Information Research

Special Issue: Proceedings of the 15th ISIC - The Information Behaviour Conference, Aalborg, Denmark, August 26-29, 2024

Surfacing the ‘silent foundation’: which information behaviour theories are relevant to public library reference service?

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/ir292849

Abstract

Introduction. Despite extensive discussions on the theory/practice gap in library and information science, there is a paucity of research on the value and use of formal theory by librarians in their daily practice.

Method. Our card sort and interview study investigated which information behaviour theories were relevant to public librarians from Slovenia and the United States in their reference practice and how they encounter those theories in their practice.

Results. All of the information behaviour theories were considered relevant by some of the participants. Bounded rationality or “satisficing” was seen as most relevant for information service, while the key difference between Slovenian and United States librarians was observed in their perception of “information poverty”. Participants were generally able to provide examples of how the theories were used in practice, but usually did not recall learning about the theory or the theory’s name.

Conclusion. Information behaviour theory is relevant to reference practice in public libraries although its use by librarians may be implicit. These findings may be useful to instructors in LIS programs to convey to students the value of learning theory. Questions remain about why librarians find certain theories more relevant than others and what factors contribute to the differences in their perceptions.

Introduction

One goal for information behaviour theories, models, and concepts is their application to practice contexts, such as the interaction between a librarian and a user during reference service. Knowledge of information behaviour theories can help librarians understand what their users are thinking, feeling, and doing; suggest solutions to users’ information challenges; and guide user instruction. However, little research has been conducted on the extent to which specific theoretical models and concepts are used in practice. As a result, information behaviour scholars have little feedback about whether their theories, models, and concepts are useful for practice or effectively communicated to practitioners. Educators also lack information about whether the theories, models, and concepts they teach are the most appropriate ones or whether they are being presented most effectively for future practitioners to learn.

Wakeling et al. (2019) suggest that although librarians may not view theory as pertinent to their practical work, they may be implicitly using it to structure their existing knowledge or as a ‘silent and essential foundation’ for practical work (p. 789). Our research is aimed at exploring this ‘silent foundation’ by identifying which information behaviour theories, concepts, and models are known and used by librarians in their information service work, specifically in the context of public library reference work. To follow this aim, we posed two research questions:

Which information behaviour theories, concepts, and models do public librarians consider relevant to their information service, and how familiar are they with these theories?

How do they encounter them in practice?

Given the international reach of information behaviour research, the team posed a third research question to examine potential differences between their respective international contexts (Slovenia and the United States):

How does relevance of information behaviour theories, models, and concepts differ by country?

The term theory will be used loosely throughout the paper to refer to formal theories, models, and concepts, as is common in research on the topic in the information behaviour literature (e.g., Lund, 2019; Pettigrew and McKechnie, 2001).

Literature review

Ideally, theory, once developed and tested, should be learned and adopted by students and practitioners and used to improve practice. However, that is not always the case. The library and information science (LIS) literature is rife with discourse of a disconnect between theory and practice (e.g., Abbas et al., 2016; Bawden, 2008; Haddow and Klobas, 2004; Nguyen and Hider, 2018). Practitioners argue that the theory they learned during their LIS education is not relevant to their daily work (e.g., Kern, 2014) and instructors feel that many students are not open to learning about theory (VanScoy et al., 2022). This disconnect is a global phenomenon, as argued by Matusiak et al. (2024).

Bawden and Robinson (2022) and Wakeling et al. (2019), however, suggest that even if librarians do not refer to theory in their daily work or consider it relevant to their practical work, theory might still influence their professional knowledge. Practitioners could be using it subconsciously to structure their existing knowledge, serving as a ‘silent but essential foundation’ to their practical work (p. 789). Only a few studies have attempted to test this notion in the discipline. In one such study, Schroeder and Hollister (2014) conducted a survey to explore American librarians' familiarity with and usage of critical theory. The majority of participants stated that they were knowledgeable about critical theory and were able to provide an example of how they have applied it in their work. However, the authors did not examine whether the examples provided by participants accurately applied critical theory. Pinfield et al. (2020) conducted interviews to determine whether open access theory was relevant to practical applications. Participants were asked if theory had influenced their understanding of open access and how it had informed their practical work. The study did not focus on the use of any specific theory, but rather on research that incorporates theory. Only a small number of participants could clearly identify instances when they had used theory to inform their practical work. However, researchers observed that during the interviews, many participants referred to various theoretical concepts without even knowing and some acknowledged the possibility of using theory subconsciously. These two studies suggest that librarians see theory as informing their practice, yet the application may not be explicit.

