Organizational strategy and competitive intelligence practices in Malaysian public listed companies

Ching Seng Yap, Md Zabid Abdul Rashid and Dewi Amat Sapuan

Universiti Tun Abdul Razak, Capital Square, Block C & D, No. 8, Jalan Munshi Abdullah, 50100 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Introduction

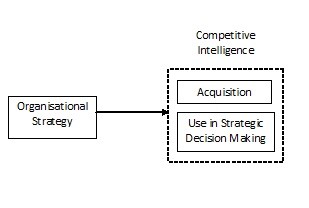

Being a relatively new management tool in the business world, competitive intelligence plays an important role to support managers today for better decision making and strategic planning. Competitive intelligence is defined as a systematic and ethical programme for gathering, analysing, and managing information about the present and future behaviour of competitors, suppliers, customers, technologies, government, acquisitions, market and general business environment (Vedder and Guynes 2000 ). Businesses today have some sort of competitive intelligence practices, whether conducted formally or not. Cases occur where competitive intelligence brings positive impacts on firm performance in different areas, for instance, Merck & Co., NutraSweet, Texas Instrument, Shell, East Kodak Company, Motorola, AT&T, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, Marion Merrell Dow, FMC & Corning (Gilad 1989 ; Rouach and Santi 2001). Despite the increasing importance of competitive intelligence in businesses, there are few systematic attempts to investigate the relationship between competitive intelligence practices and its antecedents and consequences. Previous studies reveal that current evidence of the value and impact of competitive intelligence is anecdotal or consists of indirect assessment (McGonagle and Vella 2002). The existing empirical studies are mostly from the Western countries with limited studies from the emerging economies. Therefore, this paper aims to investigate the level of competitive intelligence practices undertaken by Malaysian companies and examine whether a difference exists in competitive intelligence practices between companies that adopt different organizational strategy.

This paper proceeds as follows. The next section reviews the foundation concepts of organizational strategy and past empirical studies with respect to competitive intelligence practices and its link to organizational strategy. The third section describes sampling procedures, data collection method, and variables and measurement, and the fourth section presents results and discussions. The paper concludes with an examionation of implications, limitations, and recommendations for future studies.

Review of the literature

Organizational strategy

The word strategy was derived from the Greek word strategos which means the art of the [military] general (Cohen 2004:10). The concept of strategy was introduced into organizational literature and advanced most notably during the 1950s by the Harvard Business School (Miles and Snow 1978; Snow and Hambrick 1980). There is no single, universally accepted definition of strategy in the literature. Hambrick (1980: 567) defined strategy as a pattern in a stream of important decisions that guides the organization in its relationships with its environment, affects the internal structure and processes of the organization and centrally affects the organization's performance. Strategy can also be defined normatively, that is the content of a strategy should include the company's basic image, purposes, fields of present and future activities, and expected future position in these fields (Aguilar 1967: 4).

In conceptualizing organizational strategy, Miles and Snow (1978: 153) portrayed business as continuously cycling through set of decisions on three broad problem areas which constantly confront management: the entrepreneurial problem - what products or services and market should the organization select; the engineering problem - what is the appropriate process or technology for assembling and delivering the product or services; the administrative problem - what should be the structure and managerial processes for controlling and coordinating the activities of the organization. Based on research in four industries, they distinguished groups of companies that deal with the three problems in a relatively similar manner. The respective groups may be designated as strategic typologies - prospector, defender, and analyser.

The three effective strategic types are neither inferior nor superior among themselves. Each type has its own unique strategy for relating to its chosen market, a particular configuration of technology, structure, managerial process, risks and power distribution that is consistent with its market strategy. It means any three strategic types will perform well so long as their strategy implementation is effective. Defenders have narrow product domain, compete primarily based on price, quality and services. They focus on tight control and cost efficiency and pay less emphasis on technological changes. As such, the organizational structure tends to be more formalized and centralized to facilitate intensive planning. Prospectors focus on new market opportunities and compete primarily through new product innovation. They attempt to be the first mover in the market and thus ability to capitalize technological changes and research and development are of utmost importance in determining their success. In order to adapt to the rapid changing environment, the organizational structure and administrative system of prospectors is more flexible. Analysers are the hybrid types of organization, combining the features of defenders and prospectors. They emphasise production and cost efficiency while innovations are selectively adopted in promising new market. As such, they tend to be second mover in the market after prospectors. The organizational structure tends to be more complex, integrating centralization and decentralization to suit the different markets. The fourth type of organization is called the reactor, which is a form of strategic failure in that inconsistencies exist in its strategy, technology, structure, and process (Miles and Snow 1978).

