The role of perceived substitution and individual culture in the adoption of electronic newspapers in Scandinavia

Nicolai Pogrebnyakov and Mikael Buchmann

Copenhagen Business School, Porcelaenshaven 24, Frederiksberg 2000, Denmark

Introduction

The ongoing evolution of the Internet and portable devices has been dramatically changing the business of delivering news and analysis to readers. Established newspapers, some in existence for several centuries, have been challenged to adapt to new channels of content delivery and start updating their news stream constantly, instead of once or twice a day. At the same time newspapers have found themselves competing for readers with new media actors, such as blogs, microblogging platforms, content aggregators and social curation sites. The circulation of printed newspapers and magazines in most countries has been dwindling: for example, in the USA daily circulation of print newspapers fell by 30% from 1990 to 2010 (Edmonds, Guskin, Rosenstiel and Mitchell, 2012), although it was stable in 2012 (Edmonds, Guskin, Mitchell and Jurkowitz, 2013).

However, these trends are not uniform across countries. First, there have always been differences between countries in newspaper readership. Hallin and Mancini (2004) found important differences between newspapers in the Mediterranean, North and Central European, and North Atlantic countries, such as the level of partisan division and the level of state involvement in newspapers (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). Second, while print circulation is falling in much of the developed world, it has been rising in recent years in countries such as China, India, Mexico and Saudi Arabia (Kilman, 2012; The Economist, 2013).

Finally, digital and mobile technologies have to some extent compensated for falling print circulations. Mobile access is growing fast in developing countries, which accounted for 80% of new mobile subscriptions in 2011 (International Telecommunications Union, 2012). Many newspapers have seen subscribers switch from print to digital and mobile editions (Edmonds et al., 2013), although print subscriptions may be cannibalised by digital ones (Bleyen and Van Hove, 2011). Thus an increasing use of portable devices for content distribution reinforces the transition from print to digital. Access to media from devices is expected to overtake access from other platforms (Nielsen, 2012). Mobile Internet traffic has been more than doubling every year and is anticipated to continue to grow at similar rates in the following years (Cisco, 2012).

At the same time, many of the theories explaining technology adoption have focused on characteristics of the new technology and have largely omitted a comparison of the new technology with the one it is replacing. This comparison perspective is referred to as technology substitution (Norton and Bass, 1987) and has been widely studied in the media domain, where the focus has been on comparative characteristics of information dissemination media (radio, television etc.). This paper attempts to place the technology substitution perspective in conjunction with individual adopter characteristics.

Digital newspapers started to appear together with the broad adoption of the Internet in the 1990s. Two major trends emerged. First, established newspapers rolled out online editions, which were little more than a digitized print edition, providing a mix of news and analysis. Second, a new category of sites emerged that were not affiliated with newspapers. They tended to provide quick updates and breaking news (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010). Currently many newspapers maintain several digital formats: an e-reader edition formatted for viewing on devices such as Amazon’s Kindle and Apple’s iPad; a digital replica with the same content and layout as their print edition to be viewed on a desktop computer, and a Website which often offers more content. In 2011, for most of the top 25 US newspapers by circulation, the majority of subscriptions to a digital version were to the combined e-reader and digital replica editions, rather than to the Website (Edmonds et al., 2012).

The debate over whether the Internet has or will displace print newspapers has continued ever since. There is evidence that readers of online newspapers have significantly reduced their consumption of print newspapers but not ceased it completely (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010). Other research found that Internet-based and printed newspapers are in fact complementary. People who read more in one channel tend to read more in the other (Nguyen and Western, 2006) and increase the overall time spent on media consumption (Newell, Pilotta and Thomas, 2008). Interestingly, readers of print newspapers tend to have higher perceptions of credibility of online news than those who primarily use the Internet for entertainment (Stavrositu and Sundar, 2008).

Recently newspapers began introducing versions targeted specifically at portable readers with electronic paper displays (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010), such as Amazon’s Kindle Paperwhite. These devices rely on ambient light, similar to a printed page and unlike modern smartphone screens, which are backlit. This reduces eye fatigue (Jung, Chan-Olmsted, Park and Kim, 2012). Such displays are comparable to printed text for legibility (or perform even better, thanks to the ability to change font size), are superior in functionality (some feature audio or Internet browsing), but may be inferior in usability (e.g., often it is not immediately obvious how to change the text to landscape orientation) (Jung et al., 2012; Noyes and Garland, 2008; Siegenthaler, Wurtz and Groner, 2010). Despite that, e-readers have not displaced online or paper-based books (Gregory, 2008). Thus the transition to mobile digital content distribution of daily newspapers results in dramatic changes, including the emergence of new business models and the convergence of different media channels.

This paper focuses on the substitution of print newspapers with electronic ones. It investigates the following research question: is the transition from printed to electronic newspaper influenced by the comparative characteristics of these two media, by characteristics of individual adopters, or by both?

To address this research question this study builds on two theoretical perspectives. First, it applies the substitution perspective to a technological artefact, the electronic newspaper. This perspective compares the characteristics of the existing technology with those of a new one and strives to determine the relative benefits of adopting a new technology as opposed to continued use of the existing one. This perspective has received substantial attention in the media research realm. In particular this study investigates the comparative characteristics of electronic newspapers, the new technology, against print newspapers, the existing technology. Second, it compares the influence of artefact-specific factors to the impact of individual characteristics on adoption. Individual characteristics are conceptualized as cultural factors applied at the individual level of analysis and artefact factors describe the functionality of the technology, in this case electronic newspaper. This study explores any effect that these cultural characteristics might have on adoption.