This study focuses specifically on information behaviour theory as it informs reference practice. A number of studies have determined which information behaviour theories are considered most influential or important in the research literature, notably Pettigrew and McKechnie (2001), McKechnie et al. (2005), McKechnie et al. (2008), and Lund (2019). VanScoy et al. (2023) used these lists of top information behaviour theories to study which ones were considered by North American LIS instructors to be the most important for reference service education. The most frequently taught information behaviour theories are listed below in order of importance:

Kuhlthau’s (1991) information search process

Savolainen’s (1995) everyday life information seeking

Taylor’s (1968) information need

Dervin’s (1992) sense making

Belkin’s (1982) anomalous states of knowledge

Chatman’s (1996) information poverty

Simon’s (1955) bounded rationality

Chatman’s (1991) gratification theory

Wilson’s (1981) model

Wilson’s (1999) revised model

Bates’s (1989) berrypicking

Ellis’s (1989) model

This list of information behaviour theories provided a good starting point for the current research.

Methods

Choosing a methodology to investigate the use of theory in practice was a challenge. An ideal choice might be a think-aloud protocol while librarians responded to reference inquiries with a follow-up interview. Given the disruption to service this procedure would cause, the team explored other options. Methods used in similar studies in LIS were interviews (Pinfield et al., 2020) and surveys (Schroeder and Hollister, 2014). Outside LIS, De Swardt et al. (2012) used guided reflection and written narratives of a critical incident to study nursing students' use of theory. Kwenda et al. (2017) utilized a guided reflection framework, which involves formal, structured reflection with the assistance of a facilitator during focus groups to investigate student teachers' use of theory in their teaching. Tsangaridou and O’Sullivan (1997) used observations of lessons, interviews, and discussions of scenarios to investigate the extent to which education theories guide the practice of physical education teachers.

The research team decided to use a card sort exercise coupled with interviews. Given that practitioners generally have a negative view of theory, we wanted a method that would generate interest in the topic and help librarians engage with it. In addition, we thought that the process of reading and physically manipulating the cards might help librarians deal with the abstract nature of theory. Conrad and Tucker (2018) argue that ‘card-sorting exercises strengthen the participant’s ability to externalise their experiences and interact with the concepts represented by the digital or physical cards’ (p. 398). The research team wanted to avoid making librarians feel like they were being evaluated on their knowledge, so procedures were designed to be respectful of their practice expertise. The team also discussed the significance of librarians being able to name and explain theories. Ultimately, it was decided that it was more important to explore specific situations from reference work that practitioners related to the individual theory and the relevance of each theory to their practice. Each card therefore featured a brief description of the theory’s main contribution in plain language, with the theory or model name and creator on the back of the card for reference. The cross-cultural aspect of the project also posed some challenges, as the team had to consider differences in professional education and language. All study materials had to be prepared in both English and Slovenian, but achieving exact translations was not always feasible due to differences in the languages and specific professional terminology.

Development of theory cards

Twelve theories were selected for the study: eleven of the top twelve theories from VanScoy et al. (2023) were selected; only Wilson’s (1981) model was not chosen, as Wilson’s (1999) model was assumed to be a revision of his previous work. In place of Wilson’s (1981) model, Gross’ (1995) imposed query was added by the team because of its clear connection to reference service. Each theory was described using practical, professional language rather than formal, scholarly language. The descriptions were translated into Slovenian by two members of the research team. A group of four experts in the field reviewed the descriptions for accuracy and provided feedback for revision. These experts included Dr. Jenna Hartel, University of Toronto; Dr. Heidi Julien, University at Buffalo; Dr. Polona Vilar, University of Ljubljana; and Dr. Maja Žumer, University of Ljubljana. After several revisions, the final descriptions were then printed onto cards to be used for sorting. To further improve the descriptions, we conducted a pilot test with three librarians from Slovenia and two librarians from the United States. Based on the reactions of the librarians in the pilot test, we further revised the descriptions and reprinted the cards. Table 1 shows the final selection of theories and their plain language descriptions.

