Information Research

Special Issue: Proceedings of the 15th ISIC - The Information Behaviour Conference, Aalborg, Denmark, August 26-29, 2024

Information practices in multi-professional work in urban planning

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir292847

Abstract

Introduction. This study investigates information practices to develop multi-professional work in the planning of healthy living environments in and around urban planning.

Method. A qualitative approach was used to study information practices in two city organisations in Finland. 16 professionals working in urban planning, urban planning, traffic, landscaping, promotion of well-being and environmental health and protection were interviewed in semi-structural interviews.

Analysis. Interview data was analysed with content analysis, focusing on the information practices in their organisational and multi-professional context.

Results. The professionals maintained and developed information practices to use, seek, share and create information in their work on urban planning within city organisations and in the stakeholder networks.

Conclusion. The complexity of information-based decision-making can be understood by understanding the wide range of information practices as using, seeking, sharing, and creating information in multi-professional work. In addition, it is important to note, that also organising and managing both information and information practices are needed in information-based decision-making.

Introduction

Planning urban environments is based on various kinds of information and includes complex information processes and practices in which many parties are involved. Information-based decision-making is deeply rooted in the planning practices of city organisations and is approached as evidence-based planning (Davoudi, 2006; Faludi and Waterhout, 2006). In the planning work, the interests of various stakeholders, such as citizens, construction firms, other businesses, and organisations, are considered (Eliasson, 2000; Faehnle et al., 2014; McGuirk, 2001). At the same time, the decisions of planning and developing living environments should be based on the most relevant scientific knowledge (Lowe et al., 2015). In integrating various perspectives into the urban planning process, the professionals working in the city organisations are in a key position (Lysgård and Cruickshank, 2013). Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how people's health and well-being are seamlessly linked to the structures of living environments. In general, the aim is to plan healthy urban environments to live in, the premises of what this means, as well as who should be involved in planning processes, are changing. As new knowledge on the impact of nature and diversity on wellbeing and health (Lowe et al., 2015; Nieuwenhuijsen, 2021) emerges, there is a need to develop information practices which promote the use of this knowledge in decision-making.

In this study, we examine information practices (Lloyd, 2010; McKenzie, 2003; Savolainen, 2007) in the informed decision-making connected to the role of environment in human health and wellbeing in urban planning in this new situation. Our perspective is multi-professional: We examine, how urban planners and other professionals working in the city organisation seek to develop healthy urban environments in multi-professional collaboration, and how we can understand the challenges and possibilities of this work with the concepts of information practice research. Our research questions are:

What kinds of information practices exist in and around urban planning in city organisations, related to the development of healthy urban environments?

What kinds of information practices are needed to develop multi-professional work in these organisations?

By viewing multi-professional work from the point of view of information practices in the city organisation, we can understand the limits and possibilities of making information-based decisions in organisations, as new information is to be taken into use. In information practice research, collaborative nature of working practices has been acknowledged (Bronstein and Solomon, 2021), but there is a need to further study the complex, interactive and changing ways of working in information rich environments (see e.g., Widén et al., 2014).

Theoretical background

Urban planning as knowledge-based work

In the urban planning processes, various stakeholders are involved in different phases of the planning work (Merikoski et al., 2022). Work is heavily information-based, and involves organising multi-professional information processes, to gain all needed information for the decision-making. Through these developments, the planning work has been loaded with various kinds of perspectives, and the role of urban planners as integrating actors negotiating and organising the information processes to enable information-based decision making has been emphasised (Jacobs et al., 2015). In recent decades, we have seen how urban planning is linked to many social, societal, health and well-being challenges (Faehnle et al., 2014). The information needed for urban development is multidisciplinary, and linking information related to climate change, for example, to urban planning is a challenge (Eliasson, 2000). The integration of health and well-being data into urban planning and development has also evolved, with new tools and technological solutions (Fonseca et al., 2000; von Richthofen, 2022). It has also been pointed out that the utilisation of multidisciplinary expertise within the city organisation plays an important role in the planning of cities that promote wellbeing. To solve complex challenges, there is a need to ask how decision-making structures and the parties involved could be reorganised so that the best possible information could be obtained to support decision-making (Inam, 2011).

There is also a small body of research covering information-based phenomena in urban planners’ work in the field of Library and Information Studies (LIS) (Afida et al 2017; Bennett, 2006; Elliot, 2001; Makri and Warwick, 2010; Serola, 2009). In Finland, Serola (2006, 2009) has examined task-based information seeking behaviour and information sources used in urban planners’ work. In this study, the complex nature of urban planning and various information needs are examined in the context of one city. Serola (2009) approaches this by identifying different work tasks and types of information needs, suggesting that urban planners have core work tasks, such as concrete planning work and making wider studies and reports, which are aided by supportive work tasks, such as leading work, seeking information on organisational news, helping colleagues, client service and updating one's own professional skills. In their work, urban planners used information gained from colleagues and experts, official documents, planning documents, reports, instructions and direct observation, using channels such as information networks, print media, people, group meetings, and direct observation (Serola, 2009).

