vol. 14 no. 4, December, 2009

vol. 14 no. 4, December, 2009 | ||||

The main purpose of business intelligence systems is 'to provide knowledge workers at various levels in organisations with timely, relevant and easy-to-use information' and 'to provide the ability to analyse business information in order to support and improve management decision making across a broad range of business activities' (Elbashir et al. 2008: 135, 136). Such systems primarily support analytical decision-making and are used in knowledge-intensive activities. These activities have three significant characteristics: they are often non-routine and creative (unclear problem space with many decision options) (Eppler 2006), their specifications cannot be predefined in detail, their outcome is uncertain and yet their success often brings innovations and improvements.

In general there is great interest among researchers and professionals in measuring the bottom-line contribution of information technology. Since the impact of business intelligence systems on organizational performance is primarily long-term and indirect, most measures of the value of information technology to business are not able to measure the immediate influence of such systems. However, we can use different measures of the benefits (Watson et al. 2002, DeLone and McLean 2003, Petter et al. 2008). Benefits such as time savings and better information are, according to Watson et al. (2002), the most tangible and have a high local impact, whereas the benefits of business process improvement have a high potential global (organization-wide) impact but are much harder to measure. Consequently, measures of improved information quality as a result of implementing business intelligence systems are commonly used (Watson et al. 2002).

The existing literature suggests that the quality of information is a vaguely defined concept (Lillrank 2003, Eppler 2006) and there is no single established definition for it (Ruzevicius and Gedminaite 2007). The term information quality encompasses traditional indicators of data quality (Pipino et al. 2002, Strong et al. 1997), factors affecting the use of information (Low and Mohr 2001) such as comprehensiveness and suitability of information and features related to information access (Spahn et al. 2008) such as speed and ease of access. To understand and analyse the benefits of business intelligence systems that chiefly support knowledge-intensive activities it is necessary to understand information quality as a broader concept, which embraces all of the above-mentioned aspects. We assert that information quality focuses on two main aspects, namely the content of information and its accessibility.

The implementation of business intelligence systems can contribute to improved information quality in several ways, including faster access to information, easier querying and analysis, a higher level of interactivity, improved data consistency due to data integration processes and other related data management activities (e.g., data cleansing, unification of definitions of the key business terms and master data management). However, to understand how much the implementation of business intelligence systems actually contributes to solving issues of information quality in knowledge-intensive activities it is important to be familiar with the problems that may arise. Lesca and Lesca (1995) emphasise the information quality problems that knowledge workers often face: limited usefulness of information due to an overload of information, ambiguity due to lack of precision or accuracy leading to differing or wrong interpretations, incompleteness, inconsistency, information that is not reliable or trustworthy, inadequate presentation and inaccessible information. Similarly, Strong et al. (1997) also note problems such as too much information, subjective production and changing task needs. Another analysis of knowledge work problems related to information quality is found in Davenport et al. (1996): knowledge workers are faced with variety and uncertainty of information inputs and outputs, they often struggle with poor information technology support, and they face unstructured problems. Hence, all these researchers agree that the major problems of providing quality information for knowledge-intensive activities relate to information content.

The implementation of business intelligence systems, involving both technology and organizational changes, should therefore contribute primarily to improving the quality of information content since this can impact on the accomplishment of strategic business objectives through improved decision-making (Slone 2006, Al-Hakim 2007, Eppler 2006). Our research tries to answer the question of whether the implementation of business intelligence systems adequately addresses all the information quality problems that knowledge workers most often encounter. More precisely, does the implementation of business intelligence technologies and related data management activities contribute in particular to improved media quality (i.e., quality of access to information) or does it also focus adequately on the content aspects of information quality, where the major problems of providing quality information lie. Therefore, in this study we aim to present and test a model of the relationship between business intelligence systems and information quality and to evaluate the potential differential impact of business intelligence system maturity on the content and media components of information quality.

The outline of the paper is as follows: Section 2 sets the theoretical grounds for business intelligence systems' maturity and information quality for our research. Section 3 conceptualises the research model leading to the development of suitable hypotheses. Section 4 presents a methodological framework for the study, while Section 5 provides the results of the data analysis. Section 6 concludes with a summary and a discussion of the main findings.

According to Thierauf (2001), today's business intelligence systems play an important role in the creation of current information for operational and strategic business decision-making. Elbashir et al. (2008: 138) define business intelligence systems as 'specialized tools for data analysis, query and reporting, that support organizational decision-making that potentially enhances the performance of a range of business processes'. Negash (2004: 177) refers to business intelligence systems as systems that 'combine data gathering, data storage and knowledge management with analytical tools to present complex internal and competitive information to planners and decision makers'. The above definitions share the same is the idea that 'these systems provide actionable information delivered at the right time, at the right location, and in the right form to assist decision-makers' (Negash and Gray 2008: 176). The purpose is to facilitate information users' work by improving the quality of inputs to the decision process. (Macevičiūtė and Wilson 2002, Negash and Gray 2008).

