vol. 15 no. 4, December, 2010

vol. 15 no. 4, December, 2010 | ||||

The aim of the study was to investigate the information practices of peri-menopausal women and to relate the findings to an established model of everyday information practices. There is currently debate about the meaning and appropriateness of the terms information pratices and information behaviour (Savolainen 2007; Wilson 2009). The debate is still open and the term information practices will be used in this paper for consistency with McKenzie's original model.

A large number of information-behaviour or practice models have been generated by information researchers but many have done little to add to the generation of theory. For Bates (Bates 2005), models are a tool in the development of theory but they must be tested for validity and it is this process alone that can turn them into true theory. However, few existing models are being tested and their role in the process of theory generation, therefore, is restricted. Such models are frequently based on small studies that are context-bound. To consolidate the research base and move it forwards, a process of testing models in different contexts should be encouraged.

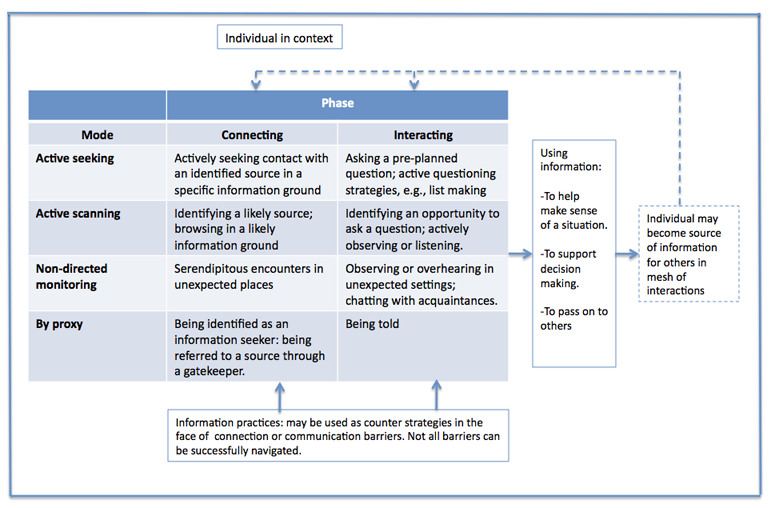

This study, though admittedly small-scale and context-bound itself, takes a step towards redressing the situation by testing McKenzie's model of information practices in everyday life information seeking in a different, yet related, context. McKenzie studied the information practices of 19 Canadian women pregnant with twins. She devised a two-dimensional model of everyday life information-seeking which sought to 'reflect the idiosyncracies of multiple pregnancy as an information-seeking context and to identify the patterns and concepts that might translate to other contexts' (McKenzie 2001). McKenzie charts her research from an initial intention to explore the characteristics of two modes of information practice (active and incidental information-seeking), through a realization that data emerging from accounts were so rich that the original dichotomous goal seemed inadequate, to the development of the final model (Figure 1) which portrayed four modes of information practice:

Each of these modes could itself figure in either of two stages of the information process: connecting with and interacting with sources of information.

When making connections (Phase 1 of the model), participants described practices involved in identifying (or being identified by) and making contact with (or being contacted by) potential sources and barriers that could inhibit this process. After initial contact was made with a source, the quality of the actual interaction formed the second phase of the model. McKenzie suggested that information practices (e.g.. asking direct questions or being persistent) could be used as counter-strategies to combat barriers. In a subsequent publication McKenzie (McKenzie 2002) expanded on the concept of connection and communication barriers and identified how the communication-process between pregnant women and their information sources could break down: failure to ask questions; disclosure barriers (source unable or unwilling to disclose an answer); lack of realization or comprehension; and connection failures during the communication process.

