Vol. 10 No. 3, April 2005

| Vol. 10 No. 3, April 2005 | ||||

| Robert Vaagan Oslo University College Postboks 4 St. Olavs plass 0130 Oslo, Norway |

and | Wallace Koehler Valdosta State University 1500 N Patterson St. Valdosta GA 31698, USA |

Introduction. In 1999-2000, a Norwegian youth cracked a DVD-access code and published a decryption program on the Internet. He was sued by the US DVD Copy Control Association (DVD-CCA) and the Norwegian Motion Picture Association (MAP), allies of the US Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), arrested by Norwegian police and charged with data crime. Two Norwegian court rulings in 2003 unanimously ruled that the program did not amount to a breach of Norwegian law, and he was fully acquitted. In the US, there have been related cases, some with other outcomes.

Method. Based on a theoretical framework developed by Zwass, the paper discusses these court rulings and the wider issues of intellectual property rights versus public access rights.

Analysis. The DVD-Jon case illustrates that intellectual property rights can conflict with public access rights, as the struggle between proprietary software and public domain software, as well as the SPARC and Open Archives Initiative reflect.

Results. An assessment of the DVD-Jon case based on the Zwass framework does not give a clear information ethics answer. The analysis depends on whether one ascribes to consequentialist (e.g., utilitarian) or deontological reflection, and also which side of the digital gap is to be accorded most weight.

Conclusion. While copyright interests are being legally strengthened, there may be ethically-grounded access rights that outweigh property rights.

From September 1999 to January 2000, a then fifteen-year old Norwegian hacker ('DVD-Jon'), acting with others, developed a data program that circumvented the Content Scrambling protection on DVDs and made it possible to view the DVDs with the open source Linux operating system. He then published his DeCSS decryption program on his Website, allowing others to download and use it. DeCSS removes the copy bar (CSS - Content Scrambling System) in DVDs and stores a copy of the film on the hard disk. The copy bar is licensed by DVD Copy Control Association Incorporated for the protection of DVD films produced by Motion Pictures Association members. In January 2000 the plaintiffs, the US DVD Copy Control Association (DVD-CCA) and the Norwegian Motion Picture Association (MAP), allies of the US Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), filed charges in Norway against the hacker. Yet, three years later, in January 2003, he was fully acquitted of all charges in the Oslo municipal court. The ruling was appealed to Borgarting appellate court, which in December 2003 upheld the lower court ruling. Both rulings were unanimous. Both courts acknowledged that DeCSS can be used for the production of pirate copies, but neither court found it proven that this was the defendant's intent in developing the program. Moreover, neither court found it proven that others had used the DeCSS program on illegally procured DVD-films. The prosecution did not appeal to the Norwegian Supreme Court. The rulings are seen as a clear victory for the open source movement, and have elevated DVD-Jon from the ordinary hacker ranks of white and black hats (Schell & Lodge 2002) into becoming a hero of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Open Source Initiative.

In the USA, where the controversial Digital Millenium Copyright Act (DMCA) was introduced in 1998 (Samuelson 2003; Lessig 2004: 156), there have been related cases, some with other outcomes. The California Supreme Court in August 2003 (DVD Copy Control Association v. Bunner 2003) overruled previous lower court decisions by ruling that stopping the publication of the DVD copy code DeCSS does not conflict with the freedom of expression. The ruling was a triumph for the DVD Copy Control Association (DVDCCA) which has sued dozens of Websites for publishing DeCSS (Eschenfelder & Desai 2004).

As a first example, in United States v. Thomas, a US Appellate Court (1996) held that a couple who operated a computer bulletin board system in California could be successfully prosecuted in a federal court in Memphis, Tennessee. The case depended upon the community standard for the definition of obscenity. Community standards in western Tennessee were determined to differ from those in California. Prosecutors determined that Tennessee would provide a better venue than California.

Second and more on point for the DVD-Jon case was the decision to arrest and prosecute Dmitry Sklyarov, a Russian scientist for code cracking under the DCMA. His Russian employer, ElcomSoft was also charged. Sklyarov had developed and published in Russia the program Advanced eBook Processor, which cracked Adobe's eBook Reader. He was arrested in the United States as he was to address the Defcon-9 conference in Las Vegas in 2001 (see U.S. v. ElcomSoft & Sklyarov 2002). In the end Sklyarov and ElcomSoft were found not guilty by the jury.

