Information Research

Vol. 28 No. 3 2023

The informational “cosplay journey” of Star Wars cosplayers in the context of a Facebook group

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir283199

Abstract

Introduction. Research on personal information practices has increased in recent decades. Building on this current of thought, the present study explores information practices in the context of serious leisure, looking specifically at the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group, an online community of Star Wars cosplayers. The work discusses how these fans seek, organize, and share relevant information during the process of making costumes.

Method. This study used participant observation and semi-structured interviews to investigate information behaviour, including information seeking, organization, use, and sharing, of seventeen members in the Rey Cosplay Community with a purposive sampling strategy.

Analysis. The researchers transcribed and jointly coded the collected data with an open coding scheme to identify themes that emerged from the data.

Results. The cosplayers used a myriad of tools to seek, organize, and share information about costume making. Participants identified that their information practices had evolved over time, and they shared sophisticated strategies for sharing work-in-progress photos and updates as well as methods for organizing information for later use.

Conclusion. There are a variety of information practices used when making a costume. Participants often seek and acquire relevant information on online platforms and use a combination of traditional physical tools and modern electronic tools to organize information. They also display a rich culture of sharing information when responding to other fans’ information needs. The overall structure that these ninformation practices take can be neatly articulated as a sort of informational “cosplay journey.”

Introduction

Cosplay (a portmanteau of the words costume and play) is ‘people dressing up and performing as characters from popular media, including comics, animated or live action films, television, games, and other pop culture sources such as music videos’ (Mountfort et al. 2019, p. 3). An almost ubiquitous part of the fandom experience (Lamerichs, 2018), cosplay has engendered robust networks of fans, both on- and offline, dedicated to the dissemination of cosplay-related information. One such network is the Rey Cosplay Community, a Facebook-based group that was established for individuals interested in cosplaying as the character Rey, the main protagonist from the most recent Star Wars film trilogy. Through this Web portal, participants interact with one another by expressing ideas, requesting feedback, sharing images, offering suggestions, and encouraging other members. Positive community norms, consensus on toxic fan behaviour, strong emotional bonds among members, and strict management of negative behaviour within the community by administrators promote the growth of the community and the members (Vardell et al., 2021).

Researchers have previously explored “fan studies” (e.g., Bacon-Smith, 1992; Jenkins, 1992; Hills, 2002; Booth, 2015), concepts of information practices (e.g., Caidi et al., 2010; Fry, 2006; McKenzie, 2002), and personal information management (e.g., Boardman and Sassee, 2004; Landsdale, 1988; Whittaker et al., 2016) separately, but few studies have covered all three domains by considering the information practices of cosplayers. This is something of a scholarly oversight, given that cosplayers utilize a bevy of information practices and personal information management methods to enrich their lives. This qualitative study sought to apply an information science researcher lens to the world of cosplayers to discover and describe the information-rich cosplay journey that members of the Rey Cosplay Community take when constructing costumes.

Some may ask what the importance is of a study looking at Star Wars cosplay fans. It is a fair question, and at first glance, such behavior may seem inconsequential in the grand scheme of information science. But as this descriptive article will demonstrate, cosplayers are navigating and employing social media in many innovative ways, either to communicate, crowd-source information, or problem solve informational hurdles; what is more, the overall process by which they grow from cosplay novices to cosplay masters can be neatly articulated as a sort of informational cosplay journey. This journey, upon which much of this article focuses, is thus an exemplar of a complex knot of information behaviour that has emerged organically online yet has so far escaped wider consideration in either fandom studies or information science. This study thus adds to the literature by further exploring the ways social media impacts and helps shape human information practices in our highly connected, digital world.

Literature Review

This study is firmly grounded in the field of information practices, which focuses on both the actions of an individual and the product of the actions as linked and dependent (Ávila Araújo, 2019). The discipline of information practice builds on the study of everyday life information seeking and personal information behaviour, and therefore, is well positioned as a framework for exploring individuals who undertake serious leisure activities.

Information practices and personal information management

Savolainen (2007) argues that the root of information practice studies can be traced back to Gidden (1984) and Suchman (1987), who approached the issue from a sociological and anthropological perspective, respectively. The two argued that individuals are knowledgeable entities who monitor and navigate their unique socio-cultural contexts. In an analysis of scholarly information practices, Savolainen (2007), citing Talja and Maula (2003), argued that special attention ought to be given to ‘the ways in which these practices are embedded within the overarching context of disciplinary differences in order to develop a holistic understanding of scholarly communities’ work and communication practices’ (p. 120). Additionally, several scholars, such as Dervin (1999) and Savolainen (2007), have argued that non-individualist information seeking, using, and sharing in a specific context should also be regarded as information practices. This understanding of information practices focused on work done collaboratively by organizing interactions and using supporting technologies (e.g., ‘information objects and information repositories’, Savolainen, 2007, p. 123).

A related topic is that of personal information management, which includes all activities related to obtaining and collecting new online personal information (e.g., intentional searches and unintentional encounters), organizing acquired information into a personal collection (e.g., creating folders on computers or phones), and re-accessing information for reuse (Bruce et al., 2011; Lansdale, 1988). The term personal information management was popularized by Lansdale (1988) at a time when researchers were enthusiastic about personal computers’ potential for information management (Jones, 2008b), leading many scholars to research users managing information electronically via tools like personal computer files (Barreau and Nardi, 1995), webpages, and e-mails (Jones et al., 2014).

Bates (2002) proposed the concept of an individualized information world for users, wherein users find information by creating subsets of information sources according to the use of information (e.g., work, entertainment, and daily decisions). Boardman and Sasse (2004) also reported that individuals usually created files for various projects and named the files after the projects’ names. When projects had relatively longer duration time or more complex internal structures, individuals tended to create subsets of files for the projects. Bruce et al. (2011) later argued that individuals’ approach to information management evolves from the planning phase to completion of the project.

Facilitating re-accessing information is one of the critical purposes of personal information management activities (Bruce et al., 2004a; Bruce et al., 2004b; Jones, 2008a). Steps to manage information re-access, according to Bruce et al. (2004b), include determining whether the information is relevant or useful, then ‘collecting, representing, indexing, cataloguing, classifying, and storing the information’ (Keeping (leaving) and re-finding information, para. 2). If an individual finds useful information on a site they frequently use, they will often eschew saving it to a .doc or .pdf file, since they can always visit the site and easily re-access the information in question (Bruce et al., 2004b).

However, the information organization tools' diversity creates additional problems, such as information fragmentation, as these tools can lead to inconsistent information management strategies (Bergman et al., 2006; Jones, 2008a; Jones and Maier, 2003). Further, Jones et al. (2005) argue that the diversity of available tools may also cause scattered storage on various devices, providing the example of an individual’s personal information spread across their office computer, home computer, and mobile devices. These problems, caused by the lack of integration between new and information management strategies, create barriers to re-accessing stored information (Jones et al., 2005).

Information practices and personal information management for serious leisure

Stebbins (2009) defines serious leisure as,

‘the systematic pursuit of an amateur, hobbyist, or volunteer core activity that people find so substantial, interesting, and fulfilling that, in the typical case, they launch themselves on a (leisure) career centered [sic] on acquiring and expressing a combination of its special skills, knowledge, and experience’ (p. 622).

