Abstract

Introduction. Extremism—distinct from activism—poses a serious threat to the healthy functioning of a society. In the contemporary world, the ability of extremists to spread their narratives using digital information environments has increased tremendously. Despite a substantial body of research on extremism, our understanding of the role of information and its properties in shaping extremist content is sketchy.

Method. To fill this gap, the current research has used ‘content analysis’ and ‘affective lexicon’ to identify and categorise terms from the publicly available online content of four extremists – two groups and two individuals. The property of information skewness provided the deciphering lens through which the categorised content was assessed.

Analysis. Contextual categories of information relevant to all the extremists were developed to analyse the content meaningfully. Six categories of religion, ideology, politics-history, cognition, affection, and conation provided the framework used to analyse and deductively categorise the data using content analysis. The affective lexicon developed by Ortony et al. (1987) was used to identify words belonging to the categories of cognition, affection (emotions and feelings), and conation (behaviour/actions).

Results. The findings reveal that the property of information skewness plays a significant role in shaping extremist content and two aspects of this property (a) intensity and (b) positivity or negativity can be used to (1) classify extremists into meaningful categories and (2) identify generalisable information strategies of extremists.

Conclusion. It was found that information skewness is used in the extremist content to produce the desired level of intensity and positivity or negativity. It was also found that intensity and positivity or negativity in information skewness can be used to categorise extremists into two categories: violent extremists (high intensity information skewness with positive bias) and violent extremists (high intensity information with negative bias).

Extremism represents a tendency to be close-minded, dogmatic, and averse to pluralism and minorities (Schmid, 2013). In a more acute form, it can include a willingness to use violence, mass atrocities, disregard for the law, and can take the shape of violent extremism. Extremism in any form creates an imbalance and takes away moderation. Depending on the magnitude and nature of the imbalance, various harms and problems can arise, which then can disturb the healthy functioning of a society. Extremism is not new but extremists’ ability to propagate their views and influence large numbers of people has been exponentially compounded due to the internet and social media (see Awan, 2017).

Extremists of all leanings (violent and non-violent) use information to promote their ideas and have followers to develop communities of like-minded people. The ability of groups and individuals to disseminate information in various forms and through a multitude of online and social media platforms has intensified the risk of extremism to an unprecedented level. Despite the preponderance of extremists and extremist content, our understanding of the role that different properties of information play in shaping such content is vague.

An important challenge associated with the afore-mentioned assertion is that not enough is known about the commonalities, if any, in the content of extremists. These gaps arguably are impeding the ability of national security agencies to effectively counter the threats of radicalisation and violence. It is hoped that this study will inform both the scholarly endeavors as well as the security agencies’ efforts to grapple with the challenges of radicalisation and violent extremism.

Extremism refers to views that are far from being moderate and intolerant of alternative viewpoints. Extremism originating from any kind of ideology can pose serious threats to the healthy functioning of a society. According to Saucier et al. (2009, p. 256), extremism can become violent if individuals holding such views start considering violence as a legitimate mean to achieve their goals. Extremist ideologies breed contempt and impair rational thinking. Ideas emanating from such ideologies, when they enter public spaces, provide an informational environment that influences thinking, emotions, and behaviour (Deci and Ryan, 2000; Ortony et al., 1987). Deci and Ryan argued that people get intrinsic motivation from their informational environment (p. 235). Due to their open access and vast reach, these environments are used by individuals, friends, foes, governments, making them a highly contested space. So, we see on one hand, extremists using this space to recruit like-minded people and on the other we see government agencies using a similar space for the surveillance of non-state actors, adversaries, and those posing threats to the rule of law. This reality of information environments along with their potentials and risks is acknowledged by many security agencies. The Australian Army’s varied research and strategic documents (Accelerated Warfare Statement, 2020b; Command Statement, 2020a; Department of Defence Information Warfare Strategy, 2020) acknowledge the importance of information in helping the Australian Army to respond to emerging challenges effectively. Hayward (2019) noted that non-state actors and individual agitators could use the information environment to carry out disruptive acts, ranging from accidental to emotionally and morally destructive. Similarly, Arquilla (2013) and Arquilla et al. (1999) argued that adversaries could use information networks to spread their message and cause cyber or physical damage. The Information Warfare Strategy of the Australian Department of Defence (2020) also acknowledges the highly contested nature of information environments and notes that they can be used by a range of actors, from criminals to nation-states.