Afida et al. (2017) examined information seeking behaviour of city planners in Malaysia when performing a certain complex work task and pointed out, how important it is to connect the study of the information use to the work tasks and contexts of professionals. The study also illustrated the importance of authorised information sources which compiled knowledge on complex issues (Afida et al., 2017). While this study is limited in its view on information seeking behaviour in a certain task, it offers means to understand seeking, collecting and compiling information to form a basis for decisions on complex issues in urban planning (Afida et al. 2017). Also related to urban planning, Makri and Warwick (2010) have examined postgraduate architectural design and urban design students focusing on electronic tools to support architectural work from an information behaviour perspective. Even though Makri and Warwick (2010) focus on micro level information use and examine only information seeking, their findings are relevant also for this study as they emphasise, that there is a need to foster information behaviour related to sharing and distributing information, to be able to cope with the complex tasks in that context.

As seen from the previous studies, there is also a need to understand urban planning processes more broadly, not only focusing on certain tasks or issues. Here, the shift from information behaviour research to the study of information practices is needed (see Savolainen, 2007).

Information practices approach

In knowledge-based work, where people act and make decisions based on information (Choo, 2006; Citroen, 2011) and operate in certain contexts, which form physical and virtual information environments (Taylor, 1991, see also Widén et al., 2014). When acting in these information environments people develop information practices that can support or prevent the use of information when striving to achieve certain tasks or goals (Savolainen, 2007). Information practices provide a view of understanding human actions with information from a contextual and social perspective (Talja and Hansen, 2006; Savolainen, 2007). Information practice research has developed from the critical evaluation of information behaviour research, to shift the focus from individuals to action. According to Savolainen (2007, p. 126):

within the discourse on information behavior, the “dealing with information” is primarily seen to be triggered by needs and motives, while the discourse on information practice accentuates the continuity and habitualization of activities affected and shaped by social and cultural factors. (Savolainen, 2007)

Information practices have been examined both in everyday contexts (Lloyd and Olsson, 2017, 2019; McKenzie, 2003; Savolainen, 2008) as well as to some extent also in the context of work (Pilerot and Limberg, 2011; Widén et al., 2014; Bronstein and Solomon, 2021).

Information practices are 'a set of socially and culturally established ways to identify, seek, use, and share the information available in various sources' (Savolainen, 2008, pp. 2–3). Hence, information practices include various sets of intertwined actions. Information use is a broad concept and can mean any kind of acting and interacting with information to achieve a certain goal (Savolainen, 2007. To understand information use from a social and practice-oriented point of view means, that information is used in terms of gap-bridging (Dervin, 1983, 1999; Dervin and Frenette, 2003; Savolainen and Kari, 2006) to overcome a problem, get things done and make informed decisions. Information seeking is a core concept explicating information practices more closely, referring to 'a conscious effort to acquire information in response to a need or gap in your knowledge' (Case and Given, 2016, p. 6). In addition, like information use, it is related to the idea of knowledge gaps, that need to be bridged to solve a situation. However, information seeking can be active but also passive, when information is not actively searched (McKenzie, 2003). Information sharing is an information practice which refers to the ways people share information with each other interactively. Information sharing is reciprocal, useful for both parties involved in sharing (Pilerot, 2012). In addition, in LIS, the phenomenon of information creation has been developed especially in recent years (see e.g. Huvila et al. 2020) and is not always visible in information practices descriptions (e.g. Savolainen, 2007). Information creation, then, occurs as information is used to produce new information in various forms (Gorichanaz, 2019). Information creation can be understood as social action unfolding as practices related to creation of informative content regardless of its format (Koh, 2013). Furthermore, information practices can involve activities such as management of information (Zhong et al., 2023; see also Widén et al., 2014). Hence, the conceptualisations of information practices develop with research, and the boundaries between different practices are often blurred (see e.g. Lloyd, 2010; Willson, 2022). It is therefore essential to examine how different practices overlap and function in relation to each other when people solve complex information-based problems (see e.g. Pilerot and Limberg, 2011). Here, the linkages to the concepts of Information Management and Knowledge Management studies are clear. However, in this study, the focus is on practices and e.g. the management of information is primarily understood as managing, organising and working with information.

Information practices in multi-professional work

Information practices always happen in a certain context and with a certain purpose. Information practices in organisational settings have their ground in the definitions of information practices outlined in previous chapter. However, using information in organisations has specific features (Widén et al., 2014). For example, information use in organisations can be specified as an organisational practice (Du, 2014). Information use in professional contexts is shaped by context-specific and interactive features impacting the practices substantially, and the complexity of the tasks in hand vary (Du, 2014). According to Du (2014, p. 1852): teamwork in the workplace distinguishes professional work from general information use as it 'introduces complex social and contextual factors into the process of information use.' Hence, the circumstances of work such as organisational structures, division of work, work tasks and different roles impact on the aims and possibilities of using information in work (Leckie et al., 1996; Li and Belkin, 2010). In information studies examining work-related information use, '(Work Tasks) are undertaken in situational settings in which diverse information interactions, including information seeking, evaluation, use, and sharing, are taking place.' (Du, 2014; p. 1850) In complex work tasks, the need for different information sources and different types of information increases (Byström and Järvelin, 1995; Byström and Kumpulainen, 2020).