| Information behaviour concept | Plain language description |

|---|---|

Anomalous state of knowledge (Belkin, 1982) |

A person recognizes a gap in their state of knowledge which they search for information to rectify. The person evaluates the information found to determine if it resolves this gap. If it is resolved, the information seeking may end, otherwise the process is repeated. |

| Berrypicking (Bates, 1989) | People seek information in an iterative way. The search they enter into an information system is likely to evolve as more is learned. Their search strategies and questions may also vary along the way. |

| Bounded rationality (Simon, 1955) or “satisficing” | Due to time or other constraints, people make selections that are good enough, rather than optimal. |

| Everyday life information seeking (Savolainen, 1995) | Sometimes people encounter a problem or a project that disrupts their orderly way of life. Depending on their own psychology and their sociocultural situation, they use various means to seek information and return their everyday life to an orderly state. |

| Gratification theory (Chatman, 1991) | Due to pressing economic and psychological problems, some people seek immediate gratification by using information that is readily accessible and easy to use in the moment of need. |

| Imposed query (Gross, 1995) | Sometimes a person asks a librarian for help with an information need that is really someone else’s information need. This can cause confusion or misinterpretation because the librarian is not communicating with the person who has the need. |

| Information need (Taylor, 1968) | A person has an actual, but unexpressed need which comes to their conscious mind as an ill-defined question which the person forms into a formal question which they then share with a librarian or enter into an information system. |

| Information poverty (Chatman, 1996) | People who have limited access to information may develop distrust in the information provided by those they perceive as outsiders. |

| Information search process (Kuhlthau, 1991) | As people progress through the information seeking process, they take various actions and their thinking becomes clearer and more focused. They experience a range of emotions that may include anxiety, confusion, doubt, relief, satisfaction, or disappointment. |

| Information seeking model (Ellis, 1989) | The process of looking for information includes searching, following references, browsing, filtering, and selecting sources based on judgement of quality and relevance. It also involves checking accuracy and checking that all material was covered. |

| Model of information seeking (Wilson, 1999) | When a person is in a problematic situation, they want to advance from uncertainty to certainty via information-seeking. As they move through stages in the information seeking process their uncertainty is reduced. If their uncertainty isn’t reduced, they may go back to a previous stage of the process. |

| Sense-making (Dervin, 1992) | As people move through life, their forward progress is sometimes arrested by a lack of knowledge, which is perceived metaphorically as a gap. They seek information that allows them to overcome the gap and then accomplish their original aims. |

Table 1. Information behaviour concepts and their plain language descriptions

Participants

We chose to focus specifically on public librarians who have reference service responsibilities and formal LIS education. The participants were selected through convenience and snowball sampling. The study involved 20 public librarians (10 from Slovenia and 10 from the United States), who predominantly served adults or users of all ages. Both Slovenian and United States participants had similar profiles in terms of work experience, ranging from those fairly new to the profession with only two years of experience, to those very experienced, with up to 30 years of providing reference service.

Procedures

A member of the research team met with each participant for 30-60 minutes, either in person or online using Zoom. Study procedures were explained, and verbal consent was obtained. In-person participants were asked to sort the physical cards based on the prompt, ‘Which of these concepts are relevant to your reference work?’ For online participants, virtual cards were recreated using Zoom’s whiteboard feature. Participants were able to control the whiteboard to move the virtual cards around the screen, and the research team member could see the movement and record a screenshot of each participant’s final card sort arrangement. For relevant concepts, the participants were asked to provide an example from their practice. In-person participants were invited to turn over the cards to see the theory names if they were interested. For interested online participants, the research team member told the names of the theories. The participants were asked if they recognized the theories or theorists, and if so, where they learned about them. Lastly, they were asked to sort the relevant cards into like groups to demonstrate how they perceived their similarities and differences. Participants provided explanations for their groupings. Results from this final activity will not be reported in this paper, as they fall outside its scope. The interviews were audio-recorded for analysis. Physical card sorts were photographed, and online card sorts were screen-captured.

