Information Research

Special Issue: Proceedings of the 15th ISIC - The Information Behaviour Conference, Aalborg, Denmark, August 26-29, 2024

Information seeking behaviour in music conductors’ repertoire selection

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir292827

Abstract

Introduction. Music repertoire selection is a process driven by music conductors. They focus on scoring, ensemble composition, acquisition methods (i.e., acquiring the music). Information needs and seeking are core to repertoire selection and conductors’ tasks/roles. It cannot be considered in isolation; other conductor responsibilities, past experiences, and external factors (e.g., finances) influence the process and information seeking. We report findings from an exploratory study conducted in 2023 with 37 conductors.

Method. Brief literature review, triangulated with findings from a mixed-method study. A semi-structured questionnaire collected quantitative data from 37 conductors and individual online interviews collected qualitative data from two conductors.

Analysis. Quantitative data revealed typical tasks requiring information, issues to consider in repertoire selection (e.g., text, ensemble capabilities), internet usage and other information seeking activities and sources. Qualitative data elaborated on factors influencing repertoire selection and information seeking e.g., repertoire inspiration and financial factors.

Results & discussion. Three core themes influencing information seeking are discussed: process of repertoire selection, user (individual conductor) characteristics, external factors. The repertoire selection (process) is mapped against information seeking behaviour (activities, sources), user characteristics and external factors.

Conclusion. Music repertoire selection’s interdependence with other tasks of music conductors, the importance of individuality and inevitable external factors, influence information seeking.

Introduction

The information seeking behaviour of music conductors (further referred to as conductors) is influenced by various aspects, including (but not limited to) the availability of musicians/ensemble, available timeline, occasion, venue, sheet music availability, and whether the music can be performed by their ensemble (Brown, 2015, p. 78). A conductor is defined by Brown (2015, p. 78) as an individual who is ‘a conduit for the music’, transferring energy to their ensemble and the audience to allow for the meaning of the music to be conveyed. There are various types of conductors, such as conductors for ‘marching band, orchestra, dance band, choral group, or a small string ensemble’ (Lüsted, 2011, p. 35). This paper will only focus on two types of conductors, choral and orchestral.

Information behaviour and information seeking behaviour research within the field of music is quite limited; there is, however, a growing interest in the field, e.g., recent publications such as Bronstein and Lidor (2021), Lugović (2022), Munro et al. (2022), and Nwokenna et al. (2022). At the time of writing, publications connecting music repertoire selection (further referred to as repertoire) with information behaviour or information seeking behaviour did not emphasise all aspects of repertoire selection. Schrock (2009, p. iii) defines repertoire as a collection of pieces that consist of a small amount of the music available and accessible globally. When selecting repertoire for an ensemble, conductors need to develop a balanced programme consisting of pieces on the ensemble’s level, a piece below their level, and a more difficult piece to challenge the ensemble (Brinson, 1996, p. 75; Hopkins, 2013, p. 74).

The need for a better understanding of information seeking behaviour, part of the comprehensive, umbrella concept of information behaviour (Wilson, 1999), led to an exploratory study that was conducted in 2023 focusing on the process of repertoire selection, and specifically the tasks and role of the conductor and how to map the activities of information seeking, use of information sources, conductor roles and tasks, and factors influencing information seeking behaviour. The value of such understanding would allow conductors in training to be better advised on details pertaining to the process, including aspects to consider in relation to information seeking activities and the use of information source. The intention is for the findings and insights from the exploratory study to guide further data collection on understudied aspects related to music information seeking and behaviour.

The 2023 study was guided by the question: Which aspects and information seeking strategies are employed by conductors when selecting repertoire for their ensembles? The intention of this paper is to address only one component of the larger study, namely:

How can the details of the repertoire selection process be mapped to information seeking activities, information sources, and factors influencing choices?

Conductors work with ensembles. An ensemble consists of singers and/or instrumentalists who are, mostly, conducted (smaller ensembles do not always have a designated conductor). A choral ensemble can consist of sopranos, altos, tenors, and basses who can sing in unison (same melody) or voice groups can be divided, also referred to as divisi (Brown, 2015; Shrock, 2009; Stamer, 2002). An orchestra consists of instrumentalists that are divided into four main groups, namely strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion (Brown, 2015; Burdukova, 2010). Ensemble sizes can vary between a few musicians to thousands of musicians participating in mass events (Titze and Maxfield, 2017). An ensemble does not need to consist of all voice groups or instrumentations (Brown, 2015). For example, a female choir would usually only consist of the voice groups soprano and alto, and a marching band might consist of only wind and percussion instruments. The conductor selects the repertoire and takes care of other tasks such as scoring, ensemble composition, acquisition methods, communicating with administration, gathering sponsors, to mention a few. Repertoire selection is considered a conductor’s most important and challenging task before they can begin rehearsing and performing a selected repertoire with their ensemble (Apfelstadt, 2000; Rotjan, 2021). A conductor’s role needs to encompass and encourage their ensemble’s growth and learning, through the selection of relevant repertoire (Nielsen et al., 2023).

This paper will cover the following: clarification of concepts (information seeking behaviour, music conductor, repertoire selection), background focusing on the context of information behaviour and two related models, methods, findings, and discussion, and lastly, the details of the repertoire selection process mapped to information seeking activities, information sources and factors influencing choices and information seeking behaviour.

Clarification of concepts

The clarification of the three concepts will allow for the understanding of the paper’s contents. The concepts clarified are information seeking behaviour, music conductor and repertoire selection.

Information seeking behaviour

Information seeking is the process to seek for information relevant to accomplishing a task or to resolve an information need and to broaden an individual’s knowledge base (Case and Given, 2016, p. 91; Ikoja-Odongo and Mostert, 2006, p. 148; Tubachi, 2018, p. 2; Wilson, 2000, p. 49). The process of information seeking consists of an information need which triggers information seeking and assists in the seeking, choice of information sources, evaluation, selection, and use of the information relevant to the information need (Case and Given, 2016, p. 92; Ikoja-Odongo and Mostert, 2006, p. 149; Tubachi, 2018, p. 2). Information seeking is an information activity that falls under the umbrella term of information behaviour proposed by Wilson and other leading researchers and that includes the recognition of information needs, information searching, information encountering, information avoidance, information sharing and information use (Fourie and Julien, 2014).

Music conductor

Music conductors are the leaders and central figures of their ensembles communicating through nonverbal gestures representing tempo, dynamics, and emotion in rehearsals and performances (Brown, 2015, p. 78; Matthews and Kitsantos, 2007, p. 6; Yarbough, 1975, p. 134). A conductor conveys the emotion of a piece to their ensemble and to the audience; this allows for their own interpretations and perspectives to be introduced to their constantly evolving audience (Núñez, 2012, p. 210).

Repertoire selection

Repertoire selection is considered ‘the single most important task that music [conductors] face before entering the classroom or rehearsal room’ (Apfelstadt, 2000, p. 19; Atchison, 2015, p. 16). Repertoire selection consists of multiple considerations and principles, such as selecting good quality, teachable, and context appropriate music that can be accomplished by their ensemble (Apfelstadt, 2000, p. 19-21). A well-structured repertoire cannot be accomplished by selecting random pieces but should consist of a balance of easy and difficult pieces (Atchison, 2015, p. 16; Hopkins, 2013, p. 71).

Background

Information seeking behaviour research allows for a deeper insight of an information user’s job, profession, context and how they deal with challenges, decisions, tasks and responsibilities on professional and personal levels. This has been researched extensively e.g., with regard to healthcare professionals, lawyers and researchers (Agarwal, 2017; Meyer, 2018; Wilson, 2022). By understanding a user’s context and surroundings, the numerous interactions and in particular information interactions constantly taking place can be understood and interpreted (human-human, human-computer) (Agarwal, 2017; Given et al., 2023; Savolainen, 2012). Various models of information behaviour and information seeking have been developed to explain findings and to direct research (Given et al., 2023; Wilson, 2022). Rousi et al. (2016) argued that the context of music encompasses ‘different music information facets’, such as technological models of music as the first mode of symbolic representations and ideological models of music as the second mode of symbolic representations. Technological models focus on the study of music harmonies, counterpoints, and the composition of a piece of music. The ideological models consist of abstract methods of information representation, emotions, text, nuance, etc. Repertoire selection by a conductor consists of the technological and ideological models being represented throughout each piece selected while considering their ensemble throughout.

