vol. 13 no. 4, December, 2008

vol. 13 no. 4, December, 2008 | ||||

This paper reports research into the use of mobile information systems by police forces in the UK, which has been carried out over a number of years. The work has been supported by a number of police forces, by the Police IT Organization (now the National Policing Improvement Agency), by system vendors and by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

The management of the forty-three police forces in the UK is rather complicated: day-to-day management is in the hands of chief constables, under the overall control of a government department (the Home Office), but with the local Police Authorities (representing local authorities, magistrates and other local community agencies) responsible for ensuring the efficiency and effectiveness of the forces. The Police IT Organization was established to encourage the adoption of common information technologies across the forces, but was judged not to have achieved its aims, following a rather high profile case concerning the destruction of records of sex offenders and by the failure to establish a national Police intelligence database. In 2007, this organization was replaced by the National Policing Improvement Agency, which has a rather wider remit, being charged with the development and/or delivery of:

As may be seen from the list of areas, information technology continues as a major part of the National Police Improvement Agency's responsibilities: the maintenance and further development of national databases, and the continued development of the Airwave voice communication service are specifically mentioned here, and the Agency's own Website adds to these the delivery of the IMPACT Programme for a Police National Database for sharing intelligence and the delivery of the Information Systems Strategy for the Police Service. This last programme is concerned with ensuring that:

Over the past ten years, more varieties of information technologies have become available to the police and a great deal of effort has been expended in selecting, trialling and adopting these technologies. A brief explanation of the main categories of technologies is necessary to give context to the research described here. The technologies involved can be described under the headings shown in Table 1.

| Technology type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Central intelligence systems | Police National Computer |

| Force command and control systems | A number of suppliers provide systems, e.g., Advent Communications, BAE Systems Ltd., Raytheon Systems Ltd., etc. |

| Force intelligence systems | A number of vendors provide systems, e.g., Northgate, etc. |

| Portable devices for 'nomadic' use | For example, laptop computers used by detective teams and Scenes Of Crime Officers |

| Personal devices for operational use | 'Airwave' radio system, PDAs, mobile phones |

| In-car devices | Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) systems, Mobile Data Terminals (MDT) |

| Call handling systems | Systems allowing for the reception, management and allocation of emergency and non emergency calls. Key interface with command and control systems |

Previous research on the information behaviour of police officers is limited: a search on Web of Knowledge for (information behaviour OR information behavior OR information seeking OR information use OR mobile information) AND police) revealed only five items, only two of which (Allen and Shoard 2005; Baker 2005) were relevant. A search on (information system* OR mobile information) AND police) was more productive, resulting in seventy-six items, of which only twenty were potentially relevant to the purpose of this paper. However, seven of the twenty were older papers from an age before the introduction of mobile systems. Running the same searches on Google Scholar produced more 'hits' but no more relevant items.

Some of the references deal with topics that are not the subject of this paper: for example, investigative techniques (Gottschalk and Holgersson 2006), the relationship of police systems to issues of individual privacy (Schellenberg 1997), the relationship between information systems and court proceedings (Allinson 2001), the use of electronic records (Borglund 2005), general management issues (Ashby et al. 2007; Sillince and Frost 1995) and general accounts of the technology (Lewis 1993; Nunn 2001). Very few papers, however, deal with issues relating to mobile use of the technology.

One of the key issues in police information systems is the integration of data from different sources: this is particularly important for officers who are mobile workers, since switching from one system to another on a small, portable device, possibly involving separate log-on and passwords, is not feasible. Consequently, integrated systems and common interfaces are required. COPLINK is an example of such an interface, an '…easy-to-use interface that integrates different data sources such as incident records, mug shots and gang information, and allows diverse police departments to share data easily' (Chen et al. 2002: 271). However, COPLINK is clearly designed for desk operation, rather than for mobile work, although the principles involved may well have application to mobile systems.