Organisational context and knowledge-based work give specific emphasis on interaction and collaboration (Du, 2014). Nordsteien and Byström (2018) investigated new healthcare professionals engaging with professional information practices and information culture in their workplace. The information was mutually shared, and the newcomers were acknowledged for the knowledge they possess. Bronstein and Solomon (2021) have studied information practices of lawyers, paying attention to collaborative practices such as working with others, mentoring, attending meetings, and helping each other. Pilerot and Limberg (2011, pp. 327-328) have examined design scholars’ information sharing and note:

A consequence of the fact that information sharing is an activity that is intrinsically intertwined with a wider information practice is that it becomes impossible to study as a separate individual activity. The information practice can be described as a bundle of overlapping and interconnected activities, permeated with meaning and values, organized into nexuses consisting of tasks, doings and sayings. This bundle is rooted in the order which shapes and is shaped by the activities carried out.

This notion is important in understanding complex work tasks and problem-solving processes requiring multi-professional work (see also Willson, 2022). Information practices to foster collaboration in organisations can be formal or informal, as Willson (2022, p. 803) note: 'Information sharing can be a purposive, primary activity (e.g. colleagues arranging a meeting to discuss work) or the result of social interaction (e.g. colleagues eating in the lunchroom and sharing information in conversation).' In examining information practices of communities and in knowledge work, this notion is important, as places and possibilities for information sharing are needed to solve complex, multidisciplinary problems and create new knowledge and information (Mitchell et al., 2009; Widén et al., 2014).

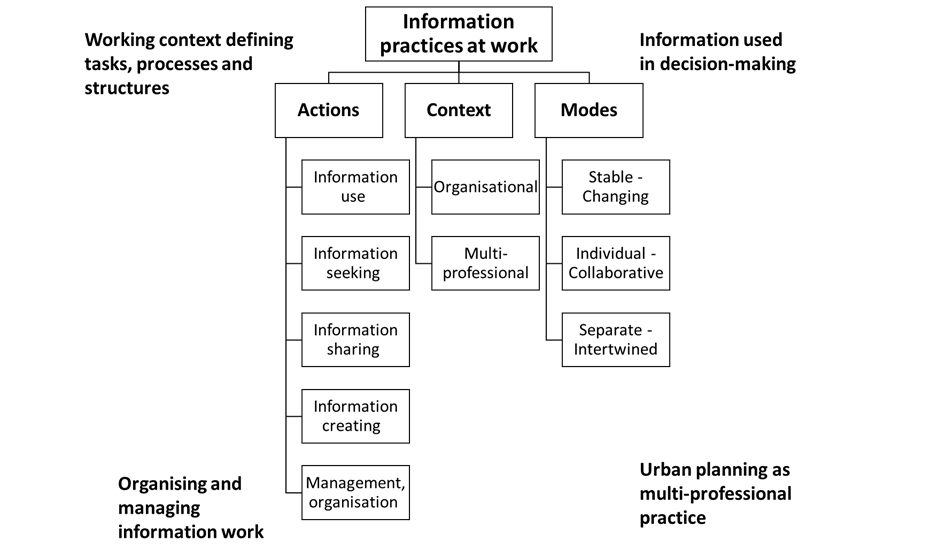

In this study, information practices are examined in their broad sense focusing on actions, context and modes of the practices, to shed light to the ways in which professionals maintain and develop information practices in multi-professional work. The frame of this study is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The frame of the study for the empirical examination of information practices in organisations.

Method and data

Based on the theoretical background and the aims of the study, we set to examine information practices in and around urban planning with qualitative approach. The study is based on semi-structured interviews conducted with city employees participating in urban planning processes in two middle-sized cities in Finland, stakeholders of a research project on resilient urban planning. The interview guide contained questions about respondents’ job description, on their perception on how health and wellbeing is connected to urban planning processes, about multiprofessional collaboration and information used in decision-making processes from the point of view of their own profession. The participants included experts from areas such as urban planning, traffic, landscaping, promotion of well-being and environmental health and protection. Some sectors were at the heart of urban planning processes, and some worked towards the same goals but were organisationally in other units of the city organisations. The study participants were selected for an interview by reviewing units that were linked to the topics in the selected city organisations and experts from the units were sent invitations for interviews. They were also allowed to direct the invitation to their colleagues. The interviews were carried out in spring 2022.

Altogether 16 employees were interviewed in 15 interviews, as one of the interviews was a couple interview, in the others the interviewee was alone (interviewees referred in the study as I1-I16). The interviews were conducted remotely using the Teams video conferencing software. In total, we had c.a. 20 hours of interview material, which was transcribed and analysed with NVivo data analysing tool. The data was analysed in a theory driven way, based on the frame of the study outlined in Figure 1, focusing on the actions, contexts and modes of information practices identified. The coding of the data progressed in stages, starting openly from the data, focusing on the passages where the participants described their information use and working processes and practices. Then, the different actions, contexts and modes of information practices were identified.

Findings

Based on the analysis of the interview data, we present our findings on the information practices making the planning of healthy urban environments possible and focus on what kinds of information practices are developed and needed for multi-professional work.

Information use practices

The cross-sectorial professionals participating in urban planning processes used various kinds of data in their daily work. These included various themes and forms, such as maps, self-produced data (measurements, tests, samples), register data and databases (extensive data on various phenomena: residents, economy, natural phenomena, traffic, mobility), surveys and feedback, organisational reports, plans, legislation, regulations, and research knowledge. While much of the work was conducted within organisations, they also used consultants and bought some information services to produce and compile data for certain purposes. Much information was also gained from other people and in multi-professional collaboration situations and networks. The interviewees relied partly on the same or similar sources in their work, but the responses also show divisions related not only to the sources of information, but also to the form of the information used and, thus, to information practices and structures.