Coupled with media affordances, flows of information can drastically sway opinions, leading even to national security threats (Afzal, 2016; Afzal and Wallis, 2016). Internet and social media provide opportunities for spreading extremist views to large audiences, with greater impact, and also with a possibility to maintain anonymity (Awan et al., 2019, p. 3). Owing to the potentially far-reaching implications of information on public perceptions, it is important to examine the role of different properties of information in shaping extremist content and identify generalisable strategies underlying extremists’ information warfare.

Information in its variety of forms (visual, verbal, and written) is an essential part of an individual’s environment and influences cognition (thinking), affect (emotions and feelings), and conation (behaviour/actions). Speaking to the wide-ranging impact of information, Deci (1975) reasoned that people use a wide array of information, including information from environment, memory, and internal states to make decisions (p. 93). Russell (2003) stated that our mood and emotions are influenced by the information we acquire. These informational contents are created by using different properties of information, including contextual, cognitive, affective, conative, qualitative, and quantitative factors.

Different properties of information come together to shape the overall quality of information and its impact on people. A substantial body of research has been developed within the disciplines of information science and information systems in the last three decades aiming to assess the overall quality of information. This research sheds light on the conceptual and operational aspects of information quality. According to Rieh (2002, p. 146), information quality is “the extent to which users think that the information is useful, current, accurate, and good”. Lee et al. (2002) developed an instrument to assess information quality, which conceptualised and operationalised 15 dimensions of information quality covering aspects of interpretability, objectivity, reputation, and understandability. Knight and Burn (2005) described various information quality frameworks and then identified 20 common dimensions of information quality, including accuracy, consistency, security, and timeliness.

These frameworks provide valuable guidance that can be used to argue that broadly speaking the properties of information can be classified into qualitative and quantitative categories. These two categories include the elements that shape the overall quality of information. In many cases, qualitative or quantitative properties can work independently of each other to shape the overall quality of an information piece; however, there are instances when a combination of quantitative and qualitative properties can make a piece of information greatly impact users’ thinking, emotions, feelings, and actions. It is also important to note that discerning the unique contribution of qualitative and quantitative properties of information to a piece of information can be complicated.

In terms of qualitative properties of information, dimensions such as usefulness, accuracy, completeness, relevance, objectivity, and readability have been found to be important influencers on users’ perceptions of information quality in several studies (see Oh and Worrall, 2013; Savolainen, 2011). Quantitative properties such as the amount of information and distribution of information have been studied more in economics, finance, and marketing. Properties such as incomplete information (Aboody and Lev, 2000), asymmetric information (Afzal et al., 2009), excessive information (Keller and Staelin, 1987), and the presence of positive and negative bias (skewness) in information have drawn the attention of scholars. This body of research also demonstrates that the quantitative properties of information influence thinking and behaviour.

The quantitative property of information used in this study to analyse extremist content was skewness. Skewness, statistically speaking, represents a distribution that is quantitively highly imbalanced (Keller et al., 1990). A distribution is around a mean, therefore, the imbalance can consist of values either greater or lower than the mean, making a distribution positively skewed in the case of the former and negatively skewed in the latter. It can be reasoned that ‘skewness’ represents a quantitative aftermath of an imbalance in objectivity/neutrality—a qualitative property of information. Hence, skewness embodies an interaction between a qualitative and a quantitative property of information. This notion of skewness in distributions can be applied to a flow of information. For instance, a deliberate attempt can be made to release information with overly positive connotations, thereby positively skewing information and vice versa (Afzal, 2015). It has been shown that skewness in information influences how we value a product (Afzal et al., 2009), estimate the worth of a service (Ajzen et al., 1996), and even perpetuate an organisational structure (Thompson and Wildavsky, 1986).