Results

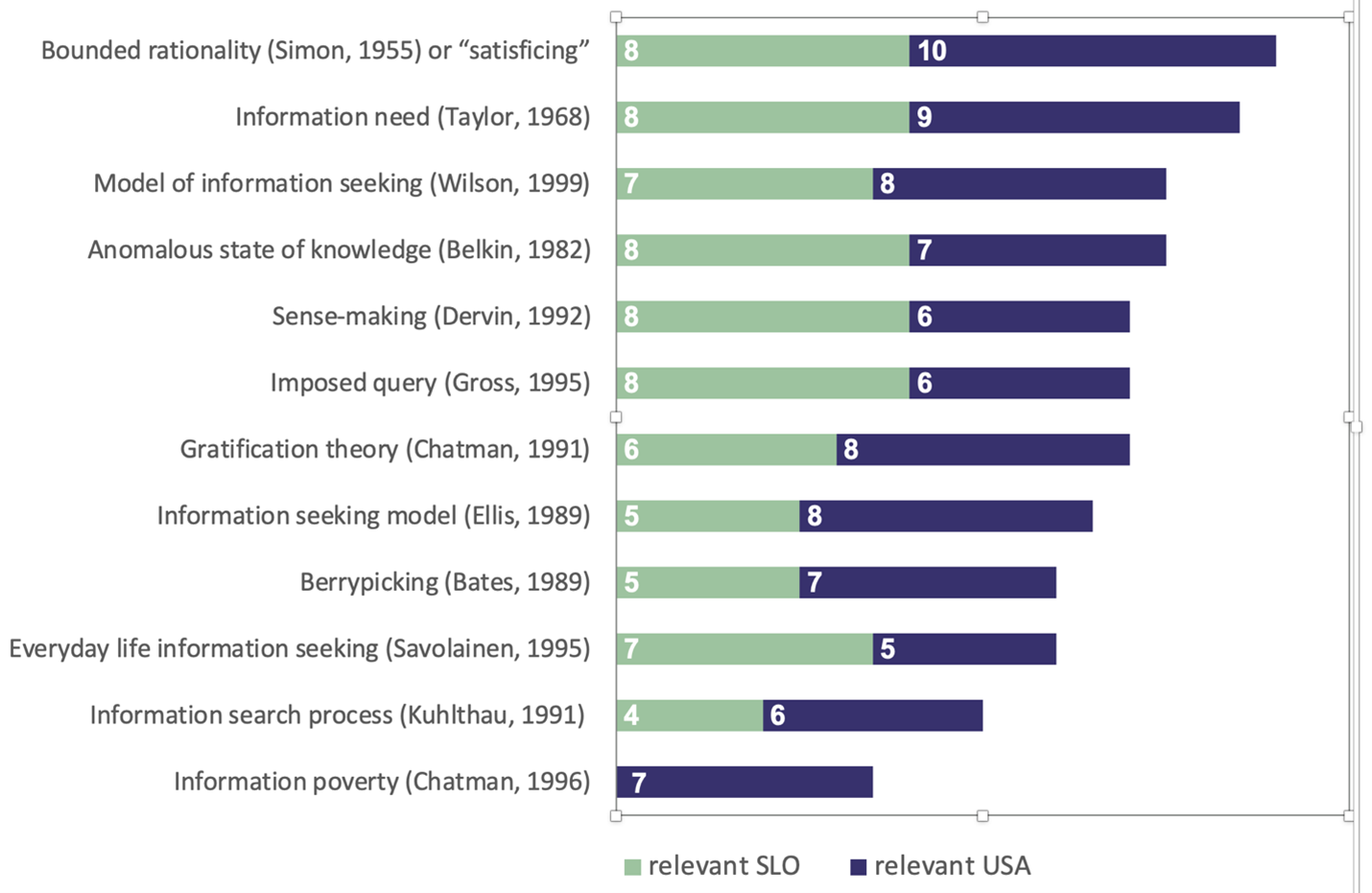

Each of the concepts was considered relevant to reference practice by at least some participants (see Figure 1). The concept deemed relevant to the most participants was Simon’s (1955) bounded rationality: 18 of the 20 participants found it relevant. A representative comment from one participant was, ‘Oh, my goodness, yeah, satisficing all the time!’