The Norwegian and California rulings are interesting both legally and ethically and raise a host of questions. While the law is preoccupied with what is legal, ethics is primarily concerned with legitimacy. Although the law and ethics often go hand-in-hand, civil disobedience is a reminder that this is not always the case. DVD-Jon argued throughout that he was defending a legitimate cause, and the Norwegian court rulings served to back this interpretation. Do ethical opinions differ as much as legal opinions on the DVD-Jon case? Can all kinds of digital information and knowledge be considered intellectual property? Is there a clear borderline between public domain and proprietary software? How can one distinguish between the public's right to access and the ownership rights of authors and producers with respect to intellectual property? Zwass (2003) discusses information ethics issues in terms of four main domains: privacy, accuracy, property and access. Clearly, the DVD-Jon case is about property, as the California Supreme Court ruling shows, but the Norwegian court rulings (and the rulings of lower courts in California) also suggest that access, and freedom of expression, are at stake (Vaagan 2004).

The two Norwegian court rulings have been made available in English by Electronic Frontier Norway, and, therefore, we quote only the abstracts:

Oslo Municipal Court on 7 January, 2003 reached the following verdict:

Criminal law. The penal code section 145 second paragraph cf third and fourth paragraph. A nineteen-year old man was indicted for violation of the penal code section 145 second paragraph cf third and fourth paragraph. He had developed a computer program making it possible to view DVD movies without licensed playing equipment. The court found first that access to movies legally purchased was not unlawful with respect to the penal code section 145 second paragraph even if the movies were viewed in a different way than presumed by the producer. Second, the court found that disclosure of encryption keys by itself did not constitute unauthorised access to data. The indicted could neither be convicted for contributory crime to the possible unauthorised access by others to DVD moves because the program also had a legal application.

Borgarting appellate court on 22 December, 2003 upheld the lower court ruling:

A young person had in 1999 with others co-operated to the development of a program that circumvented Content Scrambling System for DVDs, and posted this on the Net. He had programmed a user interface which made the program available also for persons without any special knowledge of information technology. The appellate court found, as the first instance court, that the development of the program was not illegal. The action was not found to be an infringement of the provisions of the copyright act. Therefore, access could not be qualified as 'unauthorised' according to the criminal code sect. 145, second paragraph. The appeal of Økokrim was therefore rejected.

As stated, the prosecution did not appeal to the Norwegian Supreme Court, so the last ruling is seen as a resounding legal victory for the defendant. Norwegian consumer groups like Electronic Frontier Norway were delighted. Having been ethically convinced throughout of the legitimacy of their cause, they now have legal backing—at least in Norway. DVD-Jon and like-minded spirits, encouraged by the rulings, see themselves, and are seen, as crusaders of the open source movement. They view software as a common good to be shared, not to be sold for profit. In Norwegian librarianship, where free access to information is the overall most frequently quoted professional value (Vaagan & Holm 2004), the verdicts are welcome. In late 2003 DVD-Jon also cracked a copy bar on the Apple iTunes Music Store, allowing users to play barred music files in the ACC-format in Linux. This was refined into a program called PlayFair, causing Apple to take legal action against Websites and servers using the program. In April 2004, encouraged by the rulings, he published on his Website a new version of the same program called DeDRMS. Hackers and proprietary software developers are spurring each other on, in a spiral of technological creativity. In this sense at least, they are useful to one another.

Could DVD-Jon be tried in the United States? The United States represents the largest market for, and the largest producer of, intellectual property in the world. The United States has also manifested a willingness to extend its competence beyond state and national boundaries to enforce its intellectual property jurisprudence interpretation into other jurisdictions (Lessig 2004).

As a first example, in United States v. Thomas (1996), the courts held that a couple who operated a computer bulletin board system in California could be successfully prosecuted in a federal court in Memphis, Tennessee. The case depended upon the community standard for the definition of obscenity. Community standards in western Tennessee were determined to differ from those in California. Prosecutors determined that Tennessee would provide a better venue than California.

Second, and more pertinent to the DVD-Jon case, was the decision to arrest and prosecute the Russian scientist Dmitry Sklyarov for code cracking in violation of the DCMA. His Russian employer, ElcomSoft was also charged. Sklyarov had developed and published in Russia the program Advanced eBook Processor that cracked Adobe's eBook Reader. He was arrested in the United States as he was to address the Defcon-9 conference in Las Vegas in 2001 (see United States v. ElcomSoft 2002). In the end Sklyarov and ElcomSoft were found not guilty by the jury.