Accordingly, Lee and Trace (2009) argue that serious leisure activities usually require a certain degree of dedication coupled with a specific knowledge base. The study of information behaviour vis-à-vis leisure emerged largely in the 1990s (Lee and Trace, 2009); notable studies have looked at information encounters during recreational reading (Ross, 1999), information action of those interested in the supernatural (Kari, 1999), the information behaviour of hobbyist cooks (Hartel, 2006), and information behaviour in knitting groups (Prigoda and McKenzie, 2007).

From the perspective of information behaviour studies, Pollak (2015), inspired by the concepts put forth by Savolainen (1995) and Stebbins (2009), considered the serious leisure of rural Canadians. Many leisure activities were practice-based, such as fishing and hunting, which required experience in order to excel. Novices therefore relied on the process of ‘interpersonal information sharing’ (p. 193); that is, learning from others with more experience. Pollak (2015) also noted that ‘informal information channels and interpersonal sources are frequently preferred over formal ones, and that contextual factors continue to influence information seeking and use across the domains of work, play and everyday life’ (p. iii). By studying information seeking, a behaviour defined by Allen (1996) as ‘the directly observable evidence of information needs and the only basis upon which to judge both the nature of the need and its satisfaction’ (p. 56), information science researchers can come to better understand the many information needs common to serious leisure participants.

From the perspective of personal information management, Cox and Blake (2011) investigated the information management strategies of serious leisure hobbyists who use blogs to seek and share gourmet cooking information. They noted that the hobbyists typically stored acquired information in Excel, clippings, notebooks, personal computers, and web favourites. However, the saving and retrieving of information was not what the hobbyists actively paid much attention to, for ‘the blog itself acted as a form of information organisation, through which text and carefully selected and edited images were organised in an easy to retrieve way’ (p. 216). Similarly, Lee et al. (2021) discussed the approaches that crafting enthusiasts used to organize information on Pinterest to learn skills for creative projects. Bullard (2016) explored the user-driven classification system of fan volunteers for online fan fiction collections with a library science perspective.

Our current study adds to the body of serious leisure research by exploring the information practices of cosplayers, thereby building on the small number of publications (e.g., Hill and Pecoskie, 2017; Hirsch, 2021; Vardell et al., 2020; Vardell et al., 2022) that have explored fan studies through the lens of information behaviour. Price (2017) investigated the information behaviour of fan groups on the Internet in her doctoral dissertation, where she found that the organization of fans’ works was usually based on the community-generated ontology. Study participants searched for information according to folksonomies of the community (such as uniform keywords or tags) when they retrieved information on the community websites.

When it comes to fan-made cosplay costumes, the serious leisure activities require skills involving costume design, construction, makeup, and prop making (Rosenberg and Letamendi, 2013). This, too, was noted by Hirsch (2021), who documented a variety of creative information literacy practices employed by cosplayers. In a study on fans’ use of an online community to obtain information about making costumes, Vardell et al. (2020) and Vardell et al. (2022) found that well-organized online communities could provide significant assistance for making costumes. However, there has been little research on the information practices of cosplayers and how fans manage and organize information obtained from online communities.

Methods

Participants

For this study, the researchers interviewed seventeen members of the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group, an online community for individuals interested in cosplaying (or creating and wearing costumes for) the character Rey, the main protagonist from the most recent Star Wars film trilogy. This project made use of purposive sampling methods, which reports like that by Campbell et al. (2016) have shown is an effective method when studying fan behaviour. First, the researchers observed the Facebook group, identifying active individuals (i.e., individuals who often contributed to the group by commenting on posts, liking people’s content, etc.) who had recently finished creating a costume. One member of the researcher team, who has long been a member of the Rey Cosplay Community, was tasked with reaching out to possible recruits through Facebook Messenger. All of the participants were explicitly given the option to decline the interview request, an option which several chose.

Our final sample included two individuals who were both administrators of the Rey Cosplay Community, as well as judges of the Rebel Legion (an international and well-established Star Wars costuming organization of individuals who create and wear screen accurate reproductions of costumes); the remainder of the group were composed of general members of the Rey Cosplay Community. In terms of nationality, fourteen of the seventeen participants were from the U.S, two from the U.K., and one was from Germany. Our sample also reflected a range of cosplay experience: Six of our participants had been actively cosplaying for between one and three years, five had four to nine years of experience, and seven had been cosplaying for ten years or more. The participants had a variety of occupations, including teacher, librarian, interior decorator, and salesperson in a fabric store. In addition to participating in the Rey Cosplay Community, several participants are also active members of other cosplay communities both on and offline.

Materials

Researchers sent informed consent forms containing the study's research purpose, procedures, confidentiality, benefits and risks, and researchers’ contact information to participants before the semi-structured interviews. The semi-structured interviews were conducted through Zoom in May and June of 2020. The interview questions were designed based on relevant literature on personal information practices and management (including information needs, seeking, organizing, and sharing). The interview questions were pilot tested with cosplayers from another online cosplay community.

Design and Procedure

This project employed a non-experimental, qualitative research approach that aimed to determine the information needs of cosplayers during costume making and the behaviour and tools used for seeking, organizing, and sharing costume-making information. At the beginning of the semi-structured interviews, the researchers explained the confidentiality of data collection and the potential use of the findings to participants. The researchers started with a list of prescribed questions from a semi-structured interview guide, followed by probes and follow-up questions to investigate participating cosplayers’ experiences. The interviews were conducted in May and June of 2020 via the video conferencing platform Zoom. No incentives were distributed. The interviews lasted between a half-hour and an hour. At the end of the interviews, researchers asked if participants would share information organization-related images that illustrate what was discussed in the interview. Noteworthy examples are included with permission in this publication to demonstrate the variety of approaches.

The researchers transcribed the qualitative data collected during interviews, analysed the first four participants’ transcripts with an open coding scheme, looked for emerging patterns/codes from the transcripts, and compiled a codebook. The rest of the transcripts were encoded according to the codebook. The three researchers coded all the transcripts separately and then discussed the codes during meetings. The researchers discussed any disagreements until a consensus was reached. If new patterns began to appear during analysis of subsequent interview transcripts, a new code was added to the codebook; the previously encoded transcripts were re-coded to incorporate new codes.

To supplement information derived from qualitative interviews, the researchers also employed participant observation (Kawulich, 2005; Spradley, 2016) to better study the Facebook-based group. This participation meant that the study's three researchers joined the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook page as active members (with the express permission of the page’s admins, who were informed as to the nature of our work), and they observe how cosplayers shared, searched for, and organized information. The researchers also made comments or interacted with group posts when appropriate; this allowed the researchers to gain a more “emic” (i.e., “insider”) understanding of the community (Geertz, 1983), thereby enriching the study’s conclusions.

The participant observation phase of this project entailed three processes of varying analytic depth (Spradley, 2016; Werner and Schoepfle, 1987). The researchers first made general descriptive observations about the information behaviour they noticed. The information collected was, at first, abundant and loosely organized. Information from interviews was then combined with this loose body of descriptive knowledge; this allowed for more focused observation of the group’s behaviour, with the information provided by the interviewees acting like arrow, pointing the researchers towards behaviour that was truly striking (Kawulich, 2005). During this portion of the participant observation phase, attention was paid to unique key words and phrases used by the participants (Merriam, 1998). This all led to the final process: that of selective observation, whereby the researchers began to identify and describe generalized patterns of behaviour (Kawulich, 2005). This, in turn, enabled componential analysis and subcultural thematic analysis (Spradley, 2016), resulting in the articulation of a cosplay journey.

