Personal and political elements of the use of social networking sites

Jenny Bronstein and Noa Aharony

Department of Information Science, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan, Israel

Introduction

Social networking sites have become an important part of the lives of millions of Internet users because they allow people without any particular technical knowledge to create an online profile and to communicate and share information with others. Although social networking sites play a predominantly social role by helping users create and maintain a network of social connections (boyd and Ellison, 2007), scholars have found that these sites have become an information source that can rapidly disseminate innovative information and values by providing an opportunity for ordinary citizens to create their own political content, distribute it online, and comment on the content create by others (Gibson, 2001; Hanson, et al., 2010). Prior studies have found that social networking sites have different political uses and purposes such as allowing a direct interaction between politicians and potential voters (Carr and Shelter, 2008; Cohen, 2008), facilitating dialog (Fernandes, et al., 2010), and changing the political media environment that resulted in increased feelings of citizen efficacy in the political process (Kirk and Schill, 2011). The creation and exchange of user-generated content has been identified as key to events as diverse as the rise of social protests in Pakistan, Britain, Chile, and France and the outbreak of revolution in the Arab world (Jones, 2011; Shaheen, 2008). Social networking sites have been used as political platforms not only during periods of social and political upheavals, but also as propaganda tools during political campaigns and as sources for political information during elections (Aharony, 2012; Bronstein, 2013; Keat, 2012; Lappas, Kleftodimos, and Yannas, 2010).

Social networking sites were found to be more user-centered than traditional media thus allowing new types of political interactions that were not available in previous presidential campaigns (Hanson et al., 2010). In a survey conducted during the 2012 US presidential election, Rainie (2012) found that social networking sites acted as a platform for political activism, when 39% of all American adults used these sites for political purposes; 35% of social networking sites' users used these platforms to encourage people to vote, 33% reposted content related to political issues and 31% used social sites to encourage other people to take action on a political or social issue. Because of the new significance that social networking sites have on the creation and dissemination of information in general and of political discourse in particular the current study examines both personal and political aspects of SNS use. That is, it explores the relationship between social networking sites use and personal motivations and social network intensity and three elements of political behavior: political motivations, political self-efficacy and political engagement.

Literature review

This study investigates both personal and political elements of social networking sites use. The first part of this section presents the theoretical framework for the study and prior research related to personal motivations; this is followed by the research survey on political behaviours and their relationship to social networking sites use.

Motivations for social networking sites use

The present study examined the personal and political motivations that drive the use of social networking sites based on the uses and gratification theoretical framework. The concept of motivation has been described as 'a process governing choice made by persons among alternative forms of voluntary activity (Vroom, 1964: 6). The uses and gratification framework examines the motivations people have to use a certain mass medium and assumes that people use different media purposively, selectively and actively to satisfy their needs (Katz, Blumler, and Gurevitch, 1974; Klapper, 1963). This theory has served as theoretical framework in a large number of studies that investigated the use of and interactions with different types of media (Bronstein, 2012; Funk and Buchman, 1996; Mendelsohn, 1964; Newhagen and Rafaeli, 1996). The main objectives of the this type of inquiry are to explain how people use media to gratify their needs, to understand motives for media behavior, and to identify functions or consequences that follow from needs, motives and behavior (Katz, Blumer, and Gurevitch, 1974).

There is a substantial amount of research dealing with the personal motivations for using social networking sites. In an earlier study Joinson (2008) identified such motives as social connection, shared identities, photographs, content, social investigation, social network surfing, and status updates. Other studies have found that users are motivated to use social networking sites for information seeking purposes, identity creation and impression management (Dunne, Lawlor and Rowley, 2010; Zhang, Tang and Leung's, 2011); for sharing information (Pempek, Yarmolayeva and Calvert, 2009), to gain immediate access, coordination and affection (Xu et al., 2012), or to gratify emotional and cognitive needs (Wang, Tchernev and Solloway, 2012). Studies of motivations for using social networking sites have found that these sites primarily serve social interaction needs (Postelnicu and Cozma, 2008; Royal, 2008; Sweetser and Weaver-Lariscy, 2008) such as getting recognition and support from others (Zhang, et al. 2011), maintaining and extending social connections, and developing social enhancement (Cheung, Chiu and Lee, 2011; Pempek et al., 2009; Xu, et al., 2012).