Though there is a sizeable body of research on quantitative and qualitative properties of information and there is also no scarcity of research on extremism, but still there is no clear understanding about the relationship between different properties of information and the extremist content. Furthermore, there is almost no research that sheds light on the common information patterns across extremist groups and individuals. Conway (2017) implicitly alluded to this gap when arguing for more research looking at the broad swath of extremist groups and across different media platforms. These gaps produce two interrelated research questions: (1) what is the role that properties of information play in shaping extremist content, and (2) are there any commonalities that can be identified in extremist content using properties of information? It is the aim of this study to make an attempt to answer these questions.

The answer to these questions can help identify generalisable information strategies of extremists and counter them using systematic information warfare aimed at protecting and manipulating (see Libicki, 1995) the information environment. Furthermore, the findings of this study will also help security agencies to better engage with the public in online information environments and to counter the threats of radicalisation.

The method of this study is informed by the understanding that information by virtue of its properties, the context in which it is used, and how it is organised and disseminated, influences human cognition, affect, and behaviour.

Extremism provides a context where information, coupled with online media and off-line contacts, plays a key role in influencing people. To analyse the informational content of extremists, the methodological framework of this study used the technique of ‘content analysis’. Content analysis was used to (1) identify themes in the data, (2) identify terms belonging to religious, ideological, political-historical, cognitive, affective, and conative dimensions, and (3) prepare the data for the assessment of information skewness. The work of Ortony et al. (1987) was used to identify terms that were cognitive, affective (emotions and feelings), and conative (behavioural or actions).

The identification of extremists was guided by the analysis of several key sources, including: the Australian Attorney-General’s Department List of Terrorist Organisations (https://www.ag.gov.au/national-security/australias-counter-terrorism-laws/terrorist-organisations), Southern Poverty Law Centre Extremist Files (https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files), the works of Holt et al. (2019) and Chermak and Gruenewald (2015), and public media news. The analysis was also informed by the underlying intent to have a diverse set of extremists to identify patterns and hence generalisable information strategies. Altogether four extremists were selected – two groups and two individuals (see Table 1). Publicly available online content of each of these extremists was found and an effort was made to select content that aimed at espousing the core ideas of each extremist. This approach was important to ensure consistency in data gathering and analysis across all extremists (see Table 2). Approximately 2000 words each were selected from the sourced data for each extremist, making the data set a little over 8000 words for analysis. The content was in the English language and textual, except that of Boko Haram, which was in their native language and in the form of videos. An English translation of Boko Haram’s videos was sourced using the services of the Site Intelligence Group (https://ent.siteintelgroup.com/about-site.html). In the case of Boko Haram, videos were selected because no textual content that could have been reliably linked to this group was found.

| No | Extremist Groups | Extremist Individuals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Islamic State (ISIS) | |

| 2 | Boko Haram | |

| 3 | Brenton Tarrant—Christchurch mass shooter | |

| 4 | Anders Breivik—Norway mass shooter |

Table 1: List of extremists

| No | Extremists | Sourced Data |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Islamic State (ISIS) | Dabiq Magazine |

| 2 | Boko Haram | Transcription of videos from the Site Intelligence Group |

| 3 | Brenton Tarrant—Christchurch mass shooter | Manifesto titled ‘The Great Replacement’ posted online available at https://img-prod.ilfoglio.it/userUpload/The_Great_Replacementconvertito.pdf |

| 4 | Anders Breivik—Norway mass shooter | Manifesto titled ‘2083-A European Declaration of Independence’ posted online available at https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid= |

Table 2: Extremist data

At first, contextual categories of information relevant to all these extremists were developed to analyse the content. The initial review of content denoted that ideas emanating from religion, ideology, politics, and history were defining the core arguments of extremists. In view of the close, and in many instances, seamless association between political and historical ideas in the content, it was decided to make one category representing both political and historical factors. The lexicon developed by Ortony et al. (1987) was used to identify words belonging to the categories of cognition, affection (emotions and feelings), and conation (behaviour/actions).

