vol. 15 no. 4, December, 2010

vol. 15 no. 4, December, 2010 | ||||

The theme of the CoLIS 7 conference is an invitation to explore the relationships between specialties and disciplines that study information. To this end, it is necessary to know the fundamental forces that shape information, binding together or separating different research traditions. My paper offers evidence that time is a force that impacts information phenomena on individual and disciplinary levels.

To begin, a framework is 'a skeletal structure designed to support or enclose something' (dictionary.com). Frameworks are the conceptual devices often employed to demark the boundaries of research specialties and disciplines. There have been many efforts to create frameworks that show the structure or unity of information science as a field; altogether there are too many to review here (Bates 2005, is a good start). It is illuminating, however, to consider two that have had a significant impact, from scholars who have pondered these matters for decades: Marcia Bates and Howard White.

At the CoLIS 6 conference three years ago, Bates presented a unifying framework for the information disciplines (2007). It was a culmination of a lifetime of creative thinking, and a direct extension of ideas in her award-winning paper, The invisible substrate of information science (1999). The conception coalesced during her editorial work on the Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, 3rd ed. (2010), assisted by historian Mary Niles Maack and an advisory board of fifty scholars.

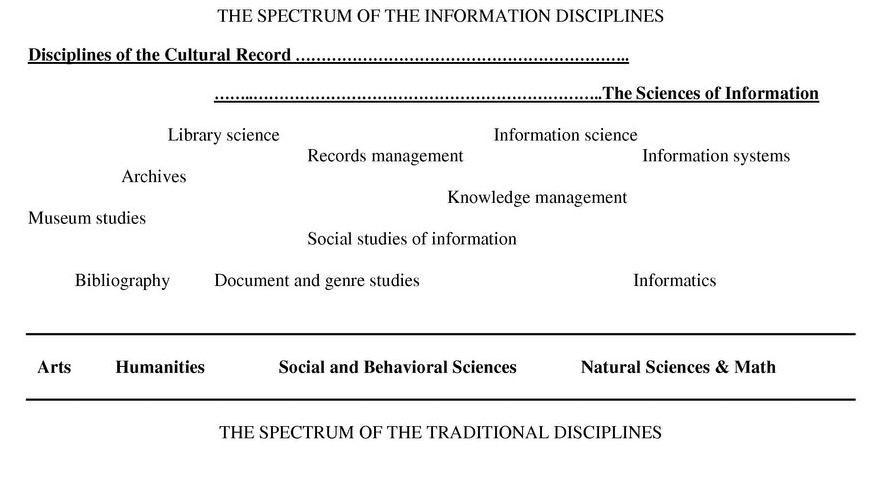

Bates's view is that within academe, the information sciences are a meta-discipline composed of eleven specialties that run above and across the traditional content disciplines of the arts and humanities, social and behavioural sciences, and natural sciences (Figure 1). Our work facilitates knowledge production in these realms; in short, we aim to, 'collect, organize, store, preserve, retrieve, transfer, display and make available the cultural record in all its manifestations' (Bates 2010: xii). Compared to the traditional disciplines, we are relative newcomers still in a formative stage. Since the information sciences are inextricably linked to the work of the entire academic spectrum, we reflect a range of ideographic and nomothetic approaches that account for our metatheoretical and methodological diversity and interdisciplinarity. While Bates's conception is centred on academe, it is a structure that she extends to include trades, avocations, and hobbies, as well.

White is another scholar with a passion to define and unify the discipline. In External memory (1995) he locates the information sciences at the intersection of people and the universe of recorded information. His Visualizing a discipline: an author co-citation analysis of information science (1998), with Katherine McCain, employs author co-citation analysis to further illuminate the conceptual and social dynamics of the field.

This well regarded study identifies twelve research specialties, namely: experimental retrieval, citation analysis, online retrieval, bibliometrics, general library systems, science communication, user theory, online public access catalogues, indexing theory, citation theory and communication theory (1998: 335). The dozen specialties coalesce around two themes: domain analysis, which includes all research into the features of literatures and information retrieval, which focuses on information access. Importantly, there is little integrative scholarship between the two realms. Indeed, information science scholarship appears centripetally flung apart and populated like Australia, with a vast unsynthesized interior. Later, in an impassioned call to action, White posted a mock-advertisement in the Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, entitled Scientist-poets wanted (1999), which petitioned scholars to creatively synthesize the central ideas of information science.

