vol. 16 no. 3, September, 2011

vol. 16 no. 3, September, 2011 |

||||

Chance encounters with information, objects, or people that lead to fortuitous outcomes are an integral part of everyday information behaviour. Erdelez stresses that '[r]esearch-driven and anecdotal evidence suggests that users often find interesting and useful information without purposeful application of information searching skills and strategies' (2004: 1013). Some researchers have expressed concern that opportunity for this type of encounter might be reduced in the context of technologically facilitated information behaviour (Thom-Santelli 2007). In response, work in information systems has proposed the development of interfaces that support or enable serendipity (Thom-Santelli 2007; Toms and McCay-Peet 2009). The effective integration of serendipity in information technology, however, requires an understanding of how people experience serendipity in everyday environments. We propose to address this gap by developing a comprehensive model of serendipity in everyday information seeking. We begin the paper with a review of the literature on serendipity, most of which is based in the context of scientific discovery. We identify the core characteristics of serendipity expressed in this literature, and contrast these with serendipity as described in non-elicited, natural descriptions of accidental encounters collected from blogs using keyword searches. The result is a model of serendipity in everyday information seeking.

Past studies of everyday serendipity and chance encounters have taken three approaches. In some cases, interviews or surveys were used to elicit retrospective reports of such events (e.g., Erdelez 1997; Pálsdóttir 2010; Yadamsuren and Erdelez 2010). In other research, descriptions of chance encounters emerge as part of a larger exploration of information behaviour (e.g., Foster and Ford 2003; Williamson 1998). Finally, in some research attempts are made to trigger or elicit such events (e.g., Erdelez 2004; Toms and McCay-Peet 2009). Retrospective accounts produced for the purposes of research provide some insight, but their usefulness is limited by the demand characteristics of the research context and the retrospective nature of the recall. The event elicitation approaches allow control over the situation in which a chance encounter is evoked, but it has proven difficult to provoke serendipity, perhaps because the artificial situations have limited meaningfulness to the participants, who therefore lack the deeper involvement that may be required for serendipity (Erdelez 2004).

In response to these limitations, Erdelez (2004) calls for approaches that are based on participant self-generated data (Gross 1999). In the current study, selective blog mining is introduced as an alternative method of data collection that addresses these concerns, focusing on naturally occurring descriptions of chance encounters that are created by bloggers independent of the study. The accounts that make up our dataset were written by self-motivated bloggers for an unspecified audience. While many of these texts do not address all of the nuances of a chance encounter episode, they offer realistic retrospectives produced by the individual who experienced the encounter. Analysis of these descriptions allows us to explore the contextual factors associated with experiences of serendipity.

Our paper has the following three goals: 1) to test the effectiveness of an alternative data collection method for serendipity research; 2) to propose a more refined conceptual model that outlines the facets of serendipity; and 3) to better understand serendipity in the context of everyday information behaviour. The proposed model is an extension of previously presented findings (Rubin et al 2010).

In 1997, Gup lamented the 'end of serendipity', recalling with fondness his childhood experiences coming across interesting tidbits of information while flipping pages in the encyclopedia. In his article, Gup (1997) expressed concern that the 'vastly more efficient' pursuit of information supported by computers would rob us of the 'random epiphanies' and 'accidental discoveries' that are limited in an information environment that is tailored to our needs and where 'nothing will come unless summoned'. Gup is not alone in his concerns, which are echoed by others (including McKeen (2006)). Gup has an antidote to lost serendipity, expressed in this fantasy:

One day I will produce a computer virus and introduce it into my own desktop, so that when my sons put in their key word – say, 'salamander' – the screen will erupt in a brilliant but random array of maps and illustrations and text that will divert them from their task. (Gup 1997: A52)

Obviously, for Gup serendipity amounts to random encounters that draw us away from the task at hand. Others who attempt to build serendipity back into the online environment take a different approach, and implicitly embrace a different notion of serendipity. BananaSlug is 'all about serendipity' billing itself as the 'Long Tail Search Engine'. The search engine adds a random factor to a regular Google search by 'throwing in' an unrelated (and randomly selected) word from a category of the searcher's choice. The inclusion of this random factor effectively re-orders the search results, bringing to the forefront results that the searcher might not have noticed in a traditional search. In this case, serendipity apparently refers to unexpected noticing of information related to a current task. AssistedSerendipity does not rely on randomness at all, instead delivering to the user information they might not otherwise access: the purpose of this mobile phone app is to track the male/female ratio at locations you specify, notifying you when the 'scales tip in your favour', presumably so that you can increase your chances of meeting someone of the sex of your choice. SerendipitySeattle marks the locations of potentially interesting, and presumably unnoticed, events such as theatre, talks, music 'and more' on maps on mobile devices: instead of connecting users to people, this app connects them to events they might not otherwise know about. Inception also relies on enriching the information environment to create 'serendipity'. This application is a 'social browser' that 'tells you what to browse next' by gathering and sharing links from other users on the social web.

Eagle and Pentland (2005) developed a system for enhancing the possibility of social encounters with others of similar interests, and Newman et al. (2002) propose a system that will allow for opportunistic or serendipitous discovery of networked resources such as printers, cameras, or microphones. These systems work by empowering our devices to automatically scan the environment for relevant information: other users who have expressed similar interests (Eagle and Pentland 2005) or nearby networked devices (Newman, et al. 2002). Google plans to take this one step further: at TechCrunch Disrupt in San Francisco on September 28 2010, Google CEO Eric Schmidt announced that the company was building a 'serendipity engine': 'autonomous search' that operates in the background and without your direction 'while you are not even doing searching', drawing your attention to things that you do not know, that would (according to your past search history and expressed relevance) interest you (2010). (This new prototype of search engines heavily relies on personal data and continues to raise privacy concerns.)

Something, however, does not sit quite right with these applications, and Google's foray into the serendipity game has engendered a particularly strong response. As Farrar observes, Google stands to 'end serendipity (by creating it)' (2010); Carr echoes this sentiment: 'Awesome! I've always thought that the worst thing about serendipity was its randomness!'(Carr 2010).

There does seem to be something inherently contradictory in the attempt to 'program' serendipity: after all, at the very core of the term is the notion of chance, or unexpectedness. The sense that the online environment is increasingly determined and predictable promotes a widespread feeling that serendipity is threatened. The perspective seems to be that effective search engines, narrow-casting, and an increasingly tailored information environment are detrimental to the experience of serendipity in everyday life. What is really meant, however, by the term serendipity in these discussions? Or, more to the point, what do we need to build back into the environment to promote serendipity? The answer to this question relies on a fuller understanding of the nature of serendipity, particularly in the context of everyday information seeking. In order to create an online environment that promotes everyday serendipity, we need to know more about how people experience serendipity, what triggers serendipitous encounters, and the circumstances that promote serendipity.

As many have noted, Harold Walpole coined the term serendipity in 1754 (Merton and Barber 2004). The word languished largely unused until the mid 1900s when it was adopted as an apt descriptor of the process of accidental or unplanned discovery in the scientific context (Merton and Barber 2004). Since then, the term has steadily risen in popularity and expanded in use, so much so that it was voted UK's favourite word in 2000 (BBC News 2000).

