Coursework-related information horizons of first-generation college students

Tien-I Tsai

School of Library and Information Studies, University of Wisconsin—Madison, USA

Introduction

With the growing number of first-generation college students, many studies in education have been investigating the motivation, persistence, and academic performance of the students. Some studies focus on demographic characteristics (Ayala and Striplen 2002; Vargas 2004), while others focus on parent involvement and psychological characteristics (Acker-Ball 2007; Donatelli 2010). These studies reveal the disadvantages of first-generation college students in their college life and pointed out the need to understand them in order to help them more effectively. However, there is scant literature examining this specific population in the field of library and information studies. While Torres and her colleagues (2006) researched first-generation Latino students' seeking academic information, they only focused on how students use their out-of-class contacts and how academic support services can be improved. For the most part, first-generation college student-related literature has not yet extensively examined their information behaviour.

Using information sources effectively is important for academic success. Learning about students' information behaviour, including their information needs, information seeking, and use, can help us understand how to approach them as well as how to help them use available resources. This study examines first-generation college students' information behaviour through the theoretical framework of information horizons proposed by Sonnenwald (1999) to understand how to help students use information sources and lead a better life in college. The concept of information horizons provides a theoretical framework to examine individuals' information behaviour, especially as to identifying the sources people use and their source preferences. Previous research predominately used interviews with informants' map-drawings to learn their information horizons. Sonnenwald, Wildemuth, and Harmon (2001) emphasized the importance of triangulation, and employed a survey asking individuals' frequencies and preferences of information use in supplement to the above methods. Therefore, examining the frequency of source use and the prioritization in information horizon maps may help researchers develop a way to approach individuals' information horizons, to determine their use behaviour, and to advance research on the idea of information horizons.

According to the theoretical framework of information horizons, contexts and situations are important factors influencing an individual's information behaviour. Investigating relationships among sources used by individuals helps us learn about individuals' information-seeking strategies and preferences for information sources (Sonnenwald et al. 2001). Hence, studying what sources and how they are used in specific situations furthers our understanding of individuals' information horizons through the sequential relationships among sources they use.

Focusing on undergraduate students' coursework-related information behaviour, this study aims to understand first-generation college students' information source use and preferences as well as the typical steps taken in different situations. This study considered the following research questions:

- How frequently do first-generation college students use recorded information and human information sources and how do they position the sources on their information horizon maps across different coursework-related situations?

- How frequently do students consult their family members and how do they position family members as opposed to other sources on their information horizon maps? and

- What are the sequential relationships among the information and human sources that are used by students across coursework-related situations?

Literature review

First-generation college students

There are various definitions for first-generation college students. Some define first-generation college students as students whose parents did not attend college at all, while others define them as students whose parents did not graduate from a four-year college or university. According to Davis (2010), the bachelor's degree has been valued in the job market. People who do not hold a four-year degree have more difficulty finding a job that is higher in the job market hierarchy, and the way people view bachelor's degree makes students whose parents had some college education similar to first-generation students (Davis 2010). Moreover, most research universities include students whose parents attended some college but did not have a four-year degree as first-generation college students (Education Advisory Board 2010; CPRE 2007). Thus, this study adopted the definition of first-generation college students from Davis and defines first-generation college students as students whose parents did not graduate from a four-year institution.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 1999, 2001, 2005, 2011) and the Higher Education Research Institute (2007), 30% to 50% of the undergraduate students in colleges and universities across the United States are first-generation college students. Scholars note that these students tend to have a high drop-out rate compared to continuing generation college students (Ayala and Striplen 2002; Choy 2001; NCES 1999, 2001, 2005, 2011; Vargas 2004). Hence, helping first-generation college students adjust and transition into college has become an important issue.

Although education researchers have been studying first-generation college students for decades, they did not pay close attention to this student population until 2000s. Recently, many studies in education have been investigating the motivation, integration, adjustment, persistence, and academic performance of the first-generation college students (Acker-Ball 2007; Ayala and Striplen 2002; Donatelli 2010; Vargas 2004). Related studies showed the challenges encountered by first-generation college students attempting to excel in college(Choy 2001; HERI 2007; Jacobson and Williams 2000; NCES 2005; Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998). Many studies also emphasized students' demographic characteristics, their adjustment to college, academic performance, and retention rates (Choy 2001; HERI 2007; Jacobson and Williams 2000; Nava 2010; Nuñez and Cuccaro-Alamin 1998).

