vol. 16 no. 1, March, 2011

vol. 16 no. 1, March, 2011 | ||||

The term community of practice was originally introduced by Lave and Wenger (1991) and further developed by Wenger (1998) and has been described as 'one of the most influential concepts to have emerged within the social sciences during recent years' (Hughes et al. 2007: 1). However, as it approaches the two-decade milestone, it faces a midlife crisis in the form of mounting conceptual critiques and a recent downturn in hitherto robust publication trends. As shown in Figure 1, a search for 'community of practice' OR 'communities of practice' in the EBSCO Business Source Complete database revealed, from 2005 onwards, a decrease in publications in the practitioner literature (which in EBSCO includes magazines, newspapers and trade publications, but also book reviews published in academic journals), followed by a more recent decline in academic journals, although it is too early to know if it constitutes a trend (the search printout is available from the author).

Communities of practice have been described as 'groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis' (Wenger et al. 2002: 4). Examples might include a group of nurses who discuss patient cases over their daily lunch meeting (Wenger 1996), petrophysicists involved in deep-sea petroleum exploration at Shell who meet weekly to explore issues and real problems they face in their formal teams (McDermott and Kendrick 2000), Chief Information Officers from various companies in the San Francisco area who meet monthly for a technical presentation and discussion followed by dinner (Moran and Weimer 2004); or public defence attorneys sharing a county office who learn from each other how to improve their court performance and thereby develop their professional identities (Hara and Schwen 2006).

The concept has led to far-reaching insights about workplace learning. Researchers found that employees are constantly learning as they go about their daily work and much of this learning bears little relation to, and is often at odds with, formal training and canonical work procedures (Brown and Duguid 1991; Wenger 1998). Rather, learning is a matter of becoming competent practitioners of informal communities, which, through the shared practices of their members, provide a living repository for knowledge (Orr 1990; Brown and Gray 1995). Thus communities of practice are not confined to formal apprenticeships, but are natural social structures existing wherever people work and accomplish things together (Wenger 1998).

Theorists now see communities of practice as an essential component of the knowledge-based view of the firm (Kogut and Zander 1996; Brown and Duguid 1998; Cook and Brown 1999; Tsoukas and Vladimirou 2001; Grover and Davenport 2001). For their part, managers increasingly view communities of practice as privileged sites of knowledge-sharing and innovation (Prokesch 1997; Swan et al. 1999; Lesser and Everest 2001). Moreover, after disappointing results from first-generation knowledge management projects, with their heavy emphasis on technological solutions for knowledge-sharing (Scarbrough 2003; Thompson and Walsham 2004; McDermott 1999), communities of practice have been recognised as an indispensible element of organizational knowledge management programmes. In a field that is criticised for its increasing fragmentation (Alvesson and Kärreman 2001; Wilson 2002; Gray and Meister 2003), communities of practice have emerged as one of the few common denominators in existing typologies of knowledge management (Hansen et al. 1999; Despres and Chauvel 2000; Binney 2001; Earl 2001; Alvesson and Kärreman 2001; Kakabadse et al. 2003; Lloria 2008).

Even as the concept reaches the two decade milestone, it still lacks a widely accepted definition. The literature displays considerable confusion, failing to distinguish communities of practice from other social structures concerned with knowledge and learning, such as occupational communities, organizational subcultures, networks of practice and epistemic cultures. Moreover, both academics and practitioners have interpreted and adapted the concept in many different ways, for which the ambiguity of the seminal studies is mostly responsible.

Widespread diffusion, non-agreement on a definition and diversity of adaptations are all symptoms identified by Benders and van Veen (2001) in their conceptualization of a management fashion, which they define as 'the patterns of production and consumption of temporarily intensive management discourse and the organizational changes induced by and associated with this discourse' (2001: 40).

These authors critique Abrahamson's (1996) seminal conceptualization of a fashion for failing to include what they consider a key characteristic, namely, interpretative viability. This refers to a certain degree of ambiguity in a concept, which endows it with greater appeal to a broader set of potential users. A concept that is loosely specified leaves room for a manager to see it as the solution for a vexing problem, or to selectively adopt from the concept those elements which s/he finds most appealing. Such concepts can be operationalized in a number of different ways, can be deployed to achieve different purposes and can simultaneously appeal to different constituencies since each can interpret the concept in their own way.

Benders and van Veen (2001) also view Abrahamson's conceptualization as simplistic in classifying fashion users as either setters (academics and consultants) or followers (docile managers). Instead they argue that, to a certain extent, all actors develop their own interpretation of the concept, adapt it to create fashionable discourse and use this to promote organizational change.

This review found that Benders and van Veen's model provides a plausible explanation for the rapid diffusion of the community of practice concept and the proliferation of diverging interpretations, which has led to the current crisis. In the historical evolution of the literature, three events are singled out as deserving special attention:

Since Benders and van Veen's fashion model addresses management discourses and their effects on organizations, this review will limit its purview to business and organizational studies. Nevertheless, the concept has also been very influential in the fields of education, sociology and anthropology. For extensive reviews of those literatures, the reader is referred to Davenport and Hall (2002) and Koliba and Gajda (2009).

Beyond this introduction, the review is organized into seven sections. The first presents early studies and the evolution of the concept through the seminal works of Lave, Wenger, Orr, and Brown and Duguid. Section two describes Wenger's (1998) theoretical framework of communities of practice, starting with his broader social theory of learning, where communities of practice are an embedded element, followed by a focus on communities of practice and their defining dimensions. The third section reviews related social groups and their differences with respect to communities of practice. Section four examines alternative or competing designations that have been proposed for communities of practice. Section five discusses direct challenges and critiques to Wenger's 1998 framework. The major part of the review is contained in section six, which examines theoretically grounded contributions to CoP research published in the last decade. The final section presents detected trends and conclusions.

The concept of community of practice was originally proposed by Lave and Wenger (Lave and Wenger 1991). The focus of their research was social learning as a critique of the then dominant cognitive approach. They grounded their theory on five ethnographic studies of traditional apprenticeship institutions: Yucatec midwives in Mexico, Vai and Gola tailors in Liberia, U.S. Navy quartermasters, U.S. supermarket meat cutters and U.S. nondrinking alcoholics. They proposed a theory of learning whereby people learn by becoming acknowledged, but peripheral, members of social communities where knowledge resides, not as abstract ideas, but as embodied and shared practices. They view learning as the process of joining a community and actually taking part in its practices, beginning with the most basic and gradually mastering the most complex, while working alongside established members. In this way, newcomers gradually change their identity to that of an insider. They named this progression from peripheral membership to full insider status legitimate peripheral participation and it is their main intended contribution and the title of their book. They coined the term communities of practice, without giving a formal definition, to designate the communities that apprentices joined. Thus, by design, their monograph focuses on the apprentices and the process of legitimate peripheral participation, while paying less attention to the community itself.

The communities of practice described by Lave and Wenger were characterized by legitimate peripheral participation, learning (equated to the construction of a practitioner identity) and a practice. Though sketchy, this model is still currently in use, especially in studies focusing on the inbound trajectories of newcomers into established communities of practice (e.g., Harris et al. 2004; Handley et al. 2007; Campbell 2009).