Despite the popularity of the word itself, serendipity remains elusive and difficult to define. The word derives loosely from the tale of the Princes of Serendip, which chronicles the adventures of three traveling princes whose notable powers of observation and deduction lead them to accurate, insightful, and surprising conclusions. Walpole's definition of serendipity highlighted some aspects of the story; that of accident, or surprise, and sagacity, while obscuring others, notably that the story relies on the princes' keen powers of observation that are employed independently of any particular personal goal (Merton and Barber 2004). The examples that Walpole used to illustrate the concept make clear that he intended serendipity to entail two things: the accidental encountering of information and an outcome of the information encounter that is the solution to a personally relevant problem, question, or concern, either pre-existing, or resulting directly from the information itself. Although there are certainly disagreements as to the precise nature of serendipity, all accounts agree that the following two aspects are central: serendipity necessarily involves a chance observation or encounter where a fortuitous outcome is critical (see Merton and Barber (2004) for a comprehensive discussion of the meaning of serendipity).

Although Walpole's original examples relate to his own life and not the realm of science, the word came to refer almost exclusively to a particular sort of discovery in scientific research; discovery emerging out of chance observation (e.g., Andel 1994; Meyers 1995; Rosenman 2002). There is, not surprisingly, given the vague nature of the word, some debate regarding what constitutes a serendipitous scientific finding. In particular, some have distinguished serendipity from pseudo-serendipity on the grounds that the former necessarily involves accidental and fortuitous discoveries that emerge in the course of an unrelated task (Andel 1994; Roberts 1989). Among scholars who make this distinction, for example, the discovery of penicillin is identified as an example of pseudo-serendipity because, while the relevant observation was accidental and the outcome certainly fortuitous, Fleming was at the time looking for exactly what he found: a new bacterial inhibitor for staphylococcus (Andel 1994). There is no universal agreement, however, on the distinction between serendipity and pseudo-serendipity and, indeed, Andel's example of the latter (Fleming's discovery of penicillin) is cited as an example of serendipity in many other publications on the subject. It appears, therefore, that in the scientific context serendipity requires chance observation and a fortuitous outcome; some examples of serendipity also involve a shift of problem or task so that the outcome is not that which was being sought at the time of the observation, but others do not.

Serendipity in the prosaic context of everyday life is much less studied. There is a small body of research in information studies that examines serendipitous information encounters (e.g., Foster and Ford 2003); some work examines elicited retrospective accounts of these encounters (e.g., McBirnie 2008) and other work has attempted to trigger information encountering in an experimental context (e.g., Erdelez 2004). Little research, however, has examined serendipity as it naturally occurs in everyday environments, especially with respect to accidental encounters that are not restricted to encountering information. As a result, we know relatively little about the conditions that promote serendipitous encounters, the fortuitous outcomes that arise from these encounters and the situational and personal factors that promote everyday serendipity.

The literature on serendipity, does, however, provide some insight into the important aspects of the concept. In the remainder of this literature review we will focus on two: noticing and preparedness.

In her model of information encountering, Erdelez (2000) notes that 'noticing' is the first step, and anecdotal accounts of serendipity typically begin with noticing of the critical observation. Noticing is non-trivial, since much, if indeed not most, of what we encounter in the world is ignored: in fact, we can think of noticing as being the exception rather than the rule in our interactions with the world around us. In examining serendipity it is therefore important to understand how the critical observation comes to be noticed.

There is widespread agreement that some people are more likely to experience serendipity than are others (Erdelez 1999; McBirnie 2008) and this may have to do with individual differences in the tendency or ability to notice. Merton (2004: 257), in his afterword to The Travels and Adventures of Serendipity, notes that dictionary definitions of serendipity almost exclusively refer to a 'faculty, capacity, gift, or talent for making felicitous discoveries by chance'. Walpole (1754) identified himself as someone prone to the sort of 'happy accident' he identified as serendipity:

This discovery I made by a talisman, which Mr. Chute calls the sortes Walpolianae, by which I find everything I want, à point nommé [at the very moment], wherever I dip for it.

Heinström has found that individuals who are extraverted, open and agreeable (personality traits associated with the information seeking style of 'broad scanning') are more likely to encounter information incidentally (Heinström 2006a, 2006b). Within the domain of psychology, serendipity is often associated with creativity, particularly the sort of creativity that involves the association of previously unrelated ideas. Numerous authors have demonstrated that this sort of creativity is enhanced among individuals who show reduced attentional focus, or a broader attentional 'window'; (Ansburg and Hill 2003; Carson et al. 2003; Dorfman et al. 2008; Memmert 2009). In the context of information seeking, Pálsdóttir (2010) has demonstrated that individuals who seek information more actively are also more likely to encounter information, suggesting that encounterers may have a general orientation toward acquiring information. It appears, therefore, that some individuals simply have a propensity toward noticing, and thus being able to take advantage of serendipitous observations.

Environmental or contextual factors may also contribute to noticing. There is ample evidence that contextual factors drive attention at the perceptual level. Difference or change in the environment tends to attract attention. Thus, for example, we tend to notice unique items (e.g., a single red circle in a field of blue circles; e.g., Theeuwes 1994) or sudden changes (such as item onset; Egeth and Yantis 1997). In a complicated auditory environment, and even when closely attending to one signal over competing signals, listeners will react to emotionally loaded or meaningful words on the unattended channel (this is commonly known as the 'cocktail party effect', e.g. Wood and Cowan 1995); and a similar effect has been observed in visual attention (see Shapiro et al. 1997). These results and others like them indicate that although we often decide where to direct our attention, under some circumstances attention is drawn or pulled by aspects of the environment. The environmental or contextual factors that draw attention are in many cases perceptual in nature, but in some situations (as in the cocktail party effect) attention is automatically deployed on the basis of higher-level characteristics such as word meaning (e.g., Pratto and John 1991). It is possible, therefore, that attention could be drawn to items, information, or people in the environment because they are salient (e.g., large, loud, close by, etc.), or because of their relevance to an ongoing problem.

Louis Pasteur famously declared 'chance favours prepared minds'. An examination of the literature on serendipity reveals two kinds of preparation that provide a fertile substrate for serendipity: prior need and background knowledge.

Few if any instances of serendipity as described in existing literature are forward-looking in that the chance observation becomes relevant only at a later point in time. Instead, serendipity typically involves a chance observation that addresses a prior need or question. In some cases of serendipity (note that these are the cases sometimes identified as pseudo-serendipity), the prior need is 'top of mind' at the time of the chance observation, as it was for Fleming in the discovery of penicillin (Andel 1994). Alternatively, the need could be in the background, triggered or resurrected by the chance observation. Thus, for example, the observation that led to the development of the trickle irrigation method was made by an Israeli water engineer when his attention was drawn to a single tree that was growing much taller than its neighbours. When he looked closer, he realized the tree was receiving a constant drip of water from a leaking pipe, and although he had not been thinking of irrigation at the time he noticed the tree, he quickly realized the applicability of his observation to the problem of growing crops with little water (Andel 1994).

Although the existing literature does not specifically address the issue, research in other domains suggests that a prior need may even influence noticing by making relevant observations more salient, or more likely to attract attention. Studies of early attention suggests that high level goals and strategies can affect item salience and very low level (and thus very early) attentional allocation (Chong, et al. 2008; Fecteau 2007; Ferrari et al. 2009). These results are only suggestive, but they indicate that high level goals (e.g., to find an effective treatment for seasonal allergies) could serve to increase the perceptual salience (and thus noticing) of relevant objects, information, or people in the environment (so that, for example, you might suddenly and unaccountably find yourself listening closely to the radio show that had been playing in the background when an allergist comes on to speak).