Findings: a cosplay journey

The overarching idea of a cosplay journey used to frame this study was taken from a direct participant quote:

This hasn’t just been my Rey cosplay journey. It’s been my sewing journey. This is how I learned to sew (P3).

Upon meditating on this quote, we noted that participants tended to frame their experiences in a similar way, outlining their own journey, from idea to rough concept to first draft to final costume. Along the way, they grew in skill, growing from beginners to master.

Information need

Many frequently cited information models and research studies identify information needs as the precursor to the initiation of information behaviour, such as seeking, sharing, and using. This was also the case with the cosplayers interviewed in this study, all of whom cited some sort of information need as an initiating factor for their cosplay journey. Identifying the correct fabric colour and texture was perhaps the most common issue that our participants ran into, with Participant 2 explaining:

‘A lot of the girls have had [the] same trouble when trying to find the correct colour for the costume’.

Unfortunately, while, as Participant 1 notes,

‘every cosplayer’s dream is [to ask the production staff]: “Oh, so where did you shop for that fabric?”’

disclosure agreements and other limitations often restrict official sources from sharing such specific details. These legal roadblocks thus lead to a dearth of official information about the costumes in question, necessitating that the cosplayers track down appropriate information themselves. And in addition to the many questions about the materiality of the costumes, other individuals with whom we spoke expressed their interest in guides that might detail how exactly one creates a costume. This was voiced most cogently by Participant 10, who told us:

‘I always wish that there was like a comprehensive set of instructions on how to make everything.’

(Cosplayer-created tutorials and other resources will be discussed further in the next section.)

Information seeking

The types of information sought by most participants were reference images (e.g., images of exhibition costumes, film stills, work-in-progress photos, and behind-the-scenes photos) and costume-making tutorials (e.g., sewing and dyeing fabric). Several participants described looking for very detailed information, such as the types of fabrics and other materials (e.g., leather) used in a costume, as well as places to purchase, the availability of past tutorials, and experiences of other group members. Online platforms such as cosplay-related websites and social media, including the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group, online forums, YouTube, blogs, Pinterest, and Instagram, provided participants with a large amount of information about costume making. Offline resources, such as friends, family members, craft shops (e.g., Jo-Ann stores), film premieres, and libraries complemented online resources to provide participants with the information they needed. These sources and channels (i.e., ‘the medium used to convey information’ (Case and Givens, 2016, p. 368)) will be explored further in the following sections.

Information monitoring

Another behaviour that many of this study’s participants mentioned was that of information monitoring. In this case, monitoring refers to the ‘tendency of a person to actively scan the environment for information relevant to their concerns’ (Case and Givens, 2016, p. 373). This sort of monitoring differs from information seeking proper in that it is often incidental and something of a passive endeavour. Perhaps Participant 6 expressed this most clearly when she explained:

‘I’m not actively looking for information [to improve my costume], but if it's something I could [use] or if it’s not too hard, I'm always looking at improving it.’

In this instance, our participant noted that while she was not longer looking for specific information, she nevertheless remained cognizant of the group’s postings because there could be a post that might prove useful in the future. Information monitoring can be something of a tricky balancing act, as it can very easily lead a participant into a seemingly endless cycle of self-criticism; Participant 3 warned of this when she told us:

‘I will keep active in the group and keep my eye out for changes and maybe better resources … but for the most part, once I've kind of mentally completed a project, I try to put it down because I will pick it to death.’

Information sources and channels

Expert Advice.

Almost all our informants told us that when it came time to solicit information about their costume, they first turned to those close to them—such as friends or family members—for expert advice and were a primary information source (i.e., the ‘individual or institution that originates the information’; Rogers, 2003). Parents are often a go-to source, with many, included Participant 10, citing their mothers as experts:

‘My first port of call is usually [her] mom, to see how she would do things or what she thinks of different styles.’

But despite the importance of mothers, other family members could be equally as important—Participant 4 notably told us:

‘When I was figuring out how to print the helmet, my cousin works for an aerospace industry company that has a 3D printer... He was giving me pointers about how to slice up.’

Other people to whom our informants reached out included close personal friends, as well as acquaintances that they had made online; it was common for these friends to be Star Wars fans and/or members of the cosplay community, as this provided them with the knowledge base to discuss the project.

After exhausting the expertise of friends and family members, participants then usually turned to the internet. For many of the cosplayers with whom we spoke, it is at this point that the Rey Cosplay Community entered the equation. Some of our participants explained that they found the group by themselves, whereas others, like Participant 10, told us that they were directed toward the group by other, more ‘in the know’ cosplayers:

‘I was on a mad Google session for the new [Rey] costume, and [someone] mentioned the Rey community. So I just put that in, and I found the page and thought, “If anyone can help me out with the new costume, it’s probably them”.’

As evinced by the last part of Participant 10’s statement, many of the study’s participants recognized that the Rey Cosplay Community, as a group made specifically for Rey cosplayers, was likely to provide an excellent venue to solicit the expert opinions of others, more seasoned cosplayers. Individuals often did this by posting a question to the group’s timeline, commenting on other members’ posts with their queries, or by messaging members who seemed particularly knowledgeable about a given topic.

On the Rey Cosplay Community, expertise is intricately connected to reputation and social position of those in the online group. For instance, Participant 9 told us,

‘I and other people in the group trust [the name of one of the group's admins], who has made lots of commissions for people. I trust [her insight].’

In this instance, the reputation of this admin was well-known because of her past actions, her expert advice, and her position as a group leader. Because of these factors, Participant 9 and her associates consequently had no problem turning to this individual whenever they had informational questions about which they thought she could help. Several of our other informants named the group’s admins as key information sources, too. Participant 15, for example, told us that she

‘look[s] to [the group’s admins] as leaders, because they're always giving advice on how to create costumes.’

this echoes what Participant 1 when she argued that because they had ‘been doing it [i.e., cosplaying] for so long’, the group’s admins had become the ‘sort of become go-to people for certain costumes’. These comments suggest that a member’s expertise (either real or perceived) often correlates with group leadership; the greater the member’s expertise, the more likely they are to be seen and serve as leaders.

Another closely related is that of constructive criticism, and indeed, many of our informants used the Rey Cosplay Community largely as a venue to solicit this sort of criticism while they worked on their costume. Consider, for instance, what Participant 15 noted:

‘As I'm working on projects or costumes or accessories, I like to post to get feedback on what I'm doing, whether it's good or bad or advice for improvements.’

With that said, many of our participants stressed that a key norm of the group was that participants are expected to give criticism only when a poster requests feedback. Participant 13 put it most succinctly when she told us,

‘The [main] unspoken rule is don’t give advice that people aren't asking for.’

Participant 3 expanded on the rationale for this norm:

‘We don't give any sort of criticism to anybody, unless they ask for it because the group is supposed to be a nice, and it's supposed to be welcoming place.’

Arguably, the sentiment expressed in these statements is one predicated on the idea that the Rey Cosplay Community is supposed to be founded on an ethos of positivity. This assumption fundamentally precludes unsolicited feedback, given that some people in the group simply want to share what they are working on with others, rather than have their creations nit-picked or critiqued. It is likely that this norm developed as a reaction to toxic gatekeeping behaviour that our participants implied were prevalent in other cosplay spaces.

