Information Research

Vol. 29 No. 3 2024

Antivaccine, denialist, and conspiracy theorist content on Facebook. An analysis of the No to the New World Order page

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir293693

Abstract

Introduction. Antivaccine, denialist, and conspiracy ideas are generally part of an ecosystem of beliefs reinforcing each other. With the advent of covid-19, these ideas figure among the main disinformation contents of counter-official discourses. The article aims to characterize the contents of the Facebook page ‘No to the New World Order’.

Method. The content analysis method was employed for the 625 publications on the page during the period studied (October 2020 to January 2022).

Analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis, the topic modeling technique, and the Latent Dirichlet Allocation algorithm.

Results. Covid-19 was the main focus of the analysed posts (68%). Many posts criticised government measures, while others alleged censorship and media manipulation of unofficial covid-19 information. Additionally, the posts asserted that the pandemic is part of a New World Order promoted by elites. Conservative ideas were also found, alongside the criticism of health, economic, and financial organisations. The most liked posts included two videos: one about a strike by health workers in France and another criticising vaccines.

Conclusions. Based on the published content, it can be observed that 'No to the New World Order' serves as a platform for criticizing pandemic management across all fronts. However, this space does not accommodate divergent opinions, criteria, or perspectives, nor does it offer criticism or questioning of the accuracy of shared content. These conditions foster misinformation and polarization on the issue.

Introduction

The digitalisation of the public space has made the search for and prevalence of truth increasingly complex (Innerarity and Colomina, 2020). It occurs partly because the average citizen relies on trusted sources that align with their views and ideology (Valera-Orgaz, 2017). As advocated by the theory of motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990), we are positively predisposed to information that ratifies pre-existing beliefs, while it is easier to reject information that contradicts us. For example, opponents of vaccination will seek out information that reinforces their anti-vaccine ideas. And, in the sea of information and misinformation on the internet, this is not difficult.

On social networks, it is possible to decide who to debate with and who not to. This creates information bubbles that group internet users based on their similarities, while disconnecting them from those who think differently (Boxell et al., 2017), thus avoiding exposure to divergent ideas (Prior, 2007). As social identity theory (Tajfel, 1984) points out, subjects tend to classify themselves into social groups, which leads to the acceptance of the norms and values of their group. This leads to a comparison with others, where there is a positive valuation of one's group and a negative valuation of others. This sense of belonging and identification with a group accentuates political and social polarisation, because they are not interested in scientific evidence, but rather only seek to reinforce and disseminate their ideas. This makes it very difficult to achieve a real social debate on any topic in the digital public sphere.

According to Prior (2013), this selective exposure to information leads to negative polarisation, because it reinforces subjects' previous values, attitudes and behaviour. When we are immersed in a bubble where our ideas are dominant, our positions are radicalised (Reese et al., 2007). This leads to a saturation of content with a single perspective, which forms an ecosystem that favours disinformation, fragmentation and political polarisation (Bennett and Livingston, 2018). This is what is known as the 'post-public sphere', referring to the proliferation of increasingly extreme and radical positions in the digital sphere (Davis, 2019).

In highly polarized contexts, debates about government actions are often marred by misinformation, or at least manipulated information. Social discourse frequently revolves around political or ideological disputes brought about by polarization rather than the well-being of populations. For instance, during the covid-19 crisis, much of the circulating information did not aim to educate about virus risks or preventive healthcare measures. Instead, it often sought to sway public opinion against government decisions and actions (Robles et al., 2022). This led to the emergence of digital spaces ranging from staunch opposition to any government action to outright denial of the existence of the coronavirus.

There is a parallel between antivaccine, denialist, and conspiracy theorists. Some authors have argued that being against vaccination brings sympathy for other ideas (Bertin et al., 2020). These concomitances give clues to the ecosystem of ideas around the issue, allowing us to understand the arguments and logic that sustain them in a broader sense.

Brotherton (2013) characterizes conspiracy theories in context, content, and epistemology. In context, he notes that they are unconfirmed claims, often less plausible explanations than the official ones, and are loaded with sensationalism. In terms of content, it is understood that everything that happens is causal and intentional, and they mask malevolent intentions. Epistemologically, they are unreliable because they are based on very little or inconsistent evidence and are not the result of scientific debate. Any questioning of their theories is understood as an attack to destabilize them. These groups understand that everything is orchestrated by supernatural powers or the elites trying to rule the world. These elites are governments, scientists, prominent business people, or millionaires (Soler-Roca, 2022).

One of the critical topics of conspiracy theories in recent times has been vaccination, long before covid-19 (Lewandowsky et al., 2013). Despite being proven that vaccines are one of the scientific advances that have significantly impacted the population's life expectancy, a movement has emerged that totally or partially discredits their use (Salmeron Henríquez, 2017). Other studies have found vaccination as the main topic (42% of the total) of fake news to be disproved by verification agencies during the pandemic in Mexico (Aguila Sánchez and Pereyra-Zamora, 2022). This situation has gained so much traction that antivaccine is considered by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2022) as one of the main threats to public health. With the pandemic, vaccines, mobility restrictions, and the use of masks, among other measures taken by governments in response to the health crisis, are also being questioned. Their criticism is based on the loss of individual liberties that this implies or their resemblance to measures taken by dictatorial regimes.

Before covid-19 vaccination, it was already expected that ‘attitudes toward this future vaccine did not follow the traditional mapping of political attitudes along a Left-Right axis’ (Ward et al., 2020, p. 1). The authors note that ‘people who feel close to governing parties (Center, Left, and Right)’ would be more in favour. In contrast, ‘people who feel close to the Far-Left and Far-Right parties, as well as people who do not feel close to any party’ would be more against it (Ward et al., 2020, p. 1).

Dubé et al. (2021, p. 180) point out that ‘the more political side of vaccine criticism is often reduced to conspiracy theories and radical denial of the legitimacy of the state to intervene in private citizens' health.’ According to these authors, ‘pharmaceutical companies today are at the centre of these conspiracy theories, which reflects changes in the world of vaccines’ (p. 180).

Although the spread of hoaxes or conspiracy theories is a minority issue, it can cause significant damage by hindering measures that demand collective action, such as herd immunity or using the mask to contain the virus (Soler-Roca, 2022). It happens because, despite being a minor group issue, ‘is further amplified and made visible online’ (Smith and Graham, 2019, p. 1323). Likewise, other study finds that although vaccine advocates have more followers than antivaccine advocates, the latter tend to use social networks more effectively (Gargiulo et al., 2020).

The study is on the Facebook page No to the New World Order. A Facebook page is analysed for several reasons. First, studying social networks allows us to understand what happens in real life. According to Smith and Graham (2019) there is an analogy between antivaccine social networks and social movements in real life. Also, it is a page with open access. That is, it allows accessing its contents without restrictions. In addition, the administrators must approve the publications. In this way, access is given to a sample of publications that should represent the page's ideas.

On the other hand, a page in Spanish is studied to understand how the phenomenon occurs in the Spanish-speaking world. Ward et al. (2015, p. 1063), state that ‘English language Antivaccination websites have been thoroughly analysed. However, little is known of the arguments presented in other languages on the internet.’

Then, the article aims to characterise the contents of the No to the New World Order page. The research question is: What is the interrelation between the denialist, conspiracy, and antivaccine contents? The study establishes the research hypothesis that there is a close relationship between anti-vaccine, conspiracy, and denialist themes. This study contributes to understanding how the pandemic denialist phenomenon is intertwined with antivaccine ideas and conspiracy theories. In addition, the study allows us to explain the communicative and discursive mechanisms in social networks to disseminate these ideas.

About the characterisation of the page, we adopted indicators used by other authors. First, a review of formats (written texts, images or videos) and information resources in the posts was made (Boyd, 2010; Starbird, 2021). Also included an analysis of government measures that have been criticised, as well as the alleged manipulation and censorship of information circulated against vaccines (Roman-san-miguel et al., 2020; Soler-Roca, 2022). Conspiracy explanations for covid-19 pandemic were also explored (Douglas, 2021). Finally, the infiltration of conservative ideology in these posts (Vosoughi, 2018) and the resonance in social networks based on direct interactions (like, comment and share) are analysed as an indicator that internet users pay attention to the information and even incite others to react to the post (Reig Alamillo and Elizondo Romero, 2018; García et al., 2024).

Methods

A content analysis was performed on the No to the New World Order page. It is a study that employs quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The 625 publications on the page from October 2020 to January 2022 were analysed.

The page

No to the New World Order is a Facebook page aimed at sharing denialist and antivaccine ideas in the broad framework of an offensive against Agenda 2030 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. This page was created in 2020, and it has more than 5000 likes, more than 5600 followers, and a stable rate of publications: it publishes almost daily. Six hundred twenty-five publications, 20,571 likes, and 1,937 comments were found during the study period. These elements support the page transcendence and validity as a space for disseminating denialism, conspiracy theories, and antivaccine ideas.

The page says that it is administered from Mexico City, but, being in Spanish, it becomes a communication space for denialism in the Spanish-speaking world in general. This is evident because the language they use. For example, some publications used mascarilla, others cubrebocas, and some barbijo, three different ways of calling the same thing (mask) in Spain, Central America, and South America. After an external review of several similar pages, it was decided to analyse only one page because similar contents are repeated in all the others.