Socially related motivations have been found to be central to the use of social networking sites because these sites provide users with the opportunity to create and maintain online social connections or friends with their network of family members, coworkers, and other acquaintances an activity known as friending (Ellison et al, 2006). In general, friends are defined as 'a subset of peers who engage in mutual companionship, support and intimacy' (Kim and Lee, 2011, 360). Amichai-Hamburger, Kingsbury and Schneider (2012) explained that social networking sites foster socialization because the asynchronic nature of electronic communication eliminates barriers to communication such as differing time zones, which are a by-product of geographic distance. Ellison et al., (2006) stated that there is a positive relationship between certain kinds of social networking sites use and the maintenance and creation of social connections or numbers of friends. They proposed a measure called Facebook intensity which includes two self-reported assessments of social network behavior designed to measure the extent to which the participant was actively engaged in social network activities: the number of Facebook friends and the amount of time spent on Facebook on a typical day. The present study investigated the level of the participants' engagement with social networking sites through the social network intensity measure and its relation to demographic variables such as age and sex.

Elements of political behavior

This study investigated three elements of political behaviour and their interaction with social networking sites use. The first element of political behavior investigated is political engagement that is defined as the perceived relevance of an issue at a given moment or the degree of interest in social situations such as election outcome (Austin and Pinkleton, 1999; Pinkleton and Austin, 2004). A number of studies in recent years have investigated political engagement through social networking sites. Kushin and Yamamoto (2010) posited that the link between social networking sites use and political behaviors is influenced by what motivates people to search out information. Conroy, Feezell, & Guerrero, (2012) asserted that social networking sites have created new ways to bridge the gap between users through groundbreaking interactive technologies. Tsang (2012) further explained that social networking sites could foster political engagement because they raise awareness about collective problems, reinforce online political discussion and highlight opportunities for civic or political involvement. Contrarily, Zhang et al. (2011) found that social networking sites use was positively related to civic participation but not to political participation. On the same line, Postelnicu and Cozma (2008) stated that relying on social networking sites for social utility led to less online political activity.

The second element of political behavior examined in the study is the concept of political self-efficacy. The concept of political self-efficacy was conceptualized by Campbell, Gurin and Miller (1954, 187) as 'the feeling that individual political action does have, or can have an impact upon the political process, namely, that is worthwhile to perform one's civic duties'. This characteristic has been shown to be highly predictive of political participation (Scheufele and Nisbet, 2002). Political self-efficacy is linked to Bandura's (1986) general notion of self-efficacy that states that the relationship between knowledge and action is based on how people judge their capabilities and how their self-percepts of efficacy affect their motivation, behavior, thinking and feelings.

The third element of political behaviour examined in the study is the concept of political motivations. Losier et al. (2001) posited that political motivations are the reasons why people follow politics and they explained people's participation in the democratic process. Hanson et al. (2010) asserted that the uses and gratification theory is particularly suited to investigate the political motivations behind the use of SNS because this type of media facilitates the distribution of information amongst users. Hence, the ability of users to control political media choices makes it appropriate to apply a user-centered media perspective such as the uses and gratifications framework to assess the effects of media use. The unique ways in which individuals can participate politically via social networking sites has encouraged scholars to begin to probe reasons why they do so. Macafee (2013) observed that participants engaged socially with other Facebook users by posting comments and links and presented themselves to other users by liking' political figures on the website. Vitak et al., (2011) claimed that information is one of the four main motivations for political use of social networking sites alongside with social engagement, entertainment, and self-presentation. They also stated that political motivations for social networking sites use can result in the development of civic skills and in an increased political engagement. Contrarily, Andersen and Medaglia (2009) found there is no relationship between social networking sites use and political behavior because the information encountered on a candidate's Facebook page had no influence in the user's decision making process since users already knew the candidates through the traditional channels of party organizations.

Understanding the relationship between social networking sites use and political behavior is important since prior studies have found contrasting findings regarding this relationship. Conroy et al., (2012) claimed that social networking sites foster political participation by creating new ways to bridge the gap between users through groundbreaking interactive technologies. Curtin and Meijer (2006) posited that since social networking sites have become an important communication platform for social and political movements they are able to mobilizing people in a time of crisis. Contrarily, Hanson et al., (2010) and Kohut (2008) found a lack of correlation between SNS use and political behaviors and explained that users do not actively seek political information but rather encountered it by chance; therefore the unintended receiving of political content may not serve to activate user's political behaviors related to social networking sites use. Park et al. (2009) provided a different explanation by claiming that users participate in Facebook groups mainly for entertainment needs which do not encourage their participation in political events. The current study aims to further the existing knowledge about the relationship between the three political behaviours mentioned above and social networking sites use.