The role of competitive intelligence in strategic activities

Generally, the role of competitive intelligence in business organizations can be classified into the following categories: (i) supporting strategic decision making (Prescott and Smith 1989); (ii) identifying early warning of threats and blind spots in business (Ghoshal and Westney 1991); (iii) supporting strategic planning and implementation for marketing, information technology and research and development activities (Vedder and Guynes 2002); (iv) supporting competitor assessment and tracking (Caudron 1994); and (v) performing industry benchmarking with competitors (Gelb et al. 1991).

Organizational strategy and competitive intelligence

The empirical studies conducted specifically on competitive intelligence are mostly descriptive in nature. Most studies profile the practices of competitive intelligence in organization across different countries. Almost all of the studies do not provide empirical evidence on the relationships between competitive intelligence and its antecedents and consequences. There is even lesser empirical research examining the relationship between organizational strategy and competitive intelligence practices. On the other hand, literature on environmental scanning, the sister field of competitive intelligence, is considered more established. Environmental scanning is defined as the acquisition of information about events, relationships, and trends in a company's external environment, the knowledge of which would assist top management in planning the company's future course of action (Aguilar 1967). According to Gilad (1989), the scope of environmental scanning is broader as competitive intelligence focuses on forces with which an organization transacts. Calof and Wright (2008), on the other hand, regard environmental scanning as the predecessor of competitive intelligence. Rouibah (2003) considered environmental scanning as another term of competitive intelligence along with early warning system, strategic watch and business intelligence. As such, the literature on environmental scanning is considered relevant to competitive intelligence research.

Reviews of the literature contend that competitive strategy affect the manners in which environment scanning activities were conducted. For instance, past studies adopted either Porter's (1980) competitive strategy model such as low cost leadership strategy and differentiation strategy (Jennings and Lumpkin 1992; Miller 1989; Raymond et al. 2001), or Miles's and Snow's (1978) strategic typology such as prospector, defender, analyser, and reactor (Beal 2000; Cartwright et al.1995; Hambrick 1982; Miller 1988), or combination of the two (Parnell 1997, 2000).

Miller (1989) examined the relationship between Porter's competitive strategies and strategy making process, including systematic scanning of the environments, in ninety-eight Canadian firms. He found that innovative differentiation strategy is significantly associated with all strategy making variables, including scanning activities which track technological developments and anticipate competitor and customer reactions to new products. Particularly, this relationship is more obvious among the successful companies, as measured by perceptual long run profitability and its growth. On the contrary, cost leadership strategy performed very little scanning and market analysis. Cost leadership allowed only information processing that contributes to internal efficiency such as cost analysis and scanning for more efficient method of production. Cost leadership's simplicity and economy discouraged costly information processing in scanning and analysis of customer preferences, competitors' innovations, and new market opportunities. A similar relationship was found in focus strategy where the relative simplicity of administrative task did not require much information processing in the form of environmental scanning. Spontaneous reactions and rules of thumb may suffice in the focus strategy.

Jennings and Lumpkin (1992) studied the relationships between environmental scanning activities and the strategy adopted by companies of forty-four chief executives from savings and loan industry through telephone interviews. The study adopted Porter's generic strategies of leadership and differentiation, and opportunities and threats as the dimensions of scanning activities. They found a significant difference between strategies adopted by companies and environmental scanning activities, specifically, organizations with a differentiation strategy engaged in environmental scanning focusing on opportunities and customers' attitudes evaluation while cost leadership strategy focuses on evaluation of threats from competitors and regulators. The finding was consistent with Miller's (1989) and was later supported by the studies of Hagen and Amin (1995) and Hagen et al. (2003) using samples from Egypt and Jordan and by that of Kumar et al. (2001) using a hospital sample.

