vol. 16 no. 1, March, 2011

vol. 16 no. 1, March, 2011 | ||||

Information behaviour is defined in many ways. Wilson (1999) suggests that information behaviour is concerned with three components: information needs, information seeking, and information use. While much has been written on information needs (see for example, Taylor (1968), Ingwersen, (1994) and information seeking (see for example, Belkin et al. (1982), Kuhlthau (1993), less has been reported on the ways in which information is used. While we discuss information use, it is often interpreted as the user's situation or context when they are identifying an information need (i.e., problem) and then applying the information to the specific problem. Research in this area typically focuses on sense-making and is grounded within a cognitive perspective that focus on the role of conscious thought and feelings (Albright 2010). A cognitive perspective is useful for understanding that which lies within the user's cognition, i.e., conscious control, and that they are able to describe how they process information and make judgments. It is based on the idea 'that any processing of information, whether perceptual or symbolic, is mediated by a system of categories or concepts which, for the information-processing device, are a model of his world' (de Mey 1977: xvi-xvii). A cognitive perspective views the human mind as an information processing machine, with three primary processes: 1) sensory input, 2) the internal processing (i.e., thinking); and 3) output (i.e., verbalization). The root of much information behaviour theory centres on these three processes. Cognitive psychology historically saw these three processes as independent, but has recently considered them to be interdependent. The role of emotions has also become of greater interest, although emotion is still considered only at the level of conscious awareness.

Much of our mental life, however, lies outside the realm of conscious awareness. Our mental life includes thoughts, feelings, motives, drives, wishes, and desires. These underlying thoughts and feelings mean 'that people can behave in ways or develop symptoms that are inexplicable to themselves' (Westen 1998: 334). While information behaviour research has recently recognized the role of emotion in the interaction between user and information, it has not given sufficient consideration to the role of the unconscious in that interaction. The purpose of this paper is to consider a psychodynamic perspective of underlying motivations and emotions that affect information behaviour in general, and specifically information use. Drawing heavily from the field of psychoanalysis, the role of the unconscious presents an important consideration in information behaviour research. Psychodynamic perspectives of the unconscious are presented and discussed with regard to information behaviour.

There have been numerous theoretical perspectives in psychology (e.g., behavioural, cognitive, psychoanalytic, evolutionary, etc., which have contributed to a generalized disagreement in the field regarding the effectiveness of one approach versus another. In January 2010, the American Psychological Association issued a press release announcing the efficacy of psychodynamic therapeutic processes for bringing about long-term benefits, even after treatment ends (APA 2010). Despite the documented benefits brought about by psychodynamic processes, it has not been widely embraced either within the field of psychology or by other disciplines throughout much of the 20th century for a variety of reasons. Shedler explains that the attitude toward psychodynamic therapy results from several sources, including 'a lingering distaste in the mental health professions for past psychoanalytic arrogance and authority', comes from past decades when 'American psychoanalysis was dominated by a hierarchical medical establishment that denied training to non-MDs and adopted a dismissive stance toward research' (Shedler 2010: 98). This further resulted in the welcoming of non-psychodynamic approaches and overlooking psychodynamic perspectives and research.

In the early days of psychology in the 20th century, there was a reluctance to even talk about the idea of non-conscious mental processing. Behaviourism came about in the mid-1900s and focused on the observable and measurable aspects of behaviour, and excluded subjective experience and emotions when investigating stimuli that punish and reward behaviour. Ivan Pavlov's early experiments with dogs that were trained to salivate upon hearing a ringing bell are classic examples of behaviourism, also known as operant conditioning. Over time, however, the gaps left by excluding subjective considerations became obvious and later theorists began to modify this theoretical position. As Westen (2007: 78) notes, 'Subsequent theorists, however, began to populate Skinner's black box with feelings'.