Instruments and variables

For the content analysis, a guide was prepared to classify the posts. The variables and categories analysed are shown in Table 1. Some were fixed beforehand, and others were incorporated along the way.

| Data block | Variables | Codes and categories obtained |

|---|---|---|

| Registration | Registration No. | Number |

| Full owner | Free text | |

| Date of publication | Day-Month-Year | |

| Format | Photo, video, news, text only, audio | |

| Source | Free text | |

| Verification | Yes or no | |

| Total likes, comments, and shared | Number | |

| Haha, or angry is the most common | Number | |

| Contents | Institutional anti-measures | Against vaccinations, masks, and mobility restrictions. |

| Conservative political and sexual values | Nationalism, anti-communism, anti-socialism, anti-left. Anti-LGBTQ+ and women's rights, anti-abortion. Religious ideas. | |

| Conspiratorial language | New World Order, Agenda 2030, elites, depopulation, chips, globalism, plan-demia, transhumanism, DNA, 5G. | |

| Attacks for complying with measures | Sheeple, slaves, muzzles | |

| News of rebellion | Yes or no | |

| Contradicts the ideas of the page | Yes or no | |

| Indoctrination | Media manipulation, network censorship | |

| Other contents | Esoteric, grotesque, humour, infants, dictatorships | |

| Subjects and organizations | Public figures cited | Names |

| Criticized organizations | ||

| Criticized politicians | ||

| Politicians praised |

Table 1. List of variables, codes and categories of the study

Data analysis

Six hundred twenty-five publications, dated between October 2020 and January 2022, were analysed. The information resulting from the analysis was organized in an Excel® database. Descriptive statistics were applied to calculate percentages and contingency tables. This analysis used SPSS v.26® statistical software. For the qualitative analysis, Atlas.ti® was used to categorize the terms used in the discourse of the page. The Kappa index (k=.98) was also calculated to analyse the concordance in the data classification.

In addition, the topic modelling technique was used, which represents a statistical method to find out those abstract topics within a given selection of documents or now, in websites. This method is usually applied in text mining as it is used to discover those semantic structures hidden in the textual data. Themes are thrown up following the recurrence of words related to that theme, assuming that they refer to the same semantic domain (or topic).

Topic models, are known as probabilistic methods, referring to the application of statistical algorithms to find the latent semantic structures within a large text. This method helps to organize and provide information in a more practical and segmented way.

The Latent Dirichlet Allocation algorithm was used about databases that are not catalogued as metadata. This model automatically assigns each analysed word a probabilistic score on the most probable or closest topic to which it may belong.

In addition, the Orange software was used, as it specialises in data mining and predictive analysis. It is supported by several components developed in C++, which implement algorithms; data mining, processing operations, and graphical representation can be applied. The components of such software can be manipulated through the Python program or, in turn, in a graphical environment.

Limitations

One limitation of the study is that it does not analyse antivaccine discourses directly from the subjects but analyses their Facebook posts. Although these publications contain their discourses, elements not included therein may be missed. Therefore, it is recommended to interview antivaccine people to deepen the findings of this study.

Results

The publications were analysed according to the variables of the study (Table 1): general characteristics, governmental measures against covid-19, media manipulation and censorship, conspiracy and conservative ideas, subjects and organizations, interactions on the page, and other content. The results of the applied topic modelling technique are shown at the end.

General characteristics of the publications

Of the 625 publications, 68% were related to covid-19. The main format was video (46%), followed by images (38%) and news (12%). The months of highest publication were January (29%) and February (29%) of 2021. More than a third (39%) of posts were shared from other sites. The primary sources were other social networks such as Telegram (35%) and YouTube (5%). The most shared digital news outlet was SDP Noticias (8%), and the TV station was Russia Today (4%). Of the 625 publications collected, only 3% had a Facebook warning about falsehood or decontextualization of their content.

Governmental measures against covid-19

Posts against institutional measures stand out, such as restrictions on mobility (34%), including the closure of regions or implementation of health passes or passports. For example, one post said: ‘These politicians no longer know what to invent to continue depriving citizens of their liberties.’ There is also intense criticism of vaccination (33%) and the use of masks (23%). 13% of the posts had content of rebellion against the measures, generally videos of street protests. 7% of the posts incited to rebel by taking these measures such as not getting vaccinated or taking to the streets to protest.

Media manipulation and censorship

One-third (31%) of the posts on the page criticized the handling of information during the pandemic, either because of the alleged media manipulation (19%) or because of censorship in social networks (11%). Thus, statements such as ‘They are not journalists, they are puppets who misinform and spread fear’ or ‘The singer León Larregui has just been suspended from Twitter after giving his opinion about vaccines against covid-19’ appear.

Likewise, 20% of the posts mentioned dictatorship, and 14% used indoctrination to refer to the excluded content in the media, networks, and institutional and official discourses. On the other hand, 11% of the posts contained attacks on people who thought differently from the ideas of the page. It was common for the mask to be called a muzzle (7%) and for those who wore it to be called sheep (7%). No post was found against denialism or questioning conspiracy theories, and none was found favouring vaccines, using masks, or any institutional measure.

Conspiracy ideas

Some of the conspiracist ideas are ‘the new normal imposed by the Elites,’ ‘the plot of a new order,’ and ‘Agenda 2030. Goals of Depopulation’. These posts claim that the pandemic is part of a New World Order (69%), promoted by the elites (26%), which will be implemented through the Agenda 2030 (14%), which has among its goals global depopulation through genocide (9%).

Other conspiracy statements were: ‘Let us not let us put any vaccine, and especially no chip,’ ‘Transhumanism and the internet of things,’ ‘Plan-demia, what is the point of creating a crisis?’ or ‘These vaccines of today and the 5G’. These posts claimed that vaccines contain nanotechnology (6%) and that they seek to develop transhumanism (6%) with it. In 15% of the posts, plan-demia is mentioned, and in 4%, vaccination is related to 5G technology.

Conservative ideas

Some conservative ideas (10%) were also found in the political and sexual areas. Examples of posts with nationalist and anti-communist ideas are: ‘Last Minute: In Spanish farewell speech President Trump’ and ‘The great reset concludes with the Imposition of Communism.’ Others were against LGBTQ+ groups and women's rights, especially abortion: ‘I was born a dog, but thanks to gender ideology, I am a bird’ or ‘The heart of an aborted baby.’ The idea that vaccines are made with cells from aborted fetuses is shared. Other publications promote the parental pin that gives power to the family to decide the education children receive at school and thus avoid the ‘indoctrination of gender ideology.’ Several publications are dedicated to anal polymerase chain reaction examinations, which are presented as a ‘humiliation to human dignity.’

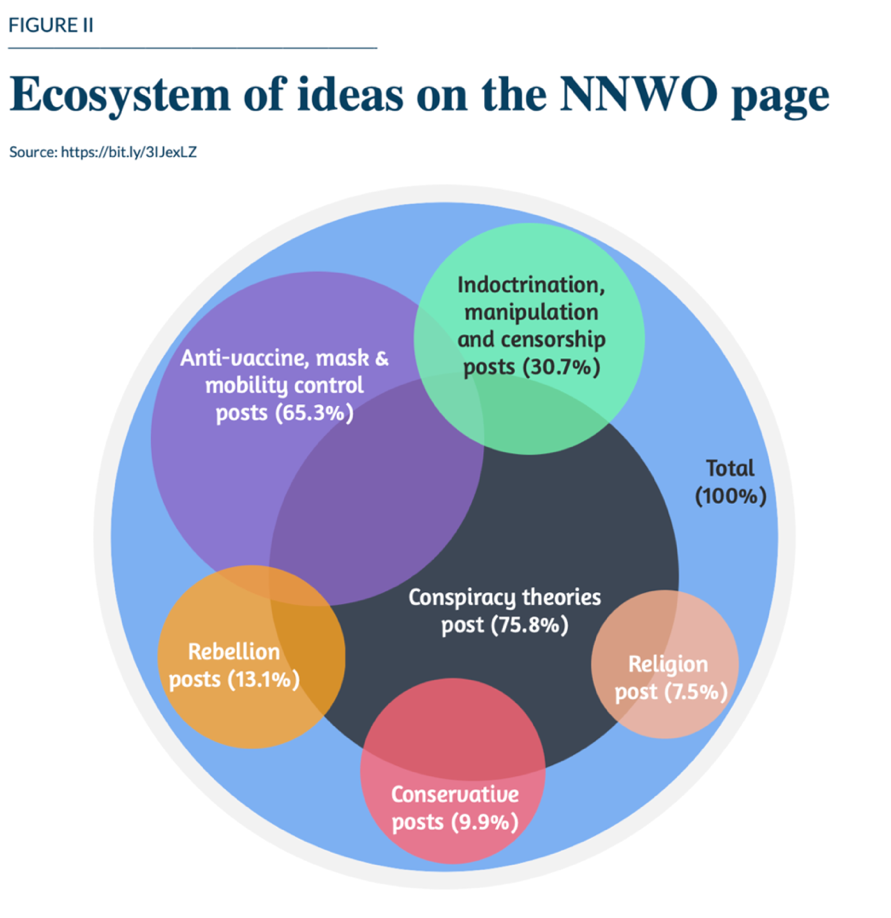

Mentioning God (8%) or speaking in religious terms (e.g., biblical, apocalyptic, divine, punishment) was also recurrent. An example of sympathizing with conservative ideas is a post where they claim that the New World Order was defeated, and the heroes of the story are Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and Marine Le Pen, three conservative politicians who have systematically opposed the rights of migrants, women, and LGBTQ+ groups. Anti-Brexit and pro-gun posts are also found. Others deny climate change, seeing it as a strategy to impose a global dictatorship. Figure 1 depicts the ecosystem of ideas found in the publications on the page.