We focus on Scandinavian countries, which have consistently been among the top ten worldwide for newspaper circulation (Kilman, 2012; UNESCO, 2014). A media culture common to these countries is characterized by relatively strong partisanship, high professional standards of journalists and limits on state power coupled with a tradition of public sector involvement in media stemming from the welfare states in these countries (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). This can be attributed to the historical development of newspapers in these countries, where Protestantism led to an early spread of literacy. Local patriotism, where readers were seeking local newspapers, even in small towns, also contributed to the development of a thriving newspaper culture. Scandinavian countries thus differ in important respects from North Atlantic countries such as the USA, Canada or the UK. In this liberal model newspapers tend to be politically neutral, owing to an early development of commercial newspapers which was not influenced by the state. Newspapers in Scandinavia are also different from those in the Mediterranean, where they are often viewed as a means of political mobilization (Hallin and Mancini, 2004).

Our contribution to existing research is twofold. First, this study informs and enriches existing studies of technology substitution and the effects of substitution on adoption. Second, it compares the relative importance of factors specific to the technology artefact over factors specific to individuals in technology adoption, thereby potentially identifying the degree of individual agency in adoption.

The paper is organized as follows: section two reviews extant literature and advances hypotheses; section three describes the methodology; section four presents the results; section five discusses these results and their implications; and section six concludes the paper.

Literature review and hypotheses

Perceived substitution

Technology substitution refers to the replacement of an existing artefact or technology with another, typically newer, artefact or technology (Norton and Bass, 1987). At the individual level, substitution may occur if the new technology offers greater benefits or higher perceived value compared to that of the previous one (Briggs, Nunamaker and Tobey, 2001; Dimmick, Chen and Li, 2004; Lin, 2001). Benefits may be tangible or intangible and include lower price, greater convenience, higher usability and greater flexibility (Lichtenstein and Williamson, 2006). Substitution may take place if benefits derived from the existing technology no longer meet existing needs of its users, when new user needs arise which the existing technology cannot meet, or when the existing technology is made obsolete by changes in the environment (Paap and Katz, 2004; Schmidt and Druehl, 2005).

Another important consideration is the cost of switching to the new artefact or technology. At the individual level these costs depend on the relative complexity of the new technology or the extent to which it is easier or harder to understand and handle compared to the old one. This relative complexity has been shown to be a good predictor of substitution (Tsai, Lee and Wu, 2010).

The replacement of an existing technology with a new one is not always complete. Sometimes the new technology replaces only part of the functionality of the existing one and the existing technology starts providing more specialized functions (Newell et al., 2008). For example, vinyl records, once a ubiquitous music listening technology, are now used only in niche areas, such as nightclubs. Furthermore, both the existing and the new technologies may change over time: e.g. their price may decrease or features may improve, perhaps in response to changes in customer needs (Schmidt and Druehl, 2005). Vinyl records provide a good example. The functionality of contemporary record players is very different from those used in the first half of the twentieth century because of advances in manufacturing and changes in their use.

Substitution may occur through several scenarios. In multi-generation technologies adopters may either skip one or more of the previous generations and leapfrog to the new generation, or adopt the generation that immediately follows the currently used one (Jiang and Jain, 2012).

Substitution is an underexplored research topic, in the sense that technology adoption studies often do not consider the extent of change between the old and new technologies (Xu, Venkatesh, Tam and Hong, 2010). At the same time, in many domains, particularly in mature markets, substitution is much more prevalent than initial adoption (Gordon, 2009). This topic has received more attention in the media domain, in studies of displacement of existing media by newer ones that provide similar functionality more easily or attractively (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010; Gaskins and Jerit, 2012). For example, research on the transition from print to online newspapers has highlighted the shift in control and gate-keeping from editors to readers. Because of the higher amount of content and hyperlinked articles online, these newspapers let the reader choose among suggested items to read, unlike print editions which offer editor-picked items to be read (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010). A similar argument is made for the substitution of radio with MP3 players. MP3 players allow the user to control what they listen to, unlike radio programming (Ferguson, Greer and Reardon, 2007).

Here, we primarily emphasize the technology aspect of electronic newspapers (and less so the content aspect). This drives our selection of variables in the model (e.g., perceived substitutive characteristics, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use of the technological artefact), as well as a discussion of the relationship between culture and technology adoption below. By contrast, if we chose to devote more attention to the content aspect of electronic newspapers, that would have called for more emphasis on communication frameworks. Further, the data collection effort was conducted in 2010, before mass adoption of electronic newspapers, particularly in the e-reader format. Therefore hypotheses test the intent to use electronic newspapers, rather than actual use.

At the same time, substitutive functionality and benefits of the new technology are sometimes based on subjective assessments of the customer and thus are not always rational (Briggs et al., 2001). We refer to these subjective substitution assessments as perceived substitution (Bijker, 1997; Blue, 2006; Morelli, 2003). An example of perceived substitution in the digital media realm is the change from video rentals on physical media (e.g., DVD) to streaming video on demand. The latter provides substitutive functionality of physical rentals (i.e., video content), with added functionality whose perceived benefits vary by user, such as wider title selection and faster availability of content.