Background or domain knowledge appears to serve a different purpose in serendipity. There is strong evidence that extensive domain knowledge is a critical antecedent of creativity (e.g., Weisberg 1999). Without domain knowledge, there is no possibility of making the unexpected connection or seeing the unanticipated solution. At the same time domain knowledge can be constraining, locking the individual into accepted or traditional ways of thinking (e.g., Dane 2010). In particular, it appears that domain knowledge supports serendipitous insight when no related focal task is activated. For example, Barber and Fox (1958) document the stories of two scientists, each with the background knowledge required to identify a surprising reaction of rabbits to the injection of a particular drug. One researcher, stalled in other research at the time, noticed and pursued the anomalous observation, while the second, whose primary research program was progressing well, did not. In the context of scientific discovery, the background knowledge that is required is a detailed understanding of the topic of inquiry. In the context of everyday serendipity the relevant expertise may take the form of more prosaic skills and background. Thus, for example, McBirnie (2008) suggests that information literacy plays a critical role in supporting serendipity. In her research, information literacy skills constitute the background knowledge required for serendipitous discoveries.

What we know about serendipity, primarily from the context of scientific research, is this: serendipity involves a chance observation that is instrumental in a fortuitous outcome. Typically, the outcome is relevant to a prior problem, question, or concern. In some cases, the chance observation occurs while addressing the prior problem, while in other cases the chance observation is relevant to a background task or problem that is reactivated by the observation. Serendipity relies critically on noticing the observation. There are individual differences in the capacity to notice in that some people systematically show a stronger information-gathering orientation or an inclination to information encountering (see Erdelez's (1997) notion of super-encounterers). Situational factors may also affect noticing, since it appears that the likelihood of noticing is decreased when an individual is intensely focused on a demanding foreground task or problem. Prior needs may affect noticing by making relevant information more salient and thus more likely to attract attention. Finally, prior knowledge or expertise is critical for making sense of the observation, identifying it as anomalous, surprising, or new, and fitting it into the problem context.

The goal of the current project is to examine examples of everyday serendipity to determine whether these characteristics are evident in accidental encounters in everyday life and to explore the ways in which these characteristics interact in descriptions of accidental encounters.

To obtain naturally occurring accounts of chance encounters, we employed a new method called selective blog mining. We conducted a variety of query searches on GoogleBlog Search (version Beta) between April and August of 2010. GoogleBlog Search retrieves content from blogs that are freely and publicly available, and regularly indexes content from various blog hosting services, including Blogger, Wordpress, Technorati, and LiveJournal. According to their documentation, 'the goal of Blog Search is to include every blog that publishes a site feed (either RSS or Atom). It is not restricted to Blogger blogs, or blogs from any other service' (Google Blog Search Help 2011). Thus, the site provides search over a broad range of blog postings.

Our initial examination of blog postings indicated that although the term serendipity and its word form variations occurred frequently in blog postings, the word was often interpreted vaguely or used in ways that have little if anything to do with its meaning (e.g., simply as part of a name, such as Serendipity 3, the name of a popular restaurant in Manhattan; this may simply reflect the huge increase in use of the word, see BBC News, 18 September 2000). Searches that included the term 'serendipity' or any variants yielded too many false positive results to be useful in constructing the dataset. We did not, therefore, include these terms in our search strings, but instead constructed forty-four queries designed to retrieve instances of accidental encounters (e.g., 'looking for * * * but found'). The selected search queries were bound by double-quotes to allow for the retrieval of blogs containing the exact selected wording. One or more asterisks were placed as 'wild cards' in the search queries to allow for unspecified intervening words in the retrieved accounts, permitting greater flexibility in retrieval A wildcard is defined as 'a character that will match any character or combination of characters in a file name, etc.' (Oxford Dictionary Online 2011). We used a combination of thesauri and online dictionary definitions to inform the formulation of the queries. The three researchers brain-stormed and tested the resulting queries by going through several iterations of performing online searches and assessing the retrieved accounts from blogs.

Many of the queries returned a large number of results, sometimes numbering in the hundreds or even thousands. We reviewed the first hundred results, in GoogleBlog snippet format, for each query. We then identified those accounts that fulfilled the following three criteria, consistent with our understanding of serendipity as described in the literature review. First, the retrieved accounts had to include a clear mention of an accidental find. Second, the accounts had to be rich in nature, offering detail about the context of the find. Third, the account had to be described in light of a fortuitous outcome.

Two coders (the first and third authors who conducted the coding of all the accounts) reviewed the results to determine whether each met these criteria (with the second author providing feedback). Many of the returned results were rejected for the final data set because they did not meet the second criterion, being instead very short or non-descriptive accounts of accidental encounters that were not useful for the purpose of the study. The following is an example:

Example 1:

I was looking for something completely different, but found your Website! And have to say thanks. Nice read ( ID=1).

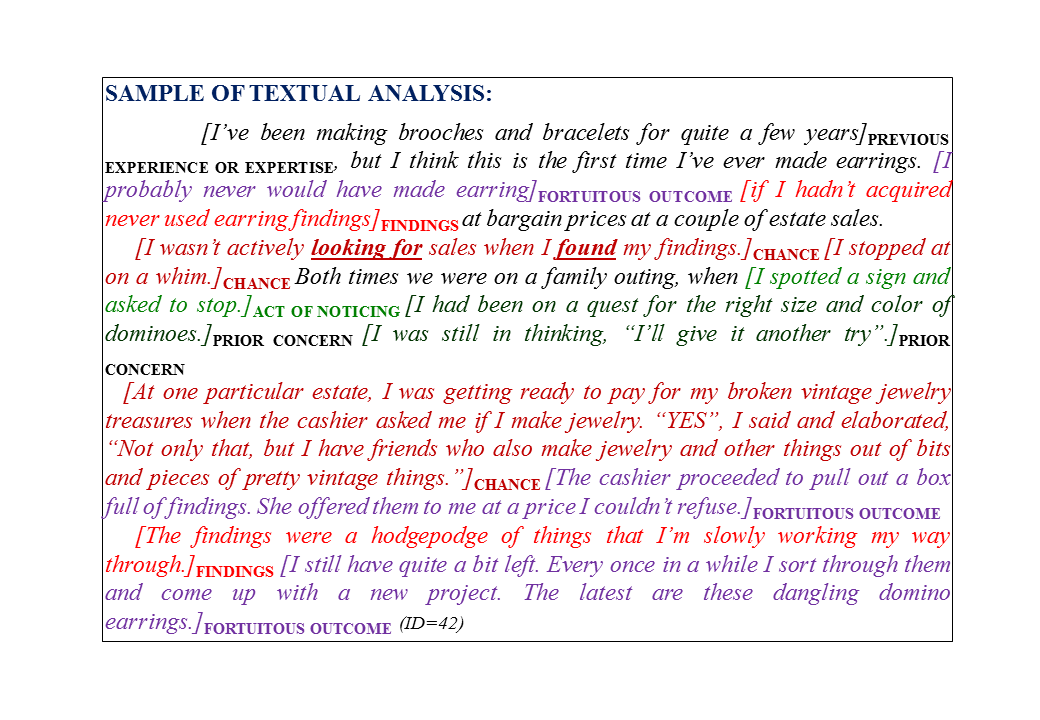

Figure 1 demonstrates a chance encounter that meets the richness criterion. Our analysis of the account is shown by bracketing text segments and marking them for various themes or aspects of the chance encounter. For instance, themes are coded in Figure 1 in subscript font and the underlined text marks the specific search query. Since the blogger emphasises the unexpectedness of her findings and marvels her perceived fortunes, this account meets the other two criteria as well.