Torres and her colleagues (Torres et al. 2006) used a grounded theory approach to examine how first-generation Latino college students seek academic information. They proposed a model explaining the information seeking process of Latino students. According to their study, first-generation Latino students start seeking academic information from peers and pamphlets first, and then consult their advisors or mentors. Torres and her colleagues also claimed that the unclear role of the advisor as well as the untrusting relationship with advisors make students hesitant to seek help from advisor and other university services. Their study provided insights about the process of first-generation students' academic information seeking process in general. However, the study did not address how students' information seeking behaviour may change across specific coursework-related situations. Other information sources may also be important to the students in different coursework-related situations.

For instance, parents' involvement and encouragement seem to be a main factor in students academic performance (Acker-Ball 2007; Donatelli 2010; HERI 2007; NCES 1999). Relatives may also play an important role to help students' academic performance (Martinez et al. 2009). Thus, examining how students use their parents and other family members to get information or help in their coursework-related situations can help understand the roles of parents and other family members as information sources.

Finally, Davis (2010) indicated that higher education researchers have been investigating first-generation college students through qualitative approaches, and it is the time for quantitative analysis on the same topic to catch up. Thus, the present study employed a mixed-method research design to explore first-generation college students' coursework-related information behaviour.

Information horizons

Sonnenwald (1999, 2005) proposed the theoretical framework of information horizons to describe individuals' information behaviour. She contended that information behaviour may be viewed as 'collaboration among an individual and information resources' (Sonnenwald 1999: 186), and the information horizon map graphically represents information sources and individuals' source preferences (Sonnenwald et al. 2001). One's information horizons vary across contexts, situations, and social networks; therefore, the study of individuals' information horizons may help researchers understand their information seeking, filtering, use, and dissemination.

Savolainen and Kari (2004) further described horizon as an imaginary field and claimed that everyone has their own imaginary field upon which they position various information sources according to personal preferences. They concluded that this mental map is the information source horizon, and that perceived accessibility and quality are two main factors that influence people's information horizons.

There are various ways to examine individuals' information horizons. Sonnenwald asserted that using critical incident to conduct in-depth interviews and to facilitate information horizon map drawings can help effectively discern users' information horizons (Sonnenwald et al. 2001; Sonnenwald 2005). This may help researchers not only to understand the information sources individuals use, but also to explain the role of these information sources in the users' information seeking process. Furthermore, Sonnenwald and her colleagues indicated that surveys can be used as a triangulation in information horizon research. However, only Sonnenwald and her colleagues used a survey as a supplementary method in their investigation of eleven college students' information horizons (Sonnenwald et al. 2001).

When analysing information horizons, Sonnenwald and her colleagues (2001) used a matrix to illustrate students' preferred order of information resources. The resources were presented in the matrix and were sorted by the number of students who mentioned a resource and the total number of times a resource was mentioned by the students. Savolainen and Kari (2004) used three concentric circles to illustrate how users prioritize information sources according to their preferences. Huvila (2009) argued that drawing an analytical information horizon map based on interview data gathered by the researcher, instead of by the informants, may be more effective because such a map avoids the problem of informal and inconsistent notations among informants. In order to understand students' perception of sources, to solicit notations used in students' information horizon maps, and to allow for future questionnaire and interview design, this study used the informant's map drawings with a variation of Sovelainen and Kari's (2004) data analysis method by calculating weighted scores and compiling all students' maps into one map with concentric circles.

Overall, the information horizon is an evolving theoretical framework. Sonnenwald (1999, 2005) suggested that in order to enrich this framework, more empirical research in various contexts with various users is required. Nevertheless, only a few empirical studies have used information horizons to examine users' information behaviour, most of which have focused on everyday life or career-related contexts (Kari and Savolainen 2003; Savolainen and Kari 2004; Savolainen 2007). Some recent studies, however, have focused on graduate students' information seeking activities in research process (Tsai 2010; Chen and Tang 2011) as well as on undergraduate students (Tsai 2012; Sonnenwald et al. 2001).