McKenzie viewed twin pregnancy as an unexpected situation in which previously-existing networks of formal and informal help and information might not be sufficient to meet a woman's needs. From the literature and the findings of her own study she identified two interpretative repertoires that described the characteristics of multiple pregnancy: the first focussing on the commonality of experience (the fact that all women in such a situation are likely to encounter similar challenges and attitudes), and the second on the uniqueness of the experience (each woman will have her own experience of the pregnancy).

The menopause transition provides a contrasting, yet related, context in which to test the model. Komesaroff (Komesaroff 1997) notes parallels between the states of pregnancy and menopause: each is experienced by women; is culturally and biomedically defined in relation to notions of reproductive femininity; is medically managed in industrialized countries; and is commonly described in hormonal terms. Furthermore, like twin pregnancy, the menopause reflects McKenzie's interpretative repertoires of commonality of experience (the menopause occurs for the majority of women) and individuality (as for pregnancy, each woman's experience of the menopause transition is unique to her).

Despite these similarities, there are notable differences between the two states, with contrasting cultural attitudes towards pregnancy and the menopause. Western cultures frequently imbue the menopause with negative associations reflecting attitudes towards ageing in general and, according to many feminist writers, towards ageing women in particular (e.g., Greer 1991, Martin 1997, Oakley 2007). Unlike pregnancy the menopause is not necessarily visible to others and in fact many women strive to keep it a private matter. Furthermore, although the menopause transition usually has a finite duration it is often longer than that associated with pregnancy and may last for several years. For a woman experiencing her menopause transition, the time-lines of care may not be as distinct as those experienced in pregnancy: her needs may change over time and levels of and approaches to care may depend on a woman's personal values and on her encounters with individual members of the healthcare professions.

In all, thirty-five interviews were carried out and one further participant from the menopause clinic cohort provided a response by mail. All interviews were conducted in 2004/2005. Of the interviews, twenty-six were with patients of the menopause clinic (recruited through their participation in the questionnaire-based service-audit carried out for the clinic); seven were with staff at the care-home; and two were with the women from the same geographical area as the clinic but who had not attended it.

In seeking to design a study that would support the testing of an existing model, precedents were sought in the literature. Despite the large number of models and the acknowledgement by authors that their models/frameworks should be tested and refined across a range of contexts (Wilson 1999, Johnson 2003), there is little evidence of testing. Research by Beverley et al. (Beverley et al. 2007), published too late to inform the design of the menopause transition study, tested Wilson's (Wilson 1999) revised model of information behaviour and that of Moore (Moore 2002) in the context of the information behaviour of visually-impaired people seeking health and social care information. A study by Veinot (Veinot 2009), which compared findings from interviews with people with HIV/AIDS and their friends and family members to Haythornthwaite's (Haythornthwaite 1996) theory of network-based information processes and Talja and Hansen's collaborative information behaviour framework (Talja and Hansen 2006), was likewise published too late to be reflected in the study design.

In a similar approach to that taken by Beverley et al., the aim of the menopause transition study was not to replicate McKenzie's methods exactly but to find a complementary approach that would be appropriate for the subject whilst permitting analysis in the context of McKenzie's findings. The data collection methods employed by McKenzie (McKenzie 2001) were face-to-face interviews and periodic check-in telephone interviews which formed the basis of a research diary. The diary was in turn used to structure follow-up interviews. The scope of the menopause study did not permit the charting of information practices throughout participants' menopause transitions and one-off in-depth interviews were identified as the most appropriate method. Given the different timescales between pregnancy and the menopause, a follow-up interview after a short interval would have been unlikely to have produced many new instances of relevant information practices.

In a further departure from McKenzie's original methodology, the free-text responses to the service-audit questionnaire were included if they were relevant to the wider discussion of information practice. The service-audit questionnaire was distributed to 216 registered patients of the NHS menopause clinic, of whom 199 returned completed questionnaires. The majority of the questions focussed specifically on the service provided by the clinic and therefore had limited value for the wider discussion. Some free-text questions however did elicit responses that could be incorporated into the information-practice discussion (e.g. responses to the question 'Have you ever had problems finding the menopause advice you needed?').