The participants described their working with information as the use of information, which explains how the work is done, how the information is used in decision-making, such as the basic work of the supervisory authority:

That of course, on the domestic water side, they have the results of the analysis, like if there are E. coli there. (…) They are the facts based on which you make decisions and act. If I make some statements about environmental permits, for example, I must assess the effects on health. Then there are the studies and reports that have been made there, and you will probably read them and see if everything relevant has been considered.

In these kinds of information use practices, the professionals have legislation framework, organisational structures, systems, and tools to work, and can also work quite individually doing decisions based on their expertise and the information available for them.

In the context of the city organisation, the professionals often recognise the multi-professional nature of their work and decision-making. Multi-professional collaboration or division of work in the city organisation can support their work for healthy environments. There, the information practices were often embedded in the ways in which the professionals talk about their work also in collaboration, such as we think, we find compromises, we try to take things into account:

In traffic planning, there are noise issues, and then with landscaping we think about a good place for the beach or things like that, where cooperation is really important. (…) And in school location issues, there is so much need for cooperation, (...) let's find the compromise solutions and try to take these things into account. (I5)

To make for example the compromises possible, there is a need to share and create information together in organised venues and informally, as outlined in the next chapter.

However, when working in a multiprofessional manner, the practices of using information may change and weaken, if there are changes in the organisation. It is noteworthy that the ways of collaborating can be maintained or, on the other hand, lost, in which case practices also disappear, as in this example describing challenges in the multi-professional use of information and its difficulties:

In the organisational reform these were split into separate units, i.e. the design is its own and the construction is its own unit, and the maintenance is its own unit. Before, they were all one and same organisation, so the good thing about it was that we could learn lessons at the next site, but now that information doesn't flow much, we make plans, and the developers build, and the maintainers then maintain. (I10)

In the changing situations, as well as if the support is not provided by the own community, some participants used information from organisational strategies as support of one’s own work.

Information seeking and sharing practices

The analysis of the interview data revealed that in the urban planning work, there are strong and systematic traditions of information use coming from the complex planning processes regulated by the legislation and various guidelines. Certain information seeking practices were fixed and supported by organisational systems and practices. This is reflected to the ways in which information seeking and sharing practices are organised. In urban planning, there are some systematic structures for information seeking coming from the legislation and guidelines, as well as from the practices of seeking and creating needed information to complete the task:

Or it could be that there have been complaints from the customer about something, and then we start to investigate and then act accordingly, (...) or if we talk about decisions or regulations, then there must already be facts, measurement results and some research information in the background. (I1)

As seen here, much of the work includes not only seeking existing information, but also creating needed information on situational and contextual issues. This information, for example on the quality of water, noise or other environmental factors can be shared and used within the organisation with other professionals. The seeking of needed information may be delegated to another actors, to whom some information practices are entrusted:

They bring their own expertise as an organisation to certain groups, their own kinds of facts, what their ideas are based on. It is this harmonisation of information for many of us, so that maybe that is how we use it. (I3)

Research data has a big role in the work, and information practices are developed to find and use it effectively, both individually and collectively:

I work with traffic accidents. I use much data collected from traffic accidents. There is a lot of research into it, and the Institute for Accident Research produces a huge amount of it. And then maybe the information we are utilising, I don't have the energy to read it for very long. In other words, we would need such a concise summary of the study and then the results so that we can grab hold of them, and then, if necessary, go deeper. (I12)

In addition, the practices for seeking information are embedded in the professionals’ interests in developing their expertise. Important is to know the right sources, channels, and networks, but also the usability of the information:

Of course, when there are a lot of expert networks, a lot of research data related to this field comes through LinkedIn, Twitter and from there you can pick up interesting articles and then read more. But yes, we also pretty much depend on our own interest to read it. Very differently people follow research in the field. Some don't follow at all, and some are well informed and bring it to everyone else's attention then, the best bits from there. (I12)

Information sharing practices intertwine with the practices of seeking and creating information. The interviews revealed that a diverse group of city actors and national-level producers participate in developing health, well-being, the environment and urban structure. Whether this knowledge base is available to everyone and whether actors have knowledge of the valuable information that others hold is another question:

In our sector, it is challenging, as we are quite used to operating through inspections, that the roots of this control lie in the fact that we carry out inspections and collect those milk samples or water samples, and then we should also be able to cover things more extensively so that we can really help with it. That we will help to anticipate those risks. (I1)

Information sharing links with information seeking and creation in city organisation through different collaboration groups and meetings. The participants viewed, that the personal involvement of the professionals in the multi-professional meetings and processes was important, and information was sought, gained, and shared through them. Information sharing could be formal or informal:

Well, the individual projects, of course, but then those cooperation groups and also situations where we can discuss things more freely, not so much that it is always related to a single concrete matter, but brainstorming sessions or idea workshops where we work on those things, we get to pass on the facts, information related to our own expertise, to different parties and discuss them more freely. (I3)