Perceived substitution may affect expectations of the adoption of the new technology based on comparative characteristics of the existing and the new technologies. Thus we propose the following hypothesis:

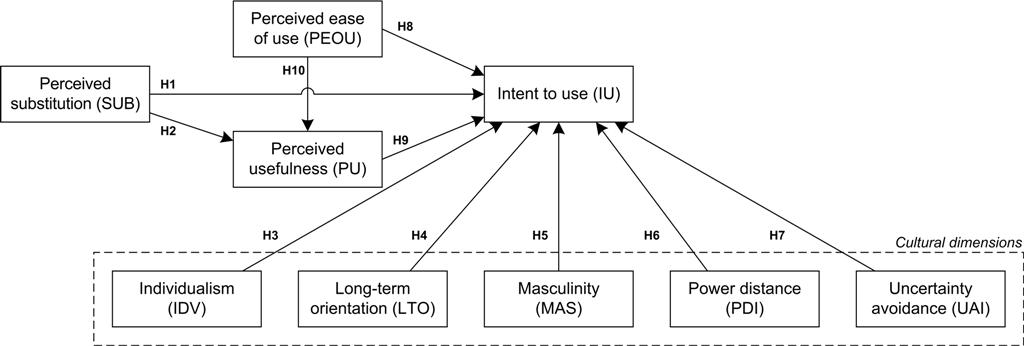

H1: Perceived substitution (SUB) characteristics of electronic newspapers have a positive effect on the intent to use (IU) electronic newspapers.

Further, the perceived substitution concept is different from perceived benefits of the new technology: unlike perceived benefits, perceived substitution considers both the existing and new technologies, as well as any gains from adoption compared to learning and other costs of adoption. Therefore perceived substitution may affect the perceived usefulness of the new technology. Thus we hypothesize:

H2: Perceived substitution (SUB) characteristics of electronic newspapers have a positive effect on perceived usefulness (PU) of electronic newspapers.

Culture and technology adoption

This study investigates the effect of culture at the individual level, since culture is a complex and multi-level construct that has been defined in a multitude of ways (Pogrebnyakov and Maitland, 2011). The basis of culture is assumptions, values and practices that are attributable to an individual or shared within a group or country (Lee, Choi, Kim and Hong, 2007; Taras, Rowney and Steel, 2009). These assumptions and values have an impact on the behaviour of individuals (DiMaggio, 1997), including behaviour related to the adoption or use of a particular technology (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Leidner and Kayworth, 2006). Specifically within the technology adoption realm, cultural factors have been shown to influence technology adoption both directly (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Lee et al., 2007) and as moderators (McCoy, Galletta and King, 2007; Srite and Karahanna, 2006; Yoon, 2009).

Several authors have stressed the importance of investigating culture at the individual level when studying technology adoption (Lee et al., 2007; Lee, Kim, Choi and Hong, 2010; Li, Hess, McNab and Yu, 2009). While many studies operationalize culture as a country-level factor, others point out that national-level culture is necessarily an average of cultural characteristics and will not describe well the culture of each individual in that country (Lee et al., 2007; Macfadyen, 2011). Therefore cultural profiles of countries are poor substitutes for individual cultural characteristics. In particular, individual technology adoption behaviour will vary between individuals and will likely be influenced by individual cultural traits.

We address this methodological and conceptual consideration by following the approach adopted by Srite and Karahanna (2006) and Yoon (2009) and measuring cultural dimensions at the individual level through a series of questions. We focus on five commonly used cultural dimensions: individualism, long-term orientation, masculinity, power distance and uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, 2001; Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, 1998). These dimensions were chosen for two reasons. First, they are the most widely used cultural factors among researchers (Taras et al., 2009). These dimensions are also present in many other commonly used operationalizations of culture (Taraset al., 2009), such as those of Hofstede (2001), Schwartz (1994) and Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998). Second, as a result they have been used in a wide variety of contexts, including technology adoption (Yoon, 2009). Following the approach of Yoon (2009) and Lee et al. (2007) among others, we measure cultural factors at the individual level. In the following we discuss each of the five cultural dimensions, their potential influence on adoption and their proposed influence on the intent to use electronic newspapers.

Individualism (IDV) reflects the extent to which individuals make their own choices as opposed to relying on opinions and norms of the group in decision-making (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Zakour, 2004). In technology adoption in particular, people with individualist inclinations tend to focus on their own goals and satisfaction, rather than those of the group or society (Lee et al., 2007). Therefore higher individualism is associated with greater rates of adoption of new technologies (Van Everdingen and Waarts, 2003). Further, the relationship between technology and individualism is two-directional, as information and communication technologies may themselves amplify individualistic behaviour (Straub, Keil and Brenner, 1997).

Given these arguments, higher individualism can be expected to be positively associated with the adoption of electronic newspapers. Since electronic newspapers are individual technology artefacts, their adoption is likely to be driven by individual utilitarian or hedonic considerations, rather than collective norms. Therefore we hypothesize:

H3: Individualism (IDV) has a positive effect on intent to use (IU) electronic newspapers.