In this research we have adopted the definition of the business intelligence environment provided by English for the systems we are discussing:

Quality information in well-designed data stores, coupled with business-friendly software tools that provide knowledge workers with timely access, effective analysis and intuitive presentation of the right information, enabling them to take the right actions or make the right decisions'. [emphasis in the original]. (English 2005)

Compared to earlier decision support systems, business intelligence systems are derived from the concept of executive information systems and provide artificial intelligence capabilities as well as powerful analytical capabilities, including features such as online analytical processing, data mining, predictive analytics, scorecards and dashboards, alerts and notifications, querying and reporting and data visualisations. (Turban et al. 2008). Looking at the historical evolution of decision support, Frolick and Ariyachandra (2006) establish that older decision support systems and executive information systems were application-oriented whereas business intelligence systems are data-oriented; centred upon data warehousing, they provide the analytical tools required to integrate and analyse organizational data. In contrast to transactional systems, which focus on the fast and efficient processing of transactions, business intelligence systems focus on providing quick access to information for analysis and reporting. While business intelligence systems support decision-making, adapt to the business and anticipate events, transactional systems concentrate on automating processes, structuring the business and reacting to events.

In the view of Davenport and Harris (2007), organizations must tackle two important issues in constructing their business intelligence system's architecture: the integration of available data and analytics. This is in accordance with English's (2005) definition (above) which emphasises well-designed data stores (integration) and appropriate tools that provide access to information along with the analysis and presentation of information (analytics). Data for business intelligence originates from many places, but must be managed through an enterprise-wide infrastructure. It is only in this way that business intelligence will be streamlined, consistent and scalable. Choosing the right analytical tools is also important and depends on several factors. The first task is to determine how thoroughly decision-making should be embedded into business processes (Gibson et al. 2004). Next, organizations must decide whether to use a third-party application or create a customised solution. Last, information workers naturally tend to prefer familiar products, such as spreadsheets, even if they are not well suited to the analysis at hand (Davenport & Harris 2007).

When considering a business intelligence system as an information technology investment, Chamoni and Gluchowski (2004) and Williams (2004) suggest that it is important for organizations to strive after a mature business intelligence system in order to capture the true benefits of business intelligence initiatives. Early maturity model approaches in the field of information systems emerged from the area of software engineering and aimed at measuring and controlling processes more closely (Humphrey 1989). Based on different characterisations of information technology and/or information system maturity, various maturity models were put forward. For example:

As can be seen from the above examples there are many information technology and/or information system maturity models dealing with different aspects of maturity: technological, organizational and process maturity. For the purpose of this paper we are interested in how the implementation of business intelligence systems, which includes business intelligence technologies and data integration processes, provides information quality. We could not rely directly on previous maturity models because they are quite general and their focus is not on the key technological elements of business intelligence systems as previously broadly defined. In the current business environment, there is no scarcity of business intelligence maturity models (Chamoni and Gluchowski 2004, TDWI 2005, Williams & Williams 2007), yet after a thorough literature review we found no business intelligence or business intelligence systems maturity models that were empirically supported.

The information goal of business intelligence systems is to reduce the gap between the amount and quality of data that organizations collect and the amount and quality of information available to users on the tactical and strategic level of business decisions. In business practice this information gap comes in different forms: data sources are inconsistent, organizations possess data they are unaware of, data owners are too protective of information, data within operational databases is not properly arranged to support management decisions, analysts take too much time to gather the required information instead of analysing it, management receives extensive reports that are rarely used or inappropriate, information systems staff play the role of data stewards because of an increased need for information in analytical decision processes, there is a lack of external and/or competitive information to support decision-making and there are limitations of incompatible software/hardware systems.

From the above examples we can derive two important considerations. First, the information gap indicate low levels of business intelligence system maturity in terms of data integration and analytics. Second, we can see examples of poor information quality. When thinking about the maturity stage of a business intelligence system, the quality of information is an important issue on the path to achieving business value (English 2005).

Researchers on information quality have pondered the question of what can qualify as good information. Huang et al. (1999: 34) suggest that the notion of information quality depends on the actual use of information and define information quality as 'information that is fit for use by information consumers', Kahn et al. (2002) see information quality as the characteristic of information to meet or exceed customer expectations, while Lesca and Lesca (in Eppler 2006: 51) define information quality as the 'characteristic of information to be of high value to its users'. In this study we understand information quality as meeting customers' needs for information while minimising or eliminating defects, deficiencies and/or nonconformance in the information product or process.

Early important studies on information quality date from the 1970s and 1980s: Grotz-Martin (1976) conducted a study on the quality of information and its effects on decision processes, while Deming (1986) established fourteen quality points for management to transform business effectiveness. Other more recent studies (Crump 2002, English 1999, Ferguson and Lim 2001, Lillrank 2003) address the issue of information quality in the context of numerous disciplines ranging from pedagogy and legal studies to rhetoric, medicine and accounting.

Regardless of the differences in their research contexts, goals and methods, researchers have built a surprising consensus about the criteria that can be used to describe the value of information (Eppler 2006). Conceptual frameworks and simple lists of information quality criteria that describe the characteristics which make information useful for its users abound in the management, communication and information technology literature (Davenport 1997, Kahn et al. 2002, Lesca and Lesca 1995, van der Pijl 1994). Some of these frameworks are also suitable for evaluating the quality of information provided by business intelligence systems. The perspective of an information producer on the quality of information may differ from that of an information consumer, so it is ultimately the information consumers who assess whether the information is fit for their uses. Therefore, the quality of the information cannot be assessed independent of those using the information (Strong et al. 1997).