Figure 1. The ecosystem of ideas on the page

Criticism of Subjects and Organizations

There was also strong criticism of health and economic or financial organizations. An example of these publications is that ‘In Germany, Commerzbank is considering closing the accounts of customers who do not have the covid passport from 2022. Politicians applaud.’ Of the total number of organizations criticized, the World Health Organization (39%), the International Monetary Fund (10%), the World Economic Forum (8%), and the World Bank (6%) stand out, and to lesser extent, the European Union, the Mexican Health Secretariat, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Mastercard, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) or the US Food and Drug Administration. For example, another post claims that the International Monetary Fund offers economic aid to the President of Belarus (Aleksandr Lukashenko) in exchange for imposing confinement in his country, and he refuses. However, the most criticized figure was Bill Gates (33%), for being considered the architect of the pandemic.

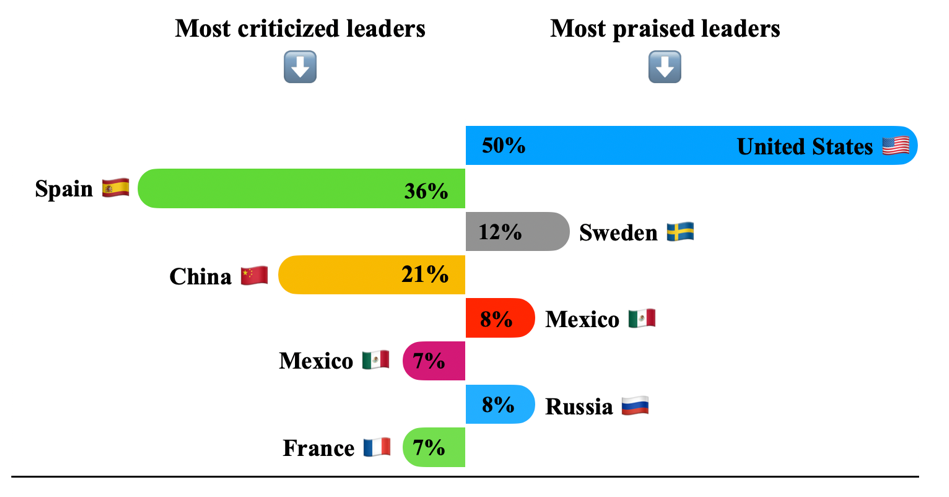

On the other hand, among the posts that criticised political leaders, 36% contained attacks on Pedro Sánchez (Spain), 21% on Xi Jinping (China), and 7% on Andrés Manuel López Obrador (Mexico). On the other hand, of the positive posts relating to political leaders, 50% stands out for Donald Trump (United States), as the most praised. He is followed by the rulers of Sweden (12%), who were considered an example because of the few restrictions they imposed to covid-19 situation. Then there was Vladimir Putin (Russia) and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (Mexico) again, with 8% of the total positive reviews, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Most criticized and praised leaders

Interactions

Anger was found to be the most common reaction in 61 posts. These were mainly about mobility restrictions (30%), vaccination (26%), and mandatory facemask (25%). Another part was posts on the application of measures on children (15%) or police violence (5%). Among the most shared on the page is one explaining the New World Order and another on implementing the covid passport (both six times shared). They were followed by one criticising the government of Spain for closing local businesses and leaving supermarkets open, and another criticising the ‘prostituted media’ (both four times shared).

Also, the most liked were a video about a strike of health workers in France (371 likes) and a criticism of vaccines (295 likes). This criticism is based on personal experience: ‘They are already on their third dose, fourth wave, strain twelve, and I have not even heard about it, much less gotten sick of anything. My health is in perfect STATE’. The most commented was ‘dictatorship measures vs covid measures’ (40 comments), in which similarities between these two scenarios are established. It is followed by ‘The Vatican gets tough on antivaccine’ (37 comments), where they show themselves attacked by the Catholic church. Furthermore, the third most commented on is ‘Jennifer, daughter of Bill Gates, gets vaccinated against covid-19 and mocks conspiracies’ (35 comments), where the followers of the page support each other for being considered conspiracy theorists.

Other content

Three per cent of the posts contained other exciting ideas to analyse. Among them was criticism of the pharmaceutical industry, junk food, transnational companies, market monopolies, economic powers (the International Monetary Fund, and banks), and paedophilia in the Catholic Church and in general. Another detail is that some posts talked about children (5%), especially the effects of vaccination and other measures on this population group. There is also a coexistence between mentioning childhood and requesting financial support to maintain the page; this happens in all the posts (8) that ask for help.

On the other hand, only 3% of the posts were humorous, and 1% had grotesque content, such as videos of people dying from the vaccine. Only 1% dealt with esoteric topics such as karma, supernatural powers, consciousness-raising, or bioenergy. Although to a lesser extent, there is also criticism of the work of verification agencies, and on a few occasions, Julian Assange's phrases against the media were shared. There is also a promotion of traditional medicine as a more sustainable alternative to relying on and promoting the pharmaceutical industry.

Topic modelling

For the evaluation of the topic model, applying the Latent Dirichlet Allocation algorithm, eight categories of topics were assigned, which were classified as anti-institutional measures, conservative political and sexual values, conspiratorial language, attacks for complying with measures, news of rebellion, contradicts to the ideas of the page, and indoctrination, among others.

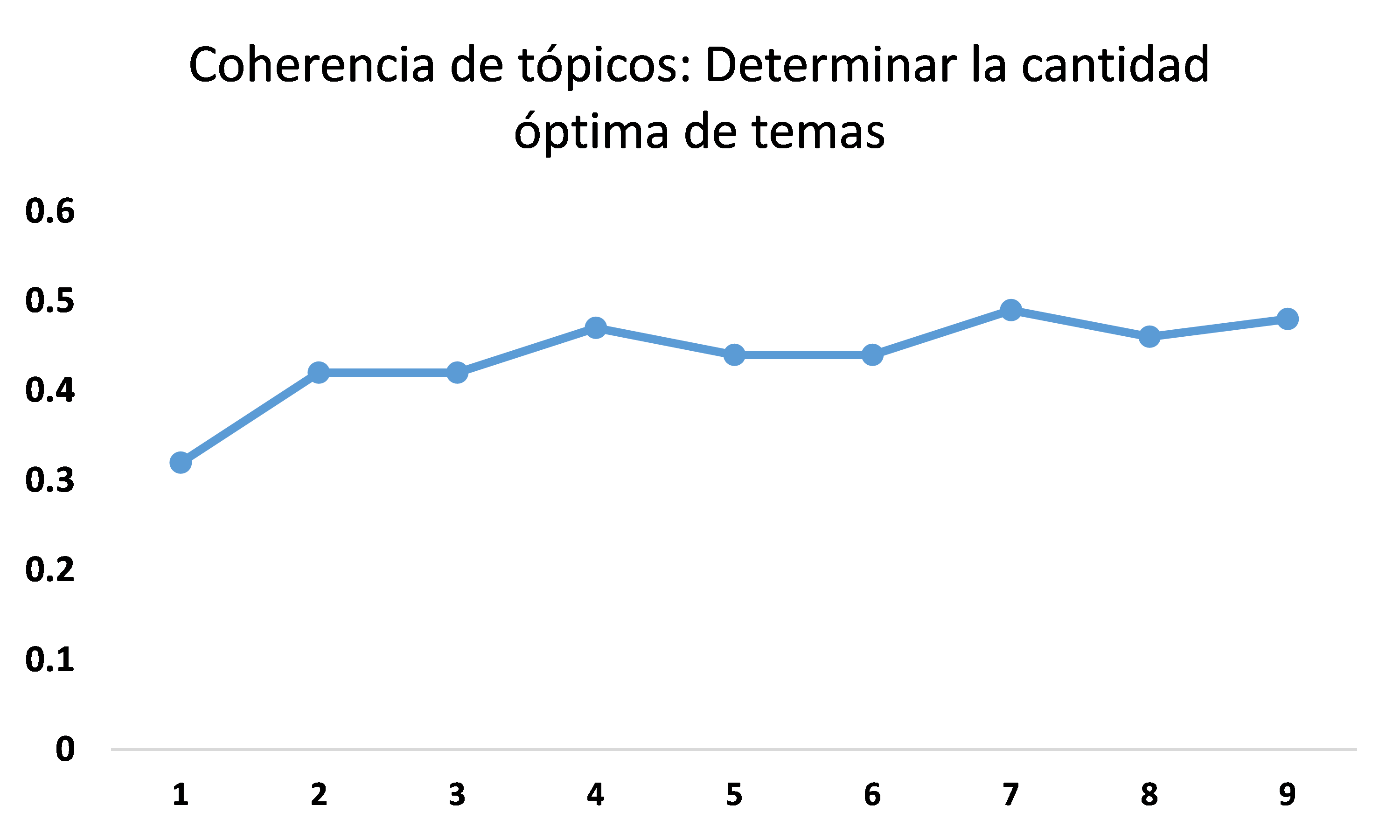

To determine the number of topics, Figure 3 describes the coherence score. The x-axis is for the fixed alpha, whose values are plotted within 0.01 to 0.1, while for the y-axis, the number of topics in validation is plotted. As it is observed, the coherence score increases as more topics are selected. The highest score is in topic seven, with 0.49 coherence, while the alpha indices are 0.61. This means further data clustering categorizes the topic model into seven topics.