The interview guide took the form of an initial invitation for participants to talk about their experience of the menopause. The remaining topics were used as prompts and were intended to help interviewees focus on their information practices. To ensure that participants were given the same opportunities as McKenzie's interviewees to comment on their information practices, similar topics to those raised by McKenzie were included (e.g. whether participants had ever found information that conflicted with something they knew or thought, and whether there was anything they worried about but had not asked about). Topics identified from the piloting process as being relevant to the menopause were also included, for example at what point women decided they needed to look for advice or information about the menopause and where they would be most likely to turn for support. Despite accepting a need to be guided by McKenzie's interview guide to ensure a level of comparability between findings, it was important not to direct interviewees actively or inadvertently towards giving similar answers. For this reason participants were given the opportunity to express themselves freely as they told their menopause stories and a flexible approach was taken to asking additional questions.

The original aim was for all interviews to be face-to-face but logistical problems precluded this. The seven care-home interviews were carried out face-to-face but the twenty-eight remaining interviews were by telephone. There are acknowledged disadvantages to telephone interviewing, especially for in-depth qualitative interviews, since it clearly limits opportunities for the researcher to observe the interviewee and pick up non-verbal clues that might help interpretation (Bryman 2001; Frankfort-Nachmias and David 1996; Payne 2004). Furthermore, it is possible that interviewees may be more reticent about giving sensitive information via the telephone, and feminist researchers point out the value of face-to-face encounters which foster relationship-building (Finch 1993, Oakley 1981). Payne (Payne 2004), however, suggests that a lack of physical presence may be an advantage in that respondents are less likely to react to an interviewer's appearance and may feel safer in an anonymous relationship. Comparison of the experiences of face-to-face interviews and telephone interviews suggests that in the case of the menopause study the quality of the experience and of the information provided was not greatly influenced by the method of interviewing. The use of telephone interviews allowed participants the flexibility to choose the time of their interview (often in the evening to fit around family and/or work commitments). A tape recorder was used, thereby allowing the researcher give full attention to the interviewee throughout. Every attempt was made to remain sensitive to the need to give telephone interviewees time to think through their replies and any points of uncertainty were clarified since there were no visual clues to aid interpretation. There was little variation in the depth of interview achieved by either method although, perhaps surprisingly, several of the face-to-face interviews were considerably shorter than the telephone interviews. This was most likely due to variables other than the method of delivery: menopause clinic participants had all sought professional help in dealing with their menopause whereas some care-home participants stated that they had relatively few symptoms and felt they had little to say about their menopause experiences.

The data from the service-audit questionnaires were analysed using a spreadsheet to provide simple descriptive statistics that satisfied the requirements of the clinic evaluation. Responses to open-ended questions were then included in the information-practices analysis where appropriate. Interview transcripts were analysed in a process of thematic coding using NVIVO qualitative data analysis software. Interviews were coded first for themes that emerged relating to experiences of the menopause, attitudes towards it, and information practices. A second round of coding focussed on categories relating to McKenzie's model (e.g., for instances of specific information practices such as examples of active scanning activities).

Data from the menopause study were then applied to McKenzie's model, a process which presented three main challenges:

Limitations of the study included that fact that, along with many similar studies, this was small-scale. Most interviews were with menopause clinic patients who had therefore experienced symptoms severe enough to warrant seeking help. Attempts were made to redress this with a cohort from non-clinic environments. Furthermore, participants' accounts frequently spanned several years which could impact on recall. This was in contrast to McKenzie's participants whose accounts featured more recent events. This last point illustrates one of the challenges of attempting to test an existing model. As well as dealing with the other issues encountered during analysis (the need to understand the original researcher's decision-making and the question of how to deal with elements that do not fit the model), a researcher must give careful consideration to the study design: how far should the new study reflect the original in terms of, for example, survey instruments and size of sample? Beverley et al. explain that their study-design was based on the findings of a literature review and informed by consultation with visually-impaired people and the suggestions of advisors. They do not specify, however, whether the study design was influenced by those of the researchers whose models they were testing (Beverley et al. 2007). The decision taken in the menopause study was to attempt to find a balance between allowing participants to give their views freely in a way that would be true to the new context whilst ensuring that data would have validity when applied to the model.