Another seminal study is Orr's (1990) ethnography of Xerox photocopier field technicians, which famously revealed the extent to which conventional job descriptions failed to capture the intricacies of practice. The company assumed the tech. reps. had an individual job which could be accomplished by simply following the repair procedures specified in the official service manual. In practice, though, Orr discovered the representatives had developed a strong informal community that met daily for breakfast to exchange problem-solving tips. Specifically, they crafted and told each other stories about the machines they fixed. This narration served the dual purpose of holding contextualized actionable knowledge about individual machines and enacting their professional identities as (heroic) representatives. Because they already shared a great deal of common ground (Bechky 2003), this narration was an effective way of communicating complex tacit knowledge about the machines. In fact, becoming a member of the community was as much about learning to tell good stories as it was about learning mechanical repair skills.

At the time he wrote his ethnography, Orr was not unaware of the community of practice concept (Duguid 2006); nevertheless, he used van Maanen and Barley's (1984) construct of occupational community to describe the community of technicians and reaffirmed this choice in his later book (Orr 1996). Contu and Willmott (2003: 289) further note Orr's debt is 'principally to the work of Suchman rather than Lave and Wenger'. Other researchers nevertheless acknowledge Orr's ground-breaking study as the earliest ethnography of a community of practice (Raelin 1997; Brown and Duguid 2001; Teigland 2003).

The third seminal study by Brown and Duguid (1991) articulated the relevance for business organizations of what initially appeared like an esoteric concept developed by anthropologists. These authors were first to argue that, despite their near-invisibility, communities of practice were the key to effective workplace learning and innovation and therefore constituted an important concern for managers, especially in knowledge-based organizations.

They base their theorizing on Orr's (1990) account and were thus the first to propose a reinterpretation of Orr's thick description in terms of the positive contribution communities of practice make to the organization. Others would later propose more conflictual reinterpretations (Fox 2000; Contu and Willmott 2003; Cox 2005; Contu and Willmott 2006). Specifically, Brown and Duguid (1991) propose three overlapping categories as an explanatory model that fits the representatives' practice: narration, collaboration and social construction. This first model goes well beyond Lave and Wenger's intuitive notion and probably explains why their article is cited by many as the seminal reference.

Narration is the crafting and exchanging of war stories about the repair of specific machines. Telling a story about a faulty machine was the representatives' heuristic for building a causal map that gave a coherent account of the problem. Because the story included and took into account the social and material context in which the machine operated, it provided a much more actionable account than the decision tree prescribed by the official service manual.

Collaboration refers to the fact that the reps spontaneously organized themselves as an informal team in order to collaborate with each other, trading stories and helping each other to make sense of the idiosyncrasies of different machines. This occurred despite the fact that the corporation viewed the job as individual and asocial.

Finally, the category of social construction manifests itself in two dimensions. First, that the reps build through their interactions a shared understanding, in effect a representatives's model of the machines. Second, that by becoming proficient in the telling of stories, the representative simultaneously builds his own identity and contributes to the collectively-held knowledge base of the community of practice.

Brown and Duguid next adapt Lave and Wenger's (1991) concept to characterize the representatives' actions as learning to function, or developing insider identities, in an organizational community of practice. 'Workplace learning is best understood, then, in terms of communities being formed or joined and personal identities being changed' (1991: 48). This organizational community is slightly different from the communities described by Lave and Wenger and not just by the fact that it is embedded in a large corporation, whereas the former communities were largely autonomous. Brown and Duguid also prefer the egalitarian community described by Orr (1990: 33), 'the only real status is that of member'; whereas Lave and Wenger's community of practice displays wide status differentials between masters and apprentices.

A final adaptation is their call for organizations to reconceive themselves as communities of communities of practice and thereby release the innovative potential of these continuously learning groups. They develop a vision (further developed in Brown and Duguid 1998) of multiple communities of practice acting in a loosely coordinated fashion, whereas Lave and Wenger's communities were isolated and self-sufficient.

Thus, in developing their conceptualization of an organizational community of practice, Brown and Duguid have used the concept's interpretative viability to perform the necessary adaptations to transplant it into organizations and thereby present the business community with a novel organizational group that held the key to continuous learning, knowledge sharing and innovation. Over the following years, various articles and interviews, mostly by Brown, marketed the concept to various audiences (Brown and Grey 1995; LaPlante 1996; Brown and Duguid 1996; Stucky and Brown 1996; Brown 1998; Brown and Duguid 2000a) and fairly soon the business media picked up on the trend.

A final point worth stressing is that at no point in Brown and Duguid's article are communities of practice defined, just as they were not in Lave and Wenger (1991), nor, of course, in Orr's (1990) ethnography. The conclusion from this historical overview, using Benders and van Veen's terminology, is that the seminal studies introduced an appealing concept with substantial interpretative viability. In subsequent years, the resulting ambiguity allowed the concept to be used and interpreted in increasingly divergent ways.

The mid- and late-nineties can be characterized as a period of increasing excitement about communities of practice, with enthusiastic accounts appearing in business magazines (e.g., Brown and Gray 1995; Manville and Foote 1996; Roth 1996; Stucky and Brown 1996; Stewart 1996; Prokesch 1997; Stamps 1997; Graham et al. 1998; Wright 1999; Stewart 2000, Ward 2000; Brown and Duguid 2000a). This growing interest was partly due to the fact that the concept gives a name to the familiar human need to belong and take part in a group of like-minded peers. Indeed, Wenger (1999) argues communities of practice are natural social structures, citing prehistoric tribes and medieval guilds as historical examples. Furthermore, the same years witnessed an explosion of interest in knowledge management. Ponzi and Koenig (2002) report that publications on the subject had very rapid growth after 1996 and hit a peak of almost 600 articles in 1999. Clearly, some of these studies were written using the new perspective afforded by communities of practice.

In 1998, Wenger published his now famous ethnography of insurance claims processors (Wenger 1998). After his research with Lave, Wenger shifted his attention from the process of induction of new members to the community of practice itself. He based his new theorizing on ethnographic fieldwork conducted in 1989-1990 in a medical claims processing centre operated by a large US insurance company. The result is a novel framework that constitutes a very substantial development of Lave and Wenger's intuitive notion. The book remains, to this day, the most detailed and comprehensive treatise on communities of practice (Schwen and Hara 2003; Plaskoff 2003; Meeuwesen and Berends 2007; Zhang and Watts 2008), arguably making Wenger's theory the de facto benchmark (Lindkvist 2005; Iverson and McPhee 2008). This is also suggested by its becoming the target of a growing number of critiques (e.g., Fox 2000; Contu and Willmot 2003; Marshall and Rollinson 2004; Cox 2005; Roberts 2006).

However, as already mentioned, the book fails to provide an explicit definition of community of practice and the proposed framework is fairly complex and difficult to operationalize. Hence, subsequently, very few studies applied this more developed model (e.g., Smeds and Alvesalo 2003), choosing instead to interpret and adapt Lave and Wenger's (1991) intuitive notion or, to a lesser extent, Brown and Duguid's (1991) model (e.g., Lee and Cole 2003; Pan and Leidner 2003; Holmqvist 2003). In-depth engagement with Wenger's framework did not come until later (e.g., Thompson 2005; Goodwin et al. 2005).

By the time Wenger's ethnography appeared, a trend was already visible in the literature which would continue after the turn of the century. Studies were roughly aligned along two distinct camps which might be labelled the organizational studies interpretation and the knowledge management interpretation. The first group emphasizes theory development by describing emergent, informal organizational communities of practice. The second group emphasizes the business value of communities of practice and aims to identify, support and/or launch strategic communities of practice in order to manage organizational knowledge. The two perspectives are displayed in Table 1 which highlights their contrasting interpretations of various characteristics and capabilities as reflected in representative studies. Thus, as the concept approached its tenth birthday, signs of a management fashion were in evidence, with rising publication trends and interpretative viability leading to increasingly divergent interpretations.