Within the limited number of papers devoted to genuinely mobile systems, Hampton and Langham (2005) explored the use of mobile data terminals in Sussex Police (UK). The terminal provided in-car access to the Sussex Police Operational Information System, through which the crew could be managed, receiving instructions from the Force Command and Control Centre and through which they could receive information on incidents in progress. Access was also provided to the Police National Computer, through which the details of suspect vehicles or individuals could be traced. The vehicles within which the terminals were installed could be single-crewed, i.e., one officer manning the vehicle, or double-crewed. Although information use was not the major part of the investigation, the researchers noted:

Since its introduction, the MDT has become an integral part of the working practices of traffic patrol officers. By providing fast secure access to detailed textual information, the MDT has considerably reduced the volume of radio traffic. As a result, productivity has risen and officers, particularly in the case of double-crewed vehicles, are performing their jobs more effectively. (Hampton and Langham 2005: 116-117)

Similar results were reported by Agrawal et al. (2003) in a study of the introduction of mobile data terminals in a police force in one of the northeastern states of the USA.

A Swedish design study (Nulden 2003) revealed a number of dimensions of police patrol activity that would affect the design and development of mobile systems. In the conceptual framework discussed below, these would be regarded as contradictions or tensions: they were, 'dispatched vs. local autonomy' - i.e., the fact that, in general the police officer is dispatched to the scene of a crime or disturbance, but also has autonomy to act independently if he or she happens upon a disturbance; 'reactive intervention vs. proactive work' - i.e., the tension between responding to incidents (which may involve, for example, conflict in the community) and crime prevention (which demands the collaboration of the same community); and 'control vs. support' - i.e., particularly with GPS devices, the tension between feeling secure in that one's position is known to the control centre and awareness that all of one's movements are visible to Control. We shall see that these design dimensions appear in the case studies we describe below.

Allen and Wilson (2005) have explored the resistance to the introduction of mobile information systems in a police force: their work revealed that one implementation (in a detective team) was enthusiastically adopted, while in another (community patrol officers) the innovation was resisted. Gaining acceptance is not simply a matter of top down implementation of systems.

Allen and Shoard's (2005) work, referred to earlier, related to the impact of mobile technologies on the experience of information overload. Management level officers in the West Yorkshire Police force were issued with Blackberry handheld devices, capable of delivering e-mail messages as well as voice communications, voice mail and PDA functions such as calendar and To Do lists. It was found that officers experienced information overload effects, mainly as a consequence of the always on delivery of e-mail messages.

Work by Norman and Allen (2005) explored the implementation of mobile information systems in detective teams and their use by scenes of crime officers concluding that, if the full benefits of the technology were to be obtained, its introduction must be effectively planned and that organizational change would also be necessary.

As part of a series of studies, a survey of the application of mobile information technologies was carried out for the Police IT Organization in 2006. The situation revealed is briefly outlined in Table 2.

| Technology type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Central intelligence systems | All forces provide access, although the mode and level varies. In 2006, approximately 40% of forces provided some level of mobile direct access to the Police National Computer (PNC) to check vehicle and person records (i.e., not using an information intermediary such as a control room operator). This access was primarily from handheld and in-car terminals, although a minority was using laptops or Airwave radio access through the Police Voice Portal |

| Force command and control systems | Virtually no mobile access to command and control systems in the sense of access to the full functionality of the Incident Command and Control System (ICCS). Approximately 10% of forces provided access to read selected parts of ICCS logs (incident details) and only one provided access to allow officers to update logs. This access was primarily read access on in-car terminals with write access at that stage being restricted to laptops. |

| Force intelligence systems | Some 35% of forces provided access to force intelligence systems at some level. This was almost always an abbreviated or reduced level of access and often did not include access to images of persons - a feature seen as being of high value to front-line operational officers. This was almost exclusively read access with only two forces allowing direct input of intelligence and even this was in the form of an e-mail that then required re-entry into the back-office systems. |

| Portable devices for 'nomadic' use | Primarily laptops provided to management level officers. Almost universal provision but relatively few (25% of forces) allowed access to a relatively full set of force systems. The commonest access was to e-mail, then to ICCS and intelligence with PNC. Connectivity varied widely with most devices being limited to dial-up rather than wireless connections. |