To study and understand the information seeking behaviour of conductors, note must be taken of earlier related work and models of music, in particular information behaviour and information seeking behaviour that can guide research and portray the importance of the context in which conductors operate.

In the following subsections we discuss information behaviour models suitable for the research question, a brief review of relevant literature and the importance of context when studying information behaviour and how that applies to music conductors. Findings from related studies in music and information behaviour are acknowledged. The focus is on the conductor’s repertoire selection process.

Relevant information behaviour/seeking models

Many information behaviour and information seeking models have been discussed in the literature e.g., in the books of Case and Given (2016), Wilson (2022) and Given et al. (2023). Some of these might be used for studies in the context of music. Models and discussions of models that stood out are Chandler’s (2019) discussion of Hektor’s (2001) information behaviour model and how it could connect to conductors, Wilson’s (1981) general model of information behaviour, Webster’s model of creative thinking as discussed by Lavranos et al. (2015) and Kostagiolas et al.'s (2017) discussion of how information seeking behaviour within music and the musicians’ personality can motivate musical creativity. The literature also reports on Kuhlthau’s (2004) information search process model in comparison to Tarasti’s (1994) theory of music semantics model as discussed by Rousi et al., (2016) in their study of the typology of music information. Laplante’s (2008) study about young adults’ music information seeking behaviour in everyday life notes various well-known information behaviour models e.g., by Bates (1989), Dervin (1992), Ellis (1989), Kuhlthau (1991), and Wilson (1981), to mention a few. Byström and Järvelin (1995) developed a holistic general model that focused on task complexity and information seeking and use by focusing on individual tasks and not a collective of tasks. Their model showcases that the complexity of a task impacts the type of information and channels used to accomplish the task (Byström and Järvelin, 1995).

For the exploratory study focusing on the process of repertoire selection (i.e., a professional activity related to a role and tasks) and the activities influencing a (creative) professional (i.e., a conductor), we considered two models in more detail. These are the Wilson (1981) general information behaviour model and the Leckie et al. (1996) (professional information seeking) model. Each model is briefly discussed before explaining why they were chosen and applied in the study. We decided to focus on the context in which the process of repertoire selection is conducted and influencing factors and not on the detail of task-oriented information seeking as portrayed in the very useful work of Byström and Järvelin (1995), Vakkari (2008), and Savolainen (2012).

Wilson’s (1981) model consists of three components which influence an individual’s information needs: person, role, and environment (Wilson, 1981, p. 8). He added that psychologists identified three experiences that impact on information seeking, namely physiological (e.g., food, shelter, security), affective (e.g., attention, attainment, reassurance), and cognitive (e.g., skills, learning, previous experiences) (Wilson, 1981, p. 7). Each component is also influenced by personal, interpersonal, and environmental barriers and challenges that impacts on the ability to seek and find information. Thus, influencing information seeking behaviour (Wilson, 1981, p. 8). This model held value for a study with conductors and the repertoire selection process as explained in the Section Clarification of Concepts; a conductor’s repertoire selection process is impacted by the person and their environment (Rotjan, 2021). Our assumption was that the person and environment (i.e., context) might also influence information seeking behaviour. For purpose of this paper, we will focus on repertoire selection as a process that could also cover tasks like rehearsing and performing the repertoire, selection of ensemble members and understanding their audience (Fena, 2021; Jansson et al., 2021).

Leckie et al.’s (1996) (information seeking of professionals) model brought the importance of researching professionals to the forefront. The model was developed based on a study with engineers, health professionals and lawyers, but can be implemented as a model utilised across professions (Leckie et al., 1996, p. 180). In their study each professional’s work consists of multiple roles such as service provider, administrator/manager, researcher, educator and student (Leckie et al., 1996). Each role consists of its own tasks; the characteristics of information needs will differ (Leckie et al., 1996). The sources selected and awareness of information impact the outcome of the information sought. The model also allows for feedback to be provided e.g., to the source, awareness, and/or information sought out (Leckie et al., 1996). Although the Leckie et al. (1996) model is dated and has been criticised, it still holds value as shown by Given et al. (2023, p. 150, 155) and Wilson (2022, p. 69). The model has assisted in the development of more recent models, e.g. the Robson and Robinson model (2013) and the Freund model (2015).

Both models discussed have a focus on the individual’s role; the Leckie et al. (1996) model focuses on the individual’s professional role, where Wilson’s (1981) model incorporates an individual’s work and personal roles (thus not restricted to just work roles but extending to personal roles). Both models do not restrict individuals to one type/aspect of a role. The models do not explicitly focus on tasks related to a role or the processes fulfilled by someone in that role. Wilson’s (1981) model raises awareness for an individual’s affective needs and that barriers might be experienced throughout information seeking and selection. The Leckie et al. (1996) model adds value by emphasising the need for feedback to be provided when the desired outcome is not achieved, allowing the individual the opportunity to re-evaluate their information needs. A combination of the Wilson (1981) and Leckie et al. (1996) models guided the collection of data for the empirical component discussed in the section, Method. The questionnaire and interview schedule used for the exploratory study is included in Appendix I (Questionnaire) (asking about type of conductor, years of experience, formal music training, number of ensembles, the categorisation of components [music scoring and ensemble aspects] and methods to acquire music [internet, conversions, colleagues, etc.] utilised, and possible barriers experienced throughout repertoire selection [finances, timing, sheet music availability, etc.]), and Appendix II (Interview schedule) (asking about what inspires them, important aspects in the repertoire selection process, challenges experienced, experiences that shaped how they select the repertoire and advice to others).

Brief review of related studies

Although information behaviour and information seeking behaviour research within the field of music is quite limited, there is an increase in interest as noted in the Introduction. Due to the rapid advances in technology, musicians are not restricted when searching for sheet music (Hunter, 2006; Kostagiolas et al., 2015; Laplante, 2008). Utilising audio, written, and notated forms of music, musicians are introduced to old and new music, allowing for the constant evolution of their information seeking interest and behaviour (Hunter, 2006; Kostagiolas, et al., 2015; Rousi et al., 2016). The creativity portrayed by musicians contributes to the creativity established through music composition, performance, improvisation, and listening (Kostagiolas et al., 2017; Laplante, 2008). A conductor needs to be musically inclined and have good relationship building skills to be able to convey the meaning of the music (Brinson, 1996; Kostagiolas et al., 2017). Collins (1999) discusses four philosophies (naturalism, idealism, realism, pragmatism) that a conductor could portray. Each philosophy considers the conductor’s role as a leader, teacher, and fellow musician.

The identification of the correct repertoire by conductors is considered the most challenging and time-consuming part of a conductor’s job (Brown, 2015; Moore, 2021). Textbooks published by Brinson (1996) and Phillips (2004) identified various scoring and ensemble components that conductors need to consider when selecting repertoire. Chandler (2019), who focused on the information seeking behaviour of conductors, highlights the need for the conductor to be able to interpret sheet music and convey their interpretation to their ensemble. The study concludes that the role of a conductor is to not just select repertoire but to consider their ensemble and the long-term maintenance and standard the selected repertoire could represent (Chandler, 2019). A conductor does not only select and gather sheet music, but is also involved in the selection of musicians, solely responsible for interpreting and conveying the music to the musicians, leads rehearsals, and conducts the selected music in a performance/s. This showcases a conductor’s job description, highlighting that it is more than most expect (Fena, 2021; Jansson et al., 2021), moving beyond repertoire selecting and conducting.

Hedden and Allen (2019, p. 5) consider repertoire selection as ‘cumbersome, one that requires analysis of the music components, considerations for the performance venues, and time and effort to teach’. ‘The quality of a musical performance is inexplicably connected to the repertoire being performed’ (Hopkins, 2013, p. 74) and the selected repertoire determines the aesthetics of the ensemble. The selection of music is not limited to concert attendance, conference participation, or acquisition of sheet music and CDs (Chen, 2018). Conductors make use of the Internet, social media, online streaming platforms and by contacting composers directly rather than purchasing through a publisher (Chen, 2018). Chandler (2019) reports on a study with three interviewees that focused mainly on how they acquire sheet music. The study did not address information seeking and other components such as the scoring, ensemble and repertoire inspirations, and the possible external factors experienced throughout the repertoire selection process. The research conveyed in this paper expanded on the research conducted by Chandler (2019), hoping to convey the importance of the overall repertoire selection process (not just individual tasks that are part of the process; these might be studied at a later stage), the conductor’s influence on the process, the external factors experienced and how these relate to information seeking. Since there is little else known about the information seeking behaviour of conductors, our exploratory study seemed a timely opportunity to pave the way to future in-depth studies and issues to explore (cc Conclusion).

