Understanding information behaviour in palliative care: arguing for exploring diverse and multiple overlapping contexts

Ina Fourie

Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

Introduction

Palliative care is associated with life-threatening diseases such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, renal failure and motor neuron disease, often adding the word advanced or metastatic in the case of cancer. Some authors associate brain injuries, cerebral strokes, heart conditions, liver failure, Alzheimer's disease, spinal cord injuries, severe lung and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and multiple sclerosis with palliative care (Pastrana et al. 2008). Palliative care is mostly associated with terminal illness, hospices (Lawton 2000) and medical cases where curative care (i.e., treatment to cure) is replaced by palliation aimed at enhancing quality of life while awaiting death (Saunders et al. 1995). An increasing number of patients and families and people working with them (also called actors, stakeholders or role players) are affected, e.g., doctors, nurses, social workers, pastors and friends. They are all affected differently, their information behaviour differs, and they may cross-influence one another's information behaviour (Friedrichsen 2002; Kirk et al. 2004). Patients' and families' frustrations with information provision and communication are often reported (Fourie 2008; Kirk et al. 2004). We continue to ask the same questions, using the same standardised measuring instruments and getting the same answers (Williamson and Manaszewicz 2002), with little evidence of improvement of information-related interventions such as patient education, information sessions, brochures and even websites or Internet portals to support patients.

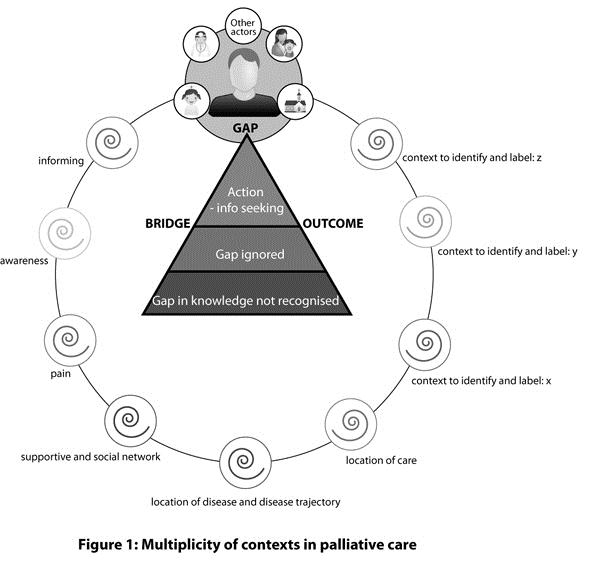

Following an extensive literature survey of information behaviour in palliative and cancer care (Fourie 2008, 2010), which is not reflected here, as well as personal observation and a preliminary survey of literature on palliative care per se, such as reports on awareness of death and dying (Glaser and Strauss 2005) and hospice care (Lawton 2000; Saunders et al. 1995), it seems timely to reconsider the demarcation of studies of information behaviour in palliative care in terms of how context is considered. Where we look, i.e., context(s), how we look, i.e., methods and style of data collection, and whom we approach, will influence what we learn and how we develop information-related interventions. Considering what patients in palliative care and their families go through in addition to information-related frustrations, it seems crucial to deepen understanding of information behaviour. This paper will argue for exploring diverse and multiple overlapping contexts faced by patients in palliative care. Against a background in which key concepts, namely palliative care, information behaviour and context, are clarified, and the status quo on information behaviour in palliative care is briefly sketched, (1) ongoing frustrations with unmet information needs; (2) the complexity of information behaviour and influencing factors; and (3) the need for information-related interventions will be discussed. To explain the proposed model (Figure 1), a few contexts are briefly described as examples. These include the contexts of informing, awareness, location of disease and disease trajectory, pain, support and social networks, and location of care. The paper represents research in progress, building on earlier work (Fourie 2008, 2010).

Clarification of concepts

Key concepts directing research are often treated as if readers would intuitively understand them or by merely accepting a frequently cited definition. Because of length constraints, this paper will not offer a detailed analysis, although the need for this is acknowledged.

Palliative care

There are different interpretations of palliative care: it is associated with a diagnosis of a life-threatening disease and the care and treatment that follow. In disease stages described as advanced, treatment can still be aimed at cure, but care is mostly based on palliation aimed only 'at the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual' (World Health Organisation). In this sense palliative care is strongly associated with hospices, terminal illness and dying.