Studies on the information horizons of graduate and undergraduate students have indicated that the two groups have markedly different information seeking behaviour. Sonnenwald, and her colleagues (2001) examined the information horizons of eleven college students of low socio-economic status, finding that the library was not a preferred information source for them, and was not placed on their information horizon maps. Studies of graduate students, however, showed that library resources appeared to be an important information source in their information horizons (Tsai 2010; Chen and Tang 2011). Therefore, undergraduate and graduate students' information horizons may be different because they have different levels of coursework-related tasks and goals. Researchers should investigate undergraduate and graduate students' information source use behaviour separately.

Methods

Participants

First-generation college students are hard to identify because there are no obvious traits to indicate parents' education levels and identification relies on students' self-disclosure (Davis 2010). Additionally, since parents' education is considered as confidential personal data, the university cannot reveal this even for research purposes. Therefore, an e-mail briefly describing this study was sent to all undergraduate students on campus to recruit first-generation participants. Only those interested voluntarily participated in the study.

Four hundred and fifty first-generation college students from a public university participated in the web survey: about 70% (n = 313) were female, and the rest were male. While most of the participants lived in dormitaries or off-campus housing, 12.3% (n = 55) lived with their family (including about 2% who lived with their siblings, cousins, spouses, in-laws or children). Nearly half of the students were first (27.6%) or second year (15.7%) students, and slightly over half of the students were third (25.1%) or fourth year (30.6%). About 71% (n = 316) of the participants were Caucasians, and the rest were American Indians, Asians, African Americans, Hispanics, or multiracial. Related to their parents' education, 48.4% (n = 218) of the participants had parents with no education beyond high school, and the rest had parents with some college education, a post-secondary vocational school degree, or a two-year college degree. Although 38.8% (n = 173) of the students did not have a part-time job in addition to their schoolwork, 14% (n = 63) of the students worked more than twenty hours per week. The demographic characteristics of the twelve interview participants were similar to those of the survey participants.

Data collection

This study employed mixed methods for data collection to increase the validity of the research. A web survey and follow-up interviews were used to collect data regarding students' coursework-related information seeking activities. Interview participants were also asked to draw an information horizon map to reflect the information sources they used.

The online questionnaire used in this study included demographic questions and questions about source use, developed based on related studies (Sonnenwald et al. 2001; Tsai 2012). The questionnaire was mainly framed with five different coursework-related situations, including: course content, course logistics, course selection, programme, and moral support. Under each situation four sets of questions were asked: the frequency of using information sources, the frequency of consulting human sources, the typical steps of using information sources, and the typical steps of consulting human sources. At the end of the questionnaire, participants interested in follow-up interviews were asked to leave their e-mail address. The volunteers were contacted and an in-depth interview was conducted with each of them, using an interview guide.

Using the critical incident technique, the interview guide included questions to further investigate source selection and use in different situations. Each interviewee was also asked to draw an information horizon map of general coursework contexts.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and inferential statistics such as chi-squared tests were used to analyse the source use among participants with different demographic characteristics. For analysing qualitative data collected from the in-depth interviews, NVivo 9 was used. Each of the interview participant was given a pseudonym (P1 to P12), and data were analysed in descriptive, topic, and analytical levels according to Richards (2009).

Findings

Information and human information source preferences and their use

As suggested by Sonnenwald and her colleagues (2001), information horizons can be used for learning which sources an individual uses, including how frequently an individual uses them. In the study's web survey, participants were asked to report the frequency of consulting particular information and human sources in five coursework-related situations. Results showed that course catalogues, university or department websites, and personal collections were the three most frequently used information sources (Table 1). Among human sources, peers in the same course or same department were the most frequently consulted (Table 2). In general, information sources were more frequently used than human sources.