Importance of context in information behaviour research and relevance to music conductors

Researchers have identified different contexts within information behaviour research. Information behaviour research brings awareness to the concept of context while considering how an individual’s surroundings, psychology and social interactions may affect their information behaviour (Agarwal, 2017, p. 2). Information seeking behaviour research allows for a deeper insight to be established regarding the information user’s job, profession, and how they deal with challenges, on professional and personal levels; which has been researched extensively (Agarwal, 2017; Meyer, 2016, 2018; Wilson, 2022). Users’ numerous information interactions (human-human, human-computer) constantly take place and must be understood and interpreted in the context in which such interactions happen (Agarwal, 2017; Given et al., 2023; Savolainen, 2012). That includes information seeking as well as professional roles such as repertoire selection and the tasks associated with that role. This section focuses on the various contexts found in information behaviour research and connecting it to a conductor’s role with specific reference to the repertoire selection process.

Four main contexts (environment, personal, social, activities) were identified from discussions of information behaviour contexts by Savolainen (2012), Agarwal (2017), Meyer (2016, 2018) and Wilson (2022). We admit that there are many others, but for the purposes of our study, these seemed sufficient as points of departure. From these sources the following stood out:

Environmental contexts (including situations, settings)

Personal contexts (including user demographics, mindsets)

Social context (including interaction with others, networking)

Activities context

Environmental context

The environmental context does not just consist of an information user’s physical surroundings but also their virtual surroundings (Agarwal, 2017; Meyer, 2018; Savolainen, 2012). An individual’s physical and virtual surroundings used to be separate, however, due to the advancements and use of technology, the line between the physical and virtual have started to blur (Agarwal, 2017; Savolainen, 2012; Wilson, 2022). From the work of Hedden and Allen (2019), Hopkins (2013) and Chen (2018) it is evident that the environmental contexts for music conductors include the venues where performances take place and aesthetics. A conductor’s relationship with their ensemble also plays a pivotal role in understanding their environment, e.g., the ensemble’s community (Rotjan, 2021). A conductor’s environment consists of their work environment (e.g., geographic location, funding [institutional, organisational]) and social environment (possible ensemble members, colleagues, participation at conferences and symposia, etc.) (Biasutti, 2012; Rotjan, 2021). The social environment might also be considered as a social sphere.

Personal context

The personal context within information behaviour mainly focuses on an individual’s cognitive, affective, and sensorimotor structures, allowing for the accomplishment of information needs (Meyer, 2018, p. 32). This context focuses on an individual’s mental capabilities to be able to fulfil information needs within their environment, role, decision-making and everyday life (Meyer, 2018, p. 32). It also includes demographic characteristics such as age and gender. For musicians such as conductors the personal context could include creative abilities and expectations in their role to be creative (Lavranos et al., 2015; Kostagiolas et al., 2017), their training in music, type of ensemble, and years of experience as conductor.

Social context

The social context considers the individual’s setting, situation, existing knowledge, and connections with other people (Agarwal, 2017; Wilson, 2022, p. 17). The social context of an individual emphasises how they interact with their environment, information objects, and individuals surrounding them (Agarwal, 2017, p. 9; Wilson, 2022, p. 17). Through socialisation an individual utilises various communication channels (face-to-face, online, email, etc.) to interact and understand their surroundings (Agarwal, 2017, p. 12; Given et al., 2023; Savolainen, 2012) and to seek information. A conductor needs to be able to communicate with their ensemble as their leader while also considering their ensemble’s preferences, interests, and values to encourage understanding and learning (Rotjan, 2021; Nielsen et al., 2023).

Activities context

The seeking, searching, retrieval, sharing, usage, and transfer of information is part of the activities’ context (Meyer, 2018). It includes the choices and use of information sources. The activities context is impacted by the individual’s environment, personal, and social contexts (Meyer, 2018; Savolainen, 2012). For a music conductor this would be the selection of repertoire as well as rehearsing and performing the selected repertoire while also considering the possible cultural impact the selected repertoire might have (Apfelstadt, 2000; Nûñez, 2012). Bearing these influences in mind, an individual conductor has the option to pursue or abandon their information need e.g., to find a specific piece of sheet music. As has been shown in research findings, the other contexts will also influence choices and actions, allowing for the information need to be resolved or forgotten (Meyer, 2018; Savolainen, 2012).

For the purpose of our exploratory study, models that emphasise the context in which professionals such as conductors fulfil their role for a specific core process, repertoire selection, was important. We decided on the eclectic use of the Wilson (1981) and Leckie et al. (1996) models to guide the collection of data. The questionnaire for data collection is shown in Appendix I and the interview schedule in Appendix II.

Methods

The exploratory study we report on in this paper was conducted in 2023. We followed a mixed method approach, making use of an online questionnaire (cc Appendix I) and online interviews according to an interview schedule (cc Appendix II) to respectively collect quantitative and qualitative data. The questionnaire was distributed online via five Facebook communities for music conductors (Choral Repertoire Hub, Orchestra music, etc). Emails to invite conductors to participate were also send to the personal contacts of the first author (Firkins) and in particular, the second author (Barrett-Berg) who is a conductor with many personal connections. Ethical clearance to conduct the study was obtained from the University of Pretoria (UP), Engineering, Built Environment & Information Technology (EBIT) Faculty’s Committee for Research Ethics and all participants had to sign a form to give informed consent for voluntary participation. The sample group for the research consisted of music conductors (choral, orchestral). They were recruited locally as well as internationally e.g., from the USA and Catalan. The majority of the responses received for the questionnaire were from choral conductors. The questionnaire and interviews were conducted online to accommodate the participant’s geographical location. A Google Form link was distributed on the platforms and personal emails as part of the research cover letter.

The online questionnaire (cc Appendix I) consisted of open- and closed-ended questions focusing on three aspects of the repertoire selection process (scoring, ensemble, acquisition of music sheets) as well as the conductor’s experiences, barriers and the impact it had on information seeking. The questionnaire had five sections, namely descriptive questions/demographic, scoring and ensemble repertoire selection components, sheet music acquisition, repertoire selection process, and voluntary optional additional information relevant to the study’s topic. By starting with the contexts (cc Importance of Context in Information Behaviour Research and Relevance for Music Conductors) the intention was to collect data on how the environment and personal characteristics and perceptions of the process of repertoire selection serve as context for the information seeking activities, e.g., choices of information sources and personal interaction to find information.

The questionnaire received a total of 37 responses including 34 responses from choral and 3 responses from orchestral conductors. The questionnaire collected mostly descriptive quantitative data. The closed-ended questions asked the respondents to categorise the given scoring components, ensemble components, and acquisition methods making use of a Likert scale from 1 (very important) to 5 (least important). Each question also allowed respondents to select (N/A) if the question was not applicable to them. Due to the requirements of the institution (University of Pretoria) for ethical clearance we did not ask typical demographical questions such as age. The open-ended questions mainly allowed the respondents to add more detail or add other components and/or methods that was not included on the categorisation part of the questionnaire.

The interview followed a semi-structured approach focusing on the entire repertoire selection process while also touching upon how the conductors get inspired, the impact of possible external factors/barriers and the impact on their information seeking behaviour. The intention was to collect qualitative data. Only two questionnaire respondents, Alex and Blake (pseudonyms), volunteered to be interviewed. The interviews were conducted online (30-40-minute sessions) with written participant consent to record the Zoom meetings. We acknowledge, that we were hoping to include more participants for the interviews, but due to time constraints to complete the study and to avoid pressuring the questionnaire participants, we decided to include the interview input to enrich the questionnaire feedback and to identify further research needs, e.g., the development of a database consisting of old and new pieces. This fitted with the exploratory purpose of the study. Their input highlighted the role inspiration plays in repertoire selection and the subsequent information seeking.

For the two interviewees, pseudonyms were used, but for the data collected through questionnaires, participants were labelled as Respondent 1, Respondent 2, etc.

