Mobile devices and information patterns amongst tourists

Stan Karanasios

AIMTech Research Group, Leeds University Business School, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK

Carmine Sellitto and Stephen Burgess

College of Business, Victoria University, PO Box 14428, Melbourne, Australia, 8001

Introduction

Over the last decade there have been significant changes in patterns of information search and information consumption (Bohn and Short 2012, Nicholas 2013). Specific studies and reports have highlighted the accelerated information flows via different mediums, such as mobile devices (Nicholas 2013). In this paper we explore how mobile devices are used in situ for the travel purposes as there is limited literature which explores how they alter or complement information behaviour activities. For the purposes of this article, mobiles devices refers to devices that can be carried by a tourist 'on their person', are used as part on daily activities and have the capability of accessing the Internet. Such devices include smart phones, tablet devices and to a lesser extent the laptop computer. Whilst these devices each offer different experiences for the user, the nature of tourism as an inherently nomadic activity aligns well with the utility provided by all of these devices in that are relatively small (compared to the traditional personal computer), portable (in varying degrees) and offer a high degree of flexibility for users.

Mobile devices used by people when vacationing impart benefits associated with timeliness, ubiquity and convenience- allowing individuals to engage in information exchanges, whilst actually travelling (Burgess 2012). Part of this mobile exchange impacts how people plan a trip. Planning activities have traditionally been a core part of a pre-departure phase (Fesenmaier and Jeng 2000)- yet the value of mobile devices is arguably one of providing opportunities in accessing tourism information services in situ. Hence, this paper explores how mobile devices might be influence patterns of information behavior in tourism activities- subsequently aligning common mobile information services to the various tourist planning stages.

Literature Review

The tourist planning process

The planning process has been previously documented as an important multi-staged process that tourists engage in when organizing a trip. Wang (2012) note that tourists will plan aspects of their trip based on their requirements that fall into an anticipatory phase, experiential phase, and reflective phase, with distinct decisions about the trip occurring across each of the stages. Cox (2009) used the pre-trip, during-trip and post-trip stages to define the planning process. The pre-trip planning stage identified travel requirements and the subsequent use of information to plan/purchase appropriate activities/products. The during-trip stage was the actual taking of the trip. The post-trip stage included an evaluative element allowing the tourist to reflect on their vacation after returning home. Choi (2009) examined decision-making amongst a cohort of Chinese tourists that grouped their activities in the sequence of before purchase, at time of purchase, after purchase and at destination. Given the expanding prevalence of mobile device use by people and the application of such devices in the tourism domain, it becomes desirable to not only identify the beneficial aspects of using such devices, but also align these benefits with the various stages of planning. Arguably, the associated mobile device benefits that are timely, location-specific, and have the propensity to alter the behavior of tourists across the planning process.

An alignment of mobile information services and the planning proces

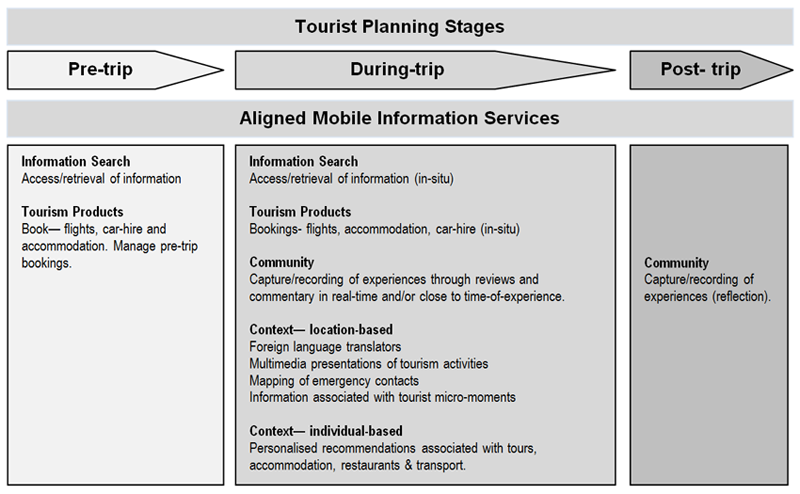

We contended that mobile information services can be mapped to the three stages of traveler planning. Some services might be applicable to a range of generic tourism activities whilst other services are more specific, being associated with activities such as communication exchanges during tour participation, booking of tourism-related products such as accommodation before or after commencing a trip, or even identifying an eatery at a destination. Information search benefits, access to tourism products and the ability to capture and record experiences (deemed community) augment the during-trip stage due to the influence of the Internet. Mobile devices tend to provide contextual information services commensurate with the location of the tourist and are typically associated with the during-trip stage. Figure 1 is a summary of the proposed alignment of mobile information services to pre-during and post-trip planning stages.