| Personal devices for operational use | Airwave radios, providing full communications access and telephony are almost universal (although in some functions, such as detection, relatively little use is made of them). Some forces (less than 10%) also make data available to the device and approximately 30% make use of SMS data from the device for status updating or Automatic Person Location. Many PCs and Police Community Support Officers in town centres will also have access to a 'Town Centre Radio' which links businesses and key local groups with Police. Almost all forces have such schemes in operation but the scope, scale and use of them varies widely. Virtually every force provided mobile phones and personal e-mail devices at some organizational levels - usually Blackberry devices for senior officers and force-issued mobile phones to a range of staff. Blackberrys were also issued (nearly 3,000 in one force) as personal devices for front-line officers, providing access to intranet, e-mail, PNC and intelligence in the main, in three Forces. Windows-Mobile-based devices, mainly PDAs rather than smartphone, were issued, with a similar feature set, in about 20% of Forces. Connectivity was GPRS in all cases with some additional 3G access. |

| In-car devices | All Forces use in-car ANPR at some level. Some forces have invested quite heavily and have a number of vehicles with frequent database update and links to a range of other force systems. In-car mobile data terminals existed in twelve forces (about 25%) but of these deployments only four could be seen as active deployments. One of these, however, had in the order of 1500 terminals. Typical access is to PNC, Intelligence, Integrated Communications Control System (ICCS) logs and Automatic Vehicle Location data. |

| Static monitoring systems | Most forces have access to closed-circuit television in some parts of the Force area although the management arrangements for this, and the scope of it, vary widely. Fixed ANPR systems are also relatively widespread with approximately half of forces having some level of fixed ANPR access. These systems can be used in a small number of forces (two in 2007) with mobile devices that can log into an upstream camera and wait for the fixed system to pass on ANPR 'hits'. |

The conceptual framework adopted for our work is activity theory, which has been elaborated, in relation to information seeking behaviour and information science in general, by Wilson (2006, 2008). Consequently, we shall describe the framework only briefly, and then in relation specifically to the application of mobile information systems to policing activities.

Activity theory is associated with the names of Vygotsky, Luria and Leont'ev (among others) and was originally developed as a psychological theory in opposition to the prevailing Western schools of behaviourism and psychoanalysis (Vygotsky 1978). Through its association with human intellectual development it was rapidly adopted in educational research and, through that avenue, found its way into the West, where its best known advocate is Engeström (see, for example, Engeström et al. 1998).

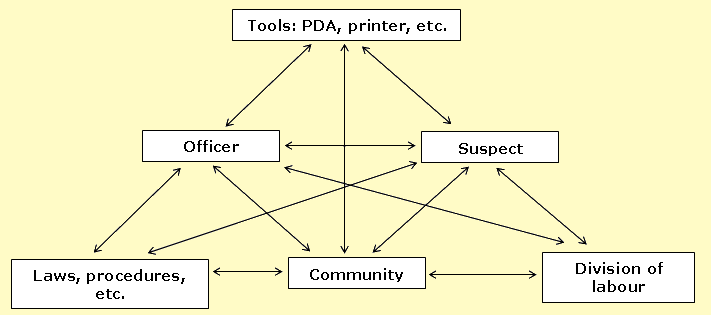

As evolved by Engeström, activity theory models the behaviour of a person or persons (the subject) acting upon an object (other persons, physical objects or states, or social phenomena) to bring about a desired outcome (goal) and using tools and instruments (physical or abstract) to do so. This core activity is carried on through the division of labour, within a community, influenced by (but potentially changing) prevailing rules and norms.

Policing may be seen as an activity of this kind in itself, but may also be seen as embracing a set of distinct activities, such as detection, crime prevention, traffic policing, community policing, major incident management, etc. The three case studies that follow are examples of such activities.

The stopping of suspect persons and vehicles is a common police activity, especially in the major cities of the UK, where illicit drug trading and gun crime are significant social problems. Following complaints from the black community, who felt that they were being unfairly targeted in such operations, police forces have been required to issue a record of the event to the stopped person. A stop does not necessarily lead to a search: if the officer receives a valid account of the person's identity and their reasons for being where they are and behaving as they have been doing, the record is issued and no further action is taken. However a search may result in an arrest, if the person is found to be in possession of stolen goods, or an illegal weapon or other materials that give rise to reasonable suspicion that the person may be involved in criminal acts.

In 2005 a major urban police force implemented a test of a ruggedized Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) and portable printer in its stop and search procedures: some ninety officers were involved in the trial, fifty of them being based in the same division. The device provided a variety of functions: implementation of the stops application, which provided for the recording and printing of the data collected from the suspect; e-mail, connection to the Police National Computer and personal information management functions such as a diary.