It wasn't until the 1950s when psychology began rejecting behaviourism and began a systematic study of the mind. The rise of cognitive and social psychology gave way to more open discussions about previously rejected ideas regarding the unconscious. Wilson (2002: 4) reports, 'It became clear that people could not verbalize many of the cognitive processes that psychologists assumed were occurring inside their heads'. Social psychology was developing its own theories of how individuals develop stereotypes and judge other people's motivations and actions. It soon became clear, however, that the mental processes studied by cognitive and social psychologists were occurring outside the realm of consciousness and were becoming more evident in experimental psychology.

While the behavioural and cognitive perspectives waxed and waned, psychodynamic theory was emerging from psychoanalytic theory, having its origins in Freud's ideas about the unconscious motives that underlie our actions. Freud believed that the powerful influence of instinctive drives and the significance of developmental experience are what shape personality. While Freud has been the subject of much criticism, it has been over seventy years since his death, and psychoanalytic research has continued to progress. Despite the criticism, much of Freud's work has contributed to contemporary psychoanalytic theory (Westen 1999). Freud believed that much of our mental life (i.e., thoughts, feelings, motives) is unconscious and occurs outside our awareness. He also posited that mental processes, both affective and motivational, operate in parallel, which allows us to have conflicting feelings (Westen 2007; Shedler 2010). Freud also suggested that stable personality patterns begin in childhood and the mental representations we develop of our self and others, combined with the relationships we develop, guide our interactions. Finally, Freud believed that healthy personality development results in learning to regulate sexual and aggressive feelings, leading to maturation and independence.

Psychoanalytic theory focuses on the 'unconscious inner conflicts as people strive to achieve their goals' (O'Shaughnessy and O'Shaughnessy 2004: 166). It views behaviour as the outcome of motives, drives, needs, and conflicts. These unconscious processes influence the things to which we attend and how we feel (Pervin and John 2001). As a result, our unconscious thoughts and feelings direct much of our emotional life and guide our decisions. Decisions are not always the result of a purely rational cost-benefit analysis. Emotions are also stronger predictors of decisions than are cognitive attitudes, although attitudes have both an emotional and cognitive component (Westen 2007).

The cognitive perspective does not view unconscious thoughts and feelings as needing to be defended or influencing our behaviour. Instead, the cognitive perspective suggests that there is no difference between the conscious and unconscious; that unconscious thoughts and feelings are there because they never entered into consciousness or are simply automatic. While cognitive psychology still dominates the field, there is increasing recognition of its limited ability to explain the influence of unconscious processes. As a result, there is increasing interest in investigating the unconscious to understand the affect of the unconscious on human behaviour (i.e., wishes, desires, and motivation) (See, for example, Curtis 2009 and Westen 2007). LeDoux (1996: 267) succinctly states, 'much of what the brain does during an emotion occurs outside of conscious awareness'.

In sum, there is disagreement between the cognitive and psychoanalytic perspectives regarding the nature of the unconscious (Table 1). The psychoanalytic perspective stresses the irrational nature of the unconscious, particularly regarding sexual and aggressive feelings and motives. The cognitive perspective suggests that there is no fundamental difference between the conscious and unconscious; that unconscious thoughts and feelings are there because they never entered into consciousness or are simply automatic (e.g., driving a car). The cognitive perspective does not view unconscious thoughts and feelings as needing to be defended or influencing our behaviour.

| Psychoanalytic perspective | Cognitive perspective |

|---|---|

| Irrational, unconscious processes | Sees no fundamental difference between conscious and unconscious |

| Emphasis on motives and desires | Emphasis on thoughts |

| Focuses on motivational features of the unconscious | Focuses on non-motivating features of the unconscious |

The unconscious may play an important role in information behaviour, across the various components of information needs, information seeking, and, most importantly, in information use. Before investigating this question, it is useful to understand better the theoretical premises of the theory.