Subramanian et al. (1993) examined the link between strategy and environmental scanning in sixty-eight Fortune 500 manufacturing firms. By using Miles's and Snow's (1978) strategic typology and Jain's (1984) environmental scanning phases in terms of its scope, depth, and focus, they found that the scanning systems used by an organization vary depending on its strategic orientation, in which prospectors implemented the most advanced scanning systems, followed by analysers and defenders.

Cartwright et al. (1995) surveyed seventy-four companies, which are members of the SCIP (Strategic and Competitive Intelligence Professionals). The study examined whether a relationship exists between perceived competitive intelligence usefulness in strategic decision making and strategic orientation of the firms and specific characteristics of competitive intelligence. The study found that technical adequacy (quality) and interaction with the competitive intelligence unit are the major characteristics influencing the perceived usefulness of competitive intelligence. Project-based competitive intelligence tends to be perceived useful regardless of strategic orientation of the firm. However, continuous competitive intelligence, both comprehensive and focus, was perceived differently by firms based on their strategic orientation. Prospectors and analysers perceived these comprehensive types of competitive intelligence as more useful than did defenders and reactors.

Walters and Priem (1999) investigated the relationship between business-level strategy and scanning activities among chief executive officers of 116 single-business manufacturing firms. In addition to information collected through survey, an experiment in a field setting was also conducted wherein chief executive officers responded in their offices to interactive, computer-delivered information search task. The study found that business-level strategy was related to the focus of scanning activities; specifically the differentiators emphasised external opportunities and thus collected information on market and technological sectors. On the other hand, cost leaders focused more on internal capabilities and thus placed more emphasis on political, legal and economic sectors. The high performing firms matched the external and internal scanning practices to their business-level strategy.

Kumar et al. (2001) examined the relationship between strategy and scanning as well as the moderating role of scanning in the strategy- performance relationship in the health care industry. Data were collected from 159 chief executives of the hospitals listed on the American Hospital Association Guide. The sample was heterogeneous in terms of profit orientation, size, location, age, and ownership. Based on variables developed by Jennings and Lumpkin (1992),the study found that differentiators focused on environmental scanning activities regarding opportunities. On the other hand, cost leaders tended to focus on collecting information regarding threats. organizational performance as measured by return in new services, success in retaining customers, profit margin and success in controlling cost was found to be higher in hospitals which are able to align their environmental scanning focus and competitive strategy.

Walters et al. (2005) examined the link between the business-level strategy and scanning practices and internal firm characteristics of eighty-six small manufacturing firms. The study found that the scanning practices of firms are dependant on the strategy adopted. In terms of internal scanning efforts, managers pursuing a cost leadership strategy emphasised on cost control but managers pursuing a differentiator strategy emphasised on product research and development, market research and basic engineering. In terms of scanning effort in external environment sectors, differentiators placed more emphasis on market sector. However, firms pursuing either strategy are required to have a challenging balancing act to perform their scanning activities in order to achieve success.

The above review illustrates the link between organizational strategy and competitive intelligence practices. The following hypotheses were proposed for this study:

Hypothesis 1: The amount of competitive intelligence acquisition varies across strategy types.

Hypothesis 2: The extent of competitive intelligence use in strategic decision making varies across strategy types.

Methods

Sample and procedures

The study sample was taken from companies listed on Bursa Malaysia in light of the belief that larger companies would have a higher possibility of having a formal competitive intelligence unit as compared to smaller firms and larger companies tend to be listed companies. One thousand companies were listed on Bursa Malaysia (formally Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange) as at end of 2007, of which 640 on the Main Board, 234 on the Second Board, and 126 on the MESDAQ market. The final sample excludes those divisions or units of conglomerates or subsidiary companies where competitive intelligence practices may be inherited from the main companies. Similarly, all the holding companies are excluded as they do not conduct any business activities. A search from the website, which includes Bursa Malaysia and individual company's websites was conducted to obtain the corresponding address of each sample. Finally, a total of 900 companies was selected as the targeted samples in this study.