The six categories of religion, ideology, politics-history, cognition, affection, and conation provided the framework that was used to analyse and deductively categorise the dataset of each extremist. Two coders (the author and a research assistant) reviewed together the domain of each category and then undertook the first round of content analysis. Both coders met after the first round of coding to review the classification of words. Minor differences were observed which were resolved through discussion and elaboration on the rational used for classifying a particular word in a category. These discussions ensured consistency and uniformity in coding. A debriefing session was also held at the end of coding to review the complete categorisation. The content of every extremist (8000 words altogether; see Table 3 for sample content) was manually categorised into one of the six categories (i.e., religion, ideology, politics-history, cognition, affection, and conation). This analysis was done for all four extremists, resulting in the categorisation of 1925 out of 8000 words (see Table 4). These words embodied religious, ideological, political-historical, cognitive, affective, or conative elements.

| No | Extremists | Sample Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brenton Tarrant—Christchurch mass shooter | If there is one thing I want you to remember from these writings, its that the birthrates must change. Even if we were to deport all Non-Europeans from our lands tomorrow, the European people would still be spiraling into decay and eventual death. Every day we become fewer in number, we grow older, we grow weaker. In the end we must return to replacement fertility levels, or it will kill us. To maintain a population the people must achieve a birthrate that reaches replacement fertility levels. In the Western world this is roughly 2.06 births per woman. There is not a single Western country, not a single white nation, that reaches these levels. Not in Europe, not in the Americas, not in Australia or New Zealand. White people are failing to reproduce, failing to create families, failing to have children. Available at: https://img-prod.ilfoglio.it/userUpload/The_Great_Replacementconvertito.pdf |

| 2 | Anders Breivik—Norway mass shooter | But what exactly is “Political Correctness?” Marxists have used the term for at least 80 years, as a broad synonym for “the General Line of the Party.” It could be said that Political Correctness is the General Line of the Establishment in Western European countries today; certainly, no one who dares contradict it can be a member of that Establishment. But that still does not tell us what it really is. We must seek to answer that question. The only way any ideology can be understood, is by looking at its historical origins, its method of analysis and several key components, including its place in higher education and its ties with the Feminist movement. If we expect to prevail and restore our countries to full freedom of thought and expression, we need to know our enemy Available at: https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid= ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxicmVpdmlrcnVzaW5mb3J tfGd4OjM5NWY0MGJiYzAzYWY0N2E |

Table 3: Sample content

Following this analysis, the quantitative property of skewness (bias/extent of objectivity or lack of it) was assessed by assigning a weight between -1 to 1 to the categorised content. For this analysis, roughly the first 300 words were selected from the categorised content (i.e., 1925 words) of every extremist, thereby making a dataset of over 1200 words.

The weights, positive or negative, were assigned to the words in each category based on the following six criteria: a term signifying (1) an us vs. them scenario, (2) fear, impending demise, a sense of deadlock, hopelessness, (3) the presence of a fatal challenge to a so-called idealistic condition, (4) the glorification of an action or a situation requiring immediate action—a situation that has arisen due to the presumed betrayal of real values and ideology and/or invasion, (5) a heightened sense of identity of a person based on race, nationality, or religion, and (6) cognitive, affective, and behavioural appeals. These six aspects of the criteria were developed based on the initial review of the extremist data; the review revealed that the notion of identity, a heightened sense of us vs. them, and emotions of fear, hopelessness, or glory played an important role in shaping the extremist content and creating an overall message for the intended audience. A term having a moderate connotation pertaining to any of the six dimensions was given a weight of 0.5, whereas a term with explicitly extreme connotations was given a weight of 1.

Furthermore, depending on the context in which a term was used and the nature of the term itself, either a positive or negative weight was assigned. Then the skewness weights for each category and across all categories were calculated for every extremist (see Table 5). In calculating the total skewness weight, negative and positive signs of the weight were ignored, whereas these signs were considered in estimating the positive and negative intensity of the content.