In Table 1, search engines and personal collections were used frequently for course-content questions, while course catalogues and university or department websites were used frequently for course-selection and programme-related issues (Table 1).

| Information sources | Course content | Course logistics | Course selection | Majors and programme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course catalogues from the university site | N/A | N/A | 4.02 | 3.92 |

| Personal collections (e.g., printed course materials and those on course management systems, books you purchased) and syllabi. | 4.07 | 4.62 | 2.58 | 2.87 |

| Printed resources from the university library (e.g., books, journals, encyclopedia) | 2.59 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Online resources from the university library (e.g., e-journals from the database, e-books from the library) | 3.12 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| University and department websites | 3.48 | 3.55 | 3.61 | 4.19 |

| Search engines (e.g., Google, Bing, Yahoo) | 4.09 | N/A | 1.86 | 2.06 |

| Online forums or Q&A sites (e.g., RateMyProfessors, Yahoo Answers) | 2.87 | N/A | 2.42 | 1.74 |

| Social networking sites (e.g., Facebook) | 2.31 | 1.82 | 1.71 | 1.45 |

| Micro-blogging sites (e.g., Twitter) | 1.45 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.22 |

| Traditional mass media (e.g., TV, radio) | 1.91 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Other | 1.47 | N/A | 1.56 | 1.32 |

As shown in Table 2, peers in the same course were one of the most frequently consulted human sources across all situations. For course-content, course-selection, and program-related issues, peers in the same department were among the frequently consulted sources. Teaching assistants were often consulted for course content and logistical issues about the course, while advisors were consulted for course-selection and programme-related issues. Interestingly, roommates and parents who, generally, were rarely consulted, emerged as the second- and third-most often consulted human sources for moral support regarding coursework. According to Head and Eisenberg's (2010) survey of more than 8,000 college students at twenty-five educational institutions, about half of students at least sometimes asked their non-classmate friends, family members, or both for help with evaluating information for coursework, and 30% asked librarians for assistance. Contrary to Head and Eisenberg's findings, this study found that family members and librarians were not consulted often in first-generation college students' coursework-related information-seeking processes.

| Human Sources | Course Content | Course Logistics | Course Selection | Majors/ Program | Moral Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peers who take (or have taken) the same course you are/were taking | 3.93 | 3.33 | 3.86 | 3.49 | 3.23 |

| Peers who are in the same department with you | 3.55 | 2.65 | 3.47 | 3.44 | 2.77 |

| Friends from student organizations/ interest groups | 2.66 | 1.93 | 2.44 | 2.19 | 2.33 |

| Friends from a religious group | 1.41 | 1.22 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 1.46 |

| Friends who you met before college | 2.34 | 1.72 | 1.86 | 1.66 | 2.87 |

| Roommates | 2.87 | 2.30 | 2.45 | 1.99 | 3.19 |

| Professors you are currently taking (or have taken) classes from | 3.13 | 2.99 | 2.64 | 2.77 | 1.94 |

| Advisors | 2.55 | 2.06 | 3.55 | 3.85 | 2.20 |

| Teaching assistants | 3.51 | 3.42 | 2.39 | 2.57 | 2.05 |

| School teachers who you met before college | 1.69 | 1.35 | 1.53 | 1.53 | 1.56 |

| Librarians | 1.58 | 1.40 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.17 |

| Departmental staff | 1.76 | 1.60 | 1.69 | 1.74 | 1.32 |

| Parents | 1.86 | 1.41 | 1.80 | 1.76 | 3.20 |

| Siblings | 1.82 | 1.47 | 1.70 | 1.58 | 2.62 |

| Other family members or relatives | 1.53 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 1.24 | 1.60 |

| Other | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.16 | 1.13 | 1.59 |