Principles of thematic analysis as explained by Braun and Clarke (2012, p. 57) were applied to analyse the responses to the open-ended questions and the interviews. They define thematic analysis as ‘a method for systematically identifying, organising, and offering insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across a data set’.

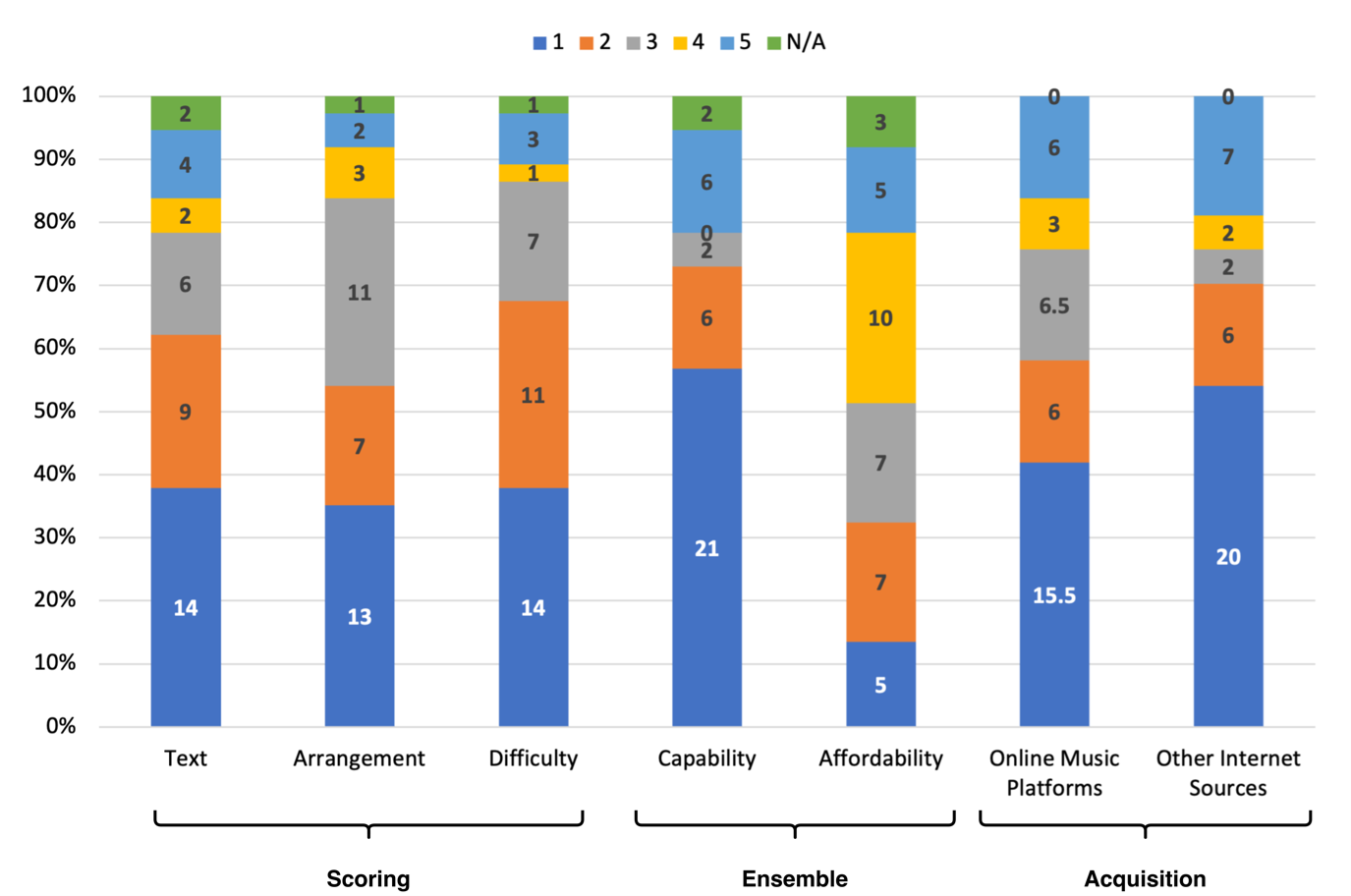

Figure 1 reflects only what we learned with regard to information seeking behaviour and repertoire selection as a core process for the role of conductor.

Results and discussion

The data collection revealed components such as influencing factors (Meyer, 2018) (for this study it included scoring, ensemble) and methods (e.g. information seeking, encountering information; for this study methods include acquisition e.g., of sheet music). The components and methods utilised by conductors throughout their respective repertoire selection processes were related to their information seeking behaviour. The quantitative data revealed typical tasks requiring information and issues to consider in repertoire selection (e.g., text, ensemble capabilities), internet usage and other information seeking activities and sources. By implication, issues to consider influences further actions such as deciding what is relevant to an information need and what to acquire. The qualitative data revealed factors influencing repertoire selection and information seeking e.g., repertoire inspiration and financial factors. Not all findings will be discussed in this paper; only a selection of findings relevant to the repertoire selection process, contexts and information seeking are highlighted.

The quantitative and qualitative data were jointly considered to identify three categories that showed potential. These are the (i) process of repertoire selection (i.e., related to the role and task of the conductor) (activity context and social context), (ii) conductor’s (individual) influence (i.e., personal context), and (iii) external factors (that can form part on the environmental context). This paper identified and discusses several influences on the repertoire selection process.

Repertoire selection process

A conductor’s repertoire selection process consists of various scoring and ensemble components that need to be considered before deciding on how the sheet music that will be utilised will be acquired (i.e., the information seeking methods used to identify and gather sheet music). Three components of conducting are of particular importance, namely, scoring, ensemble, and acquisition methods. Figure 1 portrays the most important details for relevant scoring components (text, arrangement, difficulty), ensemble components (capability, affordability), and acquisition methods (online music platforms, other internet sources).

Figure 1. Most relevant scoring components, ensemble components, and acquisition methods

Each aspect categorised (scoring, ensemble, acquisition) consisted of multiple options (cc Appendix I), however only the most relevant aspects are discussed for the purpose of this paper. All questionnaire respondents were asked to categorise the provided components and methods (cc Appendix I), Figure 1 depicts the components and methods that were categorised largely as the most important (categorised mainly as 1). The different colours depicted in Figure 1 symbolise the categorisation and the number of respondents who indicated the component(s) and method(s) using the Likert scale. If none of the respondents categorised a component and/or method, Figure 1 depicts them as zeros.

The three scoring components identified are text, arrangement, and difficulty. Fourteen respondents categorised Text and Difficulty as very important while thirteen respondents categorised Arrangement as very important. Choral conductors focus on the message (Text) conveyed by the lyrics and the composer’s motivation for composing the piece of music (Respondents 15, 17, 20). For example, if a conductor leads a children’s choir, the appropriateness of the lyrics within a song and in conjunction with the age of the singers needs to be considered, as well as the occasion and audience for which the songs will be performed. Arrangement considers the voice/instrument division and the need for piano/instrumental accompaniment. Finally, the Difficulty of the piece selected plays a pivotal role when selecting sheet music. The time signature (essential the pulse or beat of the song), tempo (speed) and range (from the lowest to highest note) all contribute to the difficulty of the piece. The text and language of the piece can also contribute to this difficulty. In their study Hedden and Allen (2019, p. 18) concluded that the text and the arrangement of voices were the most important components considered when selecting repertoire. In our exploratory study Respondents 13 and 15 reported that the ensemble’s overall enjoyment of the repertoire selected also needs to be considered when looking at the scoring of sheet music.

An ensemble’s capability also needs to be considered by the conductor when selecting the repertoire. Twenty-one respondents confirmed that the ensemble’s Capability is very important and determines what the ensemble can musically accomplish (confirmed by Respondent 16). If an orchestra consists of professional musicians, the difficulty level of selected pieces can be higher than an amateur school orchestra. Brinson (1996, p. 80-81) was the only publication found that considered ensemble components such as size, maturity, and texture. Brinson (1996) identified that the ensemble itself impacts the selection of repertoire, since the pieces selected need to be rehearsed and performed by that specific ensemble.