Important for information sharing was that there were places for interaction, and more unstructured discussions were needed in multi-professional venues. Sometimes it can be difficult:

That the creative cooperation of many people, just because it is based on the personal relationships that have been formed. The new ones are completely left out of it, because they don't have such a culture, as the relationships have already been formed earlier. And now that new ones are coming into this agenda organisation, where we will fast go through sections one, two, three or four and everyone will speak when the right to do so is given in the agenda, that makes that cooperation non-existent. (I11)

Information creation practices

The interviewees' descriptions revealed that in expert work, information creation is a central practice intertwined with other information practices – a large part of professionals’ work is compiling, analysing, and producing summaries of information, which partly involves searching for existing information resources and producing needed material. The interviewees also recognised the significance of common information practices: common documents required in decision-making were considered important ways to refine complex content related to well-being information in particular. These included, for example, the preparation of a well-being reports, which enabled the compilation of a broader knowledge base.

In the city organisation, information creation was also multi-professional, and the professionals participated in the development of a healthy environment by creating documents, plans and strategies. This work was done also by participating in groups and networks, so it was important, that different professionals had a chance to participate the work:

I am responsible for ensuring that we draw up an annual control plan and evaluate its implementation. (...) And that's what I'm trying to promote to ensure that all things are considered. And, that we are sufficiently involved in those processes, in terms of fulfilling our obligations that the legislation imposes on our sector. (I1)

Being part of the important multi-professional information creation processes within the city was seen crucial in influencing the practical decision-making related to healthy environments.

Introducing different themes into municipal decision-making can also be seen as an information practice that develops into decision-making structures as the creation and implementation of certain documents, such as strategies and plans for different themes on health, environment and urban planning, that then guide the decision-making work. Information creation as a multi-professional practice was seen as a way to influence on the city’s decision-making:

Last year, we drew up a plan for sustainable urban mobility, in which this well-being and health have been specifically highlighted, and the neighbourhood environments, the promotion of walking, cycling and public transport have been highlighted. It included urban planning, master planning, environmental side. And that's a politically approved document over there in the city government. (I3)

Shared information practices and processes in which various professionals and stakeholders were committed to information creation were considered important also because they strengthened decision-making and the acceptability of decisions.

Here, creating information was also a way to bring forth and secure health and environment related themes that were seen important, but also controversial in decision-making:

The purpose of the strategic forest plan is that from time to time we seek a backing for our own activities. On how those forests in the city should be managed. Because they are a subject to a lot of different expectations, which are partly contradictory. (...) So a balance has been sought. And it was sought from that very highest political decision-making body, i.e. the city council. So it gives us some peace of mind to work again for a while. (I9)

It can be seen that by creating information, different parties can both collaborate and, on the other hand, stand out to bring out their own points of view.

Information practices for managing and developing practices and processes

The analysis of the data also indicated, that in the changing environments, and especially when developing multi-professional work, the organisation and management of information practices was seen important. Key to the development of healthy environments was to bring together different professionals, and it required the development of interaction. Often, these places for interaction were there in the structures, and the professionals’ work was to organise and manage them:

General planning is strategic in nature and very forward-looking, it is also very interactive, bringing people and experts from different administrative branches into the same discussions and pondering together the questions. It requires us to have a wide range of discussions to support our work. (I4)

However, many professionals were concerned that their professional knowledge was not part of some important practices without constant monitoring and active involvement. The analysis illustrated, that some information practices were created by the actors themselves or managed by their own organisation, while some practices were dependent on organisational developments. The relevance of personal connections was high:

I think that personal connections are very important. (...) In such a delicate time we should make sure that we do not lose the networks that exist there. That the guy from the rescue side is involved in the technical inspection team there, so in the same way there should probably be those structures and processes where we hang on together. (I1)

The analysis showed, that the information practices in using, seeking, sharing and creating information required management and involvement of different parties, also on the organisation management level: I think it's like, the higher up you are in the organisation, the more responsibility you have to create those kinds of things, to make sure that there are those channels, that there are no gaps in between. That it's a bit difficult to start from the bottom. (I1) On a professional level, the creation and organisation of practices could happen naturally and informally, by organising a discussion with key professionals in the other units to start collaboration and information sharing:

I've just been wondering how we should be involved in environmental health in zoning, and I could have a discussion with the planner about what kind of things we want to be taken into account. (...) But it does take an awful lot of resources to think about whether we have something to give, that in a way it is a sensible use of time from us. (I1)

Here, we can see a crucial concern emerging from the data, on how to concentrate and use the time effectively in multi-professional work, as information and work tasks are manyfold.

Some participants saw the management of information and organisation of information practices, tools and systems as ways to manage with the vast amount of information and deficits in resources. However, taking use of relevant information needed time and possibilities to read and learn:

I can't confess that I read it (the welfare report). (..) our resources are deficient and the number of things to be coordinated is so huge that there would have to be someone who would constantly take care of all the factors affecting the operations of the entire unit. (I14)

In addition, the organisation work could be very time-consuming and if there was no mutual will to collaborate, the multi-professional practices can be impossible to keep alive.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this study was to examine, what kinds of information practices exist in the city organisations related to the development of healthy urban environments and what kinds of information practices are needed to develop multi-professional work. The work of city professionals can be meaningfully understood from the perspective of information and work, paying attention to both information practices and the context in which the practices take place. Thus, our research contributes to research on work-related information practices.