Figure 3. Coherence of topics. Determining the optimal number of topics

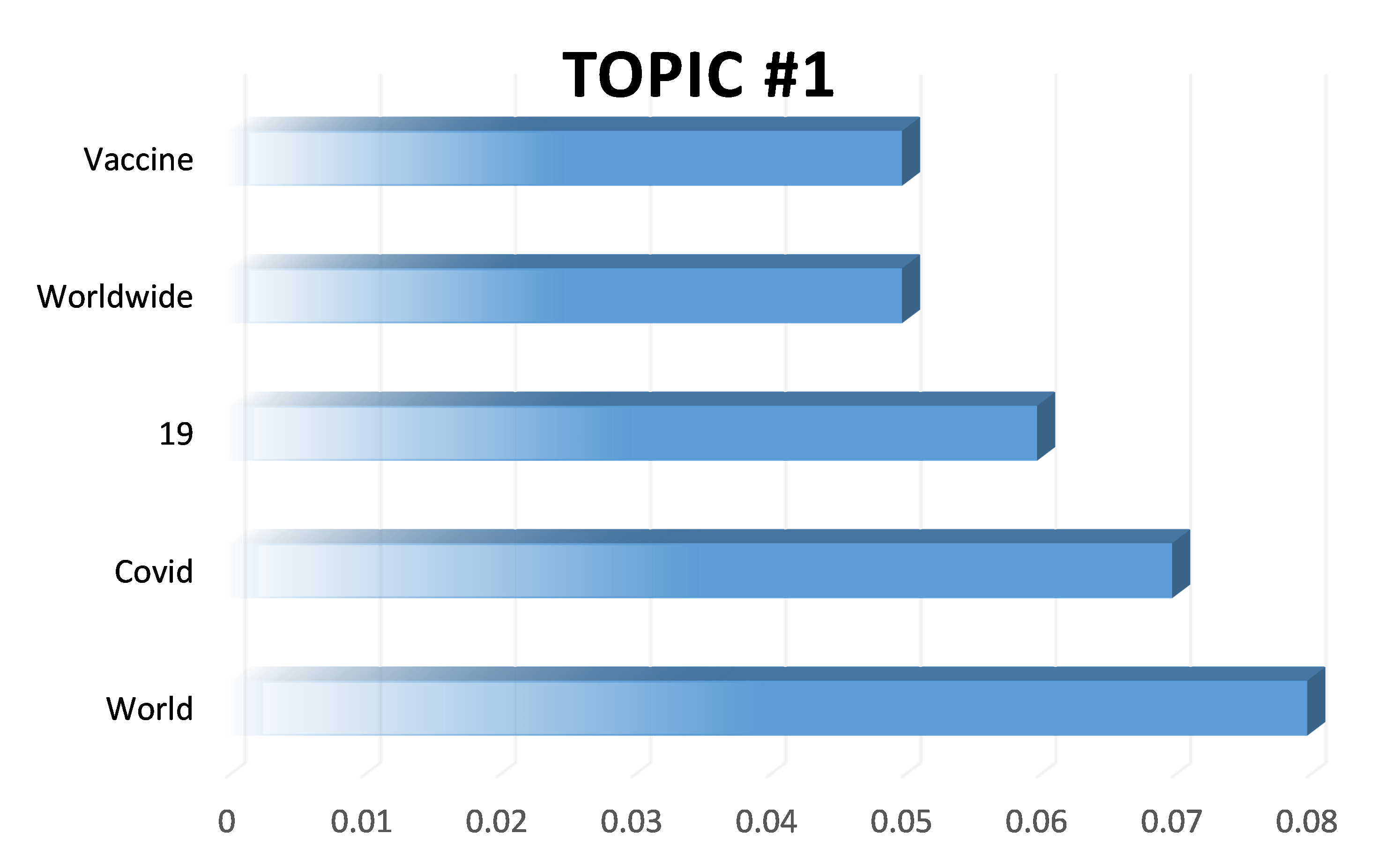

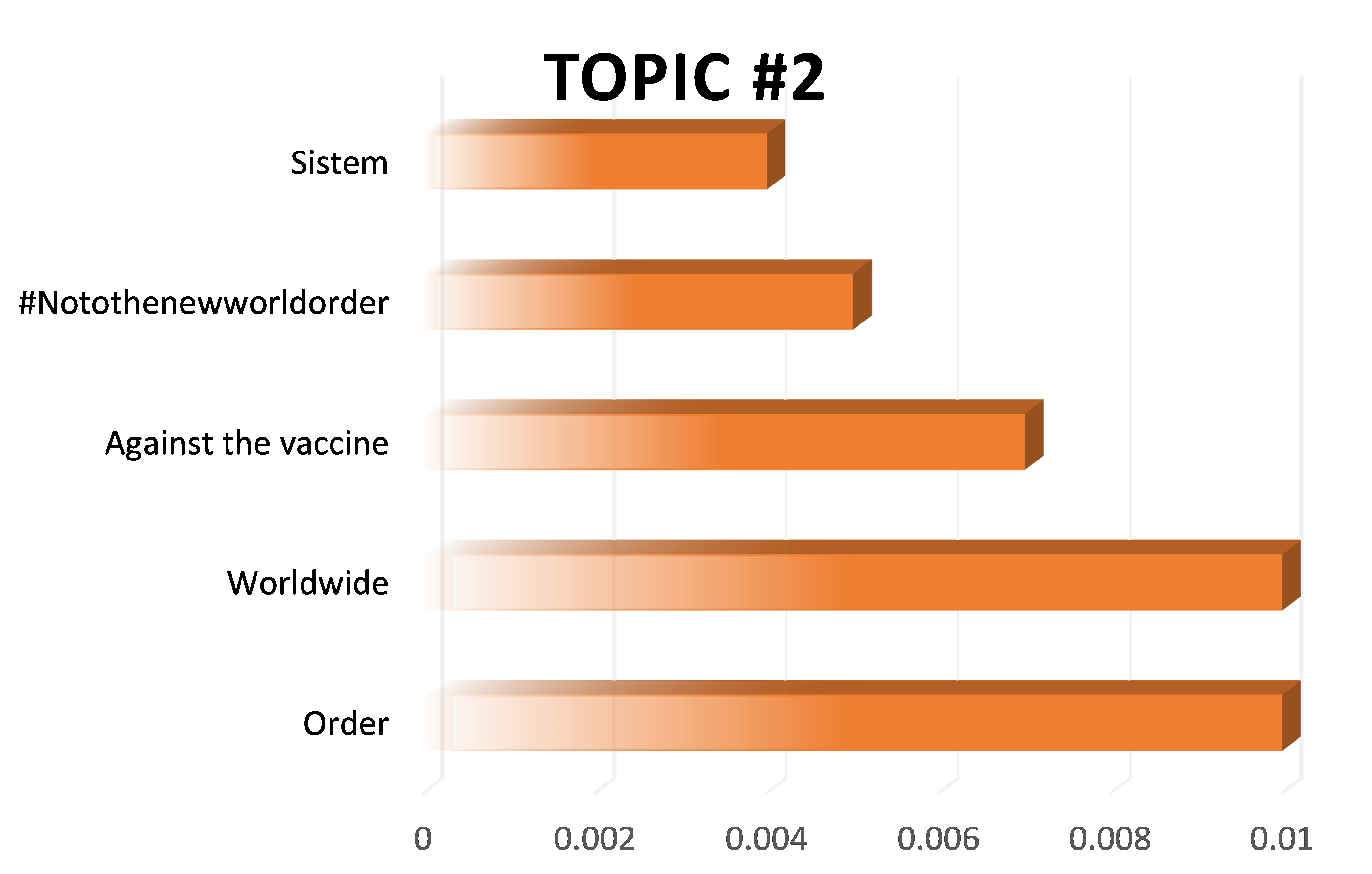

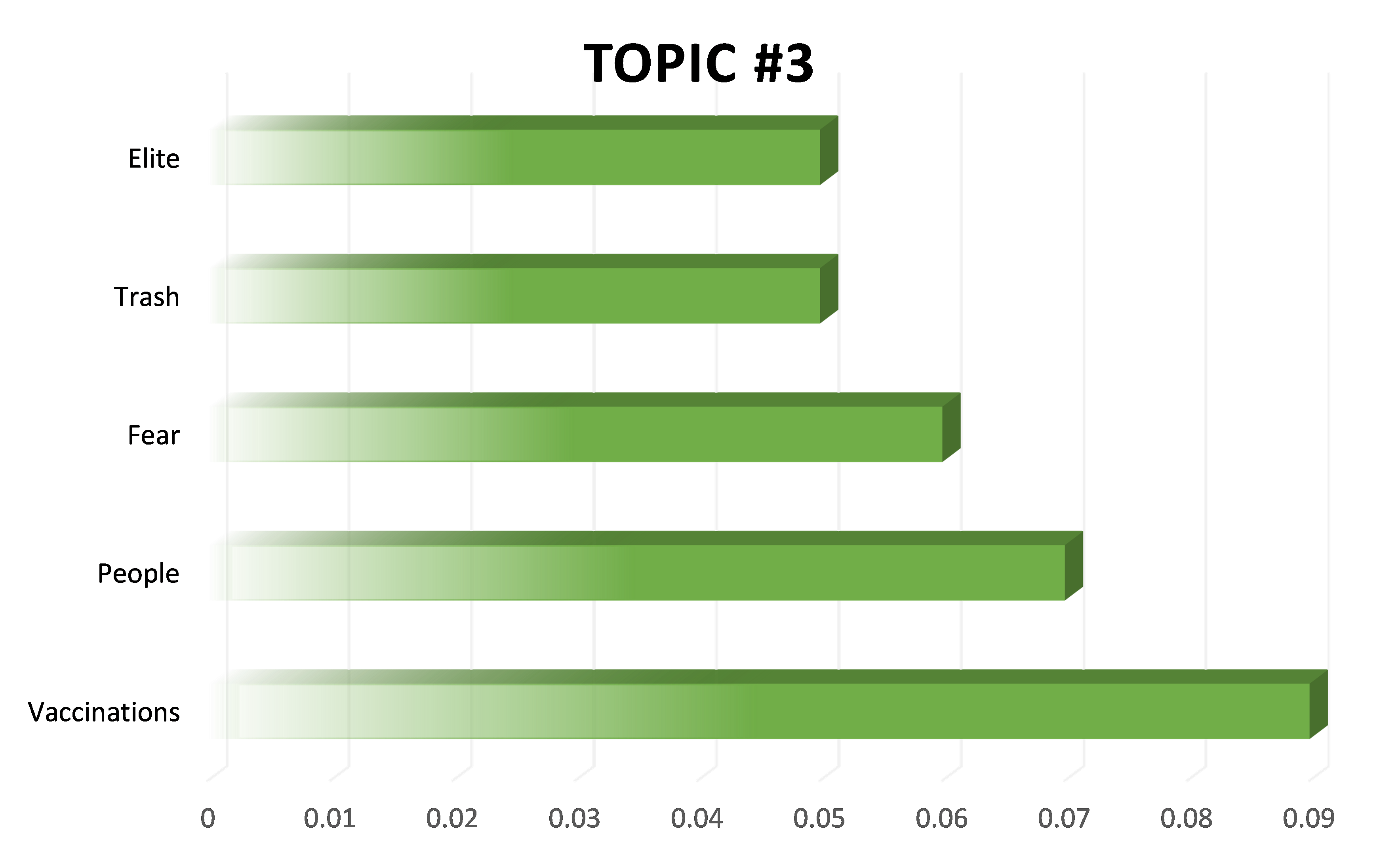

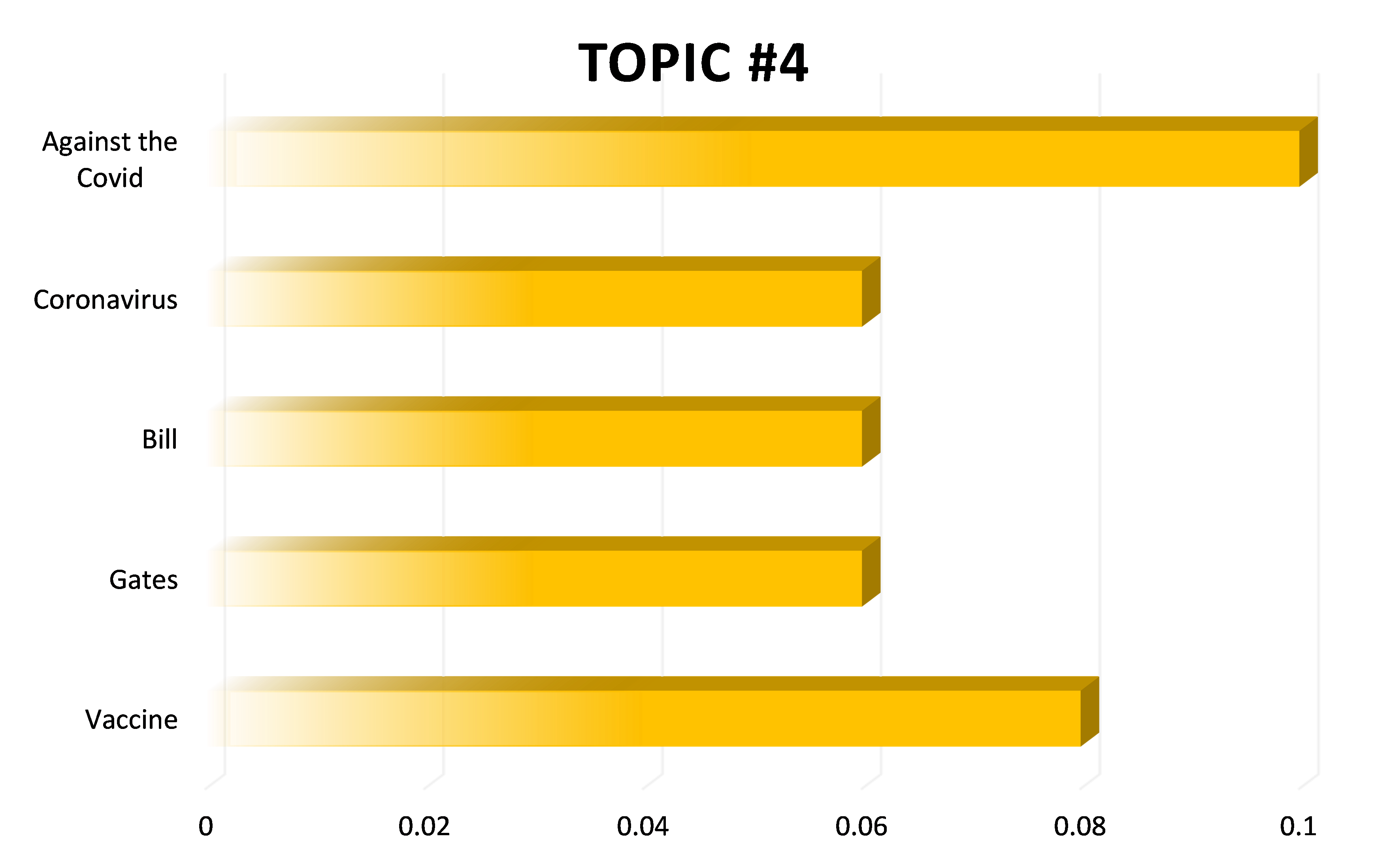