A total of fifty-six accounts from the returned results met all three inclusion criteria. These accounts, returned as a result of sixteen (see Table 1) of the original forty-four queries, constitute the data used for the analyses. The complete data set will be made available on the project website ( Language and Information Technology Research Lab Projects 2011). The selected accounts of chance encounters were imported into Microsoft Access for further annotation and analysis.

| No. | Query Text | Number of Blogs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | "accidentally found" | 1 |

| 2 | "discovered ** by chance" "searching for" | 3 |

| 3 | "found *** by accident" | 6 |

| 4 | "found *** while looking" | 6 |

| 5 | "found ** by accident" | 2 |

| 6 | "found out *** by chance" "looking for" | 3 |

| 7 | "found some ** by accident" | 1 |

| 8 | "I found * when I wasn't looking" | 4 |

| 9 | "I was looking for * but I found" | 5 |

| 10 | "looking for ** but found" | 2 |

| 11 | "looking for *** but found" | 4 |

| 12 | "looking for ** but discovered" | 2 |

| 13 | "searching *** but found" | 2 |

| 14 | "stumbled across ** by accident" "searching for" | 8 |

| 15 | "wasn't looking ** when I found" | 6 |

| 16 | "wasn't looking for ** but found" | 1 |

| Total: | 56 |

Even though our data collection took place in the online environment, the descriptions of chance encounters may have taken place either in online of offline environments. Among the selected accounts, twenty-four described chance encounters in the online environment and thirty-two described chance encounters in the offline environment. Each account involved the description of a chance encounter, typically one that occurred in the process of searching for (or doing) something unrelated. The presence of a chance encounter was a criterion for the selection of an anecdote, and we are therefore limited in our ability to explore the relationship between everyday serendipity and the experience of chance. We note that chance is defined subjectively: that is, we rely on the encounterers themselves to define what constitutes a chance or accidental encounter. Interestingly, chance is experienced differently in online and offline environments. In the online environment, bloggers often described searching for information and being surprised when they encountered something useful. Although in these cases what is found is often closely related to (if not synonymous with) the original object of the search, the encounter is attributed to chance, possibly because searchers do not feel a sense of control over the search process. The chance encounter occurs differently offline, where the experience of chance often reflects finding something relevant while engaged in a different activity, finding something in an unexpected location, or finding something that comes from an unexpected source. These varieties of chance are interesting, and merit further exploration; given the nature of our data selection process, however, the current dataset is not sufficient to support a more detailed analysis.

We employed a grounded theory approach to data analysis following the procedures and canons outlined by Corbin and Strauss (1990). Grounded theory was identified as the most appropriate analytic strategy for the present study because it allows for the development of the coding scheme to be informed both by existing theoretical models and by the data itself. This gives the researcher maximum flexibility to draw from the knowledge already available in the field while at the same time remaining open to new discoveries emerging from the dataset. Our aim with this approach was to discover regularities across collected accounts of chance encounters by identifying and categorizing facets of serendipity and exploring their inter-connections.

For Corbin and Strauss (1990) it is central that every time an incident is identified, 'it should be compared against other incidents for similarities and differences', which is referred to as the method of constant comparisons. One strength of this procedure is that through constant comparisons any kind of bias can be prevented, as concepts and codes are constantly being challenged with new data. Corbin and Strauss further argue that these comparisons

help to achieve greater precision (the grouping of like and only like phenomena) and consistency (always grouping like with like). Precision is increased when comparison leads to subdivision of an original concept, resulting in two different concepts or variations on the first (Corbin and Strauss 1990: 9).

Following Cohen and Crabtree (2006), our data analysis consisted of three types of coding. The first was open coding, where data were grouped into larger categories and then reviewed for the purpose of assigning codes. The second type of coding was axial coding and consisted of grouping categories and describing these as larger themes. Finally, we employed selective coding, wherein we re-organised categories and integrated themes in such a way that it provided an over-arching framework of serendipity. Moreover, we went through iterative cycles of data collection and analysis, which is central to identifying new codes and themes as well refining the interconnections between concepts and themes (Corbin and Strauss 1990: 9).

We used the key concepts identified in the literature review as a guideline for coding, allowing also for the emergence of other important concepts from the data. Thus, our goal was to examine each account for the role and description of: a) prepared mind; b) noticing; and c) fortuitous outcome. In addition, we examined the accounts for other frequently occurring characteristics. Two researchers (first and third authors) created extensive free-form memos describing the nature of each aspect within the account and the interrelationship of the different aspects.

Charmaz (2006) advocates for the use of free-form memos as a means to enrich the data and explore the links between concepts and themes. The two coders wrote memos independently and then used them as an additional means to identify differences in the coding process. The resulting memos were aggregated, cross-referenced, and brought together into categories. The free-form notes were examined for patterns and regularities, and articulated in findings as a coherent understanding of the phenomenon of everyday serendipity in chance encounters. Each facet is defined, explained, and extensively exemplified in the results.

The Microsoft Access database served both as a data collection tool and a coding tool. Each recorded naturally occurring account in the database was assigned a unique identification number with which its annotations were conveniently linked, accessed, and queried for patterns.

The results describe a set of emergent categories or facets that have been identified on the basis of the grounded theory approach and a review of the literature. Each facet is described in detail and examples are provided. Key to our results is the establishment of linkages between facets with the aim of obtaining a better understanding of the entire process of a chance encounter as it unfolds.

The prepared mind is critical to the experience of serendipity. In our examinations of accounts of everyday chance encountering, two types of preparedness emerge. The first is a prior concern or problem and the second is previous experience or expertise. These aspects of prepared mind provide a fertile ground for everyday serendipity, affecting the ability to notice potentially relevant information and to make sense of the information in relation to prior problems, needs, or concerns.

In previous research (e.g., Erdelez 2004), the prior concern has been constructed as a pre-existing background problem that results in an information need. In our data, prior concerns included information needs, but also encompassed a wider range of needs such as for physical items or abstract items (e.g., a solution to a technical problem). Examples 2-5 demonstrate the items mentioned by bloggers ranging from magazines to a restaurant, from an alternative hotel option to a new job. Although bloggers sometimes explicitly identified the prior need in their accounts, in many cases it could only be inferred from their discussion, typically from the identification of the activity they are engaged in at the time of the serendipitous encounter.

Example 2:

And I also wanted to shout out to another amazing new found thing...Stack Magazines While looking for other independent magazines, I came across Stack Magazines and was delighted to see such a great thing. I'll be getting my subscription soon. (ID=13)

Example 3:

I found Tara Humata Mexican Grill while looking for other restaurants. I had missed a turn, was tired and saw this restaurant in a strip mall just off Windward Parkway (exit 11 off 400). It looked good, I was hungry, so I checked it out. It's very pretty on the outside. (ID=14)

Example 4:

I've been to Terresini 3 times now. We found hotel Florio by accident. Initially we booked Hotel Azzolini and walked out with disgust even though they had us on a no cancellation contract we let them keep the money. We were delighted to find this Hotel Florio just 200 meters further along the road. (ID=23)

Example 5:

That starting role as Algernon started things for Dickey. He went on to get his education degree from Missouri Southern, then moved to Florida to teach. Eventually, the McDonald County High School graduate came home. He landed a job at KODE-TV, becoming the first director for 'Good Morning Four States' with Bob Phillips and Vicki Kennedy as the first anchors. Working with the station, he helped train high school interns and realized how much he missed teaching. Dickey went on to get his master's degree at Missouri State, while working at Carthage High School, where he taught for six years. He approached Crowder looking for an adjunct job, but discovered the theatre instructor was leaving and applied for that job. 'I really enjoy teaching,' Dickey said. 'And I really enjoy working with students and I really enjoy being at Crowder because being at Crowder is like my second chance. (ID=25)

The prior concern in these cases seems to constitute a 'frame' into which the observation is placed. In many cases, the observation exactly satisfies the prior concern: a new position for a job seeker (Example 5, ID=25), or a restaurant for someone who is hungry (Example 3, ID=14). Sometimes, however, the observation offers a critical contribution to a prior concern, exemplified here by making a connection between an ancestor's and the mother-in-law's family name:

Example 6:

We moved into our current house four years ago. It was much bigger than our old house, and so had a lot of extra space to fill. ... I had one small hallway that especially cried out for something different. I decided to find vintage postcards of places that my ancestors (or my husband's) had lived. I already had a few, and I searched eBay to find more. The one above was one of my favorites. It shows the old high school in Plymouth, Wisconsin, where my mother-in-law's family has lived for generations. I bought it for $6.99. The listing said it was postmarked 1910, but it didn't say what else was on the back.