Within the activity theory framework, a typical stop activity can be illustrated as in Figure 1. Although only physical tools have been indicated in the diagram, it should be borne in mind that the term also includes intellectual tools. In deciding to make the stop, the officer has already assessed the individual or vehicle and/or the situation and, on the basis of experience and understanding the law, decided that sufficient grounds for a stop exist. In other words, visual information from the scene is acquired and processed by the officer. This may involve his prior knowledge of a person, either gained through experience or through the Force's intelligence system.

The terms community and division of labour also deserve further explanation. Community is somewhat problematical, since several layers and types of community may be involved. For example, both officer and suspect may belong to the same general community of the neighbourhood, town or city; but the officer is also part of the specialized community of the police force and the suspect may be a member of a criminal community.

The division of labour in the situation may be invoked if, for example, the officer is part of a two-person crew of a patrol vehicle: one officer may use various other tools, such as the radio, to obtain information while the other questions the suspect. Further division of labour is involved in that situation if one or other of the officers seeks information from the Command and Control Centre of the force, or if the Police National Computer is queried: that system has been established by others and data have been input by others.

Thus, the activity system reveals complex information types and information flows that are involved in the stop. Some of this information is available as the officer's personal knowledge of the law and of the procedures to be followed in a stop; some is garnered from the suspect.

Road policing is organized quite differently across different forces but the key functions of the role remain common. Road policing units aim to ensure that the vehicles using the roads are safe and legal, that they are used in accordance with the laws and rules of the road, that serious road accidents and incidents are managed and investigated promptly and effectively, and that criminals are denied the use of the roads. This is not an exhaustive list but it covers the key aspects of the work.

The single largest technical development which has affected road policing in the last decade has been the development of Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) systems which are capable of reading number plates and then checking a range of databases to identify vehicles that are either not compliant with relevant rules (usually MOT (the national roadworthiness test), road tax, insurance) or that are associated with people or addresses of interest (such as drink drivers, banned drivers, drug offences). This system can work from fixed camera points or can be vehicle-based. There is a range of different systems available but all work in essentially the same way. When ANPR is not available, checks into the key databases can be undertaken either over the radio system or through mobile, in-vehicle data terminals or handheld computers if they are available; these need to be initiated by the officer as a result of interest in a vehicle.

The typical action that comes out of ANPR use, as well as the more intuitive checks that are done on vehicles when ANPR is not available, is a traffic stop. This consists of identifying a vehicle of interest, stopping the vehicle, making the appropriate checks based on the reason for the stop, deciding on the appropriate course of action, and then processing that action.

In activity theory terms the traffic stop can be represented in a similar manner to the person stop discussed above.

| Activity area | Road policing example |

|---|---|

| Subject | Police crew or officer |

| Object | Composite 'vehicle-with-driver' which is then decomposed. Either or both can be dealt with on a range of bases. Usually, however, vehicle issues automatically re-include the driver - so, for example, a vehicle without a valid MOT test certificate will lead to action against the driver for 'driving a vehicle without an MOT'. |

| Tools | Intuition; knowledge of vehicle specific rules and laws; radio; mobile data terminal; handheld device; database information on vehicle and/or driver legality; forms |

| Rules and norms | Warning vs. action; use of HORT1 form (requiring the driver to produce relevant documents); laws regarding vehicle use; local priorities and targets |

| Community | Road policing unit; drivers and road users |

| Division of labour | Single vs. double crewed; ANPR increases communications load; ANPR and mobile data systems reduce communications load; direct-to-fixed camera access reduces communications load;relationships with vehicle removal companies. |

| Outcome | Vehicle outcomes range from no action to seizure of a vehicle with a view to destruction or disposal. Driver outcomes range from no action to immediate arrest. Numerically, once a vehicle has been stopped on the basis of information that there is cause to do so, the most common outcome is the issue of a conditional-offer Fixed Penalty Notice (usually offering the offender the possibility of attending a remedial driving workshop instead of paying a fine). |

| Tensions | Warnings vs. action. Being seen to be 'reasonable' as against enforcing the law in marginal cases. ANPR hits which are likely to prove unfruitful ('No recorded keeper' is usually due to DVLA not having updated records on vehicle transfer) vs. following up all hits. Balancing time spent in serious RTA work (reactive) vs. proactive patrol work. |

