Vol. 11 No. 3, April 2006

| Vol. 11 No. 3, April 2006 | ||||

Introduction. The invisibility of research on information needs from the East and Central Europe in the West suggested an exploration of the published research output from Lithuania and Russia from 1965 to 2003.

Method. The data were collected from the abstracting journal Informatika-59. The publications were retrieved from Lithuanian and Russian libraries or the Internet.

Analysis. The texts and, in cases when full-texts were not available, the abstracts were used for qualitative analysis assessing the relevance, content, concepts used and their change over time. Comparison with the Western (English language or Anglo-American) literature was carried out.

Results. The development of the concept of information user needs in Russia and Lithuania is followed through several decades as well as the understanding of its origins, structure and typologies. The parallel concepts and similar ideas are traced in the Western information behaviour literature. A context of related research (reading studies and information literacy) is revealed.

Conclusions. Despite the isolation of two bodies of research (Western and East European) in the area of information needs the common development and similarities in the understanding of the basic concept of information need, its origin and structure as well as typologies are revealed. Basic differences lie in understanding the contexts of the formation of information needs, their influence and, consequently, attention to the roles of contexts in research. It also seems that the everyday, non-work related information needs are totally excluded from the horizons of Russian researchers.

Communication between library and information studies researchers in the East and Central Europe and the Western world is still in the embryonic stage, although practitioners in the field are participating more and more in various exchanges, organizing common events, and developing cooperative projects and programmes. But the increasing exchange, in general, has not affected the patterns of participation from various regions in the research conferences, which are the major forums for exchange of ideas, though the European Union (EU) is supporting some common research projects such as CALIMERA.

However, since May 2004 there has been a significant increase in the number of articles from the new EU members (as well as Russia) in the West European research and professional journals. Previously, the analysis of bibliographic data usually revealed the lack of scholarly communication between the regions (for the sake of simplicity, we shall label them East European or 'Eastern' vs. 'Western' or Anglo-American and Nordic). Previously, the increasing interaction was visible in the accession countries in the number of translated books and articles, articles in English, German or other languages by Western colleagues published in local journals, which were referenced by local authors relatively often, even before the process of accession to the European Union began.

The Western world scholarly journals in library and information studies also seem to be more interested in the output of the colleagues from the new EU members. If, in 2003, I could comment on almost every scholarly publication (about a dozen of them) found after a diligent search in relevant databases, at the beginning of 2006 the number of publications was at least tenfold. Most of the articles appeared in professional journals, but the number of research articles also was significantly greater. A search on the Web of Science (1986-2005) for articles by major Russian writers in library and information studies field or relevant cited items, yielded the articles from one of leading Russian information science journals Naucho-tekhnicheskaja informatsiya which was included in the database. This allowed me to get the citation data for the Russian authors. I also have found several Lithuanian authors cited in foreign publications (German, American, Russian, etc.).

The difference in the publishing and research traditions, as well as alien ideological contexts of research and theoretical development seem to be additional barriers to the language, geographical, or economic difficulties that impede the exchange. The increasing contacts are resulting in change, but it is slow.

The absence of researchers from the east and Central Europe participating in the Information Seeking In Context (ISIC) series of conferences, other than Aiki Tibar from Estonia (Tibar 2000 ), suggested the idea of exploring published research output in the field of information seeking in Lithuania and Russia. I limited the paper to the literature on information needs from 1965 (the year when, according to general agreement, the concept of information needs appeared in Russia) to 2003. It includes statistical data on publications, analysis of contents, object of research, and prevalent concepts. There is also a limited comparison with the development of the concepts of information needs in the West.