Value of the study

Social networking sites have become a predominant and unique platform that allows content to be created and information and opinion to be directly transferred from user to user. This is one of the reasons why social networking sites are beginning to play a significant role in social and political processes around the world. Hence, the current study examined the possible relationship between social networking sites use and political motivations and behaviours. It also furthers the existing knowledge about the relationship between social networking sites use and personal motivations and social network intensity.

Methodology

Hypotheses

- H(1) The higher respondents' SNS use is, the greater their political engagement is.

- H(2) The higher respondents' SNS use is, the greater their political self-efficacy is.

- H(3) The higher the respondents' political motivations are, the higher their political engagement.

- H(4) The more politically self-efficient respondents are; the higher their political engagement

- H(5) The higher respondents' SNS use is, the greater their political motivations for SNS use are.

- H(6) The higher respondents' SNS use is, the greater their personal motivations for SNS use are.

- H(7) The higher respondents' SNS use is, the more friends they have.

- H(8) The higher the respondents' political motivations are, the fewer friends they have.

- H(9) The higher the respondents' personal motivations are, the more friends they have.

Data collection

The study was conducted over two months (October-November 2012) using a survey. The population of the study consisted of 155 Information Science students enrolled in bachelor and master's degrees at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. There are approximately 800 enrolled nationwide. Researchers received permission to enter different courses at Bar-Ilan University and delivered 180 questionnaires to the students. They explained the study's purpose to them and, 155 responded. Participants were mostly (62.7%) women, age 20 to 58 years old (M=age 28.1 SD=6.7), with a bachelor degree (60.8%).

Measures

Researchers used five questionnaires to gather data.

- Demographic questionnaire that had three statements ("Questionnaire A").

- Social network usage questionnaire that had three questions ("Questionnaire B").

- Motivations questionnaire that had thirty-six statements divided into two sections:

a. Motivations for personal use: twenty-five statements that investigated personal motivations for SNS use rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongest disagreement; 5= strongest agreement). This questionnaire has been validated previously (Lin, 2005; Bronstein, 2012) and its Cronbach's Alpha value was 0.93 ("Questionnaire C")

b. Motivations for political use: eleven statements that investigated political incentives for SNSuse rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongest disagreement; 5= strongest agreement). The Cronbach's Alpha value was 0.92. ("Questionnaire D") - Political self-efficacy questionnaire had four statements rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongest disagreement; 7= strongest agreement). That is, the higher the rating given by participants the stronger their self-efficacy is. This questionnaire has been validated previously (Hanson et al., 2010) and its Cronbach's value was 0.88. ("Questionnaire E")

- Political engagement questionnaire had four statements rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1=strongest disagreement; 7= strongest agreement). That is, the higher the rating given by participants the stronger their political engagement is. This questionnaire has been validated previously (Kushin & Yamamoto, 2010) and its Cronbach's Alpha value was 0.92. ("Questionnaire F")

Results

Pearson correlations were performed to examine the relationship between age, personal motivation, political self-efficacy, political motivation, social networking sites use and political engagement, and number of friends. The results of the statistical analysis are presented in Table 1.

| Measures | Age | Personal motivation |

Political self-efficacy |

Political motivation |

Social networking use |

Political engagement |

Friends |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | -0.33** | -0.07 | -0.09 | -0.26** | 0.02 | -0.41** | |

| Personal motivation | -0.09 | 0.50*** | 0.39*** | 0.08 | 0.37*** | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.23** | 0.10 | 0.39*** | 0.09 | |||