A systematic review by Pastrana et al. (2008), analysing thirty-seven English and twenty-six German definitions, revealed no consensus on definitions of palliative care, only overlapping categories and common elements. These include the theoretical principles and goals of palliative care, such as the prevention and relief of suffering and improving quality of life; structures that are in place, such as constant service and a multidisciplinary team; the target for palliative care, such as the patient population, and timing of palliative care (e.g., when cure is no longer possible); tasks involved in palliative care, such as control of the symptoms and comprehensive care; and the expertise involved, such as specialist knowledge, skills and attitudes.

Taking the work by Pastrana et al. (2008) as point of departure, the following inter-related conditions can serve to demarcate contexts of palliative care. Referring to the context of palliative care implies one or more problems, such as diagnosis with a life-threatening disease, and various sub-issues, such as pain and symptoms that require treatment; different phases of the disease, such as the time of diagnosis, progression to a more advance stage, moving from curative care to palliation, terminal phase, days before dying; specific purposes, objectives, and goals of palliative care, which are mostly related to palliation, relieving pain and aiming for quality of life and dignity in dying; tasks associated with palliative care, such as management of symptoms and comprehensive care; processes related to palliative care, such as dying and grieving; target groups affected by palliative care, including patients, their relatives and health care workers; a multi-disciplinary team approach drawing on physicians, nurses, social workers, councillors, dieticians, etc.; specialist expertise and skills, e.g., in breaking bad news and grief counselling; a specific setting to which patients are confined e.g., hospice, cancer hospital ward or home care; elements of palliative care, such as ethics, disclosure, confidentiality, and palliative care structures, such as legislation on euthanasia and treatment policies.

Information behaviour

Information behaviour includes active information seeking (directed, undirected, purposive, problem-based, conscious efforts), passive information seeking (unconscious efforts, which may include encountering information, serendipitous discovery of information, glimpsing, information exposure), browsing, semi-directed information seeking, scanning, information foraging, information discovery, information giving, information sharing, information use, information transfer, choice of information sources, preferences for information sources and channels, information avoidance and ignoring information needs (Case 2007; Courtright 2007; Wilson 1999 - and many others). It is 'the totality of human behavior in relation to sources and channels of information' (Wilson 1999: 249).

Information behaviour includes the recognition, expression and formulation of information needs; the challenges inherent in these processes are reflected in Taylor's (1968) work on visceral needs, conscious needs, formalised needs and compromised needs, as well as Wilson's (1999) reference to dormant information needs and people being unaware of their information needs. According to Dervin (1999), information needs arise because people need to make sense of their world; it implies a gap that can be filled by something that the person who needs to make sense of something calls information. Information needs are also associated with an anomalous state of knowledge (Belkin et al. 1982). Figure 1 depicts the patient in palliative care who may experience a gap in his or her knowledge, an information need (most probably numerous information needs) (Fourie 2008; Kirk et al. 2004). A patient can recognise a gap and by actively seeking information, can try to bridge the gap between what s/he knows and what s/he needs to know to make sense of the illness and dying, deal with the pain, cope with fear, grief and many other issues (Lawton 2000; Friedrichsen 2002; Kirk et al. 2004) (The last-mentioned points to the output in Figure 1 - e.g., if information helps a patient to cope better). A patient can also fail to recognise the gap (i.e., be unaware of the information need) or decide to ignore it and take no action. The context in which patients find themselves and the people who share this context with them may influence their ability to recognise and deal with gaps in their knowledge and their efforts to make sense. Such people, as depicted in Figure 1, may include family members, nurses, doctors and religious counsellors.

Context

In spite of context often appearing in titles of studies on information behaviour, the term seems 'largely amorphous and elusive' (Courtright 2007: 277). Dervin (1997: 13) explains that, 'After an extended effort to review treatments of context, the only possible conclusion is that there is no term that is more often used, less often defined, and when defined, defined so variously as context'. The few attempts to conceptualise context in studies of information behaviour include those of Courtright (2007), Dervin (1997), Johnson (2003, 2009), and Sonnenwald (1999). It is argued that a context is larger than a situation and may consist of a variety of situations; different contexts may encompass different types of situations (Sonnenwald 1999: 3). Contexts are frameworks for meaning and reference and include interacting and contextualising elements, components, rules, resources, boundaries, constraints, privileges, individual and social actions and processes (Courtright 2007; Sonnenwald 1999). There are changes and movement in context (Courtright 2007: 290) and time and spatial factors are important in demarcating context (Dervin 1997). Johnson (2009: 596) distinguishes three senses of context: situational approaches (context is seen as equivalent to the situation in which an individual is immersed); contingency approaches (including the active ingredients that have specific, predictable effects on various processes); and major frameworks for meaning, systems and interpretation. Multi-contextuality and multi-dimensionality also feature in discussions of context: Johnson (2003: 736) refers to multi-contextual approaches to understanding processes, Dervin (1997) to different senses of context and Fourie (2010) to a multi-contextual approach to palliative care.