Long-term orientation (LTO) describes whether individuals value tradition and are oriented towards longer-term payoffs, perhaps at the cost of shorter-term losses (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Taras et al., 2009; Veiga, Floyd and Dechant, 2001; Yoon, 2009). As such, this dimension deals with subjects such as perseverance, thrift, traditions and how people relate to them. Greater long-term orientation places more emphasis on established patterns of behaviour and thus is less likely to be conducive to adoption of new technologies, which often change established behaviour patterns (Erumban and de Jong, 2006). Further, the short-term changes in routines and practices that often accompany the adoption of new technologies may cause individuals with greater long-term orientation to see new technologies themselves as inappropriate. This is likely to cause the rejection of new technologies (Veiga et al., 2001).

This reasoning suggests that greater long-term orientation is likely to be detrimental to the adoption of electronic newspapers and it leads us to the following hypothesis:

H4: Long-term orientation (LTO) has a negative effect on the intent to use (IU) electronic newspapers.

Masculinity (MAS) entails personal traits such as the willingness to achieve one’s goals, higher self-confidence and materiality (Hofstede, 2001; Zakour, 2004). The opposite set of traits, femininity, puts more value on opinions of others and on achieving consensus with others (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Zakour, 2004). Because of their greater focus on materiality individuals with higher masculinity scores can be expected to place more value on technological artefacts. Further, such individuals may be more confident that they will be able to use a new technology to their advantage (McCoy et al., 2007; Van Everdingen and Waarts, 2003). At the organizational level, Hofstede (2001) indicated that higher masculinity is associated with higher innovativeness of organizations.

This reasoning suggests that higher masculinity is likely to be associated with higher degrees of adoption of electronic newspapers. This gives rise to the following hypothesis:

H5: Masculinity (MAS) has a positive effect on the intent to use (IU) electronic newspapers.

Power distance (PDI) describes the extent to which people accept that power is distributed unequally within a group or a society (Taras et al., 2009). Higher power distance often implies the reliance on formal rules and the existence of hierarchical and centralized decision structures (Erumban and de Jong, 2006). Individuals in higher power-distance settings are less likely to experiment with new technologies. This is because such technologies do not have a precedent and are less likely to be mandated by superiors, and therefore such experimentation would require significant autonomous decision-making. Furthermore, new technologies may facilitate information exchange between members of a group or society, independent of their formal position in the hierarchy. Therefore groups with lower power distance would naturally be more conducive to adopting new technologies (Zakour, 2004).

To sum up, power distance and technology adoption appear to be inversely related. Empirical research corroborates this reasoning: higher power-distance scores were found to have a negative relationship with the adoption of innovations both at the national level (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Van Everdingen and Waarts, 2003) and at the individual level (Shane, 1993). Thus we hypothesize:

H6: Power distance (PDI) has a negative effect on the intent to use (IU) electronic newspapers.

Uncertainty avoidance (UAI) reflects the degree to which individuals prefer explicit rules that guide their behaviour (Taras et al., 2009). Individuals with high uncertainty avoidance are likely to feel uncomfortable in uncertain situations and be threatened by ambiguity (Erumban and de Jong, 2006; Yoon, 2009). Since adoption of new technology often involves high degrees of ambiguity, individuals with higher uncertainty avoidance may be less likely to adopt new technologies (Zakour, 2004). At the organizational level, adoption of innovations is less likely in organizations with greater uncertainty avoidance, which often have innovation-constraining rules (Hofstede, 2001). Societies with high uncertainty avoidance have slower adoption rates for innovations, thus uncertainty avoidance is the most important cultural variable when examining adoption rates for innovations (Shane, 1993). Further, societies with high uncertainty avoidance scores are less open to change (Hofstede, 2001). It has been suggested that this reluctance might manifest itself in an inherent opposition to new technology and thus have a negative impact on the intent to use (Png, Tan and Wee, 2001; Straub et al., 1997).

Thus extant literature reveals an inverse relationship between uncertainty avoidance and technology adoption at individual, organizational and national levels of analysis. Therefore we hypothesize:

H7: Uncertainty avoidance (UAI) has a negative effect on the intent to use (IU) electronic newspapers.

Previous studies have found that the intention to use new technology is positively associated with the absence of effort required to familiarize oneself with the functionality of the technology (perceived ease of use) and with the individual’s evaluation of the utility of the technology (perceived usefulness) (Gefen, Karahanna and Straub, 2003; Yoon, 2009). Note that perceived usefulness is a measure of absolute utility of the technology, rather than a comparison with another technology with similar functionality. This makes it distinct from perceived substitution, which focuses on differences in functionality between existing and new technologies. Therefore we propose the following:

H8: Perceived ease of use (PEOU) of electronic newspapers has a positive effect on the intent to use (IU) them.

H9: Perceived usefulness (PU) of electronic newspapers has a positive effect on the intent to use (IU) them.

Finally, and also in line with previous research, because an easier to use technology is expected to be more useful (Gefen and Straub, 2000), the following hypothesis is proposed:

H10: Perceived ease of use (PEOU) of electronic newspapers has a positive effect on their perceived usefulness (PU).

The discussion above gives rise to the conceptual model shown in Figure 1.