In common with findings from other studies of midlife women (e.g., Im et al. 2008, Price et al. 2008), participants had mixed feelings about the menopause transition. The themes that emerged from the analysis can be loosely grouped into four categories: making sense of the situation; interpretative repertoires of the menopause; receiving and providing advice, information and support; and challenges in encounters with information and support. These are discussed below.

Participants viewed the menopause as 'part and parcel of life' and saw it within the context of their whole lives. For several this interpretation influenced decisions on managing the menopause as they sought out natural ways of controlling their symptoms. Despite this underlying acceptance of the menopause as something natural and inevitable, it could still be unsettling and uncomfortable and could affect participants in ways beyond purely physical symptoms. Several mentioned feelings of dread or lowness that took away their enjoyment of life and many found themselves coping with the menopause alongside emotional and practical challenges in their personal lives (e.g., ageing parents, adapting to life as an older mother). Many feminist writers (e.g., Greer 1991; Campioni 1997; Gullette 1997) urge women to view the menopause as a watershed, a time to move towards an older, stronger self. However it can be a challenging time for women, and renegotiating self-image is not necessarily easy. Participants spoke of striving to find a balance between not wanting to stay permanently young, whilst not wishing to be old. Some explained that menopausal women can feel 'a bit of a failure' and that there is a common perception that midlife women who do acknowledge their problems are simply seeking attention.

McKenzie's (McKenzie 2001) contrasting interpretative repertoires that characterize pregnancy (commonality of experience or uniqueness of the individual) are equally valid for the menopause. Participants in the menopause study saw their experiences as enmeshed with those of other women and actively sought out information about other women's menopause stories to provide context and validation for their own. They referred to the experiences of family members and friends and to anecdotes. They would particularly look to their mothers' experiences to attempt to predict the course of their own menopause. However, whilst acknowledging that it is an essential experience of womanhood, interviewees were aware that each woman's menopause transition was entirely her own. Women who experienced few or relatively mild symptoms considered themselves lucky and were perceived as such by their less fortunate peers. Interviewees sought reassurance from the experiences of others, using the comparison to gauge their own progress through the transition whilst accepting the uniqueness of their own situation since 'everybody is so different'. Participants who had experienced an early menopause whether natural or surgically-induced were particularly at risk of feeling different and isolated. The decision of how to manage symptoms provided a further example of the individual response to the problem with some women choosing hormone replacement therapy and others turning to complementary and alternative medicine approaches.

Evidence from the literature shows that women value informal, interpersonal sources of information and advice (e.g., Meadows et al. 2001, Ankem 2007, Avery and Braunack-Mayer 2007). Participants in the menopause study confirmed this and several explained that they relied heavily on the support of family and friends. In common with participants from other studies (Suter et al. 2007, Price et al. 2008), participants expressed a desire for reassurance that their experiences were normal. This validation could come from interpersonal encounters but participants also found it through hearing or reading accounts of other women's experiences. The exchange of advice and support could be reciprocal. Women sought out the menopause stories of others but recognized that they too had a role in providing support. Some had actively assumed this role through involvement in support networks (an online early-menopause forum) or by becoming known as an expert in their social network and passing on information to friends. Interviewees revealed a mesh of interwoven encounters with information sources that could take place over several years, as their symptoms and personal situations changed and as they sought to compare and confirm information (especially in the light of frequent and widely-reported developments in the debate about the risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy). They displayed both active and passive information practices as they monitored the environment for relevant information and then contacted health- or alternative medicine-professionals for specific advice as needed.

