vol. 16 no. 3, September, 2011

|

vol. 16 no. 3, September, 2011 |

||||

The workshop was conducted during a project meeting for SerenA—Chance Encounters in the Space of Ideas, a £1.87million UK Research Council funded project aimed at understanding the role that serendipity plays in research and innovation in the digital economy. Aware that serendipity is a particularly slippery concept, this workshop was envisaged as a starting point for better understanding this phenomenon. Discussions from the workshop were intended to support the project team’s evolving understanding of the nature of serendipity in order, later in the project, to inform the design of technology to facilitate serendipitous interactions.

The interdisciplinary SerenA project team split themselves into three groups of four people, each from different institutions and with different research interests ranging from human-computer interaction and artificial intelligence to art and musicology. Each group was asked to generate examples of experiences they considered to be serendipitous from either their work or everyday lives. As the aim of the workshop was to examine what serendipity meant to them, no definition of the term was provided and the workshop was conducted early in the project meeting to avoid bias.

The groups were asked to write their examples of serendipity on large post-it notes and, with the aid of discussion, to classify them as yes (i.e., definitely serendipitous), maybe (possibly serendipitous) or no (on reflection, not serendipitous). The groups were also asked to note any patterns between examples that might help to understand the nature of the phenomenon. One of the groups is pictured in figure 1.

The examples generated by the groups were varied. Those that were labelled as yes included chance scientific discoveries, such as X-rays and penicillin and general library and Web-related examples such as coming across an interesting book when looking for another one and noticing a particular search result was relevant for satisfying a different information need entirely. Some of the yes examples were less general. For example, one group member sent an e-mail to a friend mentioning an upcoming trip to the USA. The reply mentioned it was easy to apply for an Electronic Travel Authorisation online and this made the group member aware of the need to do so at least seventy-two hours before travelling. Another non-general example included a member of the team thinking that line drawing software might be useful for their work and then, the next day, meeting a programmer who had developed a line drawing package and was able to give a copy to the team member.

Examples labelled as maybe were also varied and included bumping into the same person at different airports on three occasions (leading to enjoyable flights and continued contact), thinking of someone and bumping into them shortly afterwards and meeting someone and then discovering close mutual interests. Another team member gave the maybe example of making friends with a mother from school who was house-hunting and mentioning a house was for sale on her street. This led to the mother buying the house and the two families becoming good friends. Figure 2 illustrates two other examples labelled as maybe.

There were only two examples which, upon reflection, team members classed as no (i.e., not serendipitous). These included a team member discovering through university big brother-type checking procedures that they had not been named on a research proposal when they should have been and a team member finishing their PhD at the time when a member of academic staff in their department was leaving, being asked to cover temporarily and, eventually, being offered the job permanently.

The team highlighted that whilst some of their examples have had a significant impact on the world (such as the discovery of x-rays and penicillin), others (such as unexpectedly discovering an interesting book en route to one already sought) are more mundane, but still an important avenue of research for better understanding serendipity and designing interactive systems to facilitate it.

When asked to discuss patterns they had identified in their examples, several team members described the unexpected nature of serendipity. It was proposed that it may be possible to experience serendipity whilst seeking to address a clear, specified goal (by making an unexpected connection related to another, unrelated goal). It was also suggested that it may be possible to experience serendipity whilst seeking to address a vague, poorly-specified goal or with no specific goal in mind at all (consider browsing a physical library or surfing the Web with no particular aim other than to find interesting sites). Regardless of the level of goal-directedness, there was a common consensus that specific serendipitous outcomes were not actively sought (even during creative activities where inspiration may be a desired outcome). Serendipitous information acquisition was therefore considered to be something we are not looking for and did not expect to find.