The terms information needs and information users and use are quite familiar to the communities of library and information practitioners as well as to library and information studies researchers in Russia and Lithuania. However, it is not clear if the objects of study, theoretical approaches, and methods are comparable and how different or similar they are from those used in the Western tradition. My interest in this was raised by reviewing of the proceedings of ISIC. I was curious as to whether the studies related to the field of information behaviour in the West correspond with those carried out in the research space to which I belong. My own area of interest in information users (especially their needs) related mainly to the studies of bibliographic services and information management (e.g., Janonis & Macevičiūtė 1999). I have spent some time searching for published research and reviews, collecting the evidence suitable for comparison, and studying the issue. I am sure I have not got to the bottom of the problem, but at least I have some data that allows me to speculate about some aspects of it.

If we look in general at East European research within the whole body of research in information-related behaviour carried out within the borders of the previous Soviet Union and socialist block countries we can distinguish several broad areas:

Readerhip studies in Russia have a long-standing tradition and have been developed into an independent discipline by Rubakin (1895, 1929). Since then, libraries (their research and methodology departments) as well as library and information studies schools and other higher education institutions have conducted research into various aspects of reading. A series of huge projects was conducted by the main Russian libraries between 1960 and 1980 looking into various aspects of libraries, books and reading in large and medium-sized cities (Chitatel'skiye interesy 1966), small towns (Kniga i chteniye 1973), villages (Kniga i chteniye 1978), investigating reading of specialists (Specialist 1971), the Soviet reading public (Sovietskij chitatel' 1968), not to speak of smaller research projects. The trend continued after 1990: book and reading as a sociological issue (Stel'makh 1990), in the time of cultural shift (Stel'makh 1998), at the end of 20th century (Butenko 1997), reading in the life of teenagers ( Viatkina 1996), students (Biriukov 1999), blind persons ( Kovalenko 1991), etc. Every national library in the Soviet republics also conducted similar research. Despite rather strict ideological limitations an impressive amount of quantitative and qualitative data was collected. It revealed the reading habits of various social groups, the influence of teachers and librarians on reading skills, relations between reading and development of the imagination, various types of interests, knowledge, and skills, and placed the book in the context of other media. This research was, and is, important from the methodological point of view as it usually set the standards for valid statistical, sociological, psychological, and other research methods. One may guess that this research direction might be closest to Western research on information users' behaviour from this point of view.

Another intensive and vast research activity in information literacy issues can be and usually is missed by Westerners. The term for information literacy in Russian and, subsequently, in the languages of neighbouring countries is 'informatsionnaja kul'tura' or, literally, 'information culture'. This direction springs from the concern with literacy and reading skills, but during fifty years and especially the latest decade, reflects on a wider range of skills required for 'cultural development of an individual'. However, the translation 'information culture' effectively loses these publications in Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA), other than several that have been located correctly under 'information literacy'. Thus, the 'language barrier', limits access to a growing flow of Eastern literature on user education and related topics.

The third research direction, that of information needs, is the youngest and the first publications appeared approximately forty years ago. In 1965 Mikhailov, et al. discussed the needs of scientists in relation to science information resources. That was almost a decade later than Bernal's famous conference paper (1959). Bliumenau states that the 'historical period of research into information needs is characterised by ups and downs and among hundreds and hundreds of publications very few investigated this complex problem in depth...' Bliumenau (1997: 38)

Actually, I have the impression that in talking about hundreds and hundreds of publications Bliumenau is exaggerating. In the catalogue of the abstracts of doctoral dissertations defended in Soviet Union and Russia from 1987 to 2002, 310 dissertations within the library and information science field are registered. Only six can be related to information needs or information behaviour. Another three were defended in 2003-2005. There were also approximately twenty works investigating library and information service, information provision and support to various groups of users. To some extent users' needs may also be discussed in these dissertations. Do these figures point to 'hundreds of research articles'?