Community policing goes by a number of names, the most current of which is neighbourhood policing, which covers a formal approach to the policing of neighbourhood areas. In a relatively short time it has generated a considerable literature in operational and academic publications. The aim of this approach is to re-connect with local communities, provide a visible police presence in areas, and increase reassurance in communities. This is to be accomplished by the Police in partnership with other agencies and groups rather than in isolation. One of the most visible manifestations of the approach is usually taken to be the use of Police Community Support Officers, although they actually predate the formal introduction of neighbourhood policing by about eighteen months. Neighbourhood policing has been a priority in most Forces for the last four years or so and is usually undertaken in Neighbourhood Policing Teams which consist of management (usually dedicated sergeants and inspectors at an operational level, further control will then form a part of the portfolio of a more senior officer who also covers other areas of policing), Community beat managers (police constables) and Police Community Support Officers. Resources allocated vary but in one northern force, in a typical Basic Command Unit covering town and rural areas the allocation of front-line officers to neighbourhood team work stands at 25% and although this is higher than some others, it is not massively so.

Nighbourhood team work is sometimes presented as being a single set of activities but it is clear from work with Forces that there are actually significant differences between the work of teams in different areas. Officers tend to break the work down into three categories; town centre, estate, and rural, with some adding a distinction between 'estate' and 'housing'.

Town centre work deals with shops and areas such as transport interchanges. The work has relatively few permanent residents and officers working with such areas identify shopkeepers and staff, homeless, and council staff as being the key communities they work with. Problems tend to be shoplifting and similar opportunistic crime, youth anti-social behaviour and evening alcohol related nuisance. The work is highly time and day variable.

According to an interviewed chief inspector, 'estate' tends to refer to 'housing estate with a significant level of deprivation, normally including one or more schools'. Housing would be used for more dispersed areas of usually predominantly middle class housing. The work differs between the two types of area but is in both cases concerned with visible patrol, nuisance and criminal damage. Youth referrals tend to form a significant part of this work, as does liaison with local housing associations and council officers as well as community groups such as Neighbourhood Watch, StreetPride and local wardens.

Rural areas bring a particular character with large areas and dispersed populations. The work in these areas will address nuisance and criminal damage but may also have to deal with burglary, theft from farms and rural businesses and road traffic nuisance. Communities in such areas are often dispersed and represented by interest areas such as farmers, business owners, and rural householders.

While the areas are diverse there are common factors in the work:

In activity theory terms, neighbourhood policing teamwork can be represented in a similar manner to the vehicle and person stops discussed above and is shown in Table 4.

| Activity area | Community policing example |

|---|---|

| Subject | Neighbourhood Policing Team officer; Joint Action partners |

| Object | People as individuals; target areas such as criminal damage |

| Tools | Intuition; local knowledge; radio (and Town Centre Radio); mobile phone; mobile data terminal or handheld device;key individuals and networks knowledge; awareness of targets; forms. |

| Rules and norms | Warning vs. action; use of youth referral forms and stop forms; Police Community Support Officers relationships and areas of work vs. those of police constables; local priorities and targets. |

| Community | Key individuals and networks; Neighbourhood Policing Team; geographic area; community groups |

| Division of labour | Police Community Support Officers vis-à-vis police constable; use of communications highly variable; Community, councils and housing associations joint actions; PACT (Partnerships And Communities Together) activities. |

| Outcome | Increase in reassurance; reduction in measured incidents; building relationships with communities and people within them, including key individuals and networks. |

| Tensions | Warnings vs. action; being seen to be 'reasonable' as against enforcing the law in marginal cases; balancing time spent in reactive work vs. proactive patrol work; dealing with KIN as against wider visibility; Police Community Support Officers powers vs. relationships |

Our studies have been concerned with the reception of information technology innovations in police forces, rather than on the information behaviour of officers per se. However, in each of the cases dealt with above, we can identify how the introduction of mobile devices changes (or fails to change) the existing information behaviour of officers.

First, in the case of stop and search, a paper-based activity becomes a (small) screen-based activity and, because of the capacity to interact directly with Force and national databases, voice communication over the radio link is minimized. The temporal duration of the interaction is also affected by the new technology: instead of waiting to communicate by radio to someone in the command and control centre and then going through several iterations of enquiry as the interview with the suspect proceeds, the officer is able to complete the process much more rapidly and is able to issue a record of the interaction, rather than requiring the person stopped to visit a police station to collect the same information. In both the pre- and post-innovation situation, however, the personal knowledge of the officer, gathered through experience on the street, plays a major role in determining whom to stop.

