Information Research

Special Issue: Proceedings of the 15th ISIC - The Information Behaviour Conference, Aalborg, Denmark, August 26-29, 2024

An information behaviour exploration of personal and family information and curation of our life histories

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir292839

Abstract

Introduction. Family stories and life histories are often shared among household and family members via oral and written communication, family traditions, and many other information practices. We explore these practices through the lens of information behaviour.

Method. This study uses first-hand reports of such family information practices. We use collaborative autoethnography through a narrative methodology for creating rich understandings of information practices within families.

Analysis. The first-hand self-reports from the four authors/researchers from four different countries are analysed using a narrative analysis method.

Results. Although each author describes the process of gathering and preserving their personal and family history differently, they all consciously or unconsciously defaulted to the role of information holders and occasionally gatekeepers of personal information within their families, especially as the previous generation age, suffer memory loss, or pass away.

Conclusion. Family events such as holidays, celebrations, funerals, and other spaces in which members come together, serve as boundaries of our information worlds, or as information grounds. However, the tension between traditional and digital documentation and communication methods within families, the digital divide, and globally dispersed families can lead to intergenerational information loss.

Introduction

Why is an exploration of family information and the curation of life histories important? Families do not simply persist. People spend time and energy to maintain them (McKenzie, 2021). Families are complex, constantly evolving (McKenzie, 2021). Families can provide members with a sense of meaning, belonging, and identity, but they can also be a source of conflict and sadness. Learning about our own forebears’ lives and life histories can help us locate our place in the world, where we have come from and where we are going. Thus, family information plays an epistemic role and contributes to our knowing of ourselves, and to understanding aspects of our culture, social custom and more. In this paper we examine the role of family information in our life histories, how we come to understand them, and how future generations may have a different experience in developing that understanding. Some labour required to manage and curate one’s family history can be pleasurable, or even a leisure activity, while others are a daunting job, often left to genealogists and family historians, but not all of us have that luxury.

In this exploratory paper, we use collaborative autoethnography and a narrative method for creating a rich and holistic understanding of information engagements and practices within families, based on information-sharing between four information researchers from different countries, each one drawing also on their rich research experience. The paper will contribute to our understanding of family information practices through a lens of human information behaviour theories, outside of the technological focus of traditional studies on personal information management, data management, or records management, and reflect on the long-term implications for families. Although there is some literature on family information practices (McKenzie, 2021), there is currently no theoretical framework that can specifically be applied to family information behaviours with respect to family histories.

The overarching research question for this study is: What information behaviours do we engage in within families in regard to family histories and family information. Specifically:

How do family members share, collect, and preserve their own life histories?

What are the impacts of aging and the digital divide on family information?

What specific information behaviours do family members engage in during the process of collecting and preserving family information?

Related work

Information is required to provide understanding and meaning for our family and our life more broadly. The field of personal information management (PIM) refers both to the practice, and the study of the activities people perform to manage personal information in all its formats and for all of a person’s roles, responsibilities, and interests. There is an emphasis in PIM on the organisation and maintenance of personal information collections, which are stored for later use and reuse (Jones et al., 2017). However, there is limited PIM research on collective family practices within private household settings and their effect on personal (and family) information management.

PIM is related to the field of personal archiving, which explores storage of personal documents through one’s life, and at least in the (professional) collecting archivists’ view, focuses on long-term heritage of personal information of value to society, or 'evidence of us' (McKemmish, 1996). Personal archives are also collected by people in their personal capacity, and in McKemmish’s terms capture 'evidence of me'. For most people such a collection has meaning, and they collect, store, and share such evidence of themselves, but others do not. The functionality of such a collection can be dependent on how systematically we go about capturing and managing records that can evidence and memorialise a life.

In exploring and understanding family information and life histories there is some emphasis in the literature on information that can be documented, found, organised, stored, and managed, but in practice, family information and life histories also include information that is embodied in family practices that can only be construed relationally (McKenzie, 2021). In other words, these are relational practices, or a set of actions, behaviours, or activities that involve and emphasise the quality of relationships between individuals or within and across families, for 'each of us has the experience of being a person set off in some way from other people and the rest of the world' (Gorichanaz, 2019, p.1352). This experience starts within our families. While some of that information can be documented, collected, and maintained, including the non-institutional documents of everyday life (McKenzie and Davies, 2021), not all can be stored in systems beyond the system that is the person.

Some of this information is stored and internalised in our memory (Krikelas, 1983), only to be elicited or instantiated through certain events, objects, or tactile interactions (Zijlema, 2018; Zijlema et al., 2019). Bates (2002, p. 4) proposed that we absorb perhaps 80% of all our knowledge through 'simply being aware, being conscious and sentient in our social context and physical environment'. We posit that memory, and this awareness are particularly relevant for family information and life histories. Memories that comprise family information and life histories (that include material culture such as objects and artefacts) are often passed down from elder to younger generations, but these memories can only really be communicated through narratives from one family member to another.