The basic source of relevant publications was the abstracts journal Informatika—59 published by VINITI for publications in Russian, and the national bibliography of articles for Lithuanian papers. The database of Informkul'tura as well as LISA and Library Literature & Information Science databases were used for control purposes. Some major Russian and Lithuanian library and information studies journals (Informatsionnye resursy Rosii, Nauchno-tekhnicheskaya informatsiya, Nauchnye i tekhnicheskiye biblioteki, Informacijos mokslai, Knygotyra) can be found as a full-text free resource on the Web. Usually, articles published from 1996 or 1997 can be retrieved from these sites. Some others (Bibliotekovedenije, Mir bibliografii) publish only contents pages. These sources were also used to fill in the gaps. The reference lists were studied to fill in the gaps for the earlier period (before 1996) and to identify the most influential authors and publications. Web of Science was used to find partial citation data.

The abstracting journal Informatika-59 registers the abstracts of Russian and foreign articles, books, dissertations, conference materials, etc. It has a separate section, 'Information users' needs and information users', which was the major source of required information.

The publications were retrieved from Lithuanian and Russian libraries or the Internet (for the latest years). In cases when it was impossible to get a full-text (e.g., some old conference material or small print-run publications) the abstracts were used to assess the relevance, content, and research details.

The content of publications was studied to find out the definitions, structures, and models of information needs and to extract the data about research methods. The discussion part is devoted to the comparison of the development of the concept 'information needs' in the Anglo-American and Russian-Lithuanian tradition.

Reviews of literature of existing research on information needs were done by several authors in different years (Voverienė 1996, Krūminaitė 1990, Bliumenau 1986). From all of them one can see that the actual number of publications was not enormous. According to the estimates from 1965 to 2003, 308 items discussing information needs appeared in Russia and sixty-eight in Lithuania. Since then, in the mainstream journals and publishing houses, eight more items were published in Russia and four in Lithuania. The dynamics definitely show variation over the years.

The highest peaks of publishing are observed in 1990 and 1992. A close look revealed that in 1990 a large collection of articles on research of information needs in fundamental science was published by the Novosibirsk department of the Academy of Science (Soboleva & Chistiakov 1990). It included thirteen articles. In 1992 another collection on information needs in pedagogic and public education was published in Moscow (Informatsionnye potrebnosti 1992). The other peaks are mainly related to conferences that included papers on information needs.

The main body of publications consists of conference abstracts or papers (c. 35%). Dissertations and monographs are quite rare (eight appeared in Lithuania during the period and about twenty-two in Russia). The major periodicals publishing articles on information needs are Naucho-tekhnicheskaja informatsiya. Series 1 and 2, Nauchnye i tekhnicheskye biblioteki, and Knygotyra/Informacijos mokslai.

Occasional collections of research papers published by the institutions of higher education (Moscow State University of Culture und Arts, St. Petersburg University of Culture, etc.) also include a significant number of articles on information needs.

According to the Web of Science, authors who published most on the topic of information needs were Shekhurin (8 publications), Bernshtein (5), Voverienė (4), Sokolov (4), Bliumenau (4), and Kogotkov (3). They were also most cited by others investigating this subject. Our own files include also other productive authors: Kancleris (7), Chiornyj (5), Atkočiūnienė (4), Zinkevičienė (4), Janulevičienė (3), Kalinina (3), Golovanov (3), and Soboleva (3).

The research on information needs, especially in Russia, depends, on one hand, on the general concept of the human being (as a species) and, on the other hand, on the specific definition of an information user. Both definitions prevalent within Russian information science have been changing slightly over time and in the works of different authors, but their essence remains basically intact.

Under the prevailing concept, a human being is regarded as a complex psycho-physiological system formed and acting within complex social system. According to Artamonov:

From the point of view of information science a human being is a complex information enterprise, processing incoming information and producing information for other human beings. Development and even survival of this system is determined not only by the amount of incoming information for processing, but also by consumption of produced information. (Artamonov 1998: 29)

Different authors mention various mechanisms for processing information in this system, but they invariably turn to one or another physiological function of brain. Sliadneva refers to a human being as 'a highly effective, self-educating system, which is flexibly adapting to the changing environment... via the brain's homeostasis.' (Sliadneva 1999: 33). Yanovsky sees memory as a basic mechanism of control not only over the incoming and outcoming information but also over the behaviour of an individual (Yanovskyi 2000: 7).