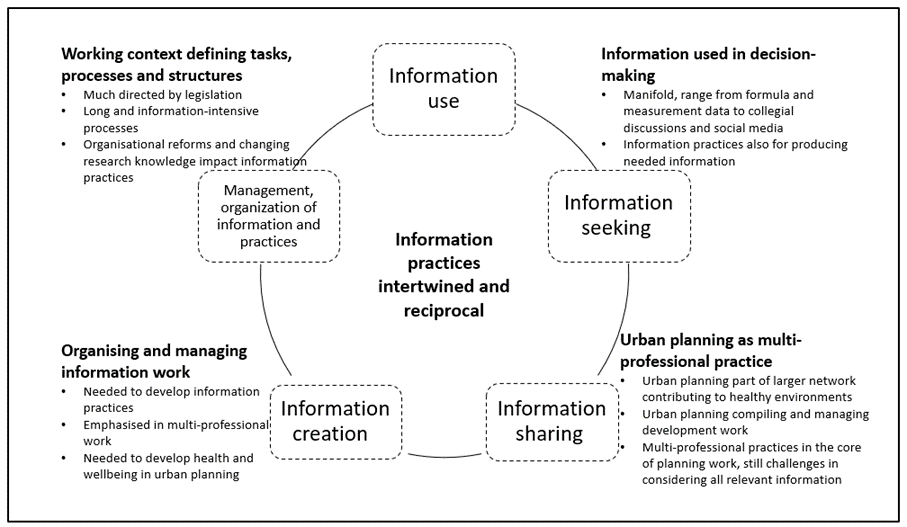

Organisational structures, societal structures and legislation, tools, resources, and the organising everyday work determine practices. In the context of urban planning, the long-term and information-intensive nature of the work shape the practices. The planning of urban environments is a process that spans decades and involves many different actors whose activities are bound by different regulations, regional structures, and social and environmental factors, seen also in Serola’s (2009) and Afida et al.’s (2017) studies on urban planning. This study expands our understanding by including the multiprofessional nature of work (see Inam, 2011). From an information perspective, the urban planning process is therefore complex and regulated, but there is a lot of room for individual consideration when forming and developing information practices. Interestingly, the complexity can be understood as we look at the wide range of information practices as using, seeking, sharing, and creating information, and acknowledge, that also organising and managing both information and information practices are needed in information-based decision-making (see also Zhong et al., 2023). This can be understood in terms of information management as co-ordinating information processes on personal and communal level. Furthermore, our findings illustrate the multi-professional nature of information practices in this context and therefore open new perspectives to this research topic. Our findings are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Information practices in city organisations in this study.

As implications to practice, the findings show that information practices regarding the seek and use of information function quite well when carrying out more simple and routine tasks; when complexity and system-wide impacts increase, also pressures on information practices grow. The organisation also has opportunities to share information, and multiprofessional work is partly part of the daily work of experts. This is made possible by various multidisciplinary working groups, networks, and projects in which the expertise of different parties is invited to participate either in joint work or in giving their statements to the process. Our findings help to make the demands of complex information-intensive work more transparent, and this might help to plan regarding policies in organisations. One implication of our study is highlighting the importance of multi-professional work in urban planning. Fostering cross-functional communication is essential for joint understanding and this needs to be guided and supported by management. Related to this, power structures should be further studied as creating an inclusive environment where all voices are heard fosters joint understanding.

Dysfunctional information practices and environments where access to and use of information are difficult have an impact on information-based decision making. This is highlighted when processes cross boundaries between organisations and when the work's premises are changing. Our findings indicate that taking care of the practices can be constant work of being present of bringing one’s own fields expertise to the important discussions. This can be challenged by the lack of time, organisational reforms and changing personal relations. Our findings suggest, as implications, that in addition to developing processes, tools and structures, there is a need to foster and develop possibilities to create and maintain information practices on the personal, communal, and organisational levels. Here, our findings are related to the information practices research in organisations highlighting the importance of both formal and informal places for information sharing and use (Pilerot and Limberg, 2011; Willson, 2022). Our findings bring fort the implications of the remote and hybrid work to the information practices, as multiprofessional work requires official and unofficial places for meeting, developing networks and places for information sharing. This calls for further investigation. In our findings, the practices of creating information, and the intertwined nature of information practices were highlighted, leaving still room for further examination (Willson, 2022). Our study related also to the studies of knowledge use in the field of Knowledge Management, and further studies are to be conducted to connect information practices to KM and IM concepts (Suorsa et al., 2019; Widén et al., 2014).

In conclusion, our study illustrates the importance of understanding information practices not as individual, but as communal and reciprocal in nature, which is embedded also in the basis of the conception (Savolainen, 2007; Talja and Hansen, 2006). Creating organisational environments and structures to support these practices is important in developing means to solve complex, multidisciplinary problems.

Acknowledgements

This study has been funded by the Strategic Research Council of the Academy of Finland (Grant number 345220).