As people age there may be a decrease in physical well-being and cognitive functions, encompassing memory decline (Cole and Balasubramanian, 1993; Williamson and Asla, 2009). Williamson and Asla (2009) use the phrase 'oldest old' to describe a 'fourth age' during which increasing illness and dependence make a marked difference in life, including in people’s information behaviours. They suggest that the most outstanding sources of everyday life information for older people are family members and friends. We posit that these elders are also an outstanding source of family information that can contribute to following generations’ life histories.

Such family information may be shared informally in settings such as family gatherings, weddings, funerals, and other celebrations where people come together in a space/place and share information, creating dynamic and temporal information grounds (McKie, 2018). These information grounds also have affective dimensions such as joy, sadness, trauma, and grief, based on the occasion. Increasingly, such family information is also shared on social media and family group chats (Resor, 2021).

Methodology

The paper uses collaborative autoethnography and a narrative methodology (Ford, 2020) to create rich understandings of information engagements and practices within families, based on information-sharing between four information researchers, each one drawing on their rich research experience, thus eliciting the theoretical power of stories (Mitchell and Egudo, 2003). Such rigorous autoethnography is not the same as an autobiography (Gorichanaz, 2021. We collaboratively examined family information practices, information gatekeeping, and information encountering, drawing on our narratives, reflections, and observations, fostering a co-constructed understanding of our topic of interest.

There is a growing recognition of such narrative approaches to information research, encouraging information researchers 'to surface their subjectivities and give voice not only to their users or participants but to themselves. Each scholar has a unique story to tell the Information Science field and profession' (CAIS, 2013). Fourie (2021) showcases some of the different types of autoethnography used in library and information science, including Gorichanaz (2021, p. 85) who states that 'Each of us has a perspective on the world, and it is part of the goal of autoethnographic research to illuminate and communicate that perspective [rather than see autoethnography as] researcher bias.' Such accusations of bias can come from the assumption that autoethnographies come from a privileged perspective; however, this can also be seen as expertise and experience.

Anderson and Fourie (2015) state that 'Storying our research in this fashion has the power to teach us because in the very crafting of such stories we are compelled to take an interest in the concrete.'

One of the critiques of autoethnography is that it reveals information about others who may not have consented nor be able to consent (Lapadatt, 2017). To address this issue, we operationalised the concept of relational ethics, with its four underlying principles: mutual respect, relational engagement, bringing knowledge back to life, and creating an environment for rigour and responsibility to the people who are part of the stories we tell about our own experiences or the ‘identifiable others’ (Ellis, 2007). The four researchers, who were independently reflecting on their family histories and recent family developments, met in person at a conference, found convergences in their stories, decided to ideate the study in group meeting, then wrote their individual narratives, and met frequently online to agree upon the direction and thrust of the research. We read each other's narratives and analysed them into emergent themes that were meaningful to all of us. This is also known as a concurrent collaboration (Chang et al., 2017). An advantage of such collaborative autoethnography is to broaden the gaze from the lonely traumas of the self to locate them within categories of experience shared by many, thus expanding the research scope beyond personal situations (Lapadatt, 2017).

Narrative data

Researcher 1: India

Spoken History

Once a year, on the death anniversary of the most recently deceased elder of the family, my extended family gather around a ritual fire pit, and learn, recite, and sing the names of every family member going back about five generations. This information is not written down within the family but is only passed on orally and aurally every year, from generation to generation, and only on this one day, once a year. I always thought that this genealogy was just some family myth, and yet, I have recently discovered that this true genealogical record can be found in a written form, and is up to date, at one location, thousands of miles away.

Documenting family

An elder from every generation in most Indian families makes a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Haridwar, often after they retire, to record the details of their family. It’s often called a pilgrimage, but now I’ve discovered that in reality, it is a genealogy trip. When a person walks around this city, s/he is approached by 'information brokers' who want to know if you are looking for your family’s 'genealogy register'; there are more than thousands of such information brokers just in this small pilgrimage town, and each one of them carries the 'index' of states, regions, and villages – the metadata – in their head. Once they have triangulated the information you provide, they direct you to one of the pundits or pandas, who holds your family genealogy among thousands of others; there are 45,000 such pundits in this town, operating out of their homes.