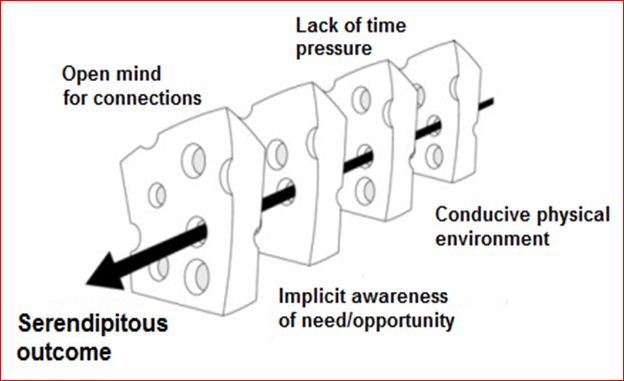

It was also proposed that for serendipitous outcomes to occur, both the internal and external conditions must be right. Internal conditions might include a prepared mind that is ready to make serendipitous connections, an implicit awareness of a need or opportunity for making the connections and a lack of time pressure that might otherwise hinder the making of these connections. External conditions might include a conducive physical environment (for example, a team member mentioned making serendipitous connections when washing up). Other team members mentioned acquiring information serendipitously in physical environments such as bookstores and libraries. It is also possible to extend the notion of an external environment that is conducive to serendipity to electronic environments. It might be hypothesised that users are more likely to make serendipitous discoveries when browsing YouTube with no goal other than to find entertaining video clips, for example, than when searching for a particular video clip.

The internal and external conditions discussed above are presented as part of the Swiss cheese model of serendipity in Figure 3, which was proposed by one of the team members as a potential model for the phenomenon. In its original human error context, the model suggests that accidents can occur when it is possible for the arrow to penetrate through all the layers of the Swiss cheese. In a serendipity context, the model suggests that serendipitous outcomes might only occur given the correct internal and external conditions.

The team also discussed the potential presence of a catalyst or stimulus for serendipitous outcomes. These catalysts/stimuli may be physical or mental in nature and might simply involve noticing a potentially valuable and unexpected connection between two previously unconnected thoughts, ideas or pieces of information. This might occur through a physical event, such as bumping into an acquaintance in the street or through a mental association based on similarity, metaphor, analogy etc. Sometimes it may not be possible to identify the catalyst or stimulus for a serendipitous outcome; it may be possible for something to click in one’s mind and a serendipitous connection to be made without a conscious awareness of how the connection came about. This was discussed by the team in the context of black box vs. open box, where for certain people and in certain situations, a serendipitous connection might seem to have been made by magic, without conscious awareness (black box) whilst for other people and in other situations, it may be possible to specify exactly how the connection had been made (open box).

It was also proposed that there must be a clear, positive outcome in order for an event to be classed as serendipitous. This might involve there being a change in a person’s state of knowledge or awareness as a result of the event (i.e., a change in the head) and possibly, although by no means always, a change in the physical environment (a change in the world), where the world might be slightly different as a result of the serendipitous event than it would have been had it not happened. In order for the outcome of an serendipitous event to be deemed as positive, it also follows that the serendipitous event itself must be recognised and mentally labelled as serendipitous by the person experiencing it.

The temporal aspects of serendipity were also discussed. Whilst it is possible to realise immediately that a serendipitous event has happened, it was proposed that there may be a lag ranging from seconds to years for someone to realise that serendipity has occurred (i.e. a lag in making the serendipitous connection). Closely related to this is the notion of value; it was proposed that it is necessary to recognise the potential positive value of a serendipitous event in order for it to be classed as truly serendipitous. It may also be possible for someone not to realise the value of a serendipitous event until later. Someone might even experience a potentially serendipitous event without ever mentally labelling it as serendipitous and/or without ever recognising the positive value of the event.

The discussions arising from this workshop were a useful first step for understanding the nature of serendipity. These discussions were also useful for providing the project team with a reference tool for looking back at our initial understanding of the phenomenon at the end of the three-year project and identifying how and why our understanding has changed during the course of the project.

Next steps include a series of empirical studies across disciplines aimed at creating a richer understanding of this phenomenon, focusing in particular on coming across information serendipitously. These studies will initially involve exploratory, semi-structured interviews aimed at pinning down important concepts and ideas surrounding the nature of this type of information acquisition.

This work was supported by EPSRC Project EP/H042741/1.

Stephann Makri is a Research Associate at University College London Interaction

Centre. His current work involves understanding how researchers come

across information serendipitously in their work and everyday lives

and using this understanding to inform the design of ubiquitous

computing environments as part of a £1.87m UK Research

Council-funded project: SerenA: Chance Encounters in the Space of

Ideas. He can be contacted at s.makri@ucl.ac.uk.

Ann Blandford is Professor of Human-Computer

Interaction at University College London Interaction Centre. She is

co-investigator on the SerenA project and can be contacted at a.blandford@ucl.ac.uk.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

© the authors, 2011.

Last updated: 19 August, 2011 |

|