Of the 900 questionnaire forms sent out, ninety-three were returned

with complete and usable data, a response rate of 10.3%. The

respondents consists of companies from various industry categories.

Trading and service, finance, and industrial product categories

represent half of the total respondents (50%). In terms of

organizational size measured by total number of employee, the largest

company has more than 30,000 employees, while the smallest company has

less than fifty employees. The mean is 2,538 with a standard deviation

of 5,613. A median of 500 was computed for additional information. The

questionnaire was completed by departmental manager (40%), followed by

vice president, general manager, divisional director or chief operating

officer (33%), and chief executive officer or managing director (27%). Analyser is the strategic typology mostly pursued by the sample (45%), followed by defender (26%). Meanwhile, the remaining sample is about equally distributed between prospector (15%) and reactor (14%).

In order to check the representativeness of the respondents, the distributions of organization by industry category in the respondents and sampled companies are compared. For the industry category, the deviations between the sampled companies and respondents are less than ±6%, with an exception for Finance category, where the deviation is -8%. Since almost all deviations are within ±6% range (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000), the study suggested that the respondents are representative of the sampled companies.

As the response rate for the study was considered low, it might have the possibility that respondents and non-respondents may differ in some significant manner. Due to the difficulty associated with the identification of non-respondents’ characteristics in an anonymous research, a wave analysis of non-response bias was conducted (Rogelberg & Stanton, 2007). The procedure involves comparing early respondents whose survey forms were received within one month and late respondents whose survey forms were received after a month. In this study, there are 55 responses that can be classified as early respondents and 42 as late respondents. Using independent sample t test, the results show no significant difference between early and late respondents on competitive intelligence acquisition and use. Since late responses proxy non-responses, it can therefore be suggested that non-response bias will not seriously affect the generalisability of the study findings.

| Industry | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer products | 14 | 5.1 |

| Industrial products | 15 | 16.1 |

| Construction | 7 | 7.5 |

| Trading and services | 17 | 18.3 |

| Finance | 15 | 16.1 |

| Technology | 8 | 8.6 |

| Properties | 7 | 7.5 |

| Plantation | 6 | 6.5 |

| Others | 4 | 4.3 |

| Size (No. of employees) | ||

| Below 200 | 20 | 21.5 |

| 200-499 | 24 | 25.8 |

| 500-999 | 14 | 15.1 |

| 1,000-2,999 | 19 | 20.4 |

| 3,000 and above | 16 | 17.2 |

| Position | ||

| Chief executive or managing director | 25 | 26.9 |

| Vice president, general manager, chief operating officer, or director | 31 | 33.3 |

| Departmental manager | 37 | 39.8 |

| Organizational strategy | ||

| Defender | 24 | 25.8 |

| Prospector | 14 | 15.1 |

| Analyser | 42 | 45.1 |

| Reactor | 13 | 14.0 |

| Industry | Respondents | Sampled companies | Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer products | 15% | 13% | -2% |

| Industrial products | 16% | 22% | 6% |

| Construction | 8% | 7% | -1% |

| Trading & services | 18% | 23% | 5% |

| Finance | 16% | 8% | -8% |

| Technology | 9% | 3% | -6% |

| Properties | 8% | 14% | 6% |

| Plantation | 7% | 7% | — |

| Others | 4% | 5% | 1% |

Variables and measurement

Organizational strategy

The study adopts the strategic typology of Miles and Snow (1978) because: (1) it is based on empirical evidence in a cross-section of industries; (2) it is parsimonious for identification of strategic typologies within a variety of industries; (3) it has made explicit relationships that might exist between strategy typologies and scanning activities, which is related to competitive intelligence practices; (4) it has been extensively applied in the strategy literature and has been found consistently and strongly supported in different industries, including hospitals, colleges, banking, industrial products, and life insurance (Hambrick 1983; McKee et al. 1989; Shortell and Zajac 1990).

