain are those by the Bureau of Applied Social Research, Columbia University (1960) and by Paisley (1965). What I shall try to do, therefore, is to make some general remarks on the categories of methods and on factors to take into account in choosing methods.

Investigative methods in sociological research (and I take the study of information users to be within that field) can be divided into two broad categories: quantitative methods and qualitative methods. In recent years some sociologists have become disenchanted with quantitative methods and have turned to qualitative methods (sometimes called 'field research') to obtain data. Conflict has arisen within the field over the nature and purpose of research; quantitative methods have come to be associated with the 'positivist' or 'scientistic' approach to social research, qualitative methods with the 'phenomenological' approach which is concerned with understanding human behaviour from the point of view of the subject's own frame of reference. In my opinion both approaches have their place in user research and I have given the issue some space here only because you need to be aware of the distinction when you approach sociologists and research methodologists for guidance.

The two broad types of methods can be subdivided as follows:

| Quantitative methods |

|---|

|

- self-completed questionnaires, distributed by mail or in some other manner; - interviewing, using highly structured interview schedules - experiment (loosely used, in the sense of monitored innovations in information service delivery) - data collection from records of activities, e.g. library issue records. |

| Qualitative methods |

| -observation, sometimes divided into 'participant' and 'non-participant' observation; -analysis of personal documents, such as diaries, letters, and autobiographies, and of 'official' documents such as syllabuses, job descriptions, Internal organizational policy documents; -unstructured, open-ended interviews. |

The first point to be made in relation to the choice of methods is that they are not necessarily alternatives: circumstances may dictate that either a specific method must be used, or that a combination of methods must be used. For example, if you need to obtain information on, say, engineers throughout a country and funds are limited then probably the only method to adopt will be the mail questionnaire. If you are interested in a smaller population and the aims of the study are very well defined it may be desirable to use a combination of methods.

The second point is one that impinges upon the first; the method you use must depend upon what you want to know. Zelditch identifies three 'primary' methods and, in the Figure below he indicates which method is best for the kind of information the investigator is trying to obtain.

| Information types | Methods of obtaining information | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enumerations and samples | Participant observation | Interviewing informants | |

| Frequency distributions | Prototype and best form | Usually inadequate and inefficient | Often, but not always, inadequate. Efficient when adequate. |

| Incidents, histories | Not adequate by itself - not efficient | Prototype and best form | Adequate with precautions - efficient |

| Institutionalised norms and statuses | Adequate but inefficient | Adequate, but inefficient, except for universalised norms | Most efficient and hence best form |

The term qualitative is somewhat misleading, since, clearly, the methods subsumed under the term can be used to produce quantitative data. The term is used to indicate those methods of research which enable the researcher to get closer to the sources of data , and thereby enable him to take into account the subject's own perceptions of the problem under investigation. Advocates of these methods claim that quantitative methods cannot be used for this purpose and that they reflect concern with a natural science model which is inappropriate for social phenomena.

The criteria used by Zelditch to define the 'goodness' of a method are;

- informational adequacy: meaning accuracy, precision and completeness of data; and

- efficiency: meaning cost per added input of information.

Thirdly, the importance of the method of data collection should not be overemphasized at the expense of the logical definition of the categories of data that are being sought. This point is strongly emphasized by the report of the Bureau of Applied Social Research referred to above. Table 2 below is derived from that report:

| A - exposure to channels of communication |

|---|

|

- delineation of units of information-receiving behaviour - exposure vs. non-exposure? (e.g. Has he read a given journal at all?) - number of acts? (e.g. How often has he read it?) - time consumed; (e.g. How many minutes has he devoted to it?) - messages received? (e.g. How many facts has ha learned from it?) |

| B - the purpose or function of exposure |

|

- ways of classifying functions: - by the scientist's future activities; - by the type of message; - by the place of the message in the course of the scientist's total information-receiving activity. |

Clearly, in the case of a study directed towards the training of users, the extent to which questions on these two types of data will need to be adapted to the purpose of the study will be a matter for careful consideration.

Finally, it cannot be emphasized too strongly that the conduct of user needs investigations is a skilled task, requiring expert guidance if it is to be carried out by amateurs in the field of social research methods. Unless such guidance is available simple errors may be made which will invalidate the result of the investigation and, if the study is part of a larger effort, such as a national programme of research this may prejudice the results of that effort. The areas within an investigation which may affect reliability and comparability include:

- definition of the population or target group;

- the use of appropriate sampling methods;

- adequate definition of the categories of data being sought;

- choice of analytical procedures.

6. Bases of an investigation into users' needs relative to user training

- any investigation should have regard to the 'information environment' surrounding members of the target group, i.e., the library and information resources actually available, rather than those theoretically available;

- the corollary to this is that any study should be preceded or accompanied by a survey of available resources and their accessibility;

- any investigation should have regard to the existing modes and levels of user training and the extent to which they have been used by members of the target group;

- any investigation should have careful pre-definition of the geographical, organizational and subject discipline boundaries of the targetgroup or groups as this will influence the conduct of the study;

-

the aims and limits of the investigation require careful definition: such questions should be asked as:

- Is the study intended to reveal users' attitudes towards information or to show how they use given resources?

- Is the study intended to guide training policy locally or more widely?