Building upon the historical origins, Shedler (2010) identifies seven features that distinguish psychodynamic therapy from other psychological perspectives. The first feature is that there is a focus on affect and the expression of emotion. In contrast, cognitive perspectives emphasize thoughts and beliefs. Although cognitive perspectives are beginning to acknowledge the role of emotion in human behaviour, it is constrained to an intellectual insight rather than one focused on emotional insight that resonates at a deeper level and can lead to behaviour change.

The second feature is that psychodynamic perspectives focus on an exploration of the individual's attempt to avoid distressing thoughts and feelings; avoidance of certain thoughts and feelings leads to a variety of actions, some of which are very subtle and difficult to recognize (e.g., a shift in topics during conversation when certain ideas arise). In psychodynamic theory, this avoidance is termed defense and resistance.

The third feature of psychodynamic therapy focuses on identifying recurring themes and patterns. Some individuals are aware of their recurring patterns that may not be constructive but may not feel that they are able to change them. Other individuals may not be aware of the patterns and are thus, unable to recognize or understand them.

The fourth feature of psychodynamic therapy is the recognition of how past experiences relate to present experiences. Psychodynamic therapy is often erroneously faulted for focusing on the past for its own sake, when in reality its focus is to understand how past experiences affect present psychological difficulties. People sometimes behave in the present on the basis of how they experienced a relationship in the past.

A fifth feature of psychodynamic theory is the focus on interpersonal relations. How people adapt to new situations is often based on past experiences with other relationships. People develop recurring patterns in relationships in childhood that allow them to adapt to their situations. This typically occurs with attachment relationships. These patterns then repeat themselves as they find themselves in situations where similar problems arise.

A sixth feature on psychodynamic therapy has to do with the therapeutic relationship. Although not directly pertinent to this discussion, there may be practical advances we can learn for information professionals from the interaction between people and their therapists. The relationship between the individual and the therapist is deeply important because it creates a situation where the emotionally charged themes of the individual's life can emerge, providing the opportunity to explore, understand, and rework them. Although information professionals rarely work this closely with a user, it is useful to be aware of possible reactions from users that give clues to the nature of the information needs of the individual. For example, the confidential nature of the information exchange between user and information professional may create situations where users reveal more than necessarily intended, whether through words, body language (e.g., avoiding eye contact), or actions (e.g., crying).

Finally, psychodynamic therapy encourages individuals to speak freely and without constraint in order to understand their self-perception and views of their relationships and experience. This process is often created over time and facilitation from the therapist before full disclosure and the ability to discuss private matters takes place. It is unlikely that this process will be emulated within the limited time frame of information professional and user, although it shares similar professional ethics with librarianship and information science in the area of user confidentiality.

Despite recent shifts in the field of psychology, information science has retained a particularly cognitive perspective when it comes to matters of the mind. Historically, the majority of the research literature of the field has been and continues to be cognitively based. With little exception, most of the research in the field presupposes an information processing model of mental life, with no mention of unconscious processes.