Work-in-progress photos.

Another unusual aspect of cosplayer information practices is the documenting and sharing of work-in-progress photos. Cosplayers have a variety of reasons for documenting their progress through work-in-progress photos. Some may take work-in-progress photos as a pre-emptive measure assuming other cosplayers may turn to them for assistance in the future:

‘One of the big ways that I document is trying to take pictures at every step of the way. I don't remember what I did when I did it. I know people are going to ask. I try to take a picture of each step.’ (P4).

Participant 10 explained a fairly popular strategy of using Instagram story highlights to share work-in-progress photos of a specific project for the purposes of assisting fellow cosplayers:

‘I’ve started using highlights, because I find if I’m in the middle of making something, I don't want to stop and pause, make an Instagram post or take a picture, and write a whole thing about what I was doing. But if I do an Instagram story and a quick caption on that and then later I can add it to highlight, anyone looking at my Instagram page can cycle through and see how I did things.’

Still others may have learned from the past that they may want these photos to refer back to themselves when constructing similar items:

‘It needs to match my current staff because I can take it apart into three pieces, but I was wondering if I used this spray paint. I don't remember. I went back into my photos, and I found a picture of my work-in-progress stuff. I was like, “yeah, … there's the paint I used”’ (P5).

Work-in-progress photos are also an integral part of obtaining guidance. Participant 6 described a time when she used work-in-progress photos to obtain advice from others who had experience with similar issues:

‘I tried to take a picture of it, say this is what it looks like. That's not what it's supposed to look like. Here's the reference of the original. I'm trying to get that seam to move to the right. It's not standing up the right way and I asked can anyone help me or tell me what's the problem.’

In fact, cosplayers may use others’ work-in-progress photos that they have shared in social media as a part of their information files for a particular build:

‘like work-in-progress photos -- people have put those up and ... then I always make a photo album in my Google Photos of all my reference photos, which is a little awkward because sometimes they have other people, from their public photos from Facebook and stuff.’ (P7)

For some cosplayers, work-in-progress photos serve more emotional purposes. For example, Participant 7 reflected that,

‘part of it is accountability, like if you're posting work-in-progress, people are like, how's that going.’

Sharing work-in-progress photos is yet another way for people to build community, provide support, and help encourage others to meet their goals. For many taking and sharing work-in-progress photos is a way to reflect on their own progress with individual costumes or during their cosplay journeys:

‘Part of this for me to have work-in-progress [photos] … [is to] see how far I've come’ (P5).

Facebook albums.

Because the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group is so heavily trafficked by those looking for information, group members have dedicated time and effort to creating a wealth of information resources embedded within the Facebook group. These information sources assist cosplayers in building each of the costumes, props, and other items associated with the character Rey:

‘it's actually the most detailed file folder of any group I've ever seen on Facebook. There are different subsections for each costume’. (P9).

The Rey Cosplay Community includes Facebook files and image albums curated to identify the steps and materials needed to create each of the costumes worn by the character Rey. These sophisticated information sources make it possible for cosplayers to seek and use the most helpful information in one place:

‘It’s the connections that I'm able to make in the Rey Cosplay Community on Facebook [that] made it possible for me to do these costumes. I wouldn't have been able to do them as accurately, maybe not at all, if it weren't for the support from that group”. (P9)

One of the more unique information resources within the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group are the step-by-step tutorials that members have created to walk fellow cosplayers through each of the tasks needed to create a specific piece of the costume (e.g., modify pants with the screen accurate seams or a pair of boots with the correct detailing). These tutorials are located in the community’s Media section (see Figure 1), and they make use of Facebook’s photo album capabilities. As such, they are primarily visual in nature, although they often include text or videos for further clarification. This mix of visual and textual instruction was important, as it accommodated a variety of learning styles; as Participant 3 put it:

‘That really helps because I'm a visual learner. I can read how you did it all day long, and I won't get it. But if you post step-by-step photos of how you assembled something, it'll make sense.

Figure 1. A random selection of Facebook albums on the Rey Cosplay Community page. Many of these albums (such as the one labelled “Resistance Rey Build”) function as step-by-step costume tutorials

An excellent example of one such tutorial is the Resistance Rey Build album of 89 photos, which walks users through the process of constructing a specific type of garment (the eponymous Resistance Vest) worn by Rey. The album opens with four images of a mock-up vest the participant created to determine the final costume’s exact fit; these images have been annotated by the album creator, indicating areas of the mock-up with which she was unhappy. The next few images after the mock-ups illustrate the individual pieces of fabric that will comprise the vest, laid out and organized by layer and fabric type. From here, the album shifts its focus and delineates the actual process by which the vest is constructed. The creator of the album first illustrates how and where the pieces should be pinned before demonstrating which pieces need to sewed together. The creator also illustrates which pieces need to be trimmed, steam pressed, or clamped together. The final dozen or so images exhibit the finished vest from various directions so that users will have a solid visual understand of what the vest is supposed to look like when all is said and done.

Using the Facebook album structure for these tutorials indexes a sort of human creativity, leveraging an already-existing digital structure (i.e., a Facebook photo album) and turning it into something new (i.e., a tutorial). But this strategy is also a pragmatic one, given that it provides Rey Cosplay Community members with a convenient, centralized place to discuss and expand upon particular costumes of interest. The Resistance Rey Build album, for instance, has engendered several comment chains, of which one is a question about fabric use. The creator of the album also used this comment space to post a supplementary video about her blanket-stitching technique, thereby expanding upon her initial tutorial. Several of the informants, including Participant 3, also pointed out that Facebook’s built-in features also allow participants to quickly share tutorials with others, as well as pin it and save a given tutorial to their own profile for later access.

But what is it that motivates individuals to create tutorials? According to Participant 6:

‘I've gained so much from asking other people and from the tutorials and patterns they have shared. That is giving and taking. I got information from you, if I have good useful tips and tricks, I'm trying to give something back and inspire others to share so that we all may have a profit from this informational game… Keep a cycle of sharing information.’

Information organization

Cosplayers use a variety of information organization strategies to manage the all-important resource of costume images (including screenshots from films, images of costumes completed by others, and patterns), video and image tutorials, and detailed material information for making the costumes. The prime goal of organizing the information was to be able to find and use the information conveniently while building their costumes or with the goal of creating tutorials to provide assistance to others in the future. Cosplay notebooks, cell phones, and computers were frequently mentioned media used for participants’ information organization. Some of them used only one of the four media, while others used the four in complementary approaches when one medium could not meet all of their needs for information organization. Participant 1 described how she used a combination of strategies:

‘I start first and foremost by finding photos of the costume and most of the time I start making a folder, either on my phone or on my computer … I would print out photos of the costumes … then I take them home and I would compile a notebook of the pictures and I write things down or sketch out the costume if needed.’