Method

Data collection

A nationally representative sample for Denmark, Norway and Sweden (combined population 19.8 million in 2010 (World Bank, 2014)), was created based on age, sex and geographic location. These variables were included in the sample to achieve representativeness and control for distribution of responses across specific age groups, geographic locations and sex. Three age groups were used: 18 to 34 years, 35 to 49 years and 50 years and older. Both sexes were included in equal proportions. For the purposes of this research, the three countries were divided into geographic regions to properly reflect the distribution of the population in these countries. Denmark was divided into two regions: eastern and western. Norway was divided into two regions: eastern region and other geographic areas. Sweden included three regions: Götaland, Norrland and Svealand. This division of geographic areas ensured a mix of urban as well as rural populations, as well as respondents with varied backgrounds both economically and educationally.

The original questionnaire was created in Norwegian. It was pilot tested on a selection of individuals with knowledge of the media industry, technology industry and those who did not have an interest or background in either. Pilot testing resulted in minor changes, primarily semantic ones. The completed Norwegian original was then sent to native Danish and Swedish speakers, and after translation subsequently sent to a second native speaker for evaluation. A few minor changes were made in the second revision. No full pilot testing was done for the Swedish and Danish versions. Since the languages are sufficiently similar in the written form we also reviewed the final questionnaires in each language before they were sent out to respondents. No changes were made at this point.

The final questionnaire contained seventy-three questions, however certain questions were only asked of certain respondents. For example, when a respondent identified themself as a student or an employee, they were directed to questions about their background that were relevant for them, such as the course of study for students or the type of industry and position for employees.

Electronic links to the questionnaire were e-mailed to prospective respondents and the survey was delivered online. An online only version of the survey was justified because Internet penetration in the three countries in 2011 was 90%, well above the 69.6% average for the European Union and European Economic Area (Eurostat, 2012).

Questionnaire items for perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and intent to use were constructed following past research (Lu, Yu, Liu and Yao, 2003; Srite and Karahanna, 2006; Yoon, 2009). Questions for the cultural constructs (power-distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance and long-term orientation) were modelled on those used by Yoon (2009). Perceived substitution (SUB) questions were constructed de novo based on the literature on substitution.

A total of 1804 completed responses was received. The total number of respondents was 594 in Norway (90.6% response rate), 601 in Sweden (91.2%) and 609 in Denmark (85.6%). To probe for systematic differences between responders and non-responders we performed t-tests on age and sex between the two groups but did not find significant differences.

Path modelling

The data in this study were analysed with partial least squares regression). Partial least squares is a type of structural equation modelling. There are two ways of conducting structural equation modelling, namely covariance-based techniques such as LISREL, and variance-based techniques. Partial least squares is gaining popularity within many different disciplines and has been the foundation for numerous recent publications (Henseler, Ringle and Sinkovics, 2009). It is regarded as particularly useful when investigating descriptive and predictive relationships (Sellin and Keeves, 1997). We used SmartPLS to analyse the data (Ringle, Wende and Will, 2005).

We followed a two-step procedure described in Annear and Yates (2010). First, to avoid making generalizations based on incorrect premises, the unidimensionality of the reflective measures must be assessed. As described in Gefen (2003), the unidimensionality of each latent construct is assumed to exist only a priori and cannot be measured directly with partial least squares. Instead, what is measured is the discriminant and convergent validity of the reflective measures. Together they make up what is known as factorial validity, describing how well the measurement items relate to the latent constructs.

Second, after factorial validity had been confirmed, we examined and interpreted the path coefficients in the model. The path coefficients are created by the bootstrapping procedure which presents the paths in t-test values (Annear and Yates, 2010), which allows for straightforward analysis.

Factorial validity

Factorial validity demonstrates that measurement items comprising each factor (e.g., IDV1, IDV2) are related to only one of the factors (IDV). Establishment of factorial validity consists of two parts: convergent validity and discriminant validity (Gefen and Straub, 2005).

Discriminant validity is one part required in demonstrating factorial validity. The analysis is a combination of two factors and its purpose is to ensure that the measurement items can be statistically separated from each other (i.e. that they do not measure the same concept) (Gefen and Straub, 2005; Hulland, 1999). First, measurement items should load highly on the factor that has been theorized to include that item but not on other factors, and the correlation of the latent variable scores with the measurement items should reflect this pattern of loadings (Gefen and Straub, 2005). There is no clear consensus on how large the differences in loadings should be, but according to Gefen and Straub (2005) there should be a 0.1 difference between the loadings of the construct in question compared with loadings on all the measurement items on any other construct (i.e. if IDV1, 2 and 3 have loadings in the range of 0.7–0.9, no other measurement item should be higher than 0.6 on the same construct). As seen in Table 1, the results of confirmatory factor analysis conform to that requirement. All measurement items have much higher loadings on their own factor than on the other constructs.