| Political motivation | 0.24** | 0.52*** | 0.07 | ||||

| SNSuse | 0.05 | 0.48*** | |||||

| Political engagement | -0.09 | ||||||

| Friends | |||||||

| **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 | |||||||

Table 1 shows that significant positive correlations were found between political engagement and political self-efficacy and political motivations. Therefore, we may conclude that the higher the political self-efficacy of participants is, and the greater their political motivations are, the higher their political engagement will be. Significant positive correlations were also found between friends and personal motivations and social networking site use. In other words, the higher participants' personal motivations are and the higher their social networking site use is, the more friends they have. A significant negative correlation was found between the number of friends and age, that is, the younger participants are the more friends they have. An additional significant negative correlation was found between personal motivations and age. Hence, the younger participants are, the higher is their personal motivations are. Significant positive correlations were also found between political motivations and political self-efficacy. In other words, the greater participants' political motivations are the higher their political self-efficacy is. Furthermore, significant positive correlations were found between social networking site use and personal and political motivations. Hence, the higher participants' personal and political motivations are, the greater their social networking site use will be. A significant negative correlation was found between social networking site use and age, thus, the older the participants, the less they use social networking site.

Researchers also conducted two hierarchical regressions using political engagement and number of friends and as two dependent variables. In the first regression in which political engagement was the dependent variable the predictors were entered as four steps. (1): participants' biographical variables such as: age and sex; (2) participants' personality characteristic: personal motivation; (3) variables that are associated with political aspects such as: political self-efficacy and political motivation; (4) participants' online time. This regression explained 41% of the variance of participants' political engagement. Table 2 presents the standardized and unstandardized coefficients of the hierarchical regressions of respondents' political engagement.

| Predictors | B | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Sex | -0.52 | -0.14 | ||

| 2. Age | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Sex | -0.50 | -0.14 | ||

| Personal Motivation | 0.20 | 0.09 | ||

| 3. Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.41** | 0.38** |

| Sex | -0.44 | -0.12 | ||

| Personal motivation | -0.51 | -0.22* | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.31 | 0.28** | ||

| Political motivation | 1.11 | 0.56** | ||

| 4. Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.41** | 0.00 |

| Sex | -0.43 | -0.12 | ||

| Personal motivation | -0.53 | -0.23* | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.31 | 0.28** | ||

| Political motivation | 1.11 | 0.56** | ||

| Time | 0.00 | 0.04 | ||

| *p<0.01; ** p<0.001 | ||||

The first, second and forth steps did not contribute to the explained variance of respondents' political engagement. As the third step, researchers added variables that are associated with political aspects such as: political self-efficacy and political motivation that contributed 38 % to the explained variance of respondents' political engagement. The beta coefficients of political self-efficacy and of political self-efficacy were positive; thus, the higher respondents' political self-efficacy is, and the greater their political motivations are, the higher their political engagement will be. The beta coefficient of personal motivation was negative, thus, the higher the personal motivations of respondents are, the less they are politically involved.

Regarding the second hierarchical regression in which number of friends was the dependent variable, predictors were entered as six steps. The first four are the same as appear in the first regression. The fifth step refers to participants' political engagement, and the sixth to interactions with political engagement and with motivations. This regression explained 35% of participants' variance of number of friends. Table 3 present the standardized and unstandardized coefficients of the hierarchical regression of respondents' number of friends.

| Predictors | B | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -0.17 | -0.40† | 0.16† | 0.16† |

| Sex | 0.23 | 0.03 | ||

| 2. Age | -.14 | -0.31† | 0.22† | 0.06* |

| Sex | 0.30 | 0.05 | ||

| Personal motivation | 1.01 | 0.25† | ||

| 3. Age | -0.13 | -0.29† | 0.24† | 0.02 |

| Sex | 0.24 | 0.04 | ||

| Personal motivation | 1.29 | 0.33† | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.13 | 0.06 | ||

| Political motivation | -0.51 | -0.15* | ||

| 4. Age | -0.13 | -0.29† | 0.28† | 0.04* |

| Sex | 0.35 | 0.05 | ||

| Personal motivation | 1.11 | 0.28** | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.17 | 0.09 | ||

| Political motivation | -0.51 | -0.15* | ||

| Time | 0.05 | 0.21† | ||

| 5. Age | -0.13 | -0.29† | 0.29† | 0.01 |

| Sex | 0.2 5 | 0.04 | ||

| Personal motivation | 0.99 | 0.25** | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.24 | 0.12 | ||