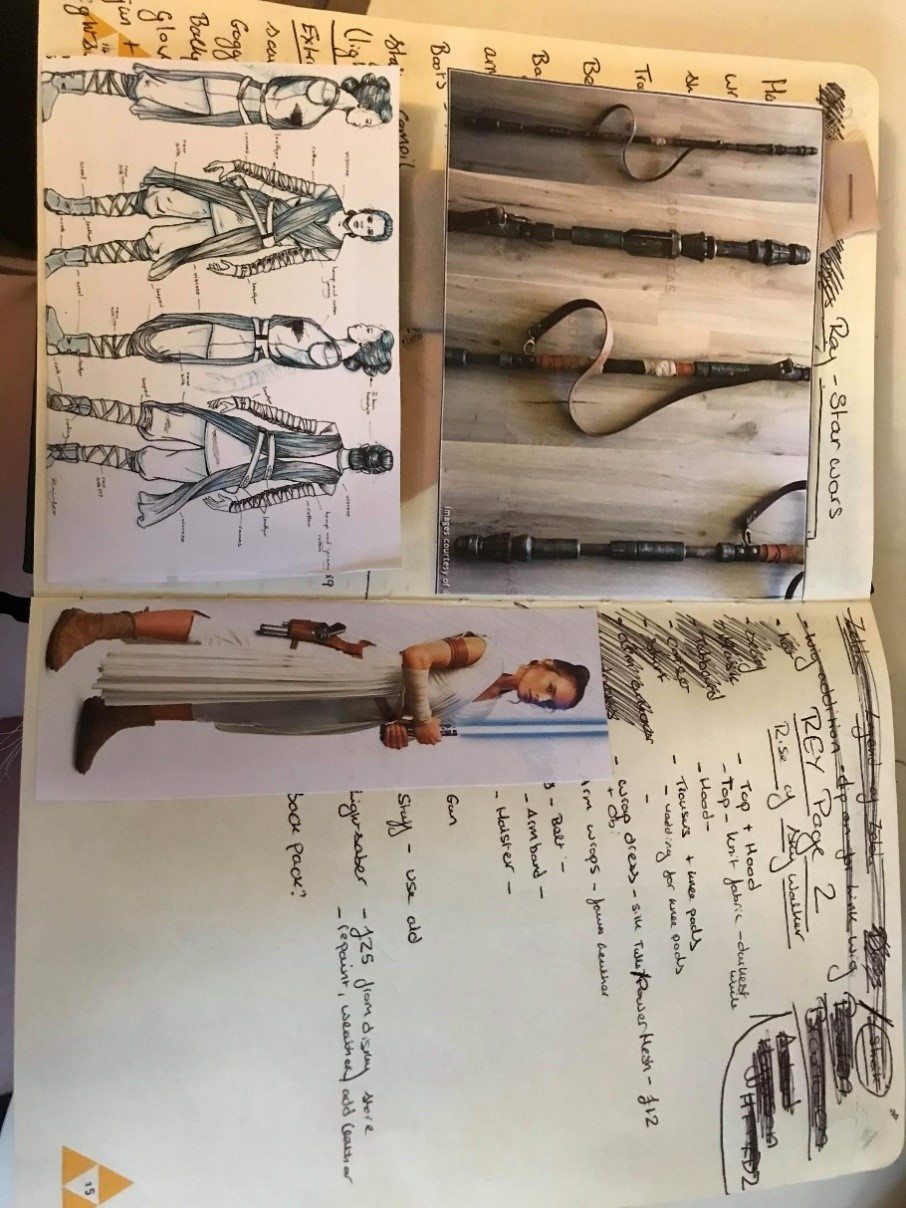

Notebooks.

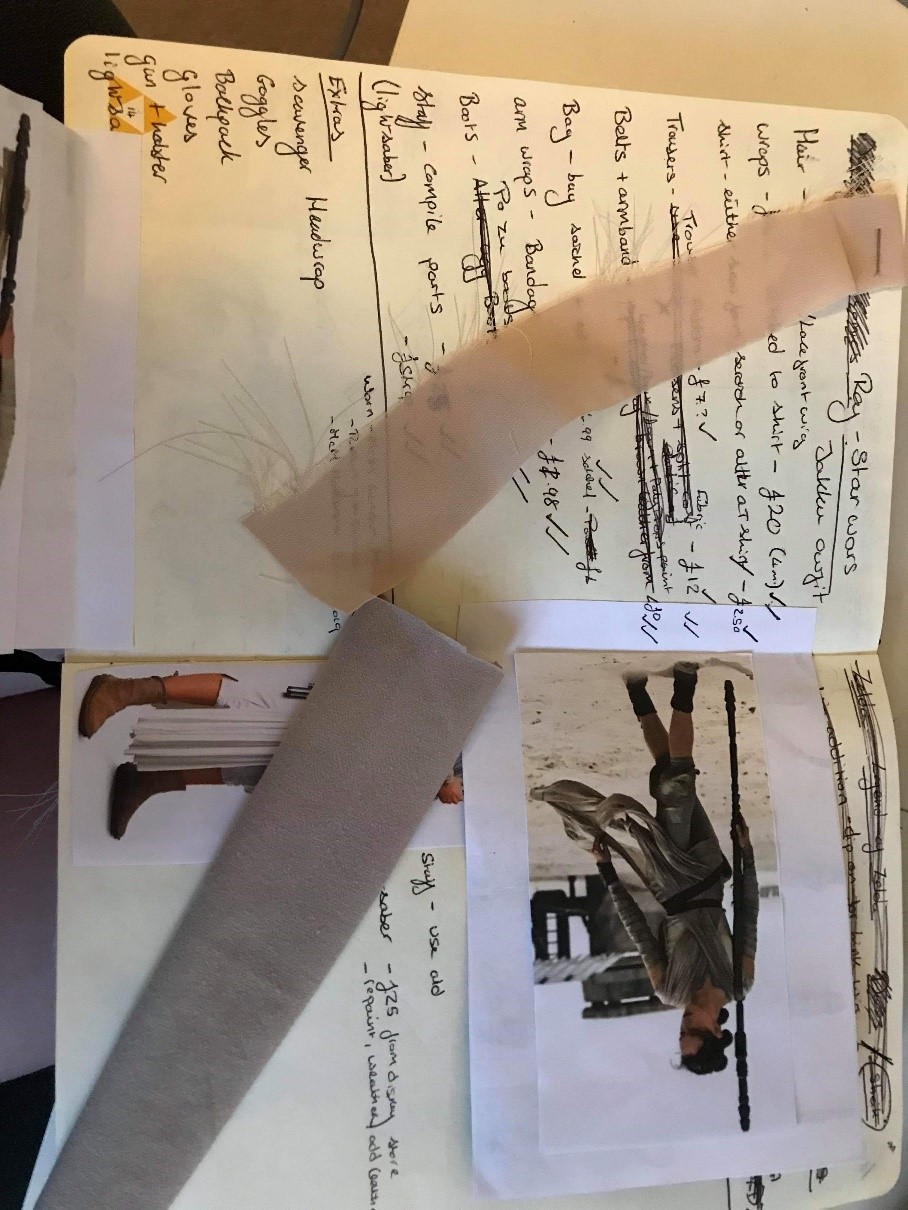

Many participants described using a notebook to organize information, writing down each piece of clothing and organizing them into sections or pieces of a costume, such as belts or Jedi tabards. Figure 2 demonstrates one example of how participants would use notebooks in a variety of creative ways, including listing out necessary items, pasting in reference photos from film stills, and even including fabric scraps to test out ideas.

Figure 2. List of materials, budget estimates, reference images, and fabric scraps for a target costume

Computers.