| IDV | LTO | MAS | PDI | UAI | PEOU | PU | SUB | IU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDV | IDV1 | 0.892 | 0.636 | 0.532 | 0.578 | 0.506 | 0.499 | 0.473 | 0.541 | 0.445 |

| IDV2 | 0.853 | 0.609 | 0.594 | 0.436 | 0.451 | 0.435 | 0.430 | 0.463 | 0.385 | |

| LTO | LTO1 | 0.622 | 0.840 | 0.484 | 0.538 | 0.450 | 0.451 | 0.433 | 0.500 | 0.373 |

| LTO2 | 0.679 | 0.912 | 0.524 | 0.644 | 0.552 | 0.547 | 0.526 | 0.594 | 0.482 | |

| LTO3 | 0.567 | 0.868 | 0.425 | 0.618 | 0.435 | 0.485 | 0.473 | 0.516 | 0.420 | |

| MAS | MAS1 | 0.548 | 0.475 | 0.850 | 0.357 | 0.427 | 0.376 | 0.377 | 0.412 | 0.350 |

| MAS2 | 0.491 | 0.452 | 0.821 | 0.375 | 0.385 | 0.360 | 0.380 | 0.411 | 0.342 | |

| MAS3 | 0.570 | 0.448 | 0.840 | 0.321 | 0.433 | 0.377 | 0.390 | 0.423 | 0.360 | |

| PDI | PDI1 | 0.500 | 0.589 | 0.374 | 0.918 | 0.512 | 0.442 | 0.461 | 0.499 | 0.403 |

| PDI2 | 0.582 | 0.683 | 0.402 | 0.937 | 0.568 | 0.545 | 0.510 | 0.592 | 0.458 | |

| UAI | UAI1 | 0.507 | 0.514 | 0.456 | 0.544 | 0.937 | 0.427 | 0.390 | 0.476 | 0.381 |

| UAI2 | 0.525 | 0.522 | 0.475 | 0.552 | 0.943 | 0.459 | 0.434 | 0.522 | 0.399 | |

| PEOU | PEOU1 | 0.508 | 0.519 | 0.419 | 0.494 | 0.440 | 0.951 | 0.676 | 0.691 | 0.764 |

| PEOU2 | 0.506 | 0.534 | 0.413 | 0.505 | 0.452 | 0.955 | 0.637 | 0.679 | 0.703 | |

| PEOU3 | 0.499 | 0.551 | 0.417 | 0.510 | 0.438 | 0.909 | 0.592 | 0.668 | 0.651 | |

| PU | PU1 | 0.486 | 0.513 | 0.433 | 0.495 | 0.396 | 0.629 | 0.923 | 0.663 | 0.709 |

| PU2 | 0.475 | 0.505 | 0.415 | 0.478 | 0.417 | 0.630 | 0.932 | 0.670 | 0.778 | |

| SUB | SUB1 | 0.508 | 0.526 | 0.442 | 0.512 | 0.463 | 0.626 | 0.683 | 0.915 | 0.686 |

| SUB2 | 0.540 | 0.594 | 0.457 | 0.560 | 0.502 | 0.687 | 0.617 | 0.896 | 0.623 | |

| IU | IU1 | 0.449 | 0.465 | 0.398 | 0.454 | 0.400 | 0.642 | 0.763 | 0.696 | 0.930 |

| IU2 | 0.440 | 0.449 | 0.383 | 0.416 | 0.375 | 0.763 | 0.735 | 0.656 | 0.935 | |

Second, an analysis of the average variance extracted must be performed. Gefen and Straub (2005) proposed the following rule of thumb: the square root of the average variance extracted of each latent construct should be at least 0.5, and it should be much larger than the correlation of that construct with any other construct in the model. The correlation matrix, average variance extracted and composite construct reliability are shown in Table 2.

| IDV | LTO | MAS | PDI | UAI | PEOU | PU | SUB | IU | Construct reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDV | (0.873) | 0.865 | ||||||||

| LTO | 0.714 | (0.874) | 0.906 | |||||||

| MAS | 0.641 | 0.547 | (0.837) | 0.876 | ||||||

| PDI | 0.585 | 0.689 | 0.419 | (0.928) | 0.925 | |||||

| UAI | 0.549 | 0.551 | 0.496 | 0.583 | (0.940) | 0.938 | ||||

| PEOU | 0.537 | 0.568 | 0.443 | 0.535 | 0.472 | (0.939) | 0.957 | |||

| PU | 0.518 | 0.549 | 0.457 | 0.525 | 0.439 | 0.678 | (0.927) | 0.925 | ||

| SUB | 0.577 | 0.616 | 0.496 | 0.590 | 0.532 | 0.723 | 0.719 | (0.905) | 0.901 | |

| IU | 0.477 | 0.490 | 0.419 | 0.466 | 0.415 | 0.755 | 0.803 | 0.725 | (0.932) | 0.930 |

As shown in Table 2, all constructs satisfy the average variance extracted requirement stated above. The square root of the average variance extracted ranges from 0.837 for masculinity to 0.940 for uncertainty avoidance, which is significantly higher than the recommended value of 0.5. The square root of the average variance extracted is also higher than the correlation coefficient of the construct with the other constructs for all latent constructs.

Convergent validity is the other part that completes factorial validity. The condition of convergent validity is a significant (at least at 0.05 level) t-value loading of each measurement item on its latent construct (Gefen and Straub, 2005). Moreover, it is possible to look at composite reliability which is computed directly in SmartPLS. A construct shows acceptable convergent validity if this score is greater than 0.7 (Hulland, 1999). The results of confirmatory factor analysis show that all constructs have acceptable item reliability. Table 2 shows composite construct reliability, which ranged from 0.865 for individualism to 0.957 for perceived ease of use. These values are higher than the suggested value of 0.7 (Yoon, 2009). Therefore measured factors exhibit acceptable levels of construct reliability.