Conant et al. (1990) developed an instrument that considers each of the elevan adaptive cycles originally proposed by Miles and Snow. This instrument is considered to be more appropriate compared to other instruments as it is multi-item scale covering each of the dimensions with scale consistency and useful for large samples. Each of the eleven items consists of four responses representing each of the four strategy types. In determining which type of strategy typology is adopted by the organizations, a majority-rule decision structure is applied. Thus, organizations are classified as defenders, prospectors, analysers or reactors based on the archetypal response option that is selected most often. In the case of ties between defender, prospector and/or analyser response options will result in the organization being classified as an analyser, while any tie involving reactor response options will result in the organization being classified as a reactor (Conant et al. 1990). This instrument has been tested as reliable and valid in many strategy studies (e.g., DeSarbo et al. 2005; Dyer and Song 1997; Parnell and Wright 1993 ).

Competitive intelligence practices

Competitive intelligence practice is conceptualised as having two dimensions; acquisition and strategic use. For competitive intelligence acquisition, respondents answer two questions based on the perceived importance of acquiring competitive intelligence and the frequency of competitive intelligence acquisition. The type of competitive intelligence is classified based on both internal and external business environmental sectors which include customer, competitor, supplier, technology, regulatory, socio-cultural, economic, human resource, global, and organization (Daft et al. 1988 ). The perceived importance of each competitive intelligence type is measured along a five-point scale from 1 - not important to 5 - very important. The frequency of competitive intelligence acquisition is measured using a five-point scale from 1 - very low to 5 - very high. The measurement scale and the phrasing of the questions were adopted from Choo (1993) who measured the amount of environmental scanning by chief executive officers. An index for the amount of competitive intelligence acquisition is computed by multiplying the acquisition frequency of competitive intelligence and the perceived importance ascribed to each type of competitive intelligence.

For competitive intelligence strategic use, respondents answer two questions based on the perceived importance of each strategic decision in their organization, and the frequency of competitive intelligence use in strategic decision making. Dess and Robinson (1984) define strategic decisions as having a significant impact on the future state of the firm and/or resulting in the commitment of large amounts of organizational resources. It is exemplified by development of new products and purchase of major equipment. It is vital to note that types of decisions that are strategic in one industry may be less so in another (Hickson et al. 1986) and the categories do overlap. Again, there is no universally accepted way of classifying strategic decisions; the study selects eleven strategic decisions which are adopted from the studies of Mintzberg et al. (1976), Dean and Sharfman (1996), and Culver (2006). The strategic decisions selected are merger and acquisition; strategic alliance and joint venture; market entry or exit; vertical integration; capacity expansion; new product and service development; diversification; divestment or divestiture; technology adoption; global; and organization. The perceived importance of each strategic decision is measured along a five-point scale from 1 - not important to 5 - very important. The frequency of competitive intelligence use in strategic decision making is measured using a five-point scale from 1 - very low to 5 - very high. The measurement scale and the phrasing of the questions were adopted from Choo (1993) who measured the amount of information use in decision making by chief executive officers. Similar to competitive intelligence acquisition, an index for the extent of competitive intelligence use in strategic decision making is computed by multiplying the use frequency of competitive intelligence and the perceived importance ascribed to each strategic decision.

Results and discussion

Descriptive analysis

The amount of competitive intelligence acquisition is computed by multiplying the perceived importance of competitive intelligence acquisition and frequency of competitive intelligence acquisition. The ranking of the amount of competitive intelligence acquisition is similar to that of the frequency, in which customer is ranked first, followed by competitor, economic and global and technological. Meanwhile, the amount of competitive intelligence acquisition is lowest for socio-cultural and human resources. In most cases, the frequency of acquiring competitive intelligence from a sector is consistent with the perceived importance of that sector, in which the higher the perceived importance of the sector, the higher the frequency of acquiring competitive intelligence from the sector.