Figure 1. Number of participants who found a particular concept relevant to their practice by country.

The concept that the fewest participants found relevant to practice was Chatman’s (1996) information poverty. Only participants from the United States found this concept relevant. Pearson Chi-Square tests showed that among the 12 theories, the differences in relevance selection between the two countries were statistically significant only for Chatman’s information poverty theory, χ²(1, N = 20) = 10.77, p = .001. However, there were no significant differences in the selection of relevant theories among participants based on their years of experience working in public libraries.

When participants identified concepts as relevant, they were often expressive in their responses, using exclamations like ‘Absolutely, 100%. This is totally true and is very relevant to my job.’ When participants stated that concepts were not relevant to their practice, they sometimes suggested that a concept might be more relevant in another context, such as the academic library, as exemplified by this comment about Kuhlthau’s information search process: ‘I would imagine it would be more true in an academic library, maybe where people are doing more in-depth research.’ Other times they stated that the concept was relevant but did not occur often, as with the librarian who said, ‘Every now and then this is part of what I do, for some people.’ Some participants stated that a concept was not particularly relevant to their practice, but still, they came up with an example of how they encountered it in practice. We considered several interpretations for this response. One explanation might be that the examples librarians provided served as a tool for reflection about the theory -- a sort of think-aloud for them to make sense of the described theory. Some participants related a narrative of practice and in the end, made the final judgement that the theory was not relevant. Another possible explanation is that participants might have conflated relevance and frequency, as in this example: ‘I'm sure it does happen, but it's not something I personally deal with a lot.’

Participants were generally able to offer examples of how the concepts manifested in practice. One participant described this scenario as an example of how Gross’ (1995) imposed query manifests in her work:

Another place we see it come up is when we have, you know, an immigrant family. Sometimes one or more members will not speak English or not have very good English, and then somebody whose English is better is trying to translate the need for that person. And if that person is there and their family member is a good interpreter, that can work out okay. But if they've just sent the person with the best English to find out the information about X, Y, or Z thing that can be kind of complicated because having the language to describe the problem does not necessarily mean having the knowledge to describe the problem.

Occasionally, a participant had to think for a minute about a good example, but for most of the concepts, participants readily provided an example.

In a few instances, participants recognized the plain language descriptions and offered the name or theorist. For example, in reaction to the description of bounded rationality, one participant said, ‘Never mind. It was going to be a super off-topic story about Herbert Simon, who came up with that phrase, but you know what I'll leave that for another day.’ The description of information poverty inspired one participant to say:

It kind of reminds me of some of the stuff I read by Elfreda Chatman when I was in grad school which I've always been really interested in, but don't really have time to engage with as part of my daily work.

More often, the participants were familiar with the concept described but did not know the actual name. Participants recognized the terms berrypicking, certainty/uncertainty, satisficing, imposed query, unexpressed needs, information poverty, information gap, and sense-making. One participant explained,

I tend to think more in concepts than the titles. I take in what it means and what it means for what I do, but I don't really retain the name of the process. I remembered the information gap one because I use that to explain to people.

Some participants remembered learning about the theory and even remembered the professor who taught them the theory but did not recall the name of the theory or theorist.

Participants stated that they tend to use the concepts implicitly in their practice, rather than explicitly thinking about a particular concept. This participant’s words were similar to those of most of the participants: ‘I've definitely heard most of these terms, but like I said, they're not really something that I think about on a day-to-day basis when I'm actually helping people with their information needs.’ One participant tried to explain to us how she thinks this works:

I would say it's probably more implicit. But I also think that I'm probably influenced by learning about it… My brain isn't like ‘What is their unconscious need?’ But I might be like ‘What do they actually need?’… I feel like [his] theory has worked its way into my brain. So even though I'm not using the language that [he] uses, I definitely think that it encourages me to dig deeper into what they're looking for.

On the other hand, two participants reported explicitly thinking about berrypicking while doing reference work. One of these participants explained ‘The only one I do is berrypicking. Just because I have shared that term with other staff.’

Librarians sometimes mentioned that concepts weren’t relevant to their practice in their current library but would have been relevant in a different library where they previously worked suggesting possible cultural and contextual significance for some of the theories.