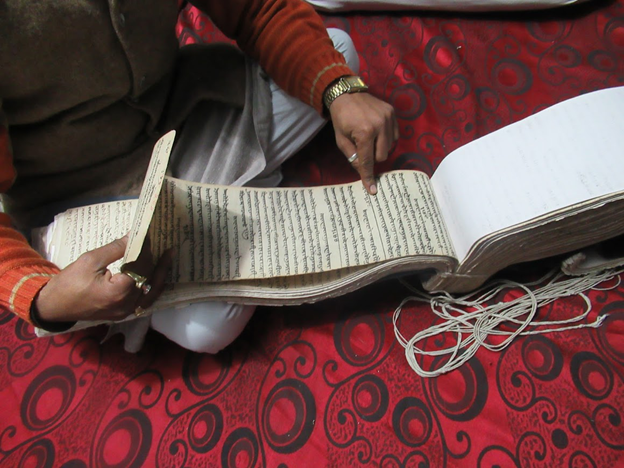

Once family name, clan name, and ancestral village names are confirmed, the pundit unlocks a locked steel vault and retrieves a rolled-up, bound, document scroll or vahi (a genealogy register), written on archival paper with Indigo ink (figure 1). The reason for their existence has to do with the Indian belief that the family is everlasting and comprehensive and that each person must look out for their ancestors and perform annual ceremonies for their journey to nirvana. A visitor cannot alter any of the existing records (thus maintaining their integrity), and one is also required to state one’s place within this family and extend the records with new accounts of births, deaths, and marriages; people often come to this town to inter the ashes of a family member in the river Ganges before adding to the record. The pundit writes it all down and then asks you to sign it. He then gives you a bag of sweets to take home to your family and puts a plate out for a 'mandatory' donation.

Since the 1990s these documents have been granted legal document status in India and are even admissible in court in family disputes (Kundalia, 2015). Some records go back to 1194 AD, with the older ones on palm leaf, although they are rapidly being lost to the vagaries of time. Some of these records have been microfilmed and are now part of the Granite Mountain Records Vault in the US, owned by the Mormon Church, but the very process of this digitisation is now a highly controversial matter for the pundits who provided the records for digitisation but now have no access to the records themselves. In a country often called the 'Document Raj' (Raman, 2012) due to its obsession with record-keeping, documenting these living archives has a high relevance to Indians in India and the Indian diaspora.

Reflection

I am my family's archivist and have diligently preserved photo albums and other documents over the years, although it has become an overwhelming task in the digital age. However, I have recently come to question their value, as I reflect on the use/uselessness of all this collected information as I increasingly encounter dementia in the family, with several elders and knowledge holders slowly losing their memories. These are people who have lived full lives and have accumulated so much valuable information and memories. None of it is relevant to them anymore. However, they have flashes of memory and clarity only when they handle certain objects, artefacts, or hard copy photo albums with their hands. They cannot understand a thing posted on the family WhatsApp groups either, as they cannot focus on a digital screen anymore. On the other hand, my mother has written a daily diary for over 60 years now (and continues to write daily) and these documents sit in her cupboard and may yet become my only information source for a lot of questions I may have about my family later. If only I could sift through those many daily diaries without an index!

Figure 1. Image of a Panda in Haridwar, India, looking up the family genealogy register (photo by Researcher 1)

Researcher 2: The Netherlands

Spoken history

My earliest memories of family gatherings are the annual celebrations of my grandmother’s birthday, where the extended family came together in a rented hall of the local church. At that time, about 70 family members on average would attend. Besides the usual catching up, laughter, reminiscing, introductions of new partners, birthday songs, and gift giving, my grandmother had started a somewhat peculiar tradition. She would bring presents, mostly handmade by herself such as crocheted pillows and coasters (figure 2), and every member of the family was expected to choose one to take home. While we appreciated the effort and the kind gesture, the crocheted coasters and other knick-knacks were accumulating in drawers and cupboards over the years, unable to be discarded due to sentimental reasons.

Another tradition in the family allowing for reminiscing and memory making are the bi-annual family weekends. On these weekends, my extended family, who live in all corners of the country, come together and stay in a self-catered group accommodation. We play board games, undertake sport and cultural activities, perform sketches, chat and laugh. Youngsters may build a bonfire if the surroundings allow this, and some family members may bring slideshows or videos of earlier family events. These slideshows and videos (without sound) would be impossible for me to understand without the accompanying narration of the older family members, as many of these records are older than me. Records such as photos taken are nowadays shared in a family Whatsapp group.

Documenting family

Dutch genealogy records are stored at city archives, and our family tree was developed to some extent by a diligent cousin. My paternal grandmother’s offspring grew to over 100 family members, including partners and great-grandchildren. The family members lived in different parts of the country, and some even (including myself) in other parts of the world. In 1996 the first edition of a family magazine was published, filled with stories and photos from family members. Contents included anecdotes and photos from a long time ago, sharing recent (individual) experiences or events, introductions from (new) partners, or children introducing themselves and their daily lives. After our grandmother passed away at the age of 104, some transcripts of her personal diary were published as well.

Reflection

It is a privilege to have access to family stories, and to have several of them well documented. I also consider it a privilege of being able to meet or have met nearly all family members of my parents’ generation. The family magazine is the strongest piece of documentation we have in terms of family information, but takes time and effort, and depends on the contributions by family members. It was decided last year to stop producing the magazine after 27 years. A family WhatsApp group is occasionally used, though does not include all members of the family.