In the view of O'Reilly (1982), information quality and accessibility are believed to be very important characteristics that determine the degree to which information is used. According to Khalil and Elkordy (2005: 69), 'the relatively limited previous empirical research on information quality and information systems' effectiveness suggests a positive relationship between perceived information quality and information use'. Several authors also claim that the provision of quality information is the key to gaining a competitive advantage (Owens et al. 1995, Ruzevicius & Gedminaite 2007, Salaun and Flores 2001). Also, managers were found to be likely to trust high quality information and hence to be more likely to rely on such information in making decisions or evaluating performance (Low and Mohr 2001). In their researches, Seddon and Kiew (1994) and McGill et al. (2003) also found user-perceived information quality had a large positive impact on user satisfaction with organizational systems and user-developed applications.

Not many attempts have been made to define scientifically the maturity of business intelligence systems, although many models can be found in the professional field. Business intelligence system maturity models describe the evolution of an organization's business intelligence system capabilities. TDWI (2005) proposes analysing the technological part of business intelligence maturity through a system's architecture, scope, type and analytics. Chamoni and Gluchowski (2004) emphasise technology as one of the three categories in their five-stage business intelligence system maturity model, with analytics and system design as the top priorities.

For developing a long-term, efficient and scalable business intelligence architecture, Moss and Atre (2003) point out the importance of data integration, choosing the right data sources and providing analytics to suit the users' information needs. In the same context, Gangadharan and Swami (2004) propose an effective data integration process, integrated enterprise portal infrastructure and the delivery of answers to all key business questions as criteria for evaluating the completeness and adequacy of business intelligence systems' infrastructure.

We found no evidence of an agreement on the business intelligence systems' maturity concept in the business intelligence and business intelligence system maturity models reviewed. In line with the purpose of our research we can derive two main emphasises from the reviewed models. First, there is an awareness of the importance of integrating large amounts of data from disparate sources (Jhingran et al. 2002, Elbashir et al. 2008, Lenzerini 2002) and of the need to cleanse the data extracted from the sources (Rahm and Do 2000, Bouzeghoub and Lenzerini 2001) within the field of business intelligence systems. Secondly, organizations are focusing on technologies (e.g., querying, online analytical processing, reporting, data mining) for the analysis of business data integrated from heterogeneous source systems (Davenport and Harris 2007, Negash 2004, Thierauf 2001, Turban et al. 2008). On this basis, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1: Business intelligence system maturity is determined by data integration and analytics.

The field of information quality evaluation has already been extensively researched (Raghunathan 1999, Salaun and Flores 2001, Lee et al. 2002, Eppler et al. 2004, Slone 2006, Forslund 2007, Wang et al. 1995, Eppler 2006). For evaluating information quality we adopted Eppler's (2006) information quality framework. Eppler provides one of the broadest and most thorough analyses by reviewing relevant literature on information quality where seventy criteria for quality were identified, some of them partially or fully overlapping. The framework of sixteen criteria provides four levels of information quality: relevant information, sound information, optimised process and reliable infrastructure. The logic for having these four levels is based on the knowledge media theory of Schmid (Schmid and Stanoevska-Slabeva 1998). The upper two levels, relevance and soundness, relate to actual information itself and are labelled content quality. The lower two levels, process and infrastructure, relate to whether delivery process and infrastructure are adequate in quality and are labelled media quality to emphasise the channel by which information is transported (Eppler 2006). Content quality includes characteristics such as comprehensiveness, correctness, consistency, clarity, relevance and applicability, while media quality includes characteristics such as timeliness, convenience and interactivity. For end-users, both aspects, media and content quality, may be perceived as one final product: information and its various characteristics.

The foremost purpose of implementing business intelligence systems is to increase the level of information quality provided to knowledge workers at various levels of an organization. From the literature review (for example Lesca and Lesca 1995, Strong et al. 1997, Davenport et al. 1996) we conclude that the key problem when providing quality information for knowledge-intensive activities relates to information content. Similarly, Eppler (2006) concluded after scanning the vast available academic literature and empirical surveys on knowledge workers that the main information quality problem areas (the amount of information and its structure and format) are closely related to content quality.

Koronios and Lin (2007) identified some business intelligence technologies and activities, namely data cleansing, data integration, data tools and data storage architecture, as key factors influencing information quality. For example, data warehousing can imply an increase in content quality from the comprehensiveness and consistency criteria through data integration and cleansing, but it can also improve media quality since users do not have to search for data within different data sources and combine it to create information. In terms of data integration, the implementation of business intelligence systems therefore contributes to both information content quality and information media quality. Data management activities should result above all in content quality.

Moreover, business intelligence system maturity can influence content quality through a feedback loop: a better insight into data allows the perception of errors at data collection which consequently improves data quality control at data collection. In terms of analytics, the higher maturity of analytical technologies (e.g., interactive reports, online analytical processing, data mining and dashboards) is expected to have an impact on both media quality and somewhat on content quality. For example, through improved interactivity (a media quality characteristic) users do not receive information passively but are able to explore it and gain more relevant information (a characteristic of content quality) for appropriate decisions. Nevertheless, Eppler (2006) argues that technology mainly influences media quality and has limited possibilities of influencing content quality. We can thus presume business intelligence systems' maturity affects both dimensions of information quality in different ways.

In this paper we propose the concept of information quality as involving two dimensions that are both positively, yet differently affected by the maturity of business intelligence systems. In this context, hypotheses 2a, 2b and 3 are put forward:

H2a: Business intelligence system maturity has a positive impact on content quality.

H2b: Business intelligence system maturity has a positive impact on media quality.