Wenger's (1998) book is arguably the key reference in the organizational studies perspective, although in later publications he would move toward the knowledge management view. However, Wenger argues that he uses the concept mainly as an entry point into a broader social theory of learning, or as a way to bring together social theory and learning theory (Wenger 1998: 5). The concept of is tightly embedded within this framework which is described in some detail in the following section.

| Organizational studies interpretation | Knowledge management interpretation |

|---|---|

| These studies interpret communities of practice as emergent, informal, self-organizing groups who set their own learning agenda and operate beyond management control. Therefore, the positions they emphasize are: | These studies interpret communities of practice as hidden resources that should be identified, supported by management and charged with pursuing knowledge initiatives that have strategic value for the organization. Therefore, the positions they emphasize are: |

| 'Communities of practice are informal emergent structures' Orr (1990); Brown and Duguid (1991); Hendry (1996); Wenger (1998); Gherardi and Nicolini (2000) |

'Communities of practice are organizational knowledge assets' Prokesch (1997); Wenger and Snyder (2000); Lesser and Everest (2001); Lesser and Storck (2001); Kimble and Bourdon (2008) |

| 'Because communities of practice are informal, they are not under management's control' Brown and Duguid (1991); Wenger (1998); Gongla and Rizzuto (2004); Thompson (2005); Duguid (2006); Pastoors (2007); Raz (2007) |

'Because communities of practice are knowledge assets, they should be managed' Prokesch (1997); Hanley (1998); Lesser and Everest (2001); Cross et al. (2006); Probst and Borzillo (2008) |

| 'All competencies of the organization reside in communities of practice' Brown and Duguid (1991); Wenger (1998); Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001) |

'Core competencies of the organization reside in communities of practice' Brown and Gray (1995); Manville and Foote (1996); Roth (1996); Wenger (1999); McDermott and Kendrick (2000); Barrow (2001); Saint-Onge and Wallace (2003) |

| 'Communities of practice emerge to solve routine problems' Orr (1990); Wenger (1998); Gherardi and Nicolini (2000); Tsoukas and Vladimirou (2001); Hara and Schwen (2006) | 'Communities of practice should focus on strategically important problems' Brown and Gray (1995); Wenger (1999; 2004); McDermott and Kendrick (2000); Barrow (2001); Saint-Onge and Wallace (2003); Anand et al. (2007) |

| 'The knowledge of the community of practice is situated and held communally, hence it cannot be extracted' McDermott (1999); Newell et al. (2002); Duguid (2006); Cox (2007b) |

'Knowledge management systems should build on and leverage the natural knowledge-sharing practices of a community of practice Brown (1998), Wright (1999), Brown and Duguid (2000a); Bobrow and Whalen (2002) |

| 'Communities of practice emerge of their own accord' Orr (1990); Wenger (1998); Gherardi and Nicolini (2000; 2002); Hara and Schwen (2006) | 'Communities of practice can be designed and launched' McDermott and Kendrick (2000); Barrow (2001); Wenger et al. (2002); Plaskoff (2003); Saint-Onge and Wallace (2003); Thompson (2005); Anand et al. (2007); McDermott (2000; 2007); Meeuwesen and Berends (2007) |

| 'Communities of practice subvert management authority' Orr (1990); Korczynski (2003); Cox (2005); Duguid (2006); Raz (2007) | 'Communities of practice are the heroes of the organization' Brown and Grey (1995); Prokesch (1997); Brown (1998); Stewart (2000); Brown and Duguid (2000a); Barrow (2001) |

| Communities of practice are (just) an analytical category' Contu and Willmott (2003; 2006); Gherardi (2006) |

'Communities of practice are a new organizational group, the key to managing knowledge and innovation' Brown and Duguid (1991; 2000a); Brown and Grey (1995); Wenger and Snyder (2000); Kimble and Bourdon (2008) |

| 'Communities of practice benefit mostly their own members' Orr (1990); Ibarra (2003); Moran and Weimer (2004) | 'Organizations can harvest the knowledge of communities of practice' Manville and Foote (1996); Prokesch (1997); McDermott and Kendrick (2000); Bobrow and Whalen (2002); Probst and Borzillo (2008); Kimble and Bourdon (2008) |

Wenger (1998) breaks with cognitive learning theories by proposing to focus on meaningfulness, which he views as the ultimate aim of learning. This focus, together with the premise that meanings are negotiated in social communities, implies that the social nature of human beings is an essential enabler of learning. This is not to deny the possibility or the value of individual learning, but to make the important assertion that meanings cannot be determined in isolation.

Wenger defines the negotiation of meaning as 'the process by which we experience the world and our engagement in it as meaningful' (1998: 53). This process is embedded in the practices of communities of practice. Moreover, it is constituted by the interaction of two further processes termed participation and reification. Participation is 'the process of being active participants in the practices of social communities and constructing identities in relation to these communities' (1998: 4, emphasis in the original). Reification is 'the process of giving form to our experience by producing objects that congeal this experience into "thingness" [in order to] create points of focus around which the negotiation of meaning becomes organized' (1998: 58).

Human learning is chiefly about the negotiation of new meanings rather than the acquisition of new skills or information (Wenger 2005). The negotiation of meaning takes place in communities of practice, social groups that organize themselves to pursue enterprises deemed valuable to their members. In so doing, these communities define what it means to be a competent practitioner with respect to their enterprise, be it fixing photocopiers (Orr 1990), building flutes (Cook and Yanow 1993), or processing insurance claims (Wenger 1998). 'Learning is therefore a social becoming, the ongoing negotiation of an identity that we develop in the context of participation (and non-participation) in communities and their practices' (Wenger 2005: 15).

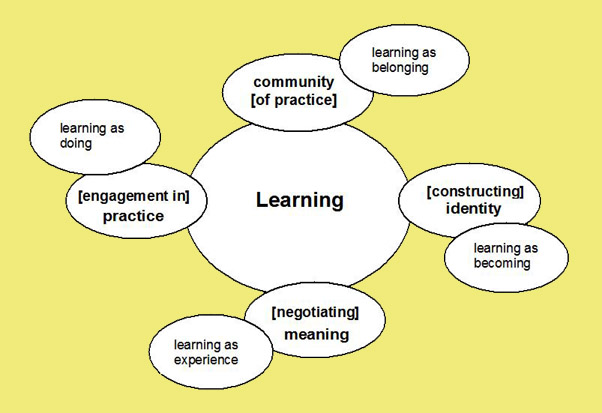

Thus, although the communities of practice concept has taken centre stage, it plays a subordinate, instrumental role in Wenger's social theory of learning. It enables the theory to focus on meaningfulness by locating learning within a social structure where its meaning can be collectively negotiated. Specifically, the framework brings together four interconnected and mutually defining elements:

(Wenger 1998: 5)

- Meaning: a way of talking about our (changing) ability -individually and collectively - to experience our life and the world as meaningful.

- Practice: a way of talking about the shared historical and social resources, frameworks and perspectives that can sustain mutual engagement in action.

- Community [of practice]: a way of talking about the social configurations in which our enterprises are defined as worth pursuing and our participation is recognizable as competence.

- Identity: a way of talking about how learning changes who we are and creates personal histories of becoming in the context of our communities.

To illustrate the connections between learning and these four elements and to highlight the distinct processes that result in learning, Wenger (1998: 5) proposed a diagram, which is reproduced with slight changes in Figure 2.