Discussion

This study may be the first to explore the extent to which theories and models of information behaviour are diffused into reference practice. It indicates that public librarians find some information behaviour theories relevant for reference practice and that theory crosses over into practice.

All of the theories were considered relevant by at least some librarians. This finding supports the selection of the twelve theories, including the addition of Gross’ (1995) imposed query. A curious finding is that only American librarians found Chatman’s (1996) information poverty relevant to their practice. After some discussion about this finding, the research team considered several possible explanations. Many of the Slovenian librarians were from rural libraries where they may not be as readily exposed to socio-economic outsider groups as urban librarians. The small qualitative nature of the study does not allow for us to test this theory; we plan to conduct future research to investigate the influence of library context and librarian characteristics on librarians’ opinions about theory relevance. Another possible explanation is the current context of heightened awareness of racism in libraries in the United States. In response to this theory, some American participants acknowledged the distrust that some marginalized community members have for American institutions. One participant related this story:

We have a very large Guatemalan population. And when ICE [United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement] comes through, they disappear. We're in a stage now where we're starting to get the moms and the kids and the families back in. And I've seen it before. Because they don't know who to trust. And even getting them in the door for story times, it's a matter of who can you trust. I mean, we are in a constant process of teaching them that we can be trusted.

There are some differences between which theories participants found important to practice and those considered most important by reference course instructors or information behaviour scholars. For example, instructors of reference courses in the United States consider Kuhlthau’s (1991) information search process model the most important information behaviour concept for their courses. However, in our study, only half of the participants thought it was relevant to their practice. This finding could indicate that LIS instructors are not teaching the information behaviour theories that are most relevant for reference practice. On the other hand, it may be due to the fact that our participants were from the public library context. One participant reacted to this theory by saying, ‘this feels more like an academic librarian’s experience than a public librarian experience.’ Two participants specifically mentioned that, in the public library, librarians do not follow students through the whole process. Another difference involves Gross’ (1995) imposed query which is not frequently included in reference courses but was added to this study because of our hunch that the concept would be relevant. In fact, it was considered relevant to reference practice by many participants.

In his study of the use of information behaviour theory in the literature, Lund (2019) found a relationship between the year a theory was published and its use by scholars in the field, suggesting that simple knowledge of a theory, whether through reading or LIS coursework, might account for its popularity. Our findings seem to support this claim since librarians found the oldest theories most relevant to their practice. Future studies should look more closely at the characteristics of theories that librarians find more relevant, which would be relevant to information behaviour scholars who want to help make their work useful for practice.

The plain language summaries may prove useful for other research on information behaviour theories, models, and concepts. While questions remain about the effectiveness of the summaries, efforts by experts in the domain could improve the descriptions, as well as provide descriptions for other theory that we did not include. The plain language descriptions would be useful for studying the relevance of these theories to other library environments, beyond the public library, and may also aid in understanding how users perceive information behaviour or how LIS students relate theories to practice. This aligns with the findings of Pinfield et al. (2020), who note that practitioners find theories difficult to understand in their original form and suggest that summaries would help practitioners more quickly grasp the point of conceptual papers.

It may be that some concepts were considered less relevant due to the plain language summary used. It was a challenge to summarize these complex and nuanced theories, models, and concepts into one or two sentences. We aimed to capture the essence of the concept. However, we sometimes chose to summarize one aspect of a concept that we deemed particularly relevant to reference practice. One of our information behaviour experts acknowledged this challenge in her comment: ‘I sometimes found your text focused on only the most ‘famous’ aspects of the theory… But I understand that you need to focus the attention of your informants, without getting tangled up in intellectual history.’

While we found the card sorting method effective for exploring participants’ familiarity with and use of information behaviour theory, the team is eager to understand the differences of opinion that surfaced between participants. We plan to design a survey instrument that will allow us to examine how factors such as LIS program, country, type of library, rural/urban setting, etc. affect librarians’ familiarity with and perceived relevance of particular theories.