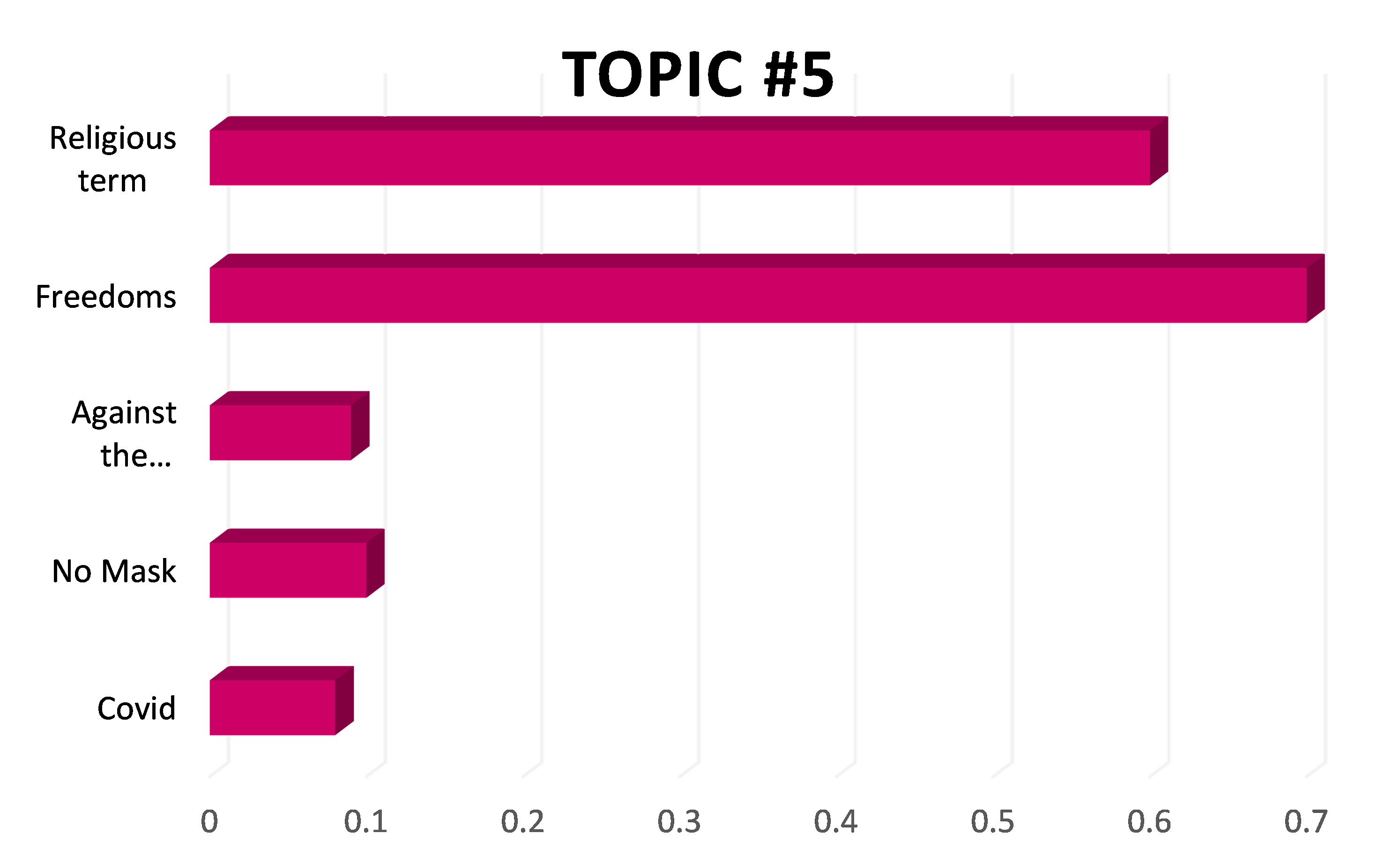

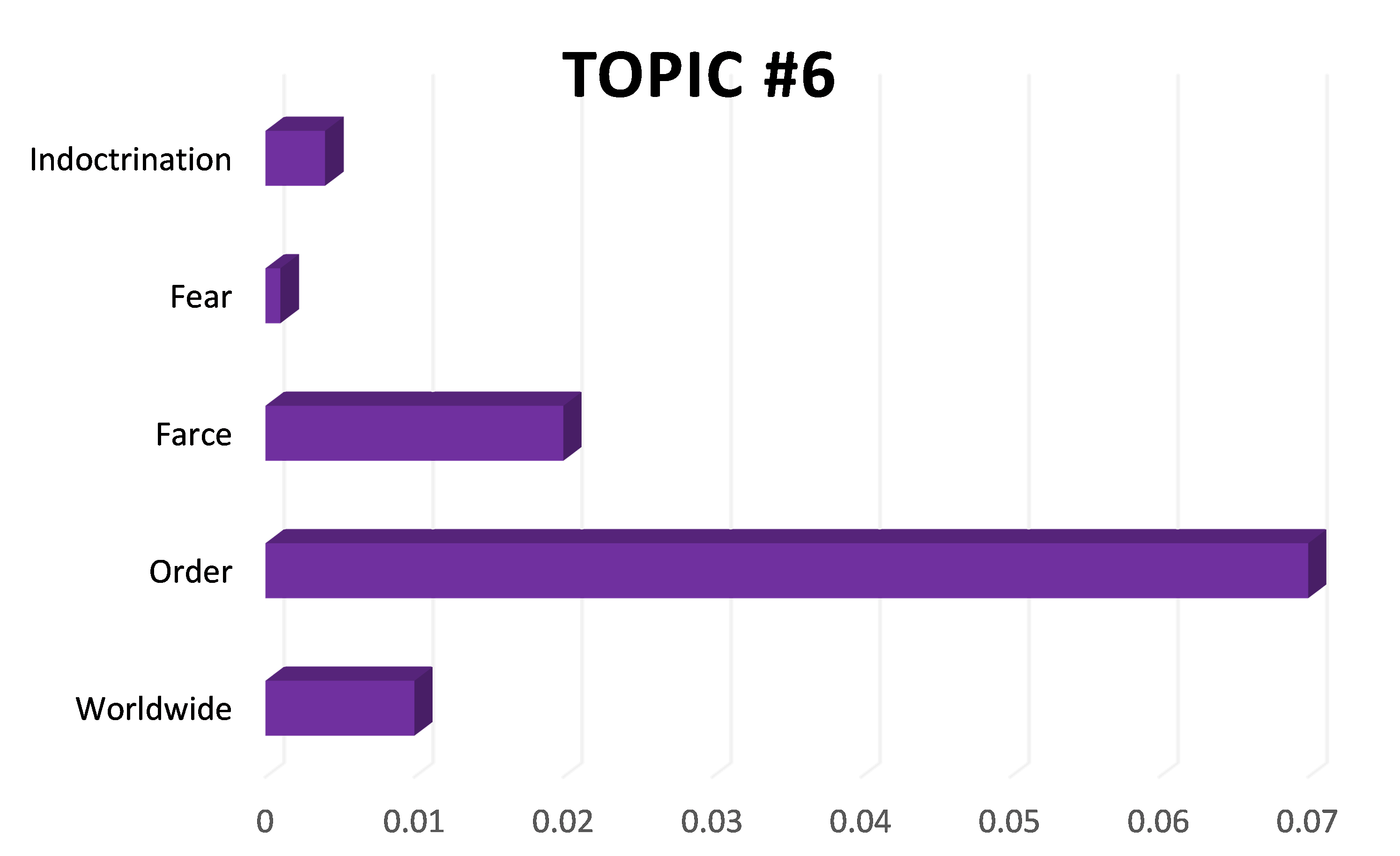

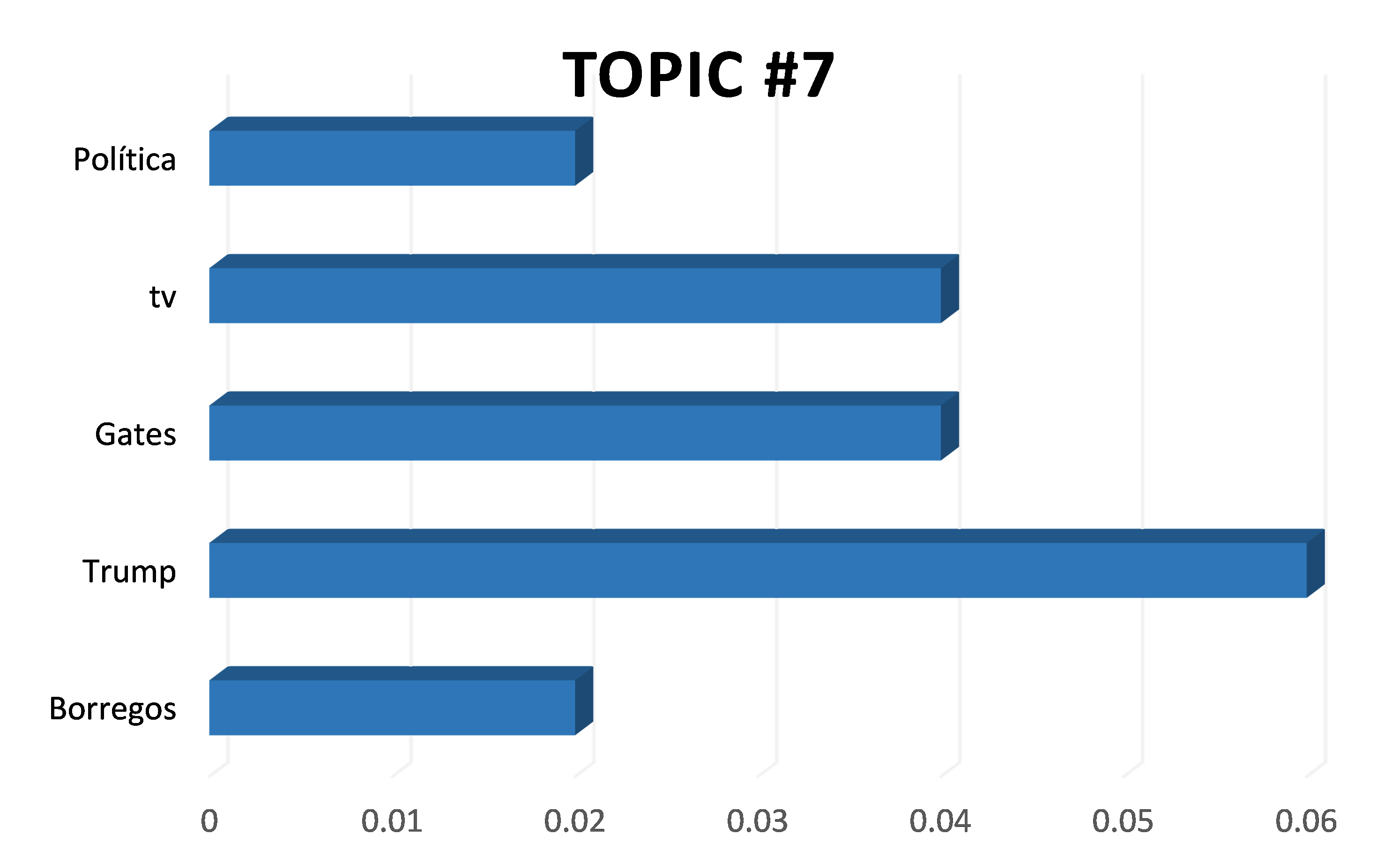

Based on the parameters of the topic model, the following graphs (Figure 4) show the five most relevant topics according to the weight (importance) of each group of topics. The contents of each of the seven topics found are shown below:

Within the first group of topics, we find vaccine, worldwide, 19, covid, world. For this group, reference is only made to issues related to covid and how it affected the world.