Under existing USA law, DVD-Jon might suffer the same fate as did Sklyarov. Were he to have entered USA jurisdiction, he might have been arrested and prosecuted. Would he have received the same finding as in United States v. ElcomSoft is problematic and speculative.

As stated, the law and ethics sometimes come up with different views. As Frické et al. (2000: 470) point out in their analysis of the ethical basis of the Library Bill of Rights, laws can be unethical or wrong: slavery in America and the Holocaust in Nazi-Germany are two examples. Today many would also include in this category religious laws such as Islamic sharia law. Abortion or embryo-based research are legally and ethically divisive issues in many countries.

The intellectual property rights of software developers, in most cases, do not conflict with public access rights. The protection of intellectual property through ordinary patents or trademarks can even be conceived as a social contract under which society protects the owners' rights while products are marketed to the public at a price. Sometimes patents or trademarks are viewed as insufficient and are reinforced by supplementary protective measures such as copy bars. Yet this price and/or the supplementary measures can be interpreted as unethical. The World Trade Organization TRIPS agreement (trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights) as late as August 2003 (some twenty years after AIDS first appeared) apparently resolved the long-standing deadlock over intellectual property protection and public health. Governments finally agreed on legal changes to facilitate poorer countries' import of cheaper generics made under compulsory licensing if they are unable to manufacture the medicines themselves. Many see, for example, article 27.3b of the WTO/TRIPS agreement (1994) which deals with patentability or non-patentability of plant and animal inventions, and the protection of plant varieties, as profoundly unjust and unethical. Lessig (2004), inspired by Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation, argues that most of the media industry has developed historically thanks to piracy, and that big media exploit technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity. In our context we will concentrate on the following issue: How can one ethically distinguish between the public's right to access and the ownership rights of authors and producers with respect to intellectual property?

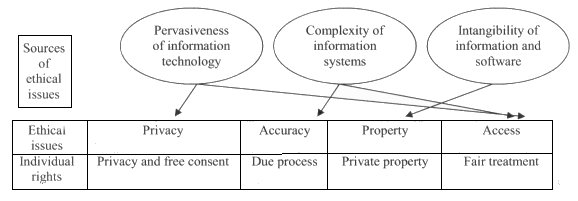

Four main ethical issues with respect to information systems are often focussed on: privacy, accuracy, property and access. These four issues can in turn be traced back to three main sources: 1) the pervasive role and capacity of systems for collecting, storing and retrieving information, 2) information technology complexity and 3) the intangible nature of information and digital goods, such as digitized music or software (Zwass 2003: 1056):

In this framework, the DVD-Jon case clearly involves the ethical issues of property and access, linked with the corresponding individual rights of private property and fair treatment. Translated to a courtroom setting, where, as in this case, we have a plaintiff versus a defendant, we need to clarify whose private property and fair treatment of whom.

Before proceeding it should be added that concentrating on property and access does not mean that the other two ethical issues of privacy and accuracy, linked with the rights of privacy and free consent as well as with due process, are not important or cannot be related to the DVD-Jon case. As discussed elsewhere (Vaagan 2004), the debate surrounding the Total Awareness Act and the differences between privacy standards in the USA and Europe show that these two ethical issues are among the most controversial electronic information age issues following September 11, 2001. Privacy and accuracy, to some extent at least, can also be related to the case at hand; for example, if one views the production and dissemination of pirate copies as part of freedom of expression, or if one argues as Lessig (2004) does, that free culture and consumer interests in the USA are being suppressed by strong, protectionist big-business media interests interacting with the US government and are resulting in laws like the DMCA.

The World Intellectual Property Organization solicits studies in an expanding field of activities ranging from the Internet, health care, all aspects of science and technology, literature and the arts, patent systems and access to drug care, genetic resources, traditional knowledge and folklore. Intellectual property such as licensed software is clearly protected by several legal mechanisms such as patents, copyright (among the most important forms of intellectual property) or trade secrets. Faced by digital piracy and illicit copying, proprietary software producers in addition frequently restrict or limit use, for example, by anti-copying measures such as copy bars.

Some do not accept restrictions on the free utilization of intellectual property, e.g., in countries where piracy is openly justified or covertly condoned, sometimes arguing that poverty prevents their paying high prices for imported materials, or even that it represents redress for colonial exploitation (Marrett 2003). In the words of Lessig (2004: 64), 'The physics of piracy of the intangible are different from the physics of the tangible'. Are they in the wrong, ethically speaking? This is a very fundamental point but is beyond our present scope. It serves to illustrate, however, that there are a number of unresolved problems in the borderlands of law and ethics. In the following we will concentrate ethical reflections with regard to legally procured and licit material such as open archives and open source material.