Those who organized information on a computer took a similar approach: for example, one participant described how she created a main folder on her desktop for Rey costumes and then set up sub-folders according to each Rey costume. Within the sub-folders, information about various parts of costumes was saved. Figure 3 shows Participant 5’s approach to information organization on her computer. Participants used checklists to list the necessary steps in completing costumes. Such an information organization approach was also observed in the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group, making it easy for team members to search for information within the group. As Participant 9 expressed,

‘with the Rey community, even if I forgot something, I could easily track it down again, like a piece of information or a link or some recommendation.’

Figure 3. Organizing information with a computer

Cell phones.

Cell phones played an essential role during the information seeking, organizing, and costume planning process. Cell phones were used for saving posts from social media and making costume work plans. Compared with the computer and traditional notebook, cell phones were more portable and convenient for collecting and saving information from the Internet (usually by screenshots) and recording minor things about making costumes. Some participants started with seeking and recording information on cell phones, then transferred the most helpful information to a computer or a notebook for further use. Other participants described recording information from the Internet on a computer then uploading to cloud storage, such as Google Photos, so that they could access to the information by cell phone anytime and anywhere.

Saving posts.

Cosplayers use the Save Post function in Facebook and Instagram as a point-of-need strategy for saving helpful information for later use. One of the most significant reasons for saving posts was to provide a convenient method of later use of the information without returning to the Facebook group or other forums and information sharing platforms. The posts were usually organized and saved on notebooks, computers, cell phones, and other tools according to personal preferences. The most common electronic platforms used by participants for seeking, saving, and organizing collected information were Pinterest, Instagram, and Facebook.

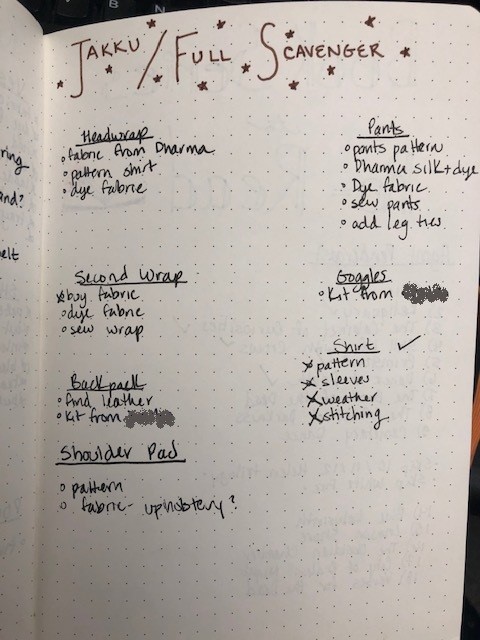

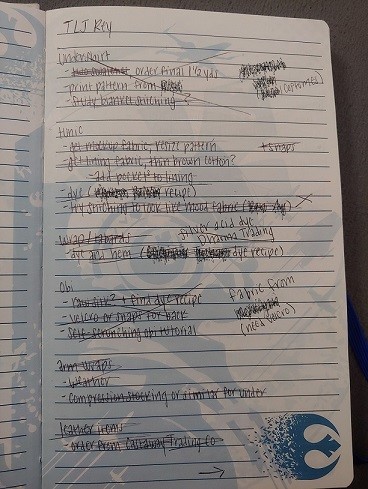

Making lists.

Lists made with manual or electronic notebooks or cell phone apps were used for recording the materials, parts, and plans for a desired costume. Figures 4 and 5 exhibit lists made manually in Participants 10 and 16’s notebooks. Figure 4 shows how a notebook might include a list of necessary elements, photos from official sources (on the right-hand page), as well as photos shared within the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group (on the left-hand page).

Figure 4. List of parts for a costume

Several participants stated that a list was also a method for distinguishing between what they would work on by themselves and what would be commission to be made by others (e.g., in Figure 5 the item, kit from Kristen, indicates the cosplayer plans to buy a pair of goggles and a backpack kit from another Facebook group member).

Figure 5. List of process plans for the Jakku/Full Scavenger costume.

In addition to making it easier to purchase materials, create costumes, and share experiences with other members of the Facebook group, cosplayers also look forward to obtaining a sense of accomplishment when crossing off the completed sections. When asked about her approach to tackling a costume, Participant 5 narrated

‘Let me make a list. Let me start checking off those little boxes. Sometimes finding the motivation is just starting small and checking off those little boxes.’

Figure 6 shows evidence of Participant 9 crossing off the completed items in her notebook to do list.

Figure 6. Completed sections in a notebook to do list.

Evolution of information organization strategies.

As cosplayers costume building skills evolve over time, so do their approaches to organizing necessary information. Many participants in this study expressed that their information organization approaches had been generally the same during their cosplay journey but shared that over time their information organization systems have become more detailed. Others acknowledged that their information organization strategies evolved through use of different tools or platforms for organizing helpful information. Several participants who started out with not using any tools switched to using a physical or digital tool when they realized they had a significant amount of information to organize. Many participants toggled between traditional information organization tools, such as notebooks, and digital tools, such as computer software (e.g., Word and Excel) and cell phone apps (e.g., Cosplanner, Instagram, Pinterest, and SmugMug). The cell phone application Cosplanner (http://www.cosplanner.net/) was the most often mentioned information organization tool, which helps cosplayers list all the required materials for a costume to be completed and assists in making an itemized budget and timeline for users.

The reasons for changing information organization approaches included difficulties with a previous approach to organizing, as when Participant 11 said:

‘I did start out trying to do it on the computer, but I found that to be too much trouble to me. Writing it down by hand on my planner was just a lot easier.’

Another reason for an evolving approach to information organization was when cosplayers identified difficulty in access cosplay information that was mixed in with other information, as Participant 13 stated:

“I was scrolling through pictures of my dog and pictures of my vacation, like, hold on, I have a picture that I got to find. It got super annoying. I started to organize them by costume.’

Information sharing

When a group member reached a certain skill or confidence level, they often began sharing information with other cosplay neophytes. The main types of information shared in the Rey Cosplay Community at large included tutorials of making components of a costume, fabrics and other materials, patterns, images of works-in-progress and completed costumes, techniques, experiences, and videos for socializing (e.g., TikTok). Some participants also indicated that they exchanged ideas about a costume, such as a costume’s fabric, with a smaller circle of cosplayers before sharing the information in the Facebook group once a conclusion was reached.

There were diverse reasons for sharing information about making Rey costumes, such as the desire to contribute to the collective group information resources or to help or give back to others. It was the latter point that Participant 3 cited when she told us that she tries to ‘share what information and experiences’ she has had to make others cosplay journey somewhat easier; similarly, Participant 6 explained that she tries ‘to give forth [her] knowledge of what [she has] find out, what doesn't work and what works’. Other participants explained that their motivation to share information with the group was due to their professional careers (e.g., as teachers and librarians). Participant 1 expressed

‘I was a library assistant for many years. That was part of my job, researching [and] collecting information for people. It’s just part of what I enjoy doing.’

Conversely, our participants revealed that reluctance to share information was because no one asked them for information, or because they worried that their information was inaccurate.

In addition to the Rey Cosplay Community, our participants revealed that they shared information across a variety of platforms. Participants often mentioned social media sites like Instagram and Discord as avenues through which they would share digitized information, such as video tutorials, patterns, links, and images. Participant 11 also stated that she shared information at her job at a fabric store;

‘since I work at JoAnn’s, there are times when a customer will come in and ask for something, and I'll be like, oh, I know about that … even though I haven’t actually used it. There have been a lot of things that I've learned by reading and interacting [with other cosplayers] that I have been able to actually use at work, even if it hasn't been something I've done myself.’