Advancements in technology and what is accessible on the internet has drastically developed and changed the acquisition methods utilised by conductors around the world (Chandler, 2019, p. 90; Chen, 2018, p. 80). Although both online music platforms and other internet sources refer to internet platforms, the distinguishing factor is online music platforms such as online streaming platforms, sheet music platforms (e.g., Sheet Music Plus), etc., while other Internet sources refer to a music composer’s personal profile/webpage, collaborative communities (e.g., Facebook communities), etc. In Figure 1, Online Music Platforms is a combination (49% categorising both between important to most important) of two methods categorised from the questionnaire (online publishers, and online streaming and YouTube) (cc Appendix A). A conductor would e.g., look at what sheet music is available on an online publisher’s platform while/after listening to recordings on various online streaming platforms, e.g., Apple Music, Spotify, YouTube, etc. This was confirmed by Respondent 21 and Respondent 33. However, access to the Other Internet Sources does not restrict conductors to online publisher platforms of streaming platforms; they can also access composers’ personal websites, other ensembles’ repertoires, and various lists and catalogues that are available on the Internet, e.g. making use of databases that consist of compositions by minority composers, confirmed by Respondent 16. There are thus many ‘Other Internet options’ as well. This was confirmed by both Respondent 12 and 17. Some respondents also mentioned that they utilise their personal libraries and attend live performances, workshops, competitions, etc. to get inspired and identify new repertoire.

Apart from the findings shown in Figure 1, the results also emphasised that a conductor’s repertoire selection is also influenced by their social contexts and activities. When selecting repertoire, a conductor can communicate with other conductors to assist in the selection of music that is relevant and achievable for their ensembles. The level of communication and socialisation possibly impacts the interpretation of pieces selected. From the participant’s input to the questionnaire (cc Appendix I) it was also clear that the selection process cannot exist without considering the conductor’s personal influence (experiences, inspiration, training) and the influence of external factors experienced throughout.

Conductor’s influence

The conductor’s experiences and repertoire inspiration contribute and influence their overall repertoire selection process and the repertoire they eventually select. A study by Brinson (1996) briefly mentions the impact of a conductor’s previous experiences and what inspires them on this selection process, without providing detail.

Fourteen questionnaire respondents identified that they have been a professional conductor (i.e., getting paid to be a conductor) for 21+ years. Such experience is not restricted to their conducting experience but can include being part of ensembles or a solo career as musicians. Respondent 36 confirmed that by being part of an ensemble, an overall idea can be formed regarding repertoire selection and what components to consider throughout the selection process. Most respondents reported that they have undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications in music, specialising in conducting. Two respondents did not have formal training in music or conducting; they did not identify a lack of experience as a hindrance to fulfil the role.

During the interviews, the two participants (Alex and Blake) elaborated on the role inspiration has when conductors select repertoire which would lead to the seeking of, e.g., sheet music, recordings, etc. Choosing music based on thematic concepts is common and can range from more broad concepts e.g. 'nature' (Blake), to more specific themes e.g. 'birds' (Alex). A conductor’s repertoire inspiration allows for the selection of several pieces that are connected literally or metaphorically. The selection of pieces relevant to the inspired theme do not need to be in the same genre, tempo, or for the same composer, but tell a story (as stated by Respondent 36). Each conductor also has their own style and speciality, allowing for infinite combinations of pieces coming from the same or similar themes (according to Respondent 9 and Respondent 11). According to Alex, inspired themes allow for conductors to find and discover unknown composers whose music may be relevant to their selected theme. A conductor’s information need is impacted/influenced by their repertoire inspiration e.g. if repertoire is being selected for younger singers, the music and lyrics is relatable to their own experiences and understanding (according to Respondent 11), the singers need to feel represented through the music (according to Respondent 16). If a conductor is not inspired, the selection of repertoire cannot be accomplished to its fullest potential.

The conductor’s influence can be placed in the personal context previously discussed (cc Importance of Context in Information Behaviour Research and Relevance to Music Conductors). The conductor’s past experiences influence their mindset in combination with their demographics. The ensemble’s demographics play an integral part as well. A conductor’s personal context is unique and is not going to be the same as another individual’s past experiences and repertoire inspiration (articulated by both Alex and Blake).

External factors

Respondents reported many external factors that influence their repertoire selection and information seeking. These are depicted in Table 1 and range from finances to ensemble/group values and timing. According to the questionnaire responses and interviews, finances play a pivotal role for every conductor. The option Affordability under Ensemble in Figure 1 does not fully reflect the importance of finances. Such importance only came out in the answers to questions regarding the barriers faced throughout the repertoire selection process. Affordability and Finances considers the cost of purchasing sheet music (Respondent 15) as well as the cost of running the ensemble itself (according to Blake). Questionnaire respondents mainly focused on the financial aspects of purchasing the sheet music rather than the running of the ensemble. Brinson (1996) and Collins (1999) also noted the impact of finances on the overall repertoire selection process (but without going into detail). A few respondents situated in South Africa identified the lack of a sheet music infrastructure in the country, meaning they need to purchase sheet music internationally in foreign currency. The latter was especially stressed by Respondent 7 and Respondent 20. Apart from the influence of religion and other demographics (Respondent 2 and Respondent 23) there are many other external influences such as organisational/institutional influences and the ensemble’s values, which are considered by conductors when selecting music. Such influences or potential barriers need to be explored by means of further qualitative research to gain a fuller understanding.

| Barriers | Number of mentions in questionnaire responses |

|---|---|

| Finances | 14 |

| Sheet music availability | 9 |

| Religion & demographics | 7 |

| Organisational/institutional | 5 |

| Selection of sheet music | 5 |

| Ensemble/group’s values | 3 |

| Timing | 3 |

Table 1. Overall barriers to repertoire selection identified

The external barriers experienced by conductors are impacted by their environmental context (cc Importance of Context in Information Behaviour Research and Relevance to Music Conductors). As shown in Table 1 conductors experience various barriers. These may impact on their information seeking activities e.g., if they cannot acquire the sheet music they would need to find a new piece of music or change the entire repertoire (corroborated by Respondent 2 and Respondent 13). If a conductor does not have the funding needed to select the desired music, their repertoire inspiration will need to adapt to their environment (i.e., to music they can afford) to allow for them to accomplish their selection process (corroborated by Respondent 3 and Respondent 20).

Discussion and nascent model of how the repertoire selection process links to information seeking