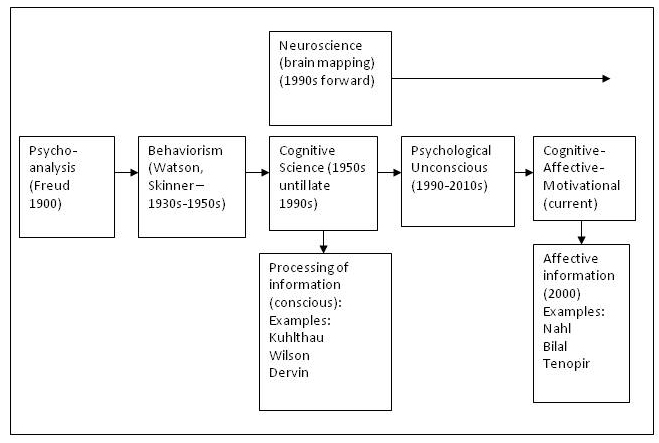

Information behaviour theories can be mapped onto psychological theories at a general level (Figure 1). The dates presented are not absolute and vary according to source. A brief history of psychology theories has been previously described above, but is repeated in graphic format to demonstrate the relationship and development of related theory in library and information science, which, by the problematic nature of information as a theoretical object, relies on a range of disciplines to help explain the interaction of human behaviour with information. In information science, the system-oriented, physical paradigm was predominant in the early days of the Cranfield experiments. It was not until the role of the user became of greater interest that the user-centred, cognitive paradigm arose (Raber 2003). The cognitive paradigm raised questions regarding the meaning of information, which was dependent upon the user's context; it was situationally-derived. Early studies in information behaviour focused on the mental processing of information as evidence in Figure 2 and exemplified by researchers including Kuhlthau, Dervin and Wilson, discussed in detail below.

Further research has continued to explore the user's perspective across within specific contexts, refining much of what has been based on Dervin's sense-making theory. Fisher et al. (2005) report seventy-two perspectives on information behaviour. Most of these theories are grounded in the cognitive perspective; most focus on the information processing of users in their sense-making tasks. Many of these theories examine the user's situation or context in which they are identifying a problem, seeking information, and then assimilating the information in order to make decisions. But as Westen (2007) suggested, decisions have both an emotional and cognitive component. In fact, he claims that emotions are stronger predictors of decisions than are cognitive attitudes and that in general, the greater the emotional importance, the more likely a decision will be based on emotion.

Despite the shift in psychology that was occurring in the period 1990 to 2010 to reconsider the existence and importance of the unconscious, information behaviour research continued to refine its understanding of the cognitive processes involved in the interaction between information and human behaviour. More recently there has been an interest in the role of affect and the role of emotion in information behaviour. While human emotions are likely grounded in developmental processes that occur during childhood, much of which dwell in the unconscious, information science research has not given full consideration of the role of the unconscious.

In sum, despite recent shifts in the field of psychology to include the unconscious, information science retains a particularly cognitive perspective when it comes to matters of the mind. Historically, the majority of the research literature of the field has been and continues to be cognitively based. With few exceptions, most of the research in the field presupposes an information processing model of mental life, with very little mention of unconscious processes.

Although the unconscious is rarely mentioned in information behaviour research, its presence have been observed and described in some studies. Specifically, several information seeking theories hint at some of the characteristics of the unconscious. Several studies report the observation of users becoming aware of an information need, or an information gap. For example, as early as 1960, Mackay reports that a user has 'a certain incompleteness in his picture of the world - an inadequacy in what we might call his "state of readiness" to interact purposefully with the world around him' (Mackay 1960: 11).

Taylor reports a similar observation. He describes the users' quest for information, saying, 'They develop their own search strategy, neither very sure of what it is they want nor fully cognizant of the alternatives open to them' (1968: 179), hinting at unconscious processes underlying their information needs. This becomes more fully developed in his model of question-negotiation, where he identifies four levels of question formation. The first, termed Q1, Taylor describes as 'the actual, but unexpressed need for information (the visceral need)' (1968: 182). This is where the individual recognizes:

the conscious or even unconscious need for information not existing in the remembered experience of the inquirer. It may be only a vague sort of dissatisfaction. It is probably inexpressible in linguistic terms. This need (it really is not a question yet) will change in form, quality, concreteness, and criteria as information is added, as it is influenced by analogy, or as its importance grows with the investigation (1968: 182).

Belkin also describes similar observations, stating that the anomalous states of knowledge representation of an information need:

arises from a recognized anomaly in the user's state of knowledge concerning some topic or situation and that, in general, the user is unable to specify precisely what is needed to resolve that anomaly. Thus, for the purposes of IR [information retrieval], it is more suitable to attempt to describe that ASK [anomalous state] than to ask the user to specify her/his need as a request to the system (1982: 62).