Participants stated that they often ended up feeling as though they were 'running round in circles' and that they struggled to get the help they needed. Although some women reported good relations with health care professionals many felt that the health care system did not adequately meet their needs. They commented on the limited time available in a primary-care appointment ('The feeling I often have is that my problem must fit in with the five minute allocation') and for this reason many commented favourably on the community menopause clinic which provided the opportunity for a more thorough investigation and for options to be discussed in full. This was viewed as confirmation that a woman's problems were being taken seriously and that she was being listened to. Some participants also felt themselves to be disadvantaged by individual healthcare professionals' attitudes towards hormone replacement therapy and complementary or alternative medicine, or commented that they had received conflicting advice about therapy from different medical sources. In an environment in which women are regularly exposed to opposing views about the risks and benefits of hormone treatment and complementary medicine through the media and personal contacts, lack of consensus between medical practitioners adds to uncertainty that can ultimately erode confidence and trust.

Choosing to test a model in a different yet related context proved a challenge and one for which there were few precedents and little guidance in the literature. Most of the examples of information practices that emerged from the menopause study could be positioned within McKenzie's model. At times, however, the decision about exactly where to place them was not straightforward or there were differences in the amount of data that could populate categories. An example of this was the category of 'Non-directed monitoring' in the 'Interaction' phase of the model. McKenzie's study provided examples of out of the blue encounters in situations where participants were not expecting to find information (e.g., watching a parent manoeuvre a double push-chair). Interviewees found that the visibility of twins-pregnancy facilitated such encounters. In the menopause study there were hardly any examples of unexpected encounters. The fact that the menopause is less visible to the outside world may have inhibited opportunities for observing others. Another factor may have been that the menopause is still something many women may wish to be discreet about. A woman is therefore less likely to have opportunities for overhearing conversations about the menopause out of the blue (unless she is in an environment where she would expect to find menopausal women which would then constitute an example of Active scanning in McKenzie's model); she is also possibly less likely to chat about her menopause to acquaintances (as opposed to friends) such as, to use an example from McKenzie's study, a colleague's wife.

Table 1 provides examples of how data from the menopause study were applied to McKenzie's four modes of information practice in the two phases of Connection and Interaction with sources.

| Connecting with sources (McKenzie's definition) | Examples from menopause study | Interacting with sources (McKenzie's definition) | Examples from menopause study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active seeking |

Systematic known-item search. Seeking out known source. Asking pre-planned question. Planning question strategy. |

Contacting NHS Direct after hearing or reading about a study. Making appointment with community menopause clinic to ask about symptoms. Writing to The Amarant Menopause Trust. |

Asking a pre-planned question. Active strategies (list-making or questioning techniques; counter-strategies to barriers). |

Negotiating with healthcare professionals to achieve desired outcome. Taking information to encounter. Taking the initiative if anticipated contact is not made. Asking different people about the same issue. |

| Active scanning |

Semi-directed browsing in likely locations. Systematic observation of behaviour Identifying opportunities to ask spontaneous questions. Active listening to conversations in likely locations. |

Spotting a notice about the menopause clinic when attending a chiropody appointment. Asking medical representatives at work. Browsing a bookshop or library. Carrying out a general Internet search. |

Identifying an opportunity to ask a question. Actively observing people or behaviour, or listening to conversations in likely locations. |

Listening to colleagues talk about the menopause. Taking the opportunity to talk to other women in hospital. Asking health-food shop staff whilst shopping for something unconnected with menopause. Chatting to practice nurse whilst attending for a different health issue. |

| Non-directed monitoring |

Serendipitous encountering of a source. Accidentally overhearing a conversation. Unexpected encounters e.g., with friends. Regular activities to stay informed without actively seeking information. |

Saw community menopause clinic whilst walking by. Read about clinic in local newspaper. Spotting useful information in the media. Meeting a source through a dress-making business. |