My parents, uncles and aunts have so far invested the most in sharing and documenting information with the rest of the family, and I consider them as the archivists and gatekeepers of personal family information. The investment by the subsequent generations is less, though may be stronger at times on an individual family level. This creates information gaps in the family (history) sharing and documentation.

Regarding my personal practice, despite my research involvement in information management and personal possessions, it is not as organised as I wished it to be. Having lived in different countries in the past 10 years without having fully settled, means that my information management of family history is scattered, and the above-mentioned documentation is mostly stored at different locations (boxes, shelves etc.) in my parents’ home. Living far away for some time also meant I was not able to attend family weekends, to allow for informal cuing of memories and building memories together.

Figure 2. Researcher 2’s memento from their grandmother’s annual family gathering

Researcher 3: Cuban-American

Spoken history

As the daughter of Cuban exiles, there was a great deal of difficulty obtaining family stories from my elders. My parents and grandparents left everything behind and brought only the shirts on their backs. There was no starting point for me to draw from. Finding information about my family's past led to conversations with my family members themselves. They may have had it all in what was a pre-communist Cuba, but when they left their homes for a better life in the United States, they had nothing left but their hopes and dreams for a better life and for better stories to tell. As I reflect on my family's immigration situation, and our family's archives, consisting of photographs, stories, and memories, it has always been a sensitive issue. I have had resistance when asking my family what their life was like before arriving in the United States. I discovered that the majority of my family's stories were learned through special occasions such as birthdays, holidays, and deaths where the family found time to gather and share how things were and how things are now. I have come to realise that the sharing of family stories that occurred under traumatic circumstances will remain in silence but never forgotten.

Documenting family

There was never an incident, and there was no time I could recall, that one spoke freely of what happened back in my family's homeland unless it was based on a current experience. Most of the difficult stories were from my grandparents, they did not have a filter or a need to alter their life. I discovered that my parents were more sensitive to sharing stories, and oftentimes had difficulty finding the words to describe what they could remember. I found that my parents’ stories were partial, and only highlighted gleeful moments from childhood, while others relished in the flavors of the cuisine and flavors they longed for. My grandparents' stories were of necessity, desperation, and nostalgia. The nostalgic stories recounted a time when worries were centered on making it in time for work, attending parties, and planning family gatherings. The stories of desperation and necessity came out of the uncertainty they experienced upon losing jobs, experiencing the loss of resources, and overall food scarcity. I was constantly reminded how fortunate I am, and how they may have had the same opportunities if the Cuban Government had escaped a communist regime.

As I set the stage for sharing how my family processed their memories, I can still hear bursts of laughter at funerals, where you would think only sad stories would emerge, but from my experience, funerals allowed for the family to find the funny, and ridiculous moments they had with the departed, and that is where I truly got to know who I was mourning. So many stories, that remained hidden away, like one of my uncles who as a child ate the center of every freshly baked Cuban bread, and left the outside shell, as an illusion for my grandmother to find at dinner time. I learned of infidelities, friendships, and even familiar grudges in this way too. My family spent countless hours storytelling over games of Cuban Dominoes (figure 3). At family birthdays, we heard birth stories, typical of the ones that start with the day you were born. This is how I found out about my own birth story as I approached my later teenage years.

Family gatherings were my closest companion to these stories, the sound of their voices, and how they pronounced and sang their favorite songs. Dancing and storytelling were one of the ways my maternal grandmother re-lived her youthful days in Havana. I can still imagine her if she were alive today, with one hand up and one hand cupping the air as if she had a dance partner, showing the movements of the dances she knew. As she spoke of all the beautiful celebrations she had attended, through these moments, I also saw my grandmother, full of life, showing her love for her culture, music, and dance styles that I now wish to learn, like the famous Cuban Danzón. Listening to music at family gatherings also allowed stories to emerge, the dancing brought the stories, made them feel as if they were happening in the moment, and the memories were not as difficult to share.

Reflection

I began to think of how I process my memories having not lived in the circumstances my family had experienced. I can relate to the stories of nostalgia, but I can never see what my family’s homeland once was because little was left of it. This made me realise why my parents may speak little of their past for this same reason. I also associate their age difference, one clearly remembers growing up in a Cuba that was attempting to reemerge at the start of the revolution while the other, the regime is all they knew.

I can understand the avoidance of telling these stories, and how this may affect the process of remembering. I appreciate their loss and understand that it is much easier to avoid than to remember and mourn, for the loss of what it used to be, can lead to repressing these memories.

By avoiding the past, I cannot learn the true stories behind how my family survived living through those difficult moments. For how can anyone process their familiar histories beyond the happy moments, when those moments of difficulty and despair are what showed the tenacity, the character, and the will to survive? I want to know their stories, no matter how difficult they may be. I want to live them through my dreams, as I collect my personal histories, my family will be but a reflection of my own, but difficult to comprehend if only the good times were told. What can this teach us, as we dive into the past, and prepare to tell our stories to our children?