The difficult balancing of these interests is well reflected in the reactions by many consumer groups to the new European Union Directive for the Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights (2004), (IPR Directive) which became EU law in April 2004. The protests from consumer groups such as the Irish Free Software Organization pointed to the directive's alleged extreme provisions and harsh treatment of ordinary consumers for even non-commercial or accidental infringements. The IPR Directive means that the reverse engineering of software products in order to produce competing, compatible products would be subject to sanctions. It is feared that this would greatly affect the free software movement and the growing use of open source software.

Access may be interpreted restrictively to refer only to the open versus closed access of users to library materials. Here the trend has been from closed to open access almost everywhere except in archival and research collections (see below) or the library systems of totalitarian states (Feather & Sturges 2003: 468). Yet, in the context of information ethics, access has a far wider application than libraries. Internationally, the digital divide among and within, countries is probably the most obvious aspect of the access issue. Some see the digital divide as one of the most serious ethical problems internationally in the information age (Vaagan 2002: 1).

Factors that influence the digital divide are socio-economic status (income, education), gender, life stage and geography. The Computer Industry Almanac estimates that the worldwide number of Internet users will top one billion in mid-2005, and reports that at the end of 2004, as few as fifteen countries accounted for 71% of the global Internet user population. The USA alone accounted for 185 million Internet users while the countries next on the list are as follows: China (99), Japan (78), Germany (41), India (37), UK (33), South Korea (32), Italy (25.5), France (25.5), Brazil (22), Russia (21), Canada (20), Mexico (13), Spain (13) Australia (13). There is little Internet user growth in developed countries, and over the next five-year period many users will switch to high-speed broadband connections and supplement Internet use with Smartphone and mobile Internet devices. In developing countries, especially China, there is considerable growth potential for Internet use (Computer Industry Almanac 2005). Yet the digital gap exists not only among but also within countries: in relation to the population base within each country, a former study had shown that within the European Union, the countries with the highest and lowest proportions of online users were Sweden (68%, September 2002) and Lithuania (8%, October 2001) (NUA Internet Surveys 2005).

A specific aspect of access noted above which particularly worries the academic and research community is access to electronic journals. Initiatives like the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC) and The Open Archives Initiative reflect the academic community's concern with growing restrictions to access. Strained library budgets and the spiralling costs of electronic journals restrict access and may contribute to the digital divide. Currently the Directory of Open Access Journals numbers only some 1400 journals, which is modest compared to the Thomson group's approximately 8,000 journals indexed by the Web of Science.

Related to this is the struggle between proprietary and public domain software, illustrated, for example, by the Microsoft-Linux competition. The California Performance Review envisages cost-cutting measures of thirty-two billion US dollars over the next five years, partly by switching from proprietary software and traditional telephone systems to open-source software and voice over Internet Protocol telephony (Lemos 2004). Also in Norway we see this development. The second-largest city, Bergen, as a cost-saving measure, has recently switched from Microsoft to Linux. Norway's largest daily Aftenposten reported on 15 June, 2004 that this affects the city's 15,000 administrative staff, 35,000 school pupils and almost 100 schools. The appeal of freeware, public domain software is obvious to poorer countries. To meet this challenge Microsoft is differentiating its pricing and marketing strategy and offering a cheap version of Windows XP in Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia. As may be expected, market share estimates vary considerably (Petreley 2003), as do future prospects.

There are several different philosophical approaches to perspectives on ethics and information ethics. On the one hand, information ethics is described in metaphysical, abstract terms. Floridi (2004) and Capurro (2000) address computer science and ethics and information ethics respectively in terms of underlying ontologies. It is sometimes described in more specific terms. Smith (2000) would describe information ethics as applied ethics with both broad and specific applications. Koehler et al. (2000) and Koehler and Pemberton (2000) have sought to identify the sources of and practices of information ethics by examining actual practice as reported by information professionals or as documented in professional codes of ethics.

Froehlich (2003) distinguishes between two main perspectives on information ethics. Whereas the first treats ethics both as a descriptive and emancipatory theory, the second views ethics either as a metadiscipline or as a kind of applied domain. Particularly as a descriptive theory where it analyses the power structures of different societies and traditions, and as an emancipatory theory where it is contrasted with established moral and legal customs, norms and practices, information ethics is a potent tool to assess the implications of the DVD-Jon case.