There are some similarities between these two frameworks, such as the identification of roughly a dozen research specialties and their orientation to the documentary record. The parallels are unsurprising, since Bates and White graduated from the information science programme at the University of California (Berkeley), during the 1970s, and both were students of luminaries William Paisley and Patrick Wilson. Personally, as a doctoral student, these frameworks generated eureka! moments that crystallized my understanding of information science.

While Bates's and White's frameworks are calibrated to disciplinary dynamics, they are not well synchronized with the information experience of any workaday information user. Could a lay-person make sense of either framework? How does one locate mundane information phenomena within these rubrics, such as collecting, reading, or searching for a recipe to make dinner?

The framework presented here sprang from exploratory ethnographic research into information in the hobby of gourmet cooking in America (Hartel 2007). Upon first impression, this popular, decidedly decadent pursuit may not seem a hotbed for conceptualizing information science. However, hobbies such as gourmet cooking are instances of serious leisure (Stebbins 1982, 2001), sustained, cherished, free-time activities centred upon the acquisition of special skills and knowledge.

On a social level, serious leisure and hobby realms are geographically diffuse social worlds (Unruh 1979, 1980) that share knowledge through mediated communication. In the case of gourmet cooking, this mainly takes the form of recipes, menus, cookbooks and Bernardassociated information in every possible medium. Resembling an academic research specialty, serious leisure social worlds, such as the hobby of gourmet cooking, feature information patterns that are amenable to study through a socio-cognitive or domain analytic meta-theoretical approach (Hjørland and Albrechtsen 1995; Hartel 2003, 2005), following in the tradition of studies of information behaviour among groups like academics (Talja 2005) or professionals.

My study was exploratory and it asked: What is the hobby of gourmet cooking? What do hobby cooks do? And most importantly: what is happening with information? To answer these questions I was a participant observer of the social world and I conducted twenty semi-structured interviews (Bernard 2002) with gourmet hobby cooks from Los Angeles, California and Boston, Massachusetts. Participants were recruited through purposive sampling (Berg 2000) at public culinary events and through family and friends. The interviews occurred in the cook's home and covered their participation in the hobby and the role of information. After the interview, I performed a photographic inventory (Collier and Collier 1986) to capture their culinary information collections. The fieldwork explored all kinds of culinary information in the home; however, primary attention was placed on printed resources. My fieldwork generated a rich ethnographic record (Spradley 1979) consisting of roughly several hundred pages of interview transcripts and descriptive fieldnotes, which included almost 500 photographs and diagrams.

I analysed the data using grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin 1998), facilitated by NVivo software. While reading and reflecting upon the field data, a key step was to name or code recurring concepts of interest. My codes for information activities (Appendix 1) included the anticipated 'searching for recipes' as well as surprises such as 'eating out'. In an effort to distill the findings, it was tempting to group similar activities together, following a long tradition of information behaviour models (Wilson 1999). Yet, groupings of this kind abstracted the activities and removed them from the context of the hobby and their meaningful place within the cook's narrative.

At this critical analytic juncture, I noticed that information activities have a temporal dimension and unfold at different rates in time. For instance, cooks mentioned 'making a shopping list', an information activity that was relatively quick and a key step in a hands-on cooking project. They also reported 'subscribing' for years to culinary magazines. The activity of acquiring culinary information collection sprawled across decades. In this way, time emerged as an important variable in understanding and locating each information activity in the context of the hobby.

Another analytical goal of the project was to identify the information resources used by gourmet hobby cooks. By studying the transcripts and photographs, I coded dozens of resources (Appendix 2) ranging from 'cookbooks' to 'calendars'. With a librarian's sensibility, it was tempting to group items based on format, genre, or channel. Again, doing so would detach the resource from its natural context. Here, too, I noticed how time shaped the nature of the materials and their use. For instance, the all-important 'recipe' was commonly used fleetingly during a hands-on cooking project, yet had a different role as an element of a cherished recipe collection passed down through generations.

It was my good fortune that in 2006 the theorist Savolainen was also thinking about time. In Time as a context for information seeking (2006) he reviewed more than information seeking and use studies which he scrutinized for their treatment of time. He reported that, although time is always a major variable, there is relatively little conceptual development. He goes on to describe three main approaches information behaviour researchers have taken to time. My own emerging thinking on this matter fit with his first approach: time was a fundamental attribute of gourmet cooking as a context and this effected information phenomena.