Figure 3. Researcher 3’s Dominoes tiles, along with two silver coins that are currency from Cuba. The coins are dated 1961, a time when both my paternal and maternal families were still living on the island. The coins read, 'Patria y Libertad', Spanish for homeland and freedom. The heart locket in the middle belonged to the researcher’s paternal grandmother and houses a photo of when the researcher was 5 years old.

Researcher 4: Descendant of immigrant Australians

Spoken history

Both my parents, and the two grandparents I knew, were great family story tellers. Both born and bred in Adelaide, South Australia, by the time I was born, my nuclear family traveled extensively and lived in many locations for my father’s work. In those days it was difficult and expensive to travel, but despite this every year we traveled to my parent’s birthplace and spent an extended Christmas period with our extended families. Stories were told, children played, food was eaten, photographs in slide shows enjoyed or endured depending on one's age and interest, and love generated and nurtured. Raucous but friendly arguments were had about the 'real' interpretation of events and the other components of family histories, and such storytelling often ended with, 'we’ll have to agree to disagree on the finer details of that!' So we grew to know the general background of where we came from, who we were, and about our families' shared and unshared values.

Documenting family

Although a great raconteur my father was also very systematic and wrote a daily diary, which in his (all too short) retirement he drafted into a memoir. It contains a family tree accurate until the time he died, and a summary of the family history which he had been researching in various archives and other places throughout his life. My mother’s uncle was the family historian on her side of the family, and he gifted my father family trees, written histories, and shared family stories on our rare visits to him, the bones of which were incorporated into dad’s memoir. It was never completed, and I have neglectfully been holding onto the draft, which I have been meaning to type up for my family. But I did read it as it was being written and discussed it with my father. One criticism I had was that after the brief family information it was too much about his work (meaning perhaps there was not enough about me or the family in it), but he said we all had to tell our own stories, and that was his.

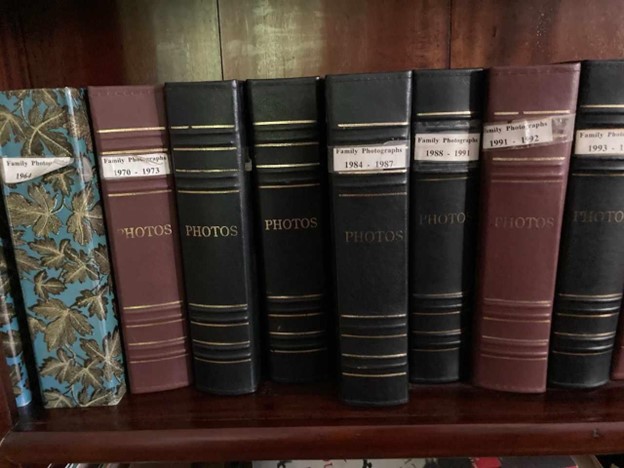

Another thing my parents did was compile family photographs into albums (figure 4), which as they have now both died are in my care as the eldest child. They are beautiful and sit on my shelves, and I raid them (as have others) for family gatherings and funerals, and occasionally browse through them and find joy in memory there when I need it. These albums, and current photographs were used to create a book for my mother who slowly developed dementia. As her illness progressed these photographs of her loved ones provided prompts for stories, about what her children and grandchildren were up to, and about what happened in her past with her parents, siblings and extended families. As dementia made conversation harder the photographs provided conversation and story starters and enabled a sense of connection for us with her past and for her into the present, long into her illness.

Reflection

Extended family gatherings are now less common, as members of the extended family have dispersed around Australia and the world, rather than just one small part of it. Despite the relative ease of travel, arranging everyone to be in one place at the same time becomes more and more difficult. For a time, news, memories, and stories were shared via Facebook and Instagram, but those venues, and such sharing, are now out of favour with the younger generation. Even if they were still widely used the algorithms behind what is displayed and retained remain opaque and changeable - unreliable. If I die tomorrow, I leave to my children only the family history leading up until my father’s death, as it is all his work.

Alas, despite being a librarian by education, I have not inherited the discipline of documentation from previous generations. I have no diaries. Because of an issue with my eyes, I was unable to take photographs until the invention of the smartphone. Mine now contains thousands of unsorted and unlabelled photographs. The original archives contributing to my father’s memoir were left with my mother. Before we were aware of the extent of her dementia, she had begun cleaning up - in her words, 'to spare us' having to do it when she died. Those wonderful old rolled up family trees I remember, the old passports and vaccination certificates, the letters, everything, were gone before they could be rescued. Would I have had, do I have, the discipline to document, and if I do, would my children and their children, would anyone be interested in this changing world?

Figure 4. Image of Researcher 4’s shelves of family albums.