A week or so went by, and the postcard arrived in the mail. I ripped open the envelope, admired the vintage cheerleader, and then turned it over. ... This is what I saw:

Could we arrange a game down there with the Waldo High School or second team, Friday night. We would guarantee you a return game through our principal—we would want 4.00 and will give you the same when you come up. Answer on the next train as we want a game for Friday.

Le Roy LaBudde–Ass't Mgr. Plymouth High School B. B. Plymouth Wis.

LeRoy LaBudde sent the postcard. LaBudde is my mother-in-law's family's name. A quick search revealed that LeRoy was a collateral ancestor of hers. Nearly 100 years after one of her relatives mailed this postcard, I'd bought it on eBay without having a clue who it was from. What are the odds? Freaky stuff like that happens all the time in genealogy. It's pretty cool. (ID=106)

In many cases the prior need is both conscious and explicit (looking for independent magazines, Example 2, ID=13, or looking for a new hotel, Example 4, ID=23). It is possible, however, that the encountering of relevant information, people, or objects can trigger awareness of a previously unacknowledged or forgotten need. Thus, a shopper finds knee-high boots while looking for ankle boots; she is still seeking the ankle boots, but the knee-high boots appear to fill a hitherto unrecognised gap in her wardrobe:

Example 7:

There are usually quite a bit of women there ravaging the sale racks. I was actually shoved to the side as a woman tried to get to the Coach purses. Crazy shit. I finished getting most of the things I needed to buy for myself and for others. The last thing that I still want is a pair of ankle boots. I was looking for them, but I found a good pair of knee-high boots instead that I love and can't wait to wear soon.' (ID=22)

Interestingly, our data include one example where there is no identifiable prior need. In Example 8, ID=129 Serge finds himself trapped in a broken elevator. This leads to a conversation with an elderly woman who turns out to be the widow of a famous director, and in the course of the conversation Serge comes to realise that she has previously unknown footage related to her husband's work. Serge later uses this footage in the creation of a documentary, apparently arising from the encounter itself:

Example 8:

There are usually quite a bit of women there ravaging the sale racks. I was actually shoved to the side as a woman tried to get to the Coach purses. Crazy shit. I finished getting most of the things I needed to buy for myself and for others. The last thing that I still want is a pair of ankle boots. I was looking for them, but I found a good pair of knee-high boots instead that I love and can't wait to wear soon. (ID=129)

In many of the accounts we analysed, it was evident that previous experience or expertise contributed to the ability to leverage a chance encounter to achieve a fortuitous outcome. Expertise was made obvious in a variety of ways, including explicit identification of experience or qualifications, stated or implied interest in the topic, and insights based on previous experiences (e.g., prior visits to a town where a hotel is being sought). When examining serendipity in the context of everyday life, prepared mind may not require formal training or background knowledge – just awareness is sufficient. We found that simply having an interest in a topic (e.g., music, cars, technology), an object (e.g., shoes, cars), or activity (e.g., shopping) provided sufficient previous experience to provide a person with a discriminatory ability to notice and understand the usefulness of the information, topic, or object encountered in relation to the prior concern. This may be in contrast to serendipity as experienced in scientific discoveries, where a certain level of acquired and explicit expertise (including a strong background in the area of study) needs to be acquired to make a serendipitous discovery. In the single case in the data where a prior need cannot be identified (see the discussion of Example 8, ID=129, above), background knowledge apparently serves to prompt a new task (creating a documentary).

In our dataset of blog accounts, previous experience or expertise is often not explicitly identified, but rather is evident in (and inferable from) clues that are present in the account itself. Thus, for example, previous experience is signaled by the use of jargon and acronyms that could only be known by someone with knowledge of the topic:

Example 9:

I know I'd probably miss shifts and such and a converter is sweet (so I've heard) but I really REALLY wanted an M6 when I was looking for WS6's, but I found a very low milage TA ( with an after-market ram air hood ) that was an auto for what I thought was a great price (99 TA with 18,720 miles for 15k in awesome shape, tinted windows and ram air hood). I've thought about selling mine, but I love this car but I really really wish I would have waited and found an 02 NBM WS6 M6... (ID=19)

In some cases, bloggers refer to their prior experience to make sense of the information, object, or person found. This may take the form of an explicit reference to previous experience (e.g., 'I've been to Terresini 3 times now...' Example 4, ID=23); alternatively, the blogger sometimes supplies descriptions of the context that are clearly drawn from prior experience (e.g., 'There are usually quite a bit of women there ravaging the sale racks...' in Example 7, ID=22).

The act of noticing is central to serendipity, requiring attending to the object, information, or person that is encountered by chance. Often, noticing triggers a change of task or focus. Example 10, ID=124 shows a woman driving on a road (primary task) when she notices someone cutting a hedge. This observation triggers a new set of activities: to stop her car and investigate if it is indeed bittersweet (a plant she had been looking for) that is being cut.

Example 10:

Well, I finally found some Bittersweet... totally by accident. I was driving to a nearby town, when I spotted an older gentleman on the side of the road with some clippers in hand. I thought... no way, he couldn't possibly be cutting some Bittersweet... But I had to know... So, nosey me and a being the desperate woman that I was for some... I turned the car around and pulled up next to him and said 'You wouldn't happen to be cutting some Bittersweet would you?' and I couldn't believe it when he said he was! Hidden in some overgrown weeds, there it was! (ID= 124)

In our dataset, people do not describe the details of the shift in attention (a perceptual process), but it can often be inferred from their acknowledgement of a chance encounter in the context of a primary activity to which the encounter is not relevant (see Example 11):

Example 11:

I am so, so pleased to have stumbled upon this! :) Earlier this month, I watched "WALL-E" on DVD for the very first time, and it just charmed the pants off me. :) Since then, I had casually searched the grid for an EVE (Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator) avatar....and I found it! What's funny was, I found it when I wasn't looking for it, which was a bit of a "DUH!" moment for me, considering I located the avatar in the Greenies sim!' (ID=34)

In online environments, noticing is often linked to searching or browsing on the Internet. One of the typical examples of online chance encountering is finding one type of information while searching for another. This describes yet again a shift in attention from a primary task toward the discovery. Bloggers often leave an acknowledgement on web sites in the form of a note that expresses gratitude for the finding:

Example 12:

Hi thanks for an perceptive post, I actually found your blog by mistake while looking on Google for something else closely related, in any event before i ramble on too much i would just like to say how much I loved your post, I have bookmarked your site and also taken your RSS feed, Again thank you very much for the post keep up the great work. (ID=10)

In the offline context, noticing is often linked to perceptual cues in the environment: seeing something or getting something that piques one's interest, like a signature on a postcard (Example 6, ID=106). In addition, various triggers can bring awareness of a prior concern to the foreground.

In sum, in the accounts produced by bloggers, noticing can be inferred from the description of a primary activity during which the finding is encountered. The act of noticing seems to differ in online and offline environments. In the online environment, bloggers typically describe a primary involvement in searching for something else and the relevant information, object, topic, or person is encountered while carrying out this primary activity. In the offline environment, attention is shifted to the encountered discovery as a result of perceptual cues in the environment: for example, seeing something unexpected and meaningful that piques one's interest or triggers a connection.