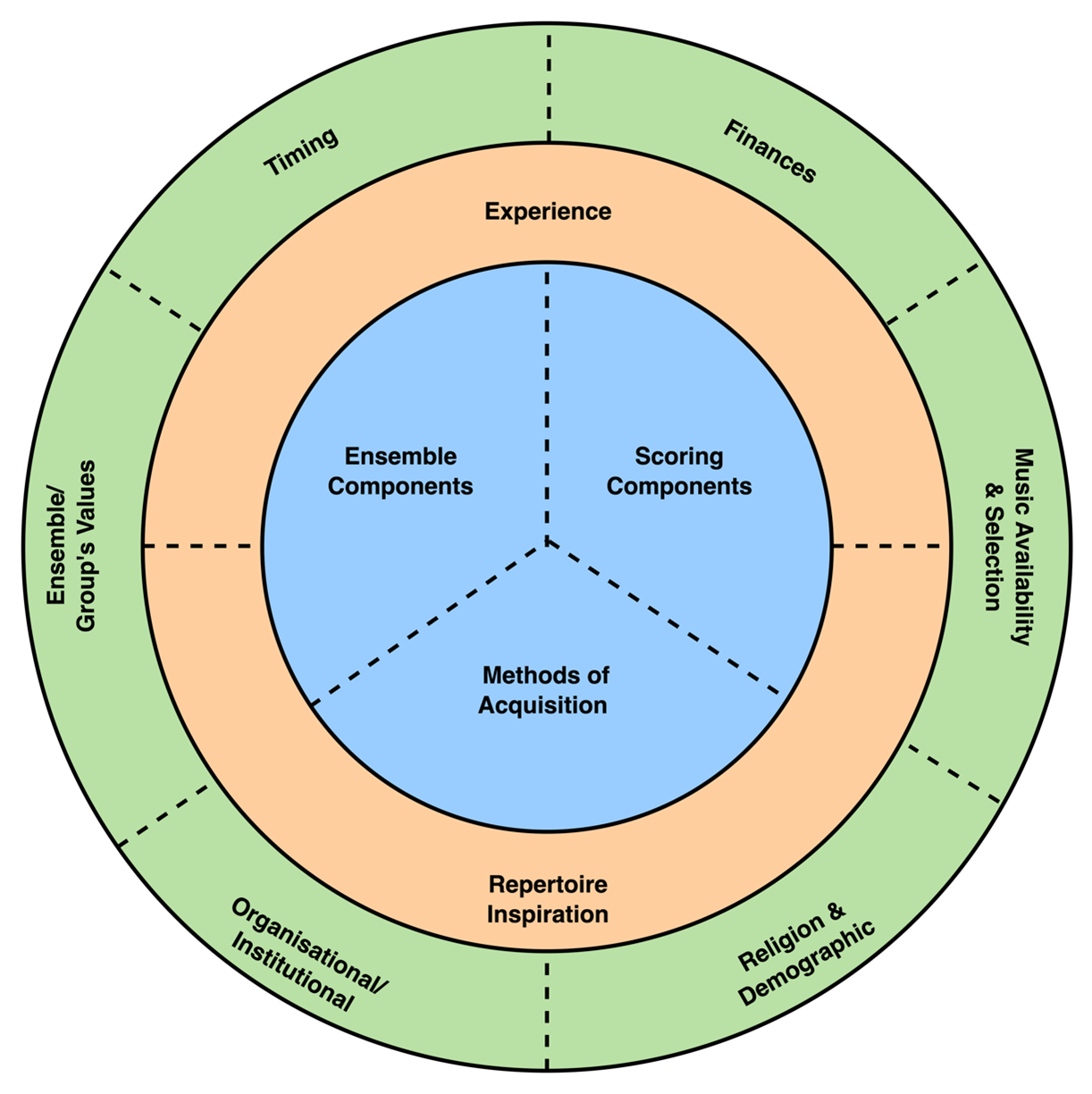

This paper reports only on a small selection of findings from the 2023 exploratory study and more specifically only on findings relevant to the repertoire selection process. Based on these findings we would like to propose a nascent model (i.e., a model that is still under development and that would be further refined based on the full results as well as further research). The model proposed in Figure 2 focuses on the most important process in the role of a conductor (i.e., on the repertoire selection process) and the (i) activities; (ii) individual; (iii) barriers.

Under Method we explained that the exploratory study was guided by eclectic use of the Wilson (1981) and Leckie et al. (1996) models. These models influence the data we collected (cc Appendix I, Appendix II). The nascent model depicted in Figure 2 focuses specifically on a role related to a profession (i.e., conductor [Leckie et al. (1996) model]) as aligned with context(s) (derived from Wilson (1981) model and other information behaviour researchers). (Although mentioned and implied, context is not explicitly depicted in the Leckie et al. (1996) model.)

By presenting our findings on this small component of the exploratory study in a circular form (cc Figure 2), it becomes clear that there is not a rigid structure or linear cycle in the selection of repertoire and by implication also not in the information seeking to acquire sheet music. It further illustrates that there is fluidity between all sections of the repertoire selection process. There are many influences and barriers which could result in a conductor adapting/changing their initial selections of sheet music.

Figure 2. Nascent model of the repertoire selection process that impacts on information seeking

The blue circle represents the core elements of the repertoire selection process (i.e., scoring components, ensemble components, methods of acquisition), the orange circle represents the core elements of the conductor’s influence (i.e., experience, repertoire inspiration) and the green circle represents the core external factors that might also act as barriers. The elements from each circle can influence other circles, thus the use of the dotted line, further establishing the fluidity of the repertoire selection process. Each conductor’s repertoire selection process is different and does not follow the same method or structure. A conductor could consider the external factors before acquiring the sheet music. Another conductor could first consider the scoring components most relevant to their ensemble while keeping all institutional guidelines in mind. At this stage Figure 2 does not reflect the details of the fluidity of each conductor’s own method of selecting repertoire. A possible next step would be to apply a similar approach to other roles of conductors e.g. rehearsing for performances or negotiating performance contracts or understanding the ensemble’s community and possible audience.

At this stage we have not yet mapped information seeking behaviour concepts to the model. We noted some preliminary findings e.g. repeating the process if there are not funds to acquire the necessary sheet music (i.e., organisational barrier) or using either online platforms or other Internet sources to do the same. If we add such detail at this stage, the value of the circular interpretation of a core process in a professional role (where there are also other roles), would be lost.

When considering Wilson’s (1981) general information behaviour model, information needs and information seeking stand out with reference to the person and role components/contexts, which have been swapped in Figure 2 (i.e., the central and middle sections of the model). The role of a conductor (in part) is to select repertoire that resonates with their ensemble while considering the scoring and where to acquire the necessary sheet music. The personal component is the conductor’s influence on the repertoire selection process. Showcasing how their previous experiences impacted and allowed for their selection process to evolve, as well as how they get inspired to construct a well-balanced repertoire. Finally, the environmental component focuses on the external factors which impact the conductor’s overall influence on the repertoire selection process. Leckie et al.'s (1996) model made use of a feedback loop, allowing for an information need to be refined and/or redefined so that it can allow for the identification and capture of relevant information sources. Within the proposed repertoire selection process, the feedback loop is implied due to the fluidity between the circles. After consideration of other findings, we might make this more explicit.

Conclusion

Music repertoire selection’s interdependence with other tasks of music conductors identifies the importance of individuality and inevitable external factors, which influence information seeking. By focusing on choral and orchestral conductors, a broad overview has been accomplished, e.g., choral conductors heavily emphasise the text/lyrics of pieces as well as the arrangement of sheet music to ensure it can be accomplished by their ensemble, whereas orchestral conductors emphasise the instrumentation and quality of the sheet music. Due to the small number of orchestral conductors participating in the study, further research from a larger sample size would be beneficial in understanding their specific needs and perspectives. Increasing the number of interviews would also be beneficial to enhance the understanding of the qualitative data, especially the importance of repertoire inspiration that forms part of a conductor’s role. Finally, a comparative study between the needs of orchestral versus choral conductors when seeking repertoire will add great value to literature.

The exploratory study did not determine a standardised repertoire selection process that conductors follow. It did, however, reveal how different types of contexts, the individual characteristics and experiences of the conductor, and external barriers impact on the repertoire selection process and thus also on information seeking. Further work needs to focus on other roles, mapping the information seeking behaviour and in particular, the role of creativity and input from both types of conductors.

About the authors

Christina Firkins is an assistant lecturer at the University of Pretoria in the Department of Information Science. She has an honours degree in Information Science and is completing a master’s in information technology, focus on Information Science, with prospects of continuing to doctorate level. The research presented in this paper is based off her master’s dissertation titled Information Seeking Behaviour of Music Conductors within the Repertoire Selection Process. She has been part of choirs since 2007 till 2021 and was part of her high school orchestra in 2017. She has knowledge in music theory (UNISA grade 5) and musical instruments (recorder, piano, oboe) with her main instrument being classical voice (Trinity grade 8). Email: christina.firkins@up.ac.za

Dr Michael Barrett-Berg is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Pretoria, and conductor of the Internationally award winning Tuks Camerata Choir. He holds a Y2 Rating from the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) for his research, which primarily focuses on the value of choral music within a diverse setting, as well as the authentic performance practices of traditional South African choral music. He currently serves on the Advisory Boards of both the World Choir Council (Interkultur) and the World Journal for Choral Research, Practice and Leadership. Michael is also the co-founder and conductor of South Africa's largest community choir, The Capital Singers. Email: michael.barrett@up.ac.za

Dr Ina Fourie is a Full Professor and experienced information behaviour researcher, Chair-Elect of the iSchool Board, EXARRO Chair in Extended Reality (XR) (University of Pretoria) and former Head of the Department of Information Science and Chair of the School of Information Technology (iSchool), University of Pretoria. She served on the ISIC steering Committee (2016-2023) as secretary and vice-chair. Her core research interest is health information behaviour, palliative care, grief and bereavement. Email: ina.fourie@up.ac.za

References

Agarwal, N.K. (2017). Exploring context in information behaviour: seeker, situation, surroundings, and shared identities. Springer International Publishing AG.