Analysis of narrative data

In this multi-voiced narrative, we took an evocative approach to autoethnography, which often begins with the researcher’s lived experience. Although we started by writing down the process of understanding our family stories from our own perspectives, we read it together again and again with the knowledge that others would also read it, and hoped they would understand it the same way we understood each other’s narratives. All of the original narratives were much longer than presented summarised for this paper.

Although our narratives come from very different countries and cultures, each of our narratives present our authentic voice. They have rigour as described by Gorichanaz (2021) as '... the generalisability of a given study rests on the detail in which the setting and methods are described. Autoethnography, as a narrative form of research, is concerned with naturalistic or story-based generalisability...' (p. 83). This is different to generalisability in statistical research which applies findings to specific populations, or in case-based research which applies it through case-based reasoning.

All authors describe family gatherings as one of the main spaces where personal and family information was shared, exchanged, or passed on. Author 1 talks about how generations of oral transmission had preserved their family history in India, but in the digital age, with the global dispersal of family members, a lot of the family history was fast disappearing, without it being replaced by any digital technology that was equally effective. Memory loss of the elders in the family due to dementia has also contributed to this. Author 2 describes their family tradition in the Netherlands of documenting family history through handwritten and printed articles. Once again, due to ageing and the tendency to use faster and shorter communication technologies, this tradition is fast becoming endangered with the risk of information loss. Author 3 describes the specific and unique issues faced by their Cuban American migrant family who have experienced family trauma and hence intentionally or unintentionally lost family history. Author 4 from Australia describes the loss of much-valued family memories, documents and artefacts due to a family member’s dementia.

Although each author describes the process of gathering and preserving their personal and family history differently, as researchers and scholars in information, each of us had consciously or unconsciously defaulted to the role of information holders and sometimes even gatekeepers (Barzilai-Nahon, 2009) of personal information within our families, especially as the previous generation are ageing, suffering memory loss, or passing away.

In reading all four narratives, we also have some discernible similarities that run through all of them, especially in the way that family information is communicated within families and also from one generation to the next.

In all four narratives, family gatherings, big or small, become sites of interest. However, there is a difference between the temporary 'spaces' that bring large families together and the more familiar and particular 'places' (Tuan, 2001) of our smaller family interactions which give meaning to our spaces.

Conceptual information worlds and boundary spaces

All of us exist within our own 'small worlds' such as close friends, immediate family, colleagues, and people with shared interests (Chatman, 1991). Burnett (2015) extends this concept of Chatman’s 'small worlds' into a Theory of Information Worlds wherein he adds and expands the concept of 'boundaries' to Chatman’s core ideas of social norms, social types, worldview, and information behaviour. '”Boundaries” [are] the places at which different worlds come into contact with each other in one way or another […] [with] […] different kinds of information [and] different value[s] attached to [that] information' (Burnett, 2015, p. 9). These can be physical, metaphorical, or conceptual spaces. In some ways, these boundaries can be spaces outside of our 'information horizons' (Sonnenwald, 1999), the regular spaces within which our information normally comes from. Within all four narratives in our study, family gatherings (be they physical, virtual, or epistolary spaces), served as boundaries where several nuclear families from within a larger family/clan met once or twice a year. All four researchers learned some new information about their own and their extended families at these boundary spaces, where different 'small worlds' come into contact, leading to serendipitous information encountering (Foster and Ford, 2003), learning, identity negotiation, and even promoted a sense of belonging.

Information grounds or place-based interactions

In all four narratives there is a fine distinction between the boundary spaces of our Information Worlds (as described above) and what is better known as information grounds or '…an environment temporarily created by the behavior of people who have come together to perform a given task, but from which emerges a social atmosphere that fosters the spontaneous and serendipitous sharing of information' (Pettigrew, 1991, p. 811). They also described smaller family gatherings within nuclear families where oral histories were shared informally over a family meal or a drink by the fireside, which can be considered temporal information grounds. Such oral practices can serve as valuable sources of family history when approached with a rigorous methodological framework (Vansina, 1985). These place-based interactions are now also online on family social media, for the cyberspace becomes a cyberplace wherein these platforms enable temporary virtual spaces, or ‘foster temporary settings that enable information grounds, which can be accessed anytime, anywhere, and is not restricted to a certain number of participants’ (Talip and Yin, 2017, p. 1).

Information avoidance

Case et al. (2005) described information avoidance as a stress and coping mechanism when we face traumatic memories in our lives. Narayan et al. (2011) expanded the theory of information avoidance to describe two kinds of information avoidance: active information avoidance (that is often short term) and passive information avoidance (that can be long term).

Such information avoidance is observed in all four family narratives to some extent but is most profound in Researcher 3’s family history narrative where elder family members avoid sharing information that still causes them trauma. Others avoid information due to information overload, task overload, or losing interest and/or connections due to the digital divide between generations and also the increasing geographic dispersal of families.

Family documentation and memory

Our narratives describe families that hold some form of documentation of family history through daily diaries, letters, genealogy records, photographs, or objects and artefacts. However, their meaning was often transmitted orally.