It was clear from the analysis that the selected narratives of ISIS and Boko Haram mostly used religious terms (33.11% and 45.20%, respectively—see Table 4) in a highly positive way (95.5% of religious terms in ISIS content and 82.5% in Boko Haram’s content—see Table 5). On the contrary, Tarrant and Breivik’s narratives included many political-historical terms (46.23% and 28.04%, respectively—see Table 4) with highly negative connotations (82.6% of political-historical terms in Tarrant’s content and 95.6% in Breivik’s content—see Table 5).

Anders Breivik |

Brenton Tarrant |

ISIS | Boko Haram | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | % | No. of words | % | No. of words | % | No. of words | % | No. of words | Total words | % |

| Religious | 3.17 | 12 | 1.13 | 6 | 33.11 | 147 | 45.20 | 259 | 424 | 22.02 |

| Ideological | 17.46 | 66 | 3.40 | 18 | - | - | - | - | 84 | 4.3 |

| Political- Historical | 28.04 | 106 | 46.23 | 245 | 18.47 | 82 | 15.01 | 86 | 519 | 27 |

| Cognitive | 14.29 | 54 | 5.28 | 28 | 14.19 | 63 | 9.08 | 52 | 197 | 10.23 |

| Conative | 32.54 | 123 | 35.66 | 189 | 27.93 | 124 | 23.39 | 134 | 570 | 29.61 |

| Affective | 4.50 | 17 | 8.30 | 44 | 6.31 | 28 | 7.33 | 42 | 131 | 6.8 |

| Total | 100 | 378 | 100 | 530 | 100 | 444 | 100 | 573 | 1925 | 100% |

Table 4: Classification of content

| Categories | Extremists | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISIS | Boko Haram | Brenton Tarrant | Anders Breivik | |

| Religious | 22.5 [+21.5; ‑1] |

40 [+33; -7] |

- | - |

| Ideological | - | - | - | 9.5 [+2; -7.5] |

| Political-Historical | 8 [+1; -7] |

5 [+4; -1] |

37.5 [+6.5; -31] |

11.5 [+0.5; -11] |

| Cognitive | 6 [+5; -1] |

8 [+6; -2] |

0.5 [-0.5] |

8.5 [+5.5; -3] |

| Affective | - | 3.5 [+2.5; ‑1] |

- | - |

| Conative (action) | 33 [+32; -1] |

12 [+12] |

28.5 [+4.5; -24] |

17.5 [+5.5; -12] |

| Total weight | 69.5 | 68.5 | 66.5 | 47 |

Table 5: Skewness weights

A cross-comparison was also very interesting; for example, the total skewness weight for ISIS content was 69.5, whereas the skewness weight of Tarrant’s content was 66.5. It is important to note that though the skewness weights of these two extremists were similar, their internal composition was very different. ISIS’s skewness weight was mostly derived from terms (47.4%) that were inciting action, whereas a major portion of the skewness weight from Tarrant’s content (56.3%) was from political-historical terms. This finding points to the fact that a careful examination of content disseminated by each extremist is required to know the internal composition of content and how these seemingly benign and subtle components can shape content in a way that will have serious ramifications for shaping people’s thinking, emotions, feelings, and behaviour.

Both Tarrant and Breivik used a similar number of conative terms (35.66% and 32.54%, respectively) but the extent of negative skewness in these terms was very different (84.2% Tarrant and 69% Breivik), denoting an overly negative intensity in the case of Tarrant. It demonstrates that these weights provide an insight into the magnitude of intensity in the information and hence are important to consider.