The information horizon maps of first-generation college students

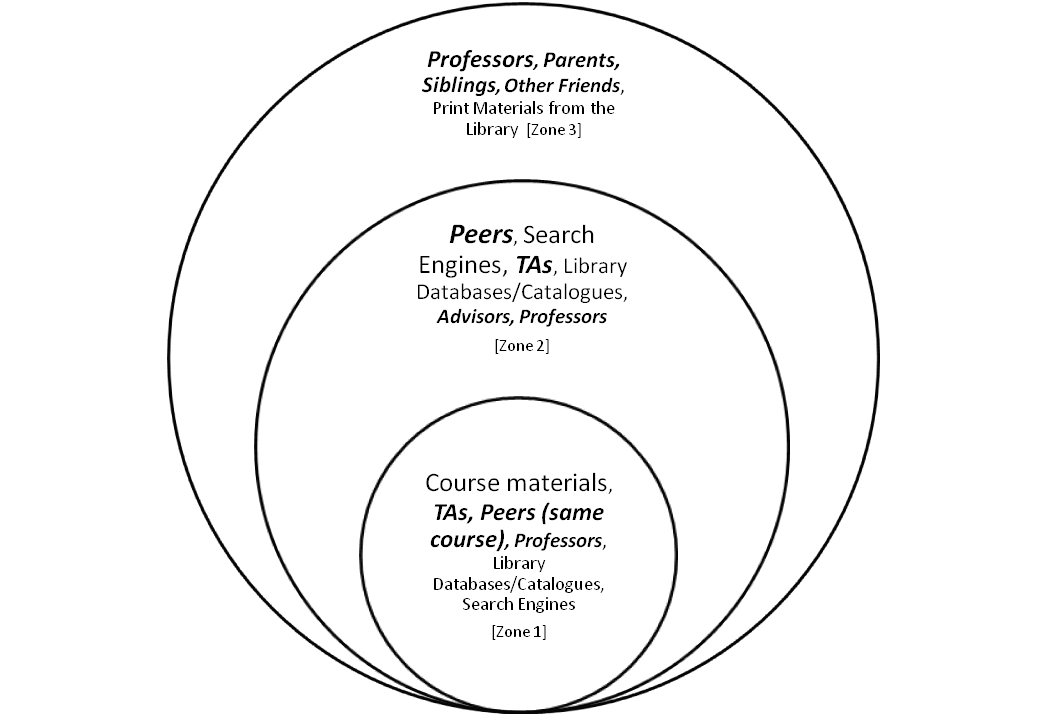

Twelve interview participants were asked to draw their coursework-related information horizon maps according to their preferences. The most preferred sources were to be placed in the central circle (zone 1), the second-most preferred sources were to be placed in the middle circle (zone 2), and the least preferred sources were to be placed in the outer circle (zone 3). The researcher adopted Savolainen and Kari's (2004) method of calculating weighted scores for each source that appeared on participants' maps (Table 3). The weighted score for each source was based upon the number of times a source appeared on students' maps; zone 1 sources were weighted by 3, zone 2 sources by 2, and zone 3 sources by 1. That is, a zone 1 source that appeared 3 times on students' information horizon maps would receive a weighted score of 9. The researcher further illustrated the concentric circle using different font sizes to represent the number of times a source appeared on students' information horizon maps. The more times an information source appeared on students' maps, the larger the font size would be (Figure 1); font size was determined based on the ordinal rank of number of times sources appeared in a specific zone.

Figure 1: First-generation college students' coursework-related information horizon map

Notes

1: Information sources and human sources were positioned by first-generation college students according to their preferences.2: Human sources are in bold and italics; TAs = Teaching Assistants.

3: Font size was determined based on the ordinal rank of number of times sources appeared in a specific zone.

While the average number of unique sources included in a map was only 8.92, a total of twenty unique sources appeared on participants' maps (Table 4). Nine different sources were positioned in zone 1 as the most preferred sources, and thirteen and fourteen different sources were positioned in zones 2 and 3 respectively as the second-most preferred and least preferred sources (Table 3). Among the twenty sources, course materials, teaching assistants, peers, professors, search engines, and library databases or catalogues appeared as the most preferred sources. Peers, search engines, teaching assistants, library databases or catalogues, advisors, and professors appeared as the second-most preferred sources. Finally, professors, parents, siblings, other friends, print materials from the library appeared as the least preferred sources.