H3: Business intelligence system maturity has different positive impacts on content quality and on media quality.

We started developing our questionnaire by building on the previous theoretical basis to ensure content validity. Pre-testing was conducted using a focus group of three academics interested in the field and seven semi-structured interviews with selected Chief Information Officers who were not interviewed later. This was also done to ensure face validity. An important outcome of the pre-testing was the exclusion of some data sources from the questionnaire since they were sufficiently represented through the data integration. Besides pre-testing, a pilot study was conducted on a small sample of Slovenian companies with more than 250 employees. On that basis, the set of measurement items was expanded. We used a structured questionnaire with sevent-point Likert scales for the information quality items and a combination of seven-point Likert scales and seven-point semantic differentials for those items measuring business intelligence system maturity. According to Coelho and Esteves (2007), a scale with more than five points generally shows higher convergent and discriminant validity than a five-point scale and greater explanatory power thus confirming higher nomological validity. The participants were given letters that explained the aims and procedures of the study and assured them that the information collected would not be revealed in an individual form.

Measurement items were developed based on the literature review and expert opinions. All constructs in the proposed model are based on reflective multi-item scales.

Based on the reviewed business intelligence and business intelligence systems' maturity models we modelled the business intelligence system maturity concept as a second-order construct formed by two first-order factors: data integration and analytics. Through the data integration construct we seek to measure the level of data integration for analytical decisions within organizations through two indicators: i) how the available data are integrated; and ii) whether data in data sources are mutually consistent. Here it is appropriate to note that data might be scattered over a multitude of data sources and yet be logically integrated (Bell and Grimson 1992), which we took into account when setting up the data integration indicators (see Table 1).

Our data integration construct is also supported by the findings of Lenzerini (2002) who argues that for organizations: a) the problem of designing data integration systems is important in current real world applications; b) data integration aims at combining data residing in different sources and providing the user with a unified view of these data; and c) since sources are generally autonomous in many real-world applications the problem arises of mutually inconsistent data sources. Within the analytics construct we look at the different analyses the business intelligence system enables. Although many kinds of analytics are provided by the business intelligence system literature, we selected those indicators most used in previous works: paper reports (TDWI 2005, Williams and Williams 2003), online analytical processing (Davenport and Harris 2007, TDWI 2005), data mining (TDWI 2005) to dashboards, key performance indicators and alerts (Davenport and Harris 2007, Williams and Williams 2007).

To measure the quality of information we adopted previously researched and validated indicators provided by Eppler (2006). We included eleven of the sixteen information quality criteria from Eppler's framework in our research instrument. Since we are interested in the quality of available information for decision-making itself we left out those media quality criteria measuring the infrastructure through which the information is actually provided, since they relate to technological characteristics of business intelligence systems that we examine through the business intelligence system maturity construct. According to this framework, the infrastructure level contains criteria that relate to the infrastructure on which the content management process runs and through which information is provided. These criteria refer to a system's easy and continuous accessibility, its security, its ability to be maintained over time and at a reasonable cost and its speed or performance.

Table 1 shows a detailed list of the indicators used in the measurement model.

| Construct | Label | Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Data integration | Circle the number (1 to 7) in the sense of proximity of one of the two available bipolar statements (A and B) | |

| DI1 | Data are scattered everywhere – on the mainframe, in databases, in spreadsheets, in flat files, in Enterprise Resource Planning applications. – Statement A Data are completely integrated, enabling real-time reporting and analysis. – Statement B | |

| DI2 | Data in the sources are mutually inconsistent. – Statement A Data in the sources are mutually consistent. – Statement B | |

| Analytics | (1 = Not existent … 7 = Very much present) | |

| A1 | Paper reports | |

| A2 | Interactive reports (ad-hoc) | |

| A3 | Online analytical processing | |

| A4 | Analytical applications, including trend analysis, 'What-if' scenarios | |

| A5 | Data mining | |

| A6 | Dashboards, including metrics, key performance indicators, alerts | |

| Content quality | (1 = Strongly disagree … 7 = Strongly agree) | |

| CQ1 | The scope of information is adequate (neither too much nor too little). | |

| CQ2 | The information is not precise enough and not close enough to reality. | |

| CQ3 | The information is easily understandable by the target group. | |

| CQ4 | The information is to the point, without unnecessary elements. | |

| CQ5 | The information is contradictory. | |

| CQ6 | The information is free of distortion, bias or error. | |

| CQ7 | The information is up-to-date and not obsolete. | |

| Media Quality | (1 = Strongly Disagree … 7 = Strongly Agree) | |

| MQ1 | The information provision corresponds to the user's needs and habits. | |

| MQ2 | The information is processed and delivered rapidly without delay. | |

| MQ3 | The background of the information is not visible (author, date etc.). | |

| MQ4 | Information consumers cannot interactively access the information. | |

In spring 2008, empirical data were collected through a survey of 1,329 Slovenian medium- and large-sized organizations listed in a database published by the Agency of the Republic of Slovenia for Public Legal Records and Related Services. Questionnaires were addressed to Chief Information Officers and senior managers estimated as having adequate knowledge of business intelligence systems and the quality of available information for decision-making. A total of 149 managers responded while, at the same time, twenty-seven questionnaires were returned to the researchers with 'return to sender' messages, indicating that the addresses were no longer valid or the companies had ceased to exist. Subsequently, follow-up surveys were sent out and resulted in an additional thirty-two responses. The final response rate was thus 13.6%.