The diagram makes clear that the community of practice is just one element (and not even the core) of Wenger's learning theory, albeit an indispensible one because it analytically ties together all the elements into a coherent framework. As mentioned before, it is the concept that has taken centre stage, probably because it evokes the familiar human experience of participating in a group of like-minded peers, as hinted in the paragraph where Wenger (1998: 45) formally introduces the concept:

'Being alive as human beings means that we are constantly engaged in the pursuit of enterprises of all kinds, from ensuring our physical survival to seeking the most lofty pleasures. As we define these enterprises and engage in their pursuit together, we interact with each other and with the world and we tune our relations with each other and with the world accordingly. In other words, we learn. Over time, this collective learning results in practices that reflect both the pursuit of our enterprises and the attendant social relations. These practices are thus the property of a kind of community created over time by the pursuit of a shared enterprise. It makes sense, therefore, to call these kinds of communities communities of practice' (Wenger 1998: 45).

Within this lengthy description, which is not strictly a definition, the three elements of engagement, enterprise and practices deserve a particular emphasis because Wenger uses them to join the concepts of community and practice into a unitary construct. He does this by describing three dimensions of practice as the source of coherence of a community (of practice), i.e., as what makes that particular kind of community cohere. He thus describes them as constitutive or defining dimensions of communities of practice (Wenger 1998):

The presence of these three dimensions in a group is a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a community of practice and they also provide a more straightforward way of operationalizing Wenger's model than the earlier description. Also helpful is a list that Wenger provides of empirical indicators of the existence of a community of practice. These indicators, whose ethnographic origin is readily apparent, can be classified as specific manifestations of the defining dimensions, as shown in Table 2.

| Dimension | Indicators of a community of practice |

|---|---|

| Mutual engagement | 1) Sustained mutual relationships - harmonious or conflictual. 2) Shared ways of engaging in doing things together. 3) The rapid flow of information and propagation of innovation. 4) Absence of introductory preambles, as if conversations and interactions were merely the continuation of an ongoing process. 5) Very quick setup of a problem to be discussed. |

| Joint enterprise | 6) Substantial overlap in participants' descriptions of who belongs. 7) Knowing what others know, what they can do and how they can contribute to an enterprise. 8) Mutually defining identities. 9) The ability to assess the appropriateness of actions and products. |

| Shared repertoire | 10) Specific tools, representations and other artefacts. 11) Local lore, shared stories, inside jokes, knowing laughter. 12) Jargon and shortcuts to communication as well as the ease of producing new ones. 13) Certain styles recognised as displaying membership. 14) A shared discourse reflecting a certain perspective on the world. |

It should be noted that the operationalization of Wenger's model requires just the three defining dimensions mentioned above and not the more fundamental processes of negotiation of meaning, participation and reification. These concepts, although central to Wenger's social theory of learning, are not especially helpful in defining communities of practice or to describe their empirical attributes.

Wenger defines participation as the social experience of living in the world in terms of membership in social communities and active involvement in social enterprises. Moreover, he explicitly qualifies participation as broader than mutual engagement (1998: 55). Hence, not all participation involves communities of practice; it may involve various types of social structures and do so without engagement in practice.

Similarly, Wenger (1998: 58) defines reification as the process of giving form to our experience by producing objects that congeal this experience into 'thingness' in order to create points of focus around which the negotiation of meaning becomes organized. So defined, the process of reification becomes a basic building block of practically any human discussion and certainly not limited to interactions taking place within an established community of practice. Even something as transient as a conversation on an aeroplane would very likely make use of reification. Reification is a constitutive process in the development and use of a shared repertoire, but again, it is broader and more basic than this Wenger concept

In sum, communities of practice display processes of participation and reification, but so do other types of groups and social structures, which is why these processes are not useful for the purpose of empirically identifying communities of practice.

Wenger's (1998) framework is a very substantial theoretical development of Lave and Wenger's (1991) 'intuitive notion', grounded on an organizational ethnography of a single community of practice. Even though a closed definition of community of practice is not proposed, the detailed framework could have set bounds to the interpretative viability of the concept if it had been promptly adopted in relevant studies. Still, it is not an easy model to operationalize, which probably explains the paucity of studies that use this model instead of the more adaptable notion of Lave and Wenger (1991) or Brown and Duguid (1991).

In a later theoretical essay, Wenger (2000b) argues that organizations should design themselves as social learning systems, constituted by communities of practice, boundary processes between them and the identities participants develop as they participate in these systems. The paper constitutes a fairly compact summary of the 1998 book, but again fails to provide an explicit definition of community of practice.

Other writings by Wenger are aimed at practitioners (1999; 2000a; 2004). Most particularly, his book co-authored with McDermott and Snyder (Wenger et al. 2002) is a practical guide for organizations wishing to launch and nurture communities of practice. Several authors have critiqued Wenger for this popularization of a highly complex concept and for his shift from what is interpreted as an emancipatory discourse in Lave and Wenger (1991), to a managerialist discourse in his practitioner writings (Fox 2000; Contu and Willmott 2003; Cox 2005; Hughes 2007).

This review considers Wenger's (1998) framework as a critical and lasting contribution to the literature and can only deplore the lack of subsequent empirical studies by the author, which surely would have contributed to a more focused and nuanced understanding of this complex notion. As things turned out, the reviewer feels compelled to trace some of the conceptual confusions in the literature to the introduction of a simplified model by Wenger et al. (2002), now consisting of Community, Domain and Practice, as well as some liberties taken with respect to the 1998 framework, such as the possibility of 'distributed communities of practice' counting thousands of members (in effect abandoning the 1998 criterion of direct mutual engagement). This relaxation of the carefully balanced 1998 framework reinforced interpretative viability, contributed to the proliferation of studies built on shallow theoretical foundations and blurred the differences between communities of practice and other social phenomena concerned with knowledge or learning. The resulting confusions are examined in the following section.

Some confusions in the literature can be traced to the similarity of the concept of community of practice to other social structures that are related to knowledge and learning; the most prominent are listed in Table 3. The first is Constant's (1980) concept of communities of technological practitioners, which Brown and Duguid (2001: 210) consider an earlier and independent derivation of the community of practice concept. However, Constant's communities are actually closer to Brown and Duguid's own concept of a network of practice (defined simply by a shared practice), than to Wenger's concept (which is defined by direct engagement between participants). Constant's aim is to build a Kuhnian model to explain a technological revolution, specifically the advent of turbojets. Yet his communities are defined as people sharing a narrow technical specialty, rather than people sustaining direct engagement.

| Community of technological practitioners | 'Utilization of a community of practitioners as a primary unit of historical analysis nevertheless does promise to generate basic insights for the history of technology. A community of technological practitioners, moreover, may be analyzed in turn as an aggregation of individuals or of firms, just as a scientific specialty may be analyzed as an aggregation of individuals or of labs and departments' (Constant 1980: 9). |

| Occupational community | '[A] group of people who consider themselves to be engaged in the same sort of work; who identify (more or less positively) with their work; who share a set of values, norms and perspectives that apply to, but extend beyond work related matters; and whose social relationships meld the realms of work and leisure' (van Maanen and Barley 1984: 295). |

| Occupational subculture | Occupational subcultures comprise unique clusters of ideologies, beliefs, cultural forms and practices that arise from shared educational, personal and work experiences of individuals who pursue the same profession within the overarching organizational culture of a single workplace (Trice 1993). |

| Epistemic culture | '[T]hose amalgams of arrangements and mechanisms – bonded through affinity, necessity and historical coincidence – which, in a given field, make up how we know what we know' (Knorr Cetina 1999: 1, italics in original). |

| Network of practice | 'Networks of practice are made up of people that engage in the same or very similar practice, but unlike in a community of practice, these people don't necessarily work together [yet] such a network shares a great deal of common practice. Consequently, its members share a great deal of insight and implicit understanding. And in these conditions, new ideas can circulate. These do not circulate as in a community of practice, through collaborative, coordinated practice and direct communication. Instead, they circulate on the back of similar practice (people doing similar things but independently) and indirect communications (professional newsletters, listservs, journals and conferences, for example)' (Brown and Duguid 2000b: 28). |

Next is van Maanen and Barley's (1984) notion of occupational community, whose definition is shown in Table 3. Crucially absent from this definition is any mention of mutual engagement, which for Wenger (1998) is the only necessary condition for the existence of a CoP, irrespective of members' occupations. Moreover, since communities of practice can have interdisciplinary membership (e.g., Goodwin et al. 2005), they cannot be considered local portions of a broader occupational community.