The fortuitous outcome of a chance encounter provides unexpected benefits that are not linked to the primary activity in which bloggers were involved. We found that the descriptions of the fortuitous outcome ranged in detail and specificity across accounts. For some bloggers, a description of the value of the finding was an important element in the retelling of the chance encounter. In some accounts, however, the fortuitous outcome had to be inferred on the basis of the description of the find (e.g., by noting, as in Example 13 (ID=12), that the found work was interesting, and therefore valuable to the blogger: 'some interesting work by Steph Von Reiswitz') or through interpretation of positive emotional expressions associated with the encountered object (e.g., through the use of emoticons as in Example 11 when the blogger found the avatar, ID=34 : 'I am so, so pleased to have stumbled upon this! :)' ).

Example 13:

Some interesting work by Steph Von Reiswitz that i found here Le Gun while looking for agents and representatives for freelance illustrators... (ID=12)

In these accounts, the fortuitous outcome involved an evaluation of the encountered information, object, topic, or person in the context of the prepared mind: that is, the prepared mind provided the backdrop to make sense of the find and understand its value. Without a specific prior concern, problem, or interest, the encountered information is irrelevant and would not be noticed. Example 10, ID=124 illustrates how the noticing of bittersweet is a fortuitous outcome precisely because the women driver had been looking for this plant.

In other cases, the relationship between prepared mind and outcome is more complex. For Serge Bromberg (Example 8, ID=129), the fortuitous outcome is a 'slickly produced documentary' that relies on 'choice cuts' from footage that was discovered as a result of an accidental encounter. Serge had not been looking for the footage, nor had he been considering producing the documentary, but as a result of his knowledge and background he was able to recognise the value and importance of the discovery when he encountered it.

Outcomes are not always simple, as there may be layered outcomes that result from a discovery. In the case of Serge Bromberg (Example 8, ID=129) we have identified the production of the documentary as the fortuitous outcome; another (and more direct) outcome of the chance encounter is the discovery of the footage that is used in the film. In Example 14, ID=127 the chance encounterer discovers a hitherto unknown poet (Lin Zhao). The immediate outcome is the knowledge 'that in Mao's China there was this kind of people who would fight against the Communist Party, literally with blood'. Later on, the encounterer loses her job as a result of her interest in and research about this poet, both of which are triggered by the chance encounter.

Example 14:

SR: How did you discover Lin Zhao?

HJ: Actually I discovered her story by chance. One day a few friends and I were hanging out. One of them said his parents were Lin Zhao's classmates. I asked who Lin Zhao was. He told me that Lin Zhao was a student at Beijing University in the 1950s. Because of some poems, she was arrested and put in gaol. In gaol she continued writing. She did not have any ink, so she wrote many things with her blood. In the end, she was executed.

His words were simple but very shocking to me. I had never heard this kind of story: that one was arrested for writing poetry and killed for writing books with blood. I never thought that in Mao's China there was this kind of people who would fight against the Communist Party, literally with blood. I thought that writing with blood could only write a few characters, but I was told that Lin Zhao wrote thousands and thousands characters with blood.

This story was so shocking that I began to collect information and materials about Lin Zhao. I wanted to know her. By then I was working at the Centre for Pictures of Xinhua News Agency. I had worked there less than three years, shooting those short films about migrant workers. After I began to conduct research about Lin Zhao, one day my boss in Xinhua News Agency talked to me and told me that I could not work there anymore. He was very serious and said, 'What you are doing, you know best. We do not want to know. You have two choices. One is to be fired from your job; the other is to resign by yourself.' I thought it would be terrible to be fired, so I chose to resign. They did not tell me why, but I know clearly: I was doing research on Lin Zhao. They also told me that they did like me very much because I was one of the major hands at the Centre, but they could not allow me to continue working there due to pressure from above. Who is above Xinhua News Agency? I understand that must be The Bureau of Public Safety. (ID=127)

In our analysis, we have relied as much as possible on evidence provided in the account to identify the fortuitous outcome that is most relevant to the encounterer. In many cases, the fortuitous outcome is flagged right at the outset of the account (e.g., 'Well, I finally found some Bittersweet' or 'Hi, thanks for a perceptive post' or 'Woah! The Nike Air Tech Challenge Hybrid!!!'). In other cases, the account builds toward the fortuitous outcome in a more traditional narrative. Thus, in Example 6 the blogger tells a linear story culminating in a description of the positive result: 'Nearly 100 years after one of her relatives mailed this postcard, I'd bought it on eBay without having a clue who it was from. What are the odds? Freaky stuff like that happens all the time in genealogy. It's pretty cool.' In those cases where the account does not clearly signal the outcome from the perspective of the encounterer, we have focused on the outcome most closely related (usually temporally) to the discovery. Thus, in the case of the discovery of the unknown poet (see above), we have constructed the resulting knowledge as the outcome of the chance encounter.

There is a broad range of fortuitous outcomes described in the data set. These outcomes can be classified into three general categories according to the type of benefit experienced, ranging from the very abstract to the very concrete. We describe each next and provide examples to show how they differ.

1. Perceived value: The fortuitous outcome does not always entail a change in action; it can simply consist of an abstract benefit. In these instances, the value of the discovery can be inferred from people's descriptions of how they reacted to the discovery when they first discovered it. Examples of how the reaction of the discovery is described in the blogs include positive emotionality (e.g., happy ending, memories of past experiences), new insight into an issue, new information on a topic, and confirmation of an existing perspective. Positive emotionality was sometimes expressed in the form of simple and short statements of gratitude that could be cliché thank-you notes for visiting a site (Example 1, ID=1). Other statements were more elaborate in the extent of their gratitude and encouragement (Example 12, ID=10).

Another alternative in acknowledging perceived value in the blogs was the positive experience of having encountered the discovery: that is, the mere fact of noticing, finding, or seeing is experienced as rewarding. For instance, in Example 15, the blogger expresses his delight of seeing the ruins and regrets not being able to have another chance to see it:

Example 15:

Wat Rang: I have only seen this temple once. It is located on somebody's private property, so viewing it is difficult. I stumbled across it only by accident. I was kayaking during flood season and got semi-lost. I could see part of this ruin from a distance, but forgot to bring my camera that day. It is too bad because I may never get a second chance. I can't recall much worth seeing anyway. It is in the vicinity of Wat Kwid and Wat Pra Dong, which are also heavily eroded. This area near Klong Sa Bua seems to flood often. (ID=113)

In these instances, the act of seeing, finding, or noticing is the reward. This finding suggests that becoming a chance encounterer, someone who by chance found something relevant, important, or meaningful is a positive experience in and of itself.

2. Solution to a prior problem or concern: These kinds of fortuitous outcomes are directly linked to an existing prior concern or problem, and less so with an existing interest for a topic or activity. It is important to note that in the context of chance encounters, the prior concern or problem is usually in the background. It is an underlying issue that has not been resolved, but continues to be of relevance to the individual. The fortuitous outcome then arises from the fact that the solution to a problem or resolution of a concern is found without much effort (or any effort) on the part of the individual. Individuals basically stumble across the discovery, and it is this unexpectedness that leads to experiencing the finding of the solution as chance. This is exemplified in Example 10 (ID=124), where the problem was finding bittersweet. The chance encounterer was not looking for bittersweet when she came across it. The problem was in the background while she was doing something unrelated (driving). This shows how the solution to an existing problem presents itself through the chance encounter with an object, person, or piece of information.