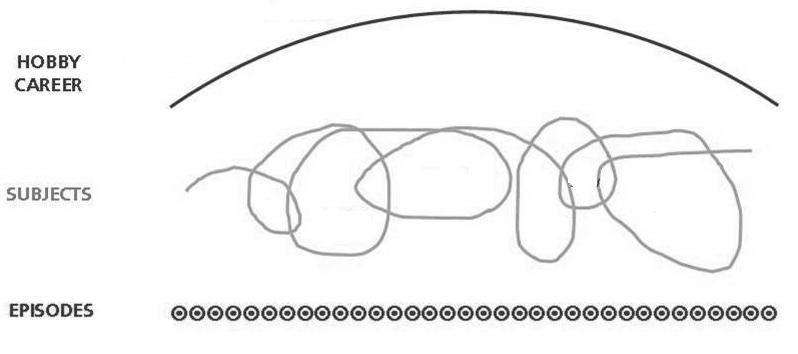

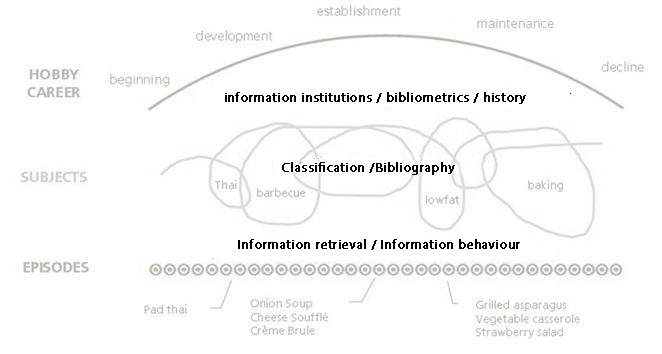

To capture these insights, I invented a framework that illustrates time as a context for information in gourmet cooking (Figure 3). It consists of three temporal arcs. The arcs represent a linked series of activities that unfold through time. This conception of the hobby resembles Sonnenwald and Iivonen's (1999) integrated framework for information behaviour, which includes eons (a long, continuous period of time), intervals (a shorter period of time with a distinct starting and ending) and episodes (a short period of time). In the framework, illustrated below, time unfolds from left to right.

There is the long-running career arc that lasts for years or decades and represents the cook's lifetime experience of the hobby. The subject arc is made up of shorter periods (weeks or months) in which a topic organizes culinary activity. Then, the episode arc entails distinct hands-on cooking projects that happen closer to real-time.

Unpacking the hobby temporally allows for a clearer understanding of information phenomena. This paper focuses on two related propositions: 1.) Each arc serves as a context for certain information activities and 2.) Each arc harbors quintessential information resources. Next, I will introduce each arc and illustrate the propositions. Later, the arcs become a springboard to entertain a time-sensitive framework of the discipline that also reflects the human information experience.

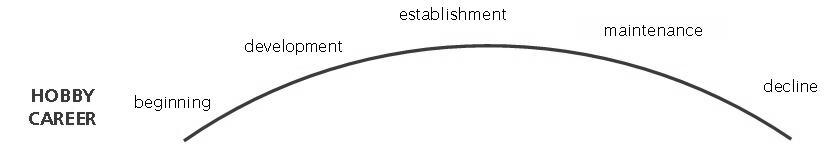

The career arc represents the path of experience taken through the hobby and it lasts years, decades, or a lifetime. This insight is not original to my study; prior research on serious leisure confirms that avid participants experience something akin to a work career, with turning points, highs and lows, and increasing competency. Stebbins has named five typical stages to the serious leisure or hobby career: beginning, development, establishment, maintenance, and decline (2001, p. 10).

Gourmet cooks told me their history in the hobby and it was easy to detect the career and its stages. To start, in beginning, cooking captures the imagination and they take an active interest in the hobby. In development, they begin to cook and acquire fundamental skills. As one cook says, 'I practiced how to dice an onion over and over again'. In establishment, cooking becomes a routine and is instituted in their life, among other things they have learned the lingo, stocked the pantry, perhaps renovated the kitchen, and attracted a circle of like-minded foodie friends. The maintenance stage is the heyday of the hobby. They are now known as great cooks, and as one reports, 'All my friends call me when they have cooking problems'. At this point, some become teachers and share their culinary passion and know-how informally with family and friends. In decline, hobby activity stops, often because of a lifestyle change or the limitations of older age.