The findings may be useful for curriculum decisions in information behaviour or reference courses. Students often do not understand the value of conceptual and theoretical knowledge in their library and information science education, and instructors struggle to help students see the relevance of this knowledge for their practice (VanScoy et al., 2022). The findings of this study may help instructors bridge this theory/practice gap by demonstrating that librarians find these concepts relevant and by providing practical examples of how they are relevant. Instructors might want to use the results in conjunction with other studies to help persuade students of the value of learning formal theories and models in the information behaviour or the reference course. Hearing the voices of practising librarians discussing the theories might help students understand their value. Quotes like this one might help persuade students of the value of studying these concepts:

It's one of those things I think, when you're talking about it. Library school. If you've never done it. It just may not seem like it's that practical. But once you are actually doing it. I think that information kind of retroactively becomes practical in a way.

To bridge the gap between theory and practice, researchers have suggested that there should be improved communication and translation of research into practice (McKechnie et al., 2008), increased collaboration between researchers and practitioners (Abbas et al., 2016; Haddow and Klobas, 2004), and strengthening of theory in professional education (VanScoy et al., 2022). With the attrition of library and information studies in some countries and the uncertainty about the future of the discipline (Marcella and Oppenheim, 2020), it becomes even more crucial to strengthen the connection between theory and practice and to make information science knowledge relevant to librarians.

Conclusion

Information behaviour theory is being used by public librarians as a silent foundation for their practice. Our results suggest that the theory/practice gap is not as wide as commonly reported and may be bridged through more discussion about information behaviour theories among practitioners or in the LIS classroom. Scholars may want to work toward dispelling this unhelpful discourse through research. Although it remains to be seen whether theory from other subdisciplines of information science, such as information retrieval or information management, cross over into practice as well as information behaviour theory does.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency, bilateral project BI-US/22-24-173 (Understanding and application of information science concepts and theories among librarians) and research core funding P5-0361 (Modelling of Bibliographic Information Systems).

About the authors

Amy VanScoy is an associate professor in the Department of Information Science at the University at Buffalo, NY, USA. Her research explores professional work and practitioner thinking in library and information science. She holds a PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She can be reached at 525 Baldy Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260 USA or vanscoy@buffalo.edu.

Africa S. Hands is an assistant professor in the Department of Information Science at the University at Buffalo, NY, USA. Her research focuses on library services to historically marginalised communities including nontraditional and first-generation students and LIS education. She holds a PhD from Queensland University of Technology. She can be reached at 523 Baldy Hall, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260 USA or africaha@buffalo.edu

Katarina Švab is an assistant professor in the Department of Library and Information Science and Book Studies at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Her research focuses on user studies and user experience in bibliographic information systems, and the evaluation of library services. She holds a PhD from the University of Ljubljana. She can be reached at Aškerčeva 2, Ljubljana, Slovenia or .

Tanja Merčun is an associate professor in the Department of Library and Information Science and Book Studies at the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Her research focuses on human-computer interaction, design of bibliographic information systems, and user experience in virtual and physical library spaces. She holds a PhD from the University of Ljubljana. She can be reached at Aškerčeva 2, Ljubljana, Slovenia or mercunt@ff.uni-lj.si

References

Abbas, J., Garnar, M., Kennedy, M., Kenney, B., Luo, L., & Stephens, M. (2016). Bridging the divide: Exploring LIS research and practice in a panel discussion at the ALISE’16 conference. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 57(2), 94-100. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis.57.2.94

Bates, M. J. (1989). The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Review, 13(5), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb024320

Bawden, D. (2008). Smoother pebbles and the shoulders of giants: The developing foundations of information science. Journal of Information Science, 34(4), 415-426. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551508089717

Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2022). Introduction to information science (2nd ed,). Facet.

Belkin, N.J., Oddy, R.N. & Brooks, H.M. (1982). ASK for information retrieval: part I. Background and theory. Journal of Documentation, 38(2), 61-71. doi:10.1108/eb026722

Chatman, E. A. (1991). Life in a small world: Applicability of gratification theory to information-seeking behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(6), 438–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199107)42:6%3C438::AID-ASI6%3E3.0.CO;2-B

Chatman, E.A. (1996). The impoverished life-world of outsiders. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 47(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199603)47:3%3C193::AID-ASI3%3E3.0.CO;2-T

Conrad, L. Y., & Tucker, V. M. (2019). Making it tangible: Hybrid card sorting within qualitative interviews. Journal of Documentation, 75(2), 397-416. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-06-2018-0091

Crowley, W. A. (2005). Spanning the theory-practice divide in library and information science. Scarecrow Press.

Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind’s eye of the user: The sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. In J. D. Glazier & R. R. Powell (Eds.), Qualitative research in information management (pp. 62–84). Libraries Unlimited.

De Swardt, H. C., Du Toit, H.S., & Botha, A. (2012). Guided reflection as a tool to deal with the theory-practice gap in critical care nursing students. Health SA Gesondheid, 7(1), 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v17i1.591

Ellis, D. (1989). A behavioural approach to information retrieval system design. Journal of Documentation, 45(3), 171–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026843

Gross, M. (1995). The imposed query. RQ, 35(2), 236-243.

Haddow, G., & Klobas, J. E. (2004). Communication of research to practice in library and information science: Closing the gap. Library & Information Science Research, 26(1), 29-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2003.11.010

Hall, H., Cruickshank, P., & Ryan, B. (2019). Closing the researcher-practitioner gap: An exploration of the impact of an AHRC networking grant. Journal of Documentation, 75(5), 1056-1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-12-2018-0212

Kern, M. K. (2014). Continuity and change, or, will I ever be prepared for what comes next? Reference and User Services Quarterly, 53(4), 282-285.

Kwenda, C., Adendorff, S., & Mosito, C. (2017). Student-teachers' understanding of the role of theory in their practice. Journal of Education (University of KwaZulu-Natal) 69, 139-160.

Kuhlthau, C. C. (1991). Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42, 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199106)42:5%3C361::AID-ASI6%3E3.0.CO;2-%23

Lund, B. D. (2019). The citation impact of information behavior theories in scholarly literature. Library & Information Science Research, 41(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2019.100981

Marcella, R., & Oppenheim, C. (2020). Does education in library and information studies in the United Kingdom have a future? Education for Information, 36(4). https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-200370

Matusiak, K. K., Bright, K. M., & Schachter, D. (Eds.). (2024). Bridging research and library practice: Global perspectives on education and training. de Gruyter.

McKechnie, L. E., Goodall, G. R., Lajoie-Paquette, D., & Julien, H. (2005). How human information behaviour researchers use each other’s work: A basic citation analysis study. Information Research, 10(2).

McKechnie, L. E., Julien, H., Genuis, S. K. & Oliphant, T. (2008). Communicating research findings to library and information science practitioners: A study of ISIC papers from 1996 to 2000. Information Research, 13(4), paper 375. Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper375.html

Nguyen, L. C., & Hider, P. (2018). Narrowing the gap between LIS research and practice in Australia. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2018.1430412

Pettigrew, K. E., & McKechnie, L. (2001). The use of theory in information science research. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(1), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/1532-2890(2000)52:1<62::AID-ASI1061>3.0.CO;2-J

Pinfield, S., Wakeling, S., Bawden, D., and Robinson, L. (2020). Open access in theory and practice: The theory-practice relationship and openness. Taylor & Francis.

Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching information seeking in the context of “way of life.” Library & Information Science Research, 17(3), 259–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(95)90048-9

Schroeder, R., and Hollister, C. V. (2014). Librarians’ views on critical theories and critical practices. Behavioral & Social Sciences Librarian, 33(2), 91-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2014.912104

Simon, H.A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99-118. doi:10.2307/1884852

Taylor, R. S. (1968). Question-negotiation and information-seeking in libraries. College and Research Libraries, 29, 178–194. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.3.251

Tsangaridou, N., & O’Sullivan, M. (1997). The role of reflection in shaping physical education teachers’ educational values and practices. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 17(1), 2-25.

VanScoy, A., Julien, H., & Harding, A. (2022). “Like putting broccoli in a quiche”: Instructors talk about incorporating theory into reference courses. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 63(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis-2021-0022

VanScoy, A., Julien, H. and Harding, A. (2023). Information behavior in reference and information services professional education: Survey and project synthesis. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis-2023-0012

Wakeling, S., Pinfield, S., & Bawden, D. (2019). The use of theory in research relating to open access: Practitioner perspectives. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 56(1), 788-789. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.177

Wilson, T. D. (1981). On user studies and information needs. Journal of Documentation, 37(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026702

Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM000000000714