Observing behaviour or physical characteristics in unexpected settings. Overhearing conversations. Chatting with acquaintances. |

Finding a useful Website after hearing about it by chance on the radio. |

| By proxy |

Making contact through initiative of another agent. Being identified as a potential information seeker by a potential source. Being referred to sources by other people. Making connections through intermediaries or gatekeepers. |

Being referred to clinic by Family Planning staff. Being told about the clinic by a friend or colleague. Swapping books with friends. Having a friend recognize problem and offer support. |

Being told (e.g., through other women's stories; diagnostic information from professionals; other people's advice/opinions; offering of unsolicited advice). |

Hearing information during sessions held at primary care practice. Being advised to try hormone replacement therapy by a friend. Exchanging menopause stories. Receiving diagnostic information from professionals. Using complementary or alternative medical treatments recommended by family and/or friends. |

McKenzie's aim was to create a model that preserved the fluidity of women's interactions with sources of information and support. The concept of fluidity was particularly strong in the accounts of menopausal women. The great value placed on by-proxy interactions for this group of women extended beyond being told things by other people into an active exchange of information and support. Unlike McKenzie's participants, who were easily identified as information seekers, participants in this study moved in a more complex environment in which they engaged in exchanges of mutual support. Such exchanges could be informal, through friends, colleagues or family members, or could occur in a more structured way such as involvement in an online forum.

As women's journey through the menopause progressed, they themselves became acknowledged sources of information for others. The fact that the pregnant women in McKenzie's study turned to other women for advice indicates that they in turn could have a potential role as sources of information. However. this did not appear to emerge as a strong theme from the study. This may be because of the relative rarity of twin-pregnancy which limited opportunities for exchange of information with other pregnant women or to the fact that pregnancy is a relatively short period of high information-seeking activity and with a high level of involvement with professional healthcare providers. It is possible that the pregnant women would be more likely to be identified as authoritative sources of information in the future, after their babies were born when they would be perceived as women who had 'been through it', as was the case for McKenzie herself in her interaction with participants (Carey et al. 2001).

In another recent study in which findings have been applied to existing frameworks, Beverley et al. (Beverley et al. 2007) applied Moore's (Moore 2002) model of social information need and Wilson's (Wilson 1999) model of information behaviour to the information behaviour of visually-impaired people seeking health and social care information. The authors were able to build upon elements of Moore's model (ranking Moore's concept of information clusters by relevance to the participants in their own study) but found that the model did not account for all the intervening variables acknowledged in Wilson's model and which emerged as important in determining information behaviour among people with a visual impairment. Veinot's (2009) study focused specifically on the concept of information exchange in everyday-life information behaviour and identified several network-mediated processes that facilitated access to HIV/AIDS information in everyday life. The author related her findings to Haythornthwaite's network exposure concept and to Talja and Hansen's (2006) collaborative model. Everyday-life information behaviour was found to be more voluntary and loosely coordinated than had previously been described in workplace-based studies and with a stronger affective element. Veinot concluded that the concept of network-mediated exposure that emerged from the HIV/AIDS study had less in common with Haythornthwaite's concept than with other information practices such as those apparent in McKenzie's model.

The aim of the menopause study was to apply McKenzie's framework in a different context to test its transferability (rather than generalisability, as the model was based on qualitative research). Therefore, a complementary approach was taken, seeking not to replicate the original study exactly but to design a study suitable to the new context yet that would ensure that data gathered would be suitable for applying to the framework. Applying the findings to McKenzie's model demonstrated that the model is fundamentally dependable and flexible enough to permit adaptation to a different context. However, there were challenges inherent in the process. Some were the natural result of attempting to use a researcher's model without access to her decision-making process and others stemmed from the particularities and subtleties of the change of context. Järvelin and Wilson (2003) developed a framework that can be used for judging the merits of a conceptual model or assessing the relative merits of two competing conceptual models. McKenzie's model was considered against Järvelin and Wilson's criteria of simplicity, accuracy, scope, systematic power, explanatory power, reliability, validity and fruitfulness, but using appropriate qualitative validity criteria (Lincoln and Guba 1985): credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability.