This suggests that the user may not always be able to describe the information need in the terms that will result in successful retrieval of information. Psychodynamic theory builds on this hypothesis by suggesting that the user may have underlying emotions and experiences that may (or may not) be in conflict, resulting in an inability to precisely articulate the information need. Cognitive theory stops short of this, because it 'suggests that interactions of humans with one another, with the physical world and with themselves are always mediated by their states of knowledge about themselves and about that with which or whom they interact' (1982: 65). The cognitive viewpoint does not adequately take into account the underlying thoughts and feelings to which the individuals themselves may not have access. This is an area where psychodynamic theory can contribute to our understanding of information behaviour. Belkin hints at this when he states:

The expression of an information need, on the other hand, is in general a statement of what the user does not know. Thus, the document is a representation of a coherent state of knowledge, while a query or other text related to an information need will be a representation of an anomalous, or somehow inadequate or incoherent state of knowledge (1982: 64).

Ingwersen reports similar concerns regarding users' inability to express their information needs. He states:

The point here has always been that the user is only capable of describing what he knows at a given point in time according to his current cognitive state, but not what he does not know yet and is actually searching for. Hence, the user may consequently only vaguely formulate a request for information by formulating fragments of his current cognitive state. However, what he might be able to do, in theory, is to state his underlying problem or motive (Ingwersen 1994: 104).

Kuhlthau's (1993) information seeking process model also hints at the unconscious thoughts and feelings that underlie information seeking behaviour. While she clearly acknowledges the affective experience of users' anxiety and uncertainty in information-seeking behaviour, she maintains a clearly cognitive approach to her study of users. Drawing upon the work of Dewey (reflective thinking), Kelly (personal construct theory), and Bruner ('constructivist view of the nature of human thinking and learning' (Kuhlthau 1993: 24)), she weaves together an important model of human information seeking. She recognizes the importance of experience and past behaviour, but does not consider the effects of the unconscious on information seeking behaviour.

Dervin comes closer to considering the thoughts and feelings that lie outside of our own awareness in her theory of sense-making. sense-making refers to an individual's awareness of their own situation and the ability to understand situations of high complexity or uncertainty in order to make decisions. Dervin proposes three information worlds in which Information1 is objective; describing reality of that which is external to the self. Information2 is more subjective and refers to ideas and is internal to the self, focusing on an individual's own reality. Information3 includes the process involved in making a decision and the process of becoming informed, i.e., the relationship between Information1and Information2 (Dervin 2003). While Information2 and Information3 may (or may not) include underlying thoughts and feelings, it is not explicitly stated or recognized that these may be of primary importance in our understanding of human behaviour in its interaction with information.

Returning to Taylor, his observations come close to recognizing users' unconscious influences when he identifies 'five filters through which a question passes' (Taylor 1968: 183). Included in this list are 2) objective and motivation and 3) the personal characteristics of inquirer. While not explicitly stated, Taylor suggests that the motivations and personal characteristics of the user may affect their ability to negotiate their information query with a librarian. Motivation, he continues, was identified by the librarians he interviewed, as 'critical to the success of any negotiation and consequent search', as it 'qualifies the subject, or may even alter the entire inquiry' (Taylor 1968: 185). One librarian concluded: 'We can't help him unless we understand his needs as well as he does' (Taylor 1968: 185). Therein lies the rub: psychodynamic theory suggests that underlying thoughts and feelings may exist outside of our awareness. If a user cannot identify their own needs, how can an information professional or system design help satisfy those needs?

Harmon and Ballesteros raised similar questions regarding the effectiveness of information queries if we are unable to fully elicit accuracy in the user's need. Their hypothesis was that 'unconscious cognition plays a key role in the framing of inquiry, (and for that matter, of discovery in the communication chain), and it persists throughout the entire inquiry cycle, whether it be formal reasoning of casual day-to-day problem solving' (Harmon and Ballesteros 1997: 423). They provide additional historical evidence of concerns about the hidden meaning embedded within user queries. They quote Wyer (1930): 'The art of mind-reading, then is to know how to give people what they do not know they want' (Harmon and Ballesteros 1997: 101). The also suggest that:

If only consciously expressed needs for information are dealt with, the underlying information need or problem may either be ignored or only partially solved. Further, attempts to address only those queries that are expressed in a conscious mode may treat the symptoms of the problem rather than the true problem itself. Such attempts can even give the illusion of problem resolution, and can hence be misleading, counter-productive, or even dangerous (Harmon and Ballesteros 1997: 424).