As mentioned earlier, the concept of occupational community is famously used in Orr's (1990) ethnography of tech reps, even though they formed a local group who regularly engaged in sharing stories, i.e., a CoP, while simultaneously belonging, as Brown and Duguid (2001: 206) point out, to a much larger occupational community.

Trice's (1993) concept of occupational subculture is another that superficially bears some resemblance to the concept of community of practice. However, Trice's concept, like Constant's and van Maanen and Barley's, does not require or guarantee that members of these groups actually engage with each other. Therefore, though they may share a profession, they cannot cohere into a community without regular engagement.

Brown and Duguid's (2000b; 2000c) concept of network of practice has attracted much attention, possibly because it provides a theoretically legitimate way of talking about Internet-based structures that could be easily taken for virtual communities of practice (Wasko and Faraj 2000; Wasko and Teigland 2004; Wasko et al. 2009). However, this is not the original intent of the concept, as the authors themselves explain. They acknowledge their concept is close to van Maanen and Barley's (1984) occupational community, using at one time the metaphor of a 'virtual guild' (Brown and Duguid 2000b: 29), but they wish to re-direct attention from the 'community' aspect of such groups to the shared practice. They see networks of practice as extended epistemic networks where practice provides a common substrate which makes them capable of effectively sharing a great deal of knowledge, even if most of their members 'will never know, know of, or come across one another' (Brown and Duguid 2001: 205). Thus, a key strength of the concept is spatial extension. Two haematologists who have never met would be part of the same network of practice because of the highly specialized practice they both belong to (Brown and Duguid 2000b). Indeed, Duguid (2005: 113) defines a network of practice as 'the collective of all practitioners of a particular practice'. This is distinctly different from a community of practice, where the membership criterion is direct and sustained engagement.

However, by definition, networks of practice contain embedded communities of practice: high density sections of the network formed by practitioners who actually engage with each other regularly and thus develop much stronger ties than those prevalent over the network (Brown and Duguid 2000c). This suggests that a viable search strategy for communities of practice is to examine the social network structure of a known network of practice for areas of high-density. Fleming and Marx (2006) have tried this by examining the social networks of co-authored patent-holders in the US for the 25-year period starting in 1975. This has allowed them to actually sketch existing networks of practice and their embedded communities of practice and to link them to increasing innovation, particularly in Silicon Valley and Boston.

Lastly there is Knorr Cetina's (1999) concept of epistemic culture, which Brown and Duguid (2001: 205) assess as equivalent to a network of practice by pointing out it makes no distinction between groups of scientists working closely together on a regular basis and same-discipline scientists who rarely meet or know each other. Hence, a local portion of an epistemic culture might qualify as a community of practice, but not the complete culture. As before, the crucial distinction is that of direct engagement, while both network of practice and epistemic culture require only a common practice, however specialized.

The concepts reviewed in this section have caused some confusion in the literature, but in the end they designate different realities (see Cox 2008 for a useful critique). Greater confusion has been caused by alternative or competing designations for communities of practice, which are reviewed next.

Another manifestation of interpretative viability can be discerned in the appearance of a number of alternative designations for communities of practice. Some authors have introduced new names for various learning groups in organizations, which upon close examination appear to differ very little from the earlier concept of CoP, thereby contributing to the conceptual confusion in the literature.

Boland and Tenkasi (1995) acknowledge borrowing Lave and Wenger's (1991) concept of community of practice, to which they added their own nuances. They propose the term community of knowing to describe communities of specialised or expert knowledge workers in knowledge-intensive firms. Arguably, they could have referred to a 'community of practice of experts' to avoid the introduction of a new designation.

Other authors have differentiated themselves from the Wenger framework by making absence of management direction or support a necessary condition for a true community of practice and proposing new designations for groups that display all the properties of communities of practice, yet develop with management's blessing and support.

For instance, Büchel and Raub (2002) introduced the concept of knowledge networks which they argue extends beyond the traditional concept of community of practice. The authors propose four variants of this concept: 'hobby' networks, 'professional learning' network, 'business opportunity' network and 'best practices' network. They contend only the first two conform to the traditional concept of community of practice (2002: 589), but it is the last two that can bring about organizational benefits. Their position is that once management support is received the community ceases to be 'informal' and 'voluntary' and therefore ceases to be a community of practice.

Similarly, Barret et al. (2004: 1) establish a distinction between communities 'which are... voluntary in terms of participation and those with a more managed membership', with only the former being considered communities of practice. They use the umbrella term 'knowledge communities' to cover voluntary and managed communities and they also include constellations of communities of practice (Wenger 1998).

Stork and Hill (2000) also present informality as a necessary condition of a community of practice. They describe a community of information technology managers at Xerox, which began with an initial roundtable two-day meeting, decided to meet again in two months and thereafter met every six weeks. They took the name Transition Alliance and agreed their domain was to orchestrate a major transition from Xerox's proprietary technology to more open industry standards. Senior management fostered the launch of the Alliance and was supportive of it, but did not try to control it or request deliverables. For instance, attendance to meetings was not mandatory. Still, Stork and Hill argue that because the group was deliberately established by senior management, it did not qualify as a community of practice (2000: 65), but as a new organizational group they labelled a 'strategic community'. However, the large amount of freedom this group enjoyed from the start, the fact that members all shared the same practice and were all stakeholders in the technological transition and the crucial fact that they interacted regularly both in and between meetings would suggest that, from Wenger's perspective, the group did evolve into a true community of practice. (In fact, both Wenger and Thomas Davenport wrote letters to the Editor to suggest this.)

These various authors' insistence on informality as a defining condition of a true community of practice is contradicted by Wenger's (1998) study of claims processors, which showed mutual engagement and not informality, to be the essential condition. Any workgroup engaged in a specific domain of knowledge will over time evolve into a community of practice; that is, it will develop an indigenous practice that allows it to get the job done, even if the workgroup is formally established by management, as was the claims processors unit, which boasted a supervisor and an assistant supervisor (1998: 75). Still, because a community of practice defines itself through engagement, its boundaries will not necessarily match institutional boundaries, because membership is not defined by institutional categories. It is in this sense that Wenger describes communities of practice as essentially informal, but he explicitly rejects the view that communities of practice can never have a formal status.