Distinct information activities occur at this arc. The hobby career is essentially a path of learning. Each of the five stages represents a different state of culinary knowledge and skill. Hobbyists begin with minimal abilities and advance to experts. This arc is also the context for collecting and managing culinary information, activities that unfold relatively slowly and incrementally. My study shows that over the years, most hobbyists generate personal culinary libraries, constellations of cooking-related information resources and structures in the home, and an associated set of upkeep tasks (Hartel 2007: Ch. 8; Hartel in press) . Personal culinary libraries contain recipes, cookbooks, gastronomy, precious culinary keepsakes passed down from relatives and access to a wealth of online resources through a home computer. Understanding the nature of both the learning path and the personal culinary libraries requires an orientation to the career arc, what historians call the longue durée. The quintessential information resource that captures the essence of this arc is the culinary memoir, a biographical work that tells the life story of a cook.

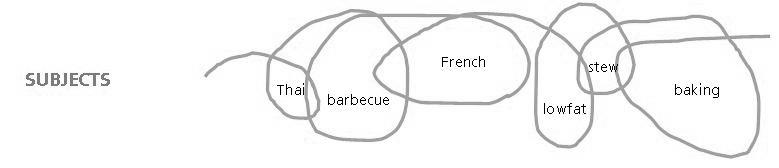

The subject arc displays how topical interests organize the hobby for weeks or months. Gourmet cooking is not pursued haphazardly. Instead, cooks select a limited area of the culinary universe and study it for a while. A subject most often takes the form of a cuisine, such as Thai or French; or, it can be a cooking style, like barbecue or baking (the subjects illustrated in Figure 5 are only examples).

Cooks reveal their experience with subjects in statements like, "That summer, I was really into French." Such a phase would be marked by reading French cookbooks, purchasing special French equipment, taking a class on French cooking, perhaps even taking a trip to Paris. Eventually, the cook masters that subject, and moves onto another one. Subjects are pictured in Figure 5 as loops of different sizes to reflect how interest varies in duration and intensity, with some overlap, as cooks transition from one to the next. The ongoing engagement with new subjects keeps the hobby interesting and fresh.

What information activities dominate the subject arc? Above all, at this scope, hobbyists read cookbooks. Several cooks in this study had dedicated weekly times for reading and favorite locations, such as a cozy chair in their den or neighborhood café. Instead of implementing recipes in the text, cooks study their composition and imagine the results, a mode jokingly called food porn (O'Neill 2003). They focus on narrative sections about ingredients, techniques, and culinary traditions. The act of reading cookbooks is an intriguing anomaly, because, structurally, cookbooks are reference books (Bates 1986), meaning they are designed for 'look up' and 'use' (to be discussed in the episode arc), not reading.

Further, when engaging a subject, cooks classify culinary information. In information science we associate classification with bibliographic control, but, on a more basic level, Kwasnik (1999) defines classification as, "the meaningful clustering of experience." When making sense of subjects, gourmet cooks reveal a faceted conception. In her own words, a cook says, "I see every cuisine from a number of angles, such as its traditional recipes, ingredients, techniques, seasonal uses. […] Each cuisine has a spectrum." Knowledgeable hobbyists use their understanding of subject structure to master new subjects more efficiently.

The quintessential information resource at this scope is the subject-themed cookbook, as in the landmark from Julia Child, Mastering the art of French cooking. It would function as a textbook for studying French cookery as a subject. When immersed in a subject, cooks do not seem content with just one text, but gather and read several that are later added to the personal culinary library. Subject-themed cookbooks contrast with more universal works such as The Joy of Cooking which encompasses innumerable cuisines and techniques.

In addition to subject-themed cookbooks, each culinary subject manifests an information domain with a constellation of books, serials, Web sites, experts, and other multimedia resources. The characteristics of these domains (meaning, for example, their size, genres and terminology) vary from subject to subject and can differ dramatically. For instance the domain of French cookery is marked by voluminous writings and precise recipes. Differently, Iranian cookery features far fewer recipes that offer inexact instructions and assume significant tacit knowledge. These diverse information environments have not been mapped by information scientists, though sociologist Newman (2001) has nicely characterized the literature of Chinese cookery. Hobbyists become familiar with the features of these differing domains and in time they can navigate and search them capably.