Zwass (2003) distinguishes between consequentialist (e.g., utilitarian) and deontological reflection. Consequentialist ethical thought advocates that one selects the action with the best possible consequences. Utilitarian theory holds that our chosen action must produce the greatest overall good for the maximum number of people. On a capita basis and seen against the background of the digital divide among nations, it would seem that crusaders like DVD-Jon and the open source movement are ethically justified from a utilitarian perspective. By contrast, utilitarian theory would argue that the interests of the minority of proprietary software developers and vendors must be sacrificed for the larger good of public access. But from another ethical standpoint, deontological ethical theory argues that we must do what is right. Our actions are models of behaviour, and we must act as such. The problem is that both DVD-Jon and Bill Gates could argue in this way.

The open archives and open source movements are consistent with the IFLA core value of free access to information, which are fully subscribed to by most professional library associations. Yet as has been argued elsewhere (Vaagan 2004), free access to information and the freedom of expression are ideals which under certain conditions, e.g., emergencies or war, can be legally proscribed even in democratic societies. Zwass (2003) argues that major individual rights in democratic societies are the right to life and safety, the right of free consent, right to private property, right of free speech and fair treatment. Much here depends on who we claim these rights for. If these are those on the other side of the digital divide—the vast majority of the world's present population of 6.4 billion—who are still not online, it would seem that both consequentialist-utilitarian and deontological ethical theory condone the open archives and open source movement.

How are we to assess ethically those situations where intellectual property rights conflict with public access rights with regard to digital products such as in the DVD-Jon case? As we have seen the legal system provides different answers, and is influenced by national legislation, treaties and customs. Also from an ethical point of view, assessments vary, depending on consequentialist (utilitarian) and deontological perspectives and not the least on which side of the digital divide one identifies with (Lester and Koehler 2003: Chapter 11).

The DVD-Jon case, as well as other prominent and related cases, represent the nexus between ethics and more specifically information ethics and law. Consider hacking. It was once thought of as a sort of romantic quixotic pursuit (Levy 1984; Sterling 1992), but no longer. We can differentiate between benign and malicious hackers (Parker 1998: 160-61). A benign hacker is a hobbyist, engaged in penetrating other people's computers and computer systems for the sport of it. The malicious hacker penetrates those systems for nefarious or criminal intent. Is benign hacking the realm of information ethics while malicious hacking falls within the jurisdiction of the law? Who decides whether a given instance is benign or malicious? Are activities that are initiated in one country actionable in another?

The threat to information systems and our resultant vulnerabilities have become the subject of academic and popular literature (e.g., Yourdon 2000). How do societies protect themselves in light of these threats, real or perceived? One answer is to build more complex systems to respond to those threats or to mitigate or shift the risks. Some of these responses are essentially technological in nature, others are social. For example, companies or governments can seek to erect impenetrable firewalls around their ICT systems—a technical response. Governments can legislate draconian punishments for those who engage in information crimes—a social response. Professional organizations and educational institutions can inculcate a sense of legitimate practice and ethics—an institutional response. We have also witnessed a shift in the way intellectual property is provided in the marketplace, in part to protect the economic interests of the owners of copyright. Anyone acquiring software buys a license to use that software rather than its outright purchase. The relationship between user and supplier and their respective rights is changing.

In the end, we may come down to a conflict among values. To repeat a phrase from the introduction:

Clearly, the DVD-Jon case is about property, as the California Supreme Court ruling shows, but the Norwegian court rulings (and the rulings of lower courts in California) also suggest that access, and freedom of expression, are at stake ( Vaagan 2004).

Where there are conflicts between property on the one hand and access and freedom of expression on the other, ethical and legal considerations must be weighed. As shown by Lessig (2004), how we define property, access, and freedom of expression have cultural, political, legal, professional, and technical determinants. As any of the underlying determinants change, inevitably how we interpret legal and ethical precepts must necessarily change as well. To square this with a deontological approach, one may argue that the performance of right can be changed as what is defined as what is right is changed. Similarly, the utilitarianist might recognize that the most good for the greater population also may undergo redefinition.

None of this answers the fundamental questions raised by the DVD-Jon case. We do recognize that in law the rights of the copyright holder are being reinforced. At the same time, there is a growing recognition that there may be access rights that supersede property rights. It remains to be seen to what extent this growing recognition in a globalized economy will affect copyright holder rights.

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions and suggestions of the anonymous referees

| Find other papers on this subject. |

| ||

© the author, 2005. Last updated: 9 April, 2005 |