The extent of competitive intelligence strategic use is computed by multiplying the perceived importance of strategic decision and frequency of competitive intelligence use in strategic decision making. The sampled companies use competitive intelligence in the greatest extent when making decision concerning new products and services development, followed by capacity expansion, strategic alliance, and market entry or exit. Meanwhile, competitive intelligence is least used in making decision about divestment and vertical integration. Similar to competitive intelligence acquisition, the frequency of using competitive intelligence in making strategic decision is consistent with the perceived importance of the type of decision, in which the higher the perceived importance of a strategic decision, the higher the frequency of using competitive intelligence in making that strategic decision.

| Perceived importance | Acquisition frequency | Amount of CI acquisition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of CI | M | SD | Rank | M | SD | Rank | M | SD | Rank |

| Customer | 4.43 | 0.69 | 1 | 2.96 | 1.06 | 1 | 13.23 | 5.43 | 1 |

| Competitor | 4.26 | 0.72 | 2 | 2.85 | 1.07 | 3 | 12.37 | 5.60 | 2 |

| Economic | 3.78 | 0.83 | 4 | 2.89 | 1.14 | 2 | 11.14 | 5.58 | 3 |

| Global | 3.67 | 0.86 | 6 | 2.73 | 1.15 | 4 | 10.33 | 5.48 | 4 |

| Technological | 3.86 | 0.88 | 3 | 2.45 | 0.98 | 7 | 9.70 | 4.97 | 5 |

| Supplier | 3.58 | 0.88 | 7 | 2.60 | 0.99 | 5 | 9.52 | 4.95 | 6 |

| Regulatory | 3.70 | 0.94 | 5 | 2.54 | 1.06 | 6 | 9.45 | 4.77 | 7 |

| organizational | 3.47 | 0.89 | 8 | 2.44 | 1.01 | 8 | 8.72 | 4.75 | 8 |

| Human Resources | 3.39 | 0.77 | 9 | 2.40 | 1.07 | 9 | 8.28 | 4.45 | 9 |

| Socio-cultural | 3.39 | 0.87 | 10 | 2.23 | 1.03 | 10 | 7.42 | 4.42 | 10 |

| Type of strategic decision | Perceived importance | Use frequency | Extent of CI use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Rank | M | SD | Rank | M | SD | Rank | |

| New product development | 4.04 | 0.81 | 3 | 3.95 | 0.91 | 1 | 16.29 | 5.82 | 1 |

| Capacity expansion | 4.05 | 0.86 | 3 | 3.90 | 0.97 | 2 | 16.25 | 6.36 | 2 |

| Strategic alliance | 4.08 | 0.88 | 1 | 3.78 | 1.06 | 3 | 16.04 | 6.71 | 3 |

| Market entry/exit | 3.82 | 0.96 | 4 | 3.66 | 1.04 | 4 | 14.59 | 6.51 | 4 |

| Technology adoption | 3.80 | 0.83 | 5 | 3.65 | 1.01 | 5 | 14.41 | 6.18 | 5 |

| Merger & acquisition | 3.54 | 1.22 | 10 | 3.43 | 1.26 | 7 | 13.31 | 7.80 | 6 |

| organizational | 3.61 | 0.87 | 7 | 3.47 | 0.90 | 6 | 13.07 | 5.61 | 7 |

| Global | 3.61 | 0.98 | 7 | 3.41 | 1.00 | 8 | 12.92 | 6.30 | 8 |

| Diversification | 3.48 | 0.99 | 6 | 3.30 | 1.01 | 11 | 12.87 | 6.17 | 9 |

| Vertical integration | 3.58 | 0.95 | 9 | 3.38 | 1.04 | 9 | 12.74 | 6.23 | 10 |

| Divestment | 3.22 | 1.09 | 11 | 3.34 | 1.11 | 10 | 11.45 | 6.23 | 11 |

Hypotheses testing

In testing the two hypotheses, prospectors and reactors are excluded as the sample size for both groups is below twenty. In addition, reactors have been excluded from the analysis in previous studies as they do not possess a consistent pattern of strategy (Matsuno and Mentzer 2000; Song et al. 2007). Independent sample t-test was used to test the difference in competitive intelligence practices between analysers and defenders. As shown in Table 5, the difference in the amount of competitive intelligence acquisition is higher among analysers and defenders in all ten sectors but only significant in two out of the ten sectors, namely the technology and economic sectors. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported by the data. It may be argued that, being the second mover in the market, analysers acquired significantly higher amount of the competitive intelligence from technology and economic sectors in order to exploit the technological opportunities and capitalise on changing economic conditions. One the other hand, the other environmental sectors are seen as important by all strategic typologies and, therefore, the amount of competitive intelligence acquisition is not significantly different between the two types.