In a review on conceptualisations of context Courtright (2007: 286) notes among others the interpretation of 'context-as-container'. The container serves as backdrop to information behaviour. Although other interpretations of context, such as person-in-context and socially constructed contexts (Courtright 2007: 287-289), are very important for fully understanding the complexity of information behaviour, the current paper only focuses on the interpretation of container and identifying multiple containers as a first step in understanding the complexity of information behaviour in palliative care before moving to deeper analysis, such as person-in-context.

If one accepts this view, the interrelated conditions applying to palliative care, as discussed earlier, can specify a context of palliative care (i.e., the container) for studying information behaviour. This paper argues that to deepen understanding of what people in palliative care face and how this affects their information behaviour and ability to recognise and express information needs, we need to identify the multiple contexts that relate to and are part of palliative care to be studied in their own right.

What do patients in palliative care face?

Describing palliative care as the inevitable result of a diagnosis of a life-threatening disease or as the end of curative care and the start of care aimed at pain control, comfort, relief of suffering and quality of life does not fully reflect what patients and their families face: bodily and sometimes mental deterioration; isolation and stigmatisation; intense, unbearable pain; anxiety; anger; immense sadness; depression; feelings of loss, including loss of identity, personhood; physical exhaustion; symptoms such as shortness of breath and nausea; thoughts of suicide (Lawton 2000). They, however, also face opportunities for transcendence, insight and closure (Kuebler et al. 2007:xv ).

The patient's period in palliative care may be brief (a few days, a week or two), or last a year or more, leaving room for information to make a difference, as patients and their families face many challenges, uncertainty, fear, and confusion (Davies et al. 2010). Death may follow quickly on learning that there is no cure, or a patient may rot away. It may be an immediate diagnosis, or there may be a transition phase (Friedrichsen 2002) from a diagnosis of cancer to multiple metastatic (incurable) cancers. Koedoot et al. (2004) refer to watchful-waiting.

Need to deepen understanding of information behaviour in palliative care

Concerns about unmet information needs and frustrations related to palliative care continue to be raised (Baker 2004; Davies et al. 2010; Docherty et al. 2008; Fourie 2008). These are best revealed in the voices of patients, families and caregivers, as in the study reported by Davies et al. (2010). Parents who were not given information described feeling lost, alone, frustrated, sad, distressed, confused, helpless, angry and in the dark about what to do. Negative experiences with information provision have been linked to experiences of guilt long after the death of a loved one, more intense long-term grief, dissatisfaction with services, and distrust (Davies et al. 2010).

Although health care professionals are aware of the need to provide patients with information (Fourie 2008; Iconomou et al. 2002) and especially of the importance of appropriate and effective communication (Friedrichsen 2002), it seems as if they do not fully grasp that providing information, answering questions and offering emotional support address only a small part of information behaviour. Although the inability of people to recognise information needs and the difficulty of expressing and formulating such needs are well recognised in information science literature (Taylor 1968; Wilson 1999), these difficulties do not feature strongly enough in research reports from the health sciences, especially those on health communication and patient education.

Complexity of information behaviour in palliative care and influencing factors

In various contexts (academic, workplace, everyday life) information needs and information behaviour have been noted as complex, cyclic, dynamic, evolving and often unpredictable (Case 2007). For life-threatening diseases, such as cancer, and palliative care it has been reported as diverse; between patients and also between patients and family members (Clayton et al. 2005; Fourie 2008). In palliative care, information behaviour is influenced by numerous factors, such as education, coping style, culture and age (Fourie 2008; Friedrichsen 2002; Davies et al. 2010). Moreover, it is emotionally laden. Cross-influencing of information behaviour occurs between actors: the information behaviour of patients may be influenced by family members or health care professionals (Baker 2004; Fourie 2008). In the context of cancer it has been observed to be irrational (Johnson 1997). Not everybody wants information; some actively avoid it (Case et al. 2005). Not all information needs are recognised or well expressed (Case et al. 2005; Kirk et al. 2004); sometimes people cannot find the right words to express themselves (Taylor 1968). They may be too shy, their self-esteem may be low, or there may be a language barrier (Davies et al. 2010). 'It is part of my low self-esteem' was reported as the reason for not asking questions, in a study by Fourie (2008).