An information user in Russian information science is not only an individual. A collective (a group, an organization, a social class, etc.) or the inhabitants of a certain territory (a 'territorial user') is also an information user. The main feature of any information user is a goal (task, function, etc.) of work or socially significant activity that has to be reached (solved, performed, etc.) with the help of information (among other means) (Kancleris 1967, Chernen'kij 1998). Therefore, these types of collective and territorial users can have information needs (see Leonchikov 1999).

According to Sokolov (1996), an information user (or a carrier of communication need, in his terms) may be a biological entity, an individual human being, a group of people, or a society. The needs of an individual and of a social group or a community will differ in content, but their types will be analogous.

During the first decade of the research on information needs the authors were concerned with separation of readers' interests and needs for special information (or information needs). Over time various terms were used in different works without any significant difference in meaning (need for library and bibliographic resources, documentary needs, need for reading, communication needs) but 'information need' was the most widespread.

In 1967 information need was defined as 'an expression of the deficit of concrete information by an individual (collective or territorial) user solving a certain scientific or technical problem' (Kancleris 1967: 2). The narrowness of definition was evident and soon it was reformulated as follows: 'Information need is a necessity to acquire information about (or from) the surrounding environment' (Rakipov 1969: 3). Most authors treated information need as a lack, deficit, gap, or difference between the knowledge required and knowledge possessed.

The definition of the information need was closely related to its nature and origin. When and how information need emerges was a subject of many discussions. During the 1960s the main outcome of the discussions was sorting out the confusion between needs, interests, requests, and queries. Many authors were looking actually into the process of formulation and expression of information need, rather than into its occurrence. Shekhurin had a great influence on the later developments in the field of information needs. According to his theory, information need emerges under the influence of objective and subjective factors. The objective factors are the goals of the development of the society, tasks of various economic sectors, directions of development of science and technology, etc. These objective factors generate 'objective information needs' of society and social groups. On the other hand, the actual problems are solved by people - scientists and specialists - who have to find the best solutions. Their psychological features, knowledge, values, etc. are the subjective factors generating subjective needs for information. Objective and subjective information needs form a dialectic unity and can be separated only conditionally (Shekhurin 1968, 1970).

During later years the notion of objective information need was criticised by the representatives of the 'psychological school', especially by Bliumenau (1986), who stressed the role of individual expression and subjective perception in the process of originating information needs. According to his concept, information need is subjective and based on an objective need for cognition resting on unconditional reflex for orientation. Information need is a subjective reaction of the individual that provides a mental image of dissonance between required and acquired knowledge (Bliumenau 1997).

Kogotkov (1979, 1986) developed and expressed this concept in the model shown in Figure 2:

According to the author, information need includes the feeling of lacking something and wishing to fill the gap. Besides that, some picture of the needed information also has to be present. In 2003 he defined information need as 'a necessary relation of a subject to information reflected in his consciousness and psyche' (Kogotkov 2003: 48). The representatives of this school saw information need as a result of human activity, which is the starting point of satisfying the cognition needs and, therefore, activity is both a starting point and a way of satisfying information need (Shcherbitskij 1983: 47). All activity of living organizms and especially human activity always generate need for information about the changing environment and the conditions of the tasks performed. The character of the human activity defines the character of information needs (Motul'skij 2001).

Finally, Sokolov (1996, 2002) has rejected the idea of information need and suggested that it is only a separate case of a communication need, which he defines as a functional quality of a subject to react to a dissonance between the current and the normal state of consciousness by seeking meanings in knowledge, emotions, and interactions.

Information need was recognised as a complex phenomenon generated by complicated environments and peoples' minds. The structure of information need was one of the topics discussed in various forums.