Apfelstadt, H. (2000). First things first selecting repertoire: finding quality, teachable repertoire appropriate to the context, compatible with the national standards, and interesting to play is an achievable goal. Music Educators Journal, 87(1), 19-46. https://doi.org/10.2307/3399672

Atchison, S.-L. (2015). From selection to the stage: an introduction to repertoire selection for the new director. https://www.nfhs.org/media/1016784/4-16.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20240414070241/https://www.nfhs.org/media/1016784/4-16.pdf)

Bates, M. J. (1989). The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Review, 13(5), 407–424. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1108/eb024320

Biasutti, M. (2012). Orchestra rehearsal strategies: conductor and performer views. Musicae Scientiae, 17(1), 57-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864912467634

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H.E. Cooper, P.M. Camic, D.L. Long, A.T. Panter, D.E. Rindskopf & K.J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57-71). American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Brinson, B.A. (1996). Choral music methods and materials: developing successful choral programs (grades 5 to 12) (1st. ed.). Schirmer Books.

Bronstein, J., & Lidor, D. (2021). Motivations for music information seeking as serious leisure in a virtual community: exploring a Eurovision fan club. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 73(2), 271-287. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-06-2020-0192

Brown, E. (2015). A dictionary for the modern conductor. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Burdukova, P. (2010). An analysis of the status of orchestras in South Africa. (Unpublished MMus dissertation). University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. https://www.nfhs.org/media/1016784/4-16.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20240414071721/https://repository.up.ac.za/handle/2263/28254)

Byström, K. & Järvelin, K. (1995). Task complexity affects information seeking and use. Information Processing & Management, 31(2), 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(95)80035-R

Case, D.O. & Given, L. (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (4th. ed.). Emerald Group Publishing.

Chandler, M. (2019). The information searching behaviour of music directors. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 14(2), 85-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.18438/eblip29515

Chen, Y. (2018). An investigation of middle school music teachers’ rationale and procedure relating to instrumental (band) repertoire selection in southern Ontario: a case study. (Unpublished master thesis). University of Windsor, Ontario, Canada. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7421/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20240322072935/https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7421/)

Collins, D.L. (1999). Teaching choral music (2nd. ed.). Pearson.

Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind’s eye of the user: The sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. Qualitative research in information management, 9(1), 61–84.

Ellis, D. (1989). A behavioural model for information retrieval system design. Journal of Information Science, 15(4-5), 237-247. doi: 10.1177/016555158901500406

Fena, C. (2021). Searching, sharing and singing: understanding the information behaviors of choral directors. Journal of Documentation, 77(1), 199-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-05-2020-0087

Fourie, I. & Julien, H. (2014). Ending the dance: a research agenda for affect and emotion in studies of information behaviour. Information Research, 19(4), 108-124. http://informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic09.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191227031347/http://informationr)

Freund, L. (2015). Contextualizing the information-seeking behavior of software engineers. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(8), 1594-1605. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23278

Given, L.M., Case, D.O. & Willson, R. (Eds.). (2023) Looking for information: examining research on how people engage with information. Emerald Publishing Ltd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S2055-5377202315

Hedden, D.G. & Allen, A.D. (2019). Conductors’ literature selection practices for community children’s choirs in North America. International Journal of Music Education, 37(1), 3-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0255761418787539

Hektor, A. (2001). What’s the use?: Internet and information behavior in everyday life. Linköping Studies in Arts and Science, vol. 240.

Hopkins, M. (2013). Programming in the zone: repertoire selection for the large ensemble. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 69-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432113480184

Hunter, B. (2006). A new breed of musicians: the information-seeking needs and behaviours of composers of electroacoustic music. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 10(1), 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J116v10n01_01

Ikoja-Odongo, R. & Mostert, J. (2006). Information seeking behaviour: a conceptual framework: research article. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 72(3), 145-158. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC139832

Jansson, D., Elstad, B. & Døving, E. (2021). Choral conducting competences: perceptions and priorities. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(1), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X19843191

Kostagiolas, P., Lavranos, C., Korfiatis, N., Papadatos, J. & Papavlasopoulos, S. (2015). Music, musicians and information seeking behaviour: a case study on a community concert band. Journal of Documentation, 71(1), 3-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2013-0083

Kostagiolas, P., Lavranos, C., Martzoukou, K. & Papadatos, J. (2017). The role of personality in musicians’ information seeking for creativity. Information Research, 22(2), paper 756. http://InformationR.net/ir/22-2/paper756.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6r2RN8X1H)

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199106)42:5<361::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-%23

Kuhlthau, C. C. (2004). Seeking meaning: A process approach to library and information services (Vol. 2). Libraries Unlimited Westport, CT.

Laplante, A. (2008). Everyday life music information-seeking behaviour of young adults: an exploratory study. McGill University. (University of McGill Ph.D. dissertation) https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/2514np20z (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20231204123715/https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/2514np20z)

Lavranos, C., Kostagiolas, P., Martzoukou, K. & Papadatos, J. (2015). Music information seeking behaviour as motivator for musical creativity: conceptual analysis and literature review. Journal of Documentation, 71(5), 1070-1093. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2014-0139

Leckie, G., Pettigrew, K. & Sylvain, C. (1996). Modeling the information seeking of professionals: a general model derived from research on engineers, health care professionals, and lawyers. The Library Quarterly, 66(2), 161-193. https://doi.org/10.1086/602864

Lugović, S. (2022). Recognition of user information behavior through music-related information searching patterns. (University of Zagreb Ph.D. dissertation). http://dx.doi.org/10.17234/diss.2022.7908

Lüsted, M. (2011). Entertainment (Inside the Industry). ABDO Publishing Company.

Matthews, W.K. & Kitsantas, A. (2007). Group cohesion, collective efficacy, and motivational climate as predictors of conductor support in music ensembles. Journal of Research in Music Education, 55(1), 6-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242940705500102

Meyer, H. (2016). Untangling the building blocks: a generic model to explain information behaviour to novice researchers. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Zadar, Croatia, 20-23 September, 2016: Part 1. Information Research, 21(4), paper isic1602. http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/isic/isic1602.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6mHhVYy54)

Meyer, H.W. (2018). Understanding the building blocks of information behaviour: a practical perspective. Innovation: Journal of Appropriate Librarianship and Information Work in Southern Africa, 2018(56), 24-50. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC-104df811b6

Moore, T.R. (2021). The instrumentalised conductor. TEMPO, 75(297), 48-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S004029822100022X

Munro, K., Ruthven, I. & Innocenti, P. (2022). DJing as serious leisure and a higher thing; characteristics of the information behaviour of creative DJs. Brio: Journal of the UK Branch of the International Association of Music Libraries, 59(1), 1-18, article 80333.

Nielsen, S.G., Jordhus-Lier, A. & Karlsen, S. (2023). Selecting repertoire for music teaching: findings from Norwegian schools of music and arts. Research Studies in Music Education, 45(1), 94-111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X221099436

Núñez, F.J. (2012). The Cambridge companion to choral music. In A. De Quadros (Ed.), (1st ed., p. 203-215). Cambridge University Press.

Nwokenna, E.N., Amanambu, O.V., Umeano, B.C., Oloidi, F.J. & Vita-Agundu, U.C. (2022). Educational information need of undergraduate music students. Library Philosophy & Practice, article 7083. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=13730&context=libphilprac (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20230801093841/https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=13730&context=libphilprac)

Phillips, K.H. (2004). Directing the choral music program (1st. ed.). Oxford University Press.

Robson, A., & Robinson, L. (2013). Building on models of information behaviour: linking information seeking and communication. Journal of Documentation, 69(2), 169-193. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411311300039

Rotjan, M. (2021). Deciding for or deciding with: student involvement in repertoire selection. Music Educators Journal, 107(4), 28-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/00274321211013879

Rousi, A., Savolainen, R. & Vakkari, P. (2016). A typology of music information for studies on information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 72(2), 265-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-01-2015-0018

Savolainen, R. (2012). Conceptualising information need in context. Information Research, 17(4), paper 534. http://InformationR.net/ir/17-4/paper534.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20160425134300/http://www.informationr.net/ir/17-4/paper534.html#.Vx4e6HbP32c)

Shrock, D. (2009). Choral repertoire (1st ed.). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Stamer, R.A. (2002). Choral ensembles for independent musicianship. Music Educators Journal, 88(6), 46-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3399805

Tarasti, E. (1994). Music models through ages: A semiotic interpretation. International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 25(1/2), 295–320. http://www.jstor.org/stable/836948

Titze, I.R. & Maxfield, L. (2017). Acoustic factors affecting the dynamic range of a choir. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 142(4), 2464-2468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1121/1.5004569