For the second group of topics, the most predominant weights are system, #nototheneworder, counter vaccine, world, and order, emphasising those who are against the system and thus are anti-vaccine.

Topic #3 involves words like elite, rubbish, fear, people, and vaccines. Mentioned that the elite do everything to create fear in people and thus apply the vaccine.

In topic #4, the terms range from being against the elite, as Bill Gates is linked to being in favour of vaccines, creating controversy about his actions, such as not being a vaccine participant nor empathetic to covid's health measures.

In topic #5, religious issues are grouped with the ideology of being against masks and demanding freedom.

Conversely, topics six and seven mention indoctrination related to fear, the demand for order, pointing out that the pandemic was a farce.

While topic 7 focuses again on the elite and politics. It was mentioned that people who listened to media indications were sheep (people who allowed themselves to be influenced).

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 4. Most relevant topics of each group

Discussion

The results show that the page's publication frequency was related to actual events. January and February 2021 have been the months with the highest number of posts, which coincides with the beginning of mass vaccination in much of the world. On the other hand, the flow of information reaching the page from Telegram groups shows that this social network functions as an echo chamber to spread denialist, antivaccine, and conspiracy content, as other studies have shown (Soler-Roca, 2022). This situation happens because of the low verification filters it employs, and Facebook needs an effective censorship mechanism. The fact that only a tiny part of the posts on a page like No to the New World Order had a falsehood alert shows that the filters on Facebook are insufficient.

Continuing with the sources of information, Russia Today appears as the most shared TV station. This is related to its constant criticism of Western powers (banks or multinationals), which are used to argue conspiracy ideas. The criticism of these powers and organizations clarifies that the site maintains an anti-system position. In addition, they promote taking sides against the supposed New World Order, sharing content about rebellions, and explicitly inciting them. Likewise, institutional measures such as using masks, vaccination, and mobility restrictions have been the most criticized on the page. This is a typical result in other studies (Soler-Roca, 2022).

None of the posts contradicted the page's antivaccine ideas, denialism, or the conspiracy theories they shared. However, it is possible that someone had posted in an opposite way, but the administrators removed it for going against the page's ideas. Such a situation demonstrates that the page is not a space for debate on these issues and that their information dissemination project is as indoctrinating as officialdom, which they criticize. This possible is given by confirmation bias, which makes them reject content that contradicts their beliefs. This disconfirmation bias causes subjects to reject information that challenges their prior beliefs, as confirmed by other studies on vaccination-related information (Savolainen, 2022). At the same time, they have a positive predisposition toward content that confirms and nurtures their beliefs (McIntyre, 2018). Therefore, it is more common on the page to disseminate information (sharing) than dialogue (commenting).

On ideology, some interesting data are found. For example, Donald Trump was the most praised public figure, sometimes presented as a hero fighting against China and the mysterious powers behind the pandemic. Studies have shown that populist leaders use conspiracy theories to reshape their image as fighters against hidden powers and thus gain followers (Mancosu et al., 2017). There were also overt attacks on LGBTQ+ collectives, feminism, and abortion rights. In addition, they shared nationalist content. Communism was listed as one of the main enemies to fight, and there was a religious foundation in the ideas shared on the page. All these elements are characteristic of conservative ideology. Other studies have shown a relationship between this ideology and antivaccine, denialist, and conspiracy ideas (Featherstone et al., 2019; Hornsey et al., 2020). In addition, conservative users stand out as spreaders of pandemic disinformation on social networks (Vosoughi et al., 2018).

The page criticizes more left-wing or left-leaning rulers (Pedro Sánchez, Xi Jinping, Andrés Manuel López Obrador) than right-wing ones. On the other hand, when it comes to praising rulers (Donald Trump, Ulf Kristersson, Vladimir Putin, or Andrés Manuel López Obrador), it does not show preferences for a political camp. This fact means that ideological affiliation is not as crucial as the correspondence between the ideas of the page and those of the rulers. It is not so important whether the ruler tends to the left or the right, but how critical he is about covid-19 situation or the New World Order. For example, Donald Trump was very critical of covid-19, to the point of spreading fake news (Pérez-Dasilva et al., 2020). Sweden (Kristersson) was among the few countries that did not follow World Health Organization recommendations and implemented very few measures to contain the virus (Pulido-Montes et al., 2021). Vladimir Putin has always been very critical of the West (Cabrera, 2020), and Andrés Manuel López Obrador used to refuse to wear a mask. All these actions are closely related to the ideas of the page.

No to the New World Order is a page with very little sense of humour. This contrasts with the circulation of humorous content, in hoaxes or fake news, where hoaxes are the fourth most shared type of hoaxes, which seems minor. However, in proportion, they are still more significant than here, as shown by other studies (Aguila Sánchez and Pereyra-Zamora, 2022). On the other hand, is used childhood as a persuasive resource to draw attention to the situation and raise awareness of the ‘harm done by vaccines’: infants are portrayed as victims.

The page also criticises verification agencies, whose objective is to corroborate and deny information. In contrast, the verification agencies are presented here as censorship mechanisms that do not allow alternative versions of the pandemic to flourish. As sympathizers of the alternative, on the page, they share several posts with critical ideas of Julian Assange against the media, which serve them to justify what they call the new world order. On the other hand, they advocate nutritional eating, exercising, and having fun instead of getting vaccinated to stay healthy. This advice promotes health care. However, it is questionable that it is presented in opposition to vaccination, not in conjunction.

One of the central contradictions of the discourse on the page is that, on the one hand, they assure that the virus does not exist, and, on the other hand, they recognize that it does exist but is not so harmful. This incongruity is common to other groups of denialists in social networks (Soler-Roca, 2022). Another contradiction is that Bill Gates is presented as a multimillionaire businessman who intends to do business during the pandemic. Moreover, at the same time, he is presented as a promoter of the end of capitalism for being subordinated to the global power of socialism.

The most shared publications are an example of the contents that they want to keep on the page's agenda. In turn, interactions (posting, sharing, reacting, and commenting) demonstrate the impact of those contents on followers. According to Reig Alamillo and Elizondo Romero (2018, p. 59), ‘emoticons are reactive acts summoned, and not required.’ They are given as a reaction to a post, and although they are expected, they may or may not occur. So, the likes a post receives reflect its acceptance among the page's followers. Likewise, the fact that one of the most liked posts is a reflection on his experience of staying healthy without considering the official recommendations shows that talking about personal experience, in this case of going against what is recommended, is a solid persuasive resource to attract followers.

Peretti-Watel et al. (2015, p. 3) note that casting doubt on vaccination is an old phenomenon that ‘is often attributed to ignorance, misinformation or irrationality.’ Moreover, conversely, ‘those who describe it as a new attitude, distinct from strong opposition to vaccination, also argue that it is positively related to vaccine literacy.’ Beyond both positions, what is clear is that information plays an essential role in forming one or the other ideas. Moreover, today, it is a phenomenon fuelled by misinformation circulating on social media (Latkin et al., 2021).

Conclusions

The study results allow us to conclude that pandemic denialist discourse is related to other ideas, such as antivaccine ideas and conspiracy theories. They are also related to conservative ideas, such as anti-LGBTQ+, anti-abortion, anti-feminist, anti-communist, or pro-Christian content. On the other hand, even though Facebook has a censorship system for disinformation, it does not work, besides Facebook still a valuable platform for sharing this type of content. False, decontextualized, or even hate speeches circulate in this social network.

As shown in the results, two-thirds of the contents were generated from the page, and one-third constituted posts from other sites (mainly Telegram). This means the community is proactive in what it shares and spends time generating conservative, anti-institutional, and conspiracy speeches in various formats (mainly videos and images) that interact with other platforms.

The data show that page's content was oriented against measures taken by the governments to contain the pandemic, particularly against restrictions on mobility, vaccinations, and the mandatory use of masks. There was also criticism directed towards people who followed the institutional measures, who were referred to with derogatory adjectives. This criticism of those who think otherwise goes in both directions. Another clear orientation of the page was against the informative handling of the pandemic. Likewise, the page has a global perspective because of institutions and subjects that praises and criticizes, even though it is administered from Mexico.

The conspiracy ideas expressed in the publications pointed to unspecific entities such as elites or Agenda 2030. These conspiracy ideas identify the purpose of the pandemic as the establishment of a New World Order involving depopulation and genocide, hence the noun plan-demia. The posts hold conservative ideas against not only vaccines but also women's rights (especially abortion) and LGBTQ+ groups. They promote parental control in families, manifest some form of religiosity, and favour leaders with authoritarian styles, such as Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump.

It is essential to mention that although the topics were not assimilated to the seven themes raised in the research, most are close to the hypothesis. In other words, the relationship between the themes can be observed, which shows that users maintain conspiratorial attitudes and try to rebel against the system, as they are not satisfied with the measures demanded by the supreme powers.