3. Action plan or action taken based on the discovery: The fortuitous outcome can consist also of new actions. In these cases, the consequences can lead to life-changing events or unexpected turns. In Example 14 (ID=127), the blogger's life changes in a number of ways as a result of her accidental discovery of Lin Zhao, a dissident of the Communist Party. Learning about the poet piqued her interest and she started to research her life story. This interest took her on a new journey as she was forced to resign from her current position.

In other situations consequent actions carry a lesser impact; nonetheless, these stories articulate a concrete action plan, such as subscribing to a new magazine (Example 2, ID=13) or visiting a restaurant (Example 3, ID=14). This shows how the fortuitous outcome can consist of a new action or a new action plan.

In our analysis of the accounts, it became evident that we needed to consider what is accidentally encountered: we characterise this as the find. The types of find represented in our dataset of everyday chance encounters varied by type, and included: 1) items or places (e.g., a pair of boots in Example 7), 2) ideas (e.g., a perceptive post in Example 12), 3) information (e.g., theatre instructor was leaving in Example 5), and 4) people (e.g., the widow of Clouzot in Example 8), or some combination of these.

Obviously, there is some overlap between these categories. Ideas, for example, are often linked to people who generate them. Discovering people and their life stories could be a find in itself, or could lead to a new idea or to the artifacts associated with the people, as in Example 8, ID=129.

Online items (such as a program that performs a certain function) are also ultimately an implementation of someone's idea. A relevant web-site or a link (as in Example 16 below), could be conceptualised as a physical object, information, or an idea, depending on the writer's emphasis.

Example 16:

I stumbled across this site by accident, my freakishly old computer is slow and sometimes the link you click, isn't the one you were trying for... (ID=120)

The find is clearly articulated in the chance encounter accounts, typically stated towards the very beginning or the very end of the story, often with some elaboration regarding its perceived value and the circumstances surrounding the chance encounter with the find.

We attempted to categorise each account according to the nature of the find (item, idea, information, or person). In making these classifications, we were guided by the story itself and the conceptualization of the author [thus, for Example 8 above the find is characterised as an object (the cans of footage), rather than a person (the widow of Clouzot)]. Among the finds in the dataset, there were thirty-six items, ten ideas, six information pieces and four people (see Table 2). Out of fifty-six items, thirty-two were artifacts in the offline environment (like a pair of high heel shoes found in a store) and twenty-four were found in the online environment (like a perceptive post).

| Context: type of find | Online environment, number of accounts |

% | Offline environment, number of accounts |

% | Total, number of accounts |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idea | 6 | 25% | 4 | 13% | 10 | 18% |

| Information | 4 | 17% | 2 | 6% | 6 | 11% |

| Item | 12 | 50% | 24 | 75% | 36 | 64% |

| Person | 2 | 8% | 2 | 6% | 4 | 7% |

| Total, no. of accounts |

24 | 100% | 32 | 100% | 56 | 100% |

Research on everyday serendipity has focused on the encountering of information (e.g., Erdelez 1997;; Foster and Ford 2003; Toms and McCay-Peet 2009; Williamson 1998), while examples in the scientific literature tend to describe the chance encountering (or noting) of observations such as the death of mold in a petri dish or the 'floppiness' of rabbit ears (e.g., Barber and Fox 1958; Rosenman 2002). In these accounts of everyday encountering, the focus of the encounter takes a variety of forms, as objects, information, ideas, and/or people.

The accounts selected for inclusion in the dataset all involve chance encounters. In many of the accounts, the bloggers highlighted the experience of surprise related to these chance encounters, either by explicitly noting the surprise (Example 2), or by interjections such as 'Woah!' (Example 11, ID=34 and Example 17, ID=114).

In some cases, bloggers expressed surprise at the very existence of the find, as in the following.

Example 17:

Woah! The Nike Air Tech Challenge Hybrid?!?! WTF? I have no idea how this one got past me but HOLY $HIT! I think my head just exploded! I guess news of this new sneaker from Nike dropped all the way back in September of 2008. Whoops. I actually stumbled across this shoe by accident while searching for some other kicks. After I calmed down and figured out what the hell was going on, I did a little more digging. They were originally set to drop in Summer 2009 but you can actually buy them already at PickYourShoes.com. I don't know if that is a pre-order or not but it is at least a sign that they are on their way to stores very soon.' (ID=114)

In other cases it is the location, rather than the existence, of the find that is surprising. In these accounts, the blogger recounts stumbling across the find in an unexpected context or place, as in the following account:

Example 18:

How I found out about the Loy Krathong festival was by pure chance. I was walking around Bangkok far away from where I live to look for cool things to take pictures of hoping I would run into the Chao Phraya River when the inevitable happened.

On a Saturday night I got lost walking aimlessly around an area of Bangkok where I had never been before. It was around 7pm and completely dark around the area with wide streets of several lanes. I saw some canals but I figured I was nowhere near the river so I decided to get a taxi. I found a taxi but as usual the driver could barely understand my Thai or English. He finally understood I wanted to go to the Chao Phraya River and he seemed pretty excited to take me there. I had no idea there was any kind of festival going on but when we finally drove over the bridge I saw the following...

I was instantly excited. I was figuring that I would be taking pictures of the same Bangkok skyline that I had many times before but now I had a bunch of cool boats and other stuff. The taxi driver let me off across the Rama VIII bridge on the bottom under the bridge where there was a large festival with tents set up with various souvenirs, games and food. (ID=131)

Finally, surprise often resulted from making a connection related to the find. 'What are the odds?' as the blogger puts it in Example 6 (ID=106), of finding a signature of the blogger's ancestor on a post-card purchased from eBay.

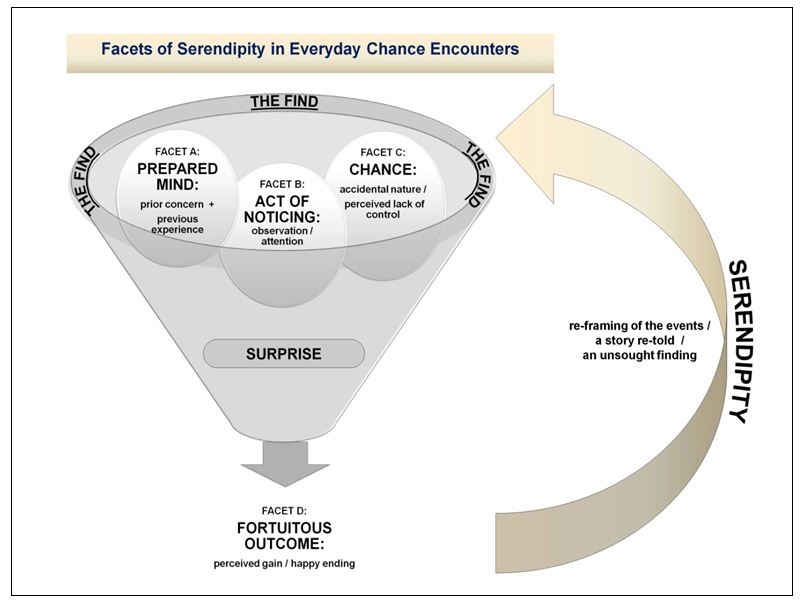

Figure 2 depicts the facets of serendipity that we observed in naturally occurring descriptions of chance encounters in blogs. The model is based on the review of the literature and our examination of re-told stories of chance encounters.

The Find: Central to our model is the concept of the find: the essence of what is encountered by chance. As depicted in Figure 2, the find functions as a funnel in bringing together all the facets of the serendipitous encounter. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the find as 'something valuable' (2011); alternatively, the find is 'a person who is discovered to be useful or interesting in some way' (2011) which also fits our understanding of this term. Serendipitous encounters by definition involve an encounter with something that has subjective value for the finder. Thus, for instance, 'a hodgepodge of things' for making vintage jewellery is a treasure to one blogger (see Figure 1 example, in Methods section).