Results

Factor reliability as well as tests for convergent and discriminant validity were conducted. As a result, some items were dropped from the cultural, technology acceptance and substitution factors.

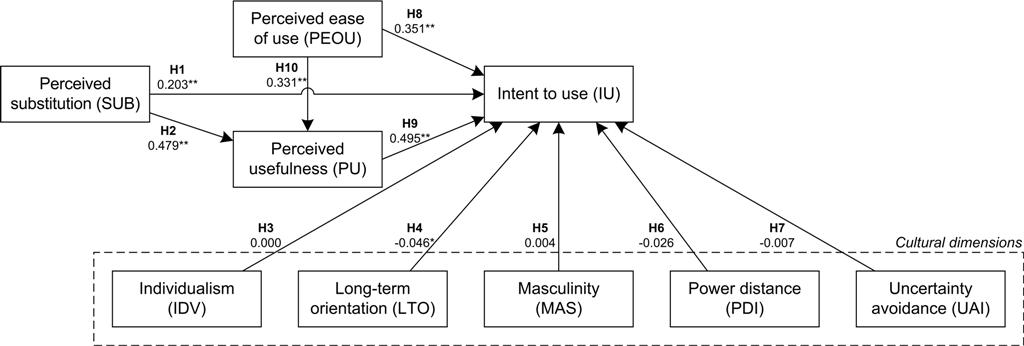

The research model with path coefficients estimates is shown in Figure 2.

Results of model estimation are shown in Table 3. The results suggest that the influence of perceived substitution on adoption constructs, including the intent to use, is statistically significant while the influence of most cultural dimensions is not.

| Hypothesis and path | Coefficient (t-value) |

|---|---|

| H1: SUB → IU | 0.203 (6.572)** |

| H2: SUB → PU | 0.479 (15.839)** |

| H3: IDV → IU | 0.000 (0.011) |

| H4: LTO → IU | -0.046 (1.983)* |

| H5: MAS → IU | 0.004 (0.218) |

| H6: PDI → IU | -0.026 (1.256) |

| H7: UAI → IU | -0.007 (0.380) |

| H8: PEOU → IU | 0.351 (15.374)** |

| H9: PU → IU | 0.495 (19.798)** |

| H10: PEOU → PU | 0.331 (10.579)** |

| Model R2 | 0.741 |

| *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 | |

As for individual hypotheses, H1 proposed a positive relationship between perceived substitution and the intent to use electronic newspaper, and was supported at the 0.01 significance level. H2 posited that perceived substitution is positively related to perceived usefulness, and was also supported.

Hypotheses H3 through H7 related the cultural constructs to the intent to use electronic newspaper. With the exception of H4, which proposed a negative effect of long-term orientation on the intent to use and was supported at the 0.05 significance level, none of the cultural constructs were supported by the analysis.

H8 to H10 were based on previous studies (Gefen et al., 2003; Gefen and Straub, 2000; Yoon, 2009) and all three were supported. H8 and H9 posited a positive relationship between perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness respectively to the intent to use. Both were supported at the 0.01 significance level. Finally, H10 related perceived ease of use to perceived usefulness; it too was supported at 0.01significance level.

Discussion

Perceived substitution

The results of this study suggest a causal relation between perceived substitution and the intent to use electronic newspaper. While studies of the effect of substitution factors on adoption have been performed before (Briggs et al., 2001; Lin, 2001), to the best of our knowledge this is the first case where perceived substitution has been compared with cultural factors in their influence on technology adoption. Thus this study may help bring new light to what drives consumer adoption.

The results suggest that while the intent to use electronic newspaper is driven by its perceived usefulness, this usefulness is in turn influenced by the significant perceived substitution effect. In other words, whether a new technology is seen as a good substitute for the existing one is a precursor to how useful it is perceived to be. This suggests that perceived usefulness may not be the ultimate determinant of the intent to use technology and the comparative benefits of the new technology compared to the existing one may be precursors to the perceived usefulness of the new technology.

Additionally, perceived substitution may be an important, and measurable, precursor to technology adoption. Perceived substitution was found to have a direct positive influence on the intent to use. This may indicate that the more electronic newspaper can be made to have the characteristics of a printed newspaper, with added functionality such as online access and variable font size, the greater the likelihood of its adoption. This study was more interested in juxtaposing extant explanations of adoption, however future studies may investigate the specific relative weights users give to common and diverging characteristics of existing and substitutive technologies in finer detail. Perceived substituting characteristics of a new technology thus describe expectations of this new technology compared to the existing one, which may lead to its adoption (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010). While as noted by Briggs et al. (2001), these expectations and perceptions of the substitution effect may not always be rational, we were able to isolate them and measure their influence on the intent to use.

This is an important theoretical contribution, especially when compared with the lack of influence of cultural factors. Previous studies in the media domain have found substitution to moderately influence adoption while being complemented by other factors (Lin, 2001). By contrast, our results suggest that the intent to use electronic newspapers is culture-invariant and is driven primarily by the desire to gain access to technology that has greater benefits than the existing one, such as extended functionality, or when the old technology no longer satisfies user needs (Schmidt and Druehl, 2005).