| Zone | Number of different sources |

|---|---|

| 1 (central: most preferred) | 9 |

| 2 (middle: second-most preferred) | 14 |

| 3 (outer: least preferred) | 13 |

| Source type | Source | Zone | Number of times on the map |

Weighted score (zone 1*3, zone 2*2, zone 3*1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal collections | Course materials | 1 | 7 | 23 |

| - | 2 | 1 | ||

| Library resources | Library databases or catalogue | 1 | 4 | 21 |

| - | 2 | 4 | ||

| - | 3 | 1 | ||

| Other library resources | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Print materials from the library | 2 | 2 | 6 | |

| - | 3 | 2 | ||

| Online resources | Course Websites | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Other Websites | 1 | 2 | 8 | |

| - | 2 | 1 | ||

| Search Engines | 2 | 6 | ||

| University Website | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| - | 3 | 1 | ||

| Human sources | Advisors | 2 | 4 | 9 |

| - | 3 | 1 | ||

| Librarians | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Mentors | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Other Friends | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Other Relatives | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Parents | 3 | 5 | 5 | |

| Peers (same course) | 1 | 6 | 29 | |

| - | 2 | 5 | ||

| - | 3 | 1 | ||

| Peers (same department) | 1 | 2 | 19 | |

| - | 2 | 6 | ||

| - | 3 | 1 | ||

| Professors | 1 | 4 | 24 | |

| - | 2 | 3 | ||

| - | 3 | 6 | ||

| Roommates | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Siblings | 2 | 1 | 6 | |

| - | 3 | 4 | ||

| Teaching assistants | 1 | 7 | 32 | |

| - | 2 | 5 | ||

| - | 3 | 1 |

Course materials were the only source that appeared solely as the most preferred sources in zone 1, while course and other Websites, and search engines appeared in the first two zones. These showed students agreed that course materials were the most preferred source, and online resources in general were also preferred sources.

Most frequently used sources from the survey, such as course materials and search engines, were placed as the most preferred and second-most preferred sources (sources in zones 1 and 2) on students' maps. And less frequently used sources from the survey were typically placed as the least preferred sources in zone 3. For example, course materials and search engines were both highly preferred and frequently used by students across different situations. Librarians, roommates, and other relatives were not frequently used and only appeared as least preferred sources in zone 3. It is worthy of note that sources that only appeared in zone 3 were all human sources.

Family members in information horizons

According to literature in education, parents and other family members play an important role in first-generation college students' academic performance (Acker-Ball 2007; Donatelli 2010; HERI 2007; NCES 1999). This study investigated parents and other family members' roles in students' information horizons.

As indicated in the Web survey, first-generation college students did not often consult their parents, siblings, or other relatives across most coursework-related situations (Table 2). Not many students included parents in their information horizon maps, either (Figure 1). Students who included parents on their maps admitted in the interview that they did not share details about coursework-related issues with their parents. Some pointed out that they would consult their parents only when they needed coursework-related moral support. Some typical responses were:

they [my parents] have no idea what I'm doing. I just tell them how many exams I have or how many papers I have to write, so they know it's a lot. (P3)

For example, I told them how many exams I got, but they [my parents] don't really know what that means. They don't know how much work is that [sic]...

All in all, the results regarding siblings and other relatives from the interviews and the information horizon maps matched those from the web survey. Nevertheless, parents appeared in several participants' information horizon maps but received a low frequency of use in the web survey (Table 2). Although students claimed that their parents do not understand their college life, and parents are not usually the first source they go to for moral support, a few students still consult or talk to their parents when they need moral support. Many students also indicated that among the five coursework-related situations moral support is the most important because it is what motivates them to focus on their coursework.