The earliest structures of information needs were related to problem solving (Figure 3):

Other authors suggested a more universal model (Figure 4), which was summarised by Kancleris. It included undefined needs, formed needs, and needs that have to be satisfied. Undefined needs occur at the beginning of the work and require intuitive or experience-based approaches. In the course of work the needs are consolidated and can be expressed more precisely. The needs expressed in the forms of request are handed over to information services or libraries to get answers. The author in this case uses the notion of a collective information need experienced by a group of specialists

This structure remains more or less stable till present. Recently, Maksimov and Zabegaeva (2001) have defined similar four levels of information needs: internal, concious, formalised, and adapted to the information search language.

Once again, among the most influential structures of information need we find one suggested by Shekhurin (1968, 1970). In this structure (Figure 5) he tries to unify the needs of various levels and to explain the relations between these levels.

According to the author, the General Information Need is a need of a person or any social entity. It is an abstraction of the characteristics of all lower level needs (societal, group, and individual). It is not a sum of these lower level needs but includes the basic core that sets information need apart from all other needs. Societal and Group needs are influenced by Individual Needs and are expressed through individual needs

Five years later Korshunov used the concept of a general information need to develop his functions of bibliographic information that were related to the general information (or documentary) needs: to locate a document, to receive a message about the existence of a document, and to evaluate a document (Korshunov 1975).

Kogotkov (1986) also tried to establish a hierarchical structure of information needs but on a different foundation. He suggested that information need emerges as a state of discomfort, psychic tension, dissatisfaction when the barrier occurs on the way of reaching a goal or solving a problem. This state leads to understanding that the dissatisfaction is caused by lack of knowledge how to remove the barrier. Once understood the need may be satisfied in different ways: through getting information from another person, experiment, or otherwise. If an individual decides to turn to recorded information a documentary need emerges. If a suitable document is not at hand, the bibliographic information (or metadata) is required, thus bibliographic need is formed.

Despite being far from resolved, the problem of structuring information needs dissapeared from the literature by 1989.

The types of information needs were and are still usually related to the types of users or types of information resources. Popilova (1967) and Vysotskij (1968) were the first to suggest two ways of grouping information needs: according to how the required information would be used (theoretical, technological, organizational, methodological, scientific); or according to the type of required information (about subjects, about facts, about theories). The other popular division of information needs rests on the chronological criteria: need for retrospective information and need for current information (sometimes need for prospective information is included).

The most popular typologies of information needs followed the classifications of professions in the Soviet Union. Professional information needs are most often researched in Russia and Lithuania. Researchers devoted most attention to the needs of specialists in chemistry, geology, medicine, and agriculture. Information needs of construction specialists, economists, or humanists attracted much less interest, though doctoral studies were also devoted to the needs of musicians (Gradobojeva 1996) and lecturers in the humanities (Kasjanova 2002).

Voverienė (1996) has determined the attributes of professional information needs: dynamic character, dependence on the discipline and type of research, dependence on performed functions, distinction between 'objective need' and the body of inquiries reflecting that need. Voverienė also used the earlier suggested typology by Vysotskij to explain the structure of professional information need, which according to her includes the following elements: need for bibliographic information, need for factual information, and need for conceptual information. All of them can differ according to the width and depth of interests and chronological requirements. These needs form a foundation for investigation of needs of the users for information systems and services.

Another popular classification of information needs takes into account the function performed by a user: governing level, leader, lecturer, student, scientist, etc. The group that was and is most explored is the group of scientists and researchers (Soboleva & Chistiakov 1990; Kugel' et al. 1996).

Sokolov (2002) uses the term 'communication needs' and suggests a different approach to their classification. He distinguishes a need for biological information (needed for normal biological activity), a need for social information (serving spiritual need), and a need for professional information. In spite of the change in terms he deals mainly with information needs. Sokolov still retains the term 'information need' in his complicated typology but it is applied only to a 'group communication need' for professional information.