For the gourmet cook, subjects are topical mid-range phenomena that bring focus, structure, and dynamism to the hobby. This departs from the traditional sense of subjects as, 'the thought contents of a document' (Satija 2000: 223) to a more dynamic conception as organized activity in the context of a specific information domain. The subject arc is a very conceptual space in the hobby and it is a backdrop for the hands-on cooking discussed next.

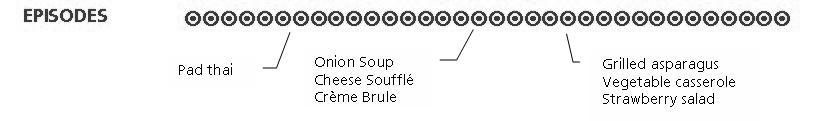

An episode is a hands-on cooking project that leads to an edible outcome. Episodes can be simple and quick, like sautéed chicken breasts, which require thirty minutes to prepare. Or, they can be more complex and laborious, such as a Thai feast which takes several days to implement. Either way, episodes are conceived by the cook as a complete, singular project. Some episodes are brand new; others are 'repeaters' drawn from a repertoire that is enjoyed again and again.

Episodes are shown in Figure 5 as circles, with some examples named. Many thousands of cooking episodes fill a hobby career (Figure 6 is not to scale). Often episodes are related to a culinary subject being pursued at the time, as when a period of interest in Greek cookery inspires an afternoon devoted to making baklava. Other times, episodes may be motivated by the events and circumstances of life, such as holidays, seasons, or a bountiful crop of tomatoes from a garden.

Each episode entails a cycle of nine distinct steps, since there is a logical and necessary flow of events in cooking. The process is too complex to describe in detail here, but is presented in Hartel (2005). Briefly, an episode begins with exploring for something to cook which generates a concept or vision, such as, 'I'll make a pecan pie!'. With a culinary concept in mind, planning happens next, which involves creating a menu, searching for recipes, and making a shopping list and a workplan, among other things. Subsequently, in provisioning, necessary ingredients and equipment are gathered. Then the hobbyist rolls up his/her sleeves for hands-on prepping, assembling, and cooking. This is the 'core activity' (Stebbins 2001) or heart of the hobby. Upon completion, the food is served, eaten, and evaluated. At the end of the episode, the cook is poised to begin again.

Once the steps within the episode are illuminated, we can more precisely identify, locate, and analyse information activity. For instance, searching for recipes happens during the planning stage and resembles a berrypicking search (Bates 1989) beginning at home in the personal culinary library. Prepping-assembling-cooking feature a particular type of information use in which recipes are repeatedly consulted to determine next steps. During evaluating, the hobbyist often asks others for input on the outcome, and then mark notes on the recipe. The important point is, a distinct constellation of relatively quick information activities function at the level of the episode. The quintessential information resource at this arc is the recipe, which steers much of the activity.

This research project discovered that unpacking the hobby of gourmet cooking temporally allows for a clearer understanding of information phenomena. To review, the hobby career lasts a lifetime; it is the broadest measure of learning and each of its five stages has a different knowledge state as cooks advance from novices to experts. This is the context for the ongoing, incremental effort of collecting and managing culinary information in a personal culinary library. The reality at this arc is captured in a culinary memoir. At the subject arc, temporary topical interests organize activities that can last weeks or months. Instead of proceeding scattershot, cooks meaningfully cluster (or classify) their experience. The primary way to study culinary topics is to read subject-themed cookery books. Each culinary subject is an information domain with distinct patterns and characteristics. Finally, the episode arc harbours hands-on cooking projects that entail nine sequential tasks. Many different, relatively quick, information activities occur, such as seeking, using, and evaluating culinary information. The quintessential information resource of the episode is the recipe-the instructions for cooking.

This framework, based upon time, helped in answering my original research questions: What is the hobby of gourmet cooking? What do hobby cooks do? And, what is happening with information? In the tradition of ethnography, the findings are context-bound to the gourmet cooking social world, but broader implications are hard to resist. Next, the arc framework is used as a springboard to propose a temporal framework for information science.

The three temporal arcs spark the notion that time influences the research areas of information science. To acknowledge, this leap takes empirical data drawn from individuals and projects it to the level of a discipline. It is admitted that several, though not all, specialties in information science appear to have an affinity for one arc, and, as such, this framework is not offered as comprehensive. Still, for certain research traditions, an arc is where, or, more precisely, when, their research concerns or problems come into sharpest view.