Further evidence against informality as a defining condition is provided by several recent studies of strategically-important communities of practice supported or even intentionally launched by management (Swan et al. 2002; Thompson 2005; Anand et al. 2007). These studies, which are reviewed in below, support Wenger's position that communities of practice can assume 'knowledge stewarding' responsibilities in organizations if management is socially sensitive and is careful not to stifle their self-organizing drive (Wenger 1999; 2000a). Intra-organizational communities of practice are ubiquitous, a consequence of engagement being their root cause (Wenger 1998). The problem is that not all communities of practice are equally relevant to managers; most are only important to members, helping them to cope with a particular class of problems at work. Much more exceptional are communities of practice with the potential to have a strategic impact on the business, whose main interest is aligned with managers' priorities and who are actually recognised and supported. The knowledge management agenda of detecting or launching such communities of practice has resulted in a large number of publications displaying minimal theoretical support.

A final example to close this section is Korczynski's (2003) concept of communities of coping. These are informal groups that emerge among service workers to support each other in dealing with the stress and discomfort caused by having to deal with irate customers, for instance in call centres. In choosing this label, the author acknowledges adopting Brown and Duguid's (1991) language, but still considers these groups as a different structural form without clearly articulating the difference. In a recent study, Raz (2007) uses participant observation and interviews to examine work in three Israeli call centres where employees not only support each other but teach new members how to work the system. This study indistinctly uses both labels, communities of practice and communities of coping. It finds that the key driver for the emergence of the community is to help its members deal with the contradictions of their work, such as the tension between time spent on each call and quality of customer service. However, Wenger's (1998) ethnography of claims processors gives ample space to describing how that co-located community of practice helped employees to cope with management demands, including dealing with irate customer calls (1998: 24). There thus seems to be little reason for creating a new label to highlight this previously identified aspect of the enterprise of a community of practice.

Some authors argue that when Lave and Wenger (1991) refer to a community of practice they use this designation just as an analytic viewpoint or a conceptual lens for examining social learning processes, but it was not their intention to name a stable group (Contu and Willmott 2003; Cox 2005). However, taking at face value Lave and Wenger's ethnographic studies, as well as Orr's (1990) minutely detailed ethnography, it seems implausible to argue the concept does not identify a particular type of social structure. The potential difficulties in clearly establishing their membership, the relations between them, or the exact contents of their practice should not be exacerbated into denying their reality as stable social structures with identifiable characteristics that members are aware of belonging to.

Gherardi, Nicolini and Odella (1998) similarly argue from a constructivist perspective that there is a danger of reifying communities of practice. They reject the view of a community of practice as a community with defined boundaries, established behavioural rules and canons. They argue that communities of practice are just one of the forms of organizing, specifically, organizing for the execution and perpetuation of a practice.

'In other words, referring to a community of practice is not a way to postulate the existence of a new informal grouping or social system within the organization, but is a way to emphasise that every practice is dependent on social processes through which it is sustained and perpetuated and that learning takes place through the engagement in that practice' (1998: 279).

By declining to reify the community, Gherardi et al. seem to reify the practice instead, as if the practice had a life of its own, independent from this or that specific group of practitioners. Cook and Yanow (1993: 378) provide a good counterargument by noting how the Concertgebouw Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic perform the same Mahler symphony differently (as any Mahler fan knows, this is the case even under the same conductor).

Wenger's (2002: 2340) position is that a community of practice is an analytical category but also a real social structure:

'Yet, you can go into the world and actually see communities of practice at work. Moreover, these communities are not beyond the awareness of those who belong to them, even though participants may not use this language to describe their experience. Members can usually discuss what their communities of practice are about, who else belongs and what competence is required to qualify as a member.'

Another frequent critique concerns Wenger's (1998) treatment of power issues within communities of practice and what is regarded as a shift from an emancipatory discourse in his seminal work with Lave, to a managerialist discourse of performance in his later publications.

Specifically, Fox (2000) critiques Wenger (1998) for insufficiently addressing unequal relations of power and for explaining power only as an aspect of identity formation and not as an aspect of practice per se. Marshall and Rollins (2004) also underscore the importance of power and politics in the process of negotiating meaning. They critique Wenger (1998) for mentioning without further elaboration the potential struggles for the appropriation and fixing of meaning within communities of practice. Cox (2005) argues that mundane workplaces, such as those chronicled by Wenger (1998), trigger alienation and suggests communities of practice are informal groups of employees with an agenda of active opposition to management's control. However, this is a somewhat strained extrapolation of Wenger's observation that by inventing a practice, the claims processors community of practice aimed to get the job done in a manner satisfying to themselves.

For their part, Contu and Willmott (2000: 271) critique the latter Wenger for his support for a managerialist agenda:

The account of learning presented in Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems [Wenger 2000b] can be interpreted as a shift from earlier participation in an analytic community engaged in practices that aspire to enhance mutual understanding for purposes of emancipation (Lave and Wenger 1991) to participation in a community that is primarily preoccupied with improving prediction and control for purposes of improving performance.

In point of fact, Wenger argues communities of practice cannot be managed in the usual sense of the word; they can be manipulated or coerced into submission, but managing the practice of a community of practice, in the narrow sense of exercising control over it, is not possible:

'[T]he power - benevolent or malevolent - that institutions, prescriptions or individuals have over the practice of a community is always mediated by the community's production of its practice. External forces have no direct power over this production, because in the last analysis (i.e., in the doing through mutual engagement in practice), it is the community that negotiates its enterprise' (Wenger 1998: 80).

Indeed, because a community of practice is essentially an informal group, it always has the option of removing itself from management's control if it feels its enterprise is threatened. Studies by Gongla and Rizzuto (2004) and Pastoors (2007), reviewed in the next section, give evidence of employees joining bootlegged or underground communities of practice to evade management and freely pursue their own interests. Nevertheless, Wenger also qualifies that arguing communities of practice produce their own practices is not to assert that they are an emancipatory force (1998: 85).

Wenger's treatment of power issues is, in fact, consistent with his broader theoretical framework. He sees communities of practice as wielding power because they socially define competence and identities (Wenger 2000b). Thus, a person may decide whether he or she wants to belong to a particular community (i.e. learn its practice), but has a limited capacity as an outsider (or even as full member) to change the practice of the community. On the other hand, a community of practice is powerless before an individual who does not recognize its authority and is not interested in joining.

It ought to be noted that this competence-defining role of communities of practice is also the source of their greatest weakness: the danger of becoming insular (Wenger 2000b) and losing touch with the broader organization and market environment (Thompson 2005).

Wenger's (1998) framework thus seems to give coherent replies to the principal critiques that have been levelled at it. Moreover, the framework seems to be enjoying a renaissance, as a growing number of studies are attempting to operationalize it. In the meanwhile, other researchers have gradually made specific contributions to theory, either by confirming insights already mentioned in Wenger (1998), or by extending that framework in particular respects. These contributions are reviewed in the next section.