Finally, for the purposes of professional practice the variety of information needs is divided in several ways:

From the beginning of the 1990s the term information behaviour ('informatsionnoje povedenije') emerges in Russian LIS literature. From the start it is closely related with information literacy: Ivankin (1991) suggested models designed to assist in choosing the best strategy and tactics in information interactions. Other researchers directed their attention to the information behaviour of scientists as representatives of the scientific elite. This concept was defined as actions and efforts that a person makes to get and use new knowledge or transfer and disseminate it in the community (Kugel' et al. 1995: 12). It is not only closely related to the level of information literacy of a person but also to social differentiation on the basis of competent orientation in information space (Brezhneva 2003, Dresher et al. 2005). A questionnaire for scientists in St. Petersburg was designed to provide empirical data on the sources and channels of information, intensiveness of informal professional communication, ways of disseminating new information in the community, and self-evaluation of personal awareness (Kugel' et al. 1995). Thus, the investigation was following a wider concept than usual information need research, though still did not move away from the basic understanding of scholarly communication defined in the 1960s (Mikhailov et al. 1965). Recently, Maksimov and Zabegaeva (2001) have also introduced the term 'information behaviour' in the sense of information search behaviour of the user in interaction with an information retrieval system. They suggest that users fall into four types according to the activity and capability of reflection that influences their action, affective, cognitive, situational and decision states. In turn, these states affect their intentions, actions, perceptions and evaluations. However, the authors try to derive the data about this complex behaviour indirectly: from the logs of queries and statistics of the users of databases in ISIS RAS (The Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences of the Russian Academy of Science).

Research into information needs in Russia and Lithuania closely follows the developments in the library and information science fields and rests on the common conceptual and theoretical foundations and approaches. Mostly, information needs were investigated in relation to the development of systems and services of information provision in the Soviet Union. Therefore, the greatest number of researchers was, and still is, engaged in the investigation of professional information needs of various specialists, or different categories of managers and leaders in industry, science, higher education, etc. There is also a trend to investigate the needs of a 'territorial' (regional) user. Theoretical developments followed the needs of this type of research and also certain ideological restrictions. The underpinning concept of a human being as an information processing system did not change much in information use research. The notion of the hierarchy of needs from individual (on the lowest level) to societal (on the highest hierarchical level) underpinned by the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity is retained up to the present day. Professional information needs occupy the central part in this hierarchy.

The Lithuanian studies on information needs not only followed the patterns of similar research in Russia: two Lithuanian authors - Voverienė and Kancleris - gained authority in the field and led the creation of new concepts and understanding of information needs.

Despite this general trend, determined by the applied direction of information needs research, the development of theoretical concepts did not stagnate, and a variety of schools of thought or directions, such as psychological, based on the concept of activity, or communicational, have emerged and contributed to the overall understanding of the problem.

It is interesting to compare the development of the concept of information needs between two broad and deep traditions, the Eastern and the Western. How do these two traditions relate to each other? The easiest way to explore this would be, of course, to check the citations of the Eastern authors in the works of the Western writers and vice versa. We have put a considerable effort to trace these mutual citations and have found that these two traditions were developing in virtual isolation. Several studies of information needs conducted in East European countries were reported in the Annual Review of Information Science and Technology in the 1970s. Several articles from a leading Russian journal Naucho-tekhnicheskaja informatsiya found their way into these reviews by Allen (1969) and Lipetz (1970). One big Russian study (conducted in 1969-1970) even found its way into the International Social Science Journal (Goldberg 1971). We have failed to detect any other references to the East European research in the literature on information behaviour in the West. Even the most recent comprehensive research guide (Fisher et al. 2005) including the strong but much smaller Scandinavian research tradition fails to list any East European name, except Vygotsky and Volosinov who never did any information behaviour research and figure as the authors of broad theoretical frameworks in the social sciences.