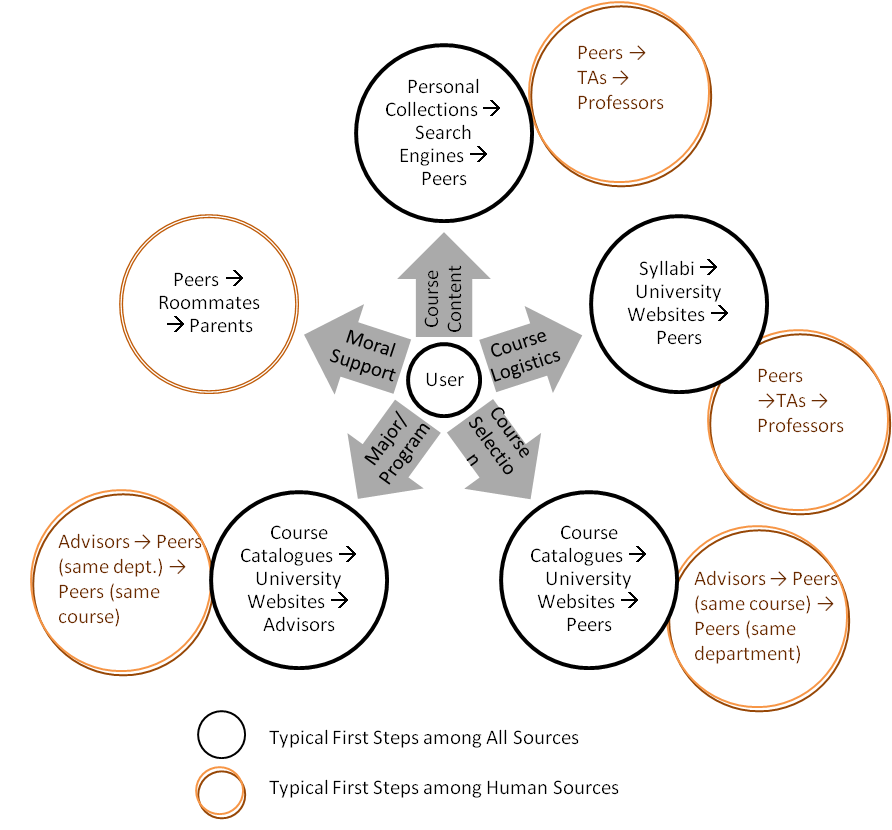

Sequential and referral relationships among information and human sources

As information horizons emphasizes the relationships among sources, this study explored the sequential steps of students to understand their source preferences. Based on the web survey data, typical steps taken by first-generation college students across different coursework-related situations are presented in Figure 2. Except for program-related issues, the first human source students tended to consult was peers. Only in the situation of program-related issues did advisors become the first human source students typically consulted (Figure 2). Results from both the web survey and the interviews showed this tendency of starting the coursework-related information seeking process from information sources, especially online resources, rather than human sources.

Figure 2: Sources used by first-generation college students across coursework-related situations (typical steps)

Note

TAs = Teaching AssistantsIn Figure 2 (derived from the Web survey), the sequential patterns of seeking course content information were similar to the patterns of seeking logistical information related to the course. As for information sources, students tended to start from their course materials. When looking for logistical information, students especially started from their course syllabi (either online or printed). Students then went to other online sources such as search engines and university websites. Finally, students talked to their peers to get more information.

As for human sources, students also typically followed very similar steps when consulting course content and logistical issues related to the course. Students tended to start from peers, especially peers taking the same class, then turn to teaching assistants and, finally, to professors. The reasons, mentioned in the interviews, for going through these steps were mainly related to the perceived accessibility of sources. Some participants mentioned that it was easier to consult peers because they felt more comfortable talking to peers, and they also saw their peers more often.

This phenomenon may be explained by students' interpretation of source preferences in the interviews and Kim and Sin's (2011) study on the perception and information use of undergraduate students. Kim and Sin (2011) found that sources perceived as accessible in economical, physical, and psychological senses are frequently used by students. In this current study, students pointed out in the interviews that both perceived accessibility and perceived importance of a source influence their information horizon maps. Most students indicated that teaching assistants and professors know a lot and are willing to help but may not always be available.

Not surprisingly, the sequential patterns for course selection and program-related issues resembled one another (Figure 2). That is, students tended to start from information sources before consulting human sources. Students went to course catalogues and university websites before talking to peers or advisors.

To sum up, the first three steps students typically took when seeking coursework-related information (Figure 2) basically matched their information horizon maps (Figure 1). Sources used as the initial steps were usually online resources placed in preferred zones; human sources that only appeared in the least preferred zone were usually not the first steps students indicated in the survey. Students seem to agree that human sources were not the first source they would consult in various coursework situations. Additionally, students revealed in their interviews that they may not take the third step unless they think the issue is crucial or the question or problem cannot be not resolved after taking the first two steps. This can also be explained by Lu and Yuan (2011) that individuals tend to consult people rather than seek information when they have high-level information needs. When students have a higher information need, they would take a further step to consult human sources. On the contrary, if students do not a have high-level information need, they might only seek information sources instead.