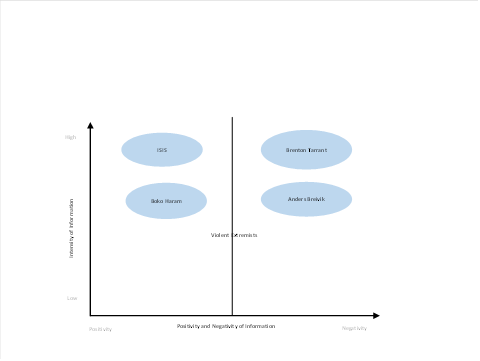

Following the above analyses, the findings emanating from each extremist were reviewed to identify commonalities and unique properties of information skewness underlying these four extremists. The findings showed that the current set of extremists could be classified into two categories using a two‑dimensional space: the two dimensions are the intensity of information and positivity-negativity of information. So, the two distinct categories based on the quality of information skewness: (1) high intensity skewness and positive information and (2) high intensity skewness and negative information (see Figure 1). The radicals classified in the high intensity skewness and positive or negative information categories can be termed as ‘highly violent extremists’ based on various factors. For example, a very high magnitude of intensity in information underpinning the content of these extremists, very highly biased information espousing either very positive or negative views, including the overall tone of their narrative embodying a very charged sense of us vs. them, a sense of high urgency in terms of taking violent action against the so-called threats whether in the form of government or individuals or socio-cultural forces, and the extent of skewness (bias) in their content encapsulating either a highly positive bias or a negative bias.

Figure 1: Classification of extremists

The analyses of all four datasets are revealing from many vantage points. For instance, the analyses revealed that the extremists have very significant common information skewness patterns along with highly important commonalities in their informational strategies. Specifically, the extremists who are really violent use either highly positively skewed or highly negatively skewed information coded with religion, political-historical, or ideological ideas. Another commonality in the content of these highly violent extremists is that their information primarily incites taking action and generally doesn’t invite much thinking. Groups like ISIS, Boko Haram and individuals like Tarrant and Breivik can be classified as violent extremists. All four are classified as violent extremists but belong to two spectrums of violent extremism – the first two belong to high intensity skewness and positive information, whereas the last two belong to high intensity skewness and negative information (see Figure 1).

The extent of skewness (bias) in content can have important implications for thinking, emotions, feelings, and behaviour. For instance, it has been shown in studies (Easterbrook, 1959; Mundorf et al., 1991) that a greater intensity of information coming from a source arouses emotions and narrows the attention of a person, thereby enabling them to focus on that source. However, at the same time, this heightened focus on one source along with emotions inhibits a person’s ability to pay attention to other sources present in the environment. Therefore, the intensity of information along with persistent exposure can lead to imbalanced viewpoints informed by a very limited set of sources and being oblivious to alternative viewpoints. In addition to the magnitude of intensity, the extent of positive and negative skewness in information should also be carefully examined to better understand skewness in content and its impact on cognition, affection, and behaviour.

ISIS and Boko Haram have been using primarily religious ideas to disseminate information that is highly positive in its impression. Additionally, the information presents a highly energetic and meaningful purpose that is waiting to be achieved, giving a strong message that their mission is a door to glory. On the contrary, Tarrant and Breivik used mostly political-historical and ideological ideas to disseminate highly negative information. Their information gives a very strong impression of inevitable and fast-approaching destruction. The only possibility for them is to take violent action against everybody, including migrants, the state, Islam, and people of colour to at least show courage in the face of these ever-destructive forces. Their information is in stark contrast to Boko Haram and ISIS as it paints a very dark future and primarily promotes hatred, fear, anger, demise, and destruction.

It is worth noting the extent of skewness (without considering positive or negative information) in the informational content of these extremists. This skewness was very high in ISIS, Boko Haram, and Tarrant’s content (69.5, 68.5, and 66.5, respectively) followed by Breivik’s content (47). If we consider the extent of positive and negative skewness in information, the highest percentage of negatively skewed content was by Tarrant (83.4%), followed by Breivik (72%) among the four violent extremists. ISIS’s content had the most positively skewed information (86%), followed by Boko Haram (84%).

Based on the analyses of informational content in this study, it can be argued that extremists can be classified into two categories: (1) Violent extremists with overly positively skewed information, information inciting urgent action – high on conation, information low on cognition, information presenting a highly energetic-purposeful-glorified mission; (2) Violent extremists with overly negatively skewed information, information inciting urgent action – high on conation, information low on cognition, information presenting a highly pessimistic and bleak future that cannot be averted but can be slowed by acting now.