On the other hand, the Western research tradition in information behaviour and needs research was never cited by East Europeans until recently. Two reviews of ISIC conferences (Macevičiūtė 1997; 2000) have introduced this tradition to Lithuanian researchers and one to Slovenian ones (Vilar 2005). There was also a paper by Gaslikova (1999) reviewing the ISIC 1998 papers in the light of the creation of computerised information systems, but it was published in Information Research, not in any Russian journal. Two articles in Information Research show that Estonian (Tibar 2000) and Polish (Niedźwiedzka 2003) researchers are applying Western approaches in their research. The first mention of Western authors writing on information behaviour - Ingwersen, Belkin and some others - has appeared in Russia quite recently(Maksimov & Zabegaeva 2001).

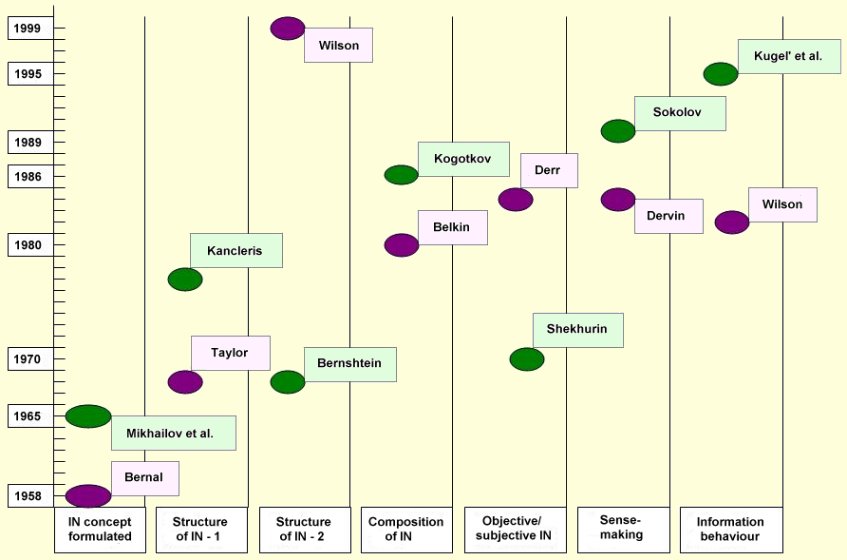

Despite the invisible walls separating those two traditions along the borders of the previous 'socialist camp', one can see either parallel development of some concepts and approaches or emergence of similar ideas during different periods of time.

First, it seems that the factors directing the focus or researchers to information needs were similar during the 1960s and 1970s in both traditions. According to Menzel (1966), 'the end of 1963 seems to have been something of a take off point for empirical research on the information needs and uses of scientists and technologists'. The research of this period in the West is concentrated on information needs of this group in the course of their professional activities and in relation to provision of information services or performance evaluation of information systems. One of the most important contexts for information needs research is scientists' communication. The same trend is common to the information needs research in Russia and surrounding countries. Moreover, Paisley expresses the urgent need for '...theories for information-processing behaviour that will generate propositions concerning channel selection; amount of seeking; effects on productivity of information quality, quantity, currency and diversity...' (Paisley 1968: 3). He proposes a conceptual framework of 'the scientist within systems', such as culture, political system, legal/economic system, membership group, reference group, invisible college, a formal organization, a work team, and a formal information system. To some extent this framework echoes the concept of a human being as information processing tool and the hierarchy of information needs by Shekhurin.

In the 1970s a discussion emerges in Aslib Proceedings on how to separate information needs, wants, demands, use, and requirements (Line 1974; Roberts 1975). In fact, it follows the same pattern as the discussions of 1960s and 1970s in Russia and has the same purpose: to sort out the terminological confusion.