The structure of respondents by industry type is presented in Table 2. Given that non-profit organizations were excluded from the study, the sample is an adequate representation of the population of Slovenian medium- and large-sized organizations.

| Industry | Respondents' share (%) | Whole population share (%) |

|---|---|---|

| A Agriculture, hunting and forestry | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| B Fishing | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| C Mining and quarrying | 0.0 | 0.5 |

| D Manufacturing | 46.2 | 50.7 |

| E Electricity, gas and water supply | 5.5 | 3.8 |

| F Construction | 12.2 | 11.0 |

| G Wholesale and retail trade | 12.3 | 14.0 |

| H Hotels and restaurants | 4.4 | 4.1 |

| I Transport, storage and communication | 9.1 | 5.7 |

| J Financial intermediation | 4.9 | 5.1 |

| K Real estate, renting and business activities | 2.4 | 3.1 |

| Not given | 1.9 |

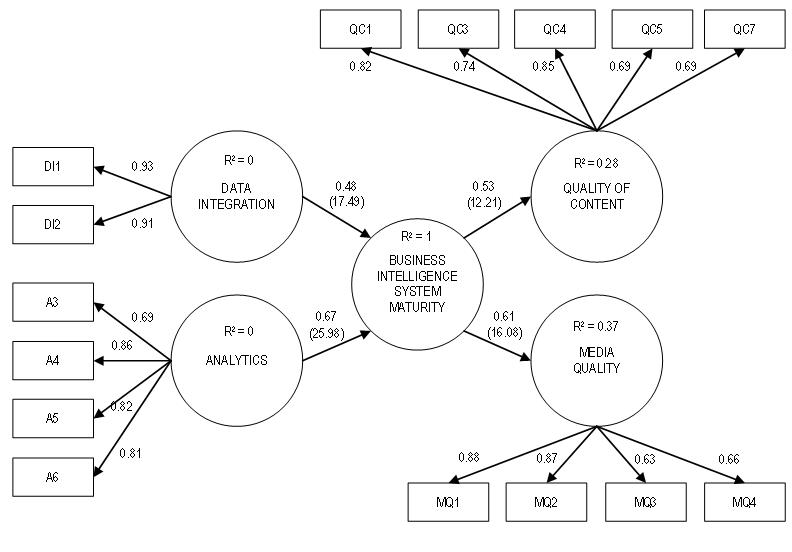

The proposed model involved nineteen measures (manifest variables) loading on to five latent constructs: (1) business intelligence system maturity; (2) data integration; (3) analytics; (4) content quality; and (5) media quality (see Table 1). The latent construct of business intelligence system maturity was conceptualised as a second-order construct derived from data integration and analytics. The specification of this as a second-order factor followed Chin's (1998) suggestion by loading the manifest variables for data integration and analytics on to the business intelligence system maturity factor. The pattern of loadings of the measurement items on the constructs were specified explicitly in our model. Then, the fit of the pre-specified model was assessed to determine its construct validity.

Data analysis was carried out using a form of structural equation modelling. These techniques provide researchers with a comprehensive means for assessing and modifying theoretical models and have become increasingly popular in information systems research as they offer great potential for furthering theory development (Gefen et al. 2000). Two different methodologies exist for the estimation of such models: maximum likelihood approach to structural equation models (SEM-ML), also known as linear structural relations (LISREL) (Jöreskog 1970) and structural equation models by partial least squares (SEM-PLS) (Chin 1998), also known as PLS Path Modelling which was chosen to conduct the data analysis in this study. PLS Path Modelling is a widely selected tool in the information technology and information systems field and is suitable for predictive applications and theory-building because it aims to examine the significance of the relationships between research constructs and the predictive power of the dependent variable (Chin 1998).

PLS path modelling was chosen for two reasons. First, we have a relatively small sample size for our research. One guideline for such a sample size when using partial least squares modelling is that the sample size should be equal to the larger of either: (1) ten times the largest number of formative (i.e., causal) indicators loading on one scale; or (2) ten times the largest number of paths directed at a particular construct in the model (Chin 1998, Gefen et al. 2000). This study used reflective indicators and hence the second rule was deemed more appropriate. The minimum acceptable sample size was twenty, derived because the largest number of structural paths directed at the construct business intelligence system maturity is two. Secondly, PLS path modelling is 'more appropriate when the research model is in an early stage of development and has not been tested extensively' (Zhu et al. 2006: 528). Further, our data have an unknown non-normal frequency distribution which also favours the use of such modelling. A review of the literature suggests that empirical tests of business intelligence systems, business intelligence systems maturity and information asymmetry are still sparse. Hence, PLS path modelling is the appropriate technique for our research purposes. The estimation and data manipulation was accomplished using SmartPLS and SPSS.