Based on the published content, it can be observed that No to the New World Order serves as a platform for criticizing pandemic management across all fronts. However, this space does not accommodate divergent opinions, criteria, or perspectives, nor does it offer criticism or questioning of the accuracy of shared content. These conditions foster misinformation and polarization on the issue.

Acknowledgements

The study on which the paper was based was supported by the National Council of Humanities, Sciences and Technology of Mexico, grant number 784757.

About the authors

Julio C. Aguila Sánchez is a postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Anthropological Sciences of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, Mexico. He researches on health communication during the pandemic. Email: julio.aguila@virtual.uady.mx

Carmen Castillo Rocha is a professor and researcher at the Faculty of Anthropological Sciences of the Autonomous University of Yucatan, Mexico. She researches communication for social change. Email: ccastillo@correo.uady.mx

Ángel R. Vargas Valencia is a doctor and director of the University Centre for Statistical Analysis and Public Opinion, at the University of Colima. He is a researcher in social sciences and statistics. He is a professor at the Faculty of Nursing. Email: avargas22@ucol.mx

References

Aguila Sánchez, J. C., & Pereyra-Zamora, P. (2022). Infodemics in Mexico: a look at the Animal Político and Verificado fact-checking plaforms. Health Education Journal, 81(8), 982-992. https://doi.org/10.1177/00178969221130462.

Barbaros, M. C. (2022). For better or for worse? An integrative perspective of message framing moderators’ effects on vaccination sustainable health behavior change. Sustainability, 14(23), 15793. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315793

Bennett, W.L., & Livingston, S. 2018. The disinformation order: Disruptive communication and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231 18760317

Bertin, P., Nera, K., & Delouvée, S. (2020). Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: a conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 565128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128

Boxell, L., Gentzkow, M., & & J Shapiro (2017). Is the internet causing political polarization? Evidence from demographics. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23258

Boyd D. (2010). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Papacharissi Z. (Ed.), A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites (pp. 39-58). New York: Routledge.

Brotherton, R. (2013). Towards a definition of ‘conspiracy theory’. Psychology Postgraduate Affairs Group Quarterly, (88), 9-14. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpspag.2013.1.88.9

Cabrera, J. M. (2020). Las luces y sombras de Rusia en la pandemia: entre la ayuda sanitaria y las fake news. [Russia's light and shadows in the pandemic: between health aid and fake news]. In M.V. Alvarez, & M.R., Novello (Eds.), La Federación Rusa y el covid-19 ¿Oportunidad o crisis? (pp. 22-29). Universidad Nacional de Rosario. https://bit.ly/4cqUvDk (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/4c0CnAn)

Davis, A. (2019). Political communication: A new introduction for crisis times. Polity. https://bit.ly/3VxVjiG (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://www.politybooks.com)

Douglas, K. M. (2021). COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 270-275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220982068

Dubé, È, Ward, J. K., Verger, P., & Macdonald, N.E. (2021). Vaccine hesitancy, acceptance, and anti-vaccination: trends and future prospects for public health. Annual Reviews of Public Health, 42(1), 175-191. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102240

Featherstone, J. D., Bell, R. A., & Ruiz, J. B. (2019). Relationship of people’s sources of health information and political ideology with acceptance of conspiratorial beliefs about vaccines. Vaccine, 37(23), 2993-2997. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.063

García, F., Lamirán, J. M., & Broseta, B. (2024). Más allá del número de seguidores: : Medición de la resonancia en redes sociales basada en interacciones directas [Beyond the number of followers: Measuring social media resonance based on direct interactions]. Visual Review, 16(3), 239-250. https://doi.org/10.62161/revvisual.v16.5260

Gargiulo, F., Cafiero, F., Guille-Escuret, P., Seror, V., & Ward, J.K. (2015). Asymmetric participation of defenders and critics of vaccines to debates on French-speaking Twitter. Scientific Report, 10, 6599. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62880-5

Hornsey, M. J., Finlayson, M., Chatwood, G., & Begeny, C.T. (2020). Donald Trump and vaccination: The effect of political identity, conspiracist ideation and presidential tweets on vaccine hesitancy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 88, 103947. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103947

Innerarity, D., & Colomina, C. (2020). Introducción: desinformación y poder, la crisis de los intermediarios. [Introduction: disinformation and power, the intermediaries crisis]. CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, (124), 7-10. https://doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2020.124.1.7

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480-498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480

Latkin, C. A., Dayton, L., Yi, G., Colon, B., & Kong, X. (2021). Mask usage, social distancing, racial, and gender correlates of COVID-19 vaccine intentions among adults in the US. PloS one, 16(2), e0246970. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246970

Lewandowsky, S., Gignac, G. E., & Oberauer, K. (2013). The role of conspiracist ideation and worldviews in predicting rejection of science. PloS one, 8(10), e75637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0134773

Mancosu, M., Vassallo, S., & Vezzoni, C. (2017). Believing in conspiracy theories: evidence from an exploratory analysis of Italian survey data. South European Society & Politics, 22(3), 327-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2017.1359894

McIntyre, L. (2018). Post-truth. The MIT Press.

Peretti-Watel, P., Larson, H. J., Ward, J. K., Schulz, W. S., & Verger, P. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: clarifying a theoretical framework for an ambiguous notion. PLoS Currents, 25(7), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1371/currents.outbreaks.6844c80ff9f5b273f34c91f71b7fc289

Pérez-Dasilva, Jesús-Ángel; Meso-Ayerdi, Koldobika; Mendiguren-Galdospín, Terese (2020). Fake news and coronavirus: Detecting key players and trends through analysis of Twitter conversations. El profesional de la información, 29(3), e290308. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.08

Prior, M. (2007). Post-broadcast democracy: How Media choice increases inequality in political involvement and polarizes elections. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139878425

Prior, M. (2013). Media and political polarization. Annual Review of Political Science, 16, 101-127. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135242

Pulido-Montes, C., Francia, G., & Ancheta-Arrabal, A. (2021). Biopolíticas de cierre de centros educativos desde una perspectiva de género: los casos de España y Suecia. [Biopolitics of educative centers closing from gender equality perspective: the cases of Spain and Sweden]. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, 38(1), 17-43. https://doi.org/10.5944/reec.38.2021.29021

Reese, S., Rutigliano, L., Hyun, K., & Jeong, J. (2007). Mapping the blogosphere: Professional and citizen-based media in the global news arena. Journalism, 8(3), 235-261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884907076459

Reig Alamillo, A., & Elizondo Romero, A. (2018). Un análisis de la reacción me gusta en Facebook desde los estudios de la interacción. [An analysis of the Facebook like reaction from interaction studies]. Estudios de Lingüística Aplicada, 36(67), 45-75. https://doi.org/10.22201/enallt.01852647p.2018.67.722

Salmeron Henríquez, J. A. (2017). Oposición a las vacunas en Chile. Análisis de un caso reciente. [Opposition to vaccines in Chile: analysis of a recent case]. Revista chilena de derecho, 44(2), 563-574. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34372017000200563

Robles, J., Guevara, J., Casas-Mas, B., & Gómez, D. (2022). When negativity is the fuel. Bots and Political Polarization in the COVID-19 debate. Comunicar, 71, 63-75. https://doi.org/10.3916/C71-2022-05

Román-San-Miguel, A., Sánchez-Gey-Valenzuela, N., & Elías-Zambrano, R. (2020). The fake news during the COVID-19 State of Alarm. Analysis from the political point of view in the Spanish press. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, (78), 359–391. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1481

Savolainen, R. (2022). What drives people to prefer health-related misinformation? The viewpoint of motivated reasoning. Information Research, 27(2), 927.https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper927

Smith, N., & Graham, T. (2019). Mapping the anti-vaccination movement on Facebook. Information, Communication & Society, 22(9), 1310-1327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1418406

Soler-Roca, C. (2022). Teorías de la conspiración, negacionismo del COVID-19 y movimientos en contra de las medidas para la contención de la pandemia. [Conspiracy theories, COVID-19 denialism and movements against measures to contain the pandemic]. Debats. Revista de cultura, poder y sociedad, 136(1), 118-131. https://revistadebats.net/article/view/4525/4872 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://revistadebats.net/article/view/4525)

Starbird, K. (2021, February) Online rumors, misinformation and disinformation: The perfect storm of covid-19 and Election2020. In Enigma 2021. USENIX Association. https://www.usenix.org/conference/enigma2021/presentation/starbird (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://www.usenix.org/conference/enigma2021)

Tajfel, H. (1984). Grupos humanos y categorías sociales. [Human groups and social categories]. Barcelona. Herder.

Valera-Orgaz, L. (2017). Comparing the democratic value of Facebook discussions across the profiles of Spanish political candidates during the 2011 General Election. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 75(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2017.75.1.15.119

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146-1151. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aap9559

Ward, J. K., Alleaume, C., & Peretti-Watel, P. (2020). The French public's attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 1-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414

Ward, J. K., Peretti-Watel, P., Larson, H. J., Raude, J., & Verger, P. (2015). Vaccine-criticism on the internet: new insights based on French-speaking websites. Vaccine, 33(8), 1063-1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.064

World Health Organization. (2022). Infodemic. https://bit.ly/3ze8NX0 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://www.who.int)