Information behaviour in relation to the traffic stop is affected in very similar ways, in that the technology (both in-car terminals and portable data terminals) allow interaction with force and national databases, which provide information previously only available through communication with the force command and control centre. Also, providing that the information given by the offender is accurate and true, the incident can be completed more rapidly and, unlike in pre-technology days, fewer drivers will be required to attend police stations with their driving documents and insurance certificates to complete the incident.

In the case of neighbourhood policing, the key area of development from the point of view of information availability, is the collection, collation and computer handling of intelligence from the community. Whereas earlier an officer would rely upon personal knowledge and that gained from colleagues working the same patch, the introduction of mobile technology has given access to the force's intelligence database, which can be consulted directly, at any time. Consequently, when dealing, say, with a problem family on a housing estate, the officer can now obtain a great deal of information from the force's intelligence system, discovering, for example, that someone in the family is dealing drugs, or is suspected of being armed. Information of this kind is likely to lead to the officer having back-up in making the approach to the family, rather than, potentially, going into a problematical situation unaware of the fact that it could be problematical.

The flow of information in the cases described is always very tightly associated with the nature of the task, to the extent that the officers themselves are not able to separate task from information. The information drives the task and the circumstances of the task drive the need for information.

Our analysis of the limited range of policing activities described in the case studies reveals that activity theory is a very useful conceptual framework, drawing attention to contextual issues and to the consequences of the tensions and contradictions that exist in the implementation of information technologies in an emergency response service.

We have observed that, all too often, Forces are attempting to introduce a technology as a tool, rather than considering the effect of that tool on the work process undertaken by those who use it. As a result, complex issues of organizational change and even the need for individuals to change their work habits are ignored. Consequently, pilot projects may be deemed to have 'failed' when, in fact, they have not been properly introduced. This aspect of the problem of introducing new technologies is related to the different 'cultures' that operate within any organization. These cultures have different motives, different expectations of outcomes and different ways of judging the success of an initiative. Thus, the senior management of a Force may introduce the technology with the aim of keeping the officers on the street, rather than needing to return to the police station to search for or record information. The information services division may want a technology success to demonstrate their competency in this area, while the operational officer may see the device as something that makes him or her more autonomous in action. These differences, unless they are effectively dealt with, are a constant source of tension within the Force.

The analyses show that the complexity of the information tasks undertaken will vary considerably with the complexity of the activity. A simple stop and account activity, which results in the identification of a non-criminal person has very straightforward information flows, while one that involves a confirmed suspect will demand more in the way of interrogation of the Police National Computer database and local Force intelligence databases.

Similarly, in the case of a traffic stop, if a vehicle is stopped because the ANPR database records non-possession of insurance and the driver produces an insurance certificate, he or she will be on the road again very quickly and the information transfer involved is simply visual verification of the certificate, together with a certain amount of oral communication between officer and driver. However, if the database reveals that the vehicle is believed to be stolen and the driver falsely attempts to hide the fact that he or she is not the registered owner, considerably more information activity will be involved, possibly resulting in the arrest of the individual and the immobilizing of the vehicle until it can be transferred to the Force's vehicle pound.

Neighbourhood policing is similarly varied in its character with officers balancing reconnecting with local communities (nice cop) with the effective action required to deal with the issues those communities raise (nasty cop). This raises complex issues of information management, in that the priorities for an area have to be identified effectively, the local knowledge and the intelligence resource of the police constable and the police community support officers have to be used to identify action that will achieve the desired result without damaging relations (too much) or abstracting resource from other areas with a consequent rise in crime in those areas. In addition, the feedback mechanisms for success are a mix of formal indicators, such as reported incidents, and informal indicators, such as conversations with local people. At the moment many Forces are grappling with the complexities of information management in NPT and specifically, reducing the administrative burden required to collect, manage and use the information needed.

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for their thoughtful comments on the original paper. While we have not always been able to implement the changes they suggest, we do believe that they will be useful for our future work.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the authors, 2008. Last updated: 19 November, 2008 |