McKenzie's model is simple in design and easy to interpret in the context of her own research but attempting to fit examples from a different context was more complex than anticipated. The model's scope was narrow, as was the menopause study scope, but applying the model in a wider range of contexts should broaden the scope over time. The inclusion of the concept of interaction permits the discussion to move beyond information seeking and finding into what happens once interaction with a source of information has been initiated. McKenzie's concept of 'interaction' did not completely meet the needs of the findings from the menopause study. There is little scope in the model for the idea of women mutually exchanging information or of becoming themselves sources of information and advice which emerged from this study. The model is therefore mostly dependable (reliable) and credible (valid) in that it can be reasonably successfully applied to results from a study in a similar context and undertaken from a similar standpoint, but it does not take account of the full range of possible situations when presented with a different set of data.

McKenzie deliberately avoided a linear representation of a systematic search process with the associated implications of a logical progression and sought to develop a flexible model that would preserve the fluidity of the information practices described but that would systematically describe the practices and the process. The simplicity of the model enhances its explanatory power, yet attempts to apply data from a different context revealed that it is not easy to predict how data from a different study would fit within it. There are some difficulties, therefore, in the confirmability of the model's concepts. Järvelin and Wilson's final requirement for a successful conceptual model is fruitfulness by which they suggest that such a model should be able to suggest problems for solving and hypotheses for testing. In the context of the data from the menopause, it is the areas that did not fit so comfortably with the model that would best indicate problems to be investigated.

It would potentially have been simpler to take the data from the menopause study and create a new model to fit those data neatly, rather than face the challenges of applying them to an existing model. Likewise it would have been easier to design the interview guide without the need to take a stand on whether to base it on McKenzie's interview guide. However, the research base would not benefit from another model based on a single small-scale study. Established models should be tested and built upon to develop meaningful systems that are robust enough to be transferred across contexts. Figure 2 therefore presents a version of the McKenzie model of information practices in everyday life information seeking extended to allow for the findings from the menopause transition study. The original model acknowledges that the quality of the information encounter and what happens within it is as important as the initial connection with a source. The extended model takes account of what happens to the information after it is acquired, i.e. how it is used. It also takes account of the dual role of the individual who may in turn become a provider of information. A further change to the original model is the acknowledgement that not all barriers may be successfully negotiated, for example, women from the menopause study had questions about hormone replacement therapy that could not be resolved because medical science is not yet able to provide the answers.

Applying the model of information practices in everyday life information seeking in a different context has demonstrated that there is value in the testing of models. The model was sufficiently transferable and flexible to permit adaptation to a different context. However, there were elements of the new context that provided a richer and deeper interpretation of the categories within the model and suggested ways in which it could be extended (i.e. by taking account of women's more complex relationship with information in which they themselves may become sources of advice and by adding further depth to McKenzie's description of barriers and counter-strategies). Further testing in a different context again, perhaps unrelated to women's health, should provide further insights into how the model could be consolidated and move towards the development of a more generic model of everyday information practice. Given the limited precedence, there is currently little guidance for a researcher attempting to test an existing model. It is hoped that discussion of the challenges faced in this study will help future researchers wishing to attempt the process.

I would like to extend my thanks to my supervisor, to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and to all those who participated in the study. I would also like to thank the reviewer(s) for their constructive and useful comments on the paper.

Alison Yeoman is a Research Officer in the Department of Information Studies, Aberystwyth University. She has worked on several qualitative research projects, mainly in the field of health information, and completed her PhD in 2009. She can be contacted at ajy@aber.ac.uk

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the author, 2010. Last updated: 10 December, 2010 |