The means and standard deviations of the original variables can be found in Table 3. In the collected data set the means vary between 2.67 for A6 (dashboards, including metrics, key performance indicators, alerts) and 5.73 for CQ5 (information is contradictory). The highest means are found in content quality indicators and the lowest in the analytics construct. The means for most of the measures are around one scale point to the right of the centre of the scale suggesting a slightly left (negative) skewed distribution. Standard deviations vary between 1.24 for CQ3 (information is easily understandable by the target group) and 1.95 for MQ4 (information consumers cannot interactively access the information). Media quality indicators are those that globally show the highest standard deviations and the indicators of content quality are those with the lowest variability.

| Construct | Indicator | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Integration | DI1 | 5.04 | 1.4 |

| DI2 | 5.19 | 1.40 | |

| Analytics | A1 | 5.14 | 1.70 |

| A2 | 4.80 | 1.50 | |

| A3 | 4.27 | 1.73 | |

| A4 | 3.04 | 1.52 | |

| A5 | 2.69 | 1.85 | |

| A6 | 2.67 | 1.72 | |

| Content Quality | CQ1 | 4.67 | 1.25 |

| CQ2 | 4.95 | 1.67 | |

| CQ3 | 5.07 | 1.24 | |

| CQ4 | 4.79 | 1.32 | |

| CQ5 | 5.73 | 1.33 | |

| CQ6 | 5.18 | 1.87 | |

| CQ7 | 5.48 | 1.31 | |

| Media Quality | MQ1 | 4.62 | 1.50 |

| MQ2 | 4.79 | 1.41 | |

| MQ3 | 5.53 | 1.54 | |

| MQ4 | 4.91 | 1.95 |

We first examine the reliability and validity measures for the model constructs (Table 4). In the initial model not all reliability and convergent validity measures were satisfactory. The loadings of items against the construct being measured were tested against the value 0.7 (Hulland 1999) on the construct being measured. The manifest variables A1 (paper reports), A2 (interactive reports), CQ2 (information is not precise enough and not close enough to reality) and CQ6 (information is free of distortion, bias, or error) had weak but significant (at a 1% significance level) loadings on their respective latent constructs (A1 even had negative loadings) and were removed. Manifest variables A3, CQ5, MQ3 and MQ4 had marginal loadings (0.69, 0.68, 0.63 and 0.66, respectively) and were retained.

| Constructs | Indicators | Initial model | Final model | Estimates (initial model, all indicators) | Estimates (final model, indicators removed) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loadings | t-values | Loadings | t-values | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | ||

| Analytics | A1 | -0.38 | 3.96** | - | - | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.63 |

| A2 | 0.34 | 3.53** | - | - | |||||||

| A3 | 0.69 | 11.27** | 0.69 | 10.97** | |||||||

| A4 | 0.83 | 27.87** | 0.86 | 37.25** | |||||||

| A5 | 0.80 | 22.50** | 0.82 | 26.44** | |||||||

| A6 | 0.81 | 21.24** | 0.81 | 21.47** | |||||||

| Business Intelligence System Maturity | DI1 | 0.80 | 39.64** | 0.79 | 34.98** | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.53 |

| DI2 | 0.72 | 12.76** | 0.72 | 12.78** | |||||||

| A1 | -0.30 | 3.40** | - | - | |||||||

| A2 | 0.42 | 4.84** | - | - | |||||||

| A3 | 0.68 | 10.33** | 0.68 | 10.44** | |||||||

| A4 | 0.78 | 21.98** | 0.81 | 26.78** | |||||||

| A5 | 0.67 | 13.78** | 0.69 | 15.85** | |||||||

| A6 | 0.69 | 15.80** | 0.69 | 17.36** | |||||||

| Data Integration | DI1 | 0.93 | 87.43** | 0.93 | 80.87** | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.85 |

| DI2 | 0.91 | 35.17** | 0.91 | 35.41** | |||||||

| Content Quality | CQ1 | 0.79 | 29.50** | 0.81 | 33.29** | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.60 |

| CQ2 | 0.57 | 7.29** | - | - | |||||||

| CQ3 | 0.74 | 15.01** | 0.74 | 15.74** | |||||||

| CQ4 | 0.84 | 32.72** | 0.85 | 34.45** | |||||||

| CQ5 | 0.69 | 11.62** | 0.69 | 11.62** | |||||||

| CQ6 | 0.42 | 4.54** | - | - | |||||||

| CQ7 | 0.78 | 20.27** | 0.78 | 21.12** | |||||||

| Media Quality | MQ1 | 0.88 | 32.57** | 0.88 | 29.16** | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.59 |

| MQ2 | 0.87 | 37.61** | 0.87 | 36.24** | |||||||

| MQ3 | 0.63 | 8.52** | 0.63 | 8.85** | |||||||

| MQ4 | 0.66 | 11.26** | 0.66 | 11.28** | |||||||

| Note: ** Significant at the 1% significance level. | |||||||||||

The model was rerun once all the items that did not load satisfactorily had been removed. In support of business intelligence system maturity being hypothesised as a second-order construct, we additionally ran the model without a second-order construct. Compared to the results for this model, our second-order construct model showed R2 values not much smaller than those for the first-order construct model and indicator loadings very similar in both models. Further, other measures for reliability and convergent validity also tend to support our second-order construct hypothesis. Figure 1 shows the results of testing the measurement model in the final run.

In the final model, all the Cronbach's Alphas exceed the 0.7 threshold (Nunnally 1978). Without exception, latent variable composite reliabilities (Werts et al. 1974) are higher than 0.80 and in general near 0.90, showing the high internal consistency of indicators measuring each construct and thus confirming the construct reliability. The average variance extracted (Fornell and Larcker 1981) is around or higher than 0.60, except for the business intelligence system maturity construct, indicating that the variance captured by each latent variable is significantly larger than the variance due to measurement error and thus demonstrating the convergent validity of the constructs. For business intelligence system maturity a smaller average variance extracted would be expected since this is a second-order construct and this measure is lower than those of the two contributing constructs. Nevertheless, it should be noted that business intelligence system maturity value (0.53) is also above the 0.50 threshold, thus supporting the existence of this construct as a second order construct composed of data integration and analytics.