The origin of information needs also was in the focus of Anglo-American researchers. The concept represented here by Kogotkov's model is an interesting case as it can be compared to several models and theories in this tradition. First, a parallel can be drawn between Kogotkov's origin of information need (1986) and Wilson's suggestion (1981) that 'information need' is a secondary order need, which is caused by desire to satisfy primary needs. In pointing out the origin of information need from the understanding of a gap between possessed information and unknown information, the representatives of 'psychological school' use an approach similar to Belkin's 'anomalous states of knowledge' (Belkin 1980). Kogotkov's process of seeking information for satisfaction of the need follows similar steps and involves similar decisions as Taylor's pre-negotiation decisions by the inquirer (Taylor 1968). I would also note that though Kogotkov describes the state of information need in cognitive terms, there is a definite similarity to Dervin's sense-making approach (Dervin 1983; Dervin & Foreman-Wernet 2003). However, Sokolov's concept of communication need as a need for seeking meaning to eliminate the dissonance in one's consciousness is the one closest to Dervin's ideas, at least on the surface.

The structure of information need as generalised by Kancleris is comparable to Taylor's levels of information need, though described in other words:

There is a clear parallel between the two models following the logic of the library reference service. There is also a certain resemblance between the early structure of information need based on the stages of problem solving by Bernshtein (1967) and Wilson's uncertainty resolution within the problem resolution chain (Wilson 1999), though they are used in different ways and for different purposes. The place of stress as an activating mechanism for information seeking in Wilson's model (Wilson & Walsh 1996) is similar to psychic tension and dissatisfaction in Kogotkov's concept (1986) where they play a similar role.

In 1983, Derr analysed information need as an objective phenomenon almost in the same sense as Shekhurin in 1968. He suggested that, '...an information need is a condition in which certain information contributes to the achievement of a genuine or legitimate information purpose' and that, '...[i]t is an objective condition rather than a psychological state'. As a consequence, if the researchers are to determine the information needs of typical users of information systems, they first must identify the latter's information purposes… Intensive psychological study of users is not required to identify information needs. (Derr 1983: 276).

The issue of objective and subjective information of the beginning of 1980s to some extent mirrors the same problem in a reversed order (Dervin & Nilan 1986: 13).

Some criteria for the definition of information needs were described by Lin and Garvey. They propose that needs differ according to the type of work the user is engaged which is almost identical to the classification according to the function that user performs in Russia. They also suggest the 'categorisation according to the substance-versus-channel dimension' (Lin & Garvey 1972: 10-11), which roughly coincides with that based on types of required information by Voverienė (1996) and Vysockij (1968).

Most probably, one can find more and closer parallels between two traditions of information needs research; however, Russian and East European researchers were not much concerned with information seeking outside the working, professional, or research context. Students and youth are the only exception. The rest were treated usually as 'territorial users' to be served by local or regional libraries and information services. One can also see a clear difference from the recent research in the West: the investigation of everyday life information behaviour is non-existent. On the other hand, a huge body of reading studies covers, to some extent, the topic of everyday life information seeking.

There are also no empirical studies in information use or seeking that would result in the development of new, wider theories and change of the old concepts, though applied studies of various user groups (professional, regional, organizational, etc.) are carried out regularly.

The differences and similarities between the Anglo-American and Russian tradition of information needs research can be roughly mapped on a time scale. The time gap between different developments varies from four years to twenty-one years. Four out of six ideas mentioned in this article occurred earlier in Anglo-American literature and two first originated in Russia.

It is quite clear that the same object of investigation and the needs of professional practice as well as similarities in research process lead the researchers to the discussion of similar issues. Though it is most probable that, following their own tradition, they will find different answers and solutions, some of them may have common dimensions and even coincide entirely. This phenomenon is well known to science. However, in each discipline and area of research the similarities and differences are unique. I am sure that I have only scratched the surface in comparing the development of information needs research between two bodies of research.

The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of my students at Vilnius University, Lina Butvilavičiūtė and Lina Markevičiūtė who did the main job retrieving and processing relevant bibliographic materials and documents. The author is also grateful to Professor Tom Wilson for useful advice and support as well as to the participants of ISIC2004 who encouraged me to develop a research note into a paper.

| Find other papers on this subject. |

|||

© the author, 2006. Last updated: 14 March, 2006 |