Meanwhile, the significantly higher extent of competitive intelligence use is prevalent in eight out of 11 strategic decisions among the analysers as compared to the defenders. As shown in Table 6, the largest difference is found in technology adoption decision, followed by market entry/exit, strategic alliance, and new product/service development. On the other hand, no significant difference is found in decisions concerning diversification, divestment, and organisation. Similarly, Hypotheis 2 was also partially supported by the data. It may be argued in the way that strategic decision concerning organisation is viewed as important by both typologies, the extent of competitive intelligence use is thus insignificant between the two typologies. On the other hand, analysers are more aggressive in pursuing new product and service development as well as other expansion strategies, the extent of competitive intelligence use is significantly higher than the defenders.

| Type of competitive intelligence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defender (n=24) | Analyser (n=42) | Mean difference | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t-value | p-value | |

| Technology | 7.13 | 3.39 | 11.12 | 5.30 | 3.727 | 0.000 |

| Economic | 9.13 | 5.19 | 12.69 | 5.71 | 2.521 | 0.014 |

| Global | 8.75 | 5.80 | 11.48 | 5.05 | 1.998 | 0.050 |

| Socio-cultural | 5.83 | 4.48 | 8.02 | 4.43 | 1.926 | 0.059 |

| Human resources | 7.08 | 3.80 | 8.88 | 4.58 | 1.628 | 0.109 |

| Supplier | 8.63 | 3.50 | 10.21 | 5.47 | 1.438 | 0.155 |

| organization | 7.42 | 4.32 | 9.10 | 4.70 | 1.436 | 0.156 |

| Regulatory | 8.25 | 4.00 | 9.93 | 5.01 | 1.492 | 0.165 |

| Competitor | 11.91 | 6.19 | 13.00 | 5.47 | 0.731 | 0.467 |

| Customer | 12.92 | 4.34 | 13.64 | 5.57 | 0.549 | 0.585 |

| Type of strategic decision | Defender (n=24) | Analyser (n=42) | Mean difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t-value | p-value | |

| Techonolgy adoption | 10.88 | 5.74 | 15.45 | 5.13 | 3.341 | 0.001 |

| Market entry or exit | 11.63 | 6.50 | 16.21 | 5.86 | 2.941 | 0.005 |

| Strategic alliance | 13.21 | 7.34 | 17.64 | 5.58 | 2.764 | 0.007 |

| New product development | 13.83 | 5.65 | 17.76 | 5.47 | 2.774 | 0.007 |

| Merger and acquisition | 10.58 | 7.40 | 15.55 | 7.14 | 2.682 | 0.009 |

| Global | 10.17 | 5.66 | 13.91 | 5.72 | 2.564 | 0.013 |

| Vertical integration | 10.38 | 5.72 | 14.36 | 6.41 | 2.521 | 0.014 |

| Capacity expansion | 14.04 | 6.99 | 18.14 | 5.14 | 2.512 | 0.016 |

| Organizational | 11.42 | 5.91 | 13.79 | 4.61 | 1.809 | 0.075 |

| Divestment | 10.88 | 7.04 | 12.76 | 5.56 | 1.202 | 0.234 |

| Diversification | 12.33 | 6.77 | 14.00 | 5.07 | 1.136 | 0.260 |

Conclusion

The findings have implications on two perspectives: academic and managerial. For the academic perspective, this study serves as one of the earliest empirical studies to examine the relationship between organizational strategy and competitive intelligence practices. The findings of this study also confirm the link between organizational strategy and competitive intelligence practices in which a higher level of competitive intelligence acquisition in technological and economic sectors and a greater extent of competitive intelligence use in most of the strategic decision making is found among analysers. Business organizations that adopt the analyser strategy may wish to pay greater attention to issues and development trends of new technological changes and acquire a higher level of intelligence about this sector. As analysers emphasise capitalising on the innovativeness of new technology advancement, the higher level of technology intelligence acquisition enables managers to use technology intelligence in a greater extent when making strategic decisions pertaining to technology adoption.