The reliability and convergent validity of the measurement model was also confirmed by computing standardised loadings for the indicators (Table 4) and Bootstrap-t statistics for their significance. All standardised loadings exceed (or were very marginal to) the 0.7 threshold and they were found, without exception, significant at the 1% significance level, thus confirming the high convergent validity of the measurement model. As can be seen, the removal of the four manifest variables resulted in increased Cronbach alphas, composite reliability and average variance extracted for the business intelligence system maturity, analytics and media quality constructs.

To assess discriminant validity, the following two procedures were used: 1) a comparison of item cross-loadings to construct correlations (Gefen and Straub 2005) and 2) determining whether each latent variable shares more variance with its own measurement variables or with other constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981, Chin 1998). The first procedure for testing discriminant validity was to assess the indicator loadings on their corresponding construct.

Results from Table 5 show that the loadings (in bold) are larger than the other values in the same rows (cross loadings). All the item loadings met the requirements of the first procedure in the assessment of discriminant validity.

| Analytics | Business Intelligence System Maturity | Data Integration | Content Quality | Media Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytics | A3 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| A4 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.47 | |

| A5 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.30 | |

| A6 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.34 | |

| Data integration | DI1 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.66 |

| DI2 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.47 | 0.47 | |

| Content Quality | CQ1 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.57 |

| CQ3 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.74 | 0.51 | |

| CQ4 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.85 | 0.58 | |

| CQ5 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.40 | |

| CQ7 | 0.30 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.78 | 0.74 | |

| Media Quality | MQ1 | 0.46 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.88 |

| MQ2 | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 0.87 | |

| MQ3 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.63 | |

| MQ4 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.66 | |

| Figures shown in bold indicate manifest variable correlations with latent variables that are an order of magnitude beyond other manifest variables. | ||||||

For the second procedure we compared the square root of the average variance extracted for each construct with the correlations with all other constructs in the model (Table 6). A correlation between constructs exceeding the square roots of their average variance extracted indicates that they may not be sufficiently discriminable. We can observe that the square roots of average variance extracted (shown in bold in the main diagonal) are higher than the correlations between the constructs, except where the square root is smaller than the correlations involving business intelligence system maturity and the two constructs contributing to it (data integration and analytics). This is to be expected since business intelligence system maturity is a second-order construct. Nevertheless, there is sufficient evidence that data integration and analytics are different constructs (the correlation between them is significantly smaller than the respective average variances extracted). We conclude that all the constructs show evidence of acceptable validity.

| Analytics | Business Intelligence System Maturity | Data Integration | Content Quality | Media Quality | |

| Analytics | 0.80 | ||||

| Business Intelligence System Maturity | 0.91 | 0.73 | |||

| Data Integration | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.92 | ||

| Content Quality | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.78 | |

| Media Quality | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| Figures shown in bold indicate manifest variable correlations with latent variables that are an order of magnitude beyond other manifest variables | |||||

For examining the problem of common method bias we employed two tests. For the first test we followed Park’s (2007) approach for Harmon’s single-factor analysis. The result was five factors explaining 64.2% of the variance of the data, with the first extracted factor accounting for 31.7% of the variance in the data. Since 'more than one factor was extracted from the analysis and the first factor accounted for less than 50% of the variance' (Park 2007: 39) this suggests our study's results are free from common method bias. For the second test Lindell and Whitney's (2001) method of a theoretically unrelated construct was adopted. In our study, job satisfaction was used as the unrelated construct. Any high correlation among any of the items of the study's principal constructs and the unrelated construct would signal a common method bias as job satisfaction is hardly related to the study's principal constructs. Given that the average correlation among unrelated construct and the principal constructs was r=0.17 (average p-value=2.03), this test also showed no support for common method bias.

After validating the measurement model, the hypothesised relationships between the constructs can be tested. Bootstrapping with 1,000 samples was conducted which showed that all of the hypotheses are supported with an error probability of less than 0.001. The structural model was assessed by examining the path coefficients and their significance levels. The explanatory power of a structural model can be evaluated by examining the R2 value of the final dependent construct.

As shown in Figure 1, the standardised path coefficients range from 0.48 to 0.67 while the R2 is moderate (between 0.28 and 0.37) (Chin 1998) for all endogenous constructs. It makes sense to reiterate here that business intelligence system maturity is a second-order construct, so its R2 is obviously 1. Moreover, the determination coefficients are also different for content and media quality. In fact, business intelligence system maturity explains about 37% of the media quality variation and only 28% of the content quality variation. As indicated by the path loadings, business intelligence system maturity has significant direct and different positive influences on content quality ( =0.53; p<0.001) and media quality (

=0.53; p<0.001) and media quality ( =.61; p<0.001). These results confirm our theoretical expectations and provide support for H2a, H2b and H3.

=.61; p<0.001). These results confirm our theoretical expectations and provide support for H2a, H2b and H3.

To derive additional relevant information, sub-dimensions of the second-order construct (business intelligence system maturity) were also examined. As evident from the path loadings of data integration and analytics, each of these two dimensions of business intelligence system maturity is significant (p<0.001) and of moderate to high magnitude ( =0.48 and

=0.48 and  =0.67), supporting H1 in its conceptualisation of the dependent construct as a second-order structure (Chin 1998, Zhu et al. 2006).