Besides online sources, peers and advisors played important roles in referring information to first-generation college students. Many students mentioned in their interviews that they learned to consult some useful sites from their peers or advisors. When talking about the most challenging aspects of attending college, some students reported that since they were the first person in their family to attend college, they had no idea what college life and coursework would be like. Thus, they simply talked to their fellow students and followed what their peers did because they felt that they did not know what they needed to be accomplishing at certain points in college and were quite anxious about falling behind. For example,

Basically I just see what others are doing, and I'll do the same thing, but I wish there were a way I could figure it out earlier… (P4)

My friend told me the site [sic], so I looked it up, and I found it helpful. (P10)

Discussion and conclusion

The study investigated first-generation college students' coursework-related information horizons and found that students prefer using different information and human sources in different coursework-related situations. However, personal collections and online sources are used across various situations. Among human sources, peers seem to be an important source in coursework-related contexts. Although students position peers in different zones on their information horizon maps, they always include peers as one of the first three sources consulted. While students placed library resources on their information horizon maps, some of them pointed out in the interviews that they only use library resources when it is required in class. Therefore, in order to help first-generation college students better handle their coursework-related issues, librarians should do more to promote library services, and the university should do more to facilitate information exchange among students. For example, instead of offering traditional lecture-based information literacy workshops, university libraries may incorporate interactive and multimedia elements into those workshops. It would also be important for the university to foster and support student organizations concerning first-generation college students.

Moreover, even if parents are not frequently consulted across most coursework-related situations, parents seem to be one of the important sources when it comes to moral support. And many students believe that moral support is important because it helps them stay motivated in college. Therefore, besides having a peer supporting system, maintaining this family support system in addition to other academic services may also help students move along well in college. The university may develop and promote parent program or parents council to connect students' families with the university in various ways, such as newsletters, outreach events, or campus visit. This may increase family involvement so that students' families may be better able to support them.

Even if most source preferences, as shown on students' maps, match the frequencies of use reported in the survey, there are still some discrepancies between the frequency of use, the number of times a source appeared on students' information horizon maps, and the weighted score of each source. These discrepancies are especially observed in human sources. Sources with high weighted scores, such as teaching assistants and professors, are not necessarily the most frequently used sources. Instead, these sources are perceived as important sources that most students utilize in different information seeking stages, and they are typically used as the second or third step in the information seeking process. Thus, examining sources that receive high weighted scores as shown on the information horizon maps but are not frequently used as indicated in the survey may help us better understand first-generation college students' concerns. Likewise, in order to learn what first-generation students value the most and what concerns they have, we need to further analyse the reasons why students' preferences vary.

Regarding the sequential relationships among sources, first-generation college students usually start with information sources rather than seeking help from human sources. The typical information-seeking sequential patterns for course-content and logistical questions are similar, and the patterns for course-selection and program-related issues are similar. The sequential patterns as indicated in the survey and in the interviews show that students usually consult peers before TAs and professors in various situations because peers are perceived as more accessible source. It is important to think about how to make various on-campus services and resources more accessible to first-generation college students. For instance, professors and teaching assistants may need to clearly declare in class what office hours are meant to be and provide alternative ways for students to easily access them, such as an online discussion board for course-related questions and answers.

Overall, this study expands the scant literature not only in first-generation college students but also in information horizons studies. It would also help facilitate planning appropriate orientation programs and workshops for first-generation college students and help students better adjust and transition into college.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Kyung-Sun Kim for her insightful suggestions on this paper.

About the author

Tien-I Tsai is a doctoral candidate in the School of Library and Information Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. She received her Bachelor's degree in History (with a minor in Library and Information Science) and her Master's degree in Library and Information Science from National Taiwan University, Taiwan. She can be contacted at: ttsai5@wisc.edu