Since this study was conducted prior to substantive consumer adoption of electronic papers, it captured customer assessments and expectations of this technology. This is both a strength and a potential point for improvement. The benefit of this approach is that even though the technology has not been offered in the market yet, it is possible to capture customer attitudes towards adopting this technology. Such an approach is theoretically in line with previous studies which showed that such subjective assessments are an important part of the decision to substitute an existing technology (Briggs et al., 2001). On the other hand, we investigate a relatively complex technology (the electronic newspaper artefact) which indeed most new technologies are likely to be (Tsai et al., 2010); actual experience of respondents with electronic newspapers was limited at the time the survey was conducted, and this may have affected the results. It also did not allow the research to probe deeper into specific design and usability differences between print and electronic paper.

Culture and technology adoption

Another aspect of this study is how the effect of individual-level culture interplays with the intent to use. Only one cultural variable, long-term orientation, was found to be statistically significant (at the 0.05 significance level).

Since the measures of culture were built on previously successful studies (Srite and Karahanna, 2006; Yoon, 2009), the lack of influence of individual cultural characteristics on adoption is an interesting finding. Although some of the cultural characteristics have been found to not have an influence on adoption, such as masculinity at the national level (Erumban and de Jong, 2006), this absence of support was typically compensated by the significant influences of other cultural characteristics. This lack of influence may be caused by an explanation offered by Srite and Karahanna (2006), who suggested that cultural values may play different roles depending on the stages of the acceptance process, especially at the initial acceptance or adoption decision. The results of this study support this argument. At initial stages of the adoption process substitution factors may play a far more significant role than cultural variables. Culture was measured at the individual level, as adoption of electronic newspapers is viewed as an individual decision. National cultural characteristics typically do not describe well individual variations in culture (Lee et al., 2007) and thus may not be a good explanatory variable in the adoption model. This is a possible avenue for future research.

Conclusion

This study conducted an analysis of the influence of perceived substitution as well as cultural factors on the intent to use electronic newspapers. It used data from three Scandinavian countries: Denmark, Norway and Sweden. All three have very high levels of newspaper readership and similarly structured newspaper markets (Hallin and Mancini, 2004), making them an excellent setting for an investigation of the change of a new technological artefact for delivering newspaper content such as electronic newspapers.

The results suggest that the influence of perceived substitution on both perceived usefulness and the intent to use electronic newspapers is significant, while the effect of cultural dimensions on the intent to use is not. This indicates that characteristics of electronic newspaper may be an important driver of adoption while cultural characteristics of potential users may not be. This is an important finding given two countervailing trends. On one hand, print newspaper circulation has been falling in many countries (typically in the developed world) but rising in some (Kilman, 2012; The Economist, 2013). On the other hand, the adoption of digital and mobile technologies, which are often used to access newspaper content, is increasing in most countries, with many having reached saturation levels (International Telecommunications Union, 2014). This study draws attention to the characteristics of a technology artefact that may facilitate this transition from print to electronic newspapers, which may be more significant than cultural characteristics of the potential consumer. Further studies focusing on other technologies or geographies may shed more light on the extent to which common and diverging characteristics of existing and substitutive technologies are valued by consumers.

From the practical perspective, the significant effect of perceived substitution suggests that the focus for managers should be to explain to consumers how the electronic newspaper will function as a direct substitute for the printed newspaper and how it is useful in their everyday life. This might be achieved by explaining how the technological advantages inherent in the product improve a product many Scandinavians have a very personal relationship with (Ihlström and Henfridsson, 2005). It should be considered an additional bonus that consumers generally seem to be technologically confident enough to operate the electronic newspaper once acquired and do not perceive a new electronic device in their daily life to offer any particular problems.

At the same time, we did not focus on the extent to which print newspapers may be substituted by electronic ones. While this was not our intent, there is currently a lively debate on that subject, with some studies finding evidence for an overall increase in media consumption, and thus electronic newspapers, among others, playing a complementary role to other media channels (Newell et al., 2008; Nguyen and Western, 2006); while others highlight that online newspaper readership significantly reduced consumption of print versions (De Waal and Schoenbach, 2010). The perceived substitution construct and our theoretical model in principle do not rule out significant displacement of print newspapers by electronic ones, with print newspapers being left in a niche that caters to specific and narrow customer segments. Such incomplete substitution has been observed with other technologies (Newell et al., 2008), such as vinyl records.

This study necessarily has limitations. It relied only on a quantitative methodology, which can be complemented by qualitative methods to probe deeper into the relationship between substitution, culture and the intent to use electronic newspapers. Participant observation and focus groups could also be used to investigate design differences between electronic and print newspapers in detail, and thus the relative importance of design factors in substitution.

Future research could use the results of this study in several ways. First, the relationship between perceived substitution and actual use should be established, since the link between the intent to use and actual use can be tenuous. Second, this study can be replicated in other industries and with other technological artefacts to determine whether the results here apply primarily to the media industry or similar effects can be seen in other industries too.

About the authors

Nicolai Pogrebnyakov is an Associate Professor at Copenhagen Business School.

His research and teaching focus on the use of technology to facilitate innovative business models, innovation in interfirm networks, and technology-enabled business models. He holds a PhD in Information Sciences and Technology from the Pennsylvania State University. He can be contacted at nip.int@cbs.dk.

Mikael Buchmann works with provision of new technologies for the media and entertainment industry. His research has focused on issues relating to the adoption of new media and consumer preferences for information dissemination technologies. Mikael received his MS in international business from Copenhagen Business School.