Facet A: Prepared Mind consists of two linked components: a prior concern and previous experience. A prior concern is a pre-existing problem and previous experience refers to a personal accumulated knowledge or expertise (e.g., in making vintage broaches and bracelets in Figure 1 example) that helps to make sense of the find. Previous experience is critical to understanding the uniqueness, relevance, or importance of the find. A prior concern is also important in understanding the importance of the find. In addition a prior concern may influence noticing, making it more likely that some types of finds (those related to prior concerns) will be noticed.

Facet B: Act of Noticing. The person not only has to have a prepared mind, but needs to be able to notice the find and shift the attention from a primary activity to a clue in the environment, or a trigger in Erdelez's terms (2004). For instance, the vintage 's maker spots a sale sign (Figure 1).

Facet C: Chance. A necessary pre-condition of serendipity is the presence of chance: an accidental or unplanned encounter with the find. The chance component captures the accidental nature of the encounter and underlines the perceived lack of control, as testified in the following phrases in our example: 'stopped on a whim', 'wasn't actively looking for sales' (Figure 1).

Facet D: The Fortuitous Outcome. A chance encounter provides unexpected benefits linked to the find. The model shows that each of the descriptions, re-told as chance encounters, ends with a fortuitous outcome such as being able to do 'many 's projects' including dangling domino earrings (as on a photograph included in the original blog we use in Figure 1).

The conceptualization of the find is key to understanding serendipity because it functions as a funnel in bringing together all the facets of the serendipitous encounter: a) the find becomes relevant to a person with a prepared mind; b) it is only discovered by a person who has an ability to notice it; c) the find is what people encounter accidentally; d) it is what leads to a fortuitous outcome, and e) it is the essence of the re-telling of the story. Each of the other aspects contributes to the experience of serendipity, and they are inter-related in ways that are signaled in the accounts. Equally important to understanding serendipity is the fortuitous outcome, because it is only at the end of the story, when the fortuitous outcome has occurred, that a serendipitous encounter can be distinguished from other chance encounters of no great meaning.

Together, chance (or the perception thereof), the prepared mind, and the act of noticing provide the link between the find and the fortuitous outcome. With respect to chance, a serendipitous encounter is one that (according to the encounterer) might very well not have happened. If an encounter is fully anticipated, or directly sought, then it is not serendipitous. It is only those encounters that are out of the ordinary and unexpected that are marked as serendipitous. In the act of noticing the chance encounter is 'singled out' or brought to the attention of the encounterer. A prior concern influences this noticing, increasing the likelihood that particular information, ideas, objects, or people (that relevant to the prior concern) will actually be noticed. Previous experience helps the encounterer to make sense of the information, idea, object, or individual encountered, and also provides the critical link between the find and the fortuitous outcome.

The role of surprise in the context of accidental encounters is unclear, and worth exploring in further research. Chance seems to be a necessary but not sufficient condition for surprise, which also requires that the chance event be meaningful in some particular way. Thus, it would not surprise someone to find a relatively random selection of people at the Eiffel tower on any given day; she would, however, be surprised to encounter her brother there if she had reason to believe he was instead at home, for instance, in Canada. Conceptually, surprise must rest on the substrate of a prepared mind: surprise at the existence of the find arises only when one has prior reason to suspect the find might not exist (or at least no prior reason to believe that the find does exist), and surprise at the location of the find arises only when one has prior reason to expect the find to be located elsewhere. The relationship between noticing and surprise is more difficult to ascertain: does noticing result in surprise, or does surprise (at some pre-conscious level) prompt noticing? This latter effect is evident in lower level perceptual processes [i.e., perceptual surprise leads to noticing (see, e.g., Baldi and Itti 2010; Itti and Baldi 2009)], and it is possible that surprise linked to more complex characteristics (the unexpected location of an item, for example) could also trigger noticing. Thus, we note that surprise may be operating in two distinct ways in the context of serendipity: as a cognitive/emotional reaction to the serendipitous encounter, perhaps even constructed (or at least emphasized) in the retelling of the event; and as a trigger for an orienting or noticing response.

Our original intent was to collect naturally occurring rich descriptions of chance encounters from blogs. Our search strategies identified many accounts of chance encounters with Selective Blog Mining. Relatively few, however, included rich descriptions, and therefore the vast majority of the returned accounts were not included in the dataset. The main problem with the collected data was that participants reported only part of the story, often leaving out important details that would help elucidate the nature of everyday serendipity. In some cases, it was possible to infer the missing information (e.g., a comment that encountered information was 'interesting' could be interpreted as a positive outcome), but more information would have been beneficial. Future research needs to identify alternative sources of data that can provide 'thick' descriptions of serendipity as it occurs in everyday contexts and thereby provide further insight into the proposed model.

The study and the model of serendipity that we have developed provide insight into the facets involved in everyday chance encounters. This work, while still in its early stages, provides some suggestions for the facilitation of serendipity in online environments. Our results suggest that there may be opportunity for intervention in the act of noticing. In particular, tools could be used to increase the perceptual salience of potentially relevant information so as to increase the possibility that it might be noticed. Serendipity may also be increased if background problems or concerns are occasionally highlighted or brought to awareness, in order that relevant information, ideas, or people can be noticed. Further research should explore the effectiveness of these interventions (in the form of system design requirements) in increasing serendipitous encounters in the online environment.

A second contribution of the study is the demonstration of the strengths and weaknesses of the method of Selective Blog Mining which consists of obtaining naturally occurring descriptions of chance encounters from blogs. The data obtained through this methodology has several strengths in comparison to those obtained in controlled research settings: they are freely and publicly available online, 2) created by bloggers independently of the study, and 3) are written by self-motivated writers for an unknown audience. In addition, in comparison to the situation recall methodology, Selective Blog Mining descriptions have high validity because they show how individuals reflect upon their experiences without an explicit elicitation.

We would like to thank Pamela Saliba and Jeremy Clark for data collection and management. We also thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This study was funded in part by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Grant R3603A07 awarded to A. Quan-Haase.

Dr. Victoria Rubin is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Information and Media Studies and the Principal Investigator of the Language and Information Technologies Research Lab at the University of Western Ontario. She received her Ph.D. in Information Science and Technology in 2006, her M.A. in Linguistics in 1997 from Syracuse University, NY, USA, and a B.A. English, French, and Interpretation from Kharkov State University, Ukraine in 1993. Dr. Rubin research interests are in information organization and information technology. She specializes in information retrieval and natural language processing techniques that enable analyses of texts to identify, extract and organize structured knowledge. She can be contacted at vrubin@uwo.ca.

Dr. Jacquelyn Burkell is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Information and Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario. She holds an M.A. and a Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology from the University of Western Ontario. Her research interests focus on the impact of technology in everyday life, and the use of information in the online context. Much of her recent research has examined privacy and anonymity in the online context, as a collaborative researcher in 'On the Identity Trail', a SSHRC-funded research project. She can be contacted at: jburkell@uwo.ca.

Dr. Anabel Quan Haase is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Information and Media Studies and the Department of Sociology, University of Western Ontario. She obtained her Diplom (M.Sc.) in Psychology at the Humboldt University in Berlin and her Ph.D. at the iSchool, University of Toronto. She currently holds a Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada grant to study the use and social implications of information and communications technology in communities, organizations and everyday life. She is the author of Information Brokering in the High-Tech Industry. She can be contacted at: aquan@uwo.ca.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

© the authors, 2011.

Last updated: 14 August, 2011 |