Studies of information behaviour rely too much on the ability of patients, family members and others to identify information needs and information-related actions and their ability to express and formulate such needs and actions. Such studies of expressed information needs often form the basis for interventions to support patients (Kirk et al. 2004). Although very valuable, many information needs may not be recognised and adequately expressed, and thus remain unsatisfied. The difficulty of expressing information needs is also evident from the work of Taylor (1968) on the difficulties in question negotiation.

Growth in palliative care and the need for interventions

In view of more older people facing chronic diseases (Kuebler et al. 2007: xv), more cancer patients and the information needs related to the HIV/AIDS pandemic (Veinot 2009), information behaviour in palliative care needs to be reconsidered to improve communication, patient education and counselling, support in decision-making, information provision, information transfer and the design of information services. Although they may face the end of life, patients have many decisions to make, e.g., on life-sustaining support, living wills and treatment such as palliative chemotherapy (Koedoot et al. 2004). Often families need to make decisions on behalf of patients, such as when and whether to enter a hospice or to stop life support (Davies et al. 2010).

Exploratory reflection on the diversity of contexts faced in palliative care

Although the idea of multiple contexts has been noted before (Dervin 1999; Johnson 2003, 2009), information behaviour studies often focus on a single context, e.g., academic, workplace, subject field or profession. When questioning patients in palliative care about their information needs and information behaviour they can only express the needs they are aware of and recognise (thus, not revealing dormant information needs). They may forget about some needs, or the need may not be evident at the time they are questioned. They may lack the ability to express themselves clearly (as seen in the work by Taylor 1968), or they may experience a language or cultural barrier (Davies et al. 2010; Fourie 2008). They may experience primary needs, such as physical or psychological needs, but may not realise that information may help them to make sense of the situation e.g., the need to understand what happens when dying or to cope with relationships.

Accepting that the inter-related conditions for palliative care can demarcate context-as-container for palliative care where patients experience their illness and where their information behaviour manifests, it is argued that we need to identify and label other contexts that are part of or related to palliative care. These can be studied in their own right. A content analysis of the literature of each context in relation to palliative care might reveal dormant information needs and primary needs being translated into (secondary) information needs. It might reveal psychological, emotional, cognitive and other influences affecting information behaviour and dynamics not otherwise noted. Such a content analysis can be followed by collecting data from patients and others affected by palliative care, by asking different questions to avoid getting the same answers.

Figure 1 depicts an exploratory model of multiple contexts in palliative care. The palliative care patient, diagnosed with a life-threatening disease such as cancer or AIDS, is surrounded by other people; these may be family members (parents, siblings, children), nurses, doctors and communities (e.g., a religious congregation). The patient may recognise a gap in his/her knowledge (i.e., an information need) and act on it. Actions can include information seeking or any other action encapsulated by the concept information behaviour, such as ignoring the gap or not recognising it. The people around patients may influence their information behaviour.

If palliative care is interpreted as ending curative care, the patient and others are awaiting death. They may be aware that palliative care implies dying (i.e., awareness of death) or not. Their awareness will depend on the information they received about the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Even if aware of the diagnosis and impending death, they may hope for a miracle and believe that acknowledging the inevitability of death will show lack of faith. Patients may be experiencing immense, unbearable pain. Patients and families may immediately relate the cancer (brain, lung) or the disease trajectory (metastases) to dying, or they may believe that it is curable; 'I only want to know what it means to be called a survivor', a participant with breast metastases said during a study by Fourie (2008). Patients may find themselves in a hospice where patients eventually die. There may be a network of people supporting them; family, friends, people from church, interaction through the Internet, or they may be on their own. Figure 1 depicts multiple contexts that need to be studied to deepen understanding of information behaviour. It includes contexts that are considered part of palliative care and identified from the inter-related conditions set earlier for palliative care, namely the context of informing the patient, context of awareness of the disease, context of location of the disease and the disease trajectory, context of pain (these four contexts relate to the condition for diagnosis with a life-threatening disease), context of phase of the disease and context of institution of care. The context of a supportive and social network is offered as one that is not part of the conditions for palliative care, but that can be related to palliative care. These contexts serve as examples only to support the argument for the exploratory model; there are many more contexts to be identified and labelled, as also shown in Figure 1. Various other elements and processes of palliative care (as part of its inter-related conditions) can be studied as contexts, e.g., hope (Curtis et al. 2008), communication (Davies et al. 2010), coping (Barnoy et al. 2006), culture (Davies et al. 2010) and treatment (Koedoot et al. 2004). The contexts are depicted as open spirals to show their evolving nature. During the illness and time in palliative care a patient may, for example, move from home care to a hospital ward to a hospice (i.e., location of care). Although the circle of contexts in which the patient and other actors find themselves in palliative care show links, the figure, for purposes of clarity, at this stage does not depict overlaps in the contexts.