There are at least three limitations of this study: (1) the dataset included a small number of extremists, (2) due to a need to categorise the terms manually, a limited amount of content was analysed, and (3) the content was mostly textual, except in the case of Boko Haram, and sourced from the Web precluding sources such as social media and public media. The last limitation becomes more pronounced when we consider the extremists who use more than one platform for propagating their views.

This study analysed the content of two extremist groups and two extremist individuals to identify (1) the role that information skewness plays in shaping extremist content and (2) the commonalities in extremist information warfare using information skewness as the deciphering lens. It was found that information skewness is used in the extremist content to produce the desired level of intensity and positivity/negativity. It was also found that intensity and positivity or negativity in information skewness can be used to categorise extremists into two categories: violent extremists (high intensity information skewness with positive bias) and violent extremists (high intensity information with negative bias).

The findings of this research has three key implications: (1) future avenues for research in the role of information and its properties in shaping extremist content and in influencing thinking, emotions, feelings, and behaviour will be opened, (2) the intellectual capital of security agencies will be enhanced by understanding the role of information skewness in shaping different kinds of extremist propaganda, and (3) security agencies will be better able to engage with the public in social media and more effectively cooperate with civil authorities to prevent acts of terror.

I acknowledge with thanks the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback. I am also grateful to Ammar Haider who assisted with data analysis.

This research was funded through grant #AARC 11/19 from the Australian Department of Defence.

Waseem Afzal is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Information and Communication Studies at Charles Sturt University. Waseem received his PhD and MBA from Emporia State University, Kansas – USA. He also holds a Master of Commerce in Finance from the Punjab University, Pakistan. His research interests focus on information behaviour, qualitative and quantitative aspects of information flow in social media, and on the role of information in shaping thinking, emotions, and feelings. He can be contacted at wafzal@csu.edu.au

Aboody, D. & Lev, B. (2000). Information asymmetry, R&D, and insider gains. Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2747-2766. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/0022-1082.00305

Afzal, W. (2016). A study of the informational properties of the ISIS’s content. Proceedings of the 79th ASIS&T Conference, 53(1), 1-10. https://asistdl.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301056

Afzal, W. & Wallis, J. (2016). Informational properties of extremist content: an evidence-based approach. Australian Army Journal, XIII(2), 67-90. https://search.informit.org/doi/pdf/10.3316/informit.673263594698137

Afzal, W. (2015). Towards the general theory of information asymmetry. In M. M. Al-Suqri & A. S. Al-Aufi (Eds.), Information seeking behavior and technology adoption: theories and trends (pp. 124–135). IGI Global.

Afzal, W., Roland, D. & Al-Suqri, M. (2009). Information asymmetry and product valuation: An exploratory study. Journal of Information Science, 35(2), 192-203. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0165551508097091

Ajzen, I., Brown, T. C. & Rosenthal, L. H. (1996). Information bias in contingent valuation: effects of personal relevance, quality of information, and motivational orientation. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 30, 43-57. https://web.archive.org/web/20230511/https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_other/rmrs_1996_brown_t003.pdf (Internet Archive)

Arquilla, J. (2013). Twenty years of cyberwar. Journal of Military Ethics, 12(1), 80-87. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15027570.2013.782632

Arquilla, J., Ronfeldt, D. & Zanini, M. (1999). Networks, netwar, and information-age terrorism. In Z. Khalilzad, J. P. White & A. Marshall (Eds.), Countering the new terrorism (pp. 75-111). RAND.

Attorney-General’s Department. (n.d.). List of terrorist organisations.

https://web/archive.org/web/20230511051913/https://www.ag.gov.au/national-security/australias-counter-terrorism-laws/terrorist-organisations (Internet Archive)

The Australian Army. (2020a). Army in Motion – Command Statement by Chief of Army. /web/20230508022041/https://www.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/2020%20Command%20Statement_2.pdf (Internet Archive)

The Australian Army. (2020b). Army in Motion – Accelerated Warfare Statement by Chief of Army. https://web/archive.org/web/20230508022647/https://www.army.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/2020%20-%20Accelerated%20Warfare_0.pdf (Internet Archive)