| Political motivation | -0.28 | -0.08* | ||

| Time | 0.05 | 0.21† | ||

| Political engagement | -0.20 | -0.12 | ||

| 6. Age | -0.14 | -0.32† | 0.36 † | 0.06† |

| Sex | 0.25 | 0.04 | ||

| Personal motivation | 0.7 9 | 0.20* | ||

| Political self-efficacy | 0.21 | 0.11 | ||

| Political motivation | -0.17 | -0.05 | ||

| Time | 0.05 | 0.21† | ||

| Political engagement | -0.15 | -0.09 | ||

| Time X Engagement | -0.46 | -0.17* | ||

| Sex X Personal motivation | -0.45 | -0.15* | ||

| Sex X Political motivation | 0.55 | 0.19* | ||

| *p<.05; **p<.01; † p<.001 | ||||

The first step introduced the biographical variables: age and sex that contributed 16% to the explained variance of respondents' number of friends. Of these two variables, only age contributed significantly and its beta coefficient was negative. In other words, the older respondents, the fewer friends they have.

The second step introduced respondents' personality characteristic: personal motivation that contributed 6% to the explained variance of respondents' number of friends. Thus, the higher their personal motivations, the more friends they have.

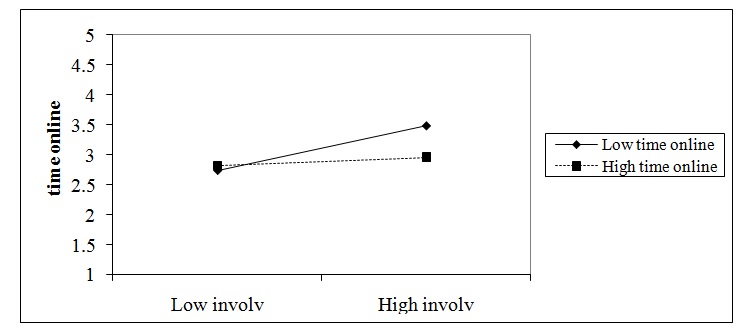

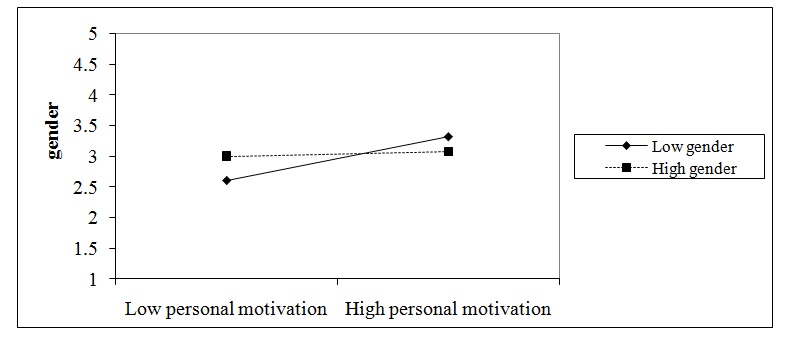

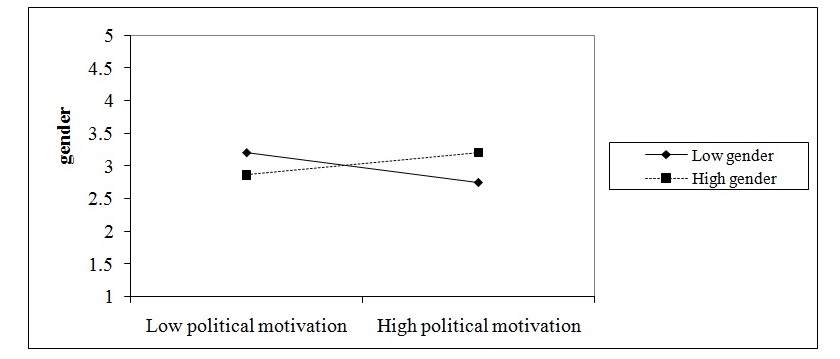

As the third step, researchers added variables that are associated with political aspects such as: political self-efficacy and political motivation that contributed 2 % to the explained variance of respondents' number of friends. Of these two variables, only the political motivation contributed significantly and its beta coefficient was negative. In other words the lower respondents' political motivations are, the more friends they have. The fourth step added respondents' online time that also contributed significantly by adding 4 % to the explained variance of respondents' number of friends. The beta coefficient of online time was positive, hence, the more time respondents spend online, the more friends they have. As the fifth step, researchers added respondents' political engagement that that did not contribute significantly to the explained variance of respondents' number of friends. In the sixth step, researchers added the interactions between time online X political engagement, sex X personal motivation, and sex X political motivation. These interactions added 6 % to the explained variance of respondents' number of friends. The interaction of time online X political engagement is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows a correlation between online time and political engagement and number of friends, among respondents who are low in online time. This correlation is higher among respondents who are low in online time, β=0.4, p >0.05. than among those who are high in online time, β=-0.24, p <0.05. It seems that especially among participants who spend limited amounts of time online, the higher their political engagement, the higher their number of friends. The interaction of sex X personal motivation is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows a correlation between sex and personal motivation and number of friends, among males. This correlation is higher among males who are high in personal motivation, β=0.45, p <0.01, than among males who are low in personal motivation, β=0.18, p >0.05. It seems that especially among males who are high in personal motivations, the higher their personal motivations are, the higher their number of friends will be.

Figure 3 shows a correlation between sex and political motivation and number of friends, among males and females. Among males, the higher their political motivations are, the fewer friends they have, β=-0.34, p <0.05, and among women, the higher their political motivations are, the more friends they have β=-0.01, p >0.05.

Discussion