The following sections briefly discuss the contexts depicted in Figure 1, based on a very basic review of the literature to illustrate the value of the exploratory model; each context justifies a full content analysis with special reference to palliative care and information behaviour. The context of informing and disclosure is discussed in rather more detail since it is a prerequisite for instigating and expressing information needs.

Context of informing and disclosure

In health care, disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis, and giving information to patients, are fields of study in their own right. Doctors wishing to empower patients and families to participate in shared decision-making need to share appropriate information with them. The chances of patients recognising a gap in their knowledge (anomalous state of knowledge) (Belkin et al. 1982), trying to make sense of a situation and bridging the gap through information seeking (Dervin 1999) is small if they are not fully informed about the diagnosis of a life-threatening disease and the prognosis. Without full disclosure there may be no or only partial recognition of information needs related to the disease, symptoms, treatment, care to be taken, expected quality of life, arrangements required, etc. There may be no or only partial knowledge of the terminology to use when asking questions or seeking information.

Doctors, frequently noted as the preferred and trusted information resources, may shy away from full disclosure. They may be influenced by their worldview, health care beliefs and preferences in sharing information; they may be uncomfortable with discussing a poor prognosis, death and dying; they may experience time constraints and limitations in their training on communicating "bad news". Many issues are at stake: the clarity of their explanations, completeness of the information provided, choice of words, body language, compassion and empathy portrayed, educational level of communication, tone of voice, timing and privacy of communication, and cultural sensitivity (Davies et al. 2010; Fourie 2008; Kirk et al. 2004; Koedoot et al. 2004). They may try to soften the blow by using gentler terms, which might not convey the implications and reality of impending death.

There are differences of opinion on how much information should be shared and the value of sharing. Apart from the opinions of health care professionals and the community, family members and patients may differ in their preferences for full, partial or no disclosure (Curtis et al. 2008; Kirk et al. 2004). A big concern is how disclosure will affect hope and the desire to live (Curtis et al. 2008). This introduces the context of hope and its balance with the contexts of informing and awareness. In trying to ensure that patients do not lose hope, explanations are sometimes clouded by false reassurances, causing confusion. In deciding on disclosure, doctors often rely on their interpretation of the patient's readiness to deal with a diagnosis, but they may misjudge this.

Information to share includes: diagnosis (e.g., metastatic brain cancer), prognosis (e.g., advanced and poor, with some hope versus terminal), treatment (e.g., pain management, palliative chemotherapy), institutions of care (hospice or home care), and the disease trajectory (i.e., the course it will take). Providing such factual information is, however, not sufficient; patients and their families have also reported emotional information needs (Fourie 2008).

Being informed does not imply understanding. Information needs to be explained and contextualised so that people will understand and relate to it. Depending on the patient's openness and readiness to receive the message (educational level, cognitive ability, emotional level, levels of stress, anxiety, state of shock, grasp of words, etc.) and how it is explained (as set out in the preceding paragraph), s/he may be informed or not. Patients interact with other people and information resources, including family members, the Internet and acquaintances. This could add to confusion or could support explanations by health care professionals. Especially linguistic and cultural differences challenge the ability to share information adequately and inform patients and their families (Davies et al. 2010:e863). A non-English-speaking parent with a child in paediatric palliative care explained:

Mostly, the impotence due to the language barrier… there are many terms we don't understand. They might be simple, but since their language differs from ours, that made me feel impotent. Also fearful… fear was always there (Davies et al. 2010:e861).This introduces the context of communication. Even if patients are not informed about the diagnosis or prognosis, they may suspect something is wrong and seek information on their situation in all possible ways (Glaser & Strauss 2005). This may lead to the wrong conclusions and their own explanations, adding to confusion and anxiety (Davies et al. 2010: e861).