Tubachi, P. (2018). Information seeking behavior: an overview. ResearchGate, article 330521546. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330521546_INFORMATION_SEEKING_BEHAVIOR_AN_OVERVIEW (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20230213092203/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330521546_INFORMATION_SEEKING_BEHAVIOR_AN_OVERVIEW)

Vakkari, P. (2008). Trends and approaches in information behaviour research. Information Research, 13(4), paper 361. http://InformationR.net/ir/13-4/paper361.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20230314155419/https://www.informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper361.html)

Wilson, T. (1981). On user studies and information needs. Journal of Documentation, 37(1), 3-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb026702

Wilson, T. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249-270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007145

Wilson, T. (2000). Human information behavior. Informing Science, 3(2), 49-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.28945/576

Wilson, T. (2022). Exploring information behaviour: an introduction. Information Research. https://informationr.net/ir/Exploring%20information%20behaviour.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20230615060044/https://informationr.net/ir/Exploring%20information%20behaviour.pdf)

Yarbrough, C. (1975). Effect of magnitude of conductor behavior on students in selected mixed choruses. Journal of Research in Music Education, 23(2), 134-146. https://doi.org/10.2307/3345286

Appendix I

Questionnaire

Informed Consent Form

Dear Respondent,

You are invited to participate in a survey titled ‘Information Seeking Behaviour of Music Conductors within the Repertoire Selection Process’, conducted by Christina Firkins. The research is in partial fulfilment of the MIT Degree in Information Science at the University of Pretoria (UP). The research is supervised by Dr M. Barrett-Berg and Prof I. Fourie.

The survey you have received has been designed to study the repertoire selection process of music conductors (choral and orchestral). The aim of this research is to better understand the overall process, which includes considering many variables and overcoming challenges pertaining to the selection procedure.

You have been invited to participate in this study as your experience and views related to this topic are of value and importance and will assist the researcher to gain an in-depth understanding of the area under investigation.

By completing this survey, you agree that the information you provide may be used for research purposes, including dissemination through peer-reviewed publications and conference proceedings. You are, however, under no obligation to complete the survey and you may withdraw from the study at any time without any prejudice. The survey is anonymous and has been developed in such a way that no connection can be made between the respondent and the research team. If you choose to participate in this survey it will take approximately 20 minutes to complete.

This research aims at providing an understanding and awareness to the multifaceted approach to repertoire selection, which will be beneficial to conductors and administrators alike. There are no foreseeable negative consequences associated with participation, nor will respondents be compensated or incentivised in any way. The researcher undertakes to keep any information provided herein confidential, not to let it out of their possession and to report on the findings from the perspective of the participating group, the perspective of the collective rather than the individual’s perspective. The records will be kept for ten years for audit purposes where after they will be permanently destroyed.

The research has been reviewed and approved by the University of Pretoria’s EBIT Research Ethics Review Committee. If you have any concerns, please contact the researcher at the details below.

Regards

Christina Firkins

Contact details: The researcher can be contacted at christina.firkins@up.ac.za or u18169733@tuks.co.za.

By selecting “Yes” I hereby voluntarily grant permission for participation in this anonymous survey. I understand the nature and objectives of this research which has been explained to me.

Are you a professional orchestral/choral conductor – in other words – you are paid for leading/conducting an orchestra(s)/choir(s)?

Yes

No

I understand my right to choose whether or not to participate in this research project, and that the information provided will be handled confidentially. I am aware that the results of the survey may be used for academic publication.

Yes

No

Questionnaire

Section A: Descriptive questions/Demographic

Are you primarily a conductor/educator for:

Choirs/voice ensembles/singing groups

Instrumental ensembles/bands/orchestras

How many years have you been a professional conductor (i.e., paid for your services)?

0-5 years

6-10 years

11-15 years

16-20 years

21+ years

Keeping your primary profession in mind (as answered in question 1 above), how many ensembles do you conduct annually? For example, if you are primarily a choir conductor, please only include all choir/vocal ensembles/singing groups and similarly for instrumental groups.

3.2. If you conduct more than one primary group, is your process of repertoire selection the same? If no, please elaborate.

Have you had any formal music training? (Choose all that apply)

High school (subject music, individual instrumental lessons, music theory, etc.)

Certificate or diploma received from a higher institution of learning

Undergraduate degree in music

Postgraduate degree in music

No formal training

Do you have any formal training in conducting (orchestral or choral)?

Yes

No

5.1. By answering question 4.1 (one or more options selected) and 4.2 (yes or no), did you feel that your involvement in music/conducting prepared you in anyway regarding the selection of repertoire for your ensemble? Kindly elaborate.

5.2. If you answered none/no to question 4 4.1 and 4.2 respectively, what strategies have guided you in the selection of repertoire to date?

Section B: Scoring and Ensemble Repertoire Selection Components

What is the single most important aspect which you consider before selecting a piece for your ensemble?

From the list below, what aspects pertaining specifically to the music do you consider before selecting repertoire? Categorise each from most important (1) to least important (5). If not applicable, categorise as N/A.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | N/A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | ||||||

| Tessitura | ||||||

| Text | ||||||

| Accompaniment | ||||||

| Arrangement | ||||||

| Transcription | ||||||

| Difficulty |

Are there any components that you consider that were not mentioned in the list above? Please categorise other components provided using the same numbering system (1 – most important, 5 – least important).

From the list below, what aspects pertaining specifically to the ensemble do you consider before selecting repertoire? Categorise each from most important (1) to least important (5). If not applicable, categorise as N/A.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | N/A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | ||||||

| Maturity | ||||||

| Texture | ||||||

| Capability | ||||||

| Context | ||||||

| Affordability |

Are there any components that you consider that were not mentioned in the list above? Please categorise other components provided using the same numbering system (1 – most important, 5 – least important).

Section C: Sheet Music Acquisition

What is your main source/s of collecting information/inspiration for acquiring sheet music to include into your repertoire? Categorise each from most frequent (1) to least frequent (5). If not applicable, categorise as N/A.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | N/A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live performances/competitions/festivals | ||||||

| Conventions/symposia | ||||||

| Colleagues | ||||||

| Online music publishers | ||||||

| Music retailers/stores | ||||||

| Professional journals, textbooks, anthologies | ||||||

| Recordings/radio/online streaming platforms/YouTube | ||||||

| Social media (TikTok. Facebook, Instagram, etc.) | ||||||

| Internet searches/browsing | ||||||

| Film, reality music competitions, etc. | ||||||

| Other: |

Has your method of acquisition changed/evolved throughout your professional conducting career?

Yes

No

If yes, why would you say your acquisition method has changed/evolved?

If no, why would you say your acquisition method has not changed/evolved?

To what lengths do you go to find music which is not easily/readily available?

Section D: Repertoire Selection Process

Would you consider the scoring, the ensemble, and the music acquisition as equally important throughout the repertoire selection process?

Yes

No

If no in 12.1, how would you categorise scoring, ensemble, and music acquisition from most important to least important? Why?

What are other barriers you might experience throughout the repertoire selection process, excluding scoring, ensemble, and music acquisition? For example; finances, organisational, institutional, religious, etc. Please categorise the barriers identified with scoring, the ensemble, and music acquisition from most important (1) to least important (5).

14.1. Would you state that the barriers mentioned in 13 (above) impact your repertoire selection process more than scoring, ensemble, and music acquisition?

Yes

No

14.2. Why did you answer question 14.1 (above) as yes/no?

Section E: Voluntary Research Feedback

Thank you for setting aside some time and completing this online survey. If you are interested in the research and would like to stay up to date, please feel free to contact the researcher at any time.

The next stage of this study is interviews; however, you do not need to participate in the interviews if you do not want to. If you would like to possibly be selected to partake in an interview, please contact the researcher with the subject: ‘Mini-Dissertation Interview’. You will be informed by the researcher if you have been selected to partake in an interview and possible time slots will be communicated to you as soon as possible.

Researcher’s contact information: christina.firkins@up.ac.za or u18169733@tuks.co.za.

Appendix II

Interview schedule

Interview Questions

Main question: Can you tell me about your process when selecting music for your ensemble?

What inspires you when it comes to repertoire selection?

What would you consider the most important aspects throughout the process?

While searching and selecting music to include in your repertoire, what are some of the challenges you face?

How have your experiences shaped and changed how you select repertoire?

What would you consider great advice for new conductors when it comes to repertoire selection?