The study also has implications for managers responsible for strategic decision making in organizations pursuing analyser typology. As competition in the global market intensifies and the pace of technological change accelerates, managers should initiate and organize competitive intelligence activities in their organization. Systematic acquisition of intelligence about the technology and economic sectors enables managers to better understand the business situation and enhance the quality of strategic decision making concerning technology adoption and market expansion. Business organizations may wish to design and implement a competitive intelligence system which is capable of systematically capturing intelligence from internal and external environments. The competitive intelligence system should be integrated with other enterprise-wide information systems in order to achieve long term benefits from the competitive intelligence efforts, specifically in enhancing the quality of strategic decision making. As competitive intelligence emphasises on actionable information as compared to other information management tools, whether the intelligence acquired is subsequently used in strategic decision making is of utmost importance. Therefore, business organizations must ensure that competitive intelligence systems will be able to provide intelligence to the right people at the right time so that it will be utilised in the relevant strategic decision making.

This study suffers from several limitations. The sample size of this study is below one hundred and represents only slightly over 10% of the population. As such, the findings of this study cannot be generalised across the Malaysian public listed companies, which practise formal competitive intelligence. Future studies are recommended to increase the sample size, specifically from the prospectors and reactors, so that comparison in terms of competitive intelligence practices among all strategy types will be feasible. This study also does not deal with all the activities of competitive intelligence cycle besides competitive intelligence acquisition and strategic use. It would be too ambitious to cover all the phases of competitive intelligence cycle for this study, and there is no doubt that the other phases of competitive intelligence cycle are also important. In order to capture the complete domain of competitive intelligence practices, future researchers are recommended to include intelligence planning, analysis, and dissemination apart from acquisition and strategic use as presented in this study. Future researchers are also recommended to include moderating variables such as industry category, business functions, and firm size as these variables may have some impact on the hypothesized relationship among the research constructs. When time permits, longitudinal research is recommended, especially in examining the causal or probable reciprocal relationship between organizational strategy and competitive intelligence practices. Functional mangers constitute the largest proportion in the sample (40%) of this study. Each functional manager may differ in the competitive intelligence practices, specifically the amount of competitive intelligence acquisition and the extent of competitive intelligence use in different decision making. As the functional managers may focus only on some particular sectors, some of the survey items may fall outside their task domain. Moreover, the study could not examine this difference due to limited responses from each business function.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Universiti Tun Abdul Razak's Research Grant.

About the authors

Ching Seng Yap

is an Assistant Professor in the Graduate School of Business,

Universiti Tun Abdul Razak, Malaysia. He received his Bachelor's degree

in Agribusiness and Master of Information Technology from Universiti

Putra Malaysia and his PhD in Management from Universiti Tun Abdul

Razak, Malaysia. He can be contacted at:chingseng@unirazak.edu.my

Md Zabid Abdul Rashid is Professor and President/Vice

Chancellor of Universiti Tun Abdul Razak. He received his Bachelor's

degree in Agribusiness from Universiti Putra Malaysia and his Master of

Science from University of London, UK and his DSc from

Aix-Marseilles/ESSEC, France. He can be contacted at: zabid@unirazak.edu.my

Dewi Amat Sapuan is an Associate Professor in the

Graduate School of Business, Universiti Tun Abdul Razak, Malaysia. She

received her Bachelor's degree in Business Administration from

Universiti Utara Malaysia and her Master of Business Administration

and PhD in Management from Universiti Tun Abdul Razak, Malaysia. She

can be contacted at: dewi@unirazak.edu.my