- Have any previous studies been carried out on similar target groups and, if so, do they direct attention to particular problems and issues?

- If the study is a regional or country-wide one, are the different areas or organizations comparable?

- and so on;

-

ideally, then, a total programme requires:

- an analysis of needs in so far as they can be inferred from documentary sources (such as syllabuses in the case of students or official documents such as job descriptions in the case of other groups; from discussions with key individuals and as they are stated by members of the target group;

- an investigation into the present level of understanding of information sources and their use;

- an investigation into the present pattern of use of library resources and services;

- a study of the normal work behaviour or the target group to discover how far this behaviour allows for information use

- where feasible, a study of the use of services offered on an experimental basis;

- a study of the efficacy of different methods of user training.

Naturally, not all of these activities are embodied in all users' needs investigations but in any total programme for a given country or region they should be covered at some time.

7. Case studies

A. The Hamline University Project (Mavor and Vaughan 1974)

This project is particularly interesting for its integration of a) a users' needs study; b) the employment of information specialists in a university setting; c) instruction in the use of bibliographic rescurces and in searching procedures; d) assistance to faculty in the choice of reading for courses; e) improving the system of documentary provision; and f) the ongoing evaluation of the whole system.

There is insufficient space here for a full description of the project but the procedures for the assessment of users' needs are of particular interest, The academic course was selected as the unit of analysis and several interviews were held with the faculty member responsible for each course to determine the 'tasks'associated with the course for both the faculty member and the student. An interview guide was evolved for this part of the study and this covered such topics as; objectives of the course, tuition methods used, selection of topics to be covered, selection of reading material and audiovisual aids, and so on.

Following this analysis of tasks further interview sessions were conducted throughout the course to determine the information needs associated with each course tank. These sessions provided the information specialist with a basic understanding of information needs to enable him to deliver effective information services to the faculty member.

Procedures for assessing the needs of students followed a similar pattern of interviews to establish such facts as existing subject background, the time frame in which the material was needed, and the type and level of material best suited to the need. In addition the information specialist spent some time on each course in actual class sessions.

An integral part of the subject specialists' work was teaching:

'...suggesting bibliographic tools, providing guidance in the use of these tools, and aiding in the final screening and selection of material to be ordered.'

[Note: I imagine that this report is now almost unobtainable, but it reports what I believe to be the most imaginative study of what would now be called an 'information literacy' programme that has ever been undertaken. TDW 2006]

B. A study of some Open University courses and related students' needs

Table 3 below sets out the stages and methods used at each stage now being carried out in three regions of the Open University in relation to four third-level courses which require the student to gain access to specialized sources of information. The ultimate aims of the project are:

- to help OU course teams to produce realistic reading lists for students;

- to assist regional tutorial staff in giving - guidance to students on the availability of resources;

- to provide guidelines for the possible preparation of teaching packages for these courses specifically devoted to finding and using specialised information resources.

Thus, providing guidance on information use is one of the principal aims of the research.

| Questions | Methods |

|---|---|

| Pre-survey stage | |

| 1) what are the general course objectives? | Analysis of course handbooks and teaching units |

| 2) What library/information resources are needed to help students attain objectives? a) explicit and b) implicit. | Identification of libraries and other information sources and their mapping |

| 3) What resources are accessible to students in their areas? | |

| Survey stage | |

| 3) - same question | |

| 4) To what extent are available resources known to students? | Creation of a 'test file' of items from reading lists, etc. and checking in selected libraries. |

| 5) To what extent are they used? | Interviews and mail questionnaires. |

| 6) Which services are used? | |

| 7) With what success? | |

| 8) What obstacles are there to use? | |

| Post-survey stage | |

| 9) What can be done to overcome obstacles and problems? - by course teams, - by tutors, - by students, - by regional offices, - by librarians. | Analysis of data from preceding stages. Further interviews or discussions with interested parties. |

[Note: This was a study undertaken partly by myself, in association with the Leeds Regional Office of the OU. Part of the study was reported in Wilson, T.D. (1978) Learning at a distance and library use. Libri, 28, 270-282 TDW 2006]

8. Conclusion

By way of conclusion it seems worthwhile to make two very general points and repeating some of the warnings :

- there is no 'quick and easy' method of obtaining information on users' needs or their information-seeking behaviour; nor is there any single combination of investigative methods that will suffice for all situations;

- time spent in planning an investigation within the context of a total programme of user training and with specific training objectives in mind will be time well spent.

As to the warnings:

- DO define the user group of interest carefully, so that there is a strong probability that its training needs will be homogeneous. The corollary to this is that if the study reveals sub-groups with specific needs they need to be catered to specifically.

- DO distinguish between information NEEDS and INFORMATION SEEKING and decide which of these areas is of real significance for the overall programme.

- DO identify the specific training issues upon which you needguidance and design your study accordingly.

- DON'T choose investigative methods that are inappropriate to the kind of data you need. It may be much more appropriate and possibly cheaper to sit down and analyse documents than to carry out a field investigation.

- DO define the categories of data you need to collect and choose measures for those categories that are a) relevant and b) feasible.

- DO seek expert guidance on the conduct of an investigation and on the analysis of the resulting data.

- DON'T conduct a user needs study in ignorance of the resources that are available, accessible and already used.