The current study examined political aspects of social networking sites use such as political motivations, political engagement and political self-efficacy (H1, H2, H3 H4, H5) and personal elements of social networking sites use such as the number of friends and personal motivations (H6, H7, H8, H9). Researchers predicted that the higher the participants' use of social networking sites is the higher their political engagement (H1) and their political self-efficacy (H2) will be. H1 and H2 were not supported by the findings. No significant correlations were found between the use of social networking sites and the political self-efficacy and the political engagement of participants. These findings parallel results from other studies that question the political utility of social networking sites use (Ancu and Cosma, 2009; Esposito, 2012; Hanson et al., 2010; Kushin and Yamamoto, 2010; Zhang, et al., 2011). This lack of correlation is explained by claiming that users of social networking sites encountered political information by chance when using social networking sites for entertainment needs (Hanson, , 2010; Park et al. 2009). Although findings show no significant correlations between social networking sites use and political behaviors, a significant correlation was found between respondents' political motivations and their political engagement (H3). This result echoes prior studies that found that users who would be most likely to use social networking sites to obtain political information would be individuals who already exhibit greater levels of political interest and knowledge (Delli and Keeter, 2003; Park, , 2009; Tsang, 2012; Vesnic-Alujevic, 2012). Relatedly, H4 predicted that the higher the participants' political self-efficacy is the higher their political engagement will be, that is, users who feel that their political actions can have an impact upon the political process, will become more politically engaged. This hypothesis was supported by the findings in this study and in prior studies (Scheufele and Nisbet, 2002). In sum, the analysis of the data shows that the political engagement of participants was influenced by their political motivations and their political self-efficacy. Based on these findings we would like to suggest that participants who were politically engaged were motivated to use social networking sites to get acquainted or to connect with a candidate, a politician or a political party (Esposito, 2012; Sweetser and Weaver-Lariscy, 2008) and felt that their political actions could have an impact on the political process in general or maybe on the politician they wanted to connect with.

The interpersonal aspect of social networking sites makes the uses and gratification approach particularly suitable as a research framework because it focuses the fulfillment of psychological and social needs and the motivations for the use of a particular media (Chen, 2011). The current study examined the impact that social networking sites use has on political (H5) and personal (H6) motivations for using these sites. Research has suggested that the link between social networking sites use and political attitudes and behaviors is influenced by what motivates people to search out information (Kushin and Yamamoto, 2010). Researchers hypothesized that the higher the use of social networking sites is the higher the political motivations of participants will be (H5) because these sites allow users to experience politics at a more personal level therefore fulfilling a need for political user-generated content that might not be available through traditional news sources (Kushin and Yamamoto, 2010). This hypothesis was supported by the findings. The analysis of the data shows a significant correlation between SNS use and political motivations. This result supports data on a recent survey by the Pew Internet & American Life Project that examined the use of social networking sites during the 2012 US presidential election and found that social networking sites played a modest role in influencing most users' political views (Rainie and Smith, 2012). Moreover, the analysis of the data shows that political motivations influence the political self-efficacy of participants, that is, users who feel that their actions on the social network could have an impact on the political process will be more motivated to use these social networking sites for political reasons. The analysis of the data also found a significant correlation between social networking sites use and personal motivations (H6).