Mobile device services mapped to the pre-trip stage

In the pre-trip stages, services accessed on mobile devices provided the tourist the opportunity to undertake the traditional information search activities, as well as being able to purchase and/or manage tourism products. The information search activities allowed a person to be informed about activities such as destination events and the weather (Economou 2008), general tourism-related booking information (Hill 2010, Wang 2012) as well as information that could be tied back to personal circumstances. Potentially mobile devices also enable the tourist to focus on tourism products reflected in the purchasing of flights, accommodation or car hire (Buhalis and Law 2008) (Buhalis and Law 2008) and the management of the travel itinerary (Hill 2010).

Mobile device services mapped to the during-trip stage

The services potentially aligned with stage can be viewed under the rubric of information search activities, tourism products, community and benefits that can be derived reflect the context of the tourist experience. Such benefits tend to be similar to those noted in the pre-trip stage. However, community affiliated benefits reflected the ability of the mobile device to capture in real-time the personal and intuitive experiences of a person allowing them to share this information with other tourists- an activity that occurred whilst they were still on vacation or even physical on route between destinations (Goossen 2010, Kenteris 2011). Context services would be reliant on geographical location and recommender systems reflecting proximity to points of interest such as eateries, theme parks, tours and so forth.

Mobile device services mapped to the post-trip stage

In the post-trip stage of the planning process, mobile devices services will arguably reflect community information services- having a close affiliation with the community grouped activities noted for the during-trip stage. Community associated services might be based on the recording of tourism experiences during their trip via the mobile device (Kenteris 2011). The mobile-device activities associated with the post-trip stage which would focus on the evaluation of the tourist activities after a vacation appears to be limited (Goossen 2010. 2011). Arguably, if users have the opportunity to post real-time comments whilst on vacation they will, with any later post-trip sharing of experiences being one of recall or querying from others.

Conclusion

The paper contends that during travel planning a number of cross-over of information services are noted between the stages. Information search and tourism products activities have a crossover between pre-trip and during-trip stages. Services noted with community occurred both in the during-trip and post-trip stages. Some information services are applicable to a range of tourism activities whilst other services are more specific, being associated with activities such as communication exchanges during tour participation, booking of tourism-related products such as accommodation before or after commencing a trip, or the typical locating of an eatery at a destination. Traditionally there have been distinct stages associated with the planning process, each with well-defined activities. Arguably, searching for information and the subsequent purchasing of a tourism-related product might have been exclusively experienced as a pre-trip function. Clearly, internet-enabled mobile devices have allowed aspects of pre-and- post-trip services and activities to be undertaken outside of these traditional planning stages whilst people are actually on vacation (during-trip).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees for their valuable comments and constructive suggestions.

About the authors

Stan Karanasios is a Lecturer at Leeds University Business School. His research interests include information and communication technology development, activity theory and the use mobile information systems. His articles have appeared in MIS Quarterly, Information Systems Journal and European Journal of Information Systems. Stan can be contacted at sk@lubs.leeds.ac.uk.

Carmine Sellitto is a senior lecturer at Victoria University in the information iystems discipline. He is also affiliated as a research associate with the Centre for Applied Informatics. Dr Sellitto has published widely and some of his 100 peer-reviewed publications have been on topics on management, social media and tourism technology. Carmine can be contacted at carmine.sellitto@vu.edu.au.

Stephen Burgess is an Associate professor at Victoria University in the information systems discipline. Stephen has research interests that include the use of information technology by sporting bodies, user-generated content in tourism, mobile tourism devices and small business adoption of information and communication technologies. Stephen can be contacted at stephen.burgess@vu.edu.au.