This section reviews a selection of theoretically-grounded studies, published during the second decade of community of practice literature, that have made significant contributions to our understanding of communities of practice. They are broadly grouped into six areas of current interest: launching communities of practice, managing and controlling communities of practice, boundaries and innovation, identity construction, virtual communities of practice and the concept of community of practice. An overview of these contributions is provided in Table 4.

| Launching communities of practice | Swan et al. (2002): communities of practice used as a rhetoric device to promote change and innovation. Thompson (2005): distinguishes between structural components, which organizations can furnish and epistemic behaviours, which depend on members alone. Anand et al. (2007): identify success factors for launching new practice areas in consulting firms. |

| Managing or controlling communities of practice | Gongla and Rizzuto (2004); Pastoors (2007): communities of practice can and do evade management control. Cross et al. (2006): use social network analysis to measure knowledge transactions and perform targeted interventions in community of practice membership and structure. Meeuwesen and Berends (2007): develop measures of performance of intentionally launched communities of practice. Schenkel and Teigland (2008): use learning curves to measure performance of identified communities of practice. |

| Boundaries and innovation | Hislop (2003): study of seven companies where a technological innovation was promoted by management; found that some communities of practice supported and others hindered the project. Bechky (2003): ethnographic study of difficulties in transferring knowledge across community boundaries. Carlile (2004): identifies three types of boundaries between communities of practice, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic and three processes for spanning each type of boundary: transfer, translation, transformation. Swan et al. (2007): use Carlile typology to examine the role of objects in spanning different boundaries in a study of innovation diffusion in the UK health system. Ferlie et al. (2005): found that epistemic boundaries between discipline-bound health care communities of practice can retard the spread of innovations. Mørk et al. (2008): study of cross-disciplinary R&D medical centre, where new knowledge challenging an established community of practice was marginalized. |

| Identity construction | Ibarra (2003): mid-career transitions require severing ties from former communities of practice and joining new ones. Hara and Schwen (2006): ethnographic study of a public defenders' office developed new community of practice framework consisting of six dimensions. Handley et al. (2007): ethnographic study of identity construction by two junior consultants working at a leading firm. Campbell et al. (2009): case study of the learning trajectory into a community of practice of a middle-aged nurse who made a career change to police officer. Goodwin et al. (2005): ethnographic study of internal boundaries in multi-disciplinary communities of practice in anaesthesia. Faraj and Xiao (2006): emergency boundary suspension in multidisciplinary medical teams. |

| Virtual communities of practice | Bryant et al. (2005): case study of increasing involvement in Wikipedia as an induction into an online community of practice and development of Wikipedian identity. Hara and Hew (2007): case study of community of advanced practice nurses based on a listserv. Zhang and Watts (2008): apply Wenger framework to online community focused on back-packing. Murillo (2008): systematic Usenet search and detection of four virtual communities of practice displaying Wenger dimensions. Silva et al. (2008): apply the legitimate peripheral participation model to a blog, operationalized as old-timers who enforce local norms. Fang and Neufeld (2009): apply the legitimate peripheral participation model to an open-source software community, finding evidence of strong identity construction/enactment. |

| The concept of community of practice | Cox (2005): critical review and comparison of four seminal studies. Roberts (2006): literature review that highlights the limits of communities of practice as a knowledge management tool and identifies issues that have been insufficiently addressed in research. Hughes (2007): critique of Lave and Wenger (1991) that questions whether their model extends beyond the cases they examined. Amin and Roberts (2008): critique the status of communities of practice as an umbrella concept and propose a typology of four modes of knowing in action. Gherardi (2006): proposes new definition and theoretical framework for communities of practice based on a full-length ethnography of three interacting communities of practice in a construction site. Hara (2009): proposes a new definition and theoretical framework of communities of practice based on ethnographic study of a public defenders' county office. |

Several recent studies examine whether communities of practice can be launched, or more precisely, whether a group initiated by management has a reasonable chance of developing into a true community of practice. The answer appears to be a cautious yes, if the necessary structural elements are provided (McDermott 2000; Wenger et al. 2002; Thompson 2005). However, management attempts to control communities of practice, for instance by demanding certain deliverables, can simply transform them into organizational units (teams or task forces), make them go underground (Gongla and Rizzuto 2004) or make them conform to the official line with little real learning (McDermott 2007).

Swan, Scarbrough and Robertson (2002) provide an example of highly nuanced managerial intervention, a case study of a medical community of practice convened or promoted by administrators of a health organization as a vehicle for a radical innovation in the treatment of prostate cancer known as brachytherapy. These managers envisioned their role not quite as launching but as facilitating the construction of a new multidisciplinary community engaged in brachytherapy practice. They explicitly addressed constitutive dimensions of communities of practice such as a well-defined domain of knowledge, identity enhancement, networking and knowledge brokering. Thus, even though managers were relatively powerless before established medical professionals, they were able to deploy the theory and the discourse of communities of practice to promote the adoption of an innovative procedure. The study also provides a textbook example of the use of fashionable management discourse to promote change (Benders and van Veen 2001).

Thompson (2005) makes a contribution to the community-of-practice-launching debate by distinguishing between structural parameters and epistemic behaviour adopted from Wenger's (1998) indicators (see Table 2) and proposing that management can manipulate them to launch a community of practice. The study relies on participant observation and interviews to examine a co-located community of practice at a large, information technology hardware and services firm. The forty-member group was formally established as a creative Web-design agency, exempt from the commercial and procedural restrictions of the parent organization. It enjoyed heavy corporate sponsorship of information technology infrastructure and culturally symbolic artefacts (pool tables, video games, bean bags, etc.) conducive to a relaxed, informal and creative work environment. The author reports strong group identification and epistemic interaction, relying on Wenger's (1998) framework to assess the emergent tight-knit group as a community of practice. However, the organization tried to capitalise on the group's success with the addition of 140 new in-training participants, which required formal documentation of procedures (hitherto unnecessary because of the group's small size) and other prescriptive measures such as controls on billable versus non-billable activities. This brought about the demise of the original community of practice, as members quickly withdrew identification and commitment from the new, more formalised structure. These findings are in line with Wenger's (1998) position that communities of practice can be supported or nurtured but not controlled. Furthermore, they refine Wenger's framework by distinguishing between two dimensions which managers must pay attention to when launching communities of practice. The first, are seeding structures, including shared symbols, artefacts, monuments, tools and boundary objects, that can be comprised under the Wenger concept of shared repertoire and which organizations can subsidize and make available to potential community of practice members. Second and more difficult, is encouraging members to interact within these structures and among themselves, i.e., to engage in practice or perform the epistemic behaviours which over time will give rise to a community of practice. The article also maps these dimensions onto Wenger's indicators, with epistemic behaviours corresponding to Indicators 1-9 and structural components to Indicators 10-14.

Anand et al. (2007) investigate the success factors for launching new practice areas within management consultancies. They characterize these as innovative knowledge-based structures and they expressly identify them with communities of practice as portrayed in a vignette of a consulting company in the book by Wenger et al. (2002). Their multiple case study was conducted at four consulting firms and included a total of twenty-nine cases of practice areas, including both successful and unsuccessful efforts. This led them to identify four critical generative elements: socialised agency (a consultant's drive to create a new practice area as a key career-progression move), differentiated expertise (a new and distinctive body of professional knowledge), defensible turf (persuading others of the market relevance of the new practice area) and organizational support (resources, personnel and sponsorship to nourish the new practice area). All instances of successful practice area creation displayed socialised agency as the process catalyst. In what the authors called emergence step, agency combines with one of the other three critical elements, which gives the new practice area visibility within the firm. But the new structure only becomes viable if the other two elements are also added, in what is called the embedding step. The study identified three equally robust pathways whereby a practice area can be born depending on which of the three elements initially combines with socialised agency: the expertise-based pathway (when a consultant develops new expertise), the turf-based pathway (when a client opportunity provides a consultant with enough market power) and the support-based pathway (when firm leadership nominates a consultant to create a new practice top-down). The study found as many instances of successful management-launched communities of practice, through the support-based pathway, as of bottom-up emergence through the other two pathways. Study findings thus complement Thompson's (2005) single firm case study and contrasts with previous literature about the immunity of communities of practice to management control (Gongla and Rizzuto 2004; Pastoors 2007).