The points presented by Harmon and Ballesteros underscore the main points in this paper. They differ, however, in their view of the nature of the unconscious. They also consider the role of the unconscious but from a cognitive perspective, focusing on how the 'unconscious mental processes can potentially affect the course of inquiry' (Harmon and Ballesteros 1997: 424), rather than focusing on how the underlying motivations, emotions, desires, thoughts, and wishes can affect all interactions involving information and human behaviour. The emphasis suggested here presents a more holistic picture of an individual, not just their cognitive processes and not just those at the conscious level.

Cole also recognizes a similar observation when comparing similar awareness of information gaps between theories posited by Belkin (problem situation), Dervin (situation gap), and Kuhlthau. He states, 'In the three theories, the "situation" leads to a cognitive "gap"' (1997: 58) While the awareness of the gap may occur at a cognitive level, its underlying cause cannot be assumed to originate there.

To fully understand what effects the unconscious has upon the ways in which users interact with information, research in the field can draw upon many disciplines. Brain research of the past fifteen to twenty years is revealing how people think, including the relationship between the conscious and unconscious mind (see, for example, Damasio 2003). This research can point us to a new understanding of how people's use of information is influenced by the complex relationship between conscious, unconscious, body, and society. By focusing on the limited assumptions of a cognitive paradigm, information behaviour research prevents itself from advancing our knowledge of the true understanding of our users. Drawing from research in the business literature on consumer behaviour, Zaltman (2003) identifies six fallacies of assumptions that are useful to identify the limitations of the cognitive perspective of information behaviour. The fallacies are listed below:

As a result of these fallacies, the cognitive perspective is limited in several ways. First, the limitations presented by the cognitive perspective may lead researchers to draw conclusions based upon incomplete findings. The inclusion of a psychodynamic perspective provides additional opportunities for developing real insight into the interaction of information and human behaviour. A second limitation is that of emphasizing the wrong aspects of human behaviour. There are estimates that up to 85-95% of thought takes place in the unconscious outside of our awareness (Zaltman 2003; Westen 2007; Lindstrom 2010). If that is the case, information behaviour research may be investigating the other 5%.

While cognitive processes (i.e., the ways in which we think about things) are vital to our understanding of the user's mental processes, they only provide us with a partial understanding of the ways in which people interact with information. With the recent addition of including affect in our understanding of the interaction between human behaviour and information, it would be useful to consider the full realm of emotion, not just those at the conscious level. While information behaviour theories have recently recognized the importance of affect in the interaction between user and information, and the fact that information behaviour is not necessarily rational, they have not considered the role of the unconscious in that interaction.

The of the features of psychodynamic theory can provide information science with ways to investigate the unconscious in information behaviour research. For example, psychodynamic theory focuses on affect and the expression of emotion. Information behaviour research is already pushing the boundaries of cognitive explanations by questioning the role of emotions (see, for example, Julien et al. 2005; Giarlo 2006; Nahl and Bilal 2007). The title of Fulton's (2009) paper, The pleasure princple: the power of positive affect in information seeking, utilizes a phrase coined by Freud, although no mention is made of its origin or its meaning as referring to the motivation of Freud's id to seek pleasure.

Psychodynamic theory also suggests that people avoid thoughts and feelings which are distressing and may develop defense mechanisms. The defense mechanisms can manifest themselves in a number of ways which have implications for information work. For example, users may avoid the discussion of certain topics which may have particular meaning to them, of which neither the user nor an information practitioner may have knowledge. This shift could provide clues to the information practitioner regarding selection of materials or specific ways of eliciting information from the user during a reference interview. Further, since language is considered to be a metaphorical representation of a user's unconscious, it is possible to understand how those feelings, thoughts, and behaviours are organized, allowing us to evaluate and apply information to a user's needs. For example, priming experiments from psychology may provide areas for fertile research in libray and information science, investigating ways in which we can prime our users to better articulate their information needs or identify barriers to information use.