About the authors

Anna Suorsa (PhD) is a university lecturer in the University of Oulu, Finland, in the field of Information Studies. Her research focuses on the use of information and knowledge in organizations and communities. Her fields of interest are interactive knowledge processes and practices enhancing knowledge creation, information literacy in different contexts, the use of information in decision-making and multidisciplinary collaboration. anna.suorsa@oulu.fi

Anna-Maija Multas (PhD) is a post-doctoral researcher in information studies at the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Oulu, as well as the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research focuses on information creation practices in diverse settings, including interdisciplinary and intersectional communities, as well as among young people and in relation to health and well-being. Her research methods include nexus analysis and participatory methods like co-research.

Adjunct professor (title of Docent) Emilia Rönkkö works at the Oulu School of Architecture, University of Oulu. She is specialized in evidence-informed urban planning and related theoretical and methodological approaches, which support health promotion in urban living environments. She currently works as a work package leader in the Academy of Finland`s Strategic Research project RECIPE (Resistant Cities: Urban Planning as Means for Pandemic Prevention).

Eevi Juuti is an architect and doctoral researcher at the Oulu School of Architecture at the University of Oulu in Finland. Her research focuses on design thinking and service design in the context of built environments. She has also done research on a variety of topics concerning urban planning.

Anelma Lammi works as Project Manager and Postdoctoral Researcher at Finnish Lung Health Organisation in health promotion projects. Her latest research interests include use of tobacco and nicotine products among Finnish conscripts and COVID-19 communication to citizens by Finnish public authorities.

Adjunct professor (title of Docent) Heidi Enwald works as a university lecturer in Information Studies, Faculty of Humanities at the University of Oulu. Enwald has been leading the Information Studies unit since 2021. Her research interests span various aspects of information behavior and practices, including health information needs, seeking, and use. She has also focused on health information literacy, health communication, and tailoring health information in e-health services, as well as in topics relating to open science.

References

Afida, I., Idrus, S. & Hashim, H.S. (2017). Information seeking behaviour of Malaysian town planners. Library Review, 66(4/5), 330-364. https://doi.org/10.1108/LR-04-2016-0034

Bennett, H. (2006). Bringing the Studio into the Library: Addressing the Research Needs of Studio Art and Architecture Students. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 25(1), 38–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27949400

Bronstein, J. & Solomon, Y. (2021). Exploring the information practices of lawyers. Journal of Documentation, 77(4), 1003-1021. https://doi.org/10.1108/jd-10-2020-0165

Byström, K. & Järvelin, K. (1995). 31(2), 191-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(95)80035-R

Byström, K. & Kumpulainen, S. (2020). Vertical and horizontal relationships amongst task-based information needs, Information Processing & Management, 57(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102065

Case, D.O. & Given, L.M. (2016). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior, 4th ed., Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley.

Choo, C. W. (2006). The knowing organization. How organizations use information to construct meaning, create knowledge and make decision. Oxford University Press.

Citroen, C.L. (2011). The role of information in strategic decision-making. International Journal of Information Management, 31(6), 493–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.02.005

Davoudi, S. (2006). Evidence-based planning: rhetoric and reality. The Planning Review, 42(165), 14-24.

Dervin, B. (1983). An overview of sense‐making research: concepts, methods, and results to date. Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, Dallas, TX.

Dervin, B. (1999). On studying information seeking methodologically: the implications of connecting metatheory to method. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 727‐50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00023-0

Dervin, B. & Frenette, M. (2003). Sense‐making methodology: communicating communicatively with campaign audiences. in Dervin, B. and Foreman‐Fernet, L. (Eds), Sense‐making Methodology Reader. Selected Writings of Brenda Dervin, Hampton Press, Cresskill, NJ, pp. 233‐49.

Du, J.T. (2014). The information journey of marketing professionals: Incorporating work task-driven information seeking, information judgments, information use, and information sharing. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(9): 1850-1869. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23085

Eliasson, I. (2000). The use of climate knowledge in urban planning, Landscape and Urban Planning, 48(1–2): 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(00)00034-7

Elliott, A. (2001). Flamenco image browser: Using metadata to improve image search during architectural design. In Proceedings of ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (ACM CHI 2001) (pp. 69–70). New York: ACM Press.

Faehnle, M., Bäcklund, P. Tyrväinen, L. Niemelä, J., & Yli-Pelkonen, V. (2014). How can residents’ experiences inform planning of urban green infrastructure? Case Finland. Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 130: 171-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.07.012

Faludi, A., & Waterhout, B. (2006). Introducing evidence-based planning. The Planning Review, 42(165), 4-13.

Fonseca, F.T., Egenhofer, M.J. Davis, C.A. & Borges, K.A.V. (2000). Ontologies and knowledge sharing in urban GIS. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, 24(3): 251-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0198-9715(00)00004-1

Gorichanaz, T. (2019). Information creation and models of information behavior: Grounding synthesis and further research. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 51(4): 998–1006. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000618769968

Inam, A. (2011). From dichotomy to dialectic: Practising theory in urban design. Journal of Urban Design, 16:2: 257-277, https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2011.552835

Jacobs, F., Jordhus-Lier, D. & de Wet, P.T. (2015). The politics of knowledge: Knowledge management in informal settlement upgrading in Cape Town. Urban Forum 26, 425–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-015-9258-4

Koh, K. (2013). Adolescents’ information-creating behavior embedded in digital media practice using Scratch. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(9): 1826–1841. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22878

Leckie, G.J., Pettigrew, K.E. & Sylvain, C. (1996). Modelling the information seeking of professionals: a general model derived from research on engineers, health care professionals and lawyers. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 66(2), 161-193. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4309109.