In the preceding paragraphs a few issues on the context of informing were noted to point to its complexity and impact on the ability of patients to recognise and express information needs, as well as their ability to use the right words to ask questions and seek information. Context of informing can overlap with many other contexts (only a few are indicated here) such as communication and country-specific legislation on disclosure. The context of informing has an impact on the context of awareness and contexts of support and social networks, i.e., what people know and what they are aware of when they start interacting with others and sharing experiences. It is influenced by the contexts of culture, hope and many more.

Context of awareness and recognition

If patients and their families are not informed about a diagnosis and poor prognosis, they may experience blissful ignorance and feel no need to fill gaps in their knowledge or try to make sense of what is happening. They may either be unaware of a need for information or suspect that something might be wrong and employ strategies to confirm their suspicions (Glaser & Strauss 2005). This may lead them in the wrong direction and raise the wrong information needs.

Even when fully informed about the diagnosis and prognosis, they may not be aware of the seriousness of the situation and impending death, or if aware, they may prefer not to admit it and not to talk about it (Glaser & Strauss 2005). Even if they admit that they are dying, they may still experience flares of hope, which may affect their information needs and information behaviour e.g., a need to talk to survivors or to hear about miracle cures (Fourie 2008). There may be shades of awareness, e.g., awareness of being in palliative care, but no real awareness that it implies death and dying. Friedrichsen (2002) refers to the 'later palliative phase' - implying a more serious stage, closer to death.

Apart from full disclosure on the disease and prognosis, many factors may stimulate or inhibit awareness. Those in a hospice may be more aware that death is impending than those in home self-care (Lawton 2000). Hannan and Gibson (2005) report on how parents decide on a final place for their children to die; they are aware of impending death. Awareness of dying does not imply acceptance; there may be constant interplay between acceptance and denial, as well as selective awareness, such as awareness of the diagnosis and its seriousness, counteracted by hope and religious beliefs to block deeper awareness. Treatment such as palliative chemotherapy, where chemotherapy is associated with cure, may also confuse awareness of death. Awareness of the seriousness of their situation and dying does not imply awareness of all issues related to their illness: the care, the impact on their families and informal caregivers, etc.

Context of pain

Pain and pain management are fields of study in their own right. Although patients and their families often mention needs for information on pain management, the literature on information behaviour does not fully reflect the complexity of pain in coping with a life-threatening disease. There may be no or little pain, or immense and unbearable pain in spite of heavy medication; it may be pain in the bones, headaches, intestinal colic or visceral pain.

The chronic pain of cancer is quite unlike the acute pain of trauma or the resolving pain of the postoperative period. These pains are easily understood, and even borne, when recovery is expected in a short time (Saunders et al. 1995: 12).

Caregivers feel responsible for supporting patients to cope with pain, but they are unfamiliar with it. They are often confused by myths and unnecessary fears such as a (dying) patient becoming addicted to morphine and other means of pain control. A study of pain as a context in palliative care may show means to support patients and their families to recognise dormant needs for information and to express their questions and information needs adequately. Much more about pain and pain management, especially in palliative care, needs to be considered before we can meaningfully collect data from patients on their information needs and information behaviour.

Location of disease and disease trajectory as context

Differences in information behaviour have been noted related to different cancers (i.e., different disease locations such as the lung, breast or prostrate) (Johnson 1997). If multiple cancers (i.e., different locations) or metastasis (i.e., a change in trajectory) is diagnosed, patients' context, experience and expectations may change to reflect not only the disease trajectory becoming more serious, but also changes in the information needed and information behaviour. Even in palliative care, some patients still ask questions and may make their own decisions for months (Fourie 2008). There are also the terminally ill phase and days before death when patients may be unaware of their surroundings, but when their families may have many questions.