Psychodynamic theory also focuses on interpersonal relations. It supports the contention that information can be used to facilitate and enhance a user's experience and richness of life (e.g., bibliotherapy, information therapy). Targeting tailored information to specific users at critical times (e.g., health crises) can help users make specific decisions or change their behaviour. Trust is an important component of both psychodynamic theory and information practice as it provides reassurance of confidentiality and non-judgment.

Westen (1998) reports that the history of psychoanalytic perspectives which began with Freud, have slowly become adopted by and integrated into cognitive perspectives from the behavioural side of the house. If information behaviour research is experiencing a shift from a person-centred approach to a person-in-context (or situational) approach as Vakkari (2008) notes, it seems reasonable to take notice of changes in psychological theories and consider their application for our own research. In other words, we should be pursuing a similar agenda, most notably by compounding our knowledge regarding affect and motivation into contemporary information behaviour models. It raises the question, should there be a shift from considering information behaviour as linear and conscious to behaviour that operates at many levels, including an unconscious level that particularly concerns motivation and emotion?

The primary criticism that appears to be aimed at psychodynamic theories in psychology is that it is not measurable, although this is a point of disagreement among psychological researchers. Like information science, psychology faces similar arguments over how to approach the study of the human mind. The cognitive approach takes more of a black box approach, seeing the mind as an information processing unit that can be quantitatively measured. The psychodynamic approach promotes alternative approaches that are more qualitatively based (e.g., projective tests such as the thematic apperception test and Rorschach ink blot tests). The problems that arise from these perspectives are not unlike our own disagreements over approaches associated with the physical and cognitive paradigms.

The field of psychology has struggled with these issues far longer than information science and has much to contribute to our understanding of the role of the unconscious in human behaviour. In our case, we are interested in how the underlying thoughts and feelings affect the interaction between information and human behaviour. This is not meant to imply that previous research from a cognitive perspective is not valuable; rather, the purpose of this paper is to bring attention to what appears to be an important oversight in our investigation of the interaction between information and human behaviour. The addition of this theoretical perspective will provide substantial clues that can contribute to many aspects of information science; everything from the reference interview to system design. Psychotherapy relies upon the words exchanged between two people to effect changes in behaviour. The underlying psychodynamic theories offer fertile ground for understanding the interaction between information and human behaviour. If library and information science is to advance its understanding of information behaviour, it needs to move beyond merely applying existing theory and method to include other theories and methodological tools available to us; in this case, particularly from the field of psychology, whose aim it is to investigate human behaviour and behaviour change. The use of projective tests in psychology, although controversial, are becoming more widely accepted in psychological research as they have improved in their validity and reliability scores (L. Handler, personal communication, June 10, 2010). These tests allow participants to assign their own interpretation of a particular stimuli, usually an image, revealing their unconscious emotions in the process. Common projective tests include the Rorschach inkblot test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), free association, and sentence completion. These tests allow individuals to reveal their underlying motivations, defenses, and conflicts when they may not themselves be aware of them. These tests can be used in conjunction with the presentation of information materials and experiences, the results of which can be used to enhance the delivery of information services and products. As Heinstrom (2003) aptly suggests, 'search systems and information services must be further developed to better account for individual differences'. While Heinstrom was investigating personality types, the relationship between unconscious processes and personality types is closely tied and contextually dependent. Both present considerations for future research in our understanding of the relationship between information and human behaviour.

Kendra Albright is Associate Professor in the School of Library and Information Science, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina. She received her Ph.D.degree in Communications and Master of Library and Information Science from the University of Tennessee. She can be contacted at albright@sc.edu.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the author, 2011. Last updated: 31 December, 2010 |