=0.67), supporting H1 in its conceptualisation of the dependent construct as a second-order structure (Chin 1998, Zhu et al. 2006).

Our analysis confirms the conceptualisation and operationalisation of business intelligence system maturity as a second-order construct. Through a comprehensive literature review and quantitative study of Slovenian medium- and large-sized organizations, this research reveals two dimensions of business intelligence systems' maturity: data integration and analytics. To achieve higher levels of data integration organizations need to have their data highly integrated, enabling real-time reporting and analysis and their data sources mutually consistent. When implementing data integration within business intelligence systems just employing technologies, such as extract, transform, load tools or data warehouses, is not enough. Implementing data integration also includes the execution of mandatory activities regarding data management, such as the identification of users' needs, data unification, data cleansing and improvement of data quality control at data collection. Data integration thus consists of implementing the right technologies as well as activities for data management. Achieving higher levels of analytical capabilities, on the other hand, depends upon implementing advanced analytical tools such as interactive reports, online analytical processing, data mining and dashboards.

Next, this study finds that a higher level of business intelligence system maturity has a positive impact on both segments of information quality as they were conceptualised in our model. Even if both information quality problem segments are obviously addressed with the implementation of business intelligence systems, one may expect that implementation projects are focused more on issues related to the main information quality issues in knowledge-intensive activities (i.e., content quality issues), which means the implementation of such systems should affect more content quality than media quality. The results show that the implementation of business intelligence systems indeed differently impacts on the two dimensions of information quality. However, at least at its present level of development business intelligence system maturity affects media quality more than content quality. The findings also show that the implementation of business intelligence systems explains about 37% of the media quality variation and only 28% of the variation in content quality.

Eppler's (2006) arguments assert that technology mainly influences media quality and has limited possibilities of influencing content quality. Taking these into account, one possible explanation for the observed result is that implementation projects, even those resulting in highly mature business intelligence systems, are still mostly technologically-oriented. Usually, only the data management activities that are required for implementing data warehouses are subsumed. It seems that organizations avoid more demanding data management approaches that would lead to the higher content quality of the information provided by their business intelligence systems. The unsuitability of content quality affects future uses of information and can easily lead to a less suitable business decision: analysing poor content does not provide the right understanding of business issues which, in turn, affects decisions and actions. Therefore, such approaches and focuses of business intelligence projects result in dissatisfaction with business intelligence systems and the non-use of business intelligence systems, bringing a lower success rate of business intelligence system projects.

For organizations there are some key points to consider when implementing business intelligence systems. First, the accurate definition of knowledge workers' needs. This is a difficult task due to the non-routine and creative nature of knowledge workers' work. A clear definition of their needs would ensure the comprehensiveness and conciseness of information. This emphasises the need for the simultaneous implementation of contemporary managerial concepts that better define information needs in managerial processes by connecting business strategies with business process management. The latter includes setting organizational goals, measuring them, monitoring and taking corrective actions and goes further to cascade organizational goals and monitoring performance down to levels of individual business activities. Second, improved metadata management could improve the clarity of information. Next, improved quality in data collection processes could enhance the correctness of information. Last but not least, to achieve improvements in information quality it is also important for organizations to have a proper information culture in place: organizations need to establish a culture of fact-based decision-making.

In the view of Arnold (2006), information system research on the adoption of information technology-intensive systems has provided many rich case studies about particular applications, the factors that affect successful implementation and consequent changes within an organization (for example, changes to business processes). In order to be valuable, quality information must be deployed within processes to improve decision-making (Raghunathan 1999, Elbashir et al. 2008) and business process execution (Najjar 2002) and ultimately to fulfil consumer needs (Salaun and Flores 2001). Since there is a positive relationship between perceived information quality and information use (O'Reilly 1982, Khalil and Elkordy 2005) we expect higher information quality, especially content quality, to impact on the use of information and thus generate benefits. Future research will thus need to explore other key factors determining the use of improved information quality in organizations for changing organizational analytical decision activities and business processes.

Another limitation of this research is the cross-sectional nature of the data gathered. In fact, although our conceptual and measurement model is well supported by theoretical assumptions and previous research findings, the ability to draw conclusions through our causal model would be strengthened with the availability of longitudinal data. For this reason, in future research other designs such as experimental and longitudinal designs should be tested.

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers, the Associate Editor (Professor Elena Maceviciute) and the copy-editor for their valuable and helpful comments.

Aleš Popovič is a Lecturer at the Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. He received his Bachelor's degree in Economics and Master in Information management from University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. He can be contacted at: ales.popovic@ef.uni-lj.si.

Pedro Simões Coelho is an Associate Professor at the New University of Lisbon, Institute for Statistics and Information Management, Portugal and a Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. He received his Master degree in Statistics and Information Management and PhD in Statistics from New University of Lisbon, Portugal. He can be contacted at: psc@isegi.unl.pt.

Jurij Jaklič is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia and a Visiting Professor at the New University of Lisbon, Institute for Statistics and Information Management, Portugal. He received his Master degree in Computer science from University of Houston, USA and PhD in Information management from University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. He can be contacted at: jurij.jaklic@ef.uni-lj.si.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the authors, 2009. Last updated: 1 December, 2009 |