Li, Y. & Belkin, N.J. (2010). An exploration of the relationships between work task and interactive information search behavior. Journal of The American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(9), 1771-1789. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20977

Lloyd, A. (2010). Framing information literacy as information practice: site ontology and practice theory. Journal of Documentation, 66(2), 245-258.

Lloyd, A. & Olsson, M. (2017). Being in place: Embodied information practices. Information Research, 22(1). http://informationr.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1601.html

Lloyd, A. & Olsson, M. (2019). Untangling the knot: The information practices of enthusiast car restorers. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(12), 1311-1323. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24284

Lowe, M., Whitzman, C., Badland, H., Davern, M., Aye, L., Hes, D., Butterworth, I., & Giles-Corti, B. (2015). Planning healthy, liveable and sustainable cities: How can indicators inform policy? Urban policy and research, 33(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2014.1002606

Lysgård, H. K., & Cruickshank, J. (2013). Creating attractive places for whom? A discourse-theoretical approach to knowledge and planning. Environment and planning a: economy and space, 45(12), 2868-2883. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45607

Makri, S. & Warwick, C. (2010). Information for inspiration: Understanding architects' information seeking and use behaviors to inform design. Journal of American Society of Information Science, 61: 1745–1770. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21338

McGuirk, P. M. (2001). Situating communicative planning theory: Context, power, and knowledge. Environment and planning a: Economy and space, 33(2), 195-217. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3355

McKenzie, P.J. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

McKenzie, P.J. (2010). Informing relationships: small talk, informing and relationship building in midwife-woman interaction. Information Research, 15(1), paper 423. http://InformationR.net/ir/15-1/paper423.html

Merikoski, T., Staffans, A., & Syrman, S. (2022). Growth target as a barrier to knowledge integration and provision of alternative scenarios in urban planning. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 1122 012012. http://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1122/1/012012

Mitchell, R., Nicholas, S., & Boyle, B. (2009). The Role of Openness to Cognitive Diversity and Group Processes in Knowledge Creation. Small Group Research, 40(5): 535–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496409338302

Nieuwenhuijsen M. (2021). New urban models for more sustainable, liveable and healthier cities post covid19; reducing air pollution, noise and heat island effects and increasing green space and physical activity. Environment International 157, 106850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106850

Nordsteien, A. & Byström, K. (2018), Transitions in workplace information practices and culture: The influence of newcomers on information use in healthcare. Journal of Documentation, 74(4), 827-843. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2017-0116

Pilerot, O. (2012). LIS research on information sharing activities – people, places, or information. Journal of Documentation, 68(4), 559-581. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411211239110

Pilerot, O. & Limberg, L. (2011). Information sharing as a means to reach collective understanding: A study of design scholars' information practices. Journal of Documentation, 67(2), 312-333. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411111109494

Savolainen, R. (2007). Information Behavior and Information Practice: Reviewing the “Umbrella Concepts” of Information‐Seeking Studies. The Library Quarterly, 77(2), 109-132. https://doi.org/10.1086/517840

Savolainen, R. (2008). Everyday Information Practices: A Social Phenomenological Perspective, Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD.

Savolainen, R. & Kari, J. (2006). User‐defined relevance criteria in web searching. Journal of Documentation, 62(6), 685‐707. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410610714921

Serola, S. (2006). City planners' information seeking behavior: information channels used and information types needed in varying types of perceived work tasks. Teoksessa Proceedings of the 1st international conference on Information interaction in context (IIiX) (s. 42–45). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1164820.1164831

Serola, S. (2009). Kaupunkisuunnittelijoiden työtehtävät, tiedontarpeet ja tiedonhankinta [PhD thesis, University of Tampere]. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis, 1384. (In Finnish).

Suorsa, A., Suorsa, T., & Svento, R. (2019). Materiality and embodiment in collaborative knowledge processes: Knowledge creation for a virtual power plant. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Ljubljana, Slovenia, June 16-19, 2019. Information Research, 24(4), paper colis1930. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1930.html

Talja, S. & Hansen, P. (2006). Information Sharing. In: Spink, A., Cole, C. (eds) New directions in human information behavior. Information science and knowledge management, vol 8. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3670-1_7

Taylor, R. S. (1991). Information use environments, in Dervin, B. and Voigt, M.J. (eds), Progress in Communication Sciences, Ablex, Norwood, NJ, 217–255.

von Richthofen, A., Herthogs, P., Kraft, M., & Cairns, S. (2022). Semantic city planning systems (SCPS): A literature review. Journal of Planning Literature, 37(3), 415-432. https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122211068526

Widén, G., Steinerová, J. & Voisey, P. (2014). Conceptual modelling of workplace information practices: a literature review. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014: Part 1, (paper isic08). Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic08.html

Willson, R. (2022). “Bouncing ideas” as a complex information practice: information seeking, sharing, creation, and cooperation. Journal of Documentation, (78)4, 800-816. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-03-2021-0047

Zhong, H., Han, Z. & Hansen, P. (2023). A systematic review of information practices research. Journal of Documentation, 79(1), 245-267. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-02-2022-0044