Context of care

Palliative care is closely associated with hospices (Lawton 2000; Saunders et al. 1995). Although a growing number of patients prefer to be cared for and die at home, others prefer hospitalisation, day-care centres or hospices. Those in hospices are generally more aware of death and dying, noting the rapid deterioration of others. A hospice sharpens especially families' awareness of death. Sometimes families (e.g., parents) receive too little information about hospice services (Davies et al. 2010). Much depends on how doctors describe hospices, how much they themselves know about hospices and whether they are merely referring patients to hospices, or whether they actually discuss the options; patients and families have admitted not knowing about valuable hospice features and services (Casarett et al. 2004 ). Ignorant of the options hospices offer, they may tend not to seek information on hospices. Understanding the philosophy and service orientation of hospices, as well as the reported experiences of patients in hospices, can direct the questions we ask on the information needs and information behaviour of patients.

Context of supportive and social network

In the final phase of life some patients experience isolation. Others have good support from their social network (spouses, fathers, mothers, siblings, children, friends, colleagues, acquaintances, etc.) and seem to do better; they seem to have fewer needs for information and support from health providers. In such social networks each participant has his or her own experience and understanding of the situation, emotions, fears, perceptions and roles they accept or assume they should fulfil. They have their own personalities and coping styles (Barnoy et al. 2006). The dynamics and interaction in the close family circle is important, but there are also many other people who can influence the experiences and information behaviour of patients. These include health care professionals (doctors, nurses, social workers) and even voluntary workers. Of special importance is how well people in such a supportive and social network is informed, their awareness and recognition of the disease and prognosis, their understanding and the way in which the interaction and dynamics with the patient and others can stimulate or prohibit information behaviour.

Conclusion

The preceding discussion argued for an exploratory model (Figure 1), reflecting patients' experiences of gaps in knowledge that can become information needs. All actions related to such gaps are part of their information behaviour. From the inter-related conditions that should be met to refer to palliative care, many contexts can be identified, which if studied in depth in their own right, e.g., by means of a literature review or content analysis, can be used to deepen understanding of the complexity of information behaviour in palliative care, noting dormant information needs and primary needs that can be translated as (secondary) information needs. Such findings can change the questions asked in data collection from patients, leading to new answers and deepened insight. Only a few contexts were briefly discussed here to show their potential for further study; there are many more contexts to identify and label. These contexts are depicted as open spirals in Figure 1; they evolve during the patients' illness and time in palliative care, and they are influenced by other contexts. Studying any context or a combination of contexts in isolation will not offer a holistic view of information behaviour in palliative care, but may contribute to a more solid model of information behaviour and supporting theories. Studying these contexts may also reveal new or different ways for data collection than currently reported.

Although other contexts such as academic contexts or professional contexts may seem less complex than palliative care, understanding of information behaviour in these contexts might be improved by applying the exploratory model (Figure 1). Regardless of the context, there will always be one or more individual(s) in such a context whose information behaviour manifests in a variety of ways, at different times and under different circumstances (i.e., any information related activity - including ignoring the gap in knowledge or information need, seeking information, not being aware of a gap in knowledge); people surrounding the individual(s) - even if it is only in a virtual sense; context-as-container, as defined by an accepted definition or description (including characteristics, boundaries, etc.) e.g., what is a university context, what is a school context, and what is the context of professional football? From such a definition (container or background to the context) other contexts can be identified such as a residential, distance, online, or virtual context for a university (i.e., the means of teaching), examination and studying as processes related to universities. Such contexts are part of the academic context (container), but are also larger in the sense that online academic contexts can also apply to professional development, and examination and learning can also apply to schools, or everyday life such as getting a driver's license. By identifying diverse, multiple contexts that are part of or related to the context being studied, labelling such contexts, and studying them in their own right as reported in the literature and in relation to the context being studied (as argued for the context of palliative care), dormant information needs, factors influencing information behaviour, different questions to ask in studies of information behaviour, and possibly even different ways of data collection might be identified. Considering input from the literature on different contexts, data collection can thus be enriched to deepen understanding of information behaviour in any chosen context; this argument, however, need to be tested, starting with palliative care for which this paper argued the complexity and urgency for deepened understanding of information behaviour.

Acknowledgements

With appreciation to Tina van der Vyver for converting the document to XHTML.

About the author

Ina Fourie is a full professor in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, South Africa. She received her Bachelor's degree in Library and Information Science, her Honours and Masters degree in Library and Information Science from the University of the Orange Free State, Bloemfontein (South Africa), her D.Litt et Phil from the Rand Afrikaans University, Johannesburg (South Africa), and a Post-graduate Diploma in Tertiary Education from the University of South Africa (Pretoria). She can be contacted at ina.fourie@up.ac.za