Awan, I., Sutch, H. & Carter, P. (2019). Extremism online: analysis of extremist material on social media. https://web/archive.org/web/20230511052218/https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/834369/Awan-Sutch-Carter-Extremism-Online.pdf (Internet Archive)

Awan, I. (2017). Cyber-extremism: ISIS and the power of social media. Society, 54, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-017-0114-0

Chermak, S. & Gruenewald, J. (2015). Laying a foundation for the criminological examination of Right-Wing, Left-Wing, and Al Qaeda-Inspired extremism in the United States. Terrorism and Political Violence, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.975646

Conway, M. (2017). Determining the role of the Internet in violent extremism and terrorism: Six suggestions for progressing research. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(1), 77-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2016.1157408

Deci, E. L. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Department of Defence (2020). Information Warfare Strategy. https://web/archive.org/web/20230511052803/https://www.dst.defence.gov.au/strategy/star-shots/information-warfare (Internet Archive)

Easterbrook, J. A. (1959). The effect of emotion on cue utilization and the organization of behavior. Psychological Review, 66(3), 183-201. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047707

Hayward, L. (2019). Future joint force information warfare operations – Part 1. https://web/archive.org/web/20230511053041/https://researchcentre.army.gov.au/library/land-power-forum/future-joint-force-information-warfare-operations-part-1 (Internet Archive)

Holt, T. J., Stonhouse, M., Freilich, J. & Chermak, S. (2019). Examining ideologically motivated cyberattacks performed by Far-Left groups. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(3), 527–548. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09546553.2018.1551213

Keller, K. L. & Staelin, R. (1987). Effects of quality and quantity of information on decision effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 14, 200-213. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1086/209106

Keller, G., Warrack, B. & Bartel, H. (1990). Statistics for management and economics (2nd ed.). Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Knight, S-A. & Burn, J. (2005). Developing a framework for assessing information quality on the World Wide Web. Information Science Journal, 8, 160-172. https://web/archive.org/web/20230511053315/http://inform.nu/Articles/Vol8/v8p159-172Knig.pdf (Internet Archive)

Lee, Y. W., Strong, D. M., Kahn, B. K. & Wang, R. Y. (2002). AIMQ: A methodology for information quality assessment. Information & Management, 40, 133-146. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378720602000435

Libicki, M. C. (1995). What is information warfare? https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA367662.pdf

Mundorf, N., Zillmann, D. & Drew, D. (1991). Effects of disturbing televised events on the acquisition of information from subsequently presented commercials. Journal of Advertising, 20(1), 46-53. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00913367.1991.10673206

Oh, S. & Worrall, A. (2013). Health answer quality evaluation by librarians, nurses, and users in social Q&A. Library & Information Science Research, 35(3), 288-298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2013.04.007

Ortony, A., Clore, G. L. & Foss, M. A. (1987). The referential structure of the affective lexicon. Cognitive science, 11(3), 341-364. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1207/s15516709cog1103_4

Rieh, S. Y. (2002). Judgment of information quality and cognitive authority in the web. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 53(2), 145-161. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/asi.10017

Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110(10), 145-172. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-295X.110.1.145

Saucier, G., Akers, L. G., Shen-Miller, S., Kneževié, G. & Stankov, L. (2009). Patterns of thinking in militant extremism. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(3), 256-271. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01123.x

Savolainen, R. (2011). Judging the quality and credibility of information in Internet discussion forums. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1243-1256. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/asi.21546

Schmid, A. P. (2013). Radicalisation, de-radicalisation, counter-radicalisation: A conceptual discussion and literature review. ICCT research paper, 97(1), 22 https://web/archive.org//web/20230511053604/https://www.exit-practices.eu/uploads/1/3/0/4/130474014/schmid_a.__2013_.pdf (Internet Archive)

Site Intelligence Group. (n.d.). The search for international terrorist entities. /web/20230511054013/https://ent.siteintelgroup.com/ (Internet Archive)

Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). Extremist files. https://web/archive.org//web/20230511054136/https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files (Internet Archive)

Thompson, M. & Wildavsky, A. (1986). A cultural theory of information bias in organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 23(3), 273-286. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1986.tb00954.x