Members of the Rey Cosplay Community are allowed to share information at any point, but many choose to do so only after they have a certain amount of experience. Consider, for instance, Participant 2, who told us that she

‘usually wait[s] to share stuff once [she] know[s] for sure that something’s going to work out.”

Likewise, Participant 3 mentioned that because she is ‘new at this’ and does not ‘really one hundred percent know what [she is] doing’, she will refrain from sharing information and “let the older girls take over.” These comments suggest that individuals only dabble in regular information sharing after they feel they have achieved a level of expertise with regard to some aspect of the costume-creating process. Regular information sharing can thus be understood as the final stage of an individual’s cosplay journey, given that at this point, the individual has largely transitioned from a neophyte who regularly seeks out information to a master who often provides informational expertise to others.

Discussion

This study explored Rey cosplayers' information practices in an online community and their personal information management strategies employed when making costumes. The research results indicate that family and friends with relevant skills (e.g., sewing and 3D printing) were the first preferred information sources for cosplayers. In her study, Pollak (2015) explained that, when it comes to leisure activities, interpersonal communication and informal information channels were more popular than official channels. Our current study expands upon Pollak's findings. The lack of information from authoritative sources (e.g., film costume designers) and the ease of obtaining information from the Rey Cosplay Community made this community an essential channel for cosplayers seeking information. In addition, as a community with a shared interest, it allows members to create and share knowledge or seek information around a common theme (Gee, 2017), which provides opportunities for cooperative learning exchanges (Shaffer et al., 2005) and to practice information literacy skills (Martin, 2012). Many of our participants spoke about how their searching improved through looking for cosplay materials without being prompted to self-reflect on this aspect. This self-awareness of improvement in information literacy skills through serious leisure is a potential area for further exploration.

Boardman and Sasse (2004) noted that individuals often named files according to the project names and created subset files as the project progresses. This finding was corroborated in the current study. When organizing and managing the collected information, participants classified information according to varied costumes and various parts of a costume. They saved information with digital tools (e.g., computers, cell phone files, and mobile applications) and/or traditional tools (e.g., cabinets and notebooks) in folders named after the costumes and costumes parts. As the costume-making progressed, the participants’ personal information management systems turned more detailed and sophisticated (Bruce et al., 2011). Given that the primary purpose of information management is to improve information re-accessibility (Jones and Maier, 2003), a detailed information management system is more likely to assist serious leisure enthusiasts in achieving this goal. It is worth noting that a similar approach to information management is used in the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group file and image information structures, facilitating information retrieval and collection by community members. Also, the information management method used by the community could inspire cosplayer novices on how to personally organize and manage collected information.

Lee et al. (2021) explained shopping list-making as a way of helping individuals remain efficient and save on shopping costs. During the crafting process, the use of the Pinterest board aided in inspiration, learning, and emotional stress-reducing (Lee et al., 2021). In the current study, members of the Rey Cosplay Community also described using lists for personal information management in costume making. Our findings are a confirmation and expansion of those of Lee et al. (2021) where members in a community worked towards shared goals of comprehensive lists and albums designed to assist with costume making within a group.

Jones et al. (2005) referred to information fragmentation due to multiple information management tools, which hindered re-accessing the collected information. In our current study, participants also described using various tools to manage costume-making information. However, we came to the opposite conclusion. Participants stated that they used different tools for information management because one, single instrument could not meet their needs. To make it easier to revisit the information, some participants combined information from various tools into a single tool, such as transferring categorized information from cell phones and computers into a physical notebook. For digital platforms (e.g., cell phones and computers), Oulasvirta and Sumari (2007) recommend potential solutions to information fragmentation caused by using multiple devices in mobile information work including ensuring data synchronization across devices. Physical objects used to manage information should be integrated as efficiently as possible for transportability and use. Therefore, cosplayers should ensure information collection and management tools' synchronization and portability to improve information accessibility.

Conclusion

In recent decades, fan studies research has increased significantly, and this study sought to apply an information sciences lens to this developing field. This study explored information practices in the context of serious leisure, looking specifically at the Rey Cosplay Community Facebook group, an online community of Star Wars cosplayers. This study focused on how these fans seek, organize, and share relevant information during the process of making costumes.

Limitations of this study include the timing of the semi-structured interviews (during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic), the almost exclusively female participants, and the scope of the study (a small portion of the broader fans virtual communities). These factors may lead to participants’ costume making or information behaviour not representing male and nonbinary or gender-queer cosplayers and the entire fan community. In future research, researchers may seek to interview other online cosplay communities’ members at different time points to verify the generality of the current findings. In addition, longitudinal research could also be an approach to explore the change and evolution of the information behaviour of online cosplay community members.

This descriptive study discussed cosplayers’ information practices and personal information management through semi-structured interviews and ethnographic methods. The results indicated that interpersonal information communication and an online community were critical information sources for cosplayers due to the lack of official, authoritative information. Cosplayers used a variety of tools and sophisticated strategies to seek, organize, manage, and share collected information. A variety of innovative information practices were employed by subjects in this process and participants often sought and acquired relevant information on online platforms using a combination of traditional physical tools and modern electronic tools to organize that information. These findings shed light on the current serious leisure practices of cosplayers, thereby providing rich descriptions of information practices that have long been overlooked but will likely be of much interest to researchers studying how individuals and, in particular, media fans, seek, organize, and share information.

Images were a core information source for cosplayers in this study. Works-in-progress photos, for example, were a way to document and share work as both an internal motivator and a way of paying-it-forward within the group where sharing strategies and tips was a way to enhance community bonds. Advice giving within the group was done with a fine balance—it was clear that advice should only be given as constructive criticism when directly asked for to maintain the supportive atmosphere in the group. In addition, expertise was discussed by participants who cited individuals with formal group responsibilities (i.e., admins) as correlating with expertise on creating costumes. The overall process under which these information practices flourish can be abstracted and nicely summarized as an informational cosplay journey, wherein participants (much like the Jedi knights whom they emulate) grow from apprentices into masters.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants for sharing their cosplay journeys. Thank you for inspiring people of all ages by cosplaying Rey.

About the authors

Emily Vardell is an associate professor in the School of Library and Information Management at Emporia State University. Her research interests focus broadly on information behaviour, including health insurance literacy, infertility information, and cosplay information practices. She also studies library science education best practices and trends. In her free time, she volunteers with the Rebel Legion as a Rey cosplayer. She can be contacted at evardell@emporia.edu.

Paul Thomas is a library specialist at the University of Kansas. He holds a PhD in Library and Information Management from Emporia State University, and his research interests include Wikipedia, popular culture, and fandom studies. He can be contacted at paulthomas@ku.edu.

Ting Wang is a recent graduate of the doctoral program in Library and Information Management at Emporia State University. Her research interests include health information behaviour and information behaviour in online communities. She can be contacted at twang2@g.emporia.edu.

References

Allen, B. L. (1996). Information tasks: Toward a user-centered approach to information systems. Academic Press.