In sum, there is empirical support to claims that communities of practice can be intentionally designed and launched and there is certainly no shortage of step-by-step guides (e.g., McDermott and Kendrick 2000; Wenger et al. 2002; Plaskoff 2003; Saint-Onge and Wallace 2003; Moran and Weimer 2004).

On the other hand, several studies document the reluctance of community of practice members to maintain their commitment when management attempts to control the learning agenda of the community or request specific deliverables. An example is the demise of Thompson's (2005) community, described earlier. In addition, there is a systematic study by Gongla and Rizzuto (2004) who tracked the disappearance, over a six year period, of twenty-five organizational communities of practice at IBM Global Services. In many cases, the demise of communities of practice can be attributed to natural causes, as members' interests and commitments shift. However, they also found that management intervention can cause the transformation or demise of a community of practice in two ways: first, management interventions can transform a community of practice into an official organizational unit, like a programme, a project or a practice. Henceforth, decisions about (former) community objectives, agenda, deliverables and membership are made by management, not by members. Second, a community that faces increasing management control may decide to 'remove itself completely from the organizational radar screen' (2004: 299) and continue to function off-site or outside work hours in order to preserve its independence and avoid management-imposed assignments.

In a similar vein, Pastoors (2007) provides a case study of a large information technology consultancy that ran a strong internal programme of institutionalised communities of practice. Management assigns consultants to different communities of practice without paying much attention to their preferences. communities of practice are highly formalised and operate according to strict guidelines with respect to roles, communication and performance evaluation. Moreover, consultants' career advancement is contingent on their performance in their assigned community of practice. The study found consultants were not motivated to spend extra time or effort in their assigned communities of practice. Instead, they joined and spent time on bootlegged, unofficial communities of practice where they were free to pursue their passion.

An unusual angle, with respect to management control, is provided by Cross et al.'s (2006) study of targeted interventions to improve performance of communities of practice. They use social network analysis to map the existing relationships between community members and the volume of knowledge transactions flowing through these social ties. Coupled with background information of member expertise, social network analysis can reveal community of practice members who are excessively connected and thus bear a disproportionate burden of consultations, usually repetitive. Social network analysis can also detect functional and geographical silos where good practices are not being effectively communicated due to lack of connections between some members. Similarly, such analysis can locate peripheral individuals in the community who have high experience and expertise but are relatively isolated and hence unable to fulfil their potential. Specific interventions that companies can use include revising the formal roles of certain community of practice members, using electronic profiling systems to communicate member expertise more broadly and transferring or rotating specific experts to particular geographical areas. Post intervention member surveys, again interpreted through social network analysis, can then quantify the knowledge-transfer improvements and thus validate the interventions.

Another dimension of management control is the attempt to measure the performance of intentionally launched communities of practice. Various indicators have been tried, including levels of community of practice activity, development of new products and processes, knowledge sharing behaviours, messages posted in discussion boards, etc. A related concern has been to measure the benefits of community of practice activity to the launching organization (Lesser and Storck 2001; Fontaine and Millen 2004).

Meeuwesen and Berends (2007) provide a case study of four intentionally launched communities of practice focused on advanced manufacturing technologies at Rolls Royce. The communities were formed by management-designated experts, about ten in each. All of them went through a day long workshop where they learned about the characteristics and benefits of a community of practice and a dedicated facilitator was assigned to each. An important caveat is that the communities of practice were not all launched simultaneously: at the time of the evaluation the youngest was a month old and the oldest (and most successful) over three months old. The company evaluated the performance of the communities of practice using member surveys with scales for measuring community of practice activities such as internal and external knowledge sharing, contributions to the online bulletin board and meeting frequency. Other scales measured outcomes, such as number of products, procedures and processes adopted, that were originally mentioned in the community of practice.

The study found that intentionally designed communities of practice indeed began to function as such and provided some benefits to its members. However, the results were uneven across the four communities of practice; in particular, no correlation was found between the level of community of practice activity and the outcome variables. Moreover, the study found that the structural elements of communities of practice (the Wenger dualities of participation-reification, identification-negotiability, local-global and designed-emergent) take time to develop and to become balanced. A limitation of the study is lack of information about ground rules, deliverables, or the time members were allowed to commit to the community of practice. Hence, even though the study is grounded upon Wenger's (1998) framework, it is difficult to decide whether these communities are true communities of practice, cross-disciplinary teams or committees, a failing displayed by similar other studies of community of practice performance (e.g., Chua 2006; Verburg and Andriessen 2006; Probst and Borzillo 2008).

Schenkel and Teigland (2008) used learning curves to measure the performance of four co-located communities of practice at a large construction site. To identify them, they relied on the Wenger dimensions of mutual engagement, joint enterprise and shared repertoire. They developed a performance measure using the learning curves associated with the number of recorded deviations from defined standards. They found all learning curves had negative slopes, indicative of a decreasing number of deviations, which in turn spoke of improving community of practice performance. One community broke the pattern, though, displaying positively sloped learning curves for a time and then plateauing. The authors traced this anomaly to a disruption in communicative processes caused by a physical move of the group to a new location that additionally split the group between two separate locations, making face-to-face exchanges a rare occurrence.

Reviewed studies thus seem to confirm the ability of communities of practice to evade management control when they feel their jointly negotiated enterprise is threatened. Management can, of course, take over a community of practice but Gongla and Rizzuto (2004) are correct in pointing out this will just turn it into a committee or task force, which is unlikely to draw the same level of enthusiasm from members.

Recent studies have also examined the role communities of practice sometimes play in retarding or inhibiting innovation. This is a relatively new angle given the many studies that present innovation as a defining feature of communities of practice (Orr 1990; Brown and Duguid 1991, 2000a; Brown and Grey 1995; Prokesch 1997; Swan et al. 1999; Wenger 2000b; Lesser and Everest 2001; Fontaine and Millen 2004). Indeed, the studies by Anand et al. (2007), Meeuwesen and Berends (2007) and Schenkel and Teigland (2008) all provide evidence of innovation taking place inside communities of practice and specific measures of innovation are often used in studies of communities of practice performance. Yet there are also studies showing more mixed results.

For instance, Hislop (2003) reports longitudinal case study evidence from seven companies implementing technological innovation projects, specifically multi-site, cross-functional management information systems. He uses Brown and Duguid's (2001) definition of communities of practice as groups possessing common knowledge/practices, shared identity and common work-related values, which results in his identifying communities of practice with local business units and/or business functions. The study found communities of practice that strongly supported the innovation project, specifically those that had a strong information technology identity which valued information systems. Other communities of practice hindered the innovation because they valued their local autonomy, were resistant to management's centralising agenda and were reluctant to share knowledge with other units. These results are congruent with Wenger's (2000b) views on boundaries and identities, but are limited by the condensed definition of community of practice and the study's generalised characterization of each of the company's business units and functions as communities of practice.

Wenger (2000b) argues that community of practice boundaries deserve special attention because they connect different communities of practice and because they offer distinct learning opportunities. Radical insights often arise at the intersection of multiple practices. Yet the process is not without tension and conflict. Researchers have chronicled instances of successful innovation at the boundaries of different communities of practice, but also instances where such boundaries have retarded the spread of innovations. In talking about moving knowledge across communities of practice or networks of practice, Duguid (2005) introduces a useful distinction by talking about the epistemic and ethical entailments of practice: the former refers to the challenge of translating knowledge held within one practice into a different one; the latter refers to the political barriers that may make exporting such knowledge (or even importing it) unacceptable to one of the communities.