The career arc spans decades and, at the individual level, it involves lifelong learning and information collecting. On a disciplinary plane, this is the concern of information institutions such as libraries, archives and museums charged with the provision of materials for perpetuity. To illustrate, the mission statement of the Library of Congress is to, 'sustain and preserve a universal collection of knowledge and creativity for future generations'. This arc also harbors scholarship within White and McCain's 'domain analysis', namely bibliometrics, which considers the evolution of literatures over extended periods of time. Indeed, White and McCain's study examined a twenty-four-year span of co-citation patterns. Here, too, are our field's historians who naturally take a long view.

For gourmet cooks, the subject arc involves reading for weeks or months in order to master a topic, in an effort to understand its facets and relationship to other culinary traditions and practices. Within information science, this is the site of classification, research similarly concerned with subjects and their dimensions. At this arc, the distinct information domains that coalesce around subjects become apparent, which mirrors the traditional heart of the field: bibliography. Perhaps without realizing it, scholars in these traditions help people succeed with medium-term intellectual pursuits.

The episode arc is the vital realm of real-time information experience. This is the home of specialties such as information retrieval. Most forms of information retrieval occur in instances lasting seconds or minutes. A major concept in this area, relevance, is a situational assessment that is difficult to imagine stretched over any longer time span. Research into information behaviour also resides at this arc. Here, the predominance of studies focus on a singular bounded transaction, whether a student's research project (Kuhlthau 1993) or a work task (Byström and Hansen 2002). The breakthrough ideas of information grounds (Pettigrew 1999) and information encountering (Erdelez 1997), are at heart temporal, temporary, usually fleeting information events.

There are important implications of this temporal framework of information science. If research specialties orient their attention to information phenomena at a single arc, there is a risk of adopting an incomplete view of the user experience. When engaging information, people are impacted by contextual forces from every arc. A gourmet cook's quick recipe search is shaped by the informational characteristics of the particular episode; both the subject and career stages are at play. It is a challenge to study and understand information phenomena on so many cascading levels.

Music, a most temporally-aware discipline, provides a closing reflection for this paper. Information and music are cousins, of sorts, because both unfold in time when experienced by a user. Sometimes a gathering of information scientists, like any CoLIS conference, contains unsynchronized voices and perspectives. Perhaps this is because our specialties engage information in different time frames, or tempos. Some focus on the incremental accumulation of materials at information institutions, or the gradual shifts in citation patterns within literatures; efforts akin to a waltz. Others orient to a faster tune that coalesces, dissolves, and reorganizes anew after a short while; like jazz improvisation. A vocal majority explores real-time information problems and solutions, which pulse like contemporary trance music. Despite being in the same key (information), when played altogether the three tunes generate a cacophony. While it may be impossible to synchronize information science research into a singular harmony, we benefit by knowing the reason for the noise.

Greg Leazer, Sanna Talja, Robert Stebbins, Reijo Savolainen, and Jarkko Kari provided essential support and guidance throughout my culinary research. Thanks also to Joseph Hartel for comments that improved this manuscript, and to Ashleigh Burnet for excellent copyediting.

Jenna Hartel is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Information, University of Toronto. Her research is organized around the question: What is the nature of information in the pleasures of life? She is investigating this matter through the concatenated study of information phenomena in serious leisure -- cherished, information-rich pursuits such as hobbies. Her empirical research explores the content, structure, and use of leisure information on personal and social levels, and her theoretical work aims to characterize the nature of information in leisure realms. She can be contacted at jenna.hartel@utoronto.ca

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

Sample of codes used for information activities:

| traveling receiving (information as a gift) dining with other cooks eating out (studying menus, foods) visiting a market blogging browsing contemplating watching television reading (cookbooks, gastronomy) taking cooking classes teaching cooking | consulting talking (about cooking) publishing subscribing (to magazines) designing recipes or menus comparing (recipes) searching for recipes checking (a recipe) displaying (recipes) translating listing (ingredients) |

Sample of codes used for information resources:

| cookbooks magazines newspapers newsletters recipes reference soures fund-raising cookbooks ephemera (calendars, brochures) gastronomy writings pictures ratings and rankings lists timelines journals (diaries) |

display boards stories experiences people (family, friends, chefs) fairs cooking classes restaurants trips public library parties retail stores web pages e-mails television |

© the author, 2010. Last updated: 22 September, 2010 |