Ávila Araújo, C. A. (2019). Information practices: the relevance of the concept to information user studies. Annals of Library & Information Studies, 66(3), 101–109. http://doi.org/10.56042/ALIS.V66I3.25764

Barreau, D., & Nardi, B. A. (1995). Finding and reminding: file organization from the desktop. SIGCHI Bulletin, 27(3), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1145/221296.221307

Bates, M. J. (2002). Toward an integrated model of information seeking and searching. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 3(1), 1–15. https://pages.gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/bates/articles/info_SeekSearch-i-030329.html (Internet Archive)

Bergman, O., Beyth-Marom, R., & Nachmias, R. (2006). The project fragmentation problem in personal information management. In R. Grinter, R. Rodden, P. Aoki, E. Cutrell, R. Jeffries, & G. M. Olson (Eds.), Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montréal Québec Canada, April 22-27, 2006 (pp. 271–274). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1124772.1124813

Boardman, R., & Sasse, M. A. (2004). Stuff goes into the computer and doesn’t come out: a cross-tool study of personal information management. In E. Dykstra-Erickson & M. Tscheligi (Eds.), CHI '04: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vienna, Austria, April 24-29, 2004 (pp. 584–590). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/985692.985766

Booth, P. (2015). Playing fans: Negotiating fandom and media in the digital age. University of Iowa Press.

Bruce, H., Jones, W., & Dumais, S. (2004a). Keeping and re‐finding information on the web: what do people do and what do they need? Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 41(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.1450410115

Bruce, H., Jones, W., & Dumais, S. (2004b). Information behavior that keeps found things found. Information Research, 10(1), paper 207. https://informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper207.html (Internet Archive)

Bruce, H., Wenning, A., Jones, E., Vinson, J., & Jones, W. (2011). Seeking an ideal solution to the management of personal information collections. Information Research, 16(1), paper 462. http://informationr.net/ir/16-1/paper462.html (Internet Archive)

Bullard, J. (2016). Motivating invisible contributions: framing volunteer classification design in a fanfiction repository. In S. Lukosch, A. Sarcevic, M. Lewkowicz, & M. Muller (Eds.), GROUP '16: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, Florida, United States, November 13-16, 2016 (pp. 181–193). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2957276.2957295

Campbell, J., Aragon, C., Davis, K., Evans, S., Evans, A., & Randall, D. (2016, February). Thousands of positive reviews: distributed mentoring in online fan communities. In D. Gergle & M. R. Morris (Eds.), CSCW '16: Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, San Francisco, CA, United States, February 27-March 2, 2016 (pp. 691–704). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2819934

Case, D. O. & Given, L. M. (2016). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (4th ed.). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Cox, A. M., & Blake, M. K. (2011). Information and food blogging as serious leisure. ASLIB Proceedings, 63(2/3), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012531111135664

Dervin, B. (1999). On studying information seeking methodologically: the implications of connecting metatheory to method. Information Processing and Management, 35(6), 727–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00023-0

Geertz, C. (1983). Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. Basic Books.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

Hartel, J. (2006). Information activities and resources in an episode of gourmet cooking. Information Research, 12(1), paper 282. http://informationr.net/ir/12-1/paper282.html (Internet Archive)

Hill, H., & Pecoskie, J. J. L. (2017). Information activities as serious leisure within the fanfiction community. Journal of Documentation, 73(5), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-04-2016-0045

Hills, M. (2002). Fan cultures. Routledge.

Hirsh, K. (2021). Where’d you get those Nightcrawler hands? The information literacy practices of cosplayers (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill PhD dissertation). https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/pc289s64m?locale=en

Jones, W. (2008a). Keeping found things found: The study and practice of personal information management. Morgan Kaufmann.

Jones, W. (2008b). Personal information management. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 41(1), 453–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2007.1440410117

Jones, W., Karger, D., Bergman, O., Franklin, M., Pratt, W., & Bates, M. (2005). Towards a unification & integration of PIM support. [Paper presentation]. The PIM Workshop, Seattle, WA, United States.

Jones, W., & Maier, D. (2003). Personal information management group report. [Paper presentation]. NSF IDM 2003 Workshop, Seattle, WA, United States.

Jones, W., Wenning, A., & Bruce, H. (2014). How do people re-find files, emails, and web pages? In M. Kindling & E. Greifeneder (Eds.), iConference 2014 Proceedings, Berlin, Germany, March 4-7, 2014 (pp. 552–564). iSchools. Kari, J. (1999). Paranormal information seeking in everyday life: the paranormal in information action. Information Research, 4(3). https://informationr.net/ir/4-2/isic/kari.html (Internet Archive)

Kawulich, B. B. (2005). Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Sozialforschung), 6(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.2.466

Lamerichs, N. (2018). Productive fandom: Intermediality and affective reception in fan cultures. Amsterdam University Press.

Lansdale, M. (1988). The psychology of personal information management. Applied Ergonomics, 19(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(88)90199-8

Lee, C. P., & Trace, C. B. (2009). The role of information in a community of hobbyist collectors. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(3), 621–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20996

Lee, L., Ocepek, M. G., & Makri, S. (2021). Creating by me, and for me: investigating the use of information creation in everyday life. Information Research, 26(1), paper 891. https://www.informationr.net/ir/26-1/paper891.html. (Internet Archive)

McKenzie, P. J. (2002). Communication barriers and information-seeking counter-strategies in accounts of practitioner-patient encounters. Library and Information Science Research, 24(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00103-7

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Oswald, W. & Schoepfle, G. M. (1987). Systematic fieldwork: Vol. 1. Foundations of ethnography and interviewing. Sage Publications.

Oulasvirta, A., & Sumari, L. (2007). Mobile kits and laptop trays: managing multiple devices in mobile information work. In B. Begole, S. Payne, E. Churchill, R. St. Amant, D. Gilmore, & M. B. Rosson (Eds.), CHI '07: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, United States, April 28-May 3, 2007 (pp. 1127–1136). Association for Computing Machinery. Price, L. (2017). Serious leisure in the digital world: Exploring the information behaviour of fan communities (Doctoral dissertation, City, University of London).

Prigoda, E., & McKenzie, P. J. (2007). Purls of wisdom: a collectivist study of human information behaviour in a public library knitting group. Journal of Documentation, 63(1), 90–114. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410710723902

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). The Free Press.

Rosenberg, R. S., & Letamendi, A. M. (2013). Expressions of fandom: findings from a psychological survey of cosplay and costume wear. Intensities: The Journal of Cult Media, 5(9), 9–18.

Ross, C. S. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783–799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00026-6

Savolainen, R. (2007). Information behavior and information practice: reviewing the “umbrella concepts” of information-seeking studies. The Library Quarterly, 77(2), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1086/517840

Spradley, J. P. (2016). Participant observation. Waveland Press.

Stebbins, R. A. (2009). Leisure and its relationship to library and: information science: bridging the gap. Library Trends, 57(4), 618–631. http://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0064

Suchman, L. A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: the problem of human-machine communication. University of Cambridge Press.

Talja, S., & Maula, H. (2003). Reasons for the use and non-use of electronic journals and databases: a domain analytic study in four scholarly disciplines. Journal of Documentation, 59(6), 79–101. http://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310506312

Vardell, E., Thomas, P., & Wang, T. (2020). Information seeking behavior of cosplayers. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 57(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.401

Vardell, E., Wang, T., & Thomas, P. A. (2022). “I found what I needed - a supportive community”: An ethnographic study of shared information practices in an online cosplay community. Journal of Documentation, 78(3), 564-579. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2021-0034