The number of online social connections or friends is another personal element of social networking sites use investigated in the study. H7 examined the social network intensity of participants, that is, the relation between personal elements of social networking sites use and the number of friends that participants have on the network. H7 was supported by the findings that reported a high social network intensity (Ellison et al., 2006) reflected in a significant correlation between SNS use and the maintenance and creation of online social connections. As Krasnova, et al. (2010, p. 121) noted: 'A small post on the wall is a simple way to remind others about oneself, helping to keep relationships alive.' The analysis of the data revealed a significant negative correlation between the number of friends, age and social networking sites use, that is, younger participants had a higher social network intensity. These results support previous studies that showed that younger users feel more comfortable using social networking sites (Nosko, Wood and Molema, 2010) and have more friends (Aharony, 2013; Hargittai, 2007).

The present study also investigated the impact that political (H8) and personal (H9) motivations might have on the number of friends. H8 predicted that higher political motivations for social networking sites use will result in fewer friends. This prediction was supported by the findings. This result supports prior studies that stated that people use social networking sites to look for information on a politician or party they know and maybe to form an emotional connection with them (Esposito, 2012; Park, et al., 2009; Sweetser and Weaver-Lariscy, 2008; Tsang, 2012). That is, politically motivated participants accessed social networking sites for purposes related to political information and engagement and not for socialization purposes. Similarly, Bogers and Wernersen (2014) in a study about motivations to use the social news site Reddit also suggested that one of the strongest motivations for social networking sites use was the reception of news related information and not so much the socialization aspects of the site. However, we also found that according to the first interaction, participants who spend limited time on social networking sites have higher political motivations and a higher number of friends.

An interesting difference between male and female participants regarding political motivations and number of friends was revealed in the third interaction. Findings show that male participants with higher political motivations had the fewer friends, while female participants who reported having higher political motivations, had a larger number of friends. This finding echoes Postelnicu and Cozma (2008) assertion that the relationship between the use of media sources and political attitudes is not always a direct one since it can be affected by demographic or personality factors. Muscanell and Guadagno (2012) further explained these sex differences in the number of friends by claiming that women are more likely to use the Internet to ease social interaction and to maintain existing relationships while men are more likely to spend their time online engaging in more task-focused activities.

H9 that predicted that high personal motivations for social networking sites use will result in a larger numbers of friends was also supported by the findings. This result reinforces the existing notion in the literature that users are primarily motivated to use social networking sites as an effective channel for relationship building, professional networking and recognition (Royal, 2008; Sweetser and Weaver-Lariscy, 2008; Zhang et al., 2011). Contrarily to findings regarding political motivations, the results from the second interaction show that male participants with higher personal motivations have more friends. This finding contradicts prior studies that found that women tend to have more online social connections than men (Bonds-Raacke and Raacke, 2010; Burke, Marlow and Lento, 2010).

Conclusion and limitations

Although social networking sites have the potential to become communication platforms that foster political activism, findings from this study show that they have yet to become significant enough in the users' information environment to have an impact on political behaviors. However, two interesting findings related to political motivations help to shed some light on political behavior on social networking sites. The influence that political motivations have on the participants' political self-efficacy and political engagement as well as the correlation that political motivations have with the number of online social connections could explain what motivates people to use social networking sites for political purposes. Namely, based on Esposito's (2012) and Sweetser and Weaver-Lariscy's (2008) studies, these results could suggest that users access social network sites to seek information about politicians or political parties possibly to create a connection or to identify with them. In sum, findings from the study portray social networking sites as platforms that allow users to access unique political user-generated content and foster a more personal political experience. In addition, this study extends the existing literature on personal elements of social networking sites use and shows that as a result of their availability and ease of use social networking sites have become a socially motivated platform that fosters unique opportunities for users to create and develop online social connections. The study highlights the demographic differences between different age and sex groups of users regarding the two personal elements of social networking sites use, social network intensity, and personal motivations.

Further research is needed to understand the role and significance of SNS use in the development of political behaviors online especially during an election period or a period of high political activity. The current study has a number of limitations. First, the sample is of convenience therefore is not representative of all Israeli social networking sites users. However, studies examining interactions with social networking sites frequently use convenience samples, including university students (Lee and Ma, 2012; Smock et al., 2011). Second, the items comprising political motivations for social networking sites use and political engagement are not exhaustive. Finally, the data for the study was collected before the general elections of 2013 were called In Israel, a fact that could have influenced the participants' responses.