Objects and artifacts, along with documents can be cues to family memories and stories, as has been described in several research studies (Narayan, 2015; Petrelli et al., 2009; Petrelli and Whittaker, 2010; Zijlema, 2018). Authors 1 and 4 both described that archived photos were used to aid conversations with their elders developing dementia. Author 2 described the crocheted coasters and other handmade objects that were passed on as a gift and still evoke memories, as they are imbued with stories. Author 4 shared treasured objects that invoked family stories.

We learn through all four narratives that the majority of the family archives are being maintained physically, emotionally, and orally. This presents the challenge of their sustainability. We mentioned that family archives are kept alive through stories, memories, and participation in family gatherings. Family Archives' existence is often influenced by the aging family members who are gatekeepers to family history and rely upon the one family member who can salvage these stories. Many families do not have any succession planning when it comes to family history. Family archiving should happen collectively and should be recorded not just by spoken word, but in a space that can be retrieved by future generations, an information space possibly consisting of recordings, files and documents recorded digitally and saved in a storage system for future use.

Discussion and conclusion

Family events such as holidays, celebrations, funerals, and other spaces in which members come together, serve as information grounds (McKie, 2018; Pettigrew, 1999;), with opportunities to document, rehearse, and reflect on personal and family stories, or share new information about current personal or family affairs, strengthening the family bond and identity. There are opportunities for future research to look at such family practices through the framework of information grounds, which could be termed family information grounds.

Both physical and digital mementos are an essential part of family information (Petrelli and Whittaker, 2010). However, the tension between the traditional methods of documentation within families and the lack of uniform access to the new ways of communication leads to intergenerational information loss. The elders of families curate their memories and documents, family information and life histories for themselves and subsequent generations. As their memory and other abilities decline, aspects of younger generations’ life histories can also be lost, before they have time, or perhaps even the interest, to curate their own life memories for themselves. In terms of implications for the library profession, there is an opportunity here to provide the training, means, and resources (such as media rooms) for families to curate their own family histories and also share with the community if they wish.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank their immediate and extended family members for sharing family stories, and for showing us ways of memory-keeping with us throughout our lifetime. The authors dedicate this paper to each other and to our respective families for listening, sharing, and reflecting on family.

About the authors

Dr. Bhuva Narayan is Associate Professor of Communication, and Director of Graduate Research at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS). Her research interests include Human Learning, Health Information Behaviours, Information Avoidance, Digital Literacies, Personal Information Management, Scholarly Communication and Open Access. She is associate editor of the Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association (JALIA). E-mail: Bhuva.Narayan@uts.edu.au

Dr. Annemarie Zijlema is a Lecturer at the School of Computing and Mathematical Sciences at the University of Greenwich. Her research involves Human-Computer Interaction and information behaviours, and she has a strong interest in cognitive processes in relation to external cues, such as objects in the home, information on our personal devices, public spaces, or information on the web. E-mail: annemarie.zijlema@greenwich.ac.uk

Dr. Vanessa Reyes is an Assistant Professor in the East Carolina University Library Science Program. Her research explores the field of personal information management (PIM), and personal and community archiving. Her studies focus on how users organize, manage, and preserve digital information, contributing to digital heritage preservation. Her research also addresses the need for personal information tools that support users as they age. E-mail: reyesv23@ecu.edu

Dr. Mary Anne Kennan is a retired academic, whose last role was as Associate Professor at Charles Sturt University. She continues as a researcher and her research interests continue to focus broadly on scholarly communication including open access and research data management; education of, and roles for, librarians and information professionals; and the practices of information sharing and collaboration in various contexts. She is editor of the Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association (JALIA). E-mail: mkennan@csu.edu.au

References

Anderson, T. D & Fourie, I. (2015). Collaborative autoethnography as a way of seeing the experience of care giving as an information practice. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014: Part 2, (paper isic33). Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/20-1/isic2/isic33.html

Barzilai‐Nahon, K. (2009). Gatekeeping: A critical review. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 43(1), 1-79. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2009.1440430117

Bates, M. J. (2002). Toward an integrated model of information seeking and searching. New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 3, 1-15.

Burnett, G. (2015). Information worlds and interpretive practices: Toward an integration of domains. Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 3(3), 6-16. https://doi.org/10.1633/JISTaP.2015.3.3.1

CAIS (2013). Tales from the edge: narrative voices in information research and practice, http://www.diigubc.ca/cais-acsi/en

Case, D.O., Andrews, J.E., Johnson, J.D., & Allard, S.L. (2005). Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. Journal of the Medical Library Association. Jul. 93 (3): 353–62.

Chatman, E. A. (1991). Life in a small world: Applicability of gratification theory to information-seeking behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(6), 438-449. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199107)42:6<438::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-B

Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F., & Hernandez, K. A. C. (2016). Collaborative Autoethnography. Routledge.

Cole, C. A., & Balasubramanian, S. K. (1993). Age differences in consumers' search for information: Public policy implications. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 157-169. https://doi.org/10.1086/209341

Ellis, C. (2007). Telling secrets, revealing lives: Relational ethics in research with intimate others. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(1), 3-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800406294947

Ford, E. (2020). Tell Me Your Story: Narrative Inquiry in LIS Research. College & Research Libraries, 81(2), 235-247. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.81.2.235

Foster, A., & Ford, N. (2003). Serendipity and information seeking: an empirical study. Journal of Documentation, 59(3), 321-340. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310472518

Fourie, I. (Ed.). (2021). Autoethnography for Librarians and Information Scientists (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/10.4324/9781003014775

Gorichanaz, T. (2019). Conceptualizing self-documentation. Online Information Review, 43(7), 1352-1361. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-04-2018-0129

Gorichanaz, T. (2021). “How does this Move us Forward?”: A question of rigour in autoethnography. In I. Fourie (Ed.), Autoethnography for Librarians and Information Scientists (pp. 79-91). Routledge.

Jones, W., Dinneen, J.D., Capra, R., Diekema, A., & Pérez-Quiñones, M. (2017). Personal information management. In J.D. McDonald,, & M. Levine-Clark (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information science (pp. 3584-3605), fourth edition. CRC Press.

https://doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS4

Krikelas, J. (1983). Information-seeking behavior: Patterns and concepts. Drexel Library Quarterly, 19(2), 5-20.

Kundalia, N.D. (2015). The Lost Generation: Chronicling India’s Dying Professions. New Delhi: Random House India.

Lapadat, J. C. (2017). Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qualitative inquiry, 23(8), 589-603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417704462

McKemmish, S. (1996). Evidence of me. The Australian Library Journal, 45(3), 174-187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049670.1996.10755757.

McKenzie, P. J., & Davies, E. (2021). Documentary tasks in the context of everyday life. Library Trends, 69(3), 492-519. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2021.0001.

McKenzie, P. J. (2021). Keeping Track of Family: Family Practices and Information Practices. Library Trends, 70(2), 78-104. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2021.0016.

McKie, I. A. S. (2018). Navigating mixedness: The information behaviours and experiences of biracial youth in Australia. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 10(2), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v10i2.5941

Mitchell, M. C., & Egudo, M. (2003). A Review of Narrative Methodology (No. DSTO-GD-0385). Defence Science and Technology Organization Edinburgh (Australia) Land Operations Div. https://www.webpages.uidaho.edu/css506/506%20Readings/Review%20of%20Narritive%20Methodology%20Australian%20Gov.pdf

Narayan, B. (2015). Chasing the Antelopes: A Personal Reflection. Proceedings from the Document Academy, 2(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.35492/docam/2/1/19

Narayan, B., Case, D. O., & Edwards, S. L. (2011). The role of information avoidance in everyday‐life information behaviors. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 48(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.2011.14504801085

Petrelli, D., & Whittaker, S. (2010). Family memories in the home: contrasting physical and digital mementos. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 14 (2), 153-169. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-009-0279-7

Petrelli, D., Van den Hoven, E., & Whittaker, S. (2009, April). Making history: intentional capture of future memories. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1723-1732. https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518966

Pettigrew, K.E. (1999). ‘Waiting for chiropody: contextual results from an ethnographic study of the information behaviour among attendees at community clinics’. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 801-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4573(99)00027-8

Raman, B. (2012). Document Raj. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Resor, J. M. (2021). Family Processes in Family Group (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech). https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/items/2c48e1c0-c0fd-4572-a19f-234cf2b83d57

Sonnenwald, D.H. (1999). Evolving perspectives of human information behaviour: contexts, situations, social networks and information horizons. In T.D. Wilson & D. Allen (Eds.), Exploring the contexts of information behaviour. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Research in Information Needs, Seeking and Use in Different Contexts 13-15 August 1998, Sheffield, UK.

Talip, B. A., & Yin, D. B. M. (2017). A proposed model of online information grounds. In Proceedings of the 11th international conference on ubiquitous information management and communication, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3022227.3022246

Tuan, F.Y. (2001). Space and Place: A Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis.

Vansina, J. (1985). Oral Tradition as History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Williamson, K., & Asla, T. (2009). Information behavior of people in the fourth age: Implications for the conceptualization of information literacy. Library & Information Science Research, 31(2), 76-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2009.01.002

Zijlema, A.F. (2018). Personal Possessions as Cues for Autobiographical Remembering [PhD Thesis, University of Technology Sydney & Eindhoven University of Technology]. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://research.tue.nl/en/publications/personal-possessions-as-cues-for-autobiographical-remembering

Zijlema, A., Van den Hoven, E., & Eggen, B. (2019). A qualitative exploration of memory cuing by personal items in